Third Annual DC Public Health Case Challenge: Supporting Mental Health in Older Veterans

In 2015 the National Academy of Medicine and the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) held the third annual District of Columbia (DC) Public Health Case Challenge (http://nam.edu/initiatives/dc-public-health-case-challenge/), which had its inaugural year in 2013 and was both inspired by and modeled on the Emory University Global Health Case Competition (http://globalhealth.emory.edu/what/student_programs/case_competitions/index.html).

The DC Case Challenge aims to promote interdisciplinary, problem-based learning in public health and to foster engagement with local universities and the local community. The Case Challenge engages graduate and undergraduate students from multiple disciplines and universities to come together to promote awareness of and develop innovative solutions for 21st-century public health issues that are grounded in a challenge faced by the local DC community.

Each year the organizers and a student case-writing team develop a case based on a topic that is relevant to the DC area and has broader domestic and, in some cases, also global resonance. Content experts are then recruited as volunteer reviewers of the case. Universities located in the Washington, DC, area are invited to form teams of three to six students, who must be enrolled in undergraduate or graduate degree programs. In an effort to promote public health dialogue among a variety of disciplines, each team is required to include representation from at least three different schools, programs, or majors.

Two weeks before the Case Challenge event, the case is released, and teams are charged to employ critical analysis, thoughtful action, and interdisciplinary collaboration to develop a solution to the problem presented in the case. On the day of the Case Challenge, teams present their proposed solutions to a panel of judges composed of representatives from local DC organizations as well as other subject matter experts from disciplines relevant to the case.

2015 Case: Supporting Mental Health in Older Veterans

The 2015 case focused on how to enhance the quality of life of older veterans (aged ≥ 65 years) by improving their mental health and well-being. The case asked the student teams to develop a program with a grant of $1.2 million over five years that would fill a void in interventions intended to support veterans in transitioning back to civilian life, promote the well-being and mental health of veterans throughout the course of their lives, and provide long-term solutions and gains. Each proposed solution was expected to offer a rationale, a proposed intervention, an implementation plan, a budget, and an evaluation plan.

The case framed the issue through five scenarios portraying a range of issues faced by older veterans. Though the five illustrative scenarios were fictional, they drew from actual circumstances faced by veterans in DC. In the first scenario, a Vietnam War veteran who had handled difficult tasks, such as prepping fallen or seriously ill soldiers for transport to the United States, later experienced difficulty sleeping and connecting with family and friends. He felt that he had to deal with these issues on his own, and his symptoms worsened. He was later diagnosed with PTSD but struggled with continuing treatment due to feelings of shame. The second scenario described a primary care physician at the Washington DC VA (Veterans Affairs) Medical Center. In her practice, she regularly came across older veterans who were “down in the dumps” and withdrawn. She did not feel qualified to treat these symptoms, and her patients were resistant to seeking the help they needed due to the stigma associated with mental illness. The third scenario looked at a retired World War II veteran whose leg was partially amputated during his service. He became withdrawn, started abusing prescription drugs and alcohol, and was resistant to treatment. He and his family felt they did not have any resources to which to turn. The fourth scenario centered on Fayven Jackson, who experienced mental health challenges prior to enlisting in the army during the Korean War as an administrative secretary. Fayven grew up in foster care and had a very small social network. Due to depression, she served in the army only a short time. She felt she did not have many resources and did not try to access the VA system because she was not sure if she was eligible. The final scenario looked at John Kim, a second-generation American veteran who joined the US Marines during the Vietnam War directly after graduating from high school. He was an exemplary serviceman with a bright future. Unfortunately, Kim’s family had no way to survive financially without his contributions. This played a role in his heavy anxiety. He was unable to separate family and work, and left service. His health declined steadily, and after a series of low-wage jobs, he never had the opportunity to further his education and advance his career.

The teams were provided with background information that included national and DC demographics; population statistics on veterans as well as statistics specifically for DC veterans; government services available to veterans, including health services; and important considerations for health in older adults, including information on transportation, socioeconomic status, Social Security, homelessness and poverty, educational attainment, employment, technology and aging, mental health, and substance abuse.

Team Case Solutions

The following brief synopses prepared by students from six of the teams that participated in the 2015 Case Challenge describe how teams identified a specific need in the topic area, how they formulated a solution to intervene, and how they would implement their solution if they were granted the fictitious $1.2 million allotted to the winning proposal in the case. Team summaries are provided in alphabetical order. Not all teams submitted a summary of their solution for this publication.

The 2015 Grand Prize winner was American University. Three additional prizes were awarded: two Practicality Prizes, to the teams from Georgetown University and the George Washington University; and the Creativity Prize, to the University of Maryland, Baltimore, team.

American University

Team members: Bailey Cunningham, Alexa Edmier, Madison Hayes, Caroline Sell, Hana Stenson, Shreya Veera

Problem

Our approach to mental health in older veterans addresses what we believe are the three biggest barriers to optimal mental health in older veterans: lack of access to existing resources, the absence of a strong support system, and transportation difficulties.

Mission

The Open Door aims to connect aging heroes to a healthier tomorrow. Our mission is to use nontraditional methods to connect aging veterans to community and resources in DC to better their mental health and overall well-being.

Theory

We based our program on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory. We believe that it is important to address the basic needs of veterans before we can address their psychological and self-fulfillment needs. Therefore, our organization takes a holistic approach, connecting them to the resources they need to fulfill their basic needs while providing them with a sense of community. The Open Door believes that building this foundation is vital to addressing the long-term mental health needs of the veteran community.

Overview

The Open Door is based on a three-pronged approach that uses our resource map, peer-to-peer mentoring program, and mobility team to best connect and assist veterans in need (see Figure 1). Our target population is veterans over the age of 65 living in DC. Through our program, we hope to connect these veterans to existing organizations in DC that can provide for their physical and mental well-being, foster a sense of community through support groups, and involve them in research-informed peer-mentoring and social programming. We hope to ensure that veterans have access to and an understanding of the resources available to them, regardless of age or mobility level.

Figure 1 | Program Overview of the Open Door’s Three-Pronged Approach

Mentoring Program

The first part of our program is based on a support and mentoring program (see Figure 2), as we believe that a veterans-helping-veterans approach will be the most effective in helping homeless veterans connect to resources and in creating a sense of community. We applied this model to our approach to build a support system for veterans run by veterans. The Open Door will have support groups designed by the employed director of the center and led by our staff. These support groups will meet regularly and will be followed by social activity nights, which will include cooking or painting classes, to encourage program retention rates. It is important to note that while staff members will design and oversee the program, the key element is having volunteer veterans who will make this mentorship program meaningful to the veteran participants. Additionally, there will be a 24-hour emergency housing and mental health service hotline that works on an on-call basis to provide continuous support for those enrolled in the program.

Figure 2 | Components of the Open Door’s Support and Mentoring Program

Mobility Team

The main goal of part two of our program is to provide veterans who are unable or prefer not to leave their homes with access to health services. Our mobility team, a group of volunteers led by hired mobility team leaders, will first represent our organization at community locations and events (such as community centers and local farmers markets) to inform potential participants about our services. During this initial advertisement period, it will also be important to reach out to other organizations that work specifically with our target population (such as DC area hospitals, geriatric doctors, and military-specific retirement homes), where staff can distribute our informational brochures. Our mobility team can then respond to house calls to DC community veterans who cannot leave their homes due to physical disability or their preference not to come to our center because of mental health concerns. On site, our mobility team will be able to perform the same needs assessment that participants would get at our center, and they can be connected to sought-after health services with our online resource map. Once they have been connected, we will encourage them to attend our in-house mental health programming to build the feeling of a strong veteran community, and we hope they will return to volunteer with our program.

In addition to this accessibility project, we plan to further develop our homeless veterans project. Whenever staff encounter a homeless veteran, we will have the resources to bring them back to our center, where they can receive the same in-house services we offer our traditional participants. We can provide access to veterans services, and we will also be able to connect them to community resources to help them find food and housing.

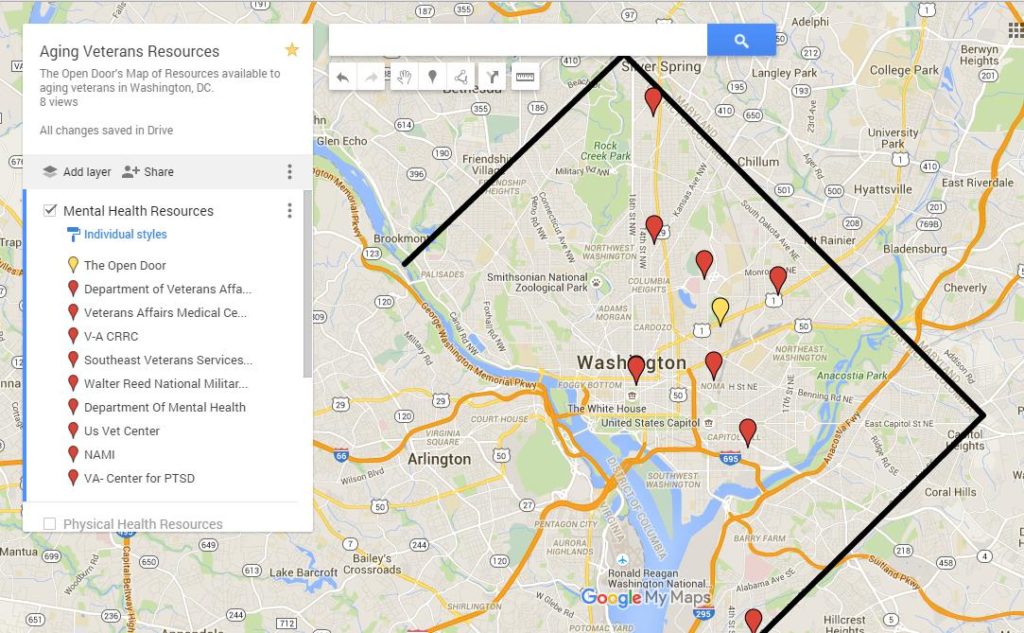

Resource Map

Our research indicates that one of the main challenges of navigating veteran resources is finding the resources in the first place. The DC area has an extensive existing network of veteran health resources, yet they are underused. We decided an appropriate tool to bridge this gap would be an online resource map specific to those over the age of 65. The goal of this tool is to provide those who are not mobile or who are not comfortable leaving their homes with the same access to resources as their peers. The tool begins with a simple set of questions determining veteran status, age, location, need, etc. After answering the questions, the veteran is directed to the resource map, which ranks the organizations that would best suit them and displays the resources as pins on a map (see Figure 3). Once the veteran selects an organization, the map prompts a question to ensure the veteran has transportation to those services. The resource map would be supported by both a technology consultant and an in-house benefits coordinator.

Figure 3 | Sample of the Open Door’s Veteran Resource Map

Goals

The overarching goals of our program are to establish professional connections with DC organizations that aim to help aging veterans, such as housing and mental health services organizations, and to create a sustainable program by using a veterans-helping-veterans approach in our mentoring sessions. We want to create a community where veterans feel safe, welcome, and supported, especially regarding the somewhat taboo subject of mental health.

Evaluation

We will evaluate the Open Door using four approaches. We will begin by completing a formative evaluation at the start of the program. We will assess the exact needs of our veteran population through surveys. During the program, we will complete an ongoing process evaluation through surveys and focus groups. This will provide the Open Door with feedback, so we can constantly improve services. Impact evaluations will be completed at the end of each year using focus groups and written assessments. Finally, we will have outcome evaluations in the form of focus groups, to assess the overall change in DC veterans’ mental health since the start of the program.

Sustainability

The Open Door will create a sustainable model using four methods: (1) partnering with other nonprofits that have similar missions, (2) involving the community in our program through volunteer opportunities, (3) using veteran leaders in our program to build trust within the military community, and (4) asking corporate sponsors to make donations to fund the organization past the end of the grant.

Conclusion

We believe that our program model will not only address the immediate needs of our veteran participants, but it will also reach deeper into and strengthen the DC veteran community. Every part of our program is designed to support veterans in their own unique ways while bringing everyone together as a reminder that, despite how one may feel, no one is ever truly alone. The Open Door is dedicated to serving and bringing veterans into our community and our family, and we hope that the rest of the DC community will begin to better recognize the veteran population through our work.

George Mason University

Team members: Jumoom Ahmed, Kaltun Ali, Catriona Gates, Hana Hanfi, Maryama Ismail, Zeinab Saf

VetNet D.C. brings together 50 veterans age 65 and older in the DC metropolitan area by connecting them through a biannual five-month program. The network is centered on social activities and mental health awareness and intends to improve the quality of life of the elder veteran population. By enabling access to preexisting resources, we will help veterans improve their social lives and mental and physical health.

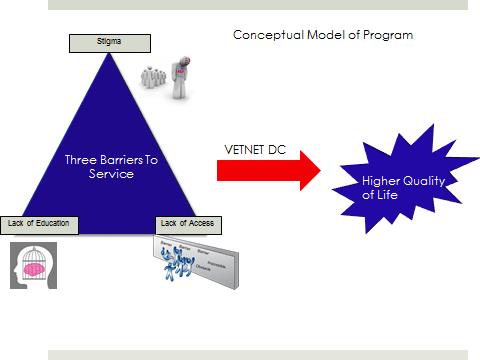

VetNet D.C. was created on the belief that there are three barriers that prevent elderly veterans from reaching the resources they need: stigma surrounding mental illness, a lack of education about mental illness, and a lack of access to health care services. By tackling these three barriers through VetNet D.C.’s five-month program, we believe that the quality of life of elderly veterans can increase exponentially (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 | Conceptual Model of VetNet D.C.

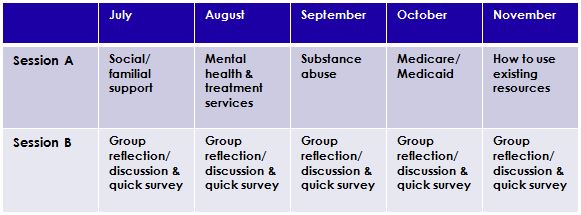

In addition to VetNet D.C.’s Plan of Attack (see Figure 5), the program will also provide a website forum that will serve as a social network for veterans to connect. Monthly meetings will be divided into Sessions A and B, with Session A focused on providing the activities and Session B allowing for an open discussion of the activity (see Table 1). Session B’s reflection period also provides a venue for program evaluation.

Figure 5 | VetNet D.C.’s Plan of Attack

Table 1 | Sample Outline of Monthly Meetings

VetNet D.C. will partner with Mary’s Center, which will provide the necessary facilities for holding meetings twice a month. Another partner will be a Gold’s Gym near Mary’s Center, which program members can use at a discounted to free rate in preparation for either the Pacers Running (the third VetNet D.C. partner) Veterans Day 10K & Tidal Basin Fun Walk or the Memorial Day 10K walk/run.

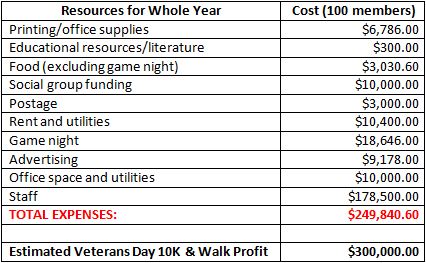

Each year, $250,000 will be allocated to running the program (see Table 2). The largest program cost will be employee salaries, which will add up to approximately $179,000 a year. The lowest cost will be educational resources and literature for the program members, which will cost around $300. For the first year, about $10,000 will be spent to advertise the program, and another $10,000 will go to office space and utilities, including website maintenance.

Table 2 | Brief Budget Outline of Annual Expenses and Profit

We recognize that a potential barrier to program success is not generating enough interest within the target population. As such, tactful advertising approaches must be made to combat this challenge. Not only will advertising be necessary for gathering the target population, but it will also be paramount for the annual Veterans Day and Memorial Day walks/runs, to keep the organization sustainable.

Georgetown University

Team members: Andrew Hong, Claire Hong, Ryan Jeffrey, Caroline Kim, Julia Michelle White

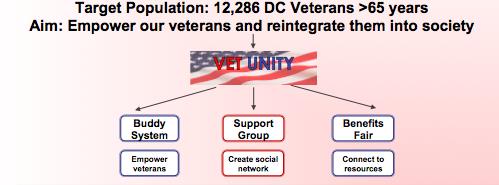

According to the World Health Organization, mental health is an all-encompassing concept, “a state of complete mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease” [1]. Therefore, the Georgetown University team made our goal to improve the mental health and quality of life of all DC veterans over 65 years old, a population of approximately 12,286 people. To achieve this goal, the Georgetown University team created Vet Unity, a nongovernmental organization with a three-pronged approach to tackle three specific challenges (see Figure 6).

Figure 6 | Target Population, Aim, and Intervention Components

Addressed by the first prong is the fact that many resources providing services and benefits to veterans are not being fully used. There are two main reasons behind this low use. First, services offered by government and nonprofit organizations form a fragmented web of resources, and many veterans are unaware of the existing programs. Second, older veterans are limited by lack of transportation to reach these programs. Therefore, Vet Unity proposes the creation of biannual benefits fairs to connect veterans to existing organizations. Volunteer services—including vision and blood pressure checks, and free haircuts—provide incentive to attend. These fairs will be open to all veterans and held at DC parks and recreational facilities in the northeast and southeast quadrants of the city—areas that have the largest populations of veterans and the greatest transportation challenges.

The second prong addresses the stigma of mental illness and its role as a major barrier to the recognition and treatment of mental illness. To handle this challenge, Vet Unity proposes the creation of sponsored social groups for veterans. Each group will be composed of 10 to 20 veterans who meet weekly at local locations such as places of worship or community centers. The major goal of these groups is to create a social network for these aging adults and provide them with a space to discuss their experiences and struggles. To identify and discuss a stigmatized topic such as mental health, trust among group members is essential. Groups will be led by peer support specialists who are trained to facilitate conversations and act as the connection to professional mental health resources. Each group is given a small stipend to cover supplies, food, and activity costs, with spending to be determined by each group.

Although the first two programs of Vet Unity are targeted to the aging veteran population, the third program, the Buddy System, pairs older veterans, as mentors, with younger returning veterans. The Buddy System features two benefits. First, the older veterans gain responsibility by taking on an active role. Second, the program improves the mental health of the younger generation during the critical period of return from combat.

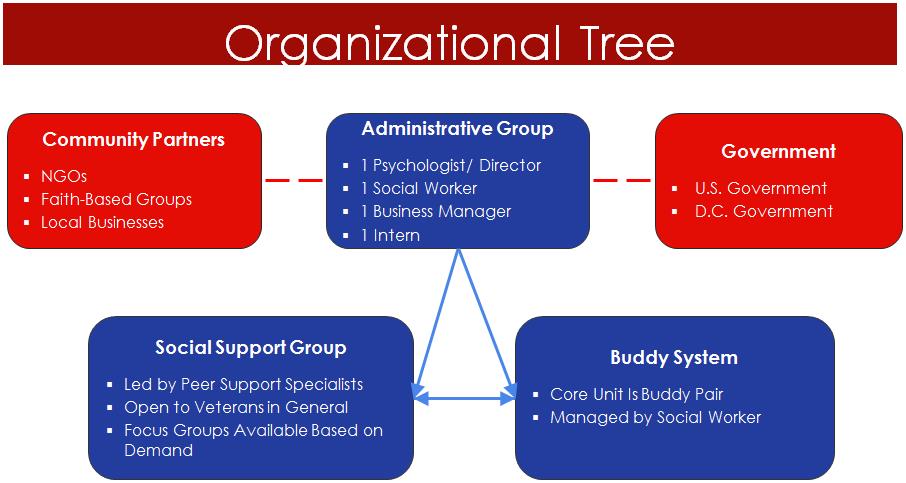

Vet Unity has a $1.25 million budget for its launch and first five years of operation. Half of this budget will be allocated to employment and benefits of staff members, which include a part-time medical director, business manager, and social worker. Twenty percent of the budget will be allocated to stipends for the support groups. The remaining 30 percent will provide for marketing, business operations, purchase of a van for transportation, and evaluation of programs. See Figure 7 for an overview of Vet Unity’s organization.

Figure 7 | Vet Unity Organizational Tree

The George Washington University

Team members: Haneen Abudayyeh, Claire Houterman, Alexander Ives, Elisabeth Kutscher, Miranda Kuwahara

Overview and Goal

The Community Heroes and Mentor Peer Support (CHAMPS) is an intergenerational pilot program aimed at promoting resilience, optimism, and well-being in older veterans across DC. In partnership with veterans organizations and local universities, CHAMPS brings together veterans across generations to work on service projects.

Intervention

The CHAMPS program is built on the principles of positive psychology, a subfield of traditional psychology [2]. Traditional psychology focuses on diagnosing and treating mental illness. Positive psychology augments this important work by investigating the strengths that individuals possess and how individuals can tap into those strengths to lead a more fulfilling life. CHAMPS’s positive psychology approach amplifies the work of the many excellent DC area programs to address older veterans’ mental health.

The CHAMPS program will recruit an initial group of approximately 30 older and younger veterans. We will seek to begin our work with older veterans from Knollwood Military Retirement Residence, a residential home for retired officers and their family members. Many of these veterans are already connected with services. However, research suggests gaining the trust of veterans and avoiding stigmatizing mental health when working within their community [3,4]. Informed by this research, the CHAMPS program will start with this core group to build credibility. Younger veterans will be recruited from various organizations, including university veterans offices and student groups. Ultimately, as we expand over a five-year period, we aim to reach DC veterans who are not currently connected with mental health services.

Participating veterans, both older and younger, will come together once per week to work together on a service project of their choosing. The goal is for veterans to approach each project as a mission by assuming leadership roles as they meet the needs of their community. In addition to focusing on the service project, each weekly meeting will include a short workshop component that introduces veterans to specified positive psychology skills, such as increasing optimism or understanding mind-sets. These workshops will be loosely based on Master Resilience Training, a positive psychology training that is currently used by the US Army [5]. The CHAMPS program will recruit top-achieving students from DC area universities and train students to facilitate these workshops. Student interns will also receive veteran- and cultural-sensitivity training.

Budget

In years one and two, the majority of our financial resources will go toward the salaries of our project administrator and program consultants, who will be involved in the curriculum planning for the weekly workshops. A sizable portion will also go toward transportation fees so that we can transport CHAMPS participants to and from their project sites. In the final three years, our budget will shift to provide better support for CHAMPS participants and to evaluate the impact of the program on the well-being of participants. Consultant salaries will increase beginning in year three to allow for evaluation of the CHAMPS program’s intended outcomes. We have also budgeted for higher transportation costs, as more veteran-initiated service projects are expected to begin in the later years of the pilot program. Finally, we have budgeted for a technology component to expand the CHAMPS model to veterans in other parts of DC and in other cities. We hope to use technology to connect the first CHAMPS site with other locations and enable a larger network of like-minded veterans to be united.

Evaluation and Intended Outcomes

We intend to evaluate our short-term goals with the use of a qualitative focus group that will occur at the end of program years one and two. Following the focus groups, we will phase in quantitative measures, such as anonymous pre- and post-intervention surveys.

Throughout the five years of the grant, we will collect data on outcomes related to our peer support group, such as quality-of-life measures; recovery attitudes; and perceptions of empowerment, self-confidence, and self-esteem. We hope to engage with veterans of all walks of life who have had diverse military experiences and consequently will measure feelings of military and veteran connectivity.

The purpose of evaluation throughout the five-year program is to use our compiled data to assess the strengths and limitations of CHAMPS and to ensure that the program aligns with the participants’ wants and needs. Based on the qualitative and quantitative data, we will alter CHAMPS as we see fit to reach our goals and the goals of our participants.

Conclusion

The CHAMPS program provides a unique integration of service project and positive psychology components, which will serve to strengthen the entire community. Partnerships with DC area universities will support the development of a new workforce that will have a deeper understanding of the needs of older veterans. At the same time, veterans across generations will benefit from a shared sense of mission, deepening the improvement of their overall well-being.

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

Team members: Jason David, Morgan Harvey, Laura Kropp, Kalpana Parvathaneni, Edwin Szeto, Kristin Wertin

Problem, Goal, and Intended Outcomes

Aging veterans face numerous barriers to seeking treatment for mental illness. Our intervention intends to specifically address the issue of stigma surrounding mental health and its treatment. Furthermore, our intervention will address the current lack of coordination among primary care, mental health, and aging service providers. The goal of our intervention is to reduce stigma and improve the mental health and well-being of aging veterans by building peer-to-peer relationships within the veteran community. Our overall outcomes are to show a demonstrable increase in positive attitude regarding mental health treatment within the veteran community, increase use of mental health resources, and increase long-term well-being for veterans in the community.

Intervention

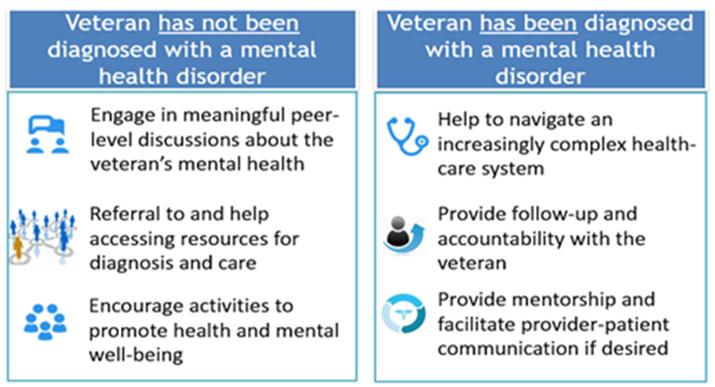

To achieve the stated outcomes, we intend to create a peer-to-peer mental health navigator program in the veteran community, known as INVOLVED: Veteran Navigators of DC. Navigators will be matched with aging veterans who (1) have been diagnosed with a mental health condition or (2) are exhibiting risk factors for mental illness but have not yet been diagnosed. The navigator and the veteran will work together to address barriers to care, discuss concerns about stigma, and assist with the navigation of mental health benefits and services.

There is strong evidence of the efficacy of peer-to-peer navigator programs [6,7]. Peer-to-peer navigator programs take advantage of the innate relatability and trust that come from addressing sensitive issues with a member of one’s peer community, with whom one might have shared experiences and a common veteran-specific cultural awareness [8]. By doing so, the peer-to-peer navigator model brings unique treatment advantages to the patient, translating into documented quantitative improvements in the mental health of program recipients, including Global Assessment of Functioning scores, community integration, quality of life, reduction in distressing symptoms and days of hospitalization, and feelings of general empowerment among patients [9]. Furthermore, peer-to-peer navigator programs provide growth opportunities for the navigators themselves. In fact, many times, the navigator role is used as the final step in a patient’s recovery and maintenance of well-being.

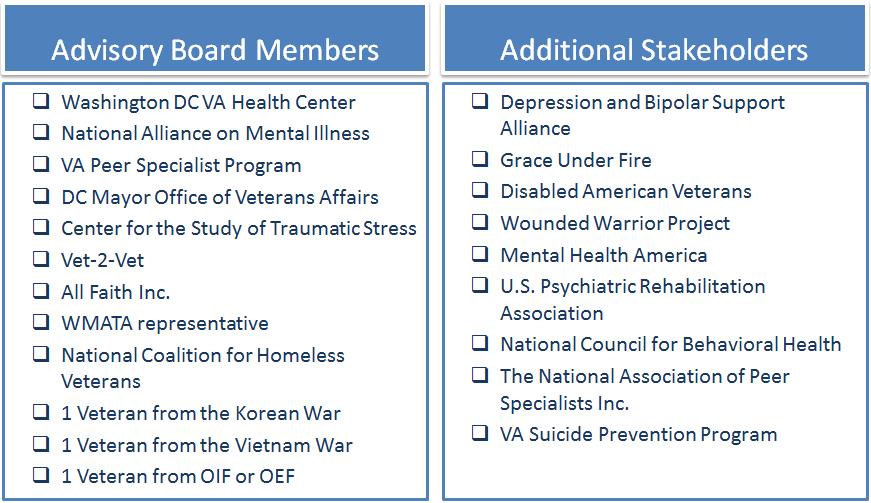

There are specific characteristics we look for in the profile of a potential navigator, namely that the navigator be a veteran; have reliable lodging, income, and transportation; and have strong communication skills. Specifically, navigators will not be counselors but referral experts. They will be trained in recognizing the warning signs of mental illness, will be part of a veteran’s peer group, and will work with veterans with their informed consent. Training will be facilitated through potential partners and stakeholders from the advisory board (see Figure 8).

Figure 8 | Advisory Board and Stakeholders

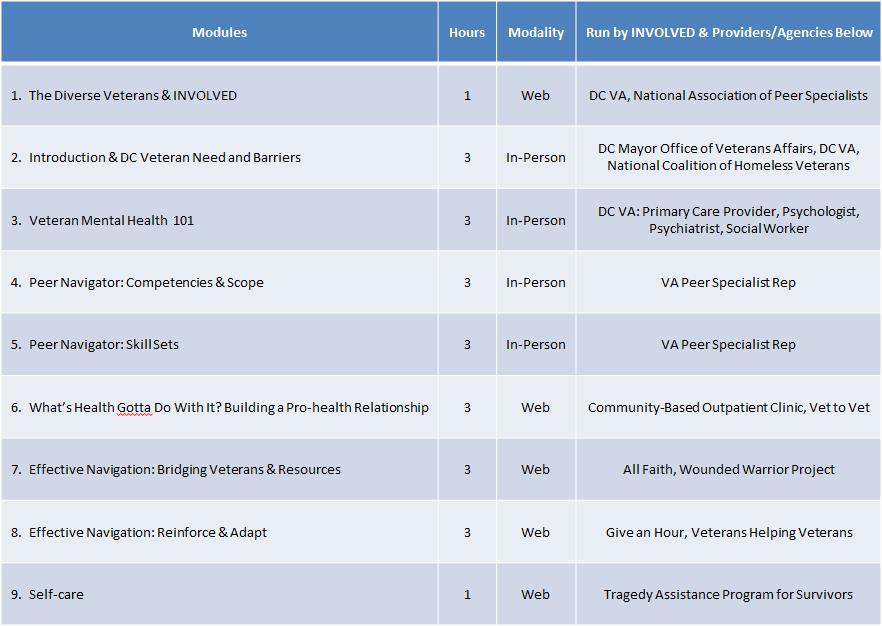

Our advisory board will consist of a multidisciplinary team that includes members from transportation, local government, and health providers, and they will help guide and make decisions related to our program goals. Trainings will follow a module-based program that potential navigators must complete before being allowed to connect with program recipients (see Table 3). Specifically, the navigator intervention will reach the target population via two approaches, one for recipients already diagnosed with a mental health illness and another for those exhibiting risk factors (see Figure 9). Likewise, two different intervention strategies will be employed for the different program recipients (see Figure 10).

Figure 9 | Strategies for Reaching the Target Population

Figure 10 | Navigator Interventions

Table 3 | Potential Training Modules

The projected budget for our intervention over five years is $1.2 million. The budget includes salaries and fringe benefits for staff, and navigator curriculum development, navigator incentives, and overhead. Our staff will consist of two personnel. Based on average salaries in the DC metro area, we allotted $80,000 per year to hire a full-time equivalent (FTE) program coordinator. We also allocated $50,000 to employ a 0.5 FTE program evaluator. We plan to offer fringe benefits to our employees to reflect their experience and education level. Thus, we estimated the total expenditure on staff salaries and benefits per year to be $190,000. In addition, we plan to spend $73,750 to develop the curriculum to train our navigators. The remainder of our budget will be allocated to navigator incentives and overhead.

There are certain limitations to our proposal, which we have strategies to mitigate. Specifically, our scope in recruitment of DC veterans to the program may be limited to those veterans currently part of mental health wellness programs. We plan to use the wide reach of our current stakeholders and their networks to promote and increase the visibility of our program. Additionally, despite the program’s use of veterans as navigators, persisting stigmas about mental health may still preclude potential recipients from using our system. We intend to tailor part of our outreach toward friends and family members of veterans, with the intent to educate and create dialogue about

veteran mental health, which may alleviate existing stigmas.

In summary, our intervention will promote the mental health of aging veterans in DC. Veteran navigators will help us to (1) increase recruitment of veterans to our program, (2) provide one-on-one mentoring to veterans, and (3) streamline treatment of care for veterans with mental health issues. We believe that collaborating with existing entities that support veterans and mental health—such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness, Vet2Vet, and the VA—will allow us to integrate our program into an existing framework.

University of Maryland, Baltimore

Team members: Joshua Chou, Diana-Lynne Hsu, Brooke Hyman, Daniela Minkin, Lauren Whittaker

Introduction

Mental health in older veterans is an important DC public health concern. The National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics estimates that more than 50 percent of veterans living in DC are over 60 years old, representing a significant population [10]. Currently, there are only four VA service centers for the entire population of nearly 30,000 DC veterans. This presents a huge burden for the VA system. Additionally, access to VA services may be difficult for veterans to navigate. The access process is long, starting with the establishment of eligibility based on minimum duty requirements, to the receipt of assigned priority, and, finally, to access to providers. Nearly 60 percent of veterans are not covered by VA services for a variety of reasons, including ineligibility, internal and external stigma, and inability to access services due to lack of transportation and provider shortages. These issues provide a starting point for which direct interventions can take place.

Our program, SAVI-FAM, plans to address these challenges to improve mental health in older veterans. SAVI-FAM stands for Supporting Aging Veterans via Interdisciplinary Focused Assessment and Management. Our goal specifically is to serve as a bridge between mental health care providers and aging individuals who have served our country. SAVI-FAM’s priorities are to

- provide a safe space for veterans to give and receive psychosocial support,

- identify patient needs to increase patient self-awareness and provide culturally sensitive solutions, and

- foster a community of mental wellness among aging veterans.

Phase I

By partnering with a nearby emergency room (ED) at a university-affiliated hospital, our project can target veterans age 65 and older who may not be using the VA system to their greatest benefit.

A study of veterans reported that societal and self-imposed stigma were significant barriers to accessing mental health care. Specifically, many veterans cited a preference to speak with family or friends instead of clinicians. Another problem was lack of perceived need, such that many veterans were not aware that they were suffering from symptoms of mental illness. We propose that veterans who might otherwise feel reluctant to engage with mental health professionals may be more willing to open up to a professional who has also served in the military. Relatedly, social work is becoming an increasingly popular field of study for veterans receiving higher education, and therefore we can capitalize on the rapport built when linking an at-risk veteran with another veteran social-work student (SWS).

At registration in the ED, there will be an additional question for patients 65 and older: “Have you ever served in the military?” Patients prescreened as 65 and older and who have served in the military will be given an additional HIPAA form authorizing the release of their medical records to our program. From that original pool of patients, the SWS can target those with pending discharges. After introducing him or herself, the SWS will administer two screening tools: the Beck Anxiety Inventory–Primary Care (BAI-PC) instrument and the CAGE questionnaire (which is an acronym for its four questions regarding cutting down on, annoyance with, and guilt about drinking; and drinking as a morning eye-opener) [11,12]. The purpose of these tools is to quickly identify the most prevalent mental disorders that have been found in veterans, such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and alcohol abuse. We selected these tools for their brevity, sensitivity, and specificity. Also, the BAI-PC is a measurement tool that is already used and promoted by the VA [11]. Patients scoring high on either tool will be encouraged to join the SAVI-FAM program, as will veterans who are admitted to the ED four or more times in a year. Use of an ED four or more times a year is likely indicative of misuse of health care services and/or lack of access to a primary care physician for any number of reasons. In targeting these particular patients, the draw to join SAVI-FAM will be its social milieu and private affiliation, differentiating our program from existing ones like VA clinics and centers.

Phase II

At SAVI-FAM, the ultimate goal is to ensure that all program participants have access to health care, particularly behavioral services. For instance, during open enrollment, we would provide assistance to veterans to help them enroll in Medicare or Medicaid programs, searching specifically for programs that would best suit their needs. For veterans who are eligible or already have VA benefits, we would work to connect them with local VA health centers and community outpatient-based clinics. Most importantly, we would help veterans within our program locate a primary care provider, as it is essential for each veteran to have a physician consistently advising on their health status.

In addition to ensuring that participants have access to health care, SAVI-FAM strives to improve the quality of life for each participant, and we want to make sure that each participant is given an opportunity to live life with companionship, joy, and purpose. By providing social support and services, we believe that we will be able to create a place where these goals can be met. For example, we intend to host social events and activities (such as bingo nights, art workshops, and performances) to create a social space to foster community among veterans. Additionally, we propose to provide group therapy sessions that will create a safe environment in which veterans can come together to learn strategies to manage medication and cope with issues such as traumatic events and addictions. In summary, by providing increased access to care for veterans and by creating a space for veterans to interact with and support each other, we believe that we will help meet the mental health needs of veterans.

Phase III

Moving forward, we would like to expand our health care services to better meet the needs of our veterans. Our hope is to employ an interdisciplinary health care team (consisting of a geriatrician, nurse practitioner, social worker, pharmacist, and mental health liaison), as we believe that addressing mental health requires a multifocal approach with expertise from different health care professionals. This team will provide services such as medication management and reconciliation, coordination of veterans’ health care, immunizations, and point-of-care testing. Moreover, we hope to partner with local health care professional schools—including those at the university-affiliated hospital already involved with SAVI-FAM—to provide valuable field experience for students and increase opportunities for local schools to become involved in meeting the needs of their communities.

Personnel Requirements

To fulfill SAVI-FAM’s goals, the program requires personnel with very specific skill sets. Operational hours for the SAVI-FAM office would be 30 hours per week (open six days a week for approximately five hours each day) with somewhat staggered hours to ensure that aging veterans on different time schedules can be accommodated. Part-time employees are expected to work 15 hours per week (unless otherwise noted), and full-time employees would work the full 30 hours per week. Because we are focused on mental and behavioral health, and serve only an advisory role on other health matters, we would require one part-time mental health counselor and two mental health and substance abuse social workers (one part time and the other full time). As mentioned previously, we prioritize employing social workers who have either served in the military or have been specially certified for advising veterans, so that there is a higher level of understanding between our staff and our members. SAVI-FAM requires the employment of one social and human health service assistant (full time), to help connect our members to

available health care resources in the community, and one social and community service manager (full time), to coordinate SAVI-FAM events and programs. Finally, to ensure that our members are receiving the health care services they require, our office requires one nurse practitioner, who will serve as a primary liaison between our members and their health care providers, as needed.

Outcomes

Overall, our program is intended to decrease the number and frequency of ED visits, hospitals admissions, and readmissions at non¬–VA affiliated hospitals. To measure our program outcomes, we are using the Quality of Life Scale developed by John Flanagan. The scale comprises 15 questions that assess five categories: physical well-being, relationships with others, community and civic activities, personal development, and recreation. We intend to administer this scale to our members to evaluate their well-being at three-month intervals. This data will help our program identify our community’s needs and ways to improve services. Additional outcomes measures will include monitoring the number of hospital admissions and readmissions for our members, the frequency of ED visits, and the number of uninsured members throughout the year.

Conclusion

Follow-Up Event

To continue engagement of the student participants in the Case Challenge subject matter and in its practical application in the local community, the National Academies convened a follow-up event to the competition in March 2016. The event was an opportunity for university students to hear about the realities of implementing programs for veterans and to get more exposure to real-world local work. It was also an opportunity to build connections among the National Academies, the local DC community, and up-and-coming public health professionals from undergraduate and graduate programs at DC universities. The 2016 follow-up event highlighted the work of Washington, DC, agencies and organizations working to improve outcomes for veterans in the city. The day focused on two themes that emerged from the student solutions to the Case Challenge: addressing social needs of veterans to promote mental health and connecting veterans to service providers to improve mental health. The event brought together panels of DC-based nonprofit organizations that work on veterans issues and those with relevant roles to improve veterans’ health (such as the transportation sector and those who work with the homeless population).

Three teams from the competition were invited to present to the panels their solutions in the two focus areas. The event served as an opportunity for experts on these topics to engage with the students in a rich discussion on how to improve their proposed solutions and inform action to improve the mental health of aging veterans in Washington, DC.

Future Plans

The Case Challenge and follow-up event have brought the work of the National Academies to both university students and to the DC community. The National Academies are therefore committed to continuing this activity with the 2016 Case Challenge, which will focus on the changing American city and implications for health and well-being of vulnerable populations in Washington, DC. It will be sponsored and implemented by the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, with the support of the NAM’s Kellogg Health of the Public Fund and the engagement of related activities of the National Academies, including the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education. The National Academies staff continue to look for new ways to further involve and create partnerships with the next generation of leaders in health care and public health, and with the local DC community through the Case Challenge.

References

- World Health Organization. 2014. Mental health: A state of well-being. Available at: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en (accessed December 28, 2015).

- Seligman, M. E., and M. Csikszentmihalyi. 2000. Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist 55(1):5-14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

- Kim, P. Y., T. W. Britt, and R. P. Klocko. 2011. Stigma, negative attitudes about treatment, and utilization of mental health care among soldiers. Military Psychology 23:65-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2011.534415

- Vogt, D. 2011. Mental health-related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: A review. Psychiatric Services 62(2):135-142. Available at: https://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/ps.62.2.pss6202_0135 (accessed August 31, 2020).

- Reivich, K. J., M. E. Seligman, and S. McBride. 2011. Master Resilience Training in the U.S. Army. American Psychologist 66(1):25-34. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021897

- Greden, J. F., M. Valenstein, J. Spinner, A. Blow, L. A. Gorman, G. W. Dalack, S. Marcus, and M. Kees. 2010. Buddy-to-Buddy, a citizen soldier peer support program to counteract stigma, PTSD, depression, and suicide. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1208(1):90-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05719.x

- Jain, S., C. McLean, and C. S. Rosen. 2012. Is there a role for peer support delivered interventions in the treatment of veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder? Military Medicine 177(5):481-483. https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-11-00401

- Karel, M. J., M. Gatz, and M. A. Smyer. 2012. Aging and mental health in the decade ahead: What psychologists need to know. American Psychologist 67(3):184-198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025393

- Resnick, S. G., and R. A. Rosenheck. 2008. Integrating peer-provided services: A quasi-experimental study of recovery orientation, confidence, and empowerment. Psychiatric Services 59(11):1307-1314. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.11.1307

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2015. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics: Population table 4L: VetPop2011 living veterans by branch of service, gender, 2013-2040. Available at: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp (accessed October 9, 2015).

- Mori, D. L., J. F. Lambert, B. L. Niles, J. D. Orlander, M. Grace, and J. S. LoCastro. 2003. The BAI-PC as a screen for anxiety, depression, and PTSD in primary care. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings 10(3):187-192. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000136

- Morton, J. L., T. V. Jones, and M. A. Manganaro. 1996. Performance of alcoholism screening questionnaires in elderly veterans. American Journal of Medicine 101(2):153-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(96)80069-6