“Systems-Integrated CME”: The Implementation and Outcomes Imperative for Continuing Medical Education in the Learning Health Care Enterprise

Introduction

Health care delivery has evolved from a variably connected collective of individually owned proprietorships and independent hospitals to an environment in which physicians increasingly contract with or are employed by health care enterprises. While continuing medical education (CME) that is focused on the dissemination and maintenance of medical knowledge and the development of skills plays a critical role in helping physicians keep up to date, the authors of this manuscript believe the structure and delivery of CME have not sufficiently evolved to be broadly viewed by health enterprise leaders as a strategic or integral asset to improving health care delivery. Therefore, an evolution and a reconceptualization of the structure and function of CME are necessary to enable collaboration between leaders and improvement experts in health care enterprises and CME. In this paper, the authors describe models that better reflect a more effective role of CME within learning health care delivery enterprises and the implications of such models for these enterprises and the CME profession.

Background: The Context of Health Care

“CME is not keeping up with other methods that address identified gaps, align with outcome objectives, and address medical cognition. Systems like ours are making significant intellectual and financial investments in these [other] methods.” — Stephen R. T. Evans, MD, executive vice president, medical affairs and chief medical officer, MedStar Health (personal communication)

The delivery of patient care services is increasingly based in health care enterprises. These entities include hospitals in relationships with consolidated systems or chains, investor-owned practices, managed care organizations, accountable care organizations, medical homes, retail clinics, community health centers, and urgent care and surgical centers, among others. Four decades ago, care was delivered primarily by independent hospitals, independent physician’s office practices, and specialty group practices and reimbursed in a predominantly fee-for-service payment model. In contrast, today’s physicians are increasingly employed or affiliated with health care enterprises through contractual relationships. A 2018 Health Affairs blog reported a near doubling of the percentage of primary care physicians and specialists in practices owned by hospitals or health systems [1]. A 2018 American Medical Association Physician Practice Benchmark Survey found that “2018 marked the first year in which there were fewer physician owners of their practices (45.9 percent) than employees (47.4 percent)” [2], a trend that has continued according to the 2020 survey [3]. A recent JAMA report noted that 355 physician practices, crossing multiple specialties and including 1,426 sites and 5,714 physicians, were acquired by private equity firms from 2013–2016; the number of acquisitions increased each year from 59 in 2013 to 136 in 2016 [4]. While the operational definitions of “private practice” and “physician employment” are not consistent in the literature, the direction and pace of practice-setting changes are clear.

Health care enterprises are increasingly focused on the “Triple Aim” of health care (improving population health, effective stewardship of health care resources, and improving the patient care experience) [5]. They are also increasingly focusing on the appropriateness of care and avoiding overuse. Overuse refers to the provision of medical care or services that offer little or no evidence of benefit to patients and are duplicative, potentially or outright harmful, or unnecessary [6]. According to a report of the Institute of Medicine (IOM; now the National Academy of Medicine) [7], unnecessary services comprise the single largest source of waste in US health care, amounting to roughly a third of health care expenditures. Misuse is defined as failure to execute clinical care plans and procedures properly [8], potentially resulting in needless delays in treatment or patient harm. Overuse and misuse also expose patients to unnecessary harm. Time and resources spent on the overuse of some medical services divert time and attention from other interventions, leading to underuse of appropriate resources (many immunizations, for example) in large segments of the population (particularly those in underserved areas) [9]. In addition to a plethora of data collected from processes and outcomes of care, health care enterprises are increasingly examining patient-reported outcome measures, defined as “any report of the status of a patient’s (or person’s) health condition, health behavior, or experience with health care that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else” [10]. Health care enterprises are also assessing patient experience of care using measures such as Press Ganey [11], Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems [12], and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems [13] surveys. Patient experience is a component of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Value-Based Purchasing Program [14]. Improved levels of patient engagement have been shown to correlate with improved health care outcomes [15,16].

CME can help physicians and health care enterprises achieve the Triple Aim and improve the patient experience. In this paper, the authors articulate a vision for a more strategic role for CME within health care enterprises. The authors, who have substantive experience in CME development, delivery, and evaluation (DWP, DAD) and CME governance (DWP, GLF) also describe frameworks that CME professionals and health care enterprise leaders can collaboratively use to achieve these goals.

The Reality and Potential of CME

Physician education begins with four years of undergraduate (medical school) training, followed by graduate medical education (residency and sometimes fellowship) that lasts from three to as many as ten years. In addition, CME offers “educational activities which serve to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professional performance and relationships that a physician uses to provide services for patients, the public, or the profession” [17,18].

The CME system recognizes that physicians should continue to learn over the ensuing decades of their careers. It assumes that physicians should be able to pursue their own learning interests based on their specialty and practice situation as part of professional self-regulation. The CME system developed gradually over the first part of the twentieth century, gained momentum after World War II, and became more formalized, including the development of systems of accreditation of continuing education providers, starting in the late 1960s [19,20]. Accreditation “attempts to confirm the quality and integrity of accredited CE [continuing education] by establishing criteria for the evaluation of the providers, assessing whether accredited providers meet and maintain minimum standards, and promoting CME provider self-assessment and improvement” [21]. While not all physician educational events or materials are accredited, those that are have demonstrated adherence to standards for planning, mitigation of bias, and delivery.

In its earliest stages, hospital rounds, conferences, meetings, and journals allowed physicians to keep abreast of advances in medical science. Since then, CME has advanced to include a wider array of modalities for educational delivery—e.g., videos, podcasts, self-assessment programs, simulation centers, point-of-care learning, interprofessional team training, and other online education, all of which have been even further accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, CME has evolved to include active learning strategies, incorporation of theory and evidence from the learning sciences, emphasis on educational activities based on data-defined gaps in care delivery, post-educational assessments of physician intent or commitment to change [22,23], and emphasizing outcomes of care in addition to changes in knowledge.

Fifteen years ago, the Conjoint Committee on Continuing Medical Education (CCCME) undertook a three-year initiative to “explore, agree on, and propose changes to the present CME system” [24]. The committee, composed of 14 major stakeholders in CME, conducted its work at the height of public and professional attention to the IOM’s seminal reports, “To Err Is Human” [25] and “Crossing the Quality Chasm” [26]. The CCCME report addressed aspects of licensure and board certification but did not explicitly mention the role of CME. Rather, it focused on the physician user and reporting and credit management aspects but failed to recognize the emerging changes in practice and the impact of those changes on CME. Hospitals and health care systems were only minimally represented on the committee.

Five years later, the IOM report “Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions” [27] identified flaws in the structure and scientific underpinnings of continuing health professions education. It called for increased emphasis on interprofessional education and offered the possibility of better alignment between health care enterprise needs and CME. This report painted a new vision for continuing professional development, suggesting that health care enterprises appoint “a chief learning officer who would design and oversee a system of interprofessional, team-based learning that focuses on the delivery of evidence-based health care” [28]. Since the report, there has been an increased emphasis on interprofessional continuing education, including pathways for organizational interprofessional education accreditation. There have also been examples in some academic medical centers or integrated systems like Kaiser Permanente, where CME has a defined role in organizational improvement. However, a lack of alignment or integrated working relationship between CME and the improvement apparatus in many health enterprises continues to exist, even in health care enterprises that have an accredited CME unit.

CME continues to face several challenges. Tailoring education to a local practice environment is difficult when relevant, actual practice data is unavailable or insufficiently granular. Physicians largely believe they can accurately assess their learning needs [28] despite evidence to the contrary [29,30]. As such, they frequently select their educational activities based on self-perceptions of need instead of being guided by objective performance data. Despite evidence on the limited ability to impact practice, passive, single-session, and largely didactic activities are still common. Assessing outcomes beyond provider satisfaction, pre/post assessments of knowledge, or commitment to change is time-consuming and may be logistically or methodologically challenging and is thus underutilized. Credits for participation in learning activities are still largely determined by counting hours of learning time, rather than credit being awarded based on measurement of practice process changes or outcomes. Perhaps for these reasons, leaders of health care enterprises commonly perceive that CME is somewhat peripheral to the practice of medicine and the delivery of evidence-based care. Insufficiently few health care enterprise leaders have embraced CME as a strategic asset or change agent to help them meet their improvement and “Triple Aim” goals.

CME has historically focused on dissemination and maintenance of physician knowledge (“what to do”) and development of skills (“how to do it”). This focus continues to play an important and necessary role in serving the profession of medicine by providing a means for physicians to update their medical knowledge, pursue their learning interests and needs, and meet licensing, credentialing, and board certification requirements. Statewide and national organizations (e.g., state and national medical societies, medical specialty societies) will continue to play important roles in CME, particularly for physicians in independent practice and for specialty-specific content knowledge, procedural skills, and some aspects of state and national health policy.

However, the importance of tailoring CME to the local practice context will increase, especially given the increasing prevalence of relationships between physicians and health care enterprises. The authors of this manuscript believe a broader conceptualization and focus on the structure, function, design, and delivery of CME is necessary to better improve the quality, cost, and experience of patient care. Adequate and current content knowledge is necessary for ongoing care improvement. Consistent with outcomes frameworks proposed by Miller [31], Kirkpatrick [32], and Moore [33], CME providers will need to prioritize facilitating sustained clinical behavior change in the local health care enterprise environment. Health care enterprise leaders will then need to facilitate explicit inclusion of CME into their change and improvement apparatus. Yet, a recent survey of 26 different individuals working in CME highlighted a continued prioritization of knowledge-based, single educational activities over facilitating practice change [34]. In the sections that follow, the authors illustrate the gaps in coordination and alignment between CME and the health care delivery enterprise. The authors discuss how concepts from three different models of translating evidence into practice can be adapted to facilitate better integration of CME and health enterprise goals and strategies. The authors then discuss the implications of these new directions for the training and job expectations of CME professionals and the application of new skills. Finally, the authors discuss the implications of these new directions for health enterprise leadership.

Integrating Health Care Delivery and CME

The following quotes (personal communications) from health care enterprise executive leaders exemplify the perceived lack of coordination and alignment between CME and the needs of their enterprises.

“I really like the idea of CME as a management tool that is integrated into and aligned with the strategic plan of the organization. Now our CME is a perk to fund the interest of the individual physician vs. being aligned with the strategy of the organization. A minority of the education has limited value to our organization.” — Douglas P. Cropper, MHA, President and CEO, Genesis Health System

“In the thirty-three years that I served as CEO and President of the 310-bed Chesapeake Regional Medical Center, we required CME for staff membership. It was never related to a clinical deficiency or to strategic planning. We used internal and external benchmarks for quality improvement but did not relate it to CME programming.” — Donald S. Buckley, MHA, PhD, President Emeritus, Chesapeake Regional Medical Center

“What is needed is a mechanism whereby CME programming can tangibly demonstrate its relevance and contribution to the strategic needs of the organization as it carries out its mission and serves the community.” — Thomas M. Priselac, MPH, President and CEO, Cedars-Sinai Health System

In order to frame the following section, the authors offer a vignette:

The physician director of the CME Department in a statewide health care system has been informed that her department is being eliminated because of system-wide budget cuts necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. While appealing the decision to the system president, she was asked to show how department-sponsored CME activities have improved patient care. She describes two activities over the last two years where CME outcomes have been associated with improvements in care quality. The system president agrees to restore the department budget for one additional year, with the expectation that the department work with system improvement leaders and tangibly demonstrate its value in improving the outcomes, costs, and patient experience of care.

Over the past twenty years, the CME community has made progress incorporating the science of learning into educational planning. While this is an important and necessary evolution, the conceptualization, organization, focus, and delivery of CME must continue to adapt for the field to meet its potential of contributing to sustained improvements in patient health. CME needs to attend to the dynamic changes in the relationship of physicians with continually evolving health care enterprises. Enterprise-based CME professionals need to demonstrate value by designing and delivering gap-specific, theory- and evidence-grounded educational activities tailored to the context, culture, and operational structure of their specific health care enterprises. In turn, health care enterprise leaders need to financially support and facilitate necessary collaborations for these efforts. The objective should be to collaborate more effectively within health care enterprises to achieve integration with the enterprise’s performance improvement plans. The challenges are to objectively demonstrate and document the value of CME from the quality, cost, and service frame of reference of enterprise leaders and provide enterprise leadership with adaptable frameworks for implementing its application.

Several implementation-science-related models offer frameworks for an integrated role of CME in health care enterprises. These models provide a basis for a broader, multistakeholder development and evaluation of CME’s contribution to improved health of patients and populations. Previous authors have described how educators can use constructs from quality improvement, complex adaptive systems, diffusion of innovations, stages of change, knowledge-to-action, and other models [35,36,37,38]. In the section that follows, the authors highlight three additional frameworks that can be used as CME and health systems enterprises become more aligned in addressing gaps in health care. A single tool might be used, or different elements of these tools could be “mixed and matched,” depending on the specific intervention and opportunities to align with enterprise operational units.

Strategies to Facilitate Better Integration of CME and the Health Enterprise

Redesigning CME Interventions

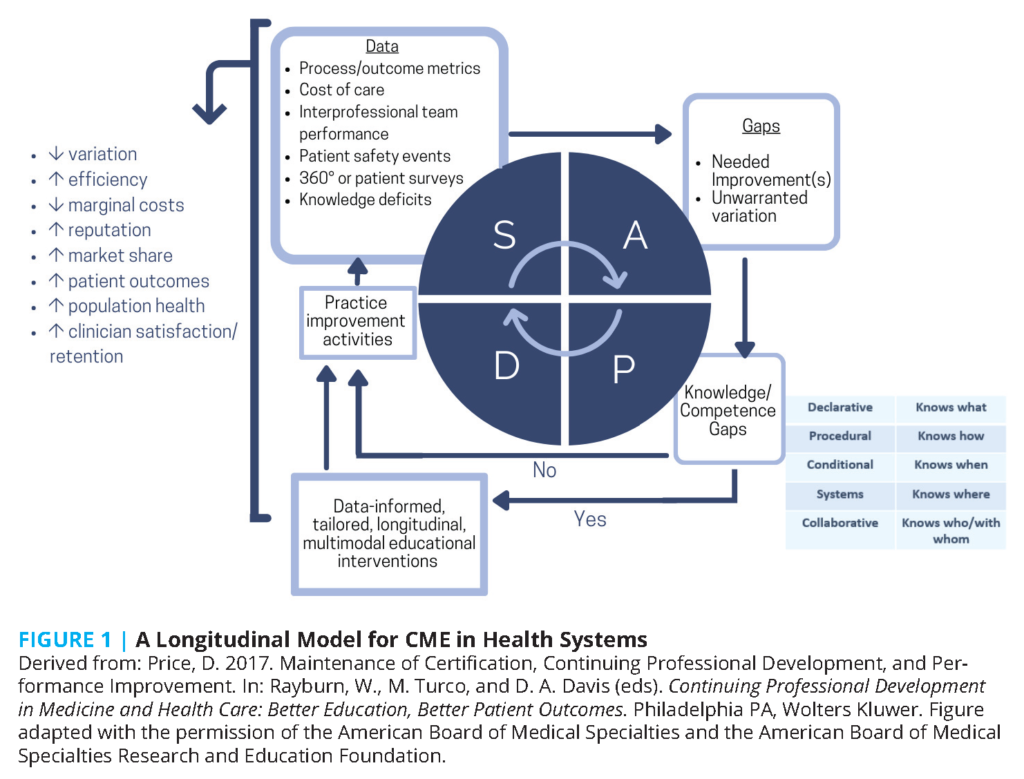

CME providers frame their work in terms of educational activities [39]. Many of these educational activities are developed and delivered as single-session topics or as collections of related but still individualized topics delivered at a point in time (e.g., conferences with concurrent sessions), over a period (e.g., tumor boards discussing different cancers), or in print or other enduring modalities. The authors observe that current, aggregated educational data are not specific enough to determine the frequency or degree to which activities review previous learnings and build off one another (scaffolding). CME could provide added value to health care and health care enterprises if efforts were delivered as educational interventions or initiatives driven by and supporting the work of organizational leaders, including those responsible for improvement in safety, quality, cost and patient experience. These CME efforts could be conceptualized as longitudinal efforts similar to repeated Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles [40]. Data from different sources (electronic health records, utilization data, insurance claims, public health and disease registries, medical literature, governmental quality reports, etc.) and individual and team performance data are analyzed to identify opportunities for improvement (“gaps” in the processes or outcomes of care). If analysis reveals deficits in individual or team knowledge or competence, then data-informed multimodal, longitudinal, interactive educational interventions are conducted. Education is followed by guided, longitudinal interventions allowing individuals and teams to apply and implement what they have learned in practice. If analysis does not reveal knowledge or competence gaps, educational activities step can be skipped, but guided implementation activities will still be necessary. Implementation activities are evaluated using the same data sources that identified the gap. The cycle continues, similar to iterative PDSA cycles, until unwarranted practice variation is reduced, and applicable “Triple Aim” outcomes are achieved. Involving physicians and other team members throughout the process could help streamline their work, engender engagement and buy-in with enterprise goals, and could contribute to enhanced physician/staff satisfaction (see Figure 1) [41]. Logic models graphically represent the shared relationships among the resources, activities, outputs, and outcomes or impacts for an initiative [42,43,44]. Theories of change explain how an intervention is expected to produce its desired results [45,46]. The authors recommend more frequently using theories of change and logic models to explain the role of CME in improvement interventions, guide the development of CME activities, and assess CME’s contribution to the outcomes improvement efforts.

Improving Descriptive Measures and Terms

Because CME is delivered in so many different contexts, the descriptive and evaluative lexicon used in CME is broad. While there are necessary trade-offs between flexibility (for context) and standardization (for comparison), the less well-defined CME descriptions and reporting terms (e.g., longitudinal, interactive) are, the greater the variability of their interpretation and use among CME providers and between CME providers and enterprise leadership. Common and specific definitions for terms, along with descriptions of the context in which they are delivered, would greatly enhance comparison among educational efforts and their relationship or contribution to outcomes of care.

Some metrics used in CME reporting (e.g., number of credits earned) appear straightforward, but problems occur in their interpretation, as credits earned are often based on attendee self-report of sessions attended, without measures of engagement. Other reporting terms are even less standardized and more subjective and are subject to high levels of inter-rater variability. For example, providers of accredited CME self-report whether their activities are designed to change practice. While several systematic reviews broadly outline the qualities of CME that are likely to result in practice change (longitudinal and sequenced sessions, reflective, interactive, feedback-based, multimodal, spaced, etc.) [47,48,49,50,51], to the knowledge of the authors, the degree to which this self-reported metric corresponds with actual use of these techniques is unclear. Additionally, CME providers likely differ in the criteria used to classify an activity as interactive and reflective. High-level reporting does not currently differentiate between the number or intensity of successful educational practices used.

There is not a simple solution to these definitional challenges. As a starting point, the authors suggest that CME providers specify how their activities address the improvement needs of the health care enterprise, meet design principles for effective CME, complement or reinforce other organizational improvement activities, and specifically define the measures they are using in activity evaluation. Subsequent qualitative analyses of these narrative comments could lead to development, testing, and refinement of more specific definitions of these terms for aggregate reporting.

Employing CME in Complex Adaptive Health Care Enterprises

Health care delivery enterprises are complex adaptive systems, with varied interrelationships between individuals and groups with differing perspectives and baseline knowledge and skills necessary for change [36,52,53]. A few desired improvements in health care organizations (e.g., introduction of an electronic health record alert to avoid antibiotic-warfarin drug-drug interactions) may be relatively simple or straightforward. Although implementation may take time (to reverse established behaviors), simple improvements generally have evidence-based and widely agreed-upon solutions, relatively few interdependencies, and little if any need for customization of implementation. On the other hand, some improvements (e.g., implementation of a laparoscopic instead of an open surgical procedure) may be more complicated. In these cases, the technical aspects of performing the procedure for the surgeon may be evidence-based and clear, but implementation may require changes in workflow or affect specialties or disciplines differently.

Many desired health care enterprise improvements (e.g., implementation of new treatment pathways) are complex. These may entail reconciling differences in guidelines or evidence interpretation; responding to differences between national guidelines and enterprise regulations (e.g., medication formulary issues); and coordination, communication, and collaboration between different medical specialties or between physicians and other health care professionals. These improvements require multilayered, multifaceted, tailored, and longitudinal approaches. The authors contend that enterprise-embedded CME is better positioned than CME offered to wide and diverse (e.g., national) audiences to help operationalize and tailor known evidence, guidelines, successful practices (the “what” and “the how”) into the context and culture of health care organizations and units (“how to do the how”).

CME and Learning Health Systems

“Knowing is not enough, we must do. Willing is not enough, we must apply.” — Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

The National Academy of Medicine defines a continuously learning health system as “one in which science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the care process, patients and families active participants in all elements, and new knowledge captured as an integral by-product of the care” [54]. Learning health systems have a leadership-instilled culture of learning. They use real-time access to data and evidence and partner with patients and families to improve care. They incent transparent efforts to continually improve and offer high-value care. In addition, learning health systems employ team training and skill building, systems analysis, and ongoing feedback for continuous learning and system improvement [7].

Individuals must be engaged, learn, and evolve for the health care enterprise to grow and improve [55,56,57,58]. The success of organizational learning is judged by observable behavioral change, not solely on cognitive changes [59]. By partnering with other enterprise personnel (e.g., human resources, process improvement, and data analysis experts), initiative- or intervention-based CME emphasizing individual and team-based knowledge and skill development could make significant contributions to the development of learning health care organizations. Several existing frameworks can be used to help organizational CME evolve for this purpose.

Frameworks for an Implementation Science Approach to CME in Learning Health Enterprises

Implementation science is the study of methods to promote the adoption and integration of evidence-based practices and policies into routine health care and public health settings to improve population health. Implementation science uses theories, models, principles, research designs, and methods derived from multiple disciplines and industries outside of medicine (e.g., organizational development, quality improvement, industrial engineering, business management, social science). Partnerships with key stakeholder groups (e.g., patients, providers, organizations, health systems, or communities) are critical in the application of implementation science [60,61]. Medical educators and health system leaders are increasingly turning to an implementation science lens to help frame and evaluate the impact of their work.

Conceptual frameworks are used to develop and evaluate multifaceted interventions. Building upon previous research (often outside of medicine), these frameworks describe and explain concepts, assumptions, expectations, key factors, constructs, and variables that may influence an outcome of interest [62]. The use of conceptual frameworks may increase the generalizability of findings. Below, the authors describe three frameworks derived from implementation science that can be used to conceptualize, design, implement, and evaluate CME integrated into health enterprise improvement.

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)

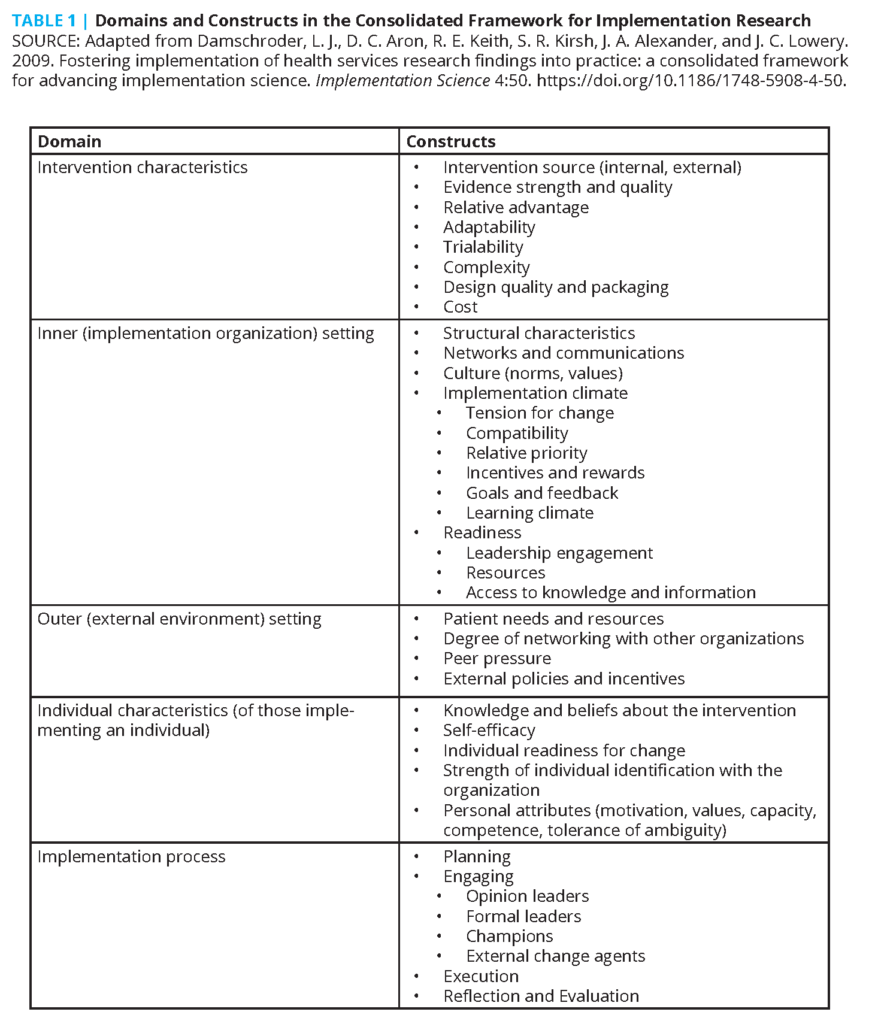

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [63] was developed to identify factors that might influence implementation and effectiveness of multifaceted interventions and guide rapid systematic assessment of such. It contains 39 constructs derived from several theories, including Rogers’s diffusion of innovation [64] and Prochaska’s transtheoretical stages of change [65] in five domains:

- intervention characteristics,

- features of the implementing organization,

- features of the external context or environment,

- characteristics of individuals involved in implementation, and

- the implementation process, which includes strategies or tactics that might influence implementation (see Table 1).

During intervention design, CFIR can help proactively anticipate facilitators and barriers (complexity, cost, inertia, competing priorities) to implementation. It can help tailor intervention structure and delivery across individuals, settings, and levels within an organization. CFIR can also identify barriers and facilitators to implementation in real-time rapid-cycle evaluation and suggest intervention improvement to stakeholders and leaders [66]. Stakeholders and subject experts within a health care enterprise could collaborate in different aspects of planning and delivery of educational and improvement interventions. For example, subject matter experts and informaticists could be responsible for gathering information on the strength of evidence. CME professionals could be responsible for the development of targeted, interactive, reflective, longitudinal activities for individuals and interprofessional teams that address knowledge, beliefs, skills, and self-efficacy. The CFIR model can help CME leaders new to or already engaging in accredited interprofessional continuing education more visibly align with the needs of health enterprises and leaders. Quality improvement and operational leaders could be responsible for implementation. Data analysts and embedded organizational researchers could be responsible for mixed methods evaluation of efforts.

Multilevel Organizational Learning Framework

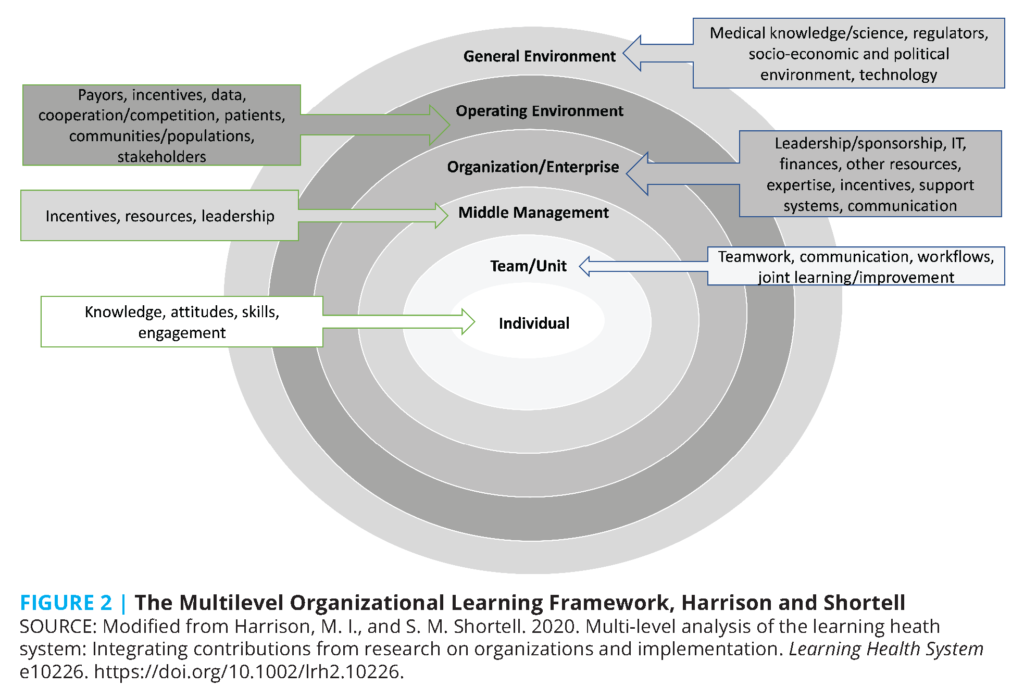

Patients are cared for by physicians, who are embedded within teams, themselves embedded in practice sites in different communities, which together comprise a specific health care system. Systems, in turn, interact with other systems and function in the larger health care delivery system and society at large. Harrison and Shortell used this socio-ecologic framework [67,68], CFIR, and an organizational change framework developed by Ferlie and Shortell [69] to develop a multilevel organizational learning framework [70] that can be used to analyze learning health systems at and between multiple levels (see Figure 2). This model illustrates the potential roles that CME can play in providing education as part of longitudinal, connected learning organization initiatives. Clinical knowledge and relevant science from the external environment can be tailored for organizational education in collaboration with others (e.g., treatment options from external trials and guidelines in the general environment could be tailored to be consistent with local formulary practices). As with the CFIR example, interactive, case-based education can be delivered to individuals and teams to affect attitudes and application of knowledge in discussion with peers. Educational efforts can be tailored to different groups, addressing team communication skills and workflows. Potential facilitators of and barriers to implementation can be identified and shared to inform subsequent improvement/implementation activities. Additional emerging gaps can be addressed with follow-up individual or team/unit education, based on their specific needs. Organizational data experts and researchers can help gather and analyze results from implementation activities and identify best practices, which could be part of follow-up educational activities. Joint learning sessions between individuals or teams, middle management, and leaders can help facilitate communication and joint problem solving across organizational layers while incentivizing continuing engagement and providing a sense of empowerment to individuals at the front lines.

RE-AIM

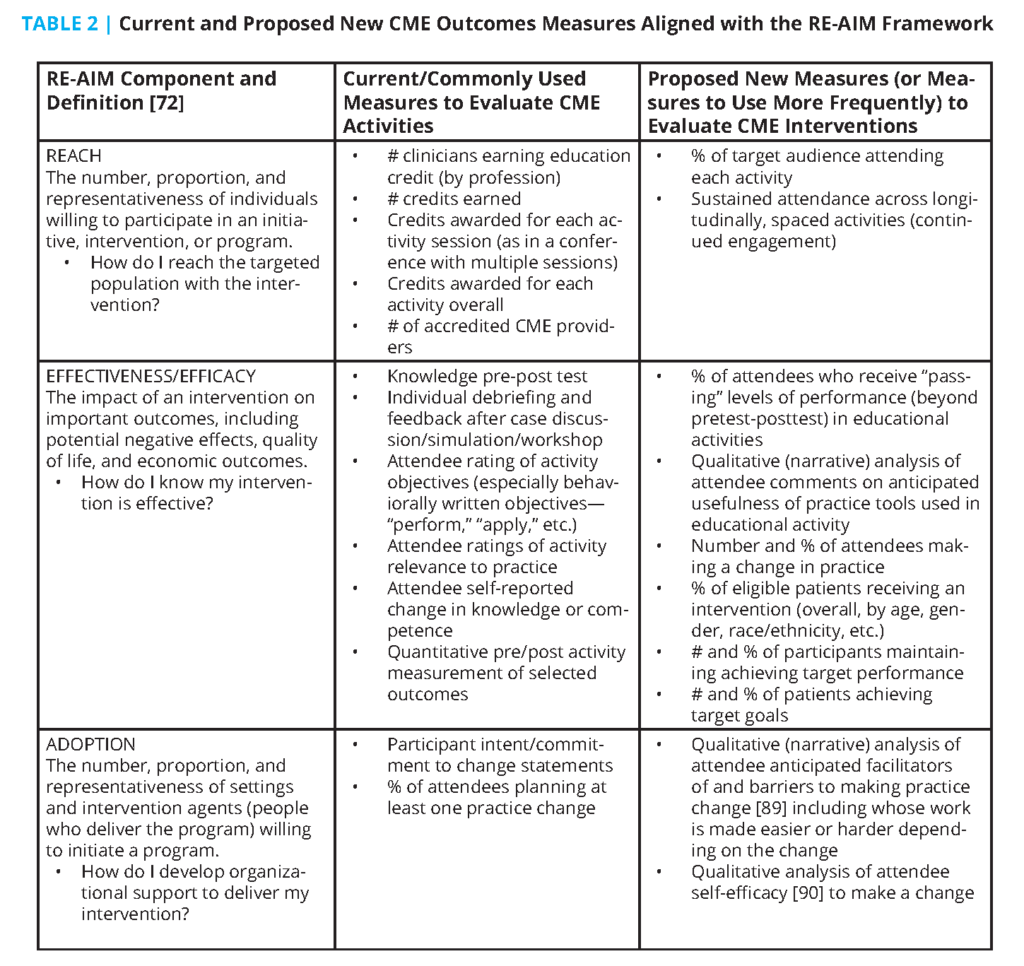

RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) [71,72] was developed as a framework for consistent reporting of research results. It has also been used to organize existing literature reviews on health promotion and disease management in different settings. The goal of RE-AIM is “to encourage program planners, evaluators, readers of journal articles, funders, and policy-makers to pay more attention to essential program elements including external validity that can improve the sustainable adoption and implementation of effective, generalizable, evidence-based interventions” [72]. It has been used to plan interventions to translate research into community and clinical settings [73] in topics including aging, cancer screening, dietary change, physical activity, medication adherence, chronic illness self-management, well-child care, eHealth, worksite health promotion, women’s health, smoking cessation, quality improvement, weight loss, and diabetes prevention.

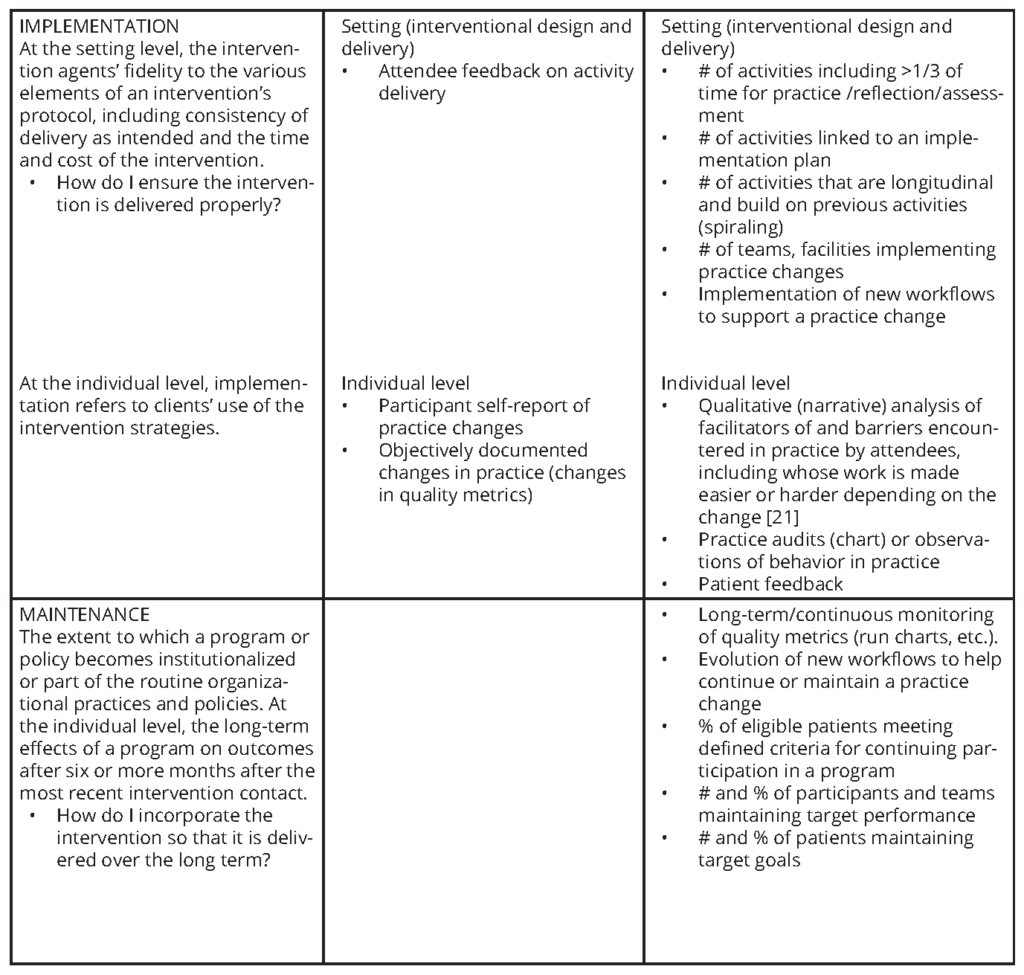

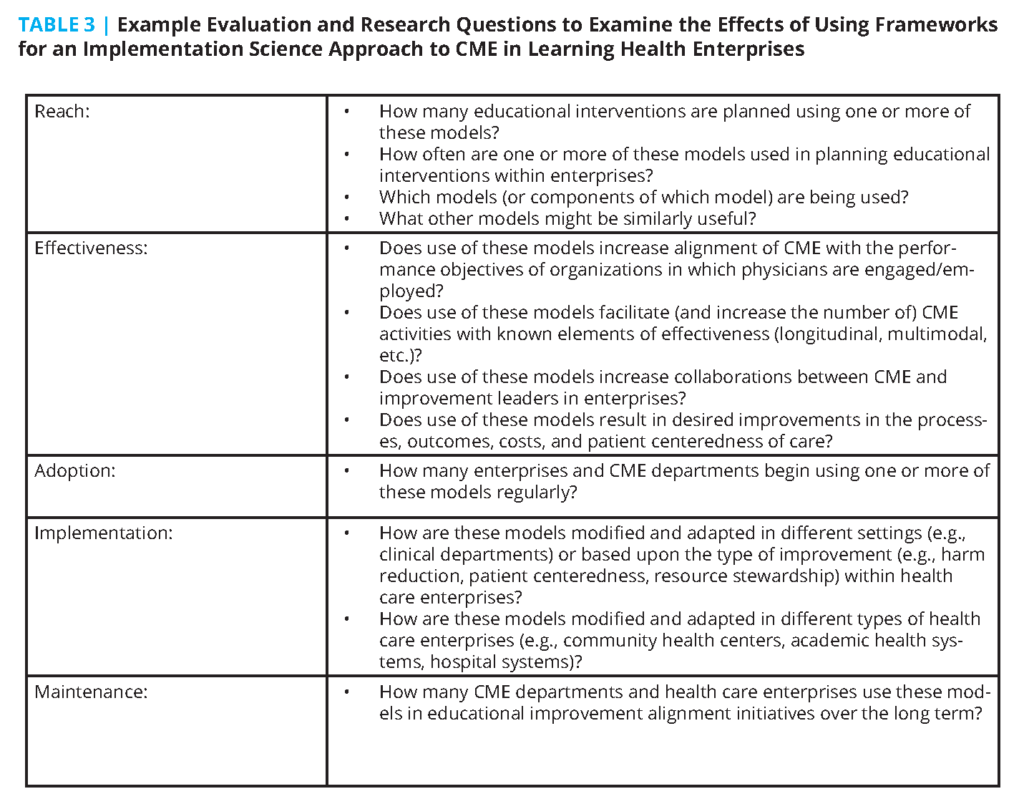

The RE-AIM framework can be used to guide and evaluate topically focused improvement activities in health care organizations [74]. Table 2 lists and defines the five components of the RE-AIM framework and shows current and proposed new metrics that health care enterprise leaders and CME professionals could use in RE-AIM-based initiatives.

From Attribution of Outcomes to CME to the Contribution of CME in Multifaceted System-Based Interventions

Case studies can be useful in understanding the effect of CME on practice change if they include a detailed description of CME design features, the context and organizational culture of a given intervention, and the use of qualitative and quantitative (mixed methods) evaluations that describe enabling factors and barriers to success. Mixed methods evaluation is particularly helpful for examining why and if an intervention did or did not succeed. Examples of success (“positive deviance” [75]) should also include key elements of the intervention necessary for successful replication in other contexts while noting features that can be adapted to help an intervention better fit in a different culture or context [76]. Descriptions of unsuccessful interventions outlining lessons learned can also be useful to decrease the chance that others (inside or outside a health care enterprise) try (exactly) the same thing and expect different results. The SQUIRE framework, widely used and accepted in facilitating reporting on health care quality and safety efforts [77], should be used in external publications whenever possible to facilitate comparisons of interventions, assist with generalizability, and expand the CME evidence base. In addition to helping health care systems leaders, this kind of reporting can help the CME community refine its measures and descriptors.

To examine higher levels of desired CME outcomes (performance, patient health, community health) [33], CME providers and health care enterprises should consider approaches such as contribution analysis that focus on the extent to which different entities contribute to an outcome by examining “credible causal claims (of effectiveness) under conditions of complexity” [78]. Schumacher et al. suggest that a combination of contribution analysis and physician attribution analysis could be of value [79]. A realistic and practical approach (“what works for whom under what circumstances”) [45] would benefit health professionals and help align CME with the needs of health care enterprise leaders by describing characteristics of effective CME development and delivery for internal replication and external dissemination. It will also help evolve scholarly work in CME and systems science and ultimately benefit patients and populations.

A Case Example

A statewide health system was working toward becoming an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Its goals included improving the patient experience; decreasing variations in care, particularly in high-cost conditions and emergency department overutilization; and improving identification and treatment of mental health conditions. The system president is also considering system transformation post-COVID-19, particularly continuing to offer telemedicine while recognizing the pent-up demand for in-person services.

Applying the Multilevel Organization Learning Framework, the physician CME director recognizes these organizational leadership priorities are influenced by the payment environment (ACO incentives) and more general environmental issues such as the use of telemedicine and COVID-19-related health care disruptions. She realizes that departments and organizational units are likely to view these priorities differently, based on specialty-specific knowledge, varying performance incentives, individual and team concerns, and patient pressures. Using CFIR, she asks for and receives system-wide communication from the system president, endorsing CME access to data and setting expectations for collaboration between departments, improvement leaders, and CME.

Members of the CME committee host a series of CFIR-based needs assessment discussions with clinical department leaders to identify areas where CME can assist departments in achieving one or more health system goals. The discussions include assessing department leadership readiness for change (inner setting), potential engagement of subject matter experts motivated to change (individual characteristics), and willingness of individuals within and across departments to serve as formal and informal leaders and champions for the implementation process. Members of the CME committee also look for opportunities to collaborate across departments and disciplines (inner setting).

As a result of this needs assessment, the CME committee decides to develop an initiative as a proof of concept—a longitudinal, spaced, multimodal educational intervention with individual feedback focused on the care of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Goals include decreasing variation in imaging utilization and opioid prescribing, decreasing emergency room utilization, increasing screening for mental health conditions, streamlining interdisciplinary collaboration to improve the care experience, and using telemedicine to supplement in-person care.

Leadership, subject matter expert, and champion input (CFIR inner setting, individual characteristics, implementation process) is solicited from anesthesiology, behavioral health, clinical pharmacy, emergency medicine, family medicine, internal medicine, neurology, neurosurgery, nursing, orthopedic surgery, physiatry, physical therapy, and radiology. Subject matter experts help identify relevant evidence-based literature. A series of educational activities, including an online review of applicable guidelines with a knowledge pre- and post-test, are developed. The Multilevel Organizational Learning Framework is used to target educational interventions at different levels of the enterprise. Individuals are then presented with relevant facility, team, and individual-level utilization, prescribing, and mental health screening data. CME leaders work with an interdisciplinary team and enterprise improvement experts to develop options and metric-driven aims for quality improvement for each goal. Small group education meetings are organized to allow individuals to talk with high-performing colleagues in their departments, provide peer-to-peer feedback in a safe environment, and commit to at least one practice change. Larger meetings are held to facilitate cross-department and interdisciplinary collaboration on improvement activities, identify potential barriers to implementation, and brainstorm methods of overcoming anticipated barriers. With individual and team end-user involvement, templates, reminders, and decision support tools are developed, tested, refined, and deployed in the enterprise electronic health record to reinforce learning and facilitate documentation and data capture. Each department is provided protected and compensated time to plan, test, and evaluate new workflows in a series of PDSA-based improvement cycles, with data, progress, and barriers discussed regularly at monthly meetings—ensuring that these changes do not inadvertently put an increased burden on physicians. Larger multispecialty, interdepartmental video conferences among local leadership occur quarterly to share best practices. A data infrastructure is developed to provide individuals and teams regular dashboards on their progress.

After one year, improvement is noted across all goals, along with further opportunities for improvement. A report is generated by clinical, improvement, and CME leadership based on the RE-AIM framework. The report includes Reach (departmental participation, number of individuals participating in educational and improvement sessions by specialty and discipline, and number of educational credits awarded), Effectiveness (pre-post-test changes in knowledge, longitudinal quality improvement data, and patient feedback on changes to the process), Adoption (comparison of intended to actual practice changes at the individual and team level, identification of system barriers to change and how they were addressed), and Implementation (number of individuals and teams achieving improvement, description of newly developed and implemented workflows, qualitative feedback on interdisciplinary and cross-department collaborations). The report is presented to the system president and the board of directors. One year later, maintenance is assessed by continuation of initial improvements, and sustainability of successful new workflows is monitored.

Implications for Strategic Alignment of CME with Health Care Delivery Enterprise Strategy

If CME is to realize its full potential, it is essential to develop a significantly expanded vision of its role, content, methods, integration, and measures of impact. The objective should be to position CME as an integral component of the managerial DNA of all health care delivery enterprises. Achieving this goal will require the development of a clearly defined and targeted impact strategy that is aligned with the operational needs and objectives of the health care enterprises with which most physicians are now affiliated.

To achieve this goal, CME professionals will need to provide tailored services in response to health care enterprise performance improvement plans and data, practice characteristics, and population health status. The resulting interventions should provide a bridge to operationalizing knowledge and skills into practice in the context and at the operating level of the enterprise. CME will need to collaborate with other leaders more consistently in the organization to identify and prioritize interventions based on timely and specific needs assessments. CME professionals will need to implement effective educational interventions (more than “one and done” activities) that address enterprise needs and contribute to outcome assessment aligned with the evaluation and management improvement plan of the organization. These CME interventions can help bring valuable outside perspectives to health care enterprises through identification and adaptation of national quality objectives and successful practices, particularly in areas of emerging evidence, like learnings from the COVID-19 pandemic. These steps are critical for alignment.

The New CME Professional

Beyond program administration, accreditation, and planning, the CME professional in this ideal future will be able to lead educational initiatives produced in the unique context and culture of the health care enterprises they serve. These initiatives should be based on adult learning theory and evidence of effectiveness and grounded in systems and implementation science. In addition, CME professionals will need knowledge in quality improvement, research methods, organization of medical practice, and professionalism [80]. In-depth coverage of this substantial body of knowledge would typically require a sizable time commitment. Individuals who end up providing CME in well-resourced organizations may not require expertise in all these areas, but the authors of this manuscript believe familiarity with key elements of these disciplines would facilitate collaboration with others who have these skills. Deeper knowledge in these areas may be needed by individuals who end up providing CME in smaller, less well-resourced health care enterprises.

Several existing master’s degree programs in medical or health professions education [81] include elements relevant to CME. While respected in academic circles, these programs have not yet achieved the recognition or status among health enterprise leaders as advanced training programs in public health or hospital and health care administration have. It may be possible to expand or reconfigure these programs to include the added training to successfully position CME professionals in health care delivery enterprises (particularly those outside of academic medical centers). However, it may be necessary to establish new master’s or fellowship training programs specifically designed to produce enough individuals with the knowledge and skills to provide effective educational interventions in a health enterprise environment. Such programs would be consistent with recommendations from the 2019 Future of Medical Education in Canada Report, which emphasizes the need for continuing professional development leaders to have knowledge and skills in systems-based practice and to have access to formal training opportunities including coaching, collaboration, and assessment [82].

In the shorter to intermediate term, “practice pathways” can help develop the skills of individuals working in health care enterprises. Shorter, more focused curricula in areas of individual inexperience, particularly in organizational and implementation science, could be developed for midcareer professionals. These should include opportunities to work with and learn from others with improvement, analytical, or evaluative expertise.

Regardless of the format, training programs should be rigorous and require more than self-study and multiple-choice tests. They should include structured curricula and multiple longitudinal, supervised experiences where trainees demonstrate successful application of knowledge in practice, receive feedback, and have opportunities to improve.

CME professionals must then apply this expanded knowledge and skill set in the activities they develop in service of health care enterprise. This will strengthen the rigor and alignment of educational activities with health care enterprise goals and will help demonstrate the value of CME professionals to the health care enterprise. While the primary intent is to strengthen alignment and collaborations between CME and health care enterprise improvement, the application of these skills could also be used to demonstrate compliance with several newer commendation criteria of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education [83].

Implications for Health Care Enterprise Leadership

Health care enterprises should expect that CME services demonstrably contribute to enterprise improvement. To do so, they must value, incentivize, and invest in CME services that are integrated into their culture and operations and responsive to their needs. Enterprise leaders should recognize and foster the professional development of individuals who can deploy the expanded CME skill set in addressing enterprise goals. Leaders should encourage, expect, and enable collaborations between CME services and others involved with enterprise improvement. Enterprise leaders should ensure that CME professionals have access to data to align, develop, and evaluate educational interventions supporting enterprise goals. Consistent with the goals of the National Academy of Medicine’s Evidence Mobilization Action Collaborative [84], enterprise leaders should also expect these collaborations to promote learning and improvement throughout the health care enterprise (including, but not limited to, physicians and other clinicians) by capturing learning, experience, successful practices, and data at the point of care.

Aligned with this vision, health care enterprises should consider developing compensated roles beyond the recruitment, hiring, onboarding, and regulatory requirements typically residing with senior human resources executives. These roles could include a “Chief Learning Officer” proposed in Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century [26], who would establish and lead a department with the capacity and competence to provide ongoing enterprise-focused educational interventions and evaluation in collaboration with quality, safety, applicable service delivery entities, and other members of the health care team. Alternatively, health care enterprises might contract with an independent outside provider of these services offered by, for example, academic health centers. Health enterprise leaders should also provide compensated, protected, nonbillable learning time to the physicians and other health care team members who engage in learning interventions that elicit individual perspectives and specifically address common individual and enterprise goals of improving patient care and outcomes.

Conclusion

Health system and patient needs provide an imperative to reimagine an expanded role of CME within learning health care enterprises. To meet these needs, CME requires integration with organizational and systems science in planning, delivering, and assessing the impact of education. In turn, health care enterprises need to use aligned, internal CME as a lever for enterprise improvement [85,86] rather than viewing it solely as a cost or revenue center or a means to help physicians meet licensing or credentialing requirements. Given the ongoing challenges of the cost of health care delivery (exacerbated by challenges imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic), the authors of this manuscript are concerned that health care enterprises will decrease support and protected learning time for educational and professional development services not aligned with their improvement plans. In contrast, the authors of this manuscript believe that health care enterprises will invest in educational services that are clearly aligned with and demonstrate substantial contribution to the objectives of their performance improvement plans. The effectiveness of implementation science frameworks in enabling CME-health enterprise alignment and collaboration should be evaluated. Table 3 provides example evaluation and research questions using the RE-AIM.

Finally, the authors of this manuscript believe collaborations between CME and those involved in health enterprise improvement, based on principles and frameworks from the learning, organizational, and implementation sciences, holds great promise for engaging physicians in addressing the patient care challenges faced by the health care enterprises in which they work. These collaborations can create bridges between micro- (physicians and other individuals), meso- (teams), and macro- (enterprise-wide) levels of health care enterprises [87,88], facilitating alignment toward common goals and enabling the development of learning health care enterprises. Combining “learning” and “doing” can help broaden the skills of CME and others involved in health care improvement and evaluation. The authors believe closer alignment, partnership, and integration between CME and health enterprise executive and improvement leaders is necessary to tackle complex problems and translate evidence (“the what” and “the how”) into health enterprise practice (“how to do the how”). Ultimately and most importantly, the authors believe this closer alignment, partnership, and integration holds great promise for improving patient and population care outcomes.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! Authors of #NAMPerspectives identify a number of potential frameworks that could be leveraged to approach redesigning CME in health care enterprises through an implementation science approach, including CFIR and RE-AIM. Read more: https://doi.org/10.31478/202110a #NAMPerspectives

Tweet this! Authors of #NAMPerspectives identify a number of potential frameworks that could be leveraged to approach redesigning CME in health care enterprises through an implementation science approach, including CFIR and RE-AIM. Read more: https://doi.org/10.31478/202110a #NAMPerspectives

![]() Tweet this! Continuing medical education has the possibility to be deployed to significantly improve care delivery in health care enterprises but requires evolution and reconceptualization. Read more in new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202110a #NAMPerspectives

Tweet this! Continuing medical education has the possibility to be deployed to significantly improve care delivery in health care enterprises but requires evolution and reconceptualization. Read more in new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202110a #NAMPerspectives

![]() Tweet this! Authors of a new #NAMPerspectives argue that “a broader conceptualization & focus on the structure, function, design, and delivery of CME is necessary to better improve the quality, cost, and experience of patient care.” Read more https://doi.org/10.31478/202110a #NAMPerspectives

Tweet this! Authors of a new #NAMPerspectives argue that “a broader conceptualization & focus on the structure, function, design, and delivery of CME is necessary to better improve the quality, cost, and experience of patient care.” Read more https://doi.org/10.31478/202110a #NAMPerspectives

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- Greaney, T. L., and R. M. Scheffler. 2020. The Proposed Vertical Merger Guidelines and Health Care: Little Guidance and Dubious Economics. Health Affairs Blog, April 17. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200413.223050/full/ (accessed November 3, 2020).

- Kane, C. K. 2019. Policy Research Perspectives: Updated Data on Physician Practice Arrangements: For the First Time, Fewer Physicians are Owners than Employees. American Medical Association. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-07/prp-fewer-owners-benchmark-survey-2018.pdf (accessed November 3, 2020).

- Kane, C. K. 2020. Policy Research Perspectives: Recent Changes in Physician Practice Arrangements: Private Practice Dropped to Less Than 50 percent of Physicians in 2020. American Medical Association. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-05/2020-prp-physician-practice-arrangements.pdf (accessed May 6, 2021).

- Zhu, J. M., L. M. Hua, and D. Polsky. 2020. Private Equity Acquisitions of Physician Medical Groups Across Specialties, 2013-2016. JAMA 323(7):663-665. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.2019.21844.

Berwick, D. M., T. W. Nolan, and J. Whittington. 2008. The Triple Aim: Care, Health, and Cost. Health Affairs 27(3);759-769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. - Choosing Wisely. n.d. Home. Available at: www.choosingwisely.org (accessed July 20, 2020).

- Institute of Medicine. 2013. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13444.

- Berwick, D. M. 2002. A User’s Manual for the IOM’s ‘Quality Chasm’ Report. Health Affairs 21(3):80-90. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.80.

- McGlynn, E. A., S. M. Asch, J. Adams, J. Keesey, J. Hicks, A. DeCristofaro, and E. A. Kerr. 2003. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 348(26):2635-2645. https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMsa022615.

- FDA Guidance for Industry. 2009. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf (accessed September 25, 2020).

- Presson, A. P., C. Zhang, A. M. Abtahi, J. Kean, M. Hung, and A. R. Tyser. 2017. Psychometric properties of the Press Ganey® Outpatient Medical Practice Survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 15(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0610-3.

- Solomon, L. S., R. D. Hays, A. M. Zaslavsky, L. Ding, and P. D. Cleary. 2005. Psychometric Properties of a Group-Level Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) Instrument. Medical Care 43(1):53. Available at: https://journals.lww.com/lww-medicalcare/Fulltext/2005/01000/Psychometric_Properties_of_a_Group_Level_Consumer.8.aspx (accessed August 30, 2021).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. n.d. HCAHPS: Patients’ Perspectives of Care Survey. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalHCAHPS (accessed November 4, 2020).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. n.d. What are the value-based programs? Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs (accessed November 4, 2020).

- Hibbard, J. H., and J. Greene. 2013. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Affairs (Millwood) 32(2):207-214. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061.

- Shortell, S. M., B. Y. Poon, P. P. Ramsay, H. P. Rodriguez, S. L. Ivey, T. Huber, J. Rich, and T. Summerfelt. 2017. A Multilevel Analysis of Patient Engagement and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Primary Care Practices of Accountable Care Organizations. Journal of General Internal Medicine 32(6):640-647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3980-z.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. n.d. CME Content: Definition and Examples. Available at: https://www.accme.org/accreditation-rules/policies/cme-content-definition-and-examples (accessed August 10, 2020).

- National Institutes of Health. n.d. What is CME Credit? Available at: https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-cme-credit (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Institute of Medicine. 2010. Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12704.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. n.d. History. Available at: https://accme.org/history (accessed November 4, 2020).

- Michigan State Medical Society Committee on CME Accreditation. 2009. Policy & Procedure Manual (A Guide to the Accreditation Process). Available at: https://www.msms.org/portals/0/documents/new_msms_accreditation_policy_and_procedure_manual.pdf (accessed August 30, 2021).

- Wakefield, J., C. P. Herbert, M. Maclure, C. Dormuth, J. M. Wright, J. Legare, P. Brett-MacLean, and J. Premi. 2003. Commitment to change statements can predict actual change in practice. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 23: 81-93. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.1340230205.

- Arnold-Rehring, S. M., J. F. Steiner, L. M. Reifler, K. A. Glenn, and M. F. Daley. 2021. Commitment to Change Statements and Actual Practice Change After a Continuing Medical Education intervention. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 41(2):145-152. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000340.

- Spivey, B. E. 2005. Continuing Medical Education in the United States: Why it needs reform and how we propose to accomplish it. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 25(3):134-143. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.20.

- Institute of Medicine. 2000. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9728.

- Institute of Medicine. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10027.

- Institute of Medicine. 2010. Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12704.

- Cook, D. A., M. J. Blachman, D. W. Price, C. P. West, R. A. Berger, and C. A. Wittich. 2017. Professional development perceptions and practices among US physicians: A cross-specialty national survey. Academic Medicine 92(9):1335-1345. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001624.

- Davis, D. A., P. E. Mazmanian, M. Fordis, R. Van Harrison, K. E. Thorpe, and L. Perrier. 2006. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: A systematic review. JAMA 288:1057-1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1094.

- Zell, E., and Z. Krizan. 2014. Do people have insight into their abilities? A metasynthesis. Perspectives on Psychological Science 9(2): 111-125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613518075.

- Miller, G. E. 1990. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine 65(9) (suppl):S63-S67. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045.

- Kirkpatrick, D. L. and J. D. Kirkpatrick. 2005. Transferring learning to behavior: using the four levels to improve performance. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Moore, D. E. Jr., J. S. Green, and H. A. Gallis. 2009. Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: Integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 29:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.20001.

- Ales, M. A., S. B. Rodrigues, C. D. Larrison, and R. B. Weldon. 2020. Aligning physician needs in learning and change with CPD community. Society for Academic CME Annual Meeting, Miami, FL, February 17.

- Price, D. 2005. Continuing medical education, quality improvement, and transfer of practice. Medical Teacher 27(3):259-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500046270.

- Shirazi, M., A. A. Zeinaloo, S. V. Parikh, M. Sadeghi, A. Taghva, M. Arbabi, A. Sabouri Kashani, F. Aleddini, K. Lonka, and R. Wahlstrom. 2008. Effects on readiness to change of an educational intervention on depressive disorders for general physicians in primary care based on a modified Prochaska model–a randomized controlled study. Family Practice 25(2):98-104. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmn008.

- Johnson, S. S., P. H. Castle, D. Van Marter, A. Roc, D. Neubauer, S. Auerbach, and E. DeAguiar. 2015. The Effect of Physician Continuing Medical Education on Patient-Reported Outcomes for Identifying and Optimally Managing Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 11(3):197-204. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4524.

- Sargeant, J., F. Borduas, A. Sales, D. Klein, B. Lynn, and H. Stenerson. 2011. CPD and KT: Models used and opportunities for synergy. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 31(3):167-173. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.20123.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. 2020. ACCME 2019 Data Report. Available at https://www.accme.org/2019-data-report (accessed September 20, 2020).

- Berwick, D. M. 1998. Developing and testing changes in delivery of care. Annals of Internal Medicine 128(8):651-6566. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00009.

- Price, D. 2017. Maintenance of Certification, Continuing Professional Development, and Performance Improvement. In: Rayburn, W., M. Turco, and D. A. Davis (eds). Continuing Professional Development in Medicine and Health Care: Better Education, Better Patient Outcomes. Philadelphia PA, Wolters Kluwer.

- Centers for Disease Control. n.d. Program Evaluation Framework Checklist for Step 2. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/eval/steps/step2/index.htm (accessed April 22, 2021).

- Funnell, S. C., and P. J. Rogers. 2011. Purposeful program theory: effective use of theories of change and logic models. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass.

- Van Melle, E. 2016. Using a Logic Model to Assist in the Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation of Educational Programs. Academic Medicine 91:1464. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001282.

- Pawson, R., and N. Tilley. 1997. Realistic evaluation. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Patton, M. Q. 2008. Utilization-focused evaluation. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Davis, D., M. A. O’Brien, N. Freemantle, F. M. Wolf, P. Mazmanian, and A. Taylor-Vaisey. 1999. Impact of formal continuing medical education: Do conferences, workshops rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA 282:867-874. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.9.867.

- O’Brien, M. A. T., N. Freemantle, A. D. Oxman, D. A. Davis, and J. Herrin. 2001. Continuing education meetings and workshops: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2)CD003030. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003030.

- Mazmanian, P. E., and D. A. Davis. 2002. Continuing medical education and the physician as learner: Guide to the evidence. JAMA 288:1057-1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.9.1057.

- Marinopoulos, S. S., T. Dorman, N. Ratanawongsa, L. M. Wilson, B. H. Ashar, J. L. Magaziner, R. G. Miller, P. A. Thomas, G. P. Prokopowicz, R. Qayyum, and E. B. Bass. 2007. Effectiveness of continuing medical education. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 149:1-69. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK38259/ (accessed August 30, 2021).

- Cervero, R. M., and J. K. Gaines. 2015. The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: An updated synthesis of systematic reviews. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 35(2):131-138. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21290.

- Snowden, D. J., and M. E. Boone. 2007. A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making. Harvard Business Review 85(11):68-76, 149. Available at: https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making (accessed August 30, 2021).

- Kannampallil, T. G., G. F. Schauer, T. Cohen, and V. L. Patel. 2011. Considering complexity in healthcare systems. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 44(6):943-947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2011.06.006.

- NAM Leadership Consortium: Collaboration for a Value & Science-Driven Health System. n.d. Home. Available at: https://nam.edu/programs/value-science-driven-health-care/ (accessed August 30, 2021).

- Lehesvirta, T. 2004. Learning processes in a work organization: From individual to collective and/or vice versa? Journal of Workplace Learning 16:92-100. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ803115 (accessed August 30, 2021).

- Ratnapalan, S. and E. Uleryk. 2014. Organizational Learning in Health Care Organizations. Systems 2: 24-33. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems2010024.

- Morain, S. R., N. E. Kass, and C. Grossman. 2016. What allows a health care system to become a learning health care system: Results from interviews with health systems leaders. Learning Health Systems 1:310015. https://doi.org/10.1002/lrh2.10015.

- Fiol, C. M., and M. A. Lyles. 1985. Organizational learning. Academy of Management Review 10(4):803-814. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4279103.

- Tsang, E. W. K. 1997. Organizational Learning and the Learning Organization: A Dichotomy Between Descriptive and Prescriptive Research. Human Relations 50:73-89. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679705000104.

- Eccles, M. P., and B. S. Mittman. 2006. Welcome to Implementation Science. Implementation Science 1:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1.

- Price, D. W., D. P. Wagner, N. K. Krane, S. C. Rougas, N. R. Lowitt, R. S. Offodile, L. J. Easdown, M. A. W. Andrews, C. M. Kodner, M. Lypson, and B. E. Barnes. 2015. What are the implications of implementation science for medical education? Medical Education Online 20:1, 27003. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v20.27003.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Damschroder, L. J., D. C. Aron, R. E. Keith, S. R. Kirsh, J. A. Alexander, and J. C. Lowery. 2009. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science 4:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

- Rogers, E. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th edition. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Prochaska, J. O., and W. F. Velicer. 1997.The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion 12:38-48. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38.

- Keith, R. E., J. C. Crosson, A. S. O’Malley, D. Cromp, and E. Fries Taylor. 2017. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: a rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implementation Science 12:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0550-7.

- Green, L., and M. Kreuter. 2005. Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- Tabak, R. G., E. C. Khoong, D. A. Chambers, and R. C. Brownson. 2012. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43(3):337-350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024.

- Ferlie, E. B., and S. M. Shortell. 2001. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Quarterly 79(2):281-315. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.00206.

- Harrison, M. I., and S. M. Shortell. 2020. Multi-level analysis of the learning heath system: Integrating contributions from research on organizations and implementation. Learning Health System e10226. https://doi.org/10.1002/lrh2.10226.

- Glasgow, R. E., T. M. Vogt, and S. M. Boles. 1999. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health 89(9):1322-1327. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322.

- RE-AIM. n.d. Home. Available at: http://www.re-aim.org/about/what-is-re-aim/ (accessed November 21, 2020.)

- Glasgow, R. E., and P. E. Estabrooks. 2018. Pragmatic applications of RE-AIM for health care initiatives in community and clinical settings. Preventing Chronic Disease 15:E02. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.170271.

- Brunisholz, K. D., J. Kim, L. A. Savitz, M. Hashibe, L. H. Gren, S. Hamilton, K. Huynh, and E. A. Joy. 2017. A Formative Evaluation of a Diabetes Prevention Program Using the RE-AIM Framework in a Learning Health Care System, Utah, 2013-2015. Preventing Chronic Disease 14:E58. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.160556.

- Bradley, E. H., L. A. Curry, S. Ramanadhan, L. Rowe, I. M. Nembhard, and H. M. Krumholz. 2009. Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implementation Science 4:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-25.

- Zimmerman, B., C. Lindburg, and P. Plsek. 1998. Edgeware: insights from complexity science for health care leaders. VHA Inc., Irving, Texas.

- Ogrinc, G., L. Davies, D. Goodman, P. B. Batalden, F. Davidoff, and D. Stevens. 2016. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Quality and Safety 25:986-992. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411.

- Van Melle, E., L. Gruppen, E. S. Holmboe, L. Flynn, I. Oandasan, J. R. Frank, and the International Competency-Based Medical Education Collaborators. 2017. Using Contribution Analysis to Evaluate Competency-Based Medical Education Programs: It’s All About Rigor in Thinking. Academic Medicine 92(6). https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001479.

- Schumacher, D. J., E. Dornoff, C. Carraccio, J. Busari, C. van der Vleuten, B. Kinnear, M. Kelleher, D. R. Sall, E. Warm, A. Martini, and E. Holmboe. 2020. The Power of Contribution and Attribution in Assessing Educational Outcomes for Individuals, Teams, and Programs. Academic Medicine 95(7):1014-1019. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003121.

- Davis, D. 2006. Continuing education, guideline implementation, and the emerging transdisciplinary field of knowledge translation. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 26 (1):5-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.46.

- Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (FAIMER). n.d. Home. Available at: https://www.faimer.org/resources/mastersmeded.html (accessed July 19, 2020).

- Campbell, C., and J. Sisler. n.d. Supporting Learning and Continuous Practice Improvement for Physicians in Canada: A New Way Forward. Summary Report of The Future Of Medical Education In Canada (FMEC) CPD Project. Available at: https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/profession/medical-education/fmec-cpd-final-report-feb-7-2019-e.pdf (accessed August 31, 2021).

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. n.d. Accreditation Criteria. Available at: https://www.accme.org/accreditation-rules/accreditation-criteria (accessed November 5, 2020.)

- National Academy of Medicine Leadership Consortium: Collaboration for a Value & Science Driven-Health System. n.d. Evidence Mobilization Action Collaborative. Available at: https://nam.edu/programs/value-science-driven-health-care/clinical-effectiveness-research/ (accessed November 6, 2020.)

- McMahon, G. T. 2017. The Leadership Case for Investing in Continuing Professional Development. Academic Medicine 92(8):1075-1077. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001619.

- Davis, D. A., and G. T. McMahon. 2018. Translating evidence into practice: Lessons for CPD. Medical Teacher 40(9):892-895. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1481285.

- Barbour, J. B. 2017. Micro/Meso/Macrolevels of analysis. The International Encyclopedia of Organizational Communication 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118955567.wbieoc140.

- Serpa, S., and C. M. Ferreira. 2019. Micro, Meso, and Macro Levels of Social Analysis. International Journal of Social Science Studies 7(3):120-124. https://doi.org/10.11114/ijsss.v7i3.4223.

- Price, D. W., E. K. Miller, A. Kulchuk-Rahm, N. E. Brace, and R. S. Larson. 2010. Assessment of Barriers to Changing Practice as CME Outcomes. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 30(4):237-245. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.20088.

- Bandura, A. 2009. Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In E.A. Locke (Ed)., Handbook of principles of organization behavior. (2nd Ed.). New York: Wiley.