The Democratization of Health Care: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which called on more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States to provide expert guidance in 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which called on more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States to provide expert guidance in 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

Introduction

The US health care delivery system is in the midst of a transformation. For generations, it was rooted in a transactional, fee-for-service ethos that rewarded mainly interventions to treat individuals for diseases. Today, it aims to emphasize improvement in and maintenance of the health of both individuals and communities. The transformation presents the country with the opportunity to reconsider the role of patients and their families in health. Calls to “empower” patients—to change the traditional hierarchic relationships of health care—are not new but are now far more widespread (Topol, 2015). As in other industries, the availability of information and knowledge resources over the Internet has enabled people to take a more active role in managing their health and their health care and to make decisions that previously required highly trained professionals—in short, has enabled the democratization of health care (IOM, 2013a). Embracing that change not only will improve health outcomes but will address some of the underpinnings of the continued rise in health care costs and the maldistribution of professional resources.

How can health care be democratized? First, people must have a powerful voice and role in the decisions and systems that affect their health, and they need tools that help them to become far more actively engaged. Second, health professionals and institutions must value social equity and the individual in the context of community. With those principles, we can move from patient-centered health care—focused on sickness, medical interventions, and data on the average patient—to person-centered health care—motivated by wellness, supportive social conditions, and knowledge about the individual and his or her environments.

Those notions underlie the vision of a culture of health—a society in which all people have opportunities for better health where they live, work, learn, and play. Health is powerfully determined by our environments and our social circumstances—our income, education, housing, transportation, neighborhoods, and social and familial networks. As an example of how social determinants affect health, consider the holistic approach to health taken by Philadelphia’s Stephen and Sandra Sheller 11th Street Family Health Services.

Since the late 1990s, the 11th Street clinic has partnered with and served the residents of four public housing communities, where median family income is $15,000 and 80% of the people are covered by Medicaid or are uninsured. Many community members have experienced trauma of various forms, which compounds their acute and chronic health problems. Weaving together services to meet the physical, mental, spiritual, and social needs of patients makes the clinic a standout. During one visit, a 5-year-old can get immunizations and a dental checkup while a teen sibling participates in art therapy as part of an integrated mental health program. Parents and older adults, too, benefit from a variety of resources—including couples and family counseling, mindfulness training, cooking classes, and linkages to housing and food assistance—with comprehensive medical services. The 11th Street model is the exception, not the rule, but the arc appears to be bending in that direction.

We understand increasingly that we cannot achieve the three tenets of the Triple Aim—better health, better patient experience, and lower per capita cost—without the engagement of patients and families. We want people to embrace the transformed models of care and payment that we are building and to change their behaviors in fundamental ways. But for the most part, our current conversation and actions around engagement focus on how we get people, patients, and families to do what we want them to do. That perspective needs to change if our health care system is indeed to focus more effectively on improving the population’s health and health equity. The questions that we should be asking are, How do we build a health system that people want to and are able to engage in? How do we build a system that defines value through the lens of the people that it serves—a system that helps people to define the health goals that they want to achieve and then supports them in achieving those goals? Engagement must begin with accessible information and knowledge.

Health literacy is fundamental to democratization of health care. Fostering health literacy means aligning the demands and complexities of what is needed for health and health care with the skills and abilities of the public (IOM, 2013b). Hundreds of original research investigations have shown that health disparities depend on people’s literacy and numeracy skills, language, education, knowledge, and experience. Health systems routinely impose unnecessary complexity on patients, inasmuch as the design of most health care does not reflect the fact that half US adults read at or below an 8th- or 9th-grade level. Indeed, the current US health system is too complex to navigate at any educational level. Highlighting patient engagement and allowing it to guide the design and organization of evidence-based health care processes, practices, and research priorities can help to create content that is understandable, is navigable, and reflects patients’ needs. Only with a health-literate community can we engage in truly shared decision making.

People make decisions every day that have far greater effects on their health than decisions controlled by the health care system. Patients and their family caregivers are perhaps the most underused resource in improving health status and health care outcomes. The health care system has long been hamstrung by the episodic nature of in-person patient encounters that have generally been required if there is to be payment. Increasingly, however, technology can enable 24/7 contact and much greater levels of self-care. In addition to the health benefits to individuals of a more unified and integrated approach to health care, providing care in less expensive settings on a population scale has economic benefits. The key question is how to realize the substantial economic effects of patients’ and caregivers’ engaging with the professional health care team to manage patients’ health.

Properly and fully engaging individuals and families in managing and improving their health and the health of their communities is foundational to improving the health of Americans. In this paper, we explore a number of topics that are key to democratization of health care and propose policy recommendations to engage America in a journey to better health.

Key Issues

Creating a Culture of Health

Health systems will need to integrate physical health, behavioral health, and social-service delivery further to promote well-being optimally. Effective practice models of integration of primary care with behavioral health exist but have not yet been scaled, because of historical divisions in payment, practice, and culture. New payment models, such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services accountable health communities, have begun to allow health care dollars to be leveraged for social-service referral, navigation, and collaboration, but these strategies are nascent and need to be thoroughly evaluated. The behavioral health workforce and social-service system are inadequate, and foundational investment may be required to meet holistic needs identified by the health care system.

It is widely understood that the United States spends far more than any other country on health care services; what is less well appreciated is that many developed countries spend more on social services, which help them to achieve better social and health outcomes (Squires and Anderson, 2015). The current movement from volume-oriented to value-oriented payment provides incentives for health care payers and providers to examine anew how spending on supportive social services centered on the needs of the individual can reduce the need for higher-cost treatment in the medical care system. Poor housing, for instance, has direct effects on health via environmental exposures to (or protection from) lead, mold, vermin, and temperature extremes. Health care systems are beginning to experiment with models for paying for home remediation. The shift to person-centered health care will require a further commitment to communities, cross-sector collaboration, and systemic solutions.

Engaging Individuals and Families

A system that people want to engage in—a truly person-centered and family-centered system—will require a profound change in our health care culture and mindset and substantial change in payment approaches and care delivery. The most important change must come in how we think about the roles of patients and families. How can we expect to create a person-centered and family-centered system if their voices are not at the table, helping to create and evaluate the system? We must accept, value, and promote genuine collaboration in every dimension of our efforts to transform health care, including not just at the point of care but in design of care processes and payment strategies, governance bodies, policy development, and interfaces with the communities served. Transparency around costs and quality results are foundational to building trusted partnerships with people.

Economic Effects of Engaging Patients and Families

Under the current medical model, providers control both medical advice and the costs of health care. A democratized version of health care would have implications not only for outcomes but for costs. To achieve a state in which patients are more engaged, three key issues must be addressed. First, current patient-engagement efforts are fragmented. Employers, health care providers, payers, and other stakeholder groups are attempting to reach out to patients in different ways to encourage them to engage in a variety of activities: care coordination, wellness promotion, chronic disease management, medication management, and so on. Second, there is little effort to customize engagement strategies to patients’ needs, preferences, and motivations. There is insufficient attention, for example, to patient literacy, theories of behavior change, and behavioral economics. Third, patient-engagement efforts have not been integrated into the fabric of everyday life. We ask patients to manage and think about health separately from their social life, daily routines, and the growing technologic infrastructure that supports these activities.

Opportunities for developing evidence about interventions that work and for informing enabling policies exist, for example, in the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). CMMI and PCORI are in a position to fund demonstrations with the specific goals of coordinating all programs, interventions, and outreach efforts that are targeted at the patient and engaging a patient in a single, cohesive self-management plan. It would be similarly valuable in funding research that examines “translational” barriers to applying the sciences of health literacy, behavior change, and behavioral economics in real-world interventions.

Policy Implications

What policy directions can help us to shift to health partnerships between the care team and patients and a health system that attracts and supports engagement? We need to craft our payment policies to foster a strong foundation of primary care to provide the kind of care that people value. Primary care and the professionals who provide it should be more equitably valued and more adequately compensated. Primary care has enormous potential to enhance engagement and to improve health outcomes, experience, and costs, but payment must be sufficient to support key elements of care that are essential to engagement, namely,

- Formation of trusted relationships—the starting point for partnership, engagement, and activation.

- Shared care planning and decision making that are not isolated activities but an evolving process that extends to end-of-life care when appropriate.

- Adequate clinician time and a team infrastructure for effective coordination and communication during and outside clinical visits.

- Recognition of cultural and sociodemographic factors that influence health and health equity.

- Culturally and linguistically appropriate resources that help patients to engage in their health care.

It is equally important to rethink the payment incentives that we create for patients through the design of insurance benefits and to remove financial barriers, such as out-of-pocket costs that deter patients from following recommendations, getting needed care, or pursuing healthier behaviors.

With changes in payment, we need to change the measurement system. Measurement and the information that it generates should be useful to and usable by patients and families. And patients, families, and their advocates should be integrated as respected partners in measure development and care evaluation. More measures should be developed to use patient-generated data, including patient experience of care and patient-reported outcomes, such as functional status, symptom burden, and quality of life. We need innovative strategies for seamless collection of patient-generated data and for provision of feedback as part of clinical work flow, and we need to make data available quickly so that they can be used to guide clinical improvement.

Changing the payment system will not automatically change how professionals interact with patients. We need to change medical education and training and the approach to licensure and certification of practicing clinicians and health care organizations. The process of valuing individuals, patients, and families as genuine partners in managing health care should begin with provider education and training, including continuing education.

Health Literacy: How Can We Confuse People Less?

A fundamental requirement for greater democratization of health care is greater health literacy among its beneficiaries and participants. Access to and comprehension of information follow the gradient of literacy skills, which are well documented in our nation. In recent studies, patient adoption of “portals” (explained below) was far slower among those who had worse literacy skills. Less literate older adults were less likely to own a smartphone, use the Internet to access health information, or communicate with health care providers via the Internet (Bailey et al., 2014). As much as 20% of our population will probably not contribute actively through personal engagement, because of literacy, language, physical, or mental limitations.

Applying Health Literacy Principles to Policy and Practice

Technologic advances and enthusiastic engagement by innovators and entrepreneurs are moving quickly to make democratization of health care a reality. Policies are needed to address three elements: inclusiveness (with attention to the 20% of the population unlikely to participate readily in data input), infrastructure for health democratization (for example, which data, services, cost and outcome metrics, and privacy protections to include), and user interface design (for easy access, navigation, and clarity).

Examples of Opportunities Related to Existing Legislation

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Nearly 36% of American adults have low health literacy. As detailed in an Institute of Medicine (IOM, now National Academy of Medicine) workshop summary (Health Literacy Implications for Health Care Reform), several ACA provisions directly acknowledge the need for greater attention to health literacy. As regulations are advanced, there are opportunities to ensure that all are able to access, navigate, and use health care in our country. The lens of health literacy can facilitate more effective communication with respect to specifics of coverage expansion (clarity in enrollment processes, network providers, costs and coverage, and use of health insurance), workforce training, and all patient information.

The Plain Writing Act of 2010. This act was a mandate for the federal government to use plain writing in documents issued to promote government communication with the public. Federal employees are to be trained in plain writing; senior officials are designated to oversee the act’s implementation and a process to gauge compliance. With this federal legislation as background, what are specific opportunities at state and local levels to ensure clarity and foster less confusion as to what all people need to understand and do for their health and health care?

Telehealth

Alternatives to Face-to-Face Encounters

As long as physicians have been treating patients, they have done so mainly in a “visit,” an in-person clinical encounter. Those encounters have generally occurred in a physician’s office or in an emergency department or other hospital setting (other than house calls, which are not common today). Since the 1990s, some physicians have been using e-mail for communication with their patients (often called e-visits), including communication about clinical issues (in addition to administrative issues), which can help patients to determine their need for a visit or to obviate a visit. The use of ordinary e-mail has been largely eclipsed by the use of secure messaging for many physicians and patients, usually through patient portals as promoted by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act. E-messaging is extremely efficient and desired by many patients, but it is still underused, and many patients say that their physicians do not respond readily. Secure messaging is asynchronous, so it is appropriate for issues that are nonurgent and not time-sensitive. But sometimes it is more efficient to communicate in real time. For a century, physicians and patients have used the telephone for conversation. Today, we have other real-time communication options for patients (IOM, 2012).

Real-time video communication, often called telemedicine, can ameliorate barriers of space and time spent in traveling to and from a health care professional. It can substitute for face-to-face consultation between providers and patients, and it can make professional collaboration among health care colleagues accessible. Telemedicine has been shown to improve patient access to medical care, especially in underserved areas, and to reduce costs to patients (Berman and Fenaughty, 2005; Hailey et al., 2002; Keely et al., 2013). However, the adoption of such technologies has been hampered by lack of reimbursement and by variations and restrictions in state-by-state licensure rules that have kept physicians from practicing medicine outside the states in which they are licensed.

Patient-Generated Health Data

For many years, physicians have asked patients to monitor their weight, blood pressure, blood sugar, and other characteristics and report them to their physicians or care managers. A burgeoning of connected devices now makes it possible to monitor those entities and more—including physical activity, sleep, and heart rhythm—and to transmit them over the Internet. It can be done actively or passively for patients who are quite ill. As reimbursement is shifting to reward improved outcomes at lower cost, some practices have been gathering patient-generated biometric data, usually as part of a system of managing care that involves nonphysician staff with physicians involved as needed. But patient-generated health data (PGHD) must go beyond biometric data and encompass patient-reported outcomes, values and preferences, pain scores, and adherence. For PGHD to be incorporated into practice, consideration must be given to

- Practice and patient workflow.

- Seamless integration into physician-practice tools, such as the electronic health record.

- Appropriate incentives.

- Accuracy of the devices.

Patient monitoring in combination with a human component (not as an isolated patient activity) has been shown to improve outcomes, reduce health care costs, and prevent unnecessary hospital admissions (Agboola et al., 2015; Jethwani et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2012).

Policy Issues

To facilitate widespread use of telemedicine, policies that are consistent among states must be developed, for example:

- Reimbursement for visits that is based on what was done, not on the channel used to conduct the visits.

- Reciprocal state professional-licensure approaches or a federal approach to telehealth licensure.

- Simplified, risk-based Food and Drug Administration approval of self-monitoring technologies.

- Increased funding for evaluation of non-visit-based care programs and technologies.

Shared Planning for Health

As in so many other aspects of modern life, transparent communication is helping to inform and rationalize health care. One example of such transparency is OpenNotes (Delbanco et al., 2012), a national initiative funded by several national philanthropies that urges health care providers to offer patients electronic access to the visit notes written by their doctors, nurses, and other clinicians. The goals are to improve communication and to engage patients (and their families) in care more actively. Although it was initiated in primary care, the OpenNotes movement has expanded to include medical and surgical specialties. Mental health professionals are increasingly offering patients their notes as part of the psychotherapeutic process, and fully transparent records are being shared in emergency rooms, on hospital wards, and in intensive-care units. Close to 10 million Americans have access to OpenNotes through patient portals. A growing number of studies indicate, for example, that inviting patients to read their notes may improve medication adherence, help patients to build more trusting and efficient partnerships with the care team for chronic-disease management, and improve patient safety (Bell et al., 2015a). As people become the primary stewards of their own journey through health and illness, striking opportunities for increasingly constructive patient engagement are on the horizon. For example, clinic notes, shaped largely by requirements for fee-for-service billing and, more recently, quality documentation, will need to evolve to play a greater role in informing patients about their health and treatment. And the Open Notes movement has demonstrated the potential to improve the accuracy of notes by inviting patients to examine, confirm, and correct physicians’ records (Bell et al., 2015a,b).

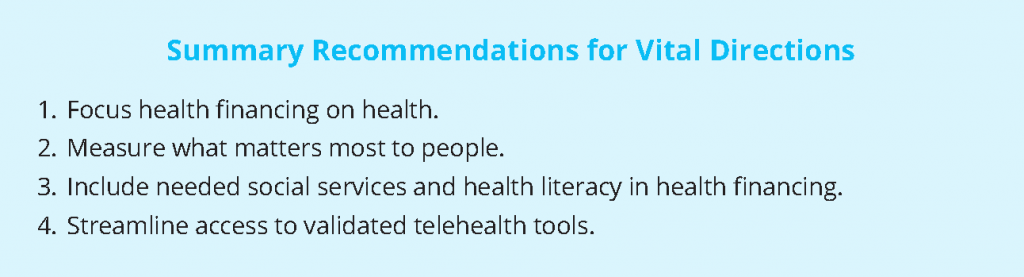

Recommended Vital Directions

- Focus health financing on health. Continue to advance payment-reform policies that provide incentives for providers’ comprehensive and long-term thinking about investment to promote health, including increased recognition of primary care as a central tenet of health reform to improve outcomes.

- Measure what matters most to people. Change the system of measuring quality to assess and reward performance on the basis of “measures that matter” to individuals, patients, and families. Fund development of specific measures that matter by the end of 2017, to be implemented in 2018 and affect payment in 2020.

- Include needed social services and health literacy in health financing. Experiment with greater use of Medicare, Medicaid, and private health-insurance funding for social and human services that demonstrate favorable effects on health outcomes or costs. Included in this should be health literacy services to ensure that information, processes, and delivery of health care in all settings align with the skills and abilities of all people.

- Streamline access to validated telehealth tools. Reconcile state-by-state regulatory barriers to telehealth and other online means of providing relevant, convenient, timely information about individuals’ health at times of need.

Conclusions

There is little disagreement on the substantial potential value of engaging patients and their family caregivers in managing health care. In fact, effective engagement of individuals and their families is key to succeeding under accountable-health models. Today, individual engagement happens in an uncoordinated way that does not take advantage of the scientific findings on how effective engagement must connect with the activities of everyday life. Individuals are facing increasing financial risk associated with health care decisions, but they lack tools for making informed decisions, namely patient-relevant data on options, outcomes, provider performance, and cost. Accelerating changes in health systems and technology support of patient engagement will require bold and deliberate restructuring of the payment system to reward value over volume. Despite widespread agreement on this general direction, wholesale behavior change throughout the health care enterprise awaits precise specifications of measures that appropriately assess whether services provided by health systems improve the health of individuals and communities. Public policies that unambiguously reward improving health will not only make the country’s priorities clear but will also motivate health systems to develop innovative solutions aligned with the national move toward a culture of health.

References

- Agboola, S., K. Jethwani, K. Khateeb, S. Moore, J. KveAgboola, S., K. Jethwani, K. Khateeb, S. Moore, and J. Kvedar. 2015. Heart failure remote monitoring: Evidence from the retrospective evaluation of a real-world remote monitoring program. Journal of Medical Internet Research 17(4):e101.https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4417

- Bailey, S. C., R. O’Conor, E. A. Bojarski, R. Mullen, R. E. Patzer, D. Vicencio, K. L. Jacobson, R. M. Parker, and M. S. Wolf. 2014. Literacy disparities in patient access and health-related use of Internet and mobile technologies. Health Expectations 18(6):3079-3087. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12294

- Bell, S. K., P. Folcarelli, M. Anselmo, B. Crotty, L. Flier, and J. Walker. 2015a. Connecting patients and clinicians: The anticipated effects of open notes on patient safety and quality of care. The Joint Commission

Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 41(8):378-384. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1553-7250(15)41049-9 - Bell, S. K. 2015b. Partnering with Patients for Safety: The OpenNotes Patient Reporting Tool. Poster presentation at the Annual Meeting, Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), Toronto, April 2015.

- Berman, M., and A. Fenaughty. 2005. Technology and managed care: Patient benefits of telemedicine in a rural health care network. Health Economics 14(6):559-573. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.952

- Delbanco, T., J. Walker, S. K. Bell, J. D. Darer, J. G. Elmore, N. Farag, H. J. Feldman, R. Mejilla, L. Ngo, J. D. Ralston, S. E. Ross, N. Trivedi, E. Vodicka, and S. G. Leveille. 2012. Inviting patients to read their doctors’ notes: A year’s experience and a look ahead. Annals of Internal Medicine 157(7):461-470. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00002

- Hailey, D., R. Roine, and A. Ohinmaa. 2002. Systematic review of evidence for the benefits of telemedicine. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 8(Suppl 1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1258/1357633021937604

- IOM. 2012. The role of telehealth in an evolving health care environment: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13466

- IOM. 2013a. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13444

- IOM. 2013b. Health literacy: Improving health, health systems, and health policy around the world: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18325

- Jethwani, K., E. Ling, M. Mohammed, K. Myint-U, A. Pelletier, and J. C. Kvedar. 2012. Diabetes connect: An evaluation of patient adoption and engagement in a web-based remote glucose monitoring program. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 6(6):1328-1336. https://doi.org/10.1177/193229681200600611

- Keely, E., C. Liddy C, and A. Afkham. 2013. Utilization, benefits, and impact of an e-consultation service across diverse specialties and primary care providers. Telemedicine and e-Health 19(10):733-738. https://doi.org/10.1089/ tmj.2013.0007

- Topol, E. 2015. The patient will see you now. New York: Basic Books.

- Squires, D., and C. Anderson. 2015, October. U.S. health care from a global perspective: Spending, use of services, prices, and health in 13 countries. The Commonwealth Fund. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019 (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Watson, A. J., K. Singh, K. Myint-U, R.W. Grant, K. Jethwani, E. Murachver, K. Harris, T.H. Lee, J.C. Kvedar. 2012. Evaluating a web-based self-management program for employees with hypertension and prehypertension: A randomized clinical trial. American Heart Journal 164(4):625-631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2012.06.013