Philanthropy and Beyond: Creating Shared Value to Promote Well-Being for Individuals in Their Communities

This article is a joint publication initiative between The Permanente Journal and the National Academy of Medicine.

Abstract

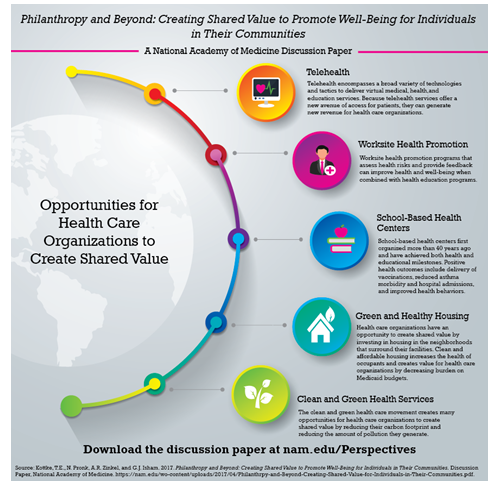

Health care organizations can magnify the impact of their community service and other philanthropic activities by implementing programs that create shared value. By definition, shared value is created when an initiative generates benefit for the sponsoring organization while also generating societal and community benefit. Because the programs generate benefit for the sponsoring organizations, the magnitude of any particular initiative is limited only by the market for the benefit and not the resources that are available for philanthropy. In this article we use three initiatives in sectors other than health care to illustrate the concept of shared value. We also present examples of five types of shared value programs that are sponsored by health care organizations: telehealth, worksite health promotion, school-based health centers, green and healthy housing, and clean and green health services. On the basis of the innovativeness of health care organizations that have already implemented programs that create shared value, we conclude that the opportunities for all health care organizations to create positive impact for individuals and communities through similar programs is large, and the limits have yet to be defined.

Introduction

In 2015, when Tyler Norris was Vice President for Total Health Partnerships at Kaiser Permanente, he collaborated with Ted Howard, President of The Democracy Collaborative in Washington, DC, to challenge hospitals to help heal American communities [1]. They argued that health care organizations should be accountable for all their impacts as they deliver health services and that they should leverage all their assets to create benefit.

One of these assets is philanthropy, characterized by Porter and Kramer [2] as a component of corporate social responsibility. Although it can be used effectively as a tool for benefit, philanthropy is limited by the size of the organization, and it inevitably raises costs and reduces profits. By contrast, initiatives that create shared value are not inherently limited by organizational size because they generate a return on investment for the organization while creating social value and vice versa.

According to Porter and Kramer [2], “The concept of shared value can be defined as policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates.” Their 2011 “big idea” paper offers several examples of initiatives that have created shared value. Among these are:

- Vodafone’s M-Pesa mobile banking service in Kenya [3]. The M-Pesa service creates shared value by decreasing the costs of banking for its customers while generating a profit for Vodafone. In Kenya alone, the service had enrolled 17 million subscribers between March 2007 and December 2011.

- RML (Reuters Market Light) Information Services Pvt Ltd. This service generates income for both Reuters and its customers because, by subscription, it provides weather information, crop-pricing information, and agricultural advice to Indian farmers in their preferred language [4]. RML Information Services Pvt Ltd received a World Business Development Award for this program in 2010 [4].

- General Electric’s Ecomagination. General Electric’s Ecomagination creates shared value by improving economic outcomes for its own operations (revenue of $232 billion generated between 2005 and 2015) and its customers while simultaneously reducing emissions and mitigating other negative environmental impacts associated with commerce [5]. Specific shared-value initiatives include increasing energy efficiency, increasing water reuse, and producing energy-neutral wastewater.

Opportunities for Health Care Organizations to Create Shared Value

The number of opportunities for US health care organizations to implement programs that create shared value is limited only by imagination. In this section, we present examples of five types of products, each of which shows how health care organizations can reach beyond philanthropy and simultaneously create value for themselves while improving the well-being of the individuals, organizations, and communities they serve.

Telehealth

Telehealth encompasses a broad variety of technologies and tactics to deliver virtual medical, health, and education services. Examples of telehealth services are direct clinical services, home health and chronic disease monitoring and management, disaster management, and consumer and professional education [6]. Telehealth services provide consultation through a range of media that include the telephone and Internet so that two or more individuals can consult without travel. The benefits of properly organized and supervised telehealth programs for medical care include lower-cost care; uniform, evidence-based care; care that is more convenient and, in many cases, quicker; travel is eliminated; and the patient neither exposes other individuals nor is exposed by others to infectious conditions. Because overhead is lower and telehealth services offer a new avenue of access for patients, they can generate new revenue for health care organizations.

HealthPartners’ virtuwell is one example of a telehealth service that addresses all 3 components of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim: health, cost, and experience [7,8]. Starting in Minnesota and now licensed in 12 states, virtuwell offers treatment of more than 50 common conditions, including sinus infections, bladder infections, conjunctivitis, and acne. On the basis of an online questionnaire and an interview, a certified nurse practitioner makes a diagnosis, creates a personalized treatment plan, and sends a prescription directly to a pharmacy, if needed. The patient is charged $45, and follow-up care is free. There is no charge if the patient’s condition is not suitable for treatment through virtuwell. HealthPartners estimates that, on average, the services offered by virtuwell would cost $560 if provided in an Emergency Department (ED), $175 if provided in an urgent care center, $140 if provided in a physician’s office, and $89 if offered in a retail clinic. HealthPartners claims analysis calculated that, by the third quarter of 2016, virtuwell had delivered treatment plans to more than 220,000 patients, with an average savings of $105 per visit or a total of $22 million. Nearly all (97%) of the patients agreed that the experience was worth the cost, and 99% agreed that virtuwell is simple to use, saves time, and is safe. Many insurance plans cover the service after the application of copays and deductibles.

Similar to other telemedicine programs, virtuwell creates social value in several ways. Among these are reducing pathogen transmission by reducing visits to clinics and reducing carbon emissions by reducing the need to travel for care. The service also reduces roadway congestion and increases productivity by reducing time away from work for clinic visits.

Worksite Health Promotion in and by Health Care Organizations

Worksite health promotion programs that assess health risks and provide feedback improve health and well-being when combined with health education programs [9,10]. These programs create social value when they reduce disease burden, increase disposable income by reducing health care costs and increase productivity. Because there are markets for these programs, they also create an opportunity for health care organizations to create shared value. Best practices for worksite health promotion programs have been identified [11-13], and a 2013 publication discusses the benefits and opportunities that emerge when health systems integrate lifestyle behavior interventions into their products and services. Case studies also illustrate the substantial improvement in health-related behaviors and reduction in health risk associated with worksite health promotion programs [13, 15].

One example of worksite health promotion is the one implemented, in 1979, by Johnson & Johnson. Associated with the program, average annual growth in total medical spending was 3.7 percentage points lower than for similar large companies between 2002 and 2008 [16]. Company employees benefited from meaningful reductions in rates of obesity, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, tobacco use, physical inactivity, and poor nutrition. Average annual savings per employee were $565 (2009 dollars), producing a return on investment equal to $1.88 to $3.92 saved for every $1 spent on the program [16]. We have calculated that the impact of risk factor changes of this magnitude far outweigh the potential impact that might be achieved by improving access or quality of medical care for acute events caused by heart disease [17]. The benefits of improvements in employee health and productivity can accrue not only to customers of the health care organization but also to the health care organization itself if its own employees can access the program. Worksite health promotion programs have also been associated with improved company financial performance, creating yet another value for the employer [12, 18].

School-Based Health Centers

School-based health centers (SBHCs), first organized more than 40 years ago and now numbering more than 2300, strive to keep students healthy and ready to learn. They have achieved both health and educational milestones [19]. The Community Preventive Services Task Force recommends the implementation and maintenance of SBHCs in low-income communities to improve educational and health outcomes [20]. The positive educational impact includes school performance, grade promotion, and high school completion. Positive health outcomes include delivery of vaccinations and other recommended preventive services, reduced asthma morbidity and ED and hospital admissions, increased contraceptive use among sexually active females, better pre-natal care and birth weight, and improved health risk behaviors. Because SBHCs aim to meet the needs of disadvantaged populations, address the health-related obstacles to educational achievement, and address the cultural, financial, and privacy and transportation-related barriers to clinical, preventive, and health care services, they have the potential to promote social mobility and improve health equity.

A recent analysis reported the economic impact of SBHCs from several perspectives [21]. From society’s perspective, the annual benefit per SBHC ranged from $15,028 to $912,878. From a health care payer’s perspective, especially that of Medicaid, SBHCs resulted in net savings of $30 to $969 per visit. Two cost-benefit studies [21] showed that the societal benefit of an SBHC exceeded the intervention cost, with the benefit-cost ratio ranging from 1.38:1 to 3.05:1, and from the patients’ perspective, savings were also positive because of decreased losses in school attendance, decreased travel time, and improved health.

SBHCs offer two business opportunities to health care organizations. They offer the opportunity to capture new revenue from a new care delivery site with the potential to provide services to school employees, too. Because they are associated with a lower rate of ED visits and hospitalizations, SBHCs reduce the use of expensive care and reduce the risk of needing to provide uncompensated care in the ED and hospital.

Green and Healthy Housing

Health care organizations have an opportunity to create shared value by investing in housing in the neighborhoods that surround their facilities. Clean and affordable housing increases the health of the occupants, particularly by reducing the burden of asthma, and it creates value for health care organizations by decreasing burden on Medicaid budgets. As an example, the Green & Healthy Homes Initiative in Baltimore, MD, describes the case of a woman in Baltimore whose son’s intractable asthma disappeared and her energy bills declined by 30% when the Green & Healthy Homes Initiative corrected the health hazards in her home [22]. She had been about to lose her job because of the time she needed to spend with her son in the ED. After the Initiative’s intervention she received a job promotion and her son joined the honor roll with perfect school attendance. She is now contributing to a 401K and a 529 college savings account. The savings to Medicaid are estimated to be $48,000.

Another example of healthy housing is the collaboration between HealthPartners and St Paul Ramsey County Health Department in Minnesota to reduce the incidence of lead poisoning in the county. When the county Health Department identifies a building where children are being exposed to lead, it works with the landlord to replace the windows, the main source of lead-containing dust [23]. To increase the impact of the program, HealthPartners notifies the county Health Department of the address of residence when its staff members identify a child with high lead levels. Identification can result from screening or because of manifest illness. Because the costs of the windows are partially subsidized by the program and the alternative for the landlord is to bear the full cost if they do not participate in the program, they usually participate.

Because many hospital workers live close to their place of work, clean and affordable housing also benefits the sponsoring health care organization when the health and productivity of hospital employees improve. Because young employees today want to live closer to work and are becoming increasingly concerned with a hospital’s approach to the community and the environment, anchoring neighborhoods can also improve employee retention and improve organizational image in the eyes of its neighbors, a need faced by many health care organizations.

In 2013, David Zuckerman [24] and his colleagues at The Democracy Collaborative published an extensive analysis of the opportunities that hospitals are taking to anchor neighborhoods while satisfying some of their own needs. For example, Bon Secours Baltimore Health System in Baltimore, MD, and St Mary’s Health System in Lewiston, ME, implemented neighborhood revitalization strategies partially because the physical condition of the surrounding community was negatively affecting employee recruitment efforts. Likewise, Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, created a permanent stock of affordable housing in the 1990s because an affordable housing crisis was driving away new employees. Henry Ford Health System and Detroit Medical Center in Detroit, MI, provide financial assistance for potential homeowners and renters seeking to live in Midtown Detroit. Finally, St Joseph’s Health System in Syracuse, NY, and Cleveland Clinic and Cleveland University Hospitals in Cleveland, OH, all offer guaranteed mortgage programs to help reduce the costs of home ownership [24].

Clean and Green Health Services

The clean and green health care movement creates many opportunities for health care organizations to create shared value by reducing their carbon footprint and reducing the amount of pollution they generate [25, 26]. All costs, including those generated by energy-inefficient buildings and the byproducts of care, are borne by patients, and health suffers when community members are exposed to the emissions of coal-fired power plants [25].

Although not the only health care organization committed to creating shared value by reducing its environmental impact, Gundersen Lutheran (now Gundersen Health System) in La Crosse, WI, is an outstanding example

of leadership in clean and green health services. Gundersen is an organization with 41 clinic facilities and a 325-bed tertiary care hospital; a physician-led integrated delivery system with approximately 700 physicians and 6500 employees; residency and medical education programs; a health plan; and a variety of affiliates, including an ambulance service, rural hospitals, nursing homes, and a hospice service. Not only has Gundersen made a commitment to the health and well-being of its patients and communities through its sustainability program, it has spun off a successful consulting business, GL Envision (now Gundersen Envision) [27, 28]. The Envision Web site lists five reasons why Gundersen developed a sustainability program and why other health care organizations would benefit:

- Funds once budgeted for energy expenses can be used to improve margins

- Sustainability programs help to reduce costs associated with disposal

- Sustainable practices are becoming more important to customers and potential employees as they make their choices about where to spend their dollars and where to work

- Emissions from fossil fuels and other hazardous waste have a harmful health impact

- Sustainability is better for the environment.

The Envision program contains 4 components: energy management, waste management, recycling, and sustainable design. Because of these programs, Gundersen Health System generated 72 days of energy independence in 2015, experienced an 81- day stretch of cumulative energy independence (September 11, 2015, to November 30, 2015), and reduced preconsumer food waste by 88% from a 2010 baseline. In 2014, they saved nearly $500,000 by recycling waste.

HealthPartners, in the Twin Cities metropolitan area of Minnesota, has also had considerable success in reducing landfill waste and its carbon footprint through a multifaceted sustainability program [29, 30]. For example, in 2015, it diverted nearly 100 tons (90 metric tons) of operating room waste from landfills, and it decreased paper use by 7.1 million sheets through the implementation of electronic communications. Solar gardens at 2 locations generate enough energy to power nearly 7 houses.

Taking Action and Setting Priorities to Create Shared Value

Unfortunately, the opportunities to create shared value outstrip the available resources; prioritization is required. The organizational resources that are required to develop and to maintain a shared value program, and organizational expertise and naiveté in the area, must be considered when prioritizing initiatives. Although an analytic framework might be seen as easing the prioritization process, we are cautious about adopting one that is more stringent than the criteria defined by Porter and Kramer (and thus constrains thinking): “policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates.” However, we have identified a few issues that must be considered.

The prioritization process is ideally transparent, with the resulting programs addressing community concerns and priorities. Using the local community health needs assessment can help achieve this goal. Both burden and disparity must be considered [31]. For example, even though employed individuals tend to be healthier than the average population [32], worksite health promotion programs can have a major impact because they can reach most American families. On the other hand, although homelessness does not affect nearly as many people, programs that reduce homelessness have a very large impact on each recipient and on the costs borne by health care organizations because the homeless tend to have high needs for health care.

There are additional barriers to the implementation of shared value programs in the health care sector [33]. For example, organizational leaders may need assistance to make the connection between the health of the community and their organization’s business interests. They might not immediately grasp how housing or other community interventions promote their organizational mission. Even if convinced of the value of program development, they may not know what to do.

Case studies of successful shared value programs might increase executive confidence and organizational capability [1, 24]. Participating in a collaborative effort can provide additional guidance and experience. In the field of telehealth, the Center for Connected Health Policy is an organizational resource. For organizations that are interested in building their worksite health promotion capabilities, Health Enhancement Research Organization is an excellent resource [18, 34]. Organizations that wish to improve student outcomes by sponsoring SBHCs might turn to the School Based Health Alliance [35]. Multiple organizations can help health care organizations understand how to create shared value by improving housing stock and access to affordable homes; such organizations include LISC (Local Initiatives Support Corporation) and its partners who are advancing the Healthy Futures Fund, the Corporation for Supportive Housing, and the Build Healthy Places Network [36-39]. Stakeholder Health, an organization of health care organizations that are investing in community development through local purchasing and similar initiatives, can provide insight through shared mission and experience [40]. In the area of environmental action, Practice Greenhealth and Health Care Without Harm are examples of resource organizations. A 2016 National Academy of Medicine workshop summary also describes a number of ways by which businesses can improve the health of

communities [25, 26].

Conclusion

In 2011, Porter and Kramer [2] introduced the concept of creating shared value: adopting “policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates.” In this article, rather than presenting a systematic review of the opportunities to create shared value or potential program impact, we have simply provided examples in five areas where health care organizations might simultaneously advance their own mission and the conditions of the communities they serve: telehealth, worksite health promotion, SBHCs, green and healthy housing, and clean and green health services. Although there are obviously opportunities that we have not described and there are shared value products that are yet to be identified, these examples are evidence of the immense opportunities for health care organizations to create shared value for the communities in which they operate.

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- Norris, T. and T. Howard. 2015. Can hospitals heal America’s communities? “All in for mission” is the emerging model for impact. Washington, DC: The Democracy Collaborative. Available at: https://democracycollaborative.org/learn/publication/can-hospitals-heal-americas-communities-0 (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Porter, M. E. and M. R. Kramer. 2011. Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review 2011 Jan-Feb;89(1-2):62-77. Available at: https://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Vodafone. 2015. M-Pesa: The world’s most successful money transfer service. Newbury, Berkshire, UK: Vodafone Group Plc. Available at: www.vodafone.com/content/index/what/m-pesa.html (accessed February 20, 2017).

- United Nations Development Programme. 2010. World business and development award winners: Fighting poverty can benefit business. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme. Available at: www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2010/09/21/world-business-anddevelopment-award-fighting-poverty-can-benefitbusiness.html (accessed October 6, 2017).

- Frodl, D. 2015. Ecomagination progress. Fairfield, CT: GE Sustainability. Available at: www.gesustainability.com/ performance-data/ecomagination/ (accessed October 6, 2017).

- Center for Connected Health Policy: The national telehealth policy resource center. 2020. Home. Available at: https://www.cchpca.org/ (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Virtuwell. 2020. Home. Available at: www.virtuwell.com/ (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Courneya, P. T., K. J. Palattao and J. M. Gallagher. 2013. HealthPartners’ online clinic for simple conditions delivers savings of $88 per episode and high patient approval. Health Affairs (Millwood) 32(2): 385-92. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1157

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services. 2010. Recommendations for worksite-based interventions to improve workers’ health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 38(2 Suppl):S232-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.033

- Soler, R. E., K. D. Leeks, S. Razi, et al; Task Force on Community Preventive Services. 2010. A systematic review of selected interventions for worksite health promotion. The assessment of health risks with feedback. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 38(2 Suppl): S237-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre. 2009.10.030

- Pronk, N. P. 2014. Best practice design principles of worksite health and wellness programs. ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal 18(1):42-6. https://doi.org/10.1249/FIT.0000000000000012

- Pronk, N. P., and T. E. Kottke. 2009. Physical activity promotion as a strategic corporate priority to improve worker health and business performance. Preventive Medicine 49(4):316-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.025

- Pronk, N. P., D. Lagerstrom, and J. Haws. 2015. LifeWorks@ TURCK. A best practice case study on workplace well-being program design. ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal 19(3):43-8. Available at: https://www.healthpartners.com/knowledgeexchange/display/document-rn945 (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Pronk, N. P., and T. E. Kottke. Health promotion in health systems. Lifestyle Medicine. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Thygeson, N. M., J. M. Gallagher, K. K. Cross, and N. P. Pronk. 2009. Employee health at BAE Systems: An employer health plan partnership approach. In: ACSM’s worksite health handbook. A guide to building healthy and productive companies. 2nd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Henke, R. M., R. Z. Goetzel, J. McHugh, and F. Isaac. 2011. Recent experience in health promotion at Johnson & Johnson: Lower health spending, strong return on investment. Health Affairs (Millwood) 30(3):490-9. https://doi.org/177/ hlthaff.2010.0806

- Kottke, T. E., D. A. Faith, C. O. Jordan, N. P. Pronk, R. J. Thomas, and S. Capewell. 2009. The comparative effectiveness of heart disease prevention and treatment strategies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36(1):82-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.amepre.2008.09.010

- Grossmeier, J., R. Fabius, J. P. Flynn, S. P. Noeldner, D. Fabius, R. Z. Goetzel, and D. R. Anderson. 2016. Linking workplace health promotion best practices and organizational financial performance: Tracking market performance of companies with highest scores on the HERO scorecard. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 58(1):16-23. https://doi.org/10.1097/jom.0000000000000631

- Brindis, C. D. 2016. The “state of the state” of school-based health centers: Achieving health and educational outcomes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 51(1):139-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.03.004

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. 2016. School-based health centers to promote health equity: Recommendation of the Community Preventive Services Task Force. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 51(1):127-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.01.008

- Ran, T., S. K. Chattopadhyay, and R. A. Hahn. 2016. Community Preventive Services Task Force. Economic evaluation of school-based health centers: A community guide systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 51(1):129-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.03.326.

- Green & Healthy Homes Initiative. 2017. Our history. Available at: www.greenandhealthyhomes.org/about-us/history-and-mission (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Ramsey County Public Health. 2016. Lead Window Replacement. Available at: www.ramseycounty.us/sites/default/files/Health%20and%20Medical/Healthy%20Homes/lead_window_replacement_program_brochure.pdf (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Zuckerman, D., H. J. Sparks, S. Dubb, and T. Howard. 2017. Hospitals building healthier communities: Embracing the anchor mission. The Democracy Collaborative at the University of Maryland. Available at: http://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/Zuckerman-HBHC-2013.pdf (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Practice GreenHealth. 2020. Sustainability Solutions for Health Care. Available at: https://practicegreenhealth.org/ (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Health Care Without Harm. 2020. Leading the global movement for environmentally responsible health care. Available at: https://noharm.org (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Envision Gundersen Health System. 2020. Home. Available at: www.gundersenenvision.org (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Baier, E. 2015. Wisconsin hospital’s renewable energy push brings the green. Available at: https://www.mprnews.org/story/2015/06/01/gundersen-renewable-energy-hospital (accessed August 24, 2020).

- HealthPartners. 2016. A snapshot of HealthPartners’ sustainability efforts and initiatives. Available at: https://www.healthpartners.com/hp/about/about-blog/healthpartners-sustainability-efforts-and-nitiatives.html (accessed August 24, 2020).

- HealthPartners. 2018. Make good happen: 2018 annual report. Available at: https://www.healthpartners.com/ucm/groups/public/@hp/@public/documents/documents/entry_184676.pdf (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Kindig, D. 2017. Population health equity: Rate and burden, race and class. JAMA 317(5):467-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19435

- Li, C. Y. and F. C. Sung. 1999. A review of the healthy worker effect in occupational epidemiology. Occupational Medicine 49(4):225-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/49.4.225

- Pronk, N. P., C. Baase, J. Noyce, and D. E. Stevens. 2015. Corporate America and community health: Exploring the business case for investment. Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine 57(5):493-500. https://doi. org/10.1097/jom.0000000000000431

- HERO. 2020. Home. Available at: http://hero-health.org (accessed August 24, 2020).

- School-Based Health Alliance. 2020. Home. Available at: www.sbh4all.org (accessed August 24, 2020).

- LISC. 2020. Home. Available at: www.lisc.org (accessed August 24, 2020).

- LISC. 2020. Healthy Futures Fund. Available at: http://healthyfuturesfund.org (accessed August 24, 2020).

- CSH. 2020. Home. Available at: www.csh.org (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Build Healthy Places Network. 2020. Home. Available at: http:// buildhealthyplaces.org (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Stakeholder Health. 2020. Home. Available at: https://stakeholderhealth.org (accessed August 24, 2020).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Applying a Health Lens to Business Practices, Policies, and Investments: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21842