Preparing for Better Health and Health Care for an Aging Population: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

Introduction

The proportion of the US population over 65 years old is increasing dramatically, and the group over 85 years old, the “oldest old,” is the most rapidly growing segment. People who survive into higher ages in America, which itself is an aging society, face a suite of competing forces that will yield healthy life extension for some and life extension accompanied by notable increases in frailty and disability for many. We spend more, for worse outcomes, than many if not all other developed countries, including care for older persons. Looking forward, our health care system is unprepared to provide the medical and support services needed for previously unimagined numbers of sick older persons, and we are not investing in keeping people healthy into their highest ages. This paper summarizes the opportunities for valuable policy advances in several important spheres that are central to the health and well being of older persons. In all of them, concerns regarding disparities in health and the severe concentration of risk among the poorest and least educated members of our society present special opportunities for progress and these issues are addressed in detail in other papers in the Vital Directions series.

Key Trends in Demography and Health Equity in the 21st Century

Aging and health intersect both at the level of the individual and at the level of the entire society. For individuals, the extension of life achieved in the last century as a product of advances in public health, socioeconomic development, and medical technology constitutes a monumental achievement for humanity. Most people born today will live past the age of 65 years, and many will survive past the age of 85 years, but life extension comes with a Faustian trade. Modern medical advances will no doubt endure, but it is possible that continued success in attacking fatal diseases could expose the saved population to a higher risk of extreme frailty and disability as disabling diseases accumulate in aging bodies.

The aging of our society, reflecting the rapidly increasing proportion of older people relative to the rest of the population, is a product of two major demographic events: the substantial increase in life expectancy and the baby boom. At the societal level, this population shift will place great pressure on our fragile systems of health care, public health, and other supports for older persons. Past increases in life expectancy are impressive, but the more recent news is not as good in America. In the middle 1980s, life expectancy of women in the United States was about the average of that in Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. Since 2000, we have ranked last, and the gap between the United States and other OECD countries in health status is also widening. Contributors to the absolute increases in poor health experienced by the most disadvantaged Americans, the poor and less educated, include the concentration in these groups of multiple risk factors, including smoking, obesity, gun violence, and increased teenage pregnancy (NASEM, 2015; NRC, 2012; Schroeder, 2016).

As America ages, it becomes more diverse. By 2030, the non-Hispanic white population will be the numerical minority in the United States. Increased longevity is prevalent among several ethnic and racial groups (such as black, Chinese, Japanese, Cuban, and Mexican American). Younger Hispanics, the most rapidly growing group in our population, are generally US-born and have both higher fertility rates and much higher disability rates than older Hispanics, who are more likely to be foreign-born.

As discussed in detail in other discussion papers in the Vital Directions series, owing largely to socioeconomic factors, many racial and ethnic groups, especially blacks, are at disproportionate risk for adverse health outcomes over the life course compared with whites. Many factors may contribute to the disparity, including biologic disposition to dietary and lifestyle behaviors and failure to receive adequate health care. Given complex sociohistorical contexts, comparisons between racial and ethnic groups may be less useful than comparisons among people within groups—for example, according to socioeconomic status (SES)—in uncovering specific mechanisms.

SES-based racial and ethnic-group disparities exist in both physical and mental well-being, even where access to health care is equal. Although targeted policy considerations regarding disparities are not provided here, it is important to understand that disparities constitute an important target for improvements in each of the key areas we identify for action. Issues of health disparity are addressed more specifically in the Vital Directions Perspective on addressing health disparities and the social determinants of health (Adler et al., 2016).

Key Opportunities for Progress

Enhancing Delivery of Effective Care for Those Who Have Multiple Chronic Conditions

The health care needs of older adults coping with multiple chronic conditions, which account for a vast majority of Medicare expenditures, are poorly managed (MedPAC, 2014). Effective management that engages older adults, family caregivers, and clinicians in collaboratively identifying patients’ needs and goals and in implementing individualized care plans is essential to achieve higher-value health care. Evidence-based approaches to care management are available, but the uptake and spread of most models have been sporadic and slow.

Many effective approaches to enhancing delivery of care for older persons have been developed; the problems have generally been in dissemination and implementation, often owing to lack of funding. Examples of such programs are the following:

- Care options in varied settings: the Transitional Care Model (TCM). The TCM is an advanced-practice, nurse-coordinated team-based care model that targets at-risk community-based older adults who have multiple chronic conditions and their family caregivers. In several clinical trials funded by the National Institutes of Health, the TCM has consistently demonstrated improvements in patients’ care experiences, health, and quality-of-life outcomes while decreasing total health care costs (Naylor et al., 2004).

- Care options in nursing homes: the Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) program. The INTERACT program includes a variety of communication, decision-support, advance care planning and quality-improvement tools, all designed to support nursing-home staff efforts to prevent avoidable rehospitalizations of residents. In a typical 100-bed nursing home, the INTERACT program was estimated to reduce rehospitalizations by an average of 25 per year for a net savings of $117,000 per facility (Ouslander et al., 2011).

- Care options in the community: home-based primary care. Programs that deliver team-based primary care in the home for people who have advancing chronic conditions have been shown to be very effective by the Department of Veterans Affairs and in a Medicare demonstration (Independence at Home).

Delivery-of-Care Policy Alternatives

- Widespread adoption of high-value, rigorously evidence-based best practices with demonstrated longer-term value that target older adults, such as those listed above (Naylor et al., 2014), should be encouraged. Resources now targeted to short-term results for older adults who have multiple chronic conditions, such as those focused on reducing 30- day rehospitalizations, should be redirected to longer-term solutions that align closely with the needs and preferences of this population.

- New models of care for older adults in such neglected areas as prevention, long-term care, and palliative care should be developed.

- The Public Health Service should strengthen its efforts, such as the “Healthy People” program, to foster a prevention and health-promotion agenda for longer lives with a deep grounding in socioeconomic determinants of health.

- Robust metrics of effective care management for vulnerable older adults should be developed with emphasis on outcomes that matter to patients and their family caregivers.

Strengthening the Elder Care Workforce

One of the greatest challenges to the capacity of our health care system to deliver needed high-quality services to the growing elderly population resides in the current and likely future inadequacy of our workforce, including both the numbers of workers and the quality of their training.

The Institute of Medicine, now the National Academy of Medicine, drew attention to this issue first in 1978 (IOM, 1978), again in 1987 (Rowe et al., 1987), and more recently in its 2008 report, Retooling for an Aging America, which reported an in-depth analysis of the future demand for and the recruitment and retention challenges surrounding all components of the geriatric health care workforce. Despite increased awareness of the impending workforce crisis, the problems persist almost a decade later.

The Professional Health Care Workforce

We have an alarming dearth of adequately prepared geriatricians, nurses, social workers, and public health professionals. The number of board-certified geriatricians, estimated at 7,500, is less than half the estimated need, and the pipeline of geriatricians in training is grossly inadequate. The reasons are many, but a prominent impediment is the substantial financial disadvantage facing geriatricians. Working in fee-for-service systems, which continue to dominate health care payment, internists or family physicians who complete additional training to become geriatricians can expect substantial decreases in their income despite their enhanced expertise. The reason for this is that the care they provide is more time-intensive and all their patients will be on Medicare or on Medicare and Medicaid simultaneously (“dual users”), as opposed to the mix of Medicare and commercially insured patients served by most general physicians. The failure of Medicare to acknowledge the value of the enhanced expertise punishes those dedicated to careers in serving the elderly (IOM, 2008). Approaches are needed not only in the fee-for-service system that accounts for most of Medicare but in increasingly important population-based approaches such as accountable care organizations (ACOs).

Nursing is also deficient in geriatrics. Fewer than 1% of registered nurses and fewer than 3% of advanced practice registered nurses are certified in geriatrics. One of the major impediments for nurses is related to the lack of sufficiently trained faculty in geriatric nursing. The same can be said of pharmacists, physical therapists, social workers, occupational therapists, and the full array of allied health disciplines (IOM, 2008).

Besides the insufficient numbers, there is a growing awareness that the greater problem—which may be amenable to more rapid improvement if appropriate policies are put into place—is the lack of sufficient training and competence of all physicians and nurses who treat older patients in the diagnosis and management of common geriatric problems. This issue of geriatric competence of all health care providers may be the number one problem we face in delivering needed care for older persons.

An additional critically important issue is related to the lack of effective coordination of specialists such as geriatricians with primary care providers. Such lack of coordination seems worst in traditional fee-for-service settings and may be less severe in population-based settings, such as ACOs.

Direct Care Workers

Direct care workers—certified nursing assistants (CNAs), home health aides, and home care and personal care aides (1.4 million in 2012)—provide an estimated 70–80% of the paid hands-on care to older adults in nursing homes, assisted-living homes, and other home- and community-based settings (Eldercare Workforce Alliance, 2014). From 2010 to 2020, available jobs in those occupations are expected to grow by 48% (in contrast with all occupational growth of just 14%) at the same time that the availability of people most likely to fill the occupations is projected to decline (Stone, 2015).

Recruiting and retaining competent, stable direct care workers are serious problems in many communities around the country. Turnover rates are above 50%. Many factors contribute to the turnover, but two major issues are low wages (median hourly wages of CNAs, home health aides, and personal care workers in 2014 were $12.06, $10.28, and $9.83, respectively) (BLS, no date a, b, c) and inadequate training and supervision. Federal regulations require CNAs and home health aides employed by Medicare- or Medicaid-certified organizations to have at least 75 hours of training; that is less than some states require for crossing guards and dog groomers! There are no federal training requirements for home care and personal care workers.

An important issue related to both the professional and the direct elder care components of the workforce is ensuring competence in the recognition, prevention, and management of elder abuse and neglect—a problem that may be especially critical in underprivileged populations.

Workforce Policy Alternatives

Enhancing Geriatric Competence—Priority Considerations

- Physician and nurse training in all settings where older adults receive care, including nursing homes, assisted-living facilities, and patients’ homes.

- Demonstration of competence in the care of older adults as a criterion for all licensure, certification, and maintenance of certification for health care professionals.

- Federal requirements for training of at least 120 hours for CNAs and home health aides and demonstration of competence in the care of older adults as a criterion for certification. States should also establish minimum training requirements for personal care aides.

- Incorporation by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) of direct care workers into team-based approaches to caring for chronically disabled older adults.

Increasing Recruitment and Retention—Priority Considerations

- Public and private payers providing financial incentives to increase the number of geriatric specialists in all health professions.

- CMS extending graduate medical education payments to cover costs of residency training to public health physicians and nurses to support their training in geriatric care and health promotion.

- All payers including a specific enhancement of reimbursement for clinical services delivered to older adults by practitioners who have a certification of special expertise in geriatrics.

- The direct care workforce being adequately compensated with a living wage commensurate with the skills and knowledge required to perform high-quality work.

- States and the federal government instituting programs for loan forgiveness, scholarships, and direct financial incentives for professionals who become geriatric specialists. One such mechanism should include the development of a National Geriatric Service Corps, modeled after the National Health Service Corps.

- The Department of Labor and the Department of Health and Human Services (specifically, CMS and the Health Resources and Services Administration) developing apprenticeship opportunities for direct care workers in the whole array of long-term support and service settings.

Social Engagement and Work-Related Strategies to Enhance Health in Late Life

It is now widely accepted that social factors play an important role in determining health status. As mentioned previously, the issues of social determinants of health status are addressed in detail in other discussion papers in the Vital Directions series. Nonetheless, one aspect of particular importance to older persons deserves attention here. A vast body of research indicates that the degree to which men and women are “connected” to others, including volunteerism and work for pay, is an important determinant of their well-being.

Engagement

The effect of deficient social networks and relationships on mortality is similar to that of other well-identified medical and behavioral risk factors. Conversely, social engagement—through friends, family, volunteering, or continuing to work—has many physical and mental benefits.

Over the last 15–20 years, older people have become more isolated and new cohorts of middle-aged adults, especially those 55–64 years old, have shown a major drop in engagement. In addition, national volunteer efforts—such as Foster Grandparents program, the Retired and Senior Volunteer Program (RSVP), and the Senior Companions program—reach only a small percentage of the eligible target audience and have long waiting lists. Programs with high impact on the volunteers and recipients, such as the Experience Corps, have an inadequate number of high-impact opportunities because of low financing.

Work

An impressive and growing body of evidence suggests that working is health promoting as well as economically beneficial. With overall increasing healthy-life expectancy, many Americans will be able to work longer than they do now. Working longer will be health promoting for many Americans, providing not only additional financial security but continued opportunities for social engagement and participation in society. Leave policies related to employee and family sickness are essential to enable workers to remain in the workforce until retirement and at the same time provide social support for their families.

Work-Related and Engagement-Related Policy Alternatives—Priority Considerations

- Strengthening leave policies related to employee and family sickness.

- Evaluating engagement as a core competence of the care plan for older adults.

- Restoring Medicare as the primary payer for health insurance claims for older workers of all employers, with a major communication effort to bring this to the attention of employers and beneficiaries.

- Incentives to redesign work to increase schedule control and increase opportunities for work-family balance.

- A choice of retirement options so that people who cannot continue to work full time or in their previous jobs because of functional limitations can remain engaged in flexible, part-time, seasonal, or less demanding roles.

- Strengthened on-the-job and community-college training programs to hone skills and assist middle and later-life workers in continuing to work or in transitioning to new types of jobs.

- Business tax credits for reinvestment in skill development.

- Strengthened neighborhoods through transportation and housing policies are needed that aim to keep older men and women engaged in their communities.

- Reengineering federal volunteer programs such as Foster Grandparents, RSVP, and Senior Companions to serve a much larger portion of the potential beneficiaries.

- Broadly disseminating intergenerational volunteer programs, such as Experience Corps, which benefit youth and seniors.

Advanced Illness and End-of-Life Care

At some point, the vast majority of older people will face advanced illness, which occurs when one or more conditions become serious enough that general health and functioning decline, curative treatment begins to lose its effect, and quality of life increasingly becomes the proper focus of care. Many such people receive care that is uncoordinated, fragmented, and unable to meet their values and preferences. That often results in unnecessary hospitalizations, unwanted treatment, adverse drug reactions, conflicting medical advice, and higher cost of care.

In September 2015, the Institute of Medicine (now National Academy of Medicine) released Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. The report indicated that there exists a strong body of evidence that can guide valuable improvements in this area, including not only enhancements in the quality and availability of needed care and supports but also strengthening of our overall health system. The report noted a number of important topics to be addressed, including fragmented care, inadequate information, widespread lack of timely referral to palliative care, inadequate advanced-care planning, and insufficient clinician-patient discourse about values and preferences in the selection of appropriate treatment to ensure that care is aligned with what matters most to patients.

Regarding support for clinicians, Dying in America found that there is insufficient attention to palliative care in medical school and nursing school curricula, that educational silos impede the development of professional teams, and that there are deficits in equipping physicians with communication skills. Since Dying in America was issued, there has been progress in many arenas, including the decision by CMS to pay for advance-planning discussions by clinicians with their patients and continued development of innovative approaches to the delivery of palliative care, such as that adopted by Aspire Health, but critical gaps persist.

Advanced Illness and End-of-Life Care—Policy Alternatives

- Government and private health insurer coverage for the provision of comprehensive care for people who have advanced serious illness as they near the end of life.

- Access to skilled palliative care for all people who have advanced serious illness, including access to an interdisciplinary team, in all settings where they receive care, with an emphasis on programs based in the community.

- Standards for advanced-care planning that are measurable, actionable, and evidence-based, with reimbursement tied to such standards.

- Appropriate training, certification, or licensure requirements for those who provide care for patients for advanced serious illness as they near the end of life.

- Integration of the financing of federal, state, and private medical and social services for people who have advanced serious illness as they near the end of life.

- Public education by public health organizations, the government, faith-based groups, and others about advanced-care planning and informed choice, as well as efforts to engender public support for health system and health policy reform.

- Federally required public reporting on quality measures, outcomes, and costs regarding care near the end of life (for example, in the last year of life) in programs that it funds or administers (such as Medicare, Medicaid, and the Department of Veterans Affairs).

Summary

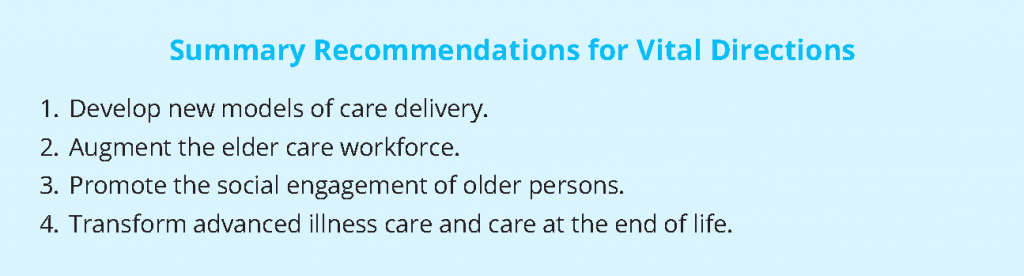

We identify four vital directions for improvement in our capacity to enhance well-being and health care for older Americans:

- Develop new models of care delivery. New models can increase efficiency and value of cost delivery in various care settings and are especially needed for the management of patients who have multiple chronic conditions. Many new evidence-based models are available but have not been widely adopted.

- Augment the eldercare workforce. There are and will be substantial deficiencies not only in the number of physicians, nurses, and direct care workers who have special training and expertise in geriatrics but in the competence of health care workers generally in the recognition and management of common geriatric problems. Addressing these quantitative and qualitative workforce gaps will increase access to high-quality and more efficient care for older persons.

- Promote the social engagement of older persons. Engagement in society, whether through work for pay or through volunteering, is known to have substantial beneficial effects on several aspects of well-being in late life. Evidence suggests that older persons are becoming less engaged, and vigorous efforts to promote engagement can yield important benefits for them and for the productivity of society.

- Transform advanced illness care and care at the end of life. Many people who have advanced illness and especially those nearing the end of life receive care that is uncoordinated, fragmented, and unable to meet their values and preferences. Wider dissemination of available, proven effective strategies can enhance well-being and dignity while avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations, unwanted treatment, adverse drug reactions, conflicting medical advice, and higher cost of care.

The suggestions offered in this paper are within reach, and none is expected to be associated with great cost. In many cases, they call for support of strategies that have been proved to be effective but have not been disseminated widely because of structural or funding limitations in our system. Useful change in all sectors will probably require several years, so urgent action is required now if we are to be prepared when the “age wave” hits. The price of failure would be great, not only with respect to inefficiency but with respect to continued misuse of precious resources, increases in functional incapacity and morbidity, and loss of dignity.

References

- Adler, N. E., D. M. Cutler, J. E. Fielding, S. Galea, M. M. Glymour, H. K. Koh, and D. Satcher. 2016. Addressing Social Determinants of Health and Health Disparities: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201609t

- BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics). No date a. Nursing assistants and orderlies. In Occupational outlook handbook. Available at: www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/ nursing-assistants.htm (accessed March 10, 2016).

- BLS. No date b. Home health aides. In Occupational outlook handbook. Available at: www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/home-health-aides.htm (accessed March 10, 2016).

- BLS. No date c. Personal care aides. In Occupational outlook handbook. Available at: www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes399021.htm (accessed March 10, 2016).

- Eldercare Workforce Alliance. 2014. Advanced direct care worker. Annals of Long-Term Care 22(12):2-5. Available at: https://eldercareworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/EWA_Advanced_DCW_Issue_Brief-pub2014.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

-

Institute of Medicine. 1978. A Manpower Policy for Primary Health Care: Report of a Study. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9932

- Institute of Medicine. 2008. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12089

- Institute of Medicine. 2015. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18748

- MedPAC (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission). 2014. MedPAC data book. Washington, DC: MedPAC. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/publications/jun14databookentirereport.pdf?sfvrsn=1.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2015. The Growing Gap in Life Expectancy by Income: Implications for Federal Programs and Policy Responses. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/19015

- Naylor, M. D., D. A. Brooten, R. L. Campbell, G. Maislin, K. M. Mc¬Cauley, and J. S. Schwartz. 2004.Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52(5):675-684. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x

- Naylor, M. D., K. B. Hirschman, A. L. Hanlon, K. H. Bowles, C. Bradway, K. M. McCauley, and M. V. Pauly. 2014. Comparison of evidence-based interventions on outcomes of hospitalized, cognitively impaired older adults. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research 3(3):245-257. https://doi.org/10.2217/cer.14.14

- National Research Council. 2012. Aging and the Macroeconomy: Long-Term Implications of an Older Population. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13465

- Ouslander, J. G., G. Lamb, R. Tappen, L. Herndon, S. Diaz, B. A. Roos, D. C. Grabowski, and A. Bonner. 2011. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: Evaluation of the INTERACT II Collaborative Quality Improvement Project. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 59:745-753. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03333.x

- Rowe, J. W., R. Grossman, and E. Bond. 1987. Academic geriatrics for the year 2000: An Institute of Medicine report. New England Journal of Medicine 316:1425-1428.

- Schroeder, S. 2016. American health improvement depends upon addressing class disparities. Preventive Medicine 92:6-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.024

- Stone, R. I. 2015. Factors affecting the future of family caregiving in the United States. Pp. 57-77 in Family caregiving in the new normal, edited by J. Gaughler and R. L. Kane. London: Elsevier.