The ROI of Health and Well-Being: Business Investment in Healthier Communities

ABSTRACT | Businesses are gaining a greater understanding of the effect that employee health and the health of the communities in which businesses reside has on their success. No matter the size, type, or location of a business, many of them are proactively looking to improve health in the communities where they operate. To better understand businesses’ growing relationship to community health, the US Chamber of Commerce Foundation Corporate Citizenship Center (USCCF) partnered with the Action Collaborative on Business Engagement in Building Healthy Communities (the Collaborative), a convening activity of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Roundtable on Population Health Improvement. This paper is a product of that partnership, exploring the business motivation for investing in community health, the processes involved in that effort, and the challenges stakeholders faced when pursuing these initiatives.

Introduction: The State of Workers’ Health in the United States

American labor productivity has steadily increased over the past several decades, augmenting businesses’ reliance on the workforce to sustain their revenue and growth [1]. This economic and business advancement is heavily influenced by the health, or the lack thereof, of the 144 million currently employed Americans. Statistics offer a sobering look at the state of health among the working-age US population:

- Seventy-one percent of Americans age 20 and over are overweight or obese (body mass index, or BMI, equal to or greater than 25). Thirty-eight percent are obese (BMI equal to or greater than 30) [2].

The Effect on Businesses: The cost of unhealthy employees to businesses is significant to their bottom line. Obese men incur $1,152 more in direct annual health costs than do men of normal weight, and obese women incur $3,613 more than do women of normal weight [3].

- Twenty-five percent of Americans age 18 and over had at least one heavy drinking day (five or more drinks for men and four or more drinks for women) in the past year [4].

The Effect on Businesses: Excessive drinking costs US employers $179 billion annually in workplace productivity losses [5].

- Seventeen percent of adults 18 and over smoke [6].

The Effect on Businesses: Partial-day absenteeism because of smoke breaks cost an estimated $13 per workday, accumulating to an additional $3,077 per year per worker. Health care costs for smokers are about $2,056 per year more than the costs for nonsmokers [7].

- Seven percent of individuals 18-39 years old and 10 percent of 40-59-year-olds have moderate to severe depressive symptoms [8].

The Effect on Businesses: Workers in the United States who, at some point in their lives, have received a diagnosis of depression miss an estimated 68 million more days of work each year than their counterparts who have not been depressed—resulting in an estimated cost of more than $23 billion in lost productivity annually to US employers [9].

Moreover, a World Economic Forum report (2011) estimates a cumulative economic output loss of $47 trillion over the next two decades from noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, cancer, diabetes, and mental health, representing 75 percent of global GDP in 2010 [10].

The Importance of Business Participation in Community Health

Business investment in health in the twenty-first century has become increasingly common as the private sector seeks to improve the health of their employees as part of their corporate citizenship efforts, find new business opportunities, and ultimately improve their return on investment (ROI) both socially and financially. Health and wellness programs, run by businesses or offered through employee insurance plans, are now standard at large businesses and are gaining traction among small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs). As businesses acknowledge the importance of health in the workplace, they have also begun to recognize the relationship between their employees’ health and the communities where their employees (and their families) and customers live. At the end of the workday, employees and customers still return home to communities that may be food deserts, have poor infrastructure, or have limited access to good-quality health care. Improving community health—long considered solely the responsibility of the public sector—is gradually being embraced by the private sector [11].

To gain more insight into businesses’ relationship to community health, the US Chamber of Commerce Foundation Corporate Citizenship Center (USCCF) partnered with the Action Collaborative on Business Engagement in Building Healthy Communities (the Collaborative). The Collaborative is a convening activity of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Roundtable on Population Health Improvement composed of private, public, and nonprofit sector parties that endeavor to improve health in US communities. This paper is part of the Collaborative’s effort to promote business engagement in strategies for improving community health with a focus on the health and economic well-being of businesses, workers, and communities.

Typically, community-based public health-related programs have been tied to healthy behaviors and clinical care. In recent years, however, public health practitioners have taken a more expansive view of community health, its effect, and the stakeholders involved in improving it. As defined, community health refers to the health status of a specific group of people, or community, and the actions and conditions that protect and improve the health of the community. Those individuals who make up a community live in a somewhat localized area under the same general regulations, norms, values, and organizations [12].

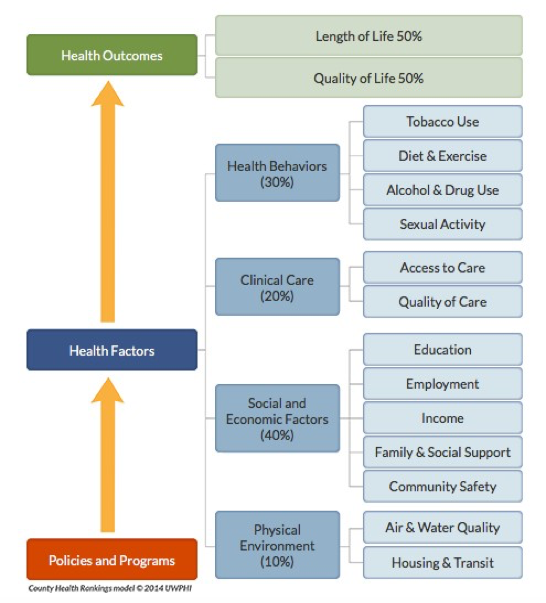

A framework for understanding the different factors and potential opportunities for interventions that influence population health is offered by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s County Health Rankings & Roadmap (CHRR) (see Figure 1). This framework provides a useful graphic representation of the factors that contribute to health outcomes.

Figure 1 | County Health Rankings & Roadmap

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from the University of Wisconsin

Most workplace wellness programs are structured to address improvement in healthful behaviors and clinical care without including external socioeconomic and environmental interventions (e.g., access to green spaces, active transportation, healthy housing, and nutritious foods) that also influence employee health [13]. Given the sheer amount of time that people spend outside of the workplace, work-site-based wellness programs offer only a partial solution to a complex problem centered in a company’s home community. For example, some major industries, such as retail and manufacturing, are more likely to be in counties with poor health, emphasizing the need to confront health issues outside the workplace [14].

However, there are businesses investing in community health. Researchers with the Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO) cited several reasons for doing so:

- Enhanced reputation in the community as good corporate citizens

- Cost savings that would increase over time

- Job satisfaction

- Healthier, happier, and more productive employees

- Healthy, vibrant communities that draw new talent and retain current staff

- Compliance with regulations

- Enhanced consumer health [15,16,17]

Common Business Strategies to Invest in Community Health

Some of the common strategies that companies have used to invest in community health are highlighted below in Boxes 1-3 [18].

Philanthropy, Health Advocacy, Employee Volunteering

Efforts such as targeted philanthropic giving, participating in health advocacy, employee volunteering, and employees serving on the boards or advisory councils of health initiatives further extend the potential of businesses to positively influence community health. Under the CHRR framework, many businesses’ corporate citizenship initiatives contribute to overall community health and well-being. Business environmental sustainability programs, for example, can have a direct effect on community health through better air, water, and soil quality. Furthermore, the community participation associated with employee volunteer programs has been demonstrated to improve health and may therefore also directly serve to promote employee health [19] (see Box 1).

Innovative Products and Services

Businesses can also directly affect community health through their products and services. The work of Michael Porter and Mark Kramer on creating “shared value” is a model that some businesses are using to change their products and services to generate greater innovation and growth for the company while simultaneously providing greater benefits to society [14,16,20,21]. As consumers have become more health and socially conscious, businesses have innovated to meet their demands, influencing community health in the process. The health care industry has a natural advantage to improving community health given its business goals, but businesses outside the health care industry may also use their products and services to improve community health (see Box 2).

Partner with Other Stakeholders

Individual and community health is a product of the interaction of societal, economic, and environmental factors. Given these interrelated factors that influence health, businesses rarely execute a program without other community stakeholders. Partnering with external organizations on community health initiatives enables businesses to improve the health of their workforce through community and workplace health promotion; increase human capital through employee recruitment, engagement, and retention; and profit from business opportunities to develop healthful products and services that respond to market demands [14,22]. Such partnerships consist of nonprofit or public sector organizations, trade associations, or local civic organizations, all of which provide opportunities for businesses to access existing community health programs or launch new initiatives (see Box 3).

Partnering with external organizations can also serve as a way to overcome some of the barriers that business faces, particularly if they are outside the health care industry, when considering how to extend health initiatives outside the workplace. The following are some of the barriers for businesses engaging in community initiatives:

- A lack of understanding, strategy, or resources

- The complexity of community health problems

- A lack of trust or experience between businesses and partnering organizations

- Difficulty in navigating policies and regulations

- A need to shift leadership philosophy [17]

Data and metrics have become progressively integrated into business activities as big data analysis and technological advancements allow for the mining of myriad data types [15,23]. However, comprehensive assessment of health outcomes can add a layer of complexity to business participation in such endeavors. These are some of the challenges businesses face in assessments:

- Measuring cause and effect. Because numerous factors can contribute to the health of a community and there are frequently other programs attempting to effect change as well, determining whether a business’s particular program had any influence on health outcomes can prove difficult, particularly in communities with a wide array of health challenges or a number of different community health programs.

- Internal business capacity. Assessing a program requires dedicated funding and a skill set that may not be common to businesses, especially smaller and midsized ones. In addition, measuring health outcomes is a multiyear commitment that can be daunting to any organization to manage.

- Balancing business and programmatic ROI. Given the quick pace of business and a focus on immediate results, health outcomes assessment is a more extensive process that may not coalesce with business needs and desires.

- Use of data. Basic, narrative data from community health programs is usually collected to enhance business marketing and promote corporate citizenship activities. Businesses may not be interested in more in-depth analysis, and senior management may not require it to justify continuing programming.

A solution to these challenges is partnering with an organization or academic institution that has the capability of assessing health outcomes. Finding an able partner may exceed the commitment a business is willing to make, depending on its goals for a community health program.

Research Questions

To date, little research exists on the differences in community health involvement based on business size or the role that member-based organizations (e.g., trade associations, local civic organizations, and so on) in community health can play in connecting businesses to communities. This paper therefore explores what, if any, variations there are in the case of large companies compared with SMEs and member-based organizations in community health efforts.

This paper is based on research conducted to address several questions about businesses and community health:

- Why are businesses investing in community health? What is their motivation?

- Do businesses see programs that focus on social, economic, and environmental factors in their communities as efforts related to community health?

- What types of community health activities are businesses engaged in?

- What processes do businesses undertake to establish and run community health programs? What challenges have businesses faced?

- Does community health engagement vary by the size of the business?

- How does private enterprise engagement in community health differ from that of member-based organizations (e.g., trade associations, civic organizations)?

- What role do member-based organizations play in connecting businesses to communities?

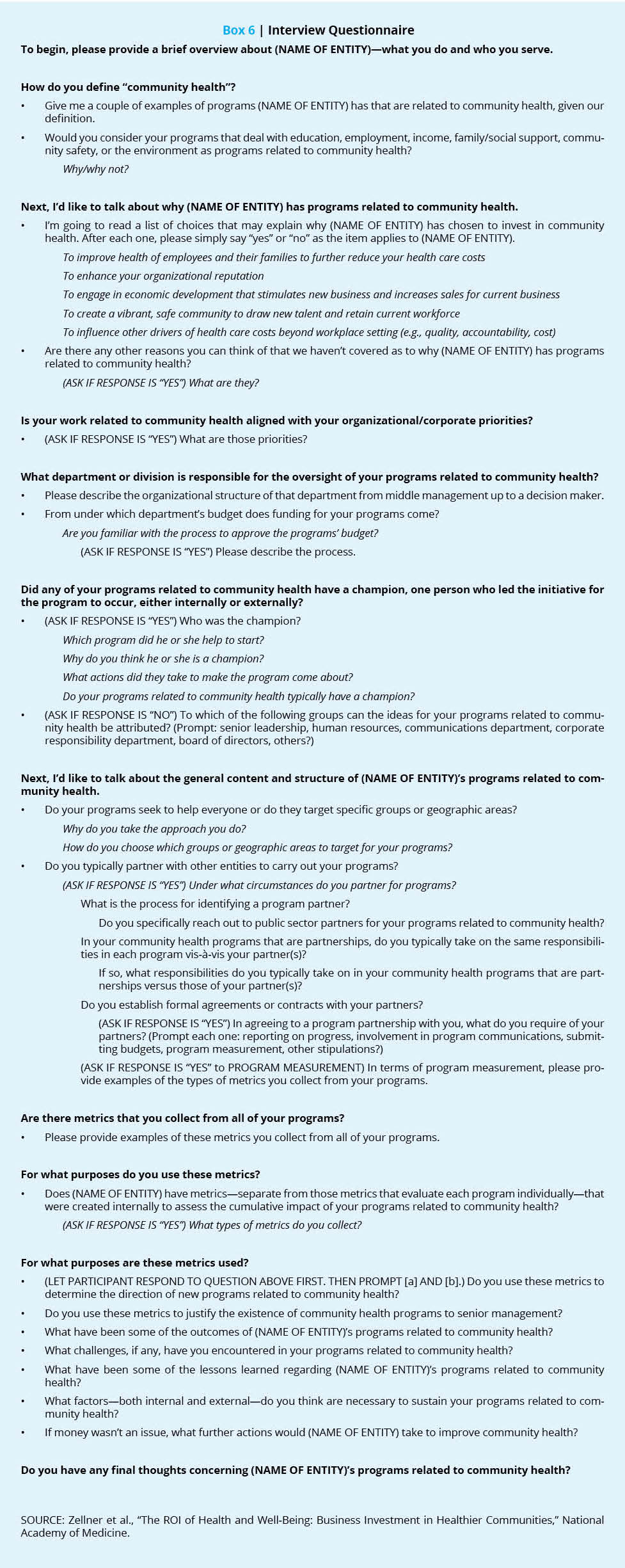

To answer these questions, in-depth interviews were conducted with a variety of entities involved in business programs in community health. The authors spoke with people in two larger businesses (more than 500 employees), three small and medium-sized businesses, two trade associations, one state civic organization, and one city civic organization—all doing work in community health—in fall 2016. The authors asked them about their involvement in community health and the steps they undertake to develop, run, and evaluate their programs (see Box 4 for a list of interviewees and see Box 6 for the interview questionnaire). Follow-up and informal conversations with a broader assortment of businesses connected through the Collaborative and through USCCF helped frame the findings of the in-depth interviews by including geographic, systematic, or programmatic context.

In this paper, the authors focus on partnership programs and business products and services that can transform community health. Though other activities such as philanthropic giving can contribute to community health efforts, this investigation specifically probes how direct business participation affects the health of communities. Also, although internal employee wellness programs occasionally came up in interviews, our research does not concentrate on them. This research found that they were too varied and generally beholden to too many policies and regulations to include in an analysis such as this, although the efficacies of some workplace wellness programs can be seen in the work of Berry et al. (2010) [24]. Finally, for similar reasons, the research touches upon the involvement of the public sector in business community health but do not specifically cover public-private partnerships.

Findings: Business Motivation for Investing in Community Health

Businesses commonly cited five reasons for getting involved in community health [15]:

- Improve health of employees and their families to further reduce health care costs.

- Enhance organizational reputation.

- Engage in economic development that stimulates new business and increases sales for current business.

- Create a vibrant, safe community to draw new talent and retain the current workforce.

- Influence other drivers of health care costs beyond the workplace setting (e.g., quality, accountability).

Interviews with businesses of varying sizes and member-based organizations engaged in community health reveal that these groups are motivated by dual purposes: the drive and passion to improve health in their communities and the desire to enhance business ROI. When probed, the vast majority of businesses and member-based organizations interviewed agreed that all the reasons cited in the HERO report were motivations for their businesses and business members (in the case of the member-based organizations) to invest in community health. Some of the businesses said that enhanced organizational reputation and the creation of new business and increased sales were not direct reasons for their involvement in community health programs but were by-products of their initiatives.

Businesses also expressed that their investment in community health reflects a genuine concern about communities, particularly those communities where the businesses are located. Giving back, some said, is “the right thing to do” since it is the community that keeps them in business. For those companies whose corporate priorities and mission depend on health, the imperative of their vision is what guides them. The businesses and member-based organizations believe they understand the health challenges faced by people in their communities and want to be part of the solution.

Another less common motivation for becoming involved in community health is to fill an unmet need in a community. As the largest employer in several rural communities in southern Indiana where health care professionals are sparse, Jasper Engines has established wellness clinics to help employees and their families more easily seek care, saving employees and their families hours of travel time to see general practitioners or specialists. The company also organizes a health fair and 5k run to involve the broader community in wellness activities and improved health.

The business member-based organizations—the Greater Philadelphia Business Coalition on Health (GPBCH), the Wellness Council of Indiana (Wellness Council), and the Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA)—thought that although members join for many reasons, some of their members specifically joined so that they could connect to communities and participate in community health efforts with other like-minded businesses. Some of the reasons for membership in their organizations that they cited are permitting a business to collectively support community health initiatives when they do not have the capacity to run a community health program alone, using the member-based organization to expand their community health outreach efforts, and providing businesses access to other businesses to share locally-focused lessons learned or best practices in community health.

The Nuts and Bolts

The large and medium-size businesses that we investigated and interviewed house their community health programs in a variety of corporate divisions: corporate social responsibility, human resources, risk management, and marketing/sales, demonstrating the challenges that external, or even internal, groups may experience in identifying the principal liaison for community health programs. In the smallest organization interviewed, Ted’s Shoes and Sport with 10 employees, the owner of the business, Ted McGreer, handles community health programming personally. As a very small business involved in community health, Ted’s Shoes and Sport empowers employees to get involved in the decision-making process. Every Monday, the full staff reviews submissions that have come in the prior week for community health partnerships and sponsorships. They then collectively make decisions about the community health efforts that Ted’s Shoes and Sport will pursue.

Businesses mostly identify programs focusing on social issues, economic issues, and/or the environment, all identified as health issues in the CHRR framework, as related to community health. They recognize that health is multifaceted and that programs concerning these issues influence health and well-being. However, the programs of these businesses typically focused on traditional healthful behaviors or clinical care.

In terms of funding for programs, budgets for community health programs in the businesses interviewed were created by those managers in charge of them. Community health initiatives at GPBCH, the Wellness Council, and GMA are funded from a variety of sources, including membership dues, and supplemented with funds from sponsorships, trainings, consulting, grants, or special member assessments. Among those businesses and member-based organizations that have a board of directors, the board approves the budget for community health. Although a budget for community health programs is established, several entities interviewed said that there is flexibility regarding additional programs, which makes them more versatile so they can pursue new opportunities.

Partnerships

Ways to determine which community health programs to pursue vary, but partnering almost always took place at all the businesses interviewed. The businesses frequently field proposals for partnerships by nonprofit and other community groups interested in improving community health and programs. However, we found that the businesses also initiate relationships with specific partners for programs related to the partner’s expertise.

Regardless of who initiates the partnership, businesses often have criteria for the programs they want to invest in that are tied to their corporate priorities or mission. Whereas some community health programs of the interviewees were broad reaching, affecting the general population, more frequently they focused on specific groups or needs related to the businesses’ core competencies or markets. Once partnerships are formed, responsibilities and expectations between companies and local health nonprofits are usually established informally, except in instances with concrete deliverables or where funds are exchanged.

Member-based organizations, which are also pursued by community health groups to create joint initiatives, frequently solicit feedback from their membership to help decide programmatic direction. With the member-based organizations, the membership often decides which communities to target.

Among those partnership elements that were common to both businesses and the member-based organizations, the majority of interviewees said that government entities had been involved in at least one community health program with them. As for the contractual aspects of partnerships, both groups said that their partnerships in community health are typically informal, i.e., they do not involve written contracts or agreements unless they entail specific deliverables or the exchange of funds from one organization to the other.

Champions

Each of the businesses and member-based organizations found that a champion was essential to the realization of community health programs. For some of the interviewees, the person in charge of community health programs at the business or member-based organization was the natural champion because it was his or her responsibility to organize community health activities and create programs that serve the best interests of the business or organization. In cases where there was no existing director of community health programs, the organizational role and title of that person varied. At Jasper Engines, for example, duties were shared between the directors of the health and safety department and the department of corporate compliance and health care.

Once the business and nonprofit partners form a community health program, other champions may appear to trumpet the cause. In the case of GPBCH and the Wellness Council, the organizations have rallied their members to inform them of the importance of their programs. For example, GPBCH encourages member businesses to adopt a healthy meetings policy to serve nutritious food at business meetings. GMA has also served as an incubator for health and wellness initiatives that are supported by a self-selected and highly motivated group of companies and company leaders that include many GMA members.

For all the interviewees, strong leadership from business or organizational senior management played a key role in community health program support. Ted McGreer, the owner of Ted’s Shoes and Sport, had a history of dedication to community service and health as a member of Rotary Club, the community service organization, and as an avid triathlete. These passions carried into his business once it was launched.

Vitamix CEO Jodi Berg is also a fervent supporter of its community health initiatives, and all business employees carry a vision statement on their work badge to emphasize that they “improve the vitality of people’s lives and liberate the world from conventional food and beverage preparation boundaries” on a daily basis.

In short, businesses strongly feel that the dynamism of a champion and the support of senior management are essential to achieving the goals of community health initiatives.

Types of Programs

Partnering with external organizations was the predominant method for businesses to help improve community health. Such organizations consisted of nonprofit or public sector organizations, trade associations, or local civic organizations, all of which could provide opportunities for businesses or member-based organizations to access existing community health programs.

Among the member-based organizations studied, the community health programs of GPBCH and the Wellness Council are intrinsically oriented toward external partnerships given their missions and organizational structures to serve members in supporting community health. GPBCH is a part of the Philadelphia Health Initiative, a multisector coalition with partners such as the Philadelphia Department of Public Health and STOP Obesity Alliance to prevent obesity and promote healthy weight throughout the community and through workplace programs and policies. As a trade association, GMA joined forces with the Food Marketing Institute to bring consumers Facts Up Front, a voluntary front-of-pack labeling initiative that takes key information directly from the FDA-regulated Nutrition Facts Panel and presents it in a clear, simple, and easy-to-use format on the front of food and beverage packages.

Businesses also have an effect on community health through shared value, using their products and services to address community health issues. The health care industry has a natural inclination to improve community health given its industry focus, but businesses outside the health care industry may also use their products and services to improve community health. Amway, for example, has innovated drinking water treatment technology with its eSpring water filter, integrating ultraviolet disinfection to destroy more than 99.99 percent of the bacteria and viruses commonly found in potable water. Similarly, Texas-based insurance company Higginbotham uses its own company to try out community health programs, such as a tobacco cessation program offered through its county public health department, that the company may eventually recommend to its corporate clients for use in their own wellness programs.

However, shared value and social entrepreneurship are not always paths available to small and medium businesses. Many do not directly engage with consumers as providers of products or services, and others do not have the capacity to change their business models. Instead, most focused on how they could leverage their human capital either internally or externally to promote change in their communities, such as Ted’s Shoes and Sport or Vitamix.

Almost uniformly, businesses were involved in some type of philanthropic giving in community health, through in-kind donations, grant giving, or sponsorship of community health events or organizations. Many large and medium-size businesses have foundations dedicated to philanthropic efforts in community health. Finally, employee volunteerism and, to a lesser extent, participation on the boards or advisory councils of health groups was encouraged.

Measurement and Evaluation (M&E)

Metrics play a valuable role for businesses and their community health programs, but assessing the health outcomes of their programs is challenging for many businesses. All the businesses and member-based organizations interviewed captured narrative data and metrics on participation, the number of units donated and distributed, or similar measurements. Some data collection is more substantial, enabling businesses and member-based organizations to track programs and adjust them when data show that changes may be necessary to improve effect and outcomes.

Some of these data were collected by the businesses themselves; in other instances data were supplied by program partner organizations. The businesses and member-based organizations interviewed do not have dedicated teams or specialists to evaluate programmatic success, so the assessment of health outcomes is limited to situations where a program partner brings that skill set to the collaboration. For example, Jasper Engines partners with an insurance broker that aggregates program data for the business, creates dashboards, and examines data trends over time.

The data, once obtained, are typically used in several ways. On a grand scale, the programmatic data help the business consider the success of a program and potentially whether to partner with a particular organization in the future. Data are also used for corporate citizenship reporting purposes, marketing and other external communications, and, in the case of the member-based organizations, new member recruitment to the organization. And frequently, they are shared with senior management and members to justify the existence of programs and determine the direction of future programming (see Box 5).

Challenges

Several businesses cited differences in work style between the private sector and nonprofit or public sectors as hindering joint efforts on community health programs. Because of differences in pace and bureaucratic hurdles with partners, some businesses and member-based organizations needed to adjust their timelines and expectations when working with the nonprofit or public sectors. Businesses also found that some partners had more capacity to collaborate than others, so vetting was key to determine reliable partners to execute programs.

Alignment of priorities was also mentioned as a challenge. For the member-based organizations whose members may have competing desires, finding a middle ground for a community health program that the majority of stakeholders could agree on was essential. Internal business silos and not having the right people at the table were also mentioned as potential barriers to building strong community health programs. Human resource benefit managers, for instance, may serve as the main business liaison to the member-based organization, but their goals for involvement with the organization may not be aligned with internal corporate affairs or corporate citizenship departments that may be better suited as the main points of contact for initiatives on community health programs.

Adapting to regulations could limit the extent to which businesses could effect change in community health. In one example in a Vitamix program, blenders were donated to local schools to allow them to create healthful smoothies to sell in school cafeterias at a reduced cost for disadvantaged students. The program ran into a roadblock when a regulatory change no longer allowed smoothies to be a reimbursable food item and schools no longer used the blenders as a consequence. Smaller businesses also cited issues such as high business taxes cutting into the amount of funding they can dedicate to community health programs.

Finally, long-term sustainable funding was mentioned as a challenge for small businesses, which have smaller revenue streams, and for member-based organizations, which depend on their membership for income to fund their community health programs.

Lessons Learned

Programmatically, interviewees emphasized the importance of a champion, whether internal or external, in each organization involved in a community health partnership. Strong leadership and vision are required to see programs through and to foster the participation of other organizations. The interviewees also noted that the right stakeholders need to be at the table so that informed decisions could be made efficiently.

Alignment of goals and organizational readiness were also lessons learned. Businesses found that defining actionable programmatic steps with a partner capable of committing the time and effort to the collaboration was essential. For example, with its blender donation program, Vitamix approached schools about their interest in participating in the program but found that quite a few were not prepared to partner. As an alternative, Vitamix established an online application process that defined the criteria for program participation and allowed schools to submit an application when they were ready. The takeaway was that it is sometimes necessary to adjust to the pace of work and other expectations when dealing with partners outside the private sector and unused to working with companies to achieve results.

Communities also need to be ready for business community health programs. The Wellness Council, for example, realized that it needed to slow down its program expansion in larger communities so that it could devote more time to understanding the community health needs in these larger communities and how to best get involved. Recognizing that community dynamics and cultures may differ between communities is crucial to modifying programs quickly to maximize successful implementation.

Ultimately, the businesses and member-based organizations interviewed said that sustaining community health programs is strongly contingent on boards of directors and employee support among businesses. Among the member-based organizations, member support is necessary. Businesses and member-based organizations alike are able to sustain activities if these stakeholders like the programs and see value from them, as shown through measurement and data. Equally important to program sustainability are champions within companies, at partner organizations, and within the communities that they want to improve. Finally, businesses’ continued support of community health is highly contingent on funding and growth in core business activities.

Conclusion

The passion, processes, and types of community health programs that companies engage in do not vary based on their size. Instead, differences in business size have a greater influence on funding and staffing for partnerships. Large and medium-sized businesses have the resources and dedicated staff to lead more numerous or more extensive community health programs. For small businesses such as Ted’s Shoes and Sport, community health programs are fueled by a strong commitment with greater staff involvement.

Local civic organizations and trade associations also play an important role as intermediaries between businesses and communities to improve community health. Large and small businesses alike can benefit from such organizations. The member-based organizations interviewed as well as national groups such as the USCCF’s Health Means Business campaign amplify the voice of businesses and have more influence on community health through access to a broader group of businesses and programs.

More to Learn

This paper adds to the existing literature on community health by exploring the motivations and processes that SMEs and member-based organizations undertake when involved in community health programs. However, it is difficult to extrapolate from this small sample the overall prevalence of SME involvement in community health. A large-scale survey of the SME landscape would be beneficial in this regard.

Many of the businesses investigated had ties to health or nutrition and therefore had a business imperative to become involved in community health programs. Future research may expressly focus on businesses in industries entirely outside of health and nutrition to explore what motivates them to become active in community health.

Findings show that data and metrics are a vital component of any business community health program, but assessing health outcomes is done only occasionally. Previous studies on health metrics in business may provide more guidance to businesses on how to bridge this divide and direction on where to seek assistance from outside organizations on measurement and evaluation [15,23].

Future research may also look at which policies or other public initiatives could be implemented to motivate businesses to extend their well-being and health efforts into communities. Additional regulatory incentives may propel more businesses to action. There are critical reasons for businesses to get involved in community health, and the number of ways to do it with very willing and capable partners is increasing. By taking advantage of these opportunities, businesses have the potential to improve their bottom lines and, more broadly, make a significant contribution to the health of communities.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! New from @theNAMedicine: The ROI of Health & Well-Being: Business Investment in Healthier Communities: http://bit.ly/2zyLA44 #PopHealthRT

Tweet this! New from @theNAMedicine: The ROI of Health & Well-Being: Business Investment in Healthier Communities: http://bit.ly/2zyLA44 #PopHealthRT

![]() Tweet this! An exploration of the business motivation for investing in community health: http://bit.ly/2zyLA44

Tweet this! An exploration of the business motivation for investing in community health: http://bit.ly/2zyLA44 #PopHealthRT

![]() Tweet this! Why businesses are motivated to invest in community health & the challenges they face in doing so: http://bit.ly/2zyLA44 #PopHealthRT

Tweet this! Why businesses are motivated to invest in community health & the challenges they face in doing so: http://bit.ly/2zyLA44 #PopHealthRT

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- Trading Economics. 2017. United States nonfarm labour productivity, 1915-2016. Available at: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/united-states/productivity (accessed August 7, 2017).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. Obesity and overweight. National Center for Health Statistics. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm (accessed August 7, 2017).

- Cawley, J., and C. Meyerhoefer. 2012. The medical care costs of obesity: An instrumental variables approach. Journal of Health Economics 31:219-230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.003

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. Alcohol use. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/alcohol.htm (accessed August 7, 2017).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. The cost of excessive alcohol use. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/images/releases/2015/p1015-excessive-alcohol.pdf (accessed August 7, 2017).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Cigarette Smoking and Electonic Cigarette Use. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/smoking.htm (accessed August 7, 2017).

- Witters, D., and S. Agrawal. 2013. Smoking linked to $278 billion in losses for U.S. employers. Gallup News. September 26. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/164651/smoking-linked-278-billion-losses-employers.aspx (accessed August 7, 2017).

- Depression in the U.S. household population, 2009-2012. National Center for Health Statistics. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db172.htm (accessed August 7, 2017).

- Witters, D., D. Liu, and S. Agrawal. 2013. Depression costs U.S. workplaces $23 billion in absenteeism. Gallup News. July 24. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/163619/depression-costs-workplaces-billion-absenteeism.aspx (accessed August 7, 2017).

- Bloom, D. E., E. T. Caniero, E. Jané-Llopis, S. Abrahams-Gessel, L. R. Bloom, S. Fathima, B. Feigl, T. Gaziano, M. Mowafi, A. Pandya, K. Prettner, L. Rosenberg, B. Seligman, A. Stein, and C. Weinstein. 2011. The global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s18806en/s18806en.pdf.pdf (accessed October 24, 2017).

- The public sector is defined as that portion of an economic system that is controlled by national, state or provincial, and local governments.com. Community health. Available at: http://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/psychology/psychology-and-psychiatry/community-health (accessed August 7, 2017).

- Christakis, N. A., and J. H. Fowler. 2007. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. New England Journal of Medicine 357(4):370-379. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa066082

- Oziransky, V., D. Yach, T. Y. Tsao, A. Luterek, and D. Stevens. 2015. Beyond the four walls: Why community is critical to workforce health. New York: Vitality Institute. Available at: https://www.issuelab.org/resources/22541/22541.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO) Employer-Community Collaboration Committee. 2014. Environmental scan: Role of corporate America in community health and wellness. Paper presented to the Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Washington, DC.

- Quench, J., and E. Boudreau. 2016. Community health. Harvard Business School Case 516- 075, Cambridge, MA, Harvard Business School. Available at: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=50661 (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Pronk, N., C. Baase, J. Noyce, and D. Stevens. 2015. Corporate America and community health: Exploring the business case for investment. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine 57(5):493-500. https://doi.org/10.1097/jom.0000000000000431

-

Institute of Medicine. 2015. Business Engagement in Building Healthy Communities: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/19003

- Fujiwara, T., and I. Kawachi. 2008. Social capital and health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35(2):39-144. Available at: http://www.midus.wisc.edu/findings/pdfs/742.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Porter, M., and M. Kramer. 2011. Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value# (accessed August 7, 2017).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Applying a Health Lens to Business Practices, Policies, and Investments: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21842

- Small Business Majority. 2014. Small business attitudes on wellness programs. Washington, DC: Small Business Majority. Available at: http://www.smallbusinessmajority.org/sites/default/files/research-reports/072114-Small-Business-and-Wellness.pdf (accessed August 7, 2017).

- Malan, D., S. Radjy, N. Pronk, and D. Yach. Reporting on health: A roadmap for investors, companies, and reporting platforms. New York: Vitality Institute. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292148019_Reporting_on_Health_A_Roadmap_for_Investors_Companies_and_Reporting_Platforms (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Berry, L. L., A. M. Mirabito, and W. Baun. 2010. What’s the hard return on employee wellness programs? Harvard Business Review 88(12):104-112. Available at: https://hbr.org/2010/12/whats-the-hard-return-on-employee-wellness-programs (accessed September 1, 2020).