Integrating Research into Health Care Systems: Executives' Views

Background

In the United States, the notion of a continuously learning health care system is gaining traction as a way to advance the objectives of high-quality, patient-centered care at reasonable cost. One activity of a learning health care system is the conduct of applied research and ongoing quality improvement to continually generate actionable knowledge to improve health outcomes. The goal of accelerating the acquisition of actionable knowledge responsive to health care needs has led to several high-profile funding mechanisms. These mechanisms endeavor to both strengthen collaboration between researchers and health care systems, and to integrate research and practice as core elements of organizational commitment to improving the effectiveness of care. These mechanisms include the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) and the NIH Healthcare Systems Research Collaboratory. PCORnet is funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). It is designed to create an infrastructure to accelerate comparative effectiveness research that provides needed evidence to help patients and their caregivers make better-informed decisions. PCORnet has funded 29 research networks, including 11 Clinical Research Data Networks (CDRNs) and 18 Patient-Powered Research Networks (PPRNs), as well as a coordinating structure designed to engage health care systems and other stakeholders (Fleurence et al., 2014). The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Healthcare Systems Research Collaboratory, supported by the NIH Common Fund, is designed to support high-value practical research via pragmatic trials (Johnson et al., in press).

Research conducted in and with health care systems is not business as usual. Previous commentators have noted different priorities between health systems and most research studies (Alexander et al., 2007; Cosgrove et al., 2013; Danforth et al., 2013). But what do health care executives think of the value and challenges of integrating effectiveness research knowledge generation about what works best for whom as a core element of continuous care system improvement (see Box 1)? To begin to explore the prospects, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) with the support of PCORI held the first session of a two-session workshop April 23–24, 2014, titled “Health System Leaders Working Towards High-Value Care Through Integration of Care and Research.” The workshop was designed by a planning committee of IOM members, thought leaders in health care systems improvement, chief executives, and PCORI leaders. The first workshop was attended by a select group of individuals to discuss opportunities to use emerging data networks to create effective learning health care systems in which researchers could partner with stakeholders in health care systems (leaders, clinicians, patients, and others) to improve the experience and outcomes of care, increase access, and provide health care that is affordable. Those attending represented persons who lead networks being developed as part of PCORI’s PCORnet, newly formed CDRNs, and PPRNs along with systems leaders (C-suite leaders) from institutions that are sites of CDRNs. Members of the planning committee, PCORI leaders, a select group of nationally recognized thought leaders in systems improvement, and IOM staff also attended the first workshop.

Immediately following the first workshop, an online survey was sent to those attending the workshop to help plan the agenda for the second workshop. The second workshop was smaller and involved more discussion and interactive panels. This CEO-oriented workshop was built upon results of the first workshop and responses to the survey and was specifically directed to engage CEOs of leading academic and nonacademic delivery systems. Like the CDRNs and PPRNs that comprise networks involving all 50 states, attendance at the IOM workshops included persons representing all regions of the United States.

Survey and Responses

The PCORnet Health Systems Interaction & Sustainability Task Force, a group of PCORnet awardee representatives, suggested the survey. Task Force leaders at Group Health Research Institute developed the questions (see the Appendix) in consultation with IOM staff and a small group of PCORnet awardees and stakeholders.

The main theme of the survey was to explore the benefits and challenges of integrating research into practice from the perspective of C-suite leaders (chief medical officers, chief operations officers, CEOs, and other executives) and from the perspective of persons engaged in developing CDRNs and others attending the first IOM workshop. Meeting attendees were affiliated with PCORnet networks or other organizations known to be engaged in leveraging research and analytics for performance improvement, increased efficiency, and better care value; 62.8 percent responded and 47 percent of respondents (23) had a C-suite role such as chief medical officer or chief executive officer.

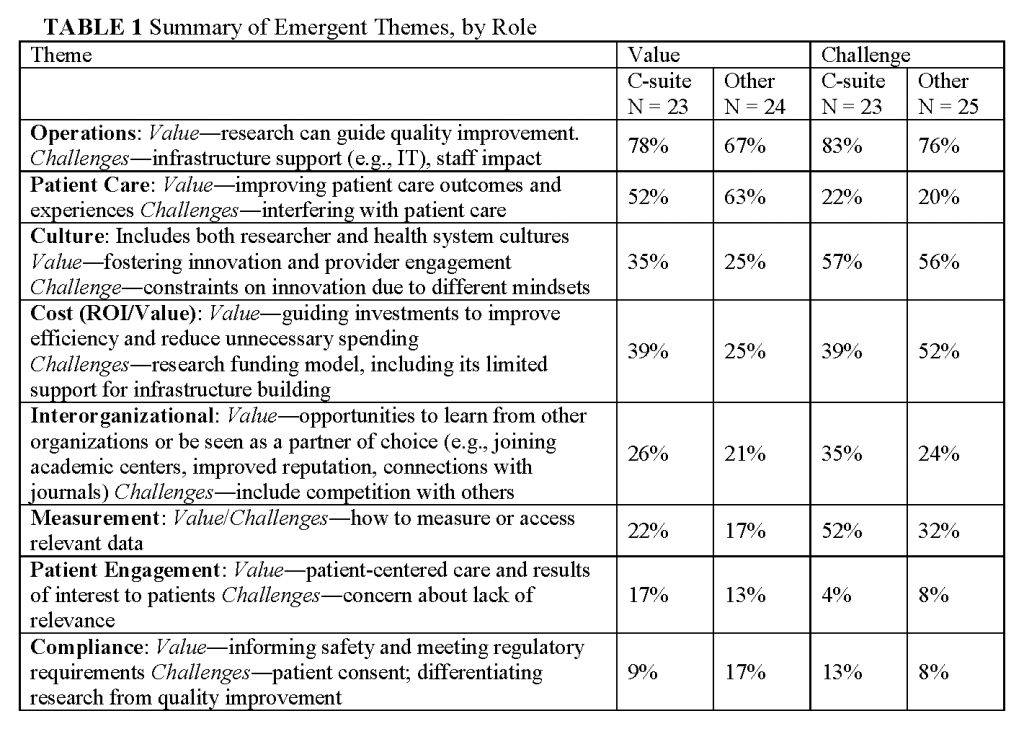

Our analysis of themes that emerged from the open-ended questions about facilitators and barriers is summarized in Table 1. It highlights the perspective among many respondents that while knowledge generation can add value, it also presents certain challenges.

Operations

The day-to-day work that health systems conduct, which we term operations, rose to the fore in framing both the perceived values (raised by 72 percent) and challenges (raised by 80 percent) of knowledge-generation activities. This work includes that conducted by leadership, financial and informatics departments, frontline clinicians, and clinic and hospital staff. Respondents viewed research as a way to guide and jump-start organizational quality improvement processes. For example, “Significant process improvements and operational changes are made on the basis of ongoing data analysis.” Additionally, operational needs can generate cutting-edge research questions. As one respondent stated, “Setting the agenda―organizational priorities should inform the research agenda.” This bi-directional flow of problems raised and solutions agreed upon is the ideal, and respondents shared their organizations’ successes. Incorporating knowledge generation into a complex structure arose as a major challenge. One reason raised is that research findings are not seen as addressing the needs of health systems. As one respondent wrote, “the value of well done research, while potentially tremendous, seems to be significantly out of synch with the needs of a health care system that is facing growing pressure and an ever-increasing pace of change.” For example, another respondent raised the challenge of how to “encourage and focus research activities in areas that have alignment with [accountable care organization] goals and which address major morbidities in our community.” Even when research findings do generate best practices, it is challenging to implement them in new locations and systems: “translating knowledge into action―including scale and spread―is a complex enterprise of its own.” Also raised as a critical challenge was the extra responsibility health systems staff may face with their organization’s participation in research at multiple levels, including leadership and IT, “staying focused and strategically aligning all of the moving parts.” Overall, there was consistency in the prominence of comments about operations made by executive and other respondents. However, C-suite respondents were more likely to state that knowledge generation could add value in this area (78 percent vs. 67percent) and to frame it in terms of alignment with organizational mission or priorities (70 percent compared to 46 percent): it “allows us to meet our Mission, which includes education and research while providing care to diverse populations.”

Patient Care

Improving patient care was a prominent way that knowledge-generating activities were perceived to add value; as noted by 52 percent of executives and 63 percent of other respondents. Ways that value is added include generating new evidence to improve decision making. Some (21 percent) respondents raised challenges in this area, including the difficulty in getting clinician or administrator buy-in and being able to put evidence into practice in a timely manner. At the same time, researchers may lack an understanding of the complexities of delivering care that is necessary for translating findings into practice. Research focused only on clinic-based interventions may miss the significant work other individuals contribute to care delivery: “Knowledge generation must include not only medical knowledge, but knowledge of care production (throughput, customer service, engagement of the patient, resource utilization).”

Culture

Many respondents (56 percent) brought up differing professional cultures between the fields of research and healthcare as a factor that can limit innovation and engagement, which manifest in a “tension between operationally focused learning versus more academically focused publishable projects.” For example, one respondent pointed out the challenge of “integration of values at staff levels―clinic staff appreciating value of research and having research staff understand needs of patient and clinic operations.” Amplifying the concerns that research may not be addressing health system needs, one respondent raised a concern that “traditional NIH-focused research will predominate and drown out the practice of patient-centered research.” Differing cultures can also limit the translation and sustainability of an intervention shown to be effective. As one executive wrote, “speed of transfer is somewhat reliant on the standardization of the generated knowledge, and the willingness of the care ecosystem to accept that standardization. While there are logistical challenges in this, the cultural challenges are greater.” It should be noted that health systems contain many cultures with differing viewpoints on what is most useful, further complicating what it takes to foster innovation and engagement. For example,

Most clinicians still want the ‘randomized trial’ as sufficient evidence that practice change is warranted when in fact quality improvement science can provide a platform for change much more quickly. Journal editors need to embrace that concept as well.

Even though culture was raised as a strong challenge, the concept of knowledge generation seemed to have traction as something that could span cultures, such as through generating physician engagement. Statements that framed knowledge generation as promoting a positive change in culture were given by 35 percent of C-suite respondents and 25 percent of others.

Return on investment

ROI “both in terms of quality and cost” were mentioned in many comments about challenges. The short time horizon for decision-making stood out as a challenge. Health systems need results “that can achieve a ‘good enough answer’ (that is, an answer good enough for a CEO or CFO to ‘bet’ large amounts of money) quickly enough to be actionable.” Nonexecutive respondents were more likely to bring up this topic (52 percent) than executives (39 percent). Comments by nonexecutives also addressed research funding models, especially for establishing infrastructure, for example,

Establishing a funding model that works for researchers and the organizations such that […] there is time and money for the researchers to publish the work in reputable journals, thereby making not just the specific delivery system a learning system, but the whole health care system.

The concept of return on investment also arose as a benefit, particularly as it pertains to wise resource use:

There is an opportunity for the new knowledge to drive increased value: quality and safety of the care itself and efficiencies that reduce the overall expense burden to the individual and society. The greater the value, the more our healthcare system is preferred by patients and payers.

Comments like this were somewhat more frequent from executives (39 percent) than other respondents (25 percent).

Inter-organizational relations

Respondents (23 percent) noted a number of ways in which knowledge generation activities can improve relations with other organizations, for example “adding reputational value,” sharing best practices, building networks of academic centers, and connecting with journals. Some challenges include competition with others in “an increasingly demanding market.”

Measurement

Technical aspects of measurement, in addition to using data to support operations, arose as another challenge, especially for executives (52 percent of their comments). Examples included restrictions on research use of certain clinical data and compilation of metrics that were not relevant for meeting analytic questions―both clinical measures that were not standardized for research and research measures that were not meaningful in practice. Knowledge generation activities were noted as a potential mechanism for improving measurement (20 percent), such that the right data could be obtained at the right time to answer a question of interest. One respondent noted that getting data integrated into routine care delivery is challenging but “If this challenge can be overcome then it would lead to an improved learning healthcare system; being able to build on data collected for both purposes/can be used for both purposes―adding value.” In particular, using data generated within the health system to measure outcomes was seen as beneficial for providing feedback to clinicians and to improving processes.

Patient engagement

Patient engagement was part of the value proposition (raised in 15 percent of comments) through creating care “that patients prefer,” and research results that matter to them―“knowledge for the patient.” Comments on the importance of patient engagement were prominent in the workshop and strongly endorsed repeatedly by leaders and other participants. The survey reinforced that leaders see patient engagement as part of the definition of value.

Compliance

Comments were coded into this theme if they related to informing safety and meeting regulatory requirements. This theme arose in a small number of comments, roughly equally in comments about value (13 percent) and challenges (11 percent). Challenges noted include patient consent and the need for more clarity about how to navigate the ambiguous application of research regulations to learning health care system activities. The fact that compliance issues were not raised more prominently is intriguing, given that the sometimes ambiguous distinction between research and quality improvement, and attendant individual consent requirements, is attracting much attention in the research community. One possible explanation is that leaders see integrated research as part of a continuum of efforts to achieve quality, cost control and customer service. Another possible explanation is that meeting regulatory requirement is so central to leadership that the survey respondents did not consider it noteworthy in the context of our survey.

Observations and Follow-Up

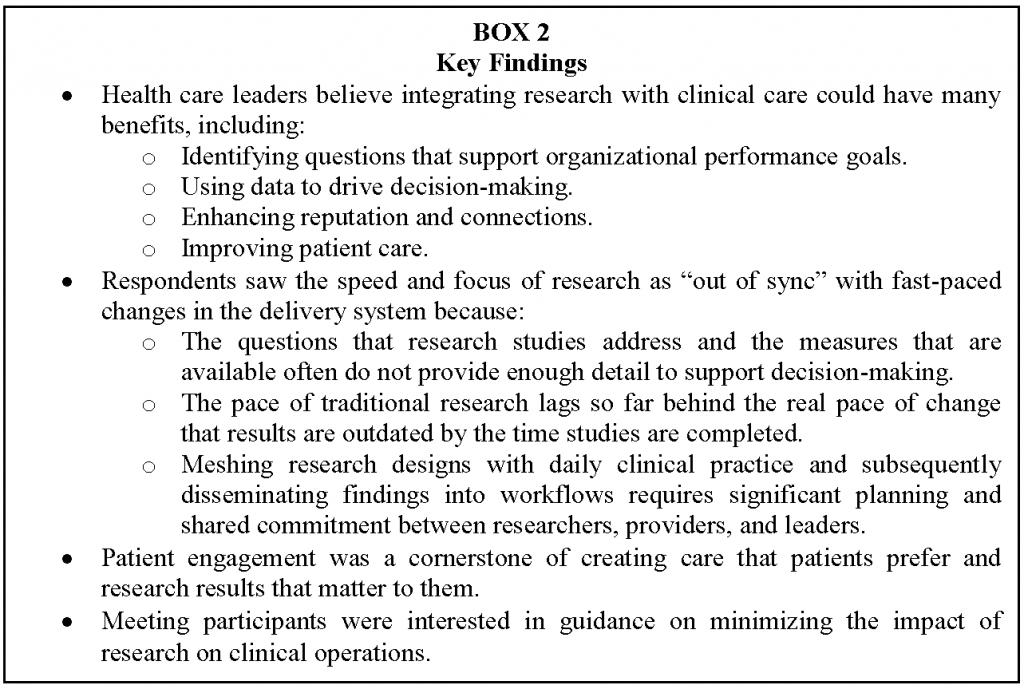

Given the reputations of the organizations invited to attend the meeting, these findings reflect the viewpoints of aspirational early adopters. However, they are concordant with previous findings (Alexander et al., 2007; Cosgrove et al., 2013; Danforth et al., 2013), and they provide valuable insights about meaningful incentives and operational enablers for integrating knowledge generation into care. With respect to the aim in drawing knowledge generation as a more integral component of medical practice, conclusions from this sample include general enthusiasm for the opportunity that data networks offer to learn from ongoing clinical work, especially as it offers a return on the immense investments systems have made in health information technology balanced against concerns that the pace of research is “out of sync” with demands of health care systems and a sense that topics of interest to researchers do not map well with needs of systems to improve access, improve quality and reduce rising costs. These also suggest that follow-up activities to improve insights and inform strategies and activities on the key pressure points and levers might include development of both local and national processes where researchers and delivery systems can meet, share ideas, and establish priorities for research projects, reduce challenges of growing research in delivery systems, and establish processes for translation of results into practice, thereby eliminate the current silos separating researchers and delivery system leaders. A cross-cutting theme that emerged throughout the categories, listed in Box 2, was that the knowledge generation that supports a learning health care system may be different in terms of objectives and methods from how either research or quality improvement is typically understood. For example,

Research of this kind should be undertaken as the result of a disciplined organizational process that sets priorities and links the value of the research back to the mission of the organization. In addition, knowledge generation around the ‘science of execution’ is a critical component of the knowledge needed for organizations that desire to be high performing and competitive in the marketplace.

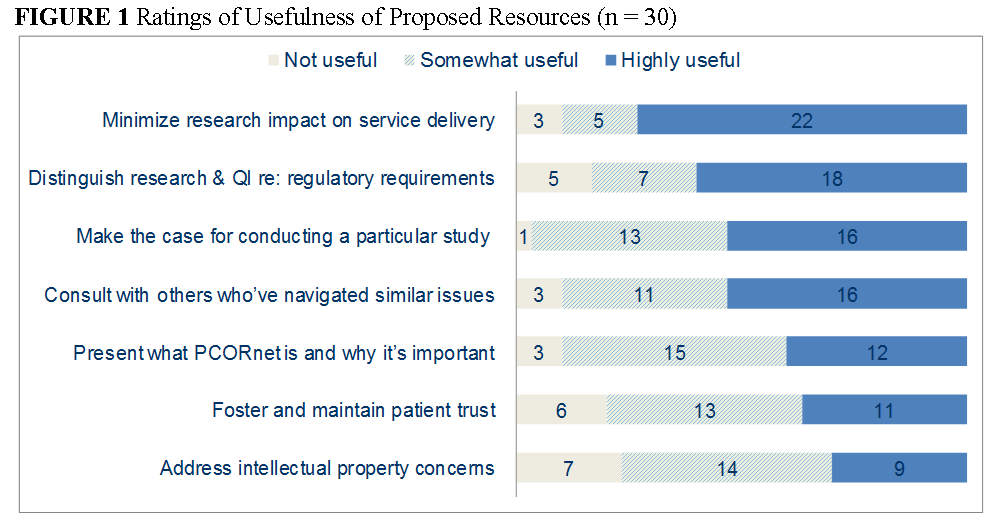

Therefore, building the capacity for continuous insights on the care most effective under different patient circumstances requires that research priorities and processes involve a meaningful partnership between patients and families, health system leaders, quality personnel, and researchers. The findings pointed to a number of ways to enhance the creation of this new approach to a learning health care system. Figure 1 summarizes how respondents rated the usefulness of resources that the PCORnet HSIS Task Force proposed to develop. Respondents rated all of the proposed resources as either somewhat or highly useful. The items that were rated the highest were guidance on minimizing the impact on service delivery, understanding research and quality improvement regulatory requirements, making the case for conducting a particular study, and consulting with others who have navigated similar issues.

Our findings will be used alongside other work by the IOM’s Roundtable on Value & ScienceDriven Health Care and by PCORI to inform the methods and value proposition for linking research and practice as common contributors in advancing the effectiveness, quality, and patient-centeredness of care at a reasonable cost in the United States. In particular, PCORnet will use this information in its infrastructure-building work in areas including health systems interactions, data standards, clinical trials, and ethics. The IOM is disseminating this discussion paper to make the results of the survey available to a wider audience.

Appendix

Survey instrument and procedures

We asked three sets of questions. First, we asked the respondents’ role. The response options included health care executive (C-suite) roles such as chief medical officer, roles of other expected meeting attendees such as researcher, and a write-in option. Respondents were instructed to select all applicable roles.

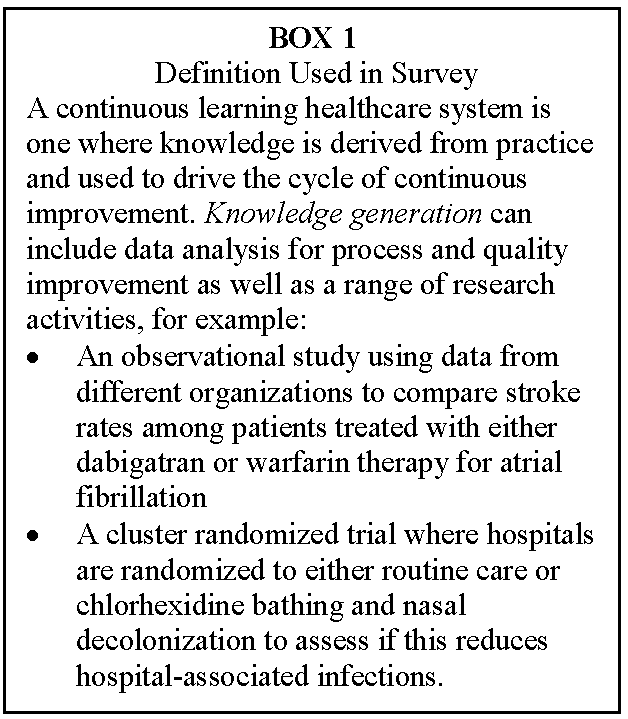

Second, we asked respondents open-ended questions about their perspectives on the value, barriers, and challenges of conducting what we termed knowledge-generation activities in their organization. To orient the respondent to a common definition building on the IOM meeting themes, we provided the following definition:

A continuous learning healthcare system is one where knowledge is derived from practice and used to drive the cycle of continuous improvement. Knowledge generation can include data analysis for process improvement as well as a range of research activities, for example:

- An observational study using data from different organizations to compare stroke rates among patients treated with either dabigatran or warfarin therapy for atrial fibrillation

- A cluster randomized trial where hospitals are randomized to either routine care or chlorhexidine bathing and nasal decolonization to assess if this reduces hospital-associated infections

Third, for attendees affiliated with PCORnet CDRNs or PPRNs, we asked which network(s) their organization belonged to. We also asked them about the utility of a set of proposed resources to support the integration of research activities into clinical settings, such as using cases of integrating a research study into a clinical setting without undue impact on workflow.

We sent the questionnaire to 79 meeting attendees. We excluded meeting organizers and representatives of partner organizations such as government agencies. We emailed a request to complete the survey to the invitees at the conclusion of the meeting. We sent up to four reminder emails. To reduce burden, additional questions regarding potential PCORnet resources were not included in the third and fourth reminders. Forty-nine attendees responded, and one indicated that they had not attended the meeting (response rate 62.8 percent). Of the respondents, 47 percent had a C-suite role. The other respondents included researchers (11), deans and research directors/vice presidents (14), operational VPs and directors (6), and other (2). All 11 CDRNs and 4 PPRNs were represented. Eight respondents did not know if they were affiliated with a PPRN, so it is possible that additional PPRNs were represented.

We summarized the responses to the questions about role, PCORnet affiliation, and perceived usefulness of potential resources using descriptive statistics. To analyze the responses to open-ended questions about the value and barriers or challenge of integrating knowledge generation and value into a health care organization, three authors (KJ, JA, KN) reviewed independently all responses received after the second reminder and developed categories of emergent themes. After discussing the proposed themes, we agreed on 11 themes to use for coding. Two team members then independently coded all responses. Each quote could be coded into more than one theme. A third member then summarized the results, looking closely at items coded by only one coder and noting any individual quotes that did not seem to fit with the coding scheme for discussion and consensus. Through this process, as well as discussion of the overall preliminary themes with the HSIS Task Force, we finalized the category descriptions and the coding of responses into categories.

References

- Alexander, J. A., L. R. Hearld, H. J. Jiang, and I. Fraser. 2007. Increasing the relevance of research to health care managers: Hospital CEO imperatives for improving quality and lowering costs. Health Care Management Review 32(2):150–159. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HMR.0000267792.09686.e3

- Cosgrove, D. M., M. Fisher, P. Gabow, G. Gottlieb, G. C. Halvorson, B. C. James, G. S. Kaplan, J. B. Perlin, R. Petzel, G. D. Steele, and J. S. Toussaint. 2013. Ten strategies to lower costs, improve quality, and engage patients: The view from leading health system CEOs. Health Affairs 32(2):321–327. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1074

- Danforth, K. N., C. D. Patnode, T. J. Kapka, M. G. Butler, B. Collins, A. Compton-Phillips, R. J. Baxter, J. Weissberg, E. A. McGlynn, and E. P. Whitlock. 2013. Comparative effectiveness topics from a large, integrated delivery system. Permanente Journal 17(4):4–13. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/13-036

- Fleurence, R. L., L. H. Curtis, R. M. Califf, R. Platt, J. V. Selby, and J. S. Brown. 2014. Launching PCORnet, a national patient-centered clinical research network. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 21(4):578–582. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002747

- Johnson, K., C. Tachibana, G. D. Coronado, L. M. Dember, R. E. Glasgow, S. S. Huang, P. J. Martin, J. Richards, G. Rosenthal, E. Septimus, G. E. Simon, L. Solberg, J. Suls, E. Thompson, and E. B. Larson. 2014. A guide to research partnerships for pragmatic clinical trials. British Medical Journal 349 (g6826). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g6826