Public Deliberation in Service to Health Equity: Investing Resources in Roanoke, Virginia

Introduction

This paper describes how members of the city planning department of Roanoke, Virginia, used public deliberation to incorporate community views into local government decision making, in service to health equity. The authors present an overview of public deliberation and the specifics of this case study, including motivations, methods, and outcomes.

Increased efforts have been made to engage community members in health and health care decision making processes. Public deliberation is one method used to this end, specifically when there is a value-laden issue that cannot be decided through technical solutions alone [1]. Public deliberation solicits input from a cross-section of informed participants who will be affected by a decision and provides the deliberation sponsor with thoughtful reflections of constituent values and priorities.

In conducting a public deliberation, a decision maker engages a neutral third party to develop guidance and facilitate the process, which includes the following:

- crafting an overarching question, in consultation with the sponsor;

- designing a series of educational activities and facilitated discussions that move the conversation toward an understanding of participants’ priorities on the topic;

- engaging a diverse group of participants; and

- presenting unbiased educational information.

The deliberative question (or questions) provides the structure for the activity. Most commonly, the question is framed to allow participants to give close-ended guidance to the sponsor with respect to an option or options that are prioritized by participants. Equally important, however, is capturing participants’ reasons and rationale for their views. Ideally, the question offers options that can be thoughtfully considered by participants and that are realistic enough to incorporate into future actions.

A public deliberation is distinct from other methods of community engagement in three fundamental ways: (1) participants are presented with relevant unbiased educational information that provides a shared knowledge base to draw from, (2) participants engage in a series of discussions focused on the educational information to explore individual and group values and underlying beliefs, and (3) participants make a specific recommendation or recommendations to the sponsor. The facilitated discussions are intended to move participants toward answers that are most reflective of the priorities of the communities they represent. Public deliberations typically range from one to several days in length. Longer deliberations have been shown to increase knowledge gained and to demonstrate greater shifts in participant perspectives [2].

Roanoke Case Study

In 2018, the Roanoke City planning department, working with ChangeLab Solutions, enlisted The New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM) to plan and facilitate a one-day public deliberation to help identify which Roanoke neighborhoods should gain priority for Housing and Urban Development (HUD) community development funding. As part of their work in Roanoke, ChangeLab Solutions, a nonprofit organization focused on advancing equitable laws and policies to promote healthy lives for all, provided equity-focused legal and policy technical assistance to the city and its partners. In deciding where funds would best be used, the planning department was interested in incorporating a focus on health equity within its planning efforts and sought an approach that would meaningfully engage the public in shared decision making. The members of the city planning department chose a public deliberation that incorporated health expertise and used a health lens to reinforce their focus on these values.

Methods for Roanoke Deliberation

Based on the city planning department’s desire to identify high priority neighborhoods as an outcome of the deliberation, NYAM staff proposed two deliberative questions. The first question was, “What information is important to consider and prioritize when identifying which Roanoke neighborhood will receive concentrated HUD community development funding?” and was asked to stimulate reflection and debate. In previous HUD grant cycles, planners had applied an algorithm that identified neighborhoods for investment based on values they assigned to various demographic and community characteristics. This first question was intended to explore the degree to which community and planner values were aligned, and to capture areas unaccounted for in previous decision making. The second question asked participants to narrow the six specific neighborhoods eligible for HUD funding to three.

Following development of the deliberative questions, the Roanoke City planning department began recruitment. The deliberation was held on a weekend to allow participation from individuals who have traditional Monday through Friday work schedules. The sample pool of potential participants included individuals who had previously engaged with various processes to solicit community involvement in the comprehensive planning process.

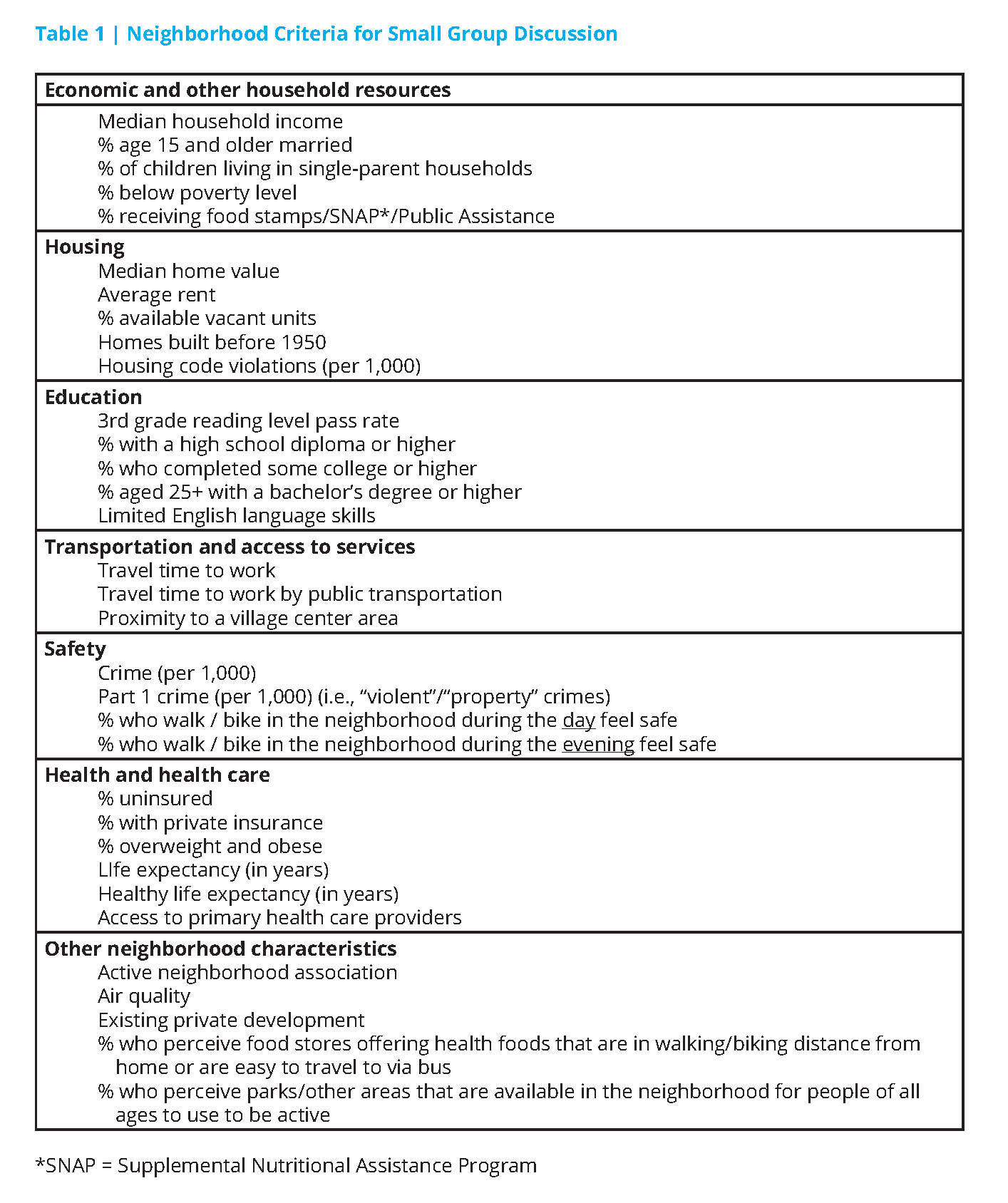

In parallel, NYAM identified and engaged content experts, both within and outside of the Roanoke City planning department, to develop the educational materials that would be presented to participants. Topics included the impact of social and environmental factors on health and health equity, indicators thereof, the history of HUD funding in Roanoke, and criteria used in the past to assess neighborhood-level need and readiness to receive HUD funding. The NYAM team developed large and small group facilitators’ guides to help participants connect their own lived experience and knowledge with the educational information, consider how each aligned with the other, and identify how opinions of their fellow participants impacted their own views, if at all. For the first question, a list of criteria for assessing neighborhood health was developed by incorporating indicators historically used by the planning department that were supplemented with other measures associated with life expectancy (see Table 1) [3].

The public deliberation was facilitated by staff from NYAM and ChangeLab Solutions. Participants were given opportunities to consider criteria to prioritize and neighborhoods to choose in large and small group settings, and on their own, repeatedly throughout the public deliberation. This iterative process allowed participants to identify choices as part of a group, which were then presented and explained to others, while retaining opportunity for individual voting.

Deliberation Findings

After screening, Roanoke recruited 23 people diverse with respect to race, age, and years spent living in Roanoke, but less so regarding other characteristics. Participants were primarily female (68 percent), had some post-high school education (91 percent), and lived in the northwestern quadrant of Roanoke (49 percent). Of those who indicated race/ethnicity, 45 percent were White/Caucasian, 41 percent were Black or African American, and 5 percent were Hispanic/Latino.

Top Criteria

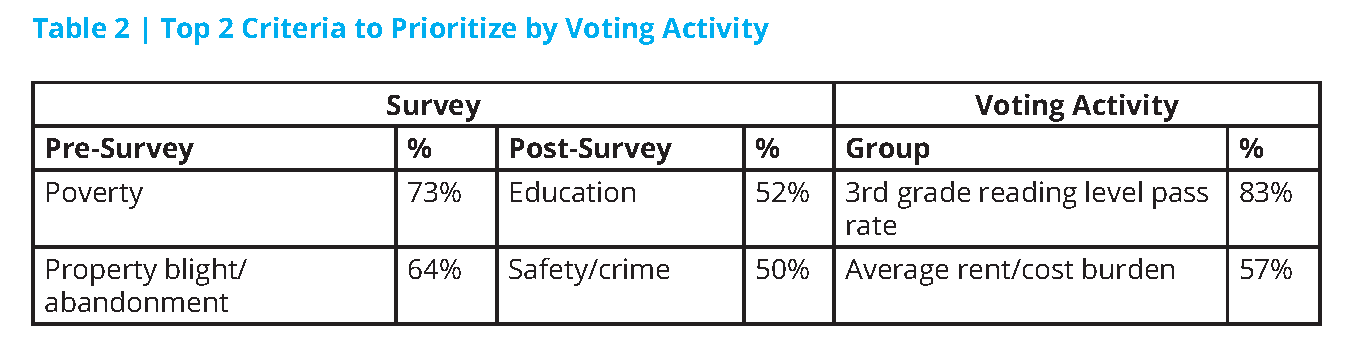

Group voting was conducted at the end of the deliberation (see Table 2), and the individuals surveyed noted that the city planning department should consider following two criteria when determining which neighborhoods receive HUD funding: how many individuals can read at a third-grade level (83 percent) and average rent and associated cost burden (57 percent). Individual selections from the pre- and post-survey noted changes over time; pre-event survey responses showed poverty (73 percent) and property blight/abandonment (64 percent) as the most frequent criteria to prioritize as compared to education (52 percent) and safety/crime (50 percent) in the post-event surveys. During the public deliberation, participants’ choices made in a group were different from those made on their own, suggesting that decisions made in public are more likely to represent an acknowledgment of the experiences and views of other participants.

Neighborhood Selection

Participants in the voting activity as well as the post-surveys selected neighborhood “X.” Roanoke planners used output from the public deliberation to inform their final decision regarding funding and ultimately selected neighborhood “Y” because of the opportunities and readiness exemplified by a strong neighborhood organization that could partner with the planning department in community development efforts. Although participants in the deliberation chose neighborhood “X” as the neighborhood that should receive highest priority, planners viewed a lack of organizational infrastructure as an impediment to immediate gains from HUD investments. However, it was decided that neighborhood “X” would receive investment during the next funding cycle and that planners would provide its neighborhood association with additional support to help build greater community capacity and improve its readiness to be the next target neighborhood.

After the public deliberation, two additional groups convened to consider the next target neighborhood. One group, comprised of internal community development professionals, studied the data and narrowed the selection to neighborhoods “X” and “Y” (the same as the public deliberation group). The next group, comprised of external community development professionals and community organization representatives, selected neighborhood “Y.” The tipping point in favor of neighborhood “Y” was the readiness of the community to engage with the city in the community development effort. For the same reason, the representative from neighborhood “X” advocated the selection of neighborhood “Y” and indicated more time would be used to build capacity of the community organizations operating in the neighborhood.

Discussion

The commitment to engaging community members in the decision-making process, shared by the participants, staff, and leadership of the Roanoke City planning department, set the stage for meaningful conversation and debate about community investments to improve health equity and well-being in the city of Roanoke. Shifts in perspective during the deliberation suggest that individuals were open to new perspectives and differing opinions. Specifically, increased prioritization of education, safety, and crime in the post-event surveys suggests that participants developed a more nuanced understanding of neighborhood characteristics and the factors contributing to neighborhood strength, poverty, and city inequities.

There are few opportunities in which institutions are comfortable providing their constituents with set options to choose from and then commit to following that recommendation [4]. Furthermore, concerns regarding the practicality and validity of public deliberation have been raised, including the necessary resources for planning and implementation, the representativeness of the participants, and the potential for individuals within any group to distort the output of the process.

In assessing the limitations of the Roanoke deliberation, both sponsors and developers were concerned that the meeting’s length (one day) was too brief to build confidence that participants’ underlying values and reasoning were fully explored. While there was agreement that the deliberative format allowed for greater understanding of community views than did typical community meetings, participants were provided a lot of unfamiliar information with relatively little time to process and consider. For example, it proved difficult to limit the list of indicators participants might consider and the final list, as shown in Table 1, is quite lengthy. The specificity of the first question, which asked for prioritization of indicators with different implications for the health of communities, raised questions about whether participants would have changed given more time for debate and reflection. Similarly, both planners and NYAM staff viewed the application of those indicators to decisions regarding the six communities as an overly ambitious task.

Another limitation for this deliberation was the makeup of the participants. Despite Roanoke’s concerted outreach efforts, the individuals who participated in the public deliberation were predominantly female, had higher levels of formal education, and were likely to be from a particular quadrant of the city. Deliberations benefit from a diversity of participants. Offering honorariums that offset potentially lost earnings, holding deliberations on weekends, and offering childcare are methods of attracting participants from a broader range of backgrounds. While fulfilling the first two suggestions, recruiting a representative sample was still difficult.

Conclusion

Despite a growing interest in incorporating community values into actions that affect their constituents, institutional decisions are most commonly dictated by technical and/or political contexts and priorities. It is rare that decision makers view the path forward as best determined by the perspectives and values of the individuals who will feel the impact of a decision. Roanoke City planners were unusual in offering their residents the opportunity to reflect on neighborhood health and well-being and make recommendations on community development investments. The neighborhood that gained the highest support for HUD funding was not selected for immediate investment, but planners have committed to working with that community to prepare it for becoming the recipient in the next round of funding.

The best way to engage community members in planning decisions that lessen inequities in the health of communities remains an open question [5]. Public deliberation is an intriguing approach because of its potential to reimagine the dynamics between those making a decision and those feeling its impact. Public deliberations focus a considerable amount of time on the educational content presented to participants, allowing them greater insight into the various factors weighing on the decision. With this emphasis on knowledge sharing, public deliberation can make community views central to main decisions. Providing an educational component for participants builds on the knowledge base of participants’ own experiences and serves to equalize expertise between participants and sponsor. With time to process and engage with perspectives of others whose life experiences may differ widely, the process provides participants and sponsors alike with multidimensional insight into what people value in shaping the health and well-being of their communities and centers the experiences of participants in a decision. In this instance, public deliberation was used to build on one of the tenets of planning by engaging those with an expertise in health, in service of equity.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! Public deliberation is a promising approach toward ensuring that community priorities and views are integrated into health and health care decision-making. A new #NAMPerspectives reviews how this approach was utilized in Roanoke, VA: https://doi.org/10.31478/202008d

Tweet this! Public deliberation is a promising approach toward ensuring that community priorities and views are integrated into health and health care decision-making. A new #NAMPerspectives reviews how this approach was utilized in Roanoke, VA: https://doi.org/10.31478/202008d

![]() Tweet this! Facilitated discussions and targeted education for community members can help them identify answers that are reflective of their priorities. A new #NAMPerspectives reviews how they utilized public deliberation for decision-making in Roanoke, VA: https://doi.org/10.31478/202008d

Tweet this! Facilitated discussions and targeted education for community members can help them identify answers that are reflective of their priorities. A new #NAMPerspectives reviews how they utilized public deliberation for decision-making in Roanoke, VA: https://doi.org/10.31478/202008d

![]() Tweet this! The best way to engage individuals in decisions that could lessen inequities in the health of their community remains an open question, but public deliberation and facilitated discussion show promise. A new #NAMPerspectives reviews one approach: https://doi.org/10.31478/202008d

Tweet this! The best way to engage individuals in decisions that could lessen inequities in the health of their community remains an open question, but public deliberation and facilitated discussion show promise. A new #NAMPerspectives reviews one approach: https://doi.org/10.31478/202008d

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- Solomon, S., and J. Abelson. 2012. Why and When Should We Use Public Deliberation? Hastings Center Report 42(2):17–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.27

- Carman, K. L., C. Mallery, M. Maurer, G. Wang, S. Garfinkel, M. Yang, D. Gilmore, A. Windham, M. Ginsburg, S. Sofaer, M. Gold, E. Pathak-Sen, T. Davies, J. Siegel, R. Mangrum, J. Fernandez, J. Richmond, J. Fishkin, and A. S. Chao. 2015. Effectiveness of public deliberation methods for gathering input on issues in healthcare: Results from a randomized trial. Social Science & Medicine 133:11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.024

- Woolf, S., D. Chapman, L. Hill, H. Schoomaker, D. Wheeler, L. Snellings, and J. H. Lee. 2018. Uneven opportunities. How conditions for wellness vary across the metropolitan Washington Region. Virginia Commonwealth University Center on Society and Health. Available at: https://www.mwcog.org/documents/2020/10/26/uneven-opportunities-how-conditions-for-wellness-vary-across-the-metropolitan-washington-region-health-health-data/

(accessed July 27, 2020). - Degeling, C., S. M. Carter, and L. Rychetnik. 2015. Which public and why deliberate?—A scoping review of public deliberation in public health and health policy research. Social Science & Medicine 131:114–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.009

- O’Mara-Eves, A., G. Brunton, D. McDaid, S. Oliver, J. Kavanagh, F. Jamal, T. Matosevic, A. Harden, and J. Thomas. 2013. Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: A systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Public Health Research 1(4). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK262817/ (accessed July 27, 2020).