Promoting Well-being in Psychology Graduate Students at the Individual and Systems Levels

TW: suicide

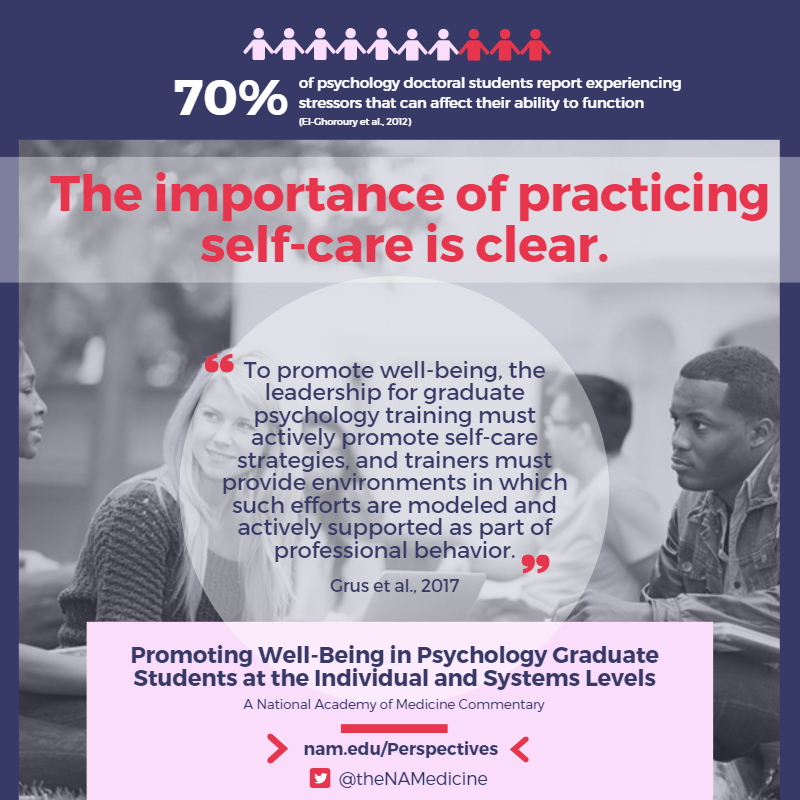

More than 70 percent of psychology doctoral students report experiencing stressors that can affect their ability to fully function (El-Ghoroury et al., 2012). Common stressors include academic responsibilities, debt, anxiety, and poor work-life balance (El-Ghoroury et al., 2012; Kersting et al., 2015). Lack of support from faculty, poor relationships with faculty, and cohort tension are sources of stress and negatively affect both personal and professional functioning while serving as barriers to effective coping (Kersting et al., 2015; Pakenham and Stafford-Brown, 2012). This can result in trainees who have difficulty developing and exhibiting the proper degree of professional competence (termed as problems with professional competence; Forrest et al., 1999; Smith and Moss, 2009). These problems with professional competence can be manifested in difficulties attaining identity as a psychologist, self-awareness, and reliable clinical judgment and reflection skills, as well as developing the ability to have effective interpersonal interactions (Elman and Forrest, 2007). Once competency problems emerge, they demand immediate attention in order to ensure patient safety and effective care. A proactive and preventive strategy involves implementing both individual- and systems-level approaches designed to increase self-care.

The importance of practicing self-care is clear. At the individual level, graduate students who engage in self-care activities (e.g., seek social support, exercise, practice mindfulness, and use adaptive emotional regulation strategies) experience more benefits than those who do not engage in self-care (Colman et al., 2016; Myers et al., 2012; Shapiro et al., 2007). Positive benefits include decreased psychological distress and increased life satisfaction. Unfortunately, regular self-care is easier said than done, especially for students.

Despite its role as one of the core aspects of competency in psychology, self-care is not formally addressed or actively taught by most training programs (Bamonti et al., 2014; Wise et al., 2012), and the literature on systems-level best practices for self-care is limited. This is unfortunate given that program cultures that do not support self-care (e.g., faculty who model working at all hours and “living to work,” or trainers or peers providing visible rewards for work-life imbalance) may discourage student self-care, despite verbal messages that encourage it. Although the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (APA, 2017) clearly states that one must take steps to resolve difficulties that affect professional functioning, students may not have the skills to identify their own stress or to implement adaptive self-care strategies. Indeed, psychology graduate students often report that their training programs do not offer written materials on self-care or stress (82.2 percent), do not sponsor self-care activities (63.4 percent), or do not informally promote an atmosphere of self-care (59.3 percent) (Munsey, 2006). As members of a system in which the neglect of self-care may be modeled, students may hesitate to be open and seek help. Complicating this, practicing psychologists (including trainers) often hesitate to take active steps to remediate competence problems, perhaps due to concerns regarding the actions that might be taken by state regulatory boards if such problems are disclosed (O’Connor, 2001; Van Horne, 2004). In previous studies, psychologists have identified a lack of time, privacy concerns, not knowing about available resources, and shame, guilt, or embarrassment as primary obstacles to self-care (ACCA, 2009; Bridgeman and Galper, 2010).

To promote well-being, the leadership for graduate psychology training must actively promote self-care strategies, and trainers must provide environments in which such efforts are modeled and actively supported as part of professional behavior. Fortunately, there are encouraging signs of change in this direction. Attention has been paid to the value of integrating into training environments a culture of self-care within that stresses the acquisition of the requisite competencies to manage the stress of graduate training and a career as a psychologist (Barnett et al., 2007). Psychologists have been encouraged to develop a “competent community” on the premise that ensuring the competence of individual professionals is both an individual and community responsibility (Johnson et al., 2012). In a competent community, groups of psychologists foster one another’s ability to fully function in their practices and to address it and offer support when a competence problem is observed. Introducing trainees to this community-focused approach to well-being can benefit them during training, can foster a lifelong commitment to self-care as a stress management strategy, and can establish a culture that values self-care as an ethical competency (Barnett et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2012).

In addition, the American Psychological Association’s Commission on Accreditation has adopted new standards that require programs to document how they provide students with opportunities to develop competencies in the domain of professional values and attitudes—such as self-reflection regarding personal and professional functioning, attending to one’s professional well-being, and effectiveness (APA Commission on Accreditation, 2015). It has been suggested that programs should provide seminars educating students on self-care behaviors, address self-care and professional competence in practicum meetings and other training forums, create self-care activities in the program for students and faculty alike, establish student support groups, and encourage personal psychotherapy (Carter and Barnett, 2014). Additionally, recommendations have been made regarding the importance of creating departmental self-care committees composed of both trainers and students that are responsible for evaluating the self-care needs of the students and organizing activities (Myers et al., 2012).

Other suggestions that might be incorporated to address well-being at a systems level in psychology students as well as in learners from other professions include:

- Acknowledging the intensity and stress that accompany graduate study and offer guidance to trainees, including a recommendation to invest in one’s health as stress management (Mattu, 2011).

- Connecting self-care to professional competence in order to emphasize the necessity of monitoring and addressing stress before it affects personal and professional functioning.

- Addressing self-care in handbooks that are given out prior to program entry, highlighting it regularly throughout the program, providing resources that allow individuals to more easily engage in self-care behaviors (e.g., psychotherapist referrals, mindfulness-based stress reduction training), and monitoring program culture (e.g., comments, even in jest, about giving one’s life to the program).

- Including maintaining self as a healthy professional into formal program goals or objectives and tying this ideal to those standards by which programs are evaluated.

- Incorporating discussions of competence within a professional issues course required of all 1st-year students.

- Supporting the development of a “competent community” for students during graduate training.

Graduate training in psychology can create stress in students. Given the power dynamics associated with student status, it is incumbent on programs and the profession to create resources and cultures that support student well-being. Arguably, as a profession dedicated to promoting health and well-being, psychology should be a leader in this regard.

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- ACCA (Advisory Committee on Colleague Assistance). 2009. Who cares? Barriers, benefits and resources in colleague assistance and self-care. Paper presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, Toronto, ON.

- APA (American Psychological Association). 2017. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Available at: http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx (accessed January 24, 2017).

- APA Commission on Accreditation. 2015. Standards of accreditation in health service psychology. Available at: http://www.apa.org/ed/accreditation/about/policies/standardsof-accreditation.pdf (accessed January 24, 2017).

- Bamonti, P. M., C. M. Keelan, N. Larson, J. M. Mentrikoski, C. L. Randall, S. K. Sly, R. M. Travers, and D. W. McNeil. 2014. Promoting ethical behavior by cultivating a culture of self-care during graduate training: A call to action. Training and Education in Professional Psychology 8(4):253–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000056

- Barnett, J. E., E. K. Baker, N. S. Elman, and G. R. Schoener. 2007. In pursuit of wellness: The self-care imperative. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 38(6):603–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.6.603

- Bridgeman, D., and D. Galper. 2010. Listening to our colleagues: 2009 practice survey. Worries, wellness, & wisdom. Paper presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, San Diego, CA.

- Carter, L. A., and J. E. Barnett. 2014. Self-care for clinicians in training: A guide to psychological wellness for graduate students in psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Colman, D. E., R. Echon, M. S. Lemay, J. McDonald, K. R. Smith, J. Spencer, and J. K. Swift. 2016. The efficacy of self-care for graduate students in professional psychology: A meta-analysis. Training and Education in Professional Psychology 10(4):188–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000130

- El-Ghoroury, N. H., D. I. Galper, A. Sawaqdeh, and L. F. Bufka. 2012. Stress, coping, and barriers to wellness among psychology graduate students. Training and Education in Professional Psychology 6(2):122–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028768

- Elman, N. S., and L. Forrest. 2007. From trainee impairment to professional competence problems: Seeking new terminology that facilitates effective action. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 38(5):501–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.5.501

- Forrest, L., N. Elman, S. Gizara, and T. Vacha-Haase. 1999. Trainee impairment. The Counseling Psychologist 27(5):627–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000099275001

- Johnson, W. B., J. E. Barnett, N. S. Elman, L. Forrest, and N. J. Kaslow. 2012. The competent community: Toward a vital reformulation of professional ethics. American Psychologist 67(7):557–569. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027206

- Kersting, H., A. Gorzynski, and N. Chapman. 2015. How to beat the stress: Psychology graduate students adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies. Psychotherapy Bulletin 50(4):55–58. Available at: https://societyforpsychotherapy.org/how-to-beat-the-psychology-graduate-student-stress/ (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Mattu, A. 2011. Secrets for grad school success. Available at: http://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2011/09/corner.aspx (accessed November 17, 2016).

- Munsey, C. 2006. Questions of balance: An APA survey finds a lack of attention to self-care among training programs. Available at: http://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2006/11/cover-balance.aspx (accessed January 24, 2017).

- Myers, S. B., A. C. Sweeney, V. Popick, K. Wesley, A. Bordfeld, and R. Fingerhut. 2012. Self-care practices and perceived stress levels among psychology graduate students. Training and Education in Professional Psychology 6(1):55–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026534

- O’Connor, M. F. 2001. On the etiology and effective management of professional distress and impairment among psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 32(4):345–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.32.4.345

- Pakenham, K. I., and J. Stafford-Brown. 2012. Stress in clinical psychology trainees: Current research status and future directions. Australian Psychologist 47(3):147–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2012.00070.x

- Shapiro, S. L., K. W. Brown, and G. M. Biegel. 2007. Teaching self-care to caregivers: Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology 1(2):105–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3918.1.2.105

- Smith, P. L., and S. B. Moss. 2009. Psychologist impairment: What is it, how can it be prevented, and what can be done to address it? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 16(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01137.x

- Van Horne, B. A. 2004. Psychology licensing board disciplinary actions: The realities. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 35(2):170–178. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.35.2.170

- Wise, E. H., M. A. Hersh, and C. M. Gibson. 2012. Ethics, self-care and well-being for psychologists: Reenvisioning the stress-distress continuum. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 43(5):487–494. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029446