Using Data to Address Health Disparities and Drive Investment in Healthy Neighborhoods

In struggling high-poverty neighborhoods across the country, community development and medical professionals, who often serve the same population but who have historically operated in silos, are beginning to work together in new and exciting ways. One of the most promising opportunities for advancement in this area is through the use of shared data and metrics to target interventions and measure impact. Community development projects that improve housing conditions, public safety, employment, transportation, walkability, and access to green space and healthy food can have a profound impact on health outcomes. In most cases, however, practitioners of community development and medicine do not have the ability to measure the impact of these projects over time. As a result, the health benefits and related cost savings of these interventions remain essentially invisible.

Several core challenges make it difficult to measure the impact of community development projects on population health. The first challenge is the scale and geography of health data. In most regions across the United States, place-based measures of health are gathered at the county level. This masks important differences among neighborhoods, making it difficult to identify health disparities, target interventions, and measure progress. The second challenge is the sheer number and complexity of factors that influence the neighborhood environment, from very small scale (e.g., the presence of graffiti and litter) to very large scale (e.g., access to regional transit and jobs). The third challenge is population mobility. That is, even when data on health outcomes and neighborhood conditions are available, it is difficult to determine whether improvements in population health are the result of individual people getting healthier or healthier people moving into the neighborhood. Finally, when we can demonstrate that people are getting healthier, the mechanisms or pathways that link environment to changes in behavior and health outcomes are not always clear.

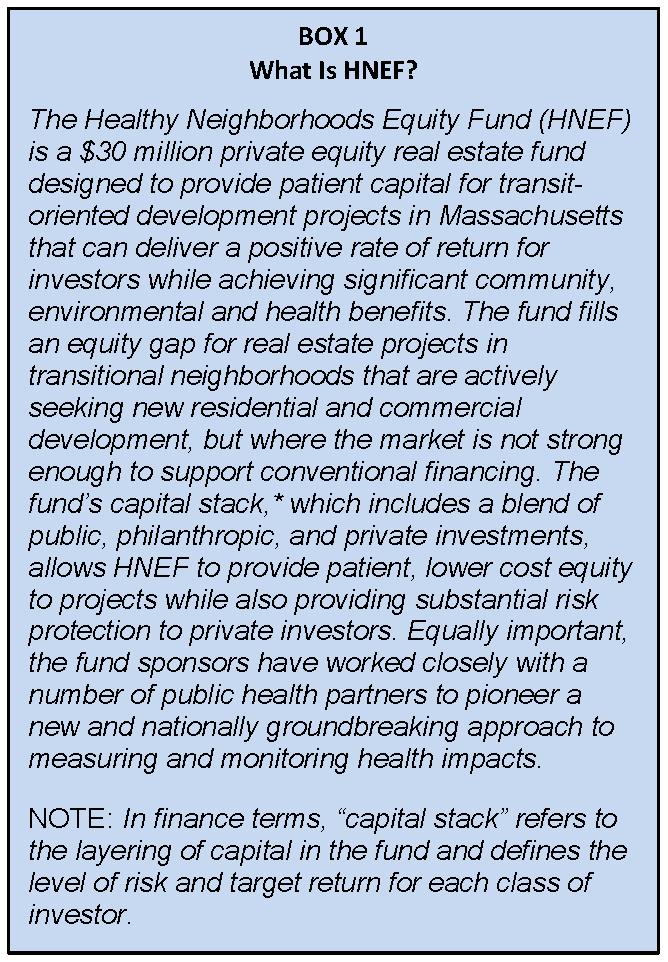

In 2012, I set out on a journey with colleagues from the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) and the Massachusetts Housing Investment Corporation (MHIC) to better understand and tackle these challenges. Our interest in health data and metrics grew out of a collaborative effort to build a new real estate investment fund for transit-oriented development (TOD) (TOD is a type of development that includes a mixture of housing, office, retail, and other amenities integrated into a walkable neighborhood and located within a half-mile of quality public transportation (Reconnecting America, 2013)) called the Healthy Neighborhoods Equity Fund (HNEF, see Box 1). Initially, the fund was conceived as a traditional “triple bottom line” private equity fund aimed at delivering financial returns alongside social and environmental benefits, such as local job creation and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. As we began to investigate the benefits of TOD more closely, however, we realized that this type of development is uniquely positioned to have a measurable impact on community and population health. At the same time, neither CLF nor MHIC had the internal expertise to research and document the links between TOD and health outcomes. Fortunately, the Massachusetts Public Health Association connected us with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) Division of Prevention and Wellness. The timing was perfect, as MDPH was in the process of selecting a new project for a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The HIA process offered a perfect opportunity to look more closely at the evidence, metrics, and data sources linking TOD and health. Over the course of 9 months beginning in January 2013, MDPH and the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC), our regional planning agency, conducted the HIA using three proposed TOD projects in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood as illustrative examples.

The findings and recommendations of the HIA (which are available at http://www.mapc.org/hnef) formed the basis of an investment scorecard that we are now using to evaluate projects for the fund. The scorecard measures the need and opportunity for healthy development in a specific neighborhood, and how well the proposed project meets the need and captures the opportunity. The scorecard is based on a weighted index of more than 50 quantitative and qualitative measures, including secondary data on health outcomes and neighborhood conditions as well as primary data from the project sponsor and a street-level audit of neighborhood conditions. (For the street-level audit, we are using a diagnostic tool called State of Place™ which generates a neighborhood “place rating” based on a block-by-block assessment of more than 160 environmental conditions empirically linked to walking behavior. State of Place is a proprietary analytical tool developed by Urban Imprint. http://www.urbanimprint.com/state-of-place-index/ (accessed November 16, 2015).)

The data we are using for HNEF scorecard (see Table 1) resolves the first two measurement challenges described above. To help assess the overall health of residents in the neighborhood, the MPDH is providing us with Small Area Estimates (SAEs) from the statewide Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Study (BRFSS). The BRFSS SAEs provide Zip code-level data on health conditions and behaviors, including obesity, chronic disease, physical activity, consumption of fruits and vegetables, and mental health, all of which are linked to neighborhood environmental conditions. For scoring purposes, we compare neighborhood-level BRFSS data with statewide data to understand the extent of health disparities in a given neighborhood. While the BRFSS data present some challenges due to sample size, particularly in smaller communities outside of Boston, the tool is important for measuring health outcomes at the neighborhood level. Similarly, MAPC is providing us with an extensive neighborhood dataset on demographics, transit, employment, crime, housing and transportation costs, traffic injuries and fatalities, and access to green space and healthy food. Finally, the State of Place™ rating (which we commission for each neighborhood where an investment is being considered) provides block-by-block data on all the factors that influence walking behavior, including building density and conditions, street connectivity, mix of uses, and pedestrian amenities. Together with the BRFSS and MAPC data, this information creates a comprehensive and detailed picture of community conditions that enables us to more accurately assess the potential impact of a proposed development project.

Finally, building on the partnership and collaboration that has formed around the fund, CLF is also leading a parallel research project aimed at deepening our understanding of the relationship between the built environment and health. Funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, this study will attempt to address the last two challenges described above: namely, the extent to which changes in population health measured at the neighborhood level are attributable to individual health improvement and the mechanisms that link environmental changes to behavioral changes and health outcomes. To help unpack these issues, we will be analyzing individual health records through insurance claims data and other sources (potentially including electronic medical records), combined with surveys and interviews, to track changes in attitudes, behaviors, and outcomes among neighborhood residents over a 10-year period. The research team includes our partners from MDPH, MAPC, and Urban Imprint, as well as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Urban Studies and the Harvard School of Public Health. The research study will also engage local partners through a community-based participatory research process. We hope this study will help to empower local residents and organizations through access to high-quality data as well as by strengthening the effectiveness of community development and public health practice.

The partnerships among CLF, MHIC, MDPH, MAPC, Urban Imprint, and university researchers are fundamental to the success of HNEF (see Figure 1). Without this kind of collaboration, we would be unable to access the data sources we need to effectively target investments and measure the impact of our investments over time. Equally as important, our approach to data and metrics has attracted the interest of public and philanthropic funders and helped to secure commitments to a combined $3.8 million guaranty from The Kresge Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.3 These guaranties, which will absorb some of the risk if projects in the fund do not meet financial return expectations, will make it easier to attract additional private capital and support a larger pool of projects. We hope that HNEF and the associated research study will demonstrate both the value and impact of evidence-based investments in healthy neighborhoods and serve as a model that can be replicated locally and nationally.

References

- Reconnecting America. 2013. What Is TOD? Available at: http://www.reconnectingamerica.org/what-wedo/what-is-tod/ (accessed by November 13, 2015).