Tailoring Complex-Care Management, Coordination, and Integration for High-Need, High-Cost Patients: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

Introduction

The increasingly complex health care needs of the US population require a new vision and a new paradigm for the organization, financing, and delivery of health care services. Some 5% of adults (12 million people) have three or more chronic conditions and a functional limitation that makes it hard for them to perform basic daily tasks, such as feeding themselves or talking on the phone (Hayes et al., 2016). This group, “high-need, high-cost” (HNHC) people, makes up our nation’s sickest and most complex patient population. HNHC adults are a heterogeneous population that consists of adults who are under 65 years old and disabled, those who have advanced illnesses, the frail elderly, and people who have multiple chronic conditions.

Those complex patients account for about half the nation’s health care spending (Cohen and Yu, 2012). HNHC patients are often people who, despite receiving substantial health care services, have critical health needs that are unmet. That population will often receive ineffective care, such as unnecessary hospitalizations. By giving high priority to the care of HNHC patients, we can target our resources where they are likely to yield the greatest value better outcomes at lower cost.

We have an unprecedented opportunity to increase value of health care by rethinking our approaches to serving HNHC patients. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) offers an array of incentives and tools for pilot-testing and refining alternative delivery and payment models, and many states and private payers have been experimenting with new approaches. Health systems have responded by developing new approaches to health care delivery and greater public health outreach. The shift toward value-based, population-oriented care encourages the multiple providers (in and outside the health care system) involved in a patient’s care to collaborate to provide appropriate, high-quality care and achieve better patient outcomes. Now we need to disseminate information about successful programs, modify payment and financing systems, create a health care system that is conducive to the spread and scale of promising innovations, and eliminate remaining barriers that have impeded the adoption of effective approaches to caring for the nation’s most clinically and socially disadvantaged patients.

This paper explores key issues, spending implications, and existing barriers to meeting the needs of HNHC patients. We suggest policy options for a new federal administration to improve complex care management, care coordination, and integration of services for that population. Given that the number of patients living with multiple chronic illnesses is likely to grow, finding ways to improve outcomes for this population while avoiding unnecessary or even harmful use of health care services should have high priority for the new president and new administration.

Overview of High-Need, High-Cost Patients

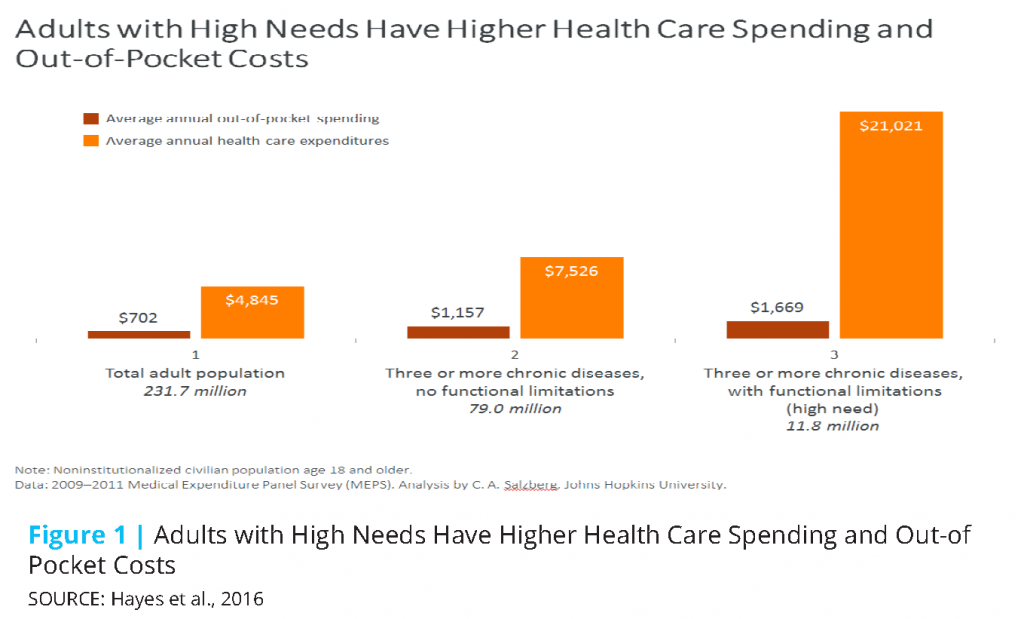

HNHC patients are people who have clinically complex medical and social needs, often with functional limitations and behavioral-health conditions, and who incur high health care spending or are likely to in the near future. The people in that population have varied medical, behavioral health, and social-service needs and service-use patterns. A recent analysis of the nationally representative 2009–2011 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey by Gerard Anderson, of Johns Hopkins University, showed that 94% of people whose annual total health care expenditures were in the top 10% of spending for all adults had three or more chronic conditions (Hayes et al., 2016). Some 34% of the total adult population, more than 79 million people, have three or more chronic conditions without any functional limitation, and their average annual health care spending ($7,526) is 55% higher than that of the total adult population ($4,845).

The additional burden of a functional impairment in the presence of multiple chronic conditions—that is, a long-term limitation in performing activities of daily living, such as bathing and eating, or instrumental activities of daily living, such as using the telephone or managing money without assistance—can substantially increase health care spending and use and the likelihood of receiving poor-quality care. Average annual health care expenditures are nearly three times as high for adults who have chronic conditions and functional impairments as for adults who have only chronic conditions ($21,021 vs $7,577) (Hayes et al., 2016) (see Figure 1). People who had multiple chronic conditions and functional limitations were more than twice as likely to visit the emergency department and three times as likely to experience an inpatient hospital stay as adults who had only multiple chronic conditions. They also were less able to remain in the workforce, so their annual incomes were much lower and they had greater difficulty in paying for medical services. They shouldered a greater cost burden with higher out-of-pocket costs ($1,169) than the US average ($702) (Hayes et al., 2016). Thus, functional impairments, both physical and cognitive, are important considerations when one is trying to identify and understand sick and frail patients whose health care is expensive.

The challenges facing HNHC patients extend beyond medical care into other related areas in which the relationship with their underlying illnesses can be complex. These patients often have substantial social needs and behavioral health concerns. Serious illnesses can lead to job losses, substantial economic hardships, and difficulties in navigating the health care system, including being unable to get to appointments. Inadequate social services—such as a lack of stable housing, a reliable food source, or basic transportation—can exacerbate health outcomes and increase health spending (Taylor et al., 2015). Similarly, adults who have behavioral-health conditions frequently experience fragmented care with no single coordinating provider, and this can result in higher spending and poorer outcomes (Druss and Walker, 2011). And people who are experiencing serious illness and approaching the end of life, primarily older people, often receive care that is unwanted, contrary to their preferences for care, and of highest cost (Brownlee and Berman, 2016). Addressing any one part of these complex relationships in isolation (for example, just the medical issues, just the social factors, or just the mental health problems) is probably inadequate. It is critical to take a holistic approach in which programs are tailored to address the whole array of issues for HNHC patients.

Health-system leaders, payers, and providers will need to look beyond the regular slate of medical services to coordinate, integrate, and effectively manage care for behavioral-health conditions and social-service needs for functional impairments to improve outcomes and lower spending.

Population Segmentation: A Critical First Step to Match Interventions to Patients’ Needs

HNHC patients make up a diverse population, including people who have major complex chronic conditions in multiple organ systems, the nonelderly disabled, frail elders, and children who have complex special health care needs. The heterogeneity of the population speaks to the implausibility of finding one delivery model or one program that meets the needs of all HNHC patients. Instead, payers and health systems may need to divide these patients into groups that have common needs so that specific complex care-management interventions can be targeted to the people who are most likely to benefit. Research by Ashish Jha, of the Harvard School of Public Health, is underway to derive a manageable number of groups among high-cost Medicare beneficiaries empirically on the basis of an analysis of multiple years of Medicare claims data.

Value-based delivery systems require a shift away from the disease-specific medical model, in which each clinician operates in his or her own specialty, to one that is more integrative and accepts multimorbidity and multidisciplinary care as the norm. In most health systems, care coordination occurs sequentially, and this may be adequate for uncomplicated cases. However, complex cases require seamless coordination with the spectrum of providers, patients, and caregivers reviewing and sharing information concurrently to inform and modify treatment plans simultaneously (Thompson, 2003). Many HNHC patients may move between groups and settings as their needs change, so flexibility and adaptability are essential for any intervention.

Denver Health, an integrated health system and the largest safety-net provider in Colorado, stratifies all patients according to risk by using a combination of risk prediction software, medication data, functional status, and clinical indicators to identify patients who may need the help of nurse care managers, patient navigators, or clinical pharmacists (Hughes et al., 2004). The highest-risk patients are divided into nine segments, for example, people who have catastrophic conditions that include long-term dependence on medical technology (such as dialysis machines or respirators) and patients whose conditions require continuing care (such as AIDS or heart-transplantation patients). Low-risk patients may receive text messages with reminders about appointments, but higher-need patients receive comprehensive follow-up care after appointments and substantial social and behavioral-health support (Johnson et al., 2015). For the highest-risk patients, Denver Health funded three high-intensity clinics with small patient panels, such as adults who have significant mental health diagnoses and recent multiple readmissions. Segmentation is not without its practical challenges. First, it is expensive to develop. Denver Health received a $19.8 million grant from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) in 2012 to support its risk-prediction development process. Second, there is an inherent tension between integration and specialization of services when patients are divided into groups, which could lead to increased fragmentation of care. More analysis is needed to assess the implications of segmentation and identify the best ways to ensure coordinated, patient-centered, and continuous care.

What Works? Lessons from the Literature on Promising Models for the High-Need, High-Cost Population

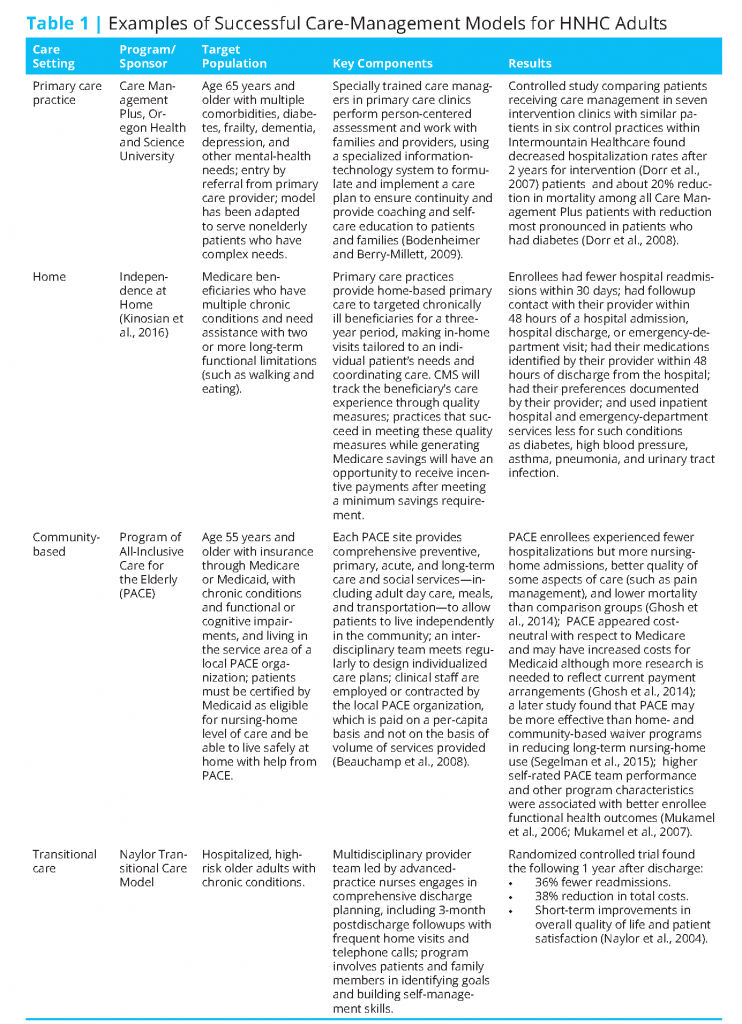

Improvement in the HNHC population has proved difficult to achieve in many instances; however, the evidence shows that a number of care-management models targeting HNHC patients have had favorable results in quality of care and quality of life and mixed results in their ability to reduce unnecessary hospital use or reduce costs of care (Boult et al., 2009; Brown et al., 2012; Hong et al., 2014b; Nelson, 2012). A 2015 review of the literature by Johns Hopkins University researchers identified 13 rigorous studies that reported health care use and spending outcomes for patients who had multiple chronic conditions. Of the 13, 12 reported a significant reduction in hospital use or cost; however, only 2 of the 12 showed significantly favorable results in all three domains of the triple aim: quality of care, patient experience, and use or cost of care (Bleich et al., 2015). There are important issues regarding the sustainability of these models. For example, only half the programs identified were still operating when they were contacted by Johns Hopkins researchers in 2015. To illustrate the variety of interventions that target HNHC patients and have been shown to work, Table 1 presents four examples of successful models. The four were selected because they have generated evidence of improved care, better patient experience, and lower use or cost of care and they show the variety of care settings in which such models can operate, including a primary care practice, the community setting, and a patient’s home.

An examination of the care-management models that had favorable outcomes reveals their common features. Common attributes include closely targeting patients who are most likely to benefit from the intervention, comprehensive assessment of patients’ risks and needs, specially trained care managers who facilitate coordination and communication between patient and care team, and effective interdisciplinary teamwork (Anderson et al., 2015; McCarthy et al., 2015). An important feature of innovative models is the ability to manage patients in multiple settings because patients are at high risk of moving from primary care to hospital to post-acute care site or nursing home. An analysis by Avalere in 2014 showed substantial return on investment in programs that actively managed Medicare patients’ transitions between hospital, skilled nursing facility, and home (Rodriguez et al., 2014).

Challenges to Spread and Scale

Despite evidence from a number of models that show spending reductions and increased efficiency, several barriers limit the widespread adoption of these programs. The most prominent obstacle is the misalignment of financial incentives. Few programs like accountable care organizations (ACOs) have implemented value-based physician compensation to align with value-based payment; capital and reorganization costs are often borne by the providers, but the savings accrue to the ACO or payer. The financial incentives do not always accrue to the program that undertakes the investment; for example, Medicare typically makes the investment necessary to keep HNHC patients out of nursing homes or long-term care facilities, but the savings accrue to Medicaid and thus are shared by federal and state governments.

Among nonfinancial barriers, professional uncertainty and lack of training and skill to take on new roles can impede the successful adoption of care management and the necessary accompanying culture change. Training in care coordination, for example, is a necessary addition to the academic curriculum. A lack of interoperability for electronic health record systems precludes integration and coordination throughout the care continuum. Finally, lack of rigorous evidence from multisite interventions—in both the public and private sectors—can make it difficult to determine the generalizability and sustainability of different models or program features in multiple contexts. A shared evaluation framework or common set of outcome measures could help to accelerate testing in both the private and public sectors, which is an important strategy for building a robust evidence base.

Recommended Vital Directions

The aging of the population, the shift toward value-based payment, the growth of alternative delivery systems, and the growth of managed care (both Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care) are prompting providers and payers to focus their attention on HNHC patients. In anticipation of the new federal administration, we outline a variety of promising policy options that could improve complex care management for people who are at risk of poor outcomes and unnecessary use of health care and high expenditures for it.

Promote Value-Based Payment

A critical strategy to improve care for HNHC patients is to continue to expand the prevalence and improve the effectiveness of value-based payment for risk-bearing organizations, such as ACOs, Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, and risk-based Medicaid managed-care plans. As mentioned above, HNHC patients are the heaviest users of services, and in a fee-for-service environment, there is little incentive for providers to collaborate to help patients who have clinically and socially complex needs. Furthermore, with fee-for-service payment, health systems or hospitals that are developing innovative approaches to help to keep patients healthy or avoid hospitalizations face substantial financial losses. In contrast, capitated payments to a group of providers, such as an ACO or MA plan, give providers an incentive to focus on quality of care and efficiency of services for their patient populations without being preoccupied with generating volume to increase revenue. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell has announced the goal of ensuring that 90% of Medicare payments be value based by 2018 (Burwell, 2015), and a new administration should continue that policy direction because it could have considerable favorable implications for HNHC patients.

Improve the Design and Implementation of Value-Based Payment

Despite the promise of value-based payment, much evaluation and fine-tuning of new payment approaches are needed to improve its implementation and in particular to understand the implications for patients who have clinically and socially complex needs. However, on the basis of experience with value-based payment thus far, a number of needs for improvement have already emerged. First, there needs to be greater alignment between value based payments to risk-bearing organizations and value-based payments to individual providers that are part of those organizations. A recent study found that most ACOs and risk-based plans continue to pay their individual clinicians on a fee-for-service basis, and this makes it difficult to translate the ethos of value-based payment to practicing clinicians (Bailit et al., 2015). If the individual providers or practice sites do not feel the shift toward accountability, population health, and value, the diffusion of promising practices or models of care will be slow. Medicare and Medicaid could work more closely with private provider organizations to achieve greater symmetry between organizational and provider payment approaches. It will also be crucial to make sure that the new incentives do not place such undue financial pressure on providers that they compromise care.

Second, value-based payments to providers must account for the different risks that HNHC patients bring to their care and appropriately pay the entities that accept the risks. Most risk-adjustment systems have not done an adequate job of that. Without appropriate risk adjustment, providers face natural pressure either to skimp on care for the sickest patients and the ones who have the most complex conditions or to avoid them entirely. Recently, concern has grown that current risk-adjustment formulas used by the federal authorities do not account adequately for patients’ physical, behavioral, and social service needs, which are factors that substantially affect the health of the nation’s sickest and poorest patients and the ones who have the most complex conditions (Barnett et al., 2015). Adapting risk-adjustment methods to capture the scope of those patients’ risk more accurately will be critical for effective implementation of value-based payment policies.

A third concern is the misalignment between investment and savings. The savings from many complex care management programs often benefit another payer, party, or system even if the group bearing the actual costs is part of a risk-sharing organization. For example, most providers in an ACO, Medicaid managed care plan, or Medicare Advantage network are expected to cover the upfront costs (such as staff training and adjustments of information technology) associated with the program, but savings accrue to the ACO or the plan (Hong et al., 2014a). Even if the savings are shared with the clinician, experience suggests that it can take 3 years for the programs to produce savings, and this lag might discourage providers from investing in the first place. Supplemental payments to providers to support transformational and capital expenditures could help to defray the cost and speed adoption. Alternatively, a partial capitated fee (such as a per-member, per-month supplement) to the site that offers the care management program could cover part of the investment during the transition to value-based compensation.

The discrepancy between payment and savings has serious consequences for patients who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. In particular, the incentives for managing transitions from a facility to home are not well aligned. Care-coordination or care transition programs that help to keep this population at home or in the community are often paid for by Medicare. However, the savings, which probably result from a reduction in long-term nursing-home days, accrue to Medicaid. An arrangement would have to be negotiated to figure out how Medicare and Medicaid could share in the savings that result from keeping dually eligible people at home or in community settings.

Increase Flexibility of Accountable Providers to Pay for Nonmedical Services

Another issue is the scope of covered clinical and social services. Unaddressed personal and social needs can increase health care use and costs. Conversely, home meal delivery, which is a low-cost and simple intervention, can reduce hospitalizations and delay nursing-home admissions and thus reduce health-care expenditures. In traditional Medicare, the critical component of care-management programs that is often associated with savings—the care coordinator (a social worker or care manager)—is not a covered service. Medicare Advantage does cover a few supplemental services, but the scope and duration are inadequate and disease specific. There is more extensive coverage of supplemental, nonmedical services for Medicaid beneficiaries than for Medicare beneficiaries, but a number of highly effective, low-cost, nonmedical health interventions are excluded. Examples include housing support and reimbursement for community health workers, who provide peer support in chronic disease self-management and in navigating the system. However, we should be careful not to “medicalize” social services so that everything becomes health care and becomes subject to its rules. Other countries spend considerably more on social services; this allows them to spend less on medical care and can improve outcomes (Bradley and Taylor, 2013).

Provide Intensive Technical Assistance to Providers Regarding Care for High-Need, High-Cost Patients

Once value-based payment incentives are in place to encourage providers to improve care for HNHC patients, health system leaders and clinicians will need technical assistance to design and implement effective programs. Fortunately, the literature provides some guidance. Substantial evidence shows that successful programs effectively target patients who will benefit from interventions. In light of the heterogeneity of the population, public and private insurers may need to adapt benefits, payments, and care models to specific needs of beneficiary groups. Segmenting the high-need population into groups and then targeting the most at-risk patients within the groups will facilitate more successful implementation. Segmentation can also allow for greater person-centered care by eliciting and tailoring care to patients’ preferences (Berman, 2012). For Medicare or dually enrolled beneficiaries,

functional impairment is an important program eligibility factor to consider because such limitations correlate highly with increases in use, cost, and fragmented care. In the Medicaid context, patients who have substance-abuse disorders or severe and persistent mental health issues substantially increase spending; this suggests potential eligibility for this group of the Medicaid population (Boyd, et. al., 2010).

Give High Priority to Health-Information Exchange

The most promising care-management models depend on health information technology for efficient screening and identification of patients for inclusion. Information technology is crucial for enabling patients, caregivers, and providers in different settings and sectors to share critical behavioral, social, and medical information about patients to improve management of their care. Policies to promote interoperability and exchange of information among providers in and outside the health system could have important implications for the adoption and evaluation of promising programs.

Continue Active Experimentation and Support the Spread and Scale of Evidence-Based Practices

A number of promising models have demonstrated improvements in patient outcomes and reductions in spending, but much of the evidence base draws on studies conducted in few locations, health care settings, or populations. Even when promising models are successfully evaluated, generate favorable mass media coverage, and generally achieve widespread acclaim, they do not necessarily develop a clear path to sustainability without continuing grant support. More could be done to enable the US health care system to sustain, spread, and scale innovative delivery models. If we cannot solve the related issues of sustainability and scale, we are at risk of repeatedly developing and reinventing small, innovative pilots that go nowhere. First, we need to achieve consensus on the criteria that should be met to declare a model “evidence based” or successful. As a first step toward that goal, the National Academy of Medicine released Vital Signs: Core Metrics for Health and Health Care Progress in April 2015; it recommended 15 common domains for assessing performance at every level of the health care system (IOM, 2015). Next, payers and delivery-system leaders need to understand how core metrics can be applied to improve care delivery and health outcomes. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review is developing new analytic tools to produce independent evidence on the effective and relative value of new technologies for families and society; these tools are designed to encourage public discussions about priorities in health care. Similar approaches could be used to assess effects on care-delivery models. Third, health care practitioners need more support to learn how to translate the successful features of evidence-based models. Toward this end, the ACA created the CMMI and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) to promote experimentation to improve care for HNHC patients. The next administration and Congress should continue support for CMMI and PCORI with directions to test the effectiveness of care approaches for HNHC patients and should continue to encourage private sector engagement.

Conclusion

Improving care for HNHC patients is a key lever to bring national health spending to a more sustainable level and accomplish many needed changes in our health care system. There is an opportunity for a new president and the next administration to build on promising models and implement policy changes to improve outcomes for HNHC patients. Our recommendations follow.

- Promote and improve the design of value-based payment.

- Increase flexibility of accountable providers to pay for nonmedical services.

- Provide intensive technical assistance to providers regarding care for HNHC patients.

- Give high priority to health information exchange.

- Continue active experimentation to accelerate the spread and scale of evidence-based practices.

The challenge before us is to apply what we know to improve the health of Americans; this would also contribute to the nation’s economy. With the policy opportunities outlined above, we believe that the new federal administration could improve the health and welfare of our nation’s HNHC patients considerably.

References

- Anderson, G. F., J. Ballreich, S. Bleich, C. Boyd, E. DuGoff, B. Leff, C. Salzburg, and J. Wolff. 2015. Attributes common to programs that successfully treat high-need, high-cost individuals. American Journal of Managed Care 21(11):e597-e600. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26735292/ (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Bailit, M. H., M. E. Burns, and M. B. Dyer. 2015. Implementing value-based physician compensation: Advice from early adopters. Health Financial Management 69(7):40-47. Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/med/26376508 (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Barnett, M. L., J. Hsu, and J. M. McWilliams. 2015. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Internal Medicine 175(11):1803-1812. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4660

- Beauchamp, J., V. Cheh, R. Schmitz, P. Kemper, and J. Hall. 2008. The effect of the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) on quality: Final report. Washington, DC: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/files/migrated-medicare-demonstration-x/evalpace-outcomeimpact.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Berman, A. 2012. Living life in my own way—and dying that way as well. Health Affairs 31(4):871-874. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1046

- Bleich, S. N., C. Sherrod, A. Chiang, C. Boyd, J. Wolff, E. DuGoff, C. Salzberg, K. Anderson, B. Leff, and G. Anderson. 2015. Systematic review of programs treating high-need and high-cost people with multiple chronic diseases or disabilities in the United States, 2008–2014. Preventing Chronic Disease 12(E197). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2015/15_0275.htm (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Bodenheimer, T., and R. Berry-Millett. 2009. Care management of patients with complex health care needs. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Available at: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2009/12/care-management-of-patients-with-complex-health-care-needs.html (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Boult, C., A. F. Green, L. B. Boult, J.T. Pacala, C. Snyder, and B. Leff. 2009. Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: Evidence for the Institute of Medicine’s “Retooling for an Aging America” report. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57(12):2328-2337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02571.x

- Boyd, C., B. Leff, C. Weiss, J. Wolff, R. Clark, and T. Richards. 2010. Clarifying multimorbidity to improve targeting and delivery of clinical services for Medicaid populations. Trenton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies. Available at: http://www.chcs.org/media/Clarifying_Multimorbidity_for_Medicaid_report-FINAL.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Bradley, E. H., and L. Taylor. 2013. The American health care paradox: Why spending more is getting us less. Philadelphia, PA: Public Affairs.

- Brown, R., D. Peikes, G. Peterson, J. Schore, and C.M. Razafindrakoto. 2012. Six features of Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration Programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Affairs 31(6):1156-1166. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0393

- Brownlee, S., and A. Berman. 2016. Defining value in healthcare resource utilization: Articulating the role of the patient. Washington, DC: AcademyHealth. Available at: https://www.academyhealth.org/publications/2016-04/defining-value-health-care-resource-utilization-articulating-role-patient (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Burwell, S. 2015. Setting value-based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve U.S. healthcare. New England Journal of Medicine 372:897-899. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1500445

- Cohen, S., and W. Yu. 2012. The concentration and persistence in the level of health expenditures over time: Estimates for the U.S. population, 2008–2009. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st354/stat354.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Dorr, D. A., A. B. Wilcox, S. Jones, L. Burns, S.M. Donnelly, and C.P. Brunker. 2007. Care management dosage. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22(6):736-741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0138-z

- Dorr, D. A., A. B. Wilcox, C. P. Brunker, R.E. Burdon, and S.M. Donnelly. 2008. The effect of technology-supported, multi-disease care management on the mortality and hospitalization of seniors. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 56(12):2195-2202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02005.x

- Druss, B. G.. and E. R. Walker. 2011. Mental disorders and medical comorbidity. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Available at: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/02/mental-disorders-and-medical-comorbidity.html (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Ghosh, A., C. Orfield, and R. Schmitz. 2014. Evaluating PACE: A review of the literature. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/evaluating-pace-review-literature (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Hayes, S., C. Salzberg, D. McCarthy, D.C. Radley, M.K. Abrams, T. Shah, and G.F. Anderson. 2016. High-need, high-cost patients: Who are they and how do they use health care? New York: The Commonwealth Fund. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2016/aug/high-need-high-cost-patients-who-are-they-and-how-do-they-use (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Hong, C., M. K. Abrams, and T.G. Ferris. 2014a. Toward increased adoption of complex care management. New England Journal of Medicine 371(6):491-493. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1401755

- Hong, C. S., A. L. Siegel, and T. G. Ferris. 2014b. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: What makes for a successful care management program? New York: The Commonwealth Fund. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2014/aug/caring-high-need-high-cost-patients-what-makes-successful-care (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Hughes, J. S., R. F. Averill, J. Eisenhandler, N.I Goldfield, J. Muldoon, J.M. Neff, and J.C. Gay. 2004. Clinical risk groups: A classification system for risk-adjusted capitated based payment and health care management. Medical Care 42(1):81-90. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000102367.93252.70

- Institute of Medicine. 2015. Vital Signs: Core Metrics for Health and Health Care Progress. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/19402.

- Johnson, T. L., D. Brewer, R. Estacio, T. Vlasimsky, M. J. Durfee, K. R. Thompson, R. M. Everhart, D. J. Rinehart, and H. Batal. 2015. Augmenting predictive modeling tools and clinical insights for care coordination program design and implementation. eGEMs 3(1):1-20. https://doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1181

- Kinosian, B., G. Taler, P. Bolin, D. Gilden, Independence at Home Learning Collaborative Writing Group. 2016. Projected savings and workforce transformation from converting Independence at Home to a Medicare benefit. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 64(8):1531-1536. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14176

- McCarthy, D., J. Ryan, and S. Klein. 2015. Models of care for high-need, high-cost patients: An evidence synthesis. New York: The Commonwealth Fund. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/oct/models-care-high-need-high-cost-patients-evidence-synthesis (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Mukamel, D. B., H. Temkin-Greener, R. Delavan, D.R. Peterson, D. Gross, S. Kunitz, and T.F. Williams. 2006. Team performance and risk-adjusted health outcomes in the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE). Gerontologist 46(2):227-237. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/46.2.227

- Mukamel, D. B., D. R. Peterson, H. Temkin-Greener, R. Delvan, D. Gross, S.J. Kunitz, and T.F. Williams. 2007. Program characteristics and enrollees’ outcomes in the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE). Milbank Quarterly 85(3):499-531. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00497.x

- Naylor, M. D., D. A. Brooten, R. L. Campbell, G. Maislin, K.M. McCauley, and J.S. Schwartz. 2004. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52(5):675-684. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x

- Nelson, L. 2012. Lessons from Medicare’s demonstration projects on disease management, care coordination, and value-based payment. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office. Available at: http://cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/WP2012-01_Nelson_Medicare_DMCC_Demonstrations.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Rodriguez, S., D. Munevar, C. Delaney, L. Yang, and A. Tumlinson. 2014. Effective management of high-risk Medicare populations. Washington, DC: Avalere. Available at: https://avalere-health-production.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/pdfs/1411505132_AH_WhitePaper_TSF.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Segelman, M., X. Cai, C. van Reenen, and H. TemkinGreener. 2015. Transitioning from community-based to institutional long-term care: Comparing 1915(c) waiver and PACE enrollees. The Gerontologist. Available at: http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2015/08/17/geront.gnv106.full (accessed August 31, 2016).

- Taylor, L. A., C. E. Coyle, C. Ndumele, E. Rogan, M. Canavan, L. Curry, and E.H. Bradley. 2015. Leveraging the social determinants of health: What works? Boston, MA: Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160217

- Thompson, J. D. 2003. Organizations in action: Social science bases of administrative theory. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.