The Communities That Care Coalition Model for Improving Community Health through Clinical–Community Partnerships: A Population Health Case Report

In rural western Massachusetts, a coalition with members from many sectors of the community has been working for more than a decade to support youth well-being and reduce youth substance abuse. In that time, youth drinking, cigarette smoking, and marijuana use have declined substantially, as have targeted risk factors underlying problem behaviors.

The Communities That Care Coalition serves a region encompassing 30 townships in Franklin County and the North Quabbin region, with a population of 87,000 distributed over 894 square miles. The region is economically depressed, with median household income 20 percent lower than the state median. The four largest towns (Greenfield, Athol, Montague, and Orange) are all low-income centers (median income 28, 30, 32, and 33 percent below the state level respectively), with many urban-style problems despite the rural surroundings (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010, 2013).

In 2002, representatives from the local hospital (Baystate Franklin Medical Center), local government, schools, social services, law enforcement, business, and faith-based organizations convened to address community concerns about substance abuse among the region’s young people. The community effort was spurred by the availability of substantial long-term funding from both the federal government and private sources given to two different agencies. (Notably, Partnership for Youth received a Drug-Free Communities (DFC) grant for $100,000 per year for 5 years, enabling the community to make a serious commitment to the process. Partnership for Youth subsequently won a second 5-year DFC grant, providing the foundation for a full decade of funding for coalition work.) The two agencies, Community Action of the Franklin, Hampshire, and North Quabbin Regions, and the Franklin Regional Council of Governments’ Partnership for Youth, chose to co-host the initiative, with dozens of collaborating partners unified in a region-wide approach.

The group adopted the Communities That Care (CTC) process to guide assessment, planning, and implementation of research-tested strategies. CTC is a community change process based on more than 2 decades of research by the University of Washington Social Development Research Group; in randomized trials, CTC has produced results both in achieving high-functioning coalitions and in reducing risky youth behaviors (Hawkins and Catalano, 2005). (The Communities That Care process grew out of the research of University of Washington’s J. David Hawkins and Richard F. Catalano on the Social Development Model.) A core multisectoral group participated in a series of five trainings and created a structure for the coalition. Five local school districts administered a survey to their 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students to assess health behaviors and underlying risk factors, and on that foundation the newly formed Communities That Care Coalition developed its first community action plan.

Description of the Initiative

Partnership for Youth and Community Action continue to serve as administrators, conveners, and advocates for the coalition. A 15-member cross-sector coordinating council meets quarterly to provide advice on coalition initiatives and make decisions about new directions and new funding opportunities. (Membership changes slightly over time, but sectors currently represented on the coordinating council are government, social service, the hospital, the faith community, business, schools, and other local coalitions.) The day-to-day work is implemented by the funding and strategies team—a subset of the coordinating council—and three to four action-oriented workgroups. The workgroup structure has evolved as the coalition has matured and embraced new initiatives and strategies, but the purpose of workgroups remains the same: to address priority risk factors and implement strategies laid out in the community action plan. (The current community plan is available at http://www.communitiesthatcarecoalition.org/community-action-plan (accessed January 7, 2016).)

The community action plan states the coalition’s mission, vision, and values; identifies priority risk factors and strategies to address those risk factors; and sets targets for outcome measures. The community action plan is a living document. It has been revised twice and is currently undergoing a third revision. With each revision, the coordinating council and workgroups review data and consider the effectiveness of current strategies, changes in the community that merit the coalition’s attention, and shifts in community resources. For example, one topic for discussion in the current revision is whether and how to address the perceived risk of substance use as marijuana use is normalized and opioid overdoses spike. A revision also offers the opportunity to discard strategies that are not showing evidence of effectiveness and to try something new.

The Communities That Care Coalition operates within a network of local sister coalitions. Three were formally mentored by the Communities That Care Coalition and focus on school districts or communities within the coalition’s geographic boundaries, deepening the prevention work within these communities. These coalitions and Communities That Care use a common language about risk factors and share an approach that attends to local data and research-based strategies. Three other local coalitions are substance-specific, with two addressing tobacco, and the third, the Opioid Task Force, addressing the region’s opioid crisis. Here the relationship is collaborative and complementary. Communities That Care in effect functions as a prevention arm of the Opioid Task Force, which also addresses treatment and recovery.

Coalition strategies include the following:

- Promote and sustain evidence-based universal prevention education in area schools. The coalition is currently supporting the schools in implementing the LifeSkills curriculum, by training teachers, providing evaluation support, and hosting a teacher group for peer sharing of advice. (The Botvin LifeSkills Training is listed in SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP) and is backed by solid research showing reductions and sustained outcomes in youth substance abuse and violence. https://www.lifeskillstraining.com/ (accessed January 7, 2016).) This effort is partly funded by the Baystate Franklin Medical Center and the Opioid Task Force.

- Provide alcoholic beverage trainings for staff of package stores, grocery and convenience stores, restaurants and bars, and organize compliance checks of licensed establishments. A Memorandum of Understanding signed with each town’s select board sets a schedule for compliance checks, a common penalty structure for violations, and collaborative arrangements for police to conduct the checks across town lines in smaller towns with only a few licensees. The coalition also conducts quarterly alcohol purchase surveys, which are similar to compliance checks, but without police involvement or penalties. They are intended to reinforce best practices of carding customers who appear to be under age 30 and to provide recognition and small rewards to vendors who card appropriately.

- Support evidence-based parent education, such as Guiding Good Choices and Nurturing Families (Guiding Good Choices is NREPP-listed with outcomes in youth substance use and delinquency and parenting behaviors and family interactions; Nurturing Families (an adaptation of the Nurturing Parenting Programs) is NREPP-listed with outcomes in parenting attitudes, knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors and family interaction) and promote family connection through mini-grants to local schools and community organizations. These mini-grants have supported diverse projects ranging from a book group for parents and children, a social marketing campaign to increase positive parenting norms, and a family dinner at a public housing complex to mark the opening of a new community center. Mini-grants serve the additional purpose of bringing new partners into coalition circles and raising awareness of the merits of using research-based approaches and tracking outcomes.

- Collaborate with the Opioid Task Force, Baystate Franklin Medical Center, and the schools to increase the use of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) in the schools and in the hospital emergency room. (SBIRT is supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and has been shown to be effective in reducing risky substance use. See http://www.samhsa.gov/sbirt.) The coalition has disseminated information about the effectiveness of SBIRT in identifying, reducing, and preventing problematic substance use, and has connected school staff experienced in SBIRT with schools interested in adopting SBIRT.

- Work with the Opioid Task Force to educate the community about adolescent substance abuse and addiction, and to improve clinician prescribing practices with scope-of-pain trainings, a safe prescriber pledge, and the Massachusetts Prescription Monitoring Program.

A high profile series of articles in the Stanford Social Innovation Review coined the term “collective impact” and profiled the Communities That Care Coalition as a successful example, highlighting the following features:

- A common agenda, as laid out in the Community Action Plan;

- Shared measurement, with agreed-upon priority risk factors and targets for outcomes;

- Mutually reinforcing activities, with diverse organizations working to create change across the community;

- Continuous communication, with quarterly meetings of the coordinating council, monthly meetings of the workgroups, and semiannual meetings of the full coalition (with a usual attendance of about 70); and

- Backbone support from staff at the two agencies that cohost the coalition (Hanleybrown et al., 2012).

The coalition, which uses the slogan “Prevention works. It’s working Here,” takes pride in its five key characteristics: collaborative, deploying evidence-based strategies, guided by local data, maintaining a positive perspective, and effective.

Results

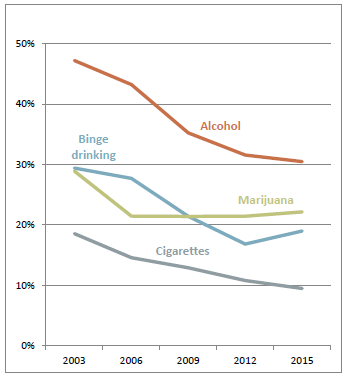

The evidence suggests that prevention is working in Franklin County. In the 12 years between the coalition’s first and most recent measurement of youth substance use, current alcohol use and binge drinking have dropped by 35 percent, cigarette smoking by 49 percent, and marijuana use by 23 percent. (Franklin County-North Quabbin Prevention Needs Assessment Survey, 2003-2015. The figures cited are based on combined prevalence of use by 8th, 10th, and 12th graders, weighted by grade to reflect actual enrollments. “Current” means any use of alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana within the 30 days preceding the survey. The binge drinking question asks whether the respondent has binged within the past 2 weeks.) See Figure 1. This is in part due to secular trends; declines in youth substance use have been observed in the state as a whole and across the nation during this time period. But declines in most local measures of use have outpaced those seen at state and national levels, suggesting that the coalition’s work may have contributed to the change. Although average age of first use for all teens for all substances has risen, (Exceptions to the rule that local changes compare favorably to the state are in current cigarette and marijuana use by 12th graders, which rebounded in the coalition’s latest survey. The coalition is taking steps to reverse that trend. In 2015, several Franklin County towns adopted regulations setting the legal purchase age for tobacco products at 21, with the expectation of reduced access to high school-aged students. The coalition will be monitoring the effects of this change. The coalition is planning efforts in education and advocacy as it anticipates the legalization of recreational use of marijuana in the near future.) the declines are most striking for younger teens: 8th-grade current alcohol use has fallen from 30 percent to 11 percent, and current marijuana use has dropped from 18 percent to 5 percent.

FIGURE 1 | Trends in recent substance use, 2003-2015.

NOTE: Franklin County/North Quabbin Prevention Needs Assessment Survey, combined results for 8th, 10th, and 12th graders, weighted by grade to reflect enrollments. Results are shown for the five school districts that have participated in the survey every year since 2003. Each year, n ranges from 1,000 to 1,350.

Although this is very welcome news, this information alone is not enough to conclude that the coalition’s efforts are successful. According to the logic of the coalition’s work, the coalition implements strategies to address risk factors that in turn influence youth behaviors. So no less encouraging than the declining substance use rates are reductions in the prevalence of risk factors. The coalition’s priority risk factors all fell over the 2003–2015 period (“Laws and Norms Favorable to Substance Use” and “Parent Attitudes Favorable to Substance Use” by 17 percent and “Poor Family Management” by 26 percent). Of the 20 interrelated risk factors measured, only one increased in prevalence: “Perceived Risk of Substance Use,” and that rise is due to changing attitudes about marijuana in the wake of decriminalization of possession and legalization of medical use. Over time, local youth have become, on average, subject to fewer risk factors. See Figure 2. The decline in substance use—and in antisocial behaviors—makes sense in light of the reduction in risk. (The Prevention Needs Assessment collects data on eight antisocial behaviors, and all decreased in prevalence from 2003 to 2015 so that they are now on a par with the national norm. For example, attacking someone with intent to harm within the past year fell from 17 percent to 6 percent, and selling illegal drugs within the past year fell from 12 percent to 7 percent.)

FIGURE 2 | Reduction in total number of risk factors per student, 2003-2015.

NOTE: Franklin County/North Quabbin Prevention Needs Assessment Survey, combined results for 8th, 10th, and 12th graders, weighted by grade to reflect enrollments. Results are shown for those students for whom all 20 risk factors were calculated in the five school districts that have participated in the survey every year since 2003. Each year, n ranges from 750 to 1,100.

Discussion

Use of Data

The data cited above come from the prevention needs assessment, a youth health survey designed to accompany the Communities That Care process, and these are the core data used to evaluate the coalition’s work. The coalition collaborates with nine area school districts to administer an annual youth health survey to all 8th, 10th, and 12th graders, cycling through three different survey instruments: the Prevention Needs Assessment, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, and a custom survey designed by the Regional School Health Task Force, a coalition workgroup with representation from each of the nine districts. (The Background section of this paper stated that five districts participated in the coalition’s first survey. In 2006 and 2007, the region’s remaining four districts joined the process.) Each survey fills a data need: the Prevention Needs Assessment goes “deep” with its exploration of risk factors; the Youth Risk Behavior Survey goes “wide” by covering a broad range of health behaviors; and the custom survey provides a check on issues of current local interest.

These survey data, supplemented by archival data from the schools, the hospital, law enforcement, and other sources, provided the foundation for the coalition’s original selection of priority risk factors and strategies. These data are used each year to evaluate the coalition’s work and report on progress, and they are updated and revisited with each revision of the community action plan. Considerations in selecting priority risk factors include the comparison of local prevalence to national prevalence, trends in local data that suggest new issues of concern, the correlation between the risk factor and targeted outcomes (in local data and national research), the availability of strategies to effectively address the risk factor, and the coherence with ongoing local initiatives.

The data are used not just by the coalition as a whole but by the individual organizations involved in the coalition and by the community at large. Survey data for the region are released each year with some public fanfare and posted on the coalition website. District-level data are provided to the schools for their use in planning, grant writing, and communicating with their constituencies, and requests for district-level data are referred directly to the schools. The coalition fills requests for data from community organizations and invites agencies to suggest questions for inclusion in the survey to track issues or populations of concern to them, such as foster children, or children with incarcerated parents. The press calls on the coalition for data as issues come into the public eye.

Barriers

The “backbone” staffing support to maintain the coalition’s functioning is funded through grants, and the importance of this role is not always appreciated by funders. The coalition has gone through a belt-tightening period of operating without funding explicitly supporting the backbone function, and some activities, such as the revision of the community action plan, had to be postponed. That period ended this year when the Baystate Franklin Medical Center Community Benefits Advisory Council stepped up with a generous 3-year grant that includes funding for backbone support.

The rural character of the region poses challenges. It requires the coalition to work with 30 independent townships and 9 separate school districts, to convene meetings that require at least some members to drive across the county, to identify strategies that are viable in different settings, and to craft messages that resonate for a region-wide audience. However, because towns are small and scattered and it is clear that no single town can provide all the services its population requires, local leaders are accustomed to working together and pooling resources.

Collaboration is in the history of the region. Moreover, Communities That Care’s collaboration with the three community-specific coalitions helps bridge the gap between regionwide prevention work and strategies designed for individual communities or school districts.

Health Equity

Student survey data help the coalition to understand which groups of local youth are at heightened risk, and additional qualitative data collection from at-risk youth took place in the fall of 2015 as part of the community action plan revision. These data will help ensure that disadvantaged populations are taken into account in planning. Agencies active in the coalition provide services to high-risk groups, such as Community Action’s programs for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth and out-of-school youth seeking employment skills, Big Brothers Big Sisters’ mentoring programs for low-income youth, and Montague Catholic Social Ministry’s parenting programs for court-referred families and for Spanish-speaking newcomers to the community. The prominence of service organizations within the coalition ensures that the community compliments the coalition’s prevention work with interventions more specifically designed for higher-risk youth and families, as well as youth and families already experiencing difficulties.

Clinical Care – Public Health Collaboration

Baystate Franklin Medical Center has been a partner in the coalition and has been represented on the coalition’s coordinating council from the beginning. Its role in the early years primarily centered on participating in strategic planning, hosting coalition meetings, printing coalition materials, and endorsing coalition activities. The involvement of the hospital has grown in recent years, as it has expanded its community benefits program, established a Community Benefits Advisory Council, conducted a community health needs assessment, and moved towards becoming increasingly accountable for the health of the community. As mentioned above, the hospital awarded Communities That Care a grant to support critical “backbone” activities, and along with that grant it is providing technical assistance on process and outcome evaluation. Moreover, just as the hospital has had a voice in the coalition’s work, the coalition has influenced the hospital’s community benefits program. The coalition is represented on the Community Benefits Advisory Council and has helped shape criteria for hospital grant-funded projects in keeping with the coalition’s commitment to evidence-based programs. The hospital has included coalition data in its community health needs assessment, and the coalition has used the hospital’s needs assessment in its strategic planning.

The coalition’s involvement with clinicians has also grown as the coalition has cemented its partnership with the Opioid Task Force whose health care solutions subcommittee reaches out to all of the region’s prescribers. The hospital president co-chairs this subcommittee, has promoted the safe prescriber pledge among all doctors with hospital privileges, and has hosted a scope-of-pain training for all staff. Through its community benefits program, the hospital has funded a position to offer technical assistance to all local providers to disseminate the safe prescriber pledge and to improve and expand use of the Prescription Monitoring Program. The coalition also partners with the hospital’s Perinatal Support Coalition, which screens pregnant women for substance abuse issues, refers them to services, and offers support through a peer recovery coach program.

An additional link to the medical community has come with a new wellness project funded by the federal Prevention and Public Health Fund. In this project, the coalition collaborates with the Community Health Center of Franklin County to build bridges between clinicians and community resources, with an expanded role for community health workers and e-referrals to community programs for individuals with hypertension and diabetes.

The Communities That Care Coalition of Franklin County and the North Quabbin region provides an example of how a collaboration involving health care and community partners can successfully create measurable, positive changes in community health. This model is widely replicable, and resources for support are available: the Communities That Care process for organizing, planning, implementing, and evaluating community change; the federal Drug-Free Communities Support Program, which has funded more than 2,000 prevention coalitions across the nation since its inception in 1997; and training and technical assistance from Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (CADCA, 2016). (CADCA is supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration and provides training and technical support to DFC-funded coalitions and other prevention coalitions.) The potential for the model is demonstrated not only by the example of the coalition described here, but by evidence of success among other Drug-Free Communities grantees and among coalitions using the Communities That Care process. (National evaluations show significantly sharper declines in alcohol and marijuana use in DFC-funded communities than in non-DFC communities. Drug-Free Communities Support Program. 2013 National Evaluation Report. Prepared by ICF International, June 2013. CTC has demonstrated results in community randomized trials. See, for example, Hawkins et al., 2014.) All illustrate how collective action—harnessed, organized, and directed toward a common goal—can achieve change in complex social systems.

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- CADCA (Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America). 2016. CADCA. Available at: http://www.cadca.org (accessed January 7, 2016).

- Hanleybrown, F., J. Kania, and M. Kramer. 2012. Channeling change: Making collective impact work. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Available at: http://www.ssireview.org/blog/entry/channeling_change_making_collective_impact_work (accessed January 7, 2016).

- Hawkins, J. D., and R. F. Catalano. 2005. Investing in your community’s youth: An introduction to the Communities That Care system. Available at: http://www.communitiesthatcare.net/userfiles/files/Investing-in-Your-CommunityYouth.pdf (accessed January 7, 2016).

- Hawkins, J. D., S. Oesterle, E. C. Brown, R. D. Abbott, and R. F. Catalano. 2014. Youth problem behaviors 8 years after implementing the Communities That Care prevention system: A community-randomized trial. JAMA Pediatrics 168(2):122-129. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4009

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. 2010 census. Available at: http://www.census.gov/2010census/ (accessed January 7, 2016).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2013. American Community Survey (ACS). Available at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/ (accessed January 7, 2016).