When Conscience Calls for Treatment: The Challenge of Reproductive Care in Religious Hospitals

On January 18, 2018, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced the creation of a Conscience and Religious Freedom Division within its Office of Civil Rights. The purpose of the new division is to better enforce 25 existing federal statutes that allow health care workers to refuse to provide care that they believe conflicts with their religious beliefs or moral convictions. HHS cited tubal-ligation sterilization and abortion among examples of services that some health care providers may find objectionable [1]. Notably, these protections apply to corporations and institutions as well as individuals, meaning that a health care employer with a religious objection to certain reproductive services can legally prohibit employees from providing those services, regardless of employees’ personal beliefs. For health professionals who do not share their employer’s religious objection and believe they have a duty to provide care, this presents an ethical quandary.

Unfortunately, the new HHS office does not grant equivalent deference to individuals whose religion or moral code provides a “conscience motivation” to ensure that essential and compassionate care is provided. Nor does it honor the deeply held beliefs of patients who have a conscience motivation to undergo a certain procedure (e.g., sterilization or abortion) or to make a medical choice (e.g., contraception). Against the backdrop of an expanding number of institutions with religious restrictions, this oversight may exacerbate an imbalance of power among institutions, employees, and patients and hinder the delivery of essential reproductive health services.

The Unique Position of Religious Hospitals

Religious hospitals operate one in five hospital beds in the United States [2]. As with most hospitals, care from religious institutions is funded through public and private dollars. But these organizations are allowed to restrict certain health care services despite the public funding. In many cases, they are allowed to do so due, in part, to their founding as charitable institutions – even though, at present, religious hospitals do not provide more charity or Medicaid care than other nonprofit hospitals [2,3].

While religious hospitals can be of many faiths, 70 percent are Catholic affiliated – a number that has grown significantly in the past 15 years [2]. Catholic institutions are required to follow the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services (ERDs), written by the US Conference of Catholic Bishops [4]. The ERDs prohibit clinicians from providing contraception, male and female sterilization, abortion for any reason, most fertility treatment, and, in some cases, treatment during miscarriage, among other things. And while more varied in their permitted practices, non-Catholic religious hospital policies also often include restrictions. These tend to center on which abortions, if any, can be provided. Some Baptist hospitals, for example, allow abortions for fatal fetal anomalies, but not for other indications [5].

Despite these significant restrictions on services, from a patient’s point of view, religious hospitals are often indistinguishable from secular hospitals. Religious hospitals may not have names that convey their affiliation; nor do they always disclose religiously motivated care limitations to patients. Therefore, patients may not be aware that they have entered a facility that does not provide all forms of care.

Transparency, Information Delivery, and Referral

Religious hospitals employ and serve diverse individuals. The health professionals employed by them often want to provide the care their employers prohibit [6], and patients can find themselves surprised and hampered by institutional doctrinal limits on care they want and need [7]. Nonetheless, in communities where the only hospital is religious, or where there is a high level of religious health care saturation, there may be no other options for health care employment or services [2]. As publicly funded entities that control a significant portion of the health care market and resources, religious hospitals, we believe, have a duty to offer comprehensive care. Failing that, we believe they have a duty to communicate relevant limitations clearly in advance.

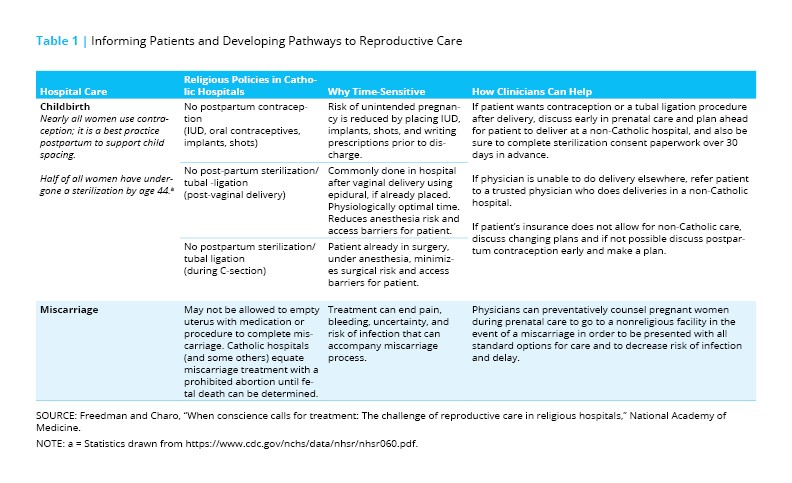

One way to begin to do this, and to do it in the least controversial and burdensome way, is to focus on transparency, information delivery, and referrals (see Table 1).

Transparency is essential because patients often have no idea that their medical and surgical options are limited due to a religiously motivated hospital policy. At a minimum, patients should not have their ability to exercise their own consciences – and make their own health choices – limited by a failure to properly inform them before they consent to treatment at a religious facility or before they purchase insurance usable only at such a facility. Clinicians of all types should be prepared to communicate which care is limited by institutional policy to help patients navigate the most direct path toward the care they want and need. While the law protects institutions’ right to restrict care according to religion, the individuals working in those institutions should be prepared to address patients’ potential ignorance of those care restrictions by taking extra measures to teach their patients where to find the care they cannot provide.

Regardless of religious affiliation, institutions are not entitled to interfere with an individual’s decision-making process. Information delivery is an essential element of providers’ professional duty to ensure that patients can make their autonomous decisions before giving informed consent. This is an obligation in common law, in state law governing medical practice, and in codes of practice, and it applies as much to institutions as to individual providers. Adequate information includes identifying all available options and clarifying whether they are available at that particular facility. It also includes information from insurers, so that patients can choose a plan that includes an institution willing to offer care they think they might want or need in the future.

These principles – the duty to fully and accurately explain options, to respect patients’ decisions, and to help patients get the services they’ve chosen – are currently at the center of a case before the Supreme Court of the United States. The court is considering whether a 2015 California law, known as the Reproductive FACT Act, violates the First Amendment right to free speech. The law requires that all licensed and covered health care facilities – including pregnancy crisis centers that do not provide abortion for religious reasons – inform patients that the state of California “has public programs that provide immediate free or low-cost access to comprehensive family planning services, prenatal care, and abortion, for eligible women” [8]. The Supreme Court decision, which could have significant ramifications for both patients and providers, is due in June 2018.

We maintain that referral is critical in cases involving health care workers who have a conscience motivation to provide care but are unable to offer those services themselves due to institutional restrictions. Referral allows these providers to fulfill the duty they feel they have to help patients access care sought under their own consciences and medical circumstances. Indeed, it may be difficult for patients to appreciate in real time the interplay between their preference and religious strictures without the guidance of interpretation of the clinician.

The challenges of differing religious beliefs can be mediated at times by ensuring that both patients and clinicians are able to pursue their own preferences. Institutions must be transparent, and clinicians must be allowed – even encouraged – to provide adequate information and referrals so that patients’ needs are not dismissed or deflected. Professional codes have long included a duty to provide patients with information and, in many cases, referrals. The American Medical Association’s Code of Medical Ethics, for example, states that even in the exercise of conscience-based objections, physicians must “uphold standards of informed consent and inform the patient about all relevant options for treatment, including options to which the physician morally objects” [9].

Our modest proposal doesn’t even go this far. We argue that employers and institutions should not be allowed to prevent providers from following their own religious beliefs and moral convictions when those beliefs lead providers to want to provide information and referrals. Nor should institutions be allowed to place obstacles in the way of patients who seek information and referrals they need to make decisions that accord with their own moral dictates. We must take the handcuffs off those whose consciences tell them to provide care. As President John F. Kennedy said, “If we cannot now end our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity” [10].

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! Patients may not realize they are at a religious hospital that won’t provide certain care. Authors of this Commentary state that employers should not be allowed to stop clinicians from providing information on and referrals to all healthcare options: http://ow.ly/s09p30jHpPn

Tweet this! Patients may not realize they are at a religious hospital that won’t provide certain care. Authors of this Commentary state that employers should not be allowed to stop clinicians from providing information on and referrals to all healthcare options: http://ow.ly/s09p30jHpPn

![]() Tweet this! Health professionals that work at religious hospitals but don’t share their institution’s religious objections to certain forms of care can still provide their patients all available information about care options and referrals to other institutions: http://ow.ly/s09p30jHpPn

Tweet this! Health professionals that work at religious hospitals but don’t share their institution’s religious objections to certain forms of care can still provide their patients all available information about care options and referrals to other institutions: http://ow.ly/s09p30jHpPn

![]() Tweet this! Authors of our newest NAM Perspectives Commentary encourage health professionals to focus on transparency, information delivery, and referrals when operating within a hospital that has religious objections to certain forms of care: http://ow.ly/s09p30jHpPn

Tweet this! Authors of our newest NAM Perspectives Commentary encourage health professionals to focus on transparency, information delivery, and referrals when operating within a hospital that has religious objections to certain forms of care: http://ow.ly/s09p30jHpPn

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2018. HHS announces new Conscience and Religious Freedom Division. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2018/01/18/hhs-ocr-announces-new-conscience-and-religious-freedom-division.html (accessed April 21, 2018).

- Uttley, L., C. Khaikin, and P. Hasbrouck. 2016. Growth of Catholic hospitals and health systems: 2016 update of the Miscarriage of Medicine report. Available at: http://static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/816571/27061007/1465224862580/MW_Update-2016-MiscarrofMedicine-report.pdf?token=%2BvYV7WHdaTIVy2u2vvEHorNIF44%3D (accessed April 21, 2018).

- Uttley, L., S. Reynertson, L. Kenny, and L. Melling. 2013. Miscarriage of medicine: The growth of Catholic hospitals and the threat to reproductive care. Available at: http://static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/816571/24079922/1387381601667/Growth-ofCatholic-Hospitals-2013.pdf?token=JkH0OjBCk63dOSJ8ftNS0pmSdJw%3D (accessed April 21, 2018).

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. 2009. Ethical and religious directives for Catholic health care services, 5th ed. Washington, DC.

- Freedman, L. 2010. Willing and unable: Doctors’ constraints in abortion care. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

- Freedman, L. R., and D. B. Stulberg. 2013. Conflicts in care for obstetric complications in Catholic hospitals. AJOB Primary Research 4:1-10. Available at: https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/assets/conflicts_in_care.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Freedman, L. R., L. E. Hebert, M. F. Battistelli, and D. B. Stulberg. 2018. Religious hospital policies on reproductive care: What do patients want to know? American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 218(2): 251.e1-251.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.595

- Reproductive FACT Act (passed Oct. 9, 2015). Available at: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160AB775.

- American Medical Association. 2018. AMA code of medical ethics. Available at:https://www.ama-assn.org/deliverying-care/physician-exercise-conscience (accessed April 21, 2018).

- Kennedy, J. F. 1963. Commencement address at American University. Available at:https://www.jfklibrary.org/%20Asset-Viewer/BWC7I4C9QUmLG9J6I8oy8w.aspx (accessed April 21, 2018).