Supervision Strategies and Community Health Worker Effectiveness in Health Care Settings

“Patients will sometimes come to the doctor’s office looking for me. I’m not always there. I’m a partner with the doctor’s office and part of your care team. But you’ll see me in the street, you’ll see me in your community center, at the YMCA, and also at your doctor’s office.” — Orson Brown, Community Health Worker

“Practicing supportive supervision with Community Health Workers is a mutual process where both the supervisor and the CHW have an opportunity to grow, change, and learn. Engaging in this process with CHWs has been one of the supreme joys of my career.” — Noelle Wiggins, Community Health Worker Supervisor

Community Health Worker Integration

Shifts in health care toward value-based payment (i.e., payment based on outcomes rather than units of service) have drawn increasing attention to health-related social needs and social determinants of health. (For more information, see Social Determinants of Health 101 for Health Care: Five Plus Five at https://nam.edu/social-determinants-of-health-101-for-health-care-five-plus-five) As trusted community members, Community Health Workers (CHWs) are well-positioned to support marginalized patients (The manner in which CHWs refer to individuals with whom they work changes by setting. In the community-based programs where CHWs have traditionally worked, individuals are referred to as “participants” or “community members”; in the health care field the individuals are referred to as “patients) in addressing unmet social needs, navigating the health care system, informing health behaviors, and supporting communities in addressing the underlying causes of health inequities. The recent changes in the administration of health care services in the United States have also shifted discussions around the CHW workforce from fundamental considerations such as CHW acknowledgment, inclusion, and remuneration to more sophisticated human resource (See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics, 21-1094 Community Health Workers https://www.bls.gov/oes/2018/may/oes211094.htm) management issues such as inclusion into reimbursement mechanisms, training [1], job satisfaction, engagement, and supervision methodologies [2].

As the CHW workforce is formally integrated into health care systems of different configurations across the globe and in the U.S., (e.g., facilitated by structural, systematized payment mechanisms), issues about human resource management have risen and matured to the extent that research and evaluation on these issues [3] have been called for by the World Health Organization [4]. Tools have been developed and research has been conducted to assess these issues in the international arena, particularly in low- and middle-income settings. For example, the Community Health Worker Assessment and Improvement Matrix toolkit seeks to support the efforts of those assessing, planning, implementing, and managing CHW programs [5]. The toolkit includes programmatic components that address workforce issues like recruitment, roles, training, supervision, performance evaluation, incentives, and advancement opportunities. Another example is the Perceived Supervision Scale, which is an internationally validated tool that measures supervisory experience from the CHW perspective [2]. Specifically concerning the supervision of CHWs, the concept of supportive supervision has been applied to bolster this unique workforce. Supportive supervision emphasizes joint problem-solving, mentoring, and two-way communication between supervisors and those being supervised [6].

In the United States, supportive supervision is crucial to the effective integration of CHWs into institutional workflows, which is in turn fundamental to achieving the mission of health care and public health organizations [7]. The integration of CHWs is a nuanced and contextualized endeavor in both public health and health care settings, and so too must be their supervision to optimize their contributions (See Six Tips for CHW Supervision Success at https://mhpsalud.org/6-tips-for-chw-supervision-success). During a 2019 workshop at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Roundtable on Population Health Improvement (http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/PublicHealth/PopulationHealthImprovementRT/2019-MAR-21.aspx), a panel of CHWs, trainers, supervisors, academics, and payment-mechanism specialists pointed out that across the different contexts in which CHWs work, organizations must be ready to accommodate and support the ways in which CHWs carry out their work and be willing to rethink the manner in which they are supervised, which requires changes to traditional or historical modes of supervision in health care.

Building a CHW Program

Building an effective CHW program requires institutional-level support and buy-in. All team members—from leadership to front desk staff —with whom CHWs will interact need a full understanding and appreciation of CHW history and their unique roles and contributions. Maintaining and supporting the identity of CHWs through their integration into health care and public health settings is of utmost importance [8].

The biomedical model of disease and the clinical modes of operation must not be allowed to overpower the work and approach of CHWs. CHWs, as a group, reflect the communities they serve, as they share the culture, life experience, and socioeconomic background of the patients with whom they work. The effectiveness of their approach is predicated upon the trust that their shared life experiences can help to facilitate. The trust they earn must be preserved and protected. Therefore, suppressing their multifaceted approach to solving community problems through overly restrictive job descriptions and activities solely confined to a clinical setting dilutes the very strength for which they were hired. The hierarchical supervisory approach typical of the health care sector and, perhaps to a lesser degree, public health, is not consistent with the values and approach of the CHW model [9].

Second, entities hiring CHWs must take into account that the CHW approach will be patient-centered6 (i.e., patient-driven actions addressing clinical issues, as well as addressing the emotional, mental, spiritual, social, and financial factors affecting health) and nonepisodic (the time and attention paid to the patient will not end when the chief medical complaint is resolved). As simple as this point may seem, in practice it is difficult. For example, reimbursement mechanisms need to be in place to accommodate the CHW who tends to the patients’ non-clinical needs. CHW roles and activities range from connecting patients to existing health and social services, to providing social support, to sharing culturally appropriate health education, to organizing communities to address persistent health inequities [10]. Clinical staff need to understand that the true “value add” from the CHW model is achieved when CHWs are supported to play a full range of roles [2]. Many of these roles and activities are best undertaken outside the clinic setting, requiring CHWs to spend time in the community.

Third, the clinical or public health setting must have mechanisms in place for integrating the work and the information collected by CHWs. For example, electronic health records (EHRs) can be modified to capture the information collected by CHWs on- and off-site, or other information management systems can be developed or modified to interface with the EHR, and/or be interoperable with community-based platforms [8,11].

Finally, institutions will face five key challenges that often cause CHW programs to struggle: (1) turnover (often related to a lack of hiring guidelines, low salaries, a lack of advancement opportunities, and ineffective or non-existent supervision), (2) a lack of standardized infrastructure, (3) an overly clinical or disease-specific focus, (4) difficulty balancing clinical integration and grassroots community engagement, and (5) low-quality scientific evidence [8,12] (For more information, see From rhetoric to reality—community health workers in post-reform US health care at https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1502569.) Using tested CHW intervention programs that address these issues, rather than “reinventing the wheel,” ameliorates the negative impacts of the aforementioned struggles [12]. To address these challenges, resources like the Penn Center for Community Health Workers (https://chw.upenn.edu/) have emerged. The Penn Center provides resources in leadership, research, and collaboration and innovation services for entities that seek to implement and optimize CHW programs. Other resources have surfaced like statewide professional associations led by CHWs such as the Oregon Community Health Workers Association (ORCHWA) that have centralized training and certification and are collaborating with coordinated care organizations and the state to staff programs with CHWs.

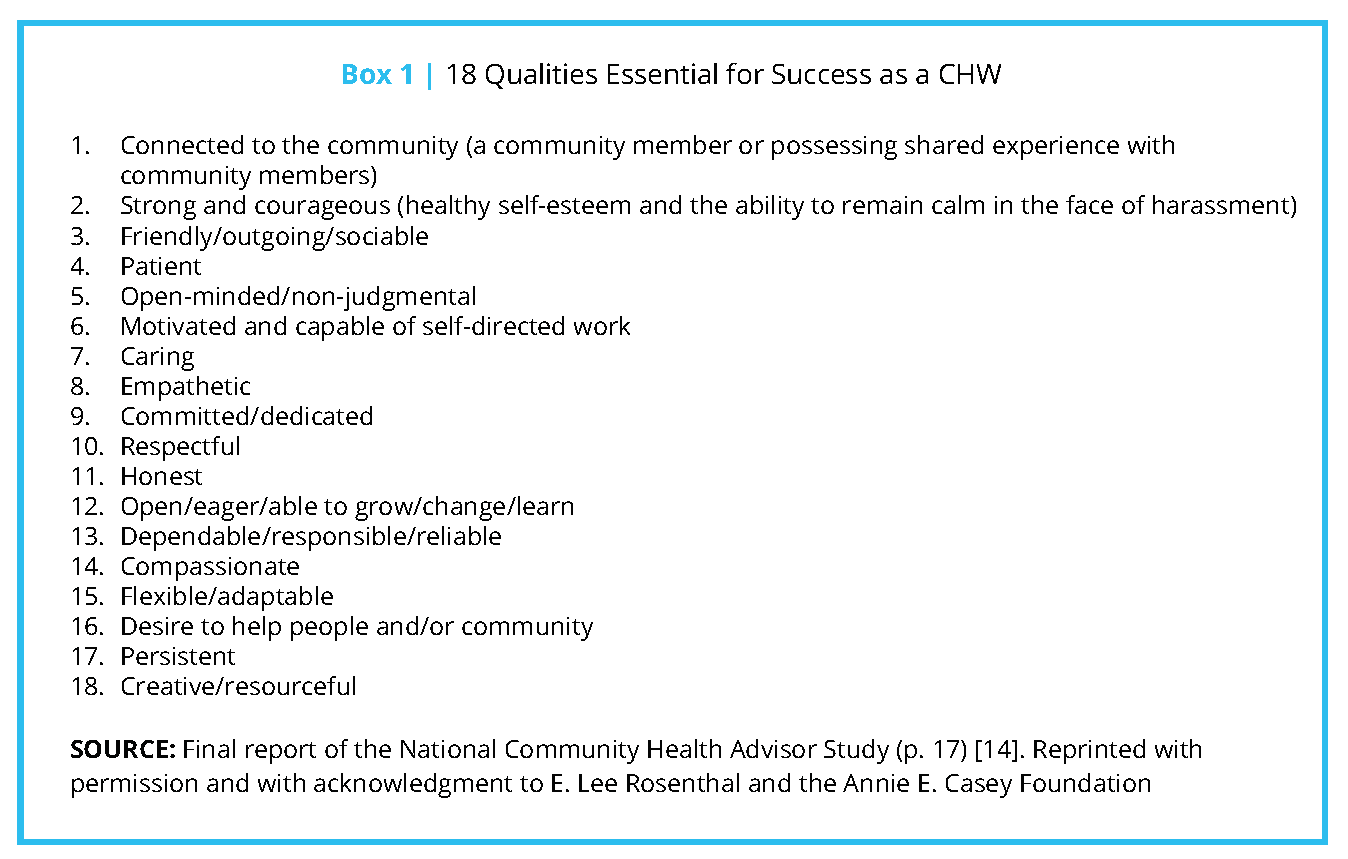

Qualities of a CHW

Effective hiring practices for CHWs differ in substantive ways from those used to hire other health care personnel. (See https://hbr.org/2019/10/health-care-providers-arehiring-the-wrong-people.) Being a CHW is not merely a job, but a calling; success in the role depends on certain personal qualities such as being a natural helper, being creative, and being resourceful [13]. CHWs regard themselves as being altruistic, empathetic, trustworthy, flexible, perceptive, and creative, and these aspects are fundamental to their ability to be effective. The importance of these and other qualities of CHWs has been documented. For example, the 1998 National Community Health Advisor Study [14] identified a list of 18 qualities as essential for success as a CHW (see Box 1).

A more recent study, the Community Health Worker Core Consensus, or C3 Project, (see the Community Health Worker Core Consensus Project at https://www.c3project.org) upholds and leverages the findings of the National Community Health Advisor Study, is a tool for understanding CHW roles and competencies, and can help inform the supervisory relationship.

Because of the heavily interpersonal nature of community health work, the personality traits of CHWs are especially important, and the hiring entity has to first identify individuals with these characteristics and then preserve, leverage, and maintain the assets these individuals already possess. Although any interview process is laden with the subjective impressions of employers, when hiring a CHW, supervisors would be prudent to assess to what extent applicants possess the qualities described above. This can be achieved by using a combination of direct questions, scenario-based questions, and role-playing. By presenting situations in which CHWs can commonly find themselves and asking candidates to explain or demonstrate how they would react, employers can obtain a more nuanced and realistic understanding of applicants’ qualities.

CHW Training

Providing effective initial and ongoing training for CHWs is a crucial element of creating a workplace that nurtures and capitalizes on CHW qualities. Workplace readiness will be specific to the location where the CHW program is being implemented but generally entails equipping CHWs with the knowledge to function within the program, unit, and hiring institution. Such onsite training may include basic activities like the orientation to policies and standard operating procedures and EHR training, among other onboarding activities. It is absolutely essential that CHWs also participate in core competency development that builds on what CHWs already know and helps them further cultivate skills that have been identified as crucial across clinical and community settings [15], such as trauma-informed care (this concept is further discussed later in this paper). Moreover, the use of Popular/People’s Education, an empowering philosophy and methodology most associated with the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, has been identified as a best practice in CHW training [16,17]. Popular Education is based on two main ideas that are also fundamental to the CHW model: first, that people most affected by inequities are the experts about their own experience, and second, that the knowledge gained through life experience is just as important, and in some cases more important, than the knowledge gained through formal education [16]. This non-hierarchical philosophy should guide all clinicians’ interactions with CHWs.

Whether working primarily in the community or the clinical setting, time and space need to be allocated for CHWs to pursue professional development and continuing education opportunities. Such activities may include trainings in a variety of topics or informal gatherings designed to supplement both the clinical and community knowledge of CHWs. The recently formed National Association of Community Health Workers may provide a venue to identify and disseminate such opportunities, in addition to existing regional and state-based associations.

Supportive Supervision in Practice

Historically, and across professions, supervision has been an endeavor of task oversight and punitive, critical corrective actions [18]. However, alternative modes of supervision have recently emerged, including supportive supervision. Supportive supervision is considered a best practice for CHW supervision in international settings and includes collaborative reviews, observations, monitoring, constructive feedback, participation, problem-solving, and training and education [19]. Such a comprehensive supervisory strategy is of particular importance to the success of CHW programs and facilitates the empowerment of CHWs across disparate health care settings [20]. The bulk of published literature about CHWs and supportive supervision has been focused on international settings [21,22] where it has shown to positively influence efficiency and sustainability by increasing CHW motivation and retention [18,23]. To be implemented, supportive supervision requires shifts in behaviors and attitudes, time investments, and is driven by leadership [6].

Supervisor Roles and Duties

Supportive supervision has been identified as a motivator for CHWs [23] and as such, institutional structures should be present to establish and sustain the practice. The institution should invest in a supportive supervision program, and unit budgets should allocate funds for supervisor training, communication approaches, and team-building activities for CHWs [21].

In addition to institutional investments, supportive supervisors can strive to be available to CHWs, provide trauma-informed supervision, prioritize the safety of CHWs, and provide constant monitoring and coaching. These characteristics of supportive supervision are explained below.

Be available to CHWs. In terms of its configuration, supportive supervision can be broken down into two components: technical and psychosocial [18]. This emerging structure has been informed by the mental health field, where there is a division of supervision by tasks: the administrative and the clinical. The former involves supervision of tasks by an onsite supervisor, and the latter involves clinical supervision by an appropriate clinician, who may be on- or off-site but who is, nevertheless, available to CHWs on a regular basis. The constant interaction and communication facilitates timeliness in reviewing patient cases and help with real-time emergencies.

Provide trauma-informed supervision. The psychosocial component of supportive supervision is focused on the recognition that CHWs may face the same challenges that they are helping patients address [18]. Supportive supervision for CHWs must be protective, given the nature of the role CHWs perform. As members of communities most affected by inequities, CHWs often experience both historical and vicarious trauma, as well as personal and individual trauma. Supportive supervision for CHWs includes a trauma-informed approach [24], (See the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach at https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4884.pdf) which means applying the principles of trauma-informed care in the supervisory relationship. Supportive and trauma-informed supervision is based on an ongoing relationship that is built and sustained intentionally over time through “sharing experiences, listening reflectively, and communicating mindfully” [25].

Prioritize the safety of CHWs. Safety is always a concern for CHWs, as they may find themselves in potentially dangerous situations in patients’ homes and communities. CHWs often work with patients who face medical, psychiatric, or domestic violence emergencies. For example, at the Penn Center, CHWs are encouraged to tell their supervisors any time they feel unsafe with a patient’s situation. By using smartphones and asking CHWs to send text messages to their supervisors during any home visit, supervisors can track the CHW’s location and alert police in the event of an emergency. In less emergent situations, Penn Center supervisors address the situation by calling a safety huddle with the program director to discuss a plan that can be implemented to ensure the safety of the CHW. For example, if a CHW meets a new patient and hears the patient describe drug activity and shootings on their residential block, the CHW informs the supervisor, who then convenes a safety huddle and the group develops a plan to meet this patient at a different location. The director also shares this safety information with all other staff so that they can take necessary precautions.

Provide constant monitoring and coaching. It would be overwhelming for a CHW to do this type of high-acuity work without the constant and careful monitoring and coaching afforded by supportive supervision. Because of the exposure to potentially traumatic situations on a frequent basis, CHWs can experience high levels of secondary trauma that can lead to burnout if not addressed [26]. It is not surprising that the absence of supportive supervision significantly contributes to the high attrition of CHWs who work in clinical settings [12]. The deleterious effects that stressful exposures may have on CHWs’ motivation and retention [22] can be ameliorated through frequent communication between the supervisors and CHWs afforded by supportive supervision. Team-building activities during staff development meetings may help foster peer support as well.

Supervisors should not only support CHWs, but also hold them accountable for high performance based on clearly defined metrics for success (e.g., patient satisfaction, achievement of patient-centered goals, improvements in health status, reductions in costly hospitalization, etc.). Performance assessment requires the close monitoring of a variety of data sources. For example, at the Penn Center [27], supervisors assess performance by reading CHW documentation, reviewing dashboards of outcomes, and actually calling patients to ask about their experience working with their CHWs. Using software applications that allow supervisors to track outcomes and create objective performance assessments can help and could be superior to anecdotal feedback alone as a performance metric.

It is important that interactions between the CHW and their supervisor occur both on a regular basis and as needed. Regular meeting times can be used to discuss and review patient caseloads, troubleshoot problems, develop strategies to address patient needs, and ensure follow-up. In emergencies (e.g., when a patient is contemplating suicide or in other perilous situations), it is imperative that supervision is immediately available and reliable.

Qualities and Skills of Supportive Supervisors

Most CHWs, when asked what they most want from their supervisors, say some version of the following—“An understanding of who CHWs are and what we do.” This includes understanding the social justice origins of the CHW model, the core roles and competencies of CHWs, and recent trends and developments in the CHW field. The ideal way to gain these competencies is through experience as a CHW; however, finding community-based experience in clinical settings is uncommon.

Supervising anyone is difficult work, and supervising CHWs is a special task. When placing individuals in supervisory roles, health care institutions should consider the following: can the supervisor be firm and flexible at the same time? Policy must be upheld, but supervisors have to be able to relate to and have compassion when interacting with their team to help avoid the burnout of CHWs. As if that balance were not tenuous enough, supervisors must also be able to champion and advocate for their CHWs within health systems or the larger institutions in which they work.

Supervisors with knowledge and experience with the community and its resources will allow them to have the best vantage point for supervising this grassroots workforce. For example, in the IMPaCT model [28], supervisors play a critical role and are typically individuals with a master’s degree in social work or public health who provide real-time support, ongoing training, and help with clinical integration. Managers nurture high performance through weekly assessments that include audits of documentation, observation of CHWs in the field, phone calls to patients, and review of a performance dashboard [27].

Historically, supervisors of CHWs were often individuals with backgrounds in social work or public health. As CHWs shift into health care, clinicians (e.g., nurses, doctors) are often asked to supervise. This represents a challenge in some ways because the underlying paradigm of CHW work is different from the biomedical/clinical paradigm. As mentioned before, clinicians need to be aware and ultimately understand at a deep level that CHWs’ expertise is equal to and just as valuable as their own, as well as being fundamentally different. Clinicians need to heed Giblin’s dictum that CHWs are professionals whose professionalism comes not from formal degrees but from their life experience [29]. Developing this understanding may be facilitated by becoming familiar with the principles and practice of Popular/People’s Education as previously mentioned.

For supervisors with a clinical background, it must be acknowledged that although medical issues are part of what CHWs are focused on, they are only one part of a much greater context of social dynamics. Clinical supervisors will have to apply an equal emphasis on the social aspects of health, even though that is not the norm. The actions taken to address the social component of health is critical for patients, which requires a collective effort from different sectors, an effort that CHWs can greatly facilitate.

Conclusion

In the U.S., the integration of CHWs in health care institutions has been encouraged, in part, by a shift to value-based payment. The ability of CHWs to provide non-episodic and patient-centered care along with their help to identify and address unmet social needs is a welcome opportunity for both quality of care and population health improvement. CHW integration has human resource management considerations that range from identifying the qualities in individuals that are essential for CHW success during recruitment, to having the structures and practices in place that will help CHWs in carrying out their mission, like training and supervision. The quality of the supervision provided must be supportive, which is seldom the practice in health care settings, where vertical/hierarchical practices are the norm. The health care institution can itself encourage supportive supervision by allocating the resources needed (e.g., workflow considerations, and budget for training) to practice supportive supervision. Given the unique position of CHWs in the health care system, supervisors of CHWs will have to, at a minimum, be continuously available, provide trauma-informed supervision, prioritize safety, and monitor and coach CHWs. Being able to provide supportive supervision also requires that the supervisor be both knowledgeable about and experienced with the community CHWs serve. Supportive supervisors in the health care setting must understand and accept that the expertise of CHWs is just as valuable as their own and crucial to the successful integration of CHW programs in health care settings.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! Community health workers can be critical in shifting health care toward better population health outcomes but need to be supported and supervised in ways that can conflict with the traditional health system. Read more in a new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202003c

Tweet this! Community health workers can be critical in shifting health care toward better population health outcomes but need to be supported and supervised in ways that can conflict with the traditional health system. Read more in a new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202003c

![]() Tweet this! Community health workers bring a unique approach to caring for their patients, and as such, the way they are supported and managed must be unique as well. Read more about supportive supervision and how CHW’s can benefit patients: https://doi.org/10.31478/202003c #NAMPerspectives

Tweet this! Community health workers bring a unique approach to caring for their patients, and as such, the way they are supported and managed must be unique as well. Read more about supportive supervision and how CHW’s can benefit patients: https://doi.org/10.31478/202003c #NAMPerspectives

![]() Tweet this! Supervisors with a clinical background must acknowledge that medical issues are only some of what community health workers help their patients deal with, and the social aspect of health is just as critical. Read more in a new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202003c

Tweet this! Supervisors with a clinical background must acknowledge that medical issues are only some of what community health workers help their patients deal with, and the social aspect of health is just as critical. Read more in a new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202003c

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- Rosenthal, E. L., J. N. Brownstein, C. H. Rush, G. R. Hirsch, A. M. Willaert, J. R. Scott, L. R. Holderby, and D. J. Fox. 2010. Community health workers: Part of the solution. Health Affairs 29(7):1338–1342. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0081

- Vallières, F., P. Hyland, E. McAuliff e, I. Mahmud, O. Tulloch, P. Walker, and M. Taegtmeyer. 2018. A new tool to measure approaches to supervision from the perspective of community health workers: A prospective, longitudinal, validation study in seven countries. BMC Health Services Research 18(1):806. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3595-7

- Abrahams-Gessel, S., C. A. Denman, C. M. Montano, T. A. Gaziano, N. Levitt, A. Rivera-Andrade, D. M. Carrasco, J. Zulu, M. A. Khanam, and T. Puoane. 2015. Training and supervision of community health workers conducting population-based, noninvasive screening for CVD in LMIC: Implications for scaling up. Global Heart 10(1):39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2014.12.008

- Maher, D., and G. Cometto. 2016. Research on community-based health workers is needed to achieve the sustainable development goals. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 94(11):786. Available at: https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/94/11/16-185918/en/ (accessed September 2, 2020).

- Crigler, L., K. Hill, R. Furth, and D. Bjerregaard. 2011. Community Health Worker Assessment and Improvement Matrix (CHW AIM): A toolkit for improving CHW programs and services. Bethesda, MD: USAID.

- Marquez, L., and L. Kean. 2002. Making supervision supportive and sustainable: New approaches to old problems. MAQ Paper No. 4. Washington, DC: USAID.

- Payne, J., S. Razi, K. Emery, W. Quattrone, and M. Tardif-Douglin. 2017. Integrating community health workers (CHWs) into health care organizations. Journal of Community Health 42(5):983–990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0345-4

- Garfi eld, S., and S. Kangovi. 2019. Integrating community health workers into health care teams without co-opting them. Health Affairs Blog. https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20190507.746358

- Balcazar, H., E. Lee Rosenthal, J. Nell Brownstein, C. H. Rush, S. Matos, and L. Hernandez. 2011. Community health workers can be a public health force for change in the United States: Three actions for a new paradigm. American Journal of Public Health 101(12):2199–2203. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300386

- Rosenthal, E. L., P. Menkin, and J. St. John. 2018. The Community Health Worker Core Consensus (C3) project: A report of the C3 project phase 1 and 2. El Paso, TX: Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso.

- Penn Center for Community Health Workers. 2018. The IMPaCT model. Available at: https://chw.upenn.edu/about (accessed September 2, 2020).

- Kangovi, S., D. Grande, and C. Trinh-Shevrin. 2015. From rhetoric to reality—community health workers in post-reform U.S. health care. New England Journal of Medicine 372(24):2277. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1502569

- Wiggins, N., and A. Borbon. 1998. Core roles and competencies of community health advisors. In The final full report of the National Community Health Advisor Study: Weaving the future. The University of Arizona. Available at: https://crh.arizona.edu/sites/default/fi les/pdf/publications/CAHsummary-ALL.pdf (accessed September 2, 2020).

- The University of Arizona. 1998. A summary of the National Community Health Advisor Study: Weaving the future. Available at: https://crh.arizona.edu/sites/default/fi les/pdf/publications/CAHsummary-ALL.pdf (accessed September 2, 2020).

- Rosenthal, E. L., and N. Wiggins. 2015. Community health workers: Advocating for a just community and workplace. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management 38(3):204–205. Available at: https://www.nursingcenter.com/journalarticle?Article_ID=3130109&Journal_ID=54005&Issue_ID=3130105 (accessed September 2, 2020).

- Wiggins, N., A. Hughes, A. Rodriguez, C. Potter, and T. Rios-Campos. 2014. La palabra es salud (the word is health): Combining mixed methods and CBPR to understand the comparative effectiveness of popular and conventional education. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 8(3):278–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689813510785

- Wiggins, N., S. Kaan, T. Rios-Campos, R. Gaonkar, E. R. Morgan, and J. Robinson. 2013. Preparing community health workers for their role as agents of social change: Experience of the community capacitation center. Journal of Community Practice 21(3):186–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2013.811622

- Crigler, L., J. Gergen, and H. Perry. 2013. Supervision of community health workers. Washington, DC: USAID/Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program.

- Hill, Z., M. Dumbaugh, L. Benton, K. Kaellander, D. Strachan, A. Ten Asbroek, J. Tibenderana, B. Kirkwood, and S. Meek. 2014. Supervising community health workers in low-income countries–a review of impact and implementation issues. Global Health Action 7(1):24085. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.24085

- Torres, S., H. Balcázar, L. E. Rosenthal, R. Labonté, D. Fox, and Y. Chiu. 2017. Community health workers in Canada and the U.S.: Working from the margins to address health equity. Critical Public Health 27(5):533–540. Available at: http://globalhealthequity.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Community-health-workers-in-Canada-and-the-US-working-from-the-margins-to-address-health-equity.pdf (accessed September 2, 2020).

- Rabbani, F., L. Shipton, W. Aftab, K. Sangrasi, S. Perveen, and A. Zahidie. 2016. Inspiring health worker motivation with supportive supervision: A survey of lady health supervisor motivating factors in rural Pakistan. BMC Health Services Research 16(1):397. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1641-x

- Strachan, D. L., K. Källander, A. H. ten Asbroek, B. Kirkwood, S. R. Meek, L. Benton, L. Conteh, J. Tibenderana, and Z. Hill. 2012. Interventions to improve motivation and retention of community health workers delivering integrated community case management (ICCM): Stakeholder perceptions and priorities. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 87(5_Suppl):111–119. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0030

- Ludwick, T., E. Turyakira, T. Kyomuhangi, K. Manalili, S. Robinson, and J. L. Brenner. 2018. Supportive supervision and constructive relationships with healthcare workers support CHW performance: Use of a qualitative framework to evaluate CHW programming in Uganda. Human Resources for Health 16(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0272-1

- SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2014. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4884.pdf (accessed September 2, 2020).

- Sofer, O. J. 2018. Say what you mean: A mindful approach to nonviolent communication. Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications.

- Berthold, T. 2016. Foundations for community health workers. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Kangovi, S., N. Mitra, L. Norton, R. Harte, X. Zhao, T. Carter, D. Grande, and J. A. Long. 2018. Effect of community health worker support on clinical outcomes of low-income patients across primary care facilities: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine 178(12):1635–1643. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4630

- Kangovi, S., T. Carter, D. Charles, R. A. Smith, K. Glanz, J. A. Long, and D. Grande. 2016. Toward a scalable, patient-centered community health worker model: Adapting the impact intervention for use in the outpatient setting. Population Health Management 19(6):380–388. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2015.0157

- Giblin, P. T. 1989. Effective utilization and evaluation of indigenous health care workers. Public Health Reports 104(4):361. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1579943/ (accessed September 2, 2020).