Second Annual DC Public Health Case Challenge: Supporting Adult Involvement in Adolescent Health and Education

In 2014, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (On July 1, 2015, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) joined the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Engineering as the third academy overseeing the program units of the newly formed National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (“the Academies”). The NAM has assumed the membership and honorific functions previously held by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), as well as the administration of fellowships, Perspectives, the Rosenthal Symposium, and other activities and initiatives. The IOM has been incorporated as a program unit of the Academies, in which form it continues its traditional consensus study and convening activities. Beginning in 2015, the DC Public Health Case Challenge will be a joint NAM/IOM initiative.) held the second annual District of Columbia (DC) Public Health Case Challenge. (http://nam.edu/initiatives/dc-public-health-case-challenge/ (accessed September 14, 2015)) The IOM collaborated with faculty and students from Georgetown University to develop this competition, which had its inaugural year in 2013 and was both inspired by and modeled on the Emory University Global Health Case Competition. (See http://globalhealth.emory.edu/what/student_programs/case_competitions/index.html for more information.)

The DC Case Challenge aims to promote interdisciplinary, problem-based learning in public health and to foster engagement with local universities and the local community. The Case Challenge engages graduate and undergraduate students from multiple schools, disciplines, and universities to come together to promote awareness of and develop innovative solutions for 21st-century public health issues, grounded in a challenge faced by the local DC community.

Each year the organizers and a student case-writing team develop a case based on a topic that is not only relevant in the DC area, but also has broader domestic and global resonance. Content experts are then recruited as volunteer reviewers to assist the student case-writing team. Universities located in the Washington, DC, area are invited to form teams of three to six students enrolled in undergraduate or graduate degree programs. In an effort to promote public health dialogue among a variety of disciplines, each team is required to include representation from at least three different schools, programs, or majors of study.

Two weeks before the Case Challenge event, the teams are charged to employ critical analysis, thoughtful action, and interdisciplinary collaboration to develop a solution to the problem presented in the case. On the day of the Case Challenge, teams present their proposed solution to a panel of judges composed of representatives from local DC organizations as well as other subject matter experts from disciplines relevant to the case.

2014 Case: Supporting Adult Involvement in Adolescent Health and Education

The 2014 case focused on how to support the adults in the lives of adolescents in Washington, DC, to improve health and education outcomes. The case asked the student groups to develop a program for less than $1 million over 4 years that would fill a void in interventions intended to change adult behavior by increasing the time, quality, and effectiveness of adult involvement in early adolescent education for children 10 to 14 years of age. Each proposed solution was expected to offer a rationale, a proposed intervention, an implementation plan, a budget, and an evaluation plan.

The case framed the issue through five scenarios on a range of issues faced by adults who directly or indirectly interact with adolescents in the defined age group. Though the five scenarios were fictional, they were based on real circumstances involving adolescents in DC. In the first scenario, a high-level official in the DC Public Schools (DCPS) was concerned with rising obesity levels among DCPS students, but had limited support to implement needed changes such as addressing nutrition science in the middle school curriculum and establishing a school garden program. The second scenario looked at the efforts of a DCPS teacher with students who have undiagnosed physical and/or mental health issues that make learning difficult. The third scenario brings to light the struggle of a single parent without financial stability or health insurance coverage who is not able to take an active role in her children’s education. The fourth scenario is of a member of the clergy who lacks training to help adolescents he interacts with relation to matters of health and education. In the final scenario, a nurse practitioner in primary care clinic is caring for a 13-year-old patient who becomes pregnant and has nowhere else to turn.

As background for the case, teams were provided with information that included DC demographics; background on the relationship between health and education; contextual factors linked to health and education, such as social and psychological factors, parental educational attainment, income, environmental factors, and social policies; health risks in early adolescence such as smoking, poor nutrition, inadequate physical activity, and unsafe sexual behavior; information on the DC educational system; clinical care available to DC adolescents; and a sample of available community adolescent programs.

Team Case Solutions

The following student-written, two-page synopses from the six teams that participated in the 2014 Case Challenge describe how teams identified a need, how they formulated a solution to intervene, and how they would implement their solution if they were granted the fictitious $1 million allotted to the winning proposal in the case. (Team summaries are provided in alphabetical order)

American University

Team Members: Gabriel Marcus, Carson Merenbloom, Emily Meyer, Chergai Gao Rittenberg, and Scott Weathers

Summary prepared by Jolynn Gardner, Ph.D., CHES, Team Advisor

Statement of Need

As indicated in the case, adult involvement in a child’s education often results in a wide array of not only improved academic outcomes, but also increased health benefits for the child. The grant opportunity thus sought innovative interdisciplinary strategies to increase adults’ involvement in the education of early adolescents, aged 10-14. Such involvement was hoped to create meaningful, long-term impacts in the lives of DC-area adolescents.

Goal

The American University team created a non-profit organization, Parents & Company, whose mission was “to improve young adolescent academic achievements by supporting parent involvement in the education and wellness of their student.” Parents and Company proposed to achieve this goal through the use of conditional cash transfers.

Intended Outcomes

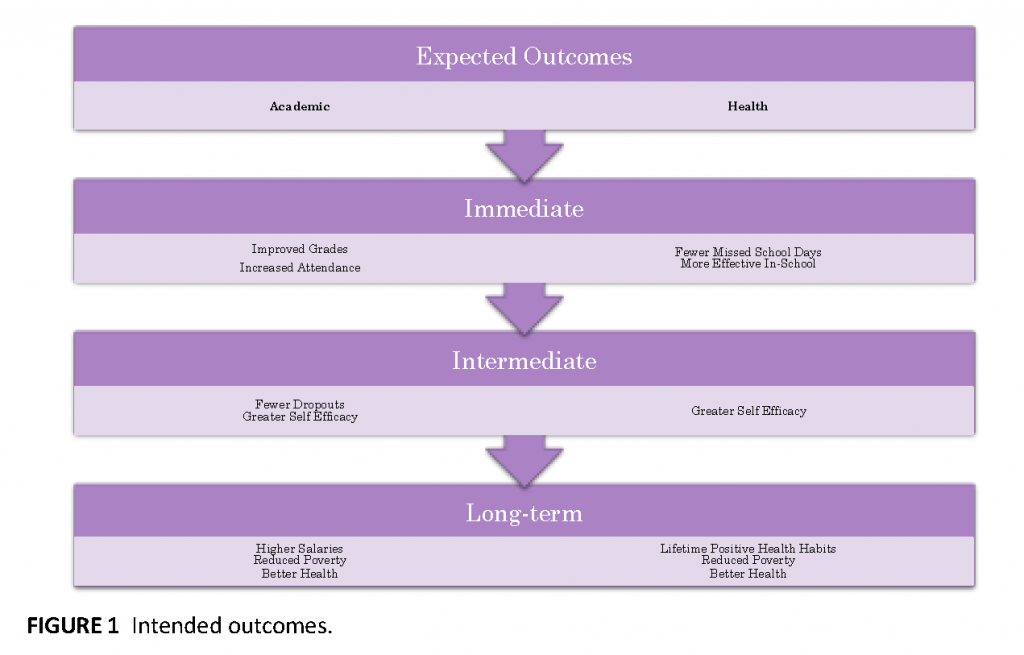

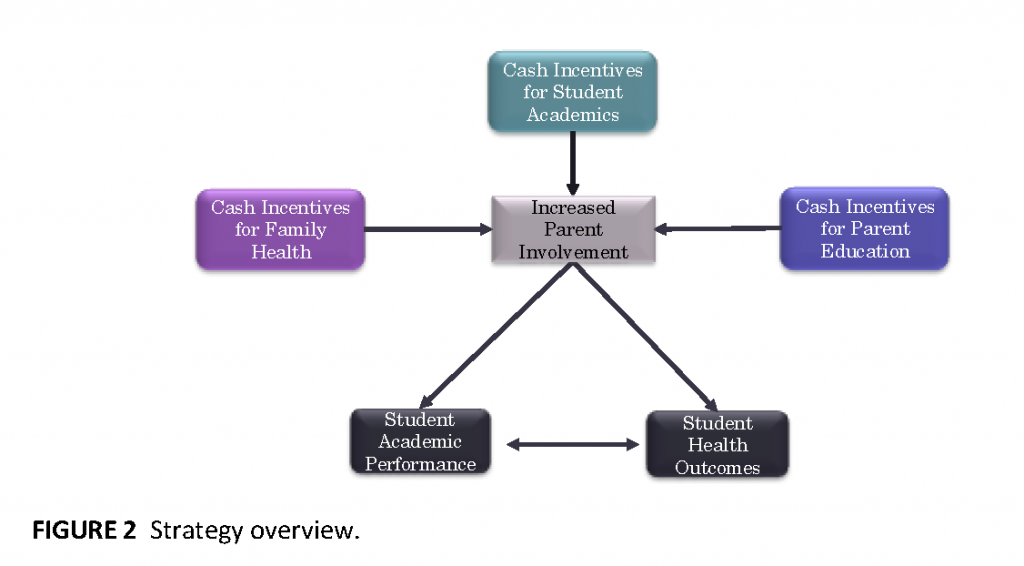

Outcome measures for this strategy focused on the students as well as the parents (see Figure 1). The proposal was that parents would receive conditional cash transfers for helping their students achieve gains in school attendance, improvements in grade point average (GPA), and attainment of higher scores on standardized tests. Cash transfers could also be realized through parent attendance at parent-teacher conferences. Other transfers would be available for parents who signed up for health care coverage and who obtained yearly health and dental check-ups for their family members. The Parents and Company approach sought to help alleviate poverty and improve student wellness by providing financial rewards to children’s families for improved educational and preventive health behaviors. Previous interventions have shown that conditional cash transfers can help alleviate the burden of poverty through cost-effective, short-term interventions that impact long-term measures, such as educational attainment and improved health.

Intervention

The target population for the Parent and Company intervention was Jefferson Middle School in Ward 6 of Washington, DC. The American University team based their strategy on the Health Belief Theory. According to this theory, an individual’s health-related behaviors are influenced not only by their beliefs about health issues, but also by their perceptions of the benefits of and the barriers to engaging in those behaviors. An additional factor influencing behavior is self-efficacy, or the individual’s belief in his or her capability to complete a behavior and attain a given goal. Through the cash transfers, the intervention sought to eliminate barriers to and provide incentives for education-enhancing and health-promoting behaviors. The hope was that as families engaged in these behaviors and experienced positive results, their levels of self-efficacy would improve, leading to further sustained outcomes (see Figure 2).

Strategy Details and Budget

Parents and Company proposed targeting the 100 students in the incoming 6th grade class at Jefferson Middle School. For these students and their families, various financial incentives would be provided for attainment of educational or health-related outcomes or parent attendance at life-skills workshops. The maximum conditional cash transfer amount per student was predicted to be $2,350 per year, and it was anticipated that approximately 80 students and their families would participate. Thus, the conditional cash transfers were projected to account for approximately $188,000 of the yearly $250,000 budget. Other expenses included human resources and administrative expenses.

Potential Barriers and Responses

The American University team recognized that the relatively small cash incentives for each targeted outcome might not be viewed as very enticing by the target population. Thus, a major task for Parents and Company would be to communicate the benefit of fully participating in the program throughout the year, which could yield approximately $2,350 per family. If Parents and Company could then also help the families realize the sustained benefits of their health-enhancing and education-promoting behaviors, then self-efficacy in the target population would potentially improve, leading to continued rewards. Therefore, effective communication and persuasion tactics would need to be hallmark strategies of the organization.

George Mason University

Team Members: Viraj Bhatt, Ayramana Correa, Sara Mullery, Hannah Risheq, and Neil Shelat

Summary prepared by team members

Academic success is well documented as a strong determinant of health—so much so that those who obtain degrees past high school live longer than those who drop out or obtain only a high school degree (Zimmerman and Woolf, 2014; Jemal et al., 2008). Academic success means higher paying jobs in the future, which translate to less stress, better nutrition, and better living conditions. Furthermore, these benefits are passed on to the next generation, because a huge predictor of a child’s health is parental income (Resnick et al., 1997).

DC residents on average are affluent and well educated, yet several wards in DC lag behind the rest of the city. Ward 8 is one of the poorest in DC, with a median family income of $34,700 compared to $88,233 on average. (See http://www.neighborhoodinfodc.org/wards/nbr_prof_wrd8.html (accessed September 10, 2015).) Furthermore, research points to the need for an intervention for middle school-aged children in Ward 8. First, the high school graduation rate in Ward 8 is 79 percent compared to 86 percent city-wide, and daily attendance rates lag behind at 92.9 percent compared to 95 percent citywide (Justice Policy Institute, 2012). Second, participation in risky behaviors is high in Ward 8: Teen pregnancy rates are nearly double the rest of DC, and 37 percent of students are suspended or expelled compared to 13 percent city-wide (Justice Policy Institute, 2012). Finally, only 10 percent of Ward 8 residents graduate from college compared to 47 percent of the entire city (Justice Policy Institute, 2012).

Two primarily interrelated factors limit an adolescent’s academic success: chronic absenteeism and dropping out of school. Multistate analyses found chronic absenteeism to be the strongest predictor of dropping out of high school, stronger even than suspensions, test scores, and being over age for grade (Balfanz and Byrnes, 2012). Furthermore, chronic absentee rates are three times higher among young people from low-income families, as are many youth from Ward 8 (Balfanz and Byrnes, 2012). Additionally, adolescence is a critical time for parents to help prevent absenteeism and dropping out; around the time a student enters middle school, their parents’ involvement decreases (“Problems and promise of the American middle school,” 2004) (See http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB8025.html (accessed September 10, 2015).) and their likelihood of being absent from school increases (Balfanz and Byrnes, 2012).

Lack of family involvement in an adolescent’s life is a key to reducing absenteeism, as unsupervised time not spent in the classroom can mean engagement in risky behaviors on the streets of their neighborhoods. This means they are more likely to partake in risky behaviors like unsafe sex, substance abuse, and violence (“Vulnerable youth and the transition to adulthood,” 2009). To improve lifelong health outcomes, programs must concentrate on interventions early in life that reduce absenteeism, provide education on reducing risky behaviors, and improve an adolescent’s chance of completing high school. Our program, Easy as Pi, does this by engaging caregivers, incentivizing regular school attendance, teaching health education and relationship building, and ultimately reducing absenteeism.

Our program has three components: workshops, a food truck, and scholarships. First, our program offers pie-baking and health education workshops for adolescents and their caregivers/parents. Workshops will operate on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays to allow families flexibility with their schedules. For regular participants whose children attend school every day (tracked via a partnership with DCPS), $40 cash incentives are disbursed to parents upon attending a workshop—and if they attend every week, they can accrue up to $800. Parents and adolescents participate in a healthy piebaking workshop and then take part in health education courses while the pies are baking. Pies may not immediately seem like a healthy choice, but there is a strong push in nutrition programs to meet families “half-way” and encourage incremental changes by using healthier versions of ingredients with which families are familiar. The health education curriculum, based on the highly successful Strengthening Families Program designed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, has been successfully implemented in programs for at-risk youth and concentrates primarily on alcohol and drug abuse prevention.

Second, the program staff will operate a food truck several days a week that sells pies baked by participants. Pies are popular items in the food truck market right now and can be sold at a huge profit of $21 per pie. Third, our program encourages adolescents to stay in school and pursue higher education through scholarships. We recognize the importance of motivating students to pursue higher education, as the large price tag often keeps students from even considering college. Therefore, profits generated by the food truck go into a scholarship fund for participants who go on to graduate high school and pursue secondary education. Due to the high profit margin from selling pies, with sustained attendance both in our program and at school, our program could provide consistent participants with a $2,700 scholarship.

Finally, the most intriguing part of our program is the fact that it is self-sustaining beyond the 4-year funding, allowing our program to exist independently of additional funding, and making it extendable to school districts around the country. Although we will require grant funding through year four, when funding runs out, we are still able to contribute roughly $1,400 per student in annual scholarship funding, in addition to the weekly $40 gift cards. We hope to bridge that drop with corporate contributions and charitable donations.

Georgetown University

Team Members: Chandani Desai, Caitlin Ingraham, Leah Broadhurst, Nathan Praschan, and Samuel McAleese

Summary prepared by team members

Overview

“Better Together” is a mental wellness and resilience-building initiative. Our initiative seeks to promote mental and emotional wellness in adolescents by partnering with their parents and teachers. When discussing mental health and education in Ward 8, we quickly realized how vibrant and strong this community is. Children do not exist in a vacuum. They are surrounded by a greater community of adults who have learned important lessons about self care and resilience. Our main goal is to harness the accumulated experience of the community to empower parents and teachers to model resilience against stress to adolescents.

“Better Together” will create a space for caregivers and teachers to affirm resilience among each other, share stress management skills, and connect with existing resources. In that space, “Better Together” will also empower caregivers and teachers to teach resilience and stress management to adolescents with a resilience-building curriculum. Ultimately, by improving stress management in adolescents, “Better Together” will improve educational outcomes.

“Better Together” will begin its initiative by rooting itself in the richness of the community of Ward 8 in Washington, DC. Ward 8 has a history of strong community engagement and resilience building, caregivers invested in education, supportive small business leaders, and social support. In the first 4 years of the program, the initiative will focus specifically on the community around Kramer Middle School, which has been designated as a Priority School by DC Public Schools and already has a strong history of parent and teacher investment in the success of its students. The theoretical framework of “Better Together” is divided into phases to achieve success: Phase I (Planning and Partnering), Phase II (Action through Teaching), and Evaluation and Adjustment (see Figure 3).

Phase I

In the first year, using the guiding theoretical frameworks of Ground-Based Theory and Participatory Action Research, we will engage the community through an open dialogue that not only identifies the strengths of the community, but also ensures that each community member has a voice in the improvement of their community’s educational outcomes. Identifying community partners (e.g., pastors, DCPS administrators, Principal Kwame Simmons) will allow us to tailor the program to the specific needs of the community. A postdoctoral fellow in education and a team of community health workers (CHWs) will develop a curriculum with input from community focus groups of both students and adults. The resilience-building curriculum will be modeled on preexisting, evidence-based curricula and tailored to promote the specific strengths found within Ward 8. This curriculum will be enacted during parent meetings in Phase II to give parents the opportunity to share with each other the coping skills that they can bring home to their children. Importantly, the CHWs will be from the community, creating a stronger bond between “Better Together” and the community. The focus groups will be facilitated by the postdoctoral fellow and the CHWs. Potential topics will include asking adults what helped them succeed in school and asking adolescents for an initial assessment of their attitudes about mental health and school.

Phase II

After establishing a strong understanding of the community and developing a curriculum, Phase II will move forward with implementation. The aim for this phase is to translate the past successes of the community into improved parent, teacher, and child mental health behaviors. Our postdoctoral fellow will train teachers to be aware of key indicators in mental wellness and resilience, gearing these teachers to look for factors such as:

- How is the student managing work?

- How is he/she interacting with other students?

- Is the student bringing stressors from home to the classroom?

- What is his/her mood? Is he/she tired? Hungry? Interested in the lesson plan or ambivalent?

This training will also equip teachers with skills to pass onto their students, tailoring the teachers to be an effective resource to each child. For example, teachers can introduce skills early on, such as breathing exercises when feeling anxious before a test. As a key role model in students’ lives, teachers can illustrate that dealing with stress is a universal task. The overall goal is for children to develop a more positive outlook on stress and resilience and to encourage children to be open and seek help.

Simultaneously, CHWs will work with caregivers at monthly meetings, bringing together adults who have already dealt with hardships, stress, difficult times, and/or anxiety. CHWs, guided by curricula developed in Phase I, will facilitate conversations about coping strategies by providing community resources for and teaching new skills to parents. This type of peer-to-peer learning takes a standard curriculum and makes it relevant to an individual parent’s struggle. At these meetings, parents will not only learn generic techniques, but also how their neighbors deal with similar struggles, teach discipline, and address issues in mental wellness that are rarely discussed. Most importantly, parents will be encouraged to teach their children about the coping strategies discussed in these monthly meetings. As a result, “Better Together” will bring positive change to both adult health outcomes and student educational outcomes at Kramer Middle School (See Figure 4).

Evaluation

We plan to evaluate our intervention at each phase and make improvements as needed. Initially, we plan to use the data gathered from early focus groups to drive the implementation of Phase II. To do this, we will pretest our questionnaire instruments and pilot test our intervention with a small subset of the community. Once our intervention is underway, we will perform a process evaluation that will look at the number of teachers trained and attendance at our caregivers’ meetings, and track any contact between CHWs and caregivers. Furthermore, we want to examine the impact of our intervention on the population. We will screen caregivers for improved stress management, and screen their children for improved resilience. Finally, we will look at long-term outcomes of the program by tracking and assessing students for improved behavior in school, attendance, and graduation rates.

Budget

The peer teaching of “Better Together” is driven by parents and teachers within the community, which allows for a small administrative staff composed of a postdoctoral fellow and CHWs who will recruit, run the monthly meetings, and follow up with parents regularly between meetings. Salaries comprise 55 percent of the budget. Additional funds are for overhead, incentives, and training opportunities for CHWs.

Conclusion

The greatest foreseeable challenge in implementing “Better Together” is community investment in the program: Why should parents spend time away from their homes to learn how to deal with stress and impart that wisdom to their children? By providing a nurturing space filled with both peer support and peer knowledge, our hope is that parents will want to engage in social learning, rather than simply attending lectures on stress management. By encouraging parents and partners to participate in the planning and execution of “Better Together,” we hope to leverage the enthusiasm and expertise of the community to augment our intervention in innovative ways. This engagement also creates an organic path to discovering the next challenge areas that need to be addressed. Parents and teachers, who will be the driving force behind “Better Together,” know their community and will identify new areas of growth for the program. “Better Together” is not an intervention, but rather a catalyst for change within a community that seeks to acknowledge and build on the existing resilience of the community and its leaders. As a result, the program can be implemented not only in Ward 8 to address mental health and dropout rates among adolescents, but also in any community seeking improvement in adolescent wellbeing.

The George Washington University

DC Public Health Case Challenge 2015 Grand Prize

Team Members: Carrie Gillispie, Sandy Fulkerson Schaeffer, Erin Prendergast, Courtney Middlebrook, and Mamta Chaudhari

Summary prepared by team members

DEAN: District Early Adolescent Navigator

Introduction

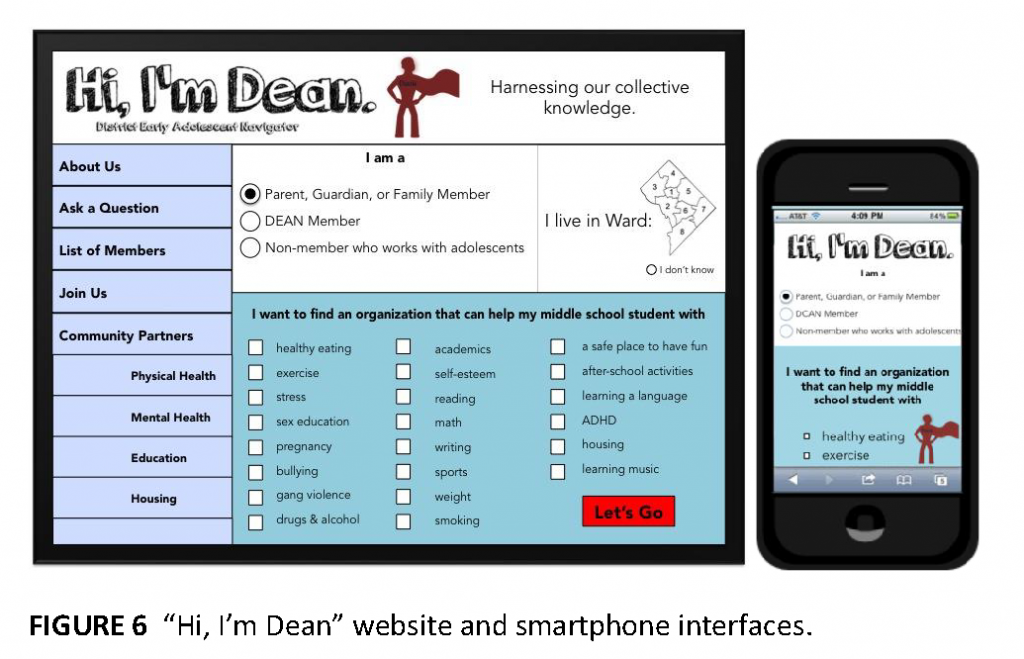

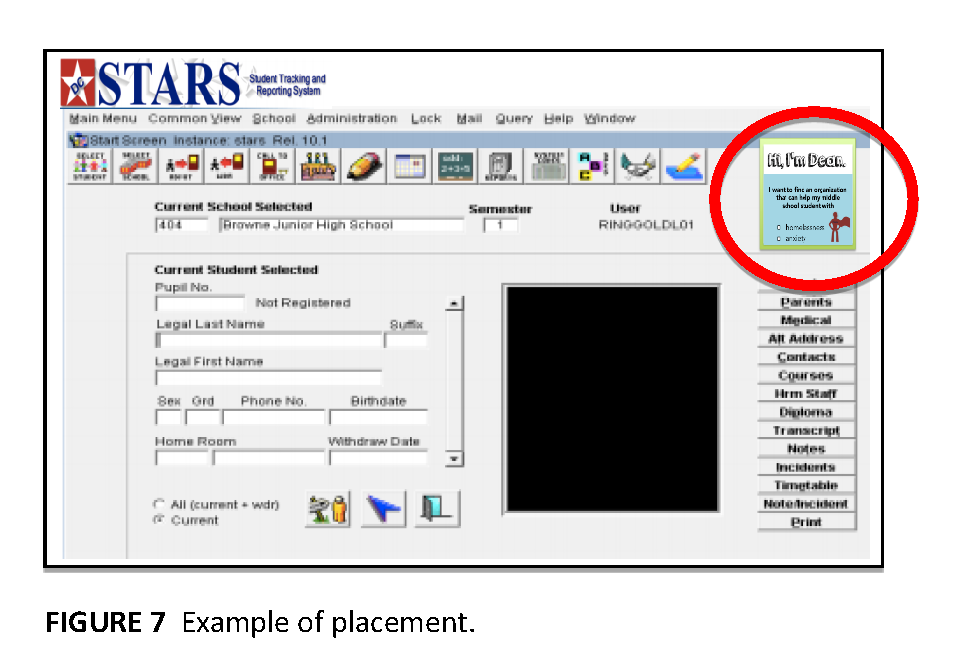

The District Early Adolescent Navigator (DEAN) is a collaborative, interprofessional network of direct service providers that will enable sustainable communication and behavior change among the adults who are important in the lives of early adolescents. DEAN’s mission is to lessen the burden of families and health/education providers who serve early adolescents. To address this mission, the DEAN initiative will involve capitalizing on and promoting existing resources and services to amplify their functionality; identifying similarities among these resources and services in order to mitigate redundant efforts and increase collaboration; identifying differences between these resources and services in order to hone their unique strengths; providing comprehensive supportive services; and ultimately harnessing the collective power of the stakeholders invested in early adolescent health and education. DEAN will be designed to link early adolescents in DC to the organizations and services already operating in the city, and will do so through an online platform featuring these local organizations and services; in-person “Navigators” of that platform; and biannual in-person meetings for Navigators and representatives of the local organizations and services.

Online Platform

The DEAN website will be a searchable database of member organizations that have met and/or exceeded inclusion criteria for high quality and effectiveness. Each organization will list key information and the name of at least one contact person/role. The website will be 508-compliant with text at a sixth grade reading level, and will be available in multiple languages so that nearly any adult with an early adolescent in their life can access the information. The website will also be mobile accessible, enabling anyone with a smartphone or tablet to access DEAN.

In-Person Navigators

For those who prefer and/or need in-person support, DEAN Navigators will operate in DC Public Library (DCPL) branches. Initially, these Navigators will be Library Technicians or Associates, as these specific DCPL staff members already interact with dozens of early adolescents and their families each week. DEAN staff will hold an initial training session for DCPL staff to teach them all user-facing components of the website, including the search and filter functions as well as how to update a service listing. Refresher training sessions will be held annually, and DCPL staff will be encouraged to contact DEAN staff as often as needed to troubleshoot and resolve questions with the site. Once trained as DEAN Navigators, DCPL staff can use their skills to assist primarily adults who interact with early adolescents in finding important social services, after-school activities, summer camps, health care, and more.

Biannual Meetings

In addition to being featured on the DEAN platform, representatives from every DEAN service provider will participate in biannual coalition meetings to cultivate a sense of community and shared vision, to share knowledge, and to collaborate on issues unique to early adolescents in DC. These meetings will include panel discussions, trainings on topics such as cultural competency and best practices, and invitations to outside entities such as the DC Mayor’s Office. The meetings will provide opportunities to exchange solutions and/or find resolutions to problems that participants notice in the community. In the initial year of the coalition meeting, a code of ethics and by-laws will be established among the participating organizations to set a baseline that standard participating organizations must meet. The behavioral norm for early adolescent service providers will be the act of coming together on a regular basis to leverage interprofessional frameworks and practices to collectively solve problems.

Budget

People power will be fundamental to DEAN’s success, so the majority of the budget will be allocated toward DEAN staff salaries: $205,000 per year for the 4-year funding period. Staff responsibilities will include website platform creation and maintenance; biannual meeting program development and implementation; and DEAN network coordination and direction/technical assistance. The heavy staff workload will be supplemented with graduate student interns and volunteers. Of note: DEAN will have a diversified funding plan that incorporates fundraising, grants, and public-private partnerships.

Monitoring and Evaluation

DEAN’s monitoring and evaluation plan consists of a process evaluation conducted during the first 3 years of the project as well as an impact evaluation conducted during the last year of the project. The process evaluation will track project implementation across activities. Data will be collected by DEAN staff from a variety of sources—database reports, surveys, and web analytics—to ascertain successful implementation of the project activities. For example, the number of service providers that opt to be added to the DEAN website will be collected to demonstrate effective marketing to and recruitment of service providers.

The impact evaluation will assess both the expected and unexpected outcomes of each activity. DEAN staff will use collected data and process evaluation results to evaluate the overall impact the project has on the target population. This evaluation will answer the following questions: To what extent are the adults involved with early adolescent health and education services networking with one another and receiving supportive services? To what extent are these services improving early adolescents’ health and education outcomes?

Implications

DEAN will facilitate collaboration and cooperation among libraries, schools, and service providers. Rather than creating another program aimed at early adolescents, DEAN will both 1) improve the capacity of existing services that address the health and well-being of early adolescents, and 2) increase the referral to and/or usage of these services by youth-serving adults, parents, and young people, respectively.

Howard University

Team Members: Cameron Clarke, Atila Libutsi, Demi Lewis, Emilie Biondokin, Sarah Baden, Adria Peterkin

Summary prepared by team members

The following intervention addresses the difficulties and failures of the educational system to serve teenagers and adolescents. Washington, DC, has a population of over 650,000, with more than 25,000 of its residents between the ages of 10 and 14. Wards 7 and 8, in the Anacostia region of Southeast DC, are the two poorest and have the highest concentration of African Americans.

In Ward 8, where the population is 94 percent African American, 19 percent of adults lack a high school diploma, and 22 percent are unemployed. Ward 7 has similar statistics, with 17 percent of adults lacking a high school diploma, and an unemployment rate of 19 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). Academic success and educational achievement are strong predictors of overall health and employment outcomes later in life, and poorer health in adolescence is strongly negatively associated with educational attainment. A study conducted by the Harvard School of Education, and published in the Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness found that “frequent teacher-family communication immediately increased student engagement as measured by homework completion rates, on-task behavior, and class participation. On average, teacher-family communication increased the odds that students completed their homework by 40 percent, decreased instances in which teachers had to redirect students’ attention to the task at hand by 25 percent, and increased class participation rates by 15 percent” (Kraft and Dougherty, 2012, pg. 1). Formalized and effective teacher-family communication improves student outcomes, but in practice, an effective medium has not yet been discovered to achieve this improvement. Much of the difficulty in creating an effective program to address the gap between low-achieving students stems from the fact that African-Americans are less likely to have in-home Internet access than their white peers. However, they are slightly more likely to be mobile phone users. (See http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/01/06/african-americans-and-technology-use/ (accessed September 10, 2015). This research indicates that the ideal platform to foster communication between students, parents, and teachers would be an integrated mobile phone application and website. Our intervention uses this theory and operates off of the assumption that if parents and teachers were better informed about their children’s health, they could more effectively communicate with the student and tailor their expectations to their students’ needs. The intervention, beTWEENS, is an online resource and forum that provides the opportunity for parents and students to interact with health professionals and educators on a consistent basis (see Figure 8 for the beTWEENS logo).

Logging on through the adult portal allows parents to reach out to their child’s health professional or educator. Parents may also communicate with other parents through forums and access even more resources to communicate with their child. When communicating with doctors, beTWEENS would function as a secure online cloud healthcare database, allowing doctors to share patient information with parents and parents to access data, request appointments, and send messages. When communicating with teachers, beTWEENS would function as an interactive online gradebook, allowing parents to communicate with teachers and share grades and assignments, in the vein of Engrade, a system used throughout DCPS. Logging on as a student would allow teens to stay connected with their health professional and teacher, seek professional advice from our “Tween” counselors, play games, post videos, and access third-party health and educational resources. For physicians with MyPatient Portal, patient information updated through the portal would automatically be securely mirrored on beTWEENS, giving them greater ease of access to forward patient information to parents.

Because the beTWEENS program would be available as a website and as a mobile app, it would allow students and parents without in-home Internet access or computers to still be able to keep up with their progress. Finally, all of the information stored through the adult and tween sites and through the mobile app will be completely compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, commonly known as HIPAA. Protected data encryption, intrusion prevention, and password protection would be used throughout to protect patient data.

Over the course of the program, we believe we would be able to improve outcomes in adolescent health and education. We will evaluate the success of our intervention by collecting information related to high school graduation rates, GPAs, and standardized test scores, relative to a control group. We believe long-term benefits would include increased quality of life, decreased mortality, and reduced unemployment rates.

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

Team Members: Kalpana Parvathaneni, Brandon Shumway, William Patrick Luan, Holly Berkley, Morgan Harvey, Kristin Wertin, Asad Moten, Uneeb Qureshi

Summary prepared by team members.

“DC&ME after 3:00”: An After-School Program Database

To address the given challenge of improving the health outcomes for early adolescents by supporting adult involvement, we propose our concept of “DC&ME after 3:00.” Our objective is to increase the interactions between adults and kids by creating a robust, searchable after-school program database. By developing a cohesive network of university students to connect parents and their children with quality programs, we hope to empower youth by engaging them with the community. The key factors in an adolescent’s growth and development include education, health, and social and emotional well-being, which are interrelated. Our challenge is to increasing adult involvement in these areas of the adolescent’s life. In a recent Washington Post article (Balingit, 2014), Dr. Nancy Deutsch from the University of Virginia stated, “The hours between 3 and 6 p.m. are very important as this is the time when most youth are most likely to engage in risky behavior.” First we want to ask, “Where are the sixth to eighth grade students from 3 to 6 p.m. in the DC area?” According to the survey by After School Alliance in 2014 (ASA, 2014), 45 percent attended after-school programs, but 55 percent of DC kids were not enrolled in any after-school program, which implies they were with an untrained adult, in sibling care, or unsupervised. After-school programs keep kids safe, healthy, and on track for success through structured adult interaction. Research (ASA, 2013a, b) shows that attending these programs decreases delinquency or juvenile crime, truancy, drug use, alcohol consumption, smoking, and unprotected sexual activity. Benefits of attending these programs include increases in school attendance, engagement in learning, grades, test scores, and graduation rates, which all contribute to better outcomes for students (Little et al., 2008).

Focus and Outreach

Our proposed plan is to focus on the at-risk populations in Wards 7 and 8 with high rates of negative social indicators related to school drop-out rates, health, housing, and education. Adolescents in these wards should have access to quality programs to help overcome these disparities (Sachdev, 2012). These areas do have programs such as the YMCA, Brainfood, Shakespeare theatre, Smyal, Triple Play, and Urban Ed, to engage students in after-school activities like sports, arts, and education. But because working parents may not be able to access or understand information, these programs are not used to their full potential. The missing link between parents and the program will be filled by our tool, “DC&ME after 3 p.m.”

Implementation

To maximize the after-school program potential, we need the following factors:

- Access to programs and sustained participation;

- Quality programming and staffing; and

- Partnerships with schools, families, and community institutions.

We developed a three-step proposal to quantify the need for an after-school alliance program. To achieve this, we will perform a mixed-method evaluation in Wards 7 and 8 with preliminary qualitative needs assessment and a tablet-based survey. Our next step will be to create a searchable web-based tool to integrate into an existing database, Project My Time, to link parents to appropriate after-school programs. Project My Time was developed in 2008 by the DC Children and Youth Investment trust Corporation to help parents locate after-school programs based on Zip code, ward, and program type. Despite initial success, this database lacks any other information and has not been updated due to lack of continued financial support. Our approach will be to build up the existing database and introduce more searchable parameters such as cost, availability of subsidies, student age ranges, transportation options, special needs, language, ratios of adults to students, ratios of male to female students, program hours, and categories, such as performing arts, fitness, and academic assistance. Our last step will be to empower undergraduate students from local universities to spread the word in the community. These volunteers will conduct surveys, maintain the database, and act as parent–tool liaisons. Faculties will be employed to train and guide the students and provide oversight for the duration of the project. Faculty will also set up local events to link parents with after-school program representatives. Events will be organized with DCPS, houses of worship, and other community events. Parents will be provided with information based on the needs of their children and directed to an after-school representative to obtain further information about specific programs.

Evaluation Strategies

We will evaluate the progress of the project by conducting a survey on Wards 7 and 8 participation in after-school programs. We will also monitor the number of students enrolling in afterschool programs at “DC&ME after 3:00” community events. We will evaluate the success of the project by monitoring the attendance rates at after-school programs.

Potential Barriers and Mitigation Strategies

Potential barriers include a low response rate in parent surveys and/or program director interviews. These can be mitigated by providing incentives for every survey completed. Low attendance at community events can be improved by involving key stakeholders, including religious leaders, schools, and health care providers. Yearly surveys may not accurately reflect the success of the program, which can be averted by increasing sensitivity and availability of the feedback on programs. Lack of existing after-school program capacity can be measured by need-based evaluation surveys, which will likely increase visibility of program needs to funders.

Conclusion

Local university students who serve as liaisons with parents of adolescents to promote a searchable database of after-school programs will reduce barriers to access and promote targeted funding to improve existing after-school programs. Universities, DCPS, and community stakeholders are connected in a common goal to provide and improve the healthy lifestyle of adolescents. Adolescents are engaged with adults during after-school hours that keep them safe from harm’s way and improve their overall well-being as they are connected to programs that meet their particular needs.

Follow-Up Event

To continue engagement of the student participants in the Case Challenge subject matter and in its practical application in the local community, the IOM convened a follow-up event to the competition in February 2015. This event highlighted the work of Washington, DC agencies and organizations working to improve health and education outcomes in the city. The day focused on two themes that emerged from the student solutions to the Case Challenge: connecting service providers for youth wellness and parental involvement in youth health and learning. It brought together panels of DC-based non-profit organizations that work in the area of health or education, DC Public School officials, and parents and students from DC schools.

Three teams from the competition in the two focus areas were invited to present their solutions to these panels. The event served as an opportunity for those who implement and live with these issues to engage with the students in a rich discussion on how to make improvements and inculcate action at the nexus of health and education in Washington, DC. The follow-up event, similar to the follow-up event to the 2013 Case Challenge—which focused on violence against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth—resulted in rich and thought-provoking discussions, introduced new relationships, and spurred additional innovative ideas.

Future Plans

The Case Challenge and follow-up event have served together as a means of bringing the work of the IOM to both university students and to the DC community. The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) and the IOM are therefore committed to continuing this activity with the 2015 annual Case Challenge, which will focus on health and aging in Washington, DC. It will be sponsored and implemented by the IOM Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, (See http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Activities/PublicHealth/PopulationHealthImprovementRT for more information.) with the support of the IOM’s Kellogg Health of the Public Fund and the engagement of related activities of the IOM, including the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education (See http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Activities/Global/InnovationHealthProfEducation.aspx for more information.) and the Forum on Aging, Disability, and Independence. ( See http://iom.nationalacademies.org/activities/aging/agingdisabilityforum.aspx for more information.) NAM and IOM staff continue to look for new ways to further involve and create partnerships with the next generation of leaders in health care and public health and with the local DC community through the Case Challenge.

Acknowledgments

The 2014 Case Challenge was funded by the IOM’s Kellogg Health of the Public Fund and the IOM Roundtable on Population Health Improvement. The Kellogg Fund is “intended to increase the IOM’s impact in its efforts to improve health by better informing the public and local public health decision makers about key health topics, as well as by developing targeted health resources and communication activities that are responsive to the needs of local communities.” The Roundtable brings together individuals and organizations that represent different sectors in a dialogue about what is needed to improve population health. The Case Challenge was carried out with additional support from the IOM Global Forum on Innovation and Health Professional Education.

The 2014 case was written by a student team composed of students from the participating local universities. Sweta Batni (Georgetown University) led the case writing team, and ENS Yaroslav Bodnar (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences), Desirée Bygrave (Howard University), Christine A. Clarke (Howard University), Victoria Larsen (Howard University), Megan Prior (Georgetown University), and Laura-Allison Woods (George Mason University) provided additional research and writing support.

The co-founders and organizers of the Case Challenge were again crucial to the success of the 2014 event and include Anne Rosenwald and Ranit Mishori from Georgetown University, and Leigh Carroll and Bridget Kelly from the IOM. The staff from the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, Alina Baciu, Amy Geller, and Colin Fink, came on as new partners in 2014 and assisted with the development of the topic and implementation of the 2014 Case Challenge.

Finally, input from both local and national experts is vital to the success of the Case Challenge. Thomas A. LaVeist from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Erika Vijh, student in the Master of Health Services Administration program at the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor and former IOM staff, served as external reviewers of the case and offered valuable feedback. Gillian Barclay, vice president of the Aetna Foundation and member of the IOM Roundtable on Population Health, Diane Bruce, director of health and wellness for the District of Columbia Public Schools, Tiesha Butler-Williams, leadership development coordinator at Metro TeenAIDS, Jason S. King, president of Turning the Page, Harrison C. Spencer, president and CEO of the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health and member of the IOM Global Forum on Innovation and Health Professional Education, and Erika Vijh, also a case reviewer as noted above, served as judges at the 2014 event.

References

- ASA (After School Alliance). 2013a. Afterschool programs: Making a difference in America’s communities by improving academic achievement, keeping kids safe and helping working families. Available at: http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/Afterschool_Outcomes_2013.pdf (accessed September 10, 2015).

- ASA. 2013b. The importance of afterschool and summer learning programs in African-American and Latino communities. Issue Brief No. 59. Available at: http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/issue_59_AfricanAmerican_and_Latino_Communities.cfm (accessed September 10, 2015).

- ASA. 2014. District of Columbia after 3 pm. Available at: http://www.afterschoolalliance.org/documents/AA3PM-2014/DCAA3PM-2014-Fact-Sheet.pdf (accessed September 10, 2015).

- Balfanz, R., and V. Byrnes. 2012. The importance of being in school: A report on absenteeism in the nation’s public schools. Available at: https://ct.global.ssl.fastly.net/ (accessed September 10, 2015).

- Balingit, M. 2014. Group calls for increased investment in after-school programming. The Washington Post. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/group-calls-for-increased-investment-in-after-schoolprogramming/2014/10/16/13e1349c-554f-11e4-809b-8cc0a295c773_story.html (accessed September 10, 2015).

- Jemal, A., E. Ward, R. Anderson, T. Murray, and M. Thun. 2008. Widening of socioeconomic inequalities in U.S. death rates, 1993-2001. PLoS ONE 3(5):e2181. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002181

- Justice Policy Institute. 2012. The education of D.C.: How Washington, D.C.’s investments in education can help increase public safety. Available at: http://www.justicepolicy.org/uploads/justicepolicy/documents/education_of_dc_-_final.pdf (accessed September 10, 2015).

- Little, P., C. Weiss, and H. B. Weiss. 2008. After school programs in the 21st century: Their potential and what it takes to achieve it. Harvard Family Research Project, Issue 10. Available at: https://archive.globalfrp.org/evaluation/publications-resources/after-school-programs-in-the-21st-century-their-potential-and-what-it-takes-to-achieve-it (accessed July 17, 2020.)

- Kraft, M., and S. Dougherty. 2013. The effect of teacher–family communication on student engagement: Evidence from a randomized field experiment. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 6(3): 199-222. Available at: https://scholar.harvard.edu/mkraft/publications/effect-teacher-family-communication-student-engagement-evidence-randomized-field (accessed July 17, 2020).

- Resnick, M., P. Bearman, R. Blum, K. Bauman, K. Harris, J. Jones, J. Tabor, T. Beuhring, R. Sieving, M. Shew, M. Ireland, L. Bearinger, and J. Udry. 1997. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the national

longitudinal study on adolescent health. JAMA 278(10):823-832. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.278.10.823 - Sachdev, N. 2012. The Washington, D.C. high school dropout crisis. Available at: http://www.americangraduatedc.org/content/pdfs/AmGradDC_Gap_Analysis_2012.pdf (accessed September 10, 2015).

- Zimmerman, E., and S. H. Woolf. 2014. Understanding the relationship between education and health. Discussion Paper, Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC. Available at: http://nam.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2015/06/BPH-UnderstandingTheRelationship1.pdf (accessed September 10, 2015).