Community Health Needs Assessments? Aligning the Interests of Public Health and the Health Care Delivery System to Improve Population Health

Recognizing the challenges of improving health outcomes depends on a complex set of factors, many beyond the control of the health care system, a recent report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) stresses the importance of population health measurement to ensure accountability to improve the quality of health care as well as population health outcomes (IOM, 2013). Noting that an unprecedented wealth of health data is providing new opportunities to understand and address community-level concerns, the IOM argues that the sharing and collaborative use of data and analysis is essential for the integration of primary care and public health in the interest of population health (IOM, 2012). Several discussion papers call for new approaches to population health measurement (Auerbach et al., 2013; Hester, 2013; Shortell, 2013). Stoto (2014) addresses these measurement issues more completely, applying performance measurement concepts in a variety of population health settings.

In this context, the Affordable Care Act requirement that not-for-profit hospitals conduct community health needs assessments (CHNAs) and adopt implementation strategies has the potential for coordinating the efforts of the health care delivery sector, public health agencies, and other community organizations to improve population health outcomes (Stoto, 2013). Intended to leverage the “community benefits” that hospitals are required to provide in lieu of taxes, all not-for-profit hospitals are required to work with public health agencies and other organizations to conduct a CHNA at least every three years and adopt an implementation strategy describing how identified needs will be addressed (Rosenbaum, 2013). By aligning and leveraging the efforts and resources of the health care delivery sector, public health agencies, and other community organizations, the new CHNA requirements create a shared interest in improving population health (Stoto, 2013).

The new CHNA requirements, along with other developments discussed below, help create a mandate for a shared population health measurement system. In their synthesis of effective means of achieving “collective impact,” Kania and Kramer (2011) conclude that a “shared measurement system” is one of the five conditions necessary for large-scale social change. Collecting data and measuring results consistently on a short list of indicators at the community level and across all participating organizations not only ensures that efforts remain aligned but also enables the participants to hold each other accountable and learn from each other’s successes and failures. As quality measurement did in health care, performance measurement has the potential to transform population health.

But without a clear sense of purpose and an appropriate framework, existing population health measures will not fulfill this potential. Population health measures help to set priorities and monitor how well we are managing a responsibility that the health care delivery system and many other entities in the community all share. Managing a shared responsibility, however, is challenging: given the many factors that influence health, no single entity can be held accountable for health outcomes. Moreover, the populations served by health care systems generally do not coincide with counties or other geopolitical boundaries that define health department responsibilities. To address these challenges, in this essay we review the Affordable Care Act CHNA requirements and survey existing population health measurement efforts. Building on modern health care performance measurement methods, we propose a distinction between two different types of measures that (1) address the shared responsibility for population health and (2) hold accountable the health care delivery systems, health departments, and other community groups for the actions they individually take to achieve population health goals. One approach to the first set of measures is illustrated with an example from Montgomery County, Maryland. The second measurement need is illustrated with a hypothetical example about a community’s approach to addressing tobacco and health. We conclude with suggestions for implementing these ideas to align public health and health care delivery system efforts in communities to improve population health.

Community Benefits and Community Health Needs Assessments

Not-for-profit hospitals, in exchange for their exemption from most taxes, have long been required to give back to the communities they serve. In 2008, the total value of hospitals’ “community benefits” under federal, state, and local law was estimated at $12.6 billion. Hospitals originally met this obligation primarily by providing uncompensated care but, since 1969, have also included other activities that would benefit their communities, such as health promotion programs, research, and education (Rosenbaum, 2013). Despite this change, most community benefits continue to be devoted to patient care. In a national study, Young and colleagues (2013) found that in fiscal year 2009, nonprofit hospitals reported an average of 7.5 percent of their operating expenses spent on community benefits, with most expenditures for subsidized, or charity care. Only about 5 percent of benefits provided were devoted to “community health improvements.”

As mandated by the Affordable Care Act, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) now requires that all not-for-profit hospitals conduct CHNAs in conjunction with local health departments and others. CHNAs must identify existing health care resources and prioritize community health needs. Hospitals also must develop an implementation strategy to meet the needs identified through it and a set of performance measures to track progress. In preparing these reports, hospitals are expected to take into account input from individuals who represent the broad interests of the community served, including those with special knowledge of or expertise in public health. At a minimum, hospitals must consult with “at least one state, local, tribal or regional governmental public health department with knowledge, information, or expertise relevant to the health needs of the community” (Rosenbaum, 2013).

These requirements are mirrored in the Public Health Accreditation Board’s (PHAB) standard mandating that health departments participate in or conduct a collaborative process resulting in a comprehensive community health assessment. Other PHAB standards require that health departments conduct a comprehensive planning process resulting in a “community health improvement plan,” assess health care service capacity, identify and implement strategies to improve access to health care, and use a performance management system to monitor achievement of objectives (PHAB, 2014). The similar requirements from PHAB and the IRS provide an opportunity to catalyze stronger collaboration and better shared measurement systems among hospitals and health departments.

At the same time, other initiatives also contribute to the need for shared population health measurement systems. Focusing on implementing the “Triple Aim” in accountable care organizations, for instance, Hacker and Walker (2013) call for a broader “community health” definition that could improve relationships between clinical delivery and public health systems and health outcomes for communities. Addressing similar issues, Gourevitch and colleagues (2012) suggest potential innovations that could allow urban accountable care organizations to accept accountability, and rewards, for measurably improving population health.

Primarily because of the new IRS requirements, organizations such as the Catholic Health Association of the United States (2013), the Association for Community Health Improvement (2014), Community Commons (2014), and the Healthy Communities Institute (2014) have developed CHNA toolkits or systems. However, despite such guidance, implementation of this mandate in hospitals and communities varies markedly, and there is a strong need to further develop and refine methods to use CHNAs to catalyze and coordinate hospitals’, public health agencies’, and other organizations’ community health improvement activities (Healthy Communities Institute, 2014).

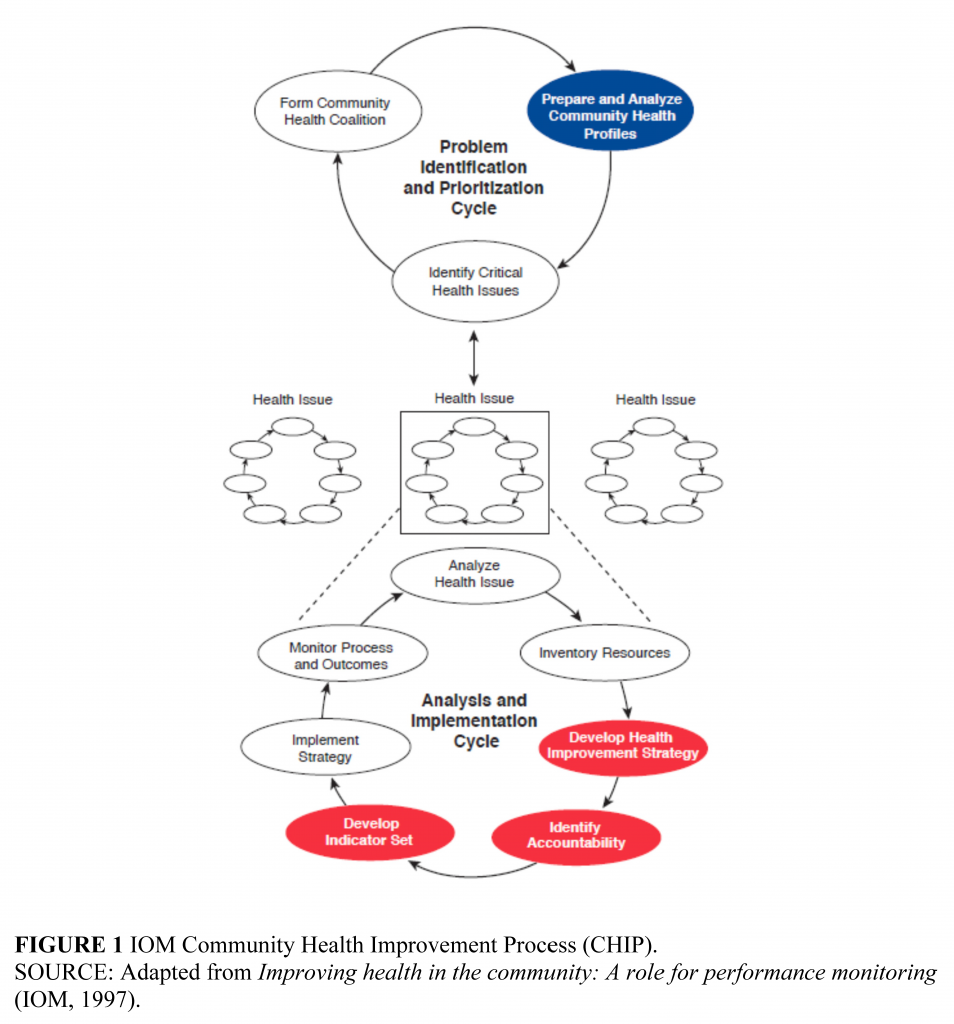

One barrier to implementation of CHNAs may be a lack of clarity and general agreement about what should be measured. Given the many factors that influence health, no single entity can be held accountable for health outcomes, and neither hospitals nor health departments want to publish indicators that they cannot influence by their activities. A solution can be found in the 1997 Institute of Medicine report Improving Health in the Community (IOM, 1997). The Community Health Improvement Process (CHIP) proposed by that report, summarized in Figure 1, calls for two different kinds of measures. The first is a community health profile to identify priorities; the second is a set of valid and actionable performance measures keyed to an improvement strategy to ensure the accountability of the hospitals, health departments, and other entities that contribute to that strategy.

Community Health Profile

First, to coordinate a community’s efforts, a community health profile is needed to summarize a community’s overall health status, for which public health agencies, health care providers, and many other community stakeholders share responsibility. The community health profile in the IOM model – another term for a CHNA or CHA – is highlighted in the “Problem Identification and Prioritization Cycle” section of Figure 1. This profile is used to identify specific health problems or issues where concerted action by different entities in the community (public health, health care providers, employers, schools, and so on) is needed.

Because the profile is used to set priorities, it should focus on outcome measures, including health behaviors, access to care, and other determinants of health. The set of measures in the profile should be limited in number otherwise users lose sight of the big picture—but yet comprehensive enough to cover all the important issues, including the determinants as well as health outcomes. Composite measures such as indicators of preventable chronic disease mortality can be useful in this context. The individual measures in the set must be coherent so that they work together to tell the community’s health story, yet be significant enough to gain policy makers’ attention. If the measures cannot be monitored over time, they are not very useful for tracking progress so that adjustments can be made in population health improvement plans. The measures also need to relate to the community in question and be capable of being disaggregated to identify disparities within that population; the latter creates problems for less-populous communities (Stoto, 2005).

Once a community has constructed a population health profile, that profile can be used to identify areas for particular focus in health improvement activities. Priorities could be based on benchmarking with other jurisdictions in the state or with similar counties nationally, whether trends are going in the wrong direction, issues for which there are large disparities, or other community concerns.

Because benchmarking and other comparisons can help to identify priorities, a standard set of measures such as those developed for every county in the United States by the County Health Rankings project (University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2014) is a useful starting point. Based on the latest publicly available data for every county in the United States, the County Health Rankings measures collectively describe a community’s health in terms of health outcomes and five categories of health determinants or factors. The Health Outcomes category includes a measure of premature death and four measures of quality of life. The Health Behaviors category includes measures of tobacco use, diet and exercise, alcohol and drug use, and sexual activity. Clinical Care is assessed in terms of both access and quality. Social and Economic Factors such as education, employment, income, family and social support, and community safety are also included. The final health factors category includes measures of air and water quality and housing and transit to assess a community’s Physical Environment. In order to rank the counties in each state, an overall Health Outcomes summary score is created as an equally weighted composite of the mortality and quality-of-life measures, and an overall Health Factors summary score is a weighted composite of the other four components. Individuals more interested in specific aspects of a community’s health, perhaps because they are using the data as part of a CHNA, can use the six summary measures, or even the 27 underlying specific measures, in their analysis.

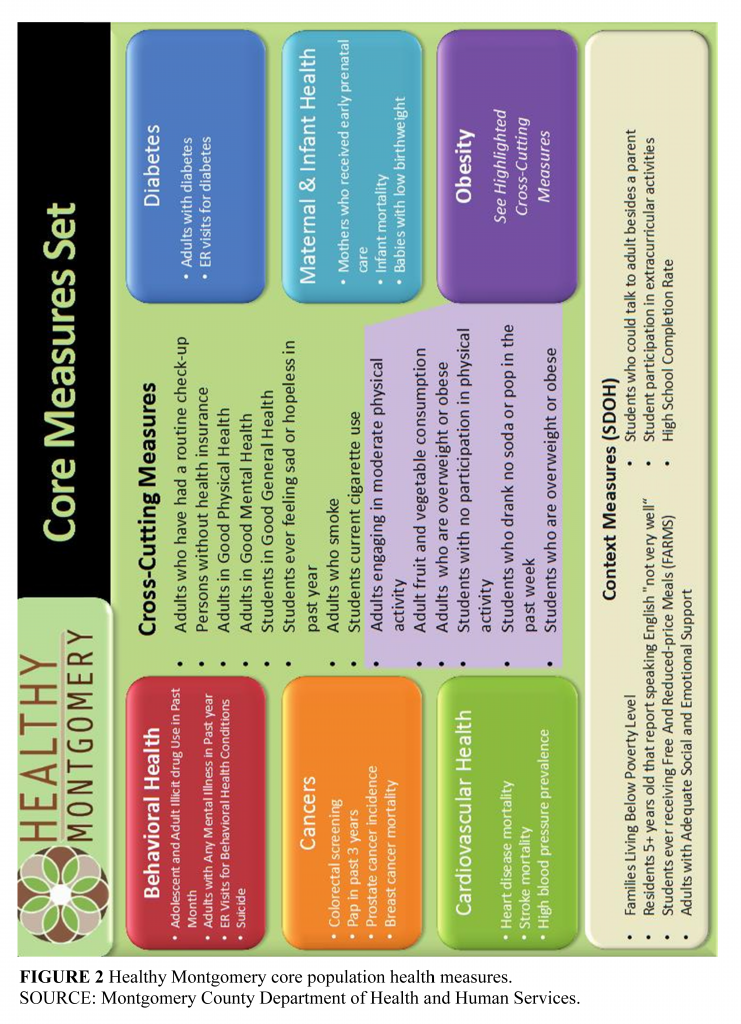

Communities that have been engaged in health improvement efforts for some time might want to go beyond these basic indicators to develop a community health profile more tailored to ongoing efforts. For example, Healthy Montgomery is a community health improvement process that seeks to achieve optimal population health and well-being for the residents of Montgomery County, Maryland. The county’s Department of Health and Human Services, all five not-for-profit hospitals located in the county, the Primary Care Coalition of Montgomery County (representing safety-net clinics), other health care providers, government agencies (including the school system, land-use planning agency, and recreation department), and community organizations all participate in an ongoing community-driven process to identify and address key priority areas. Six priorities have already been identified (behavioral health, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancers, and maternal and infant health) as well as three “lenses” (lack of access, health inequities, and unhealthy behaviors) through which to address them. To guide ongoing activities, the Healthy Montgomery steering committee recently adopted a set of 37 core measures that can be monitored over time and disaggregated to the relevant social units. Measures include behaviors, health determinants as well as health outcomes and address the concerns of the hospitals and represent existing Healthy Montgomery priority areas. These measures (Figure 2) were also chosen to reflect existing disparities and inequities as well as focus on areas where there is a potential for improvement, i.e., because Montgomery County ranks below the state or national averages, there are factors susceptible to health sector or population-based interventions, and/or the areas identified are matters of community concern (Svigos et al., 2014).

Performance Measures to Ensure Accountability

Careful consideration of all the factors represented in such community health profiles reminds us that population health must be seen as the shared responsibility of health care providers, governmental public health agencies, and many other community institutions. The challenge of managing a shared responsibility for the community’s health, however, is that given the broad range of factors that determine health, no single entity can be held accountable for health outcomes. To manage this shared responsibility, communities should develop a set of valid and actionable performance measures to ensure that the entities are held accountable for their activities (IOM, 2010). Identifying accountability for specific actions is an essential component of both the community health improvement plan required by the IRS and the comprehensive planning process in the PHAB standards. The IOM CHIP model includes the highlighted “indicator set” in the “Analysis and Implementation Cycle” (see Figure 1). Because these measures focus on what hospitals, health departments, and other entities do within their area of control, process measures and perhaps risk-adjusted health outcomes are the most appropriate form of measures.

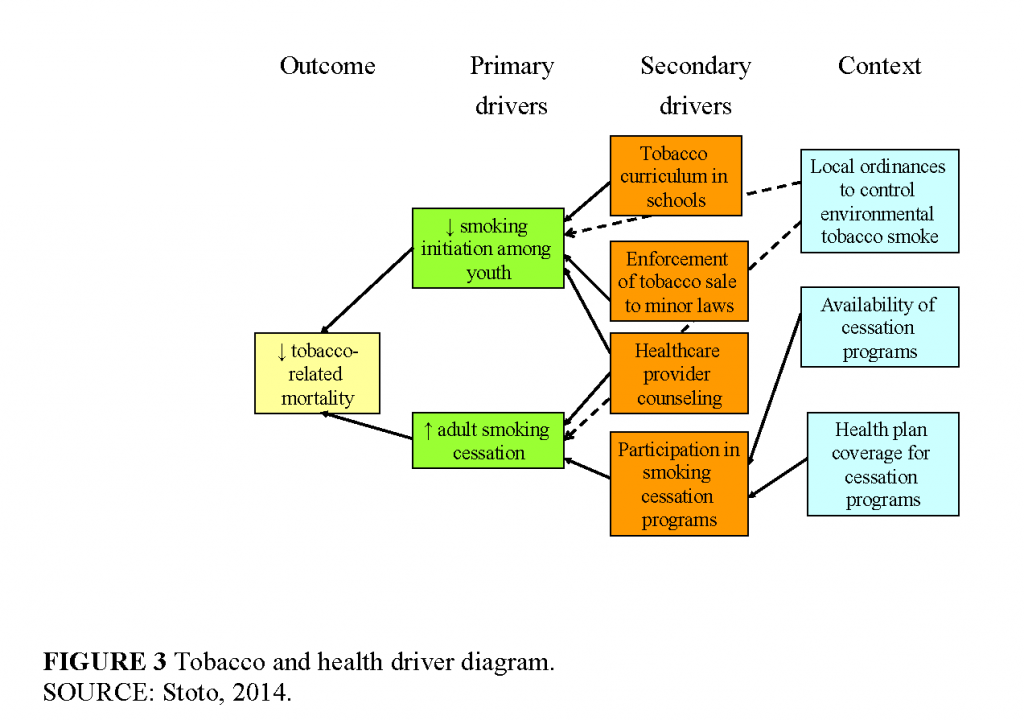

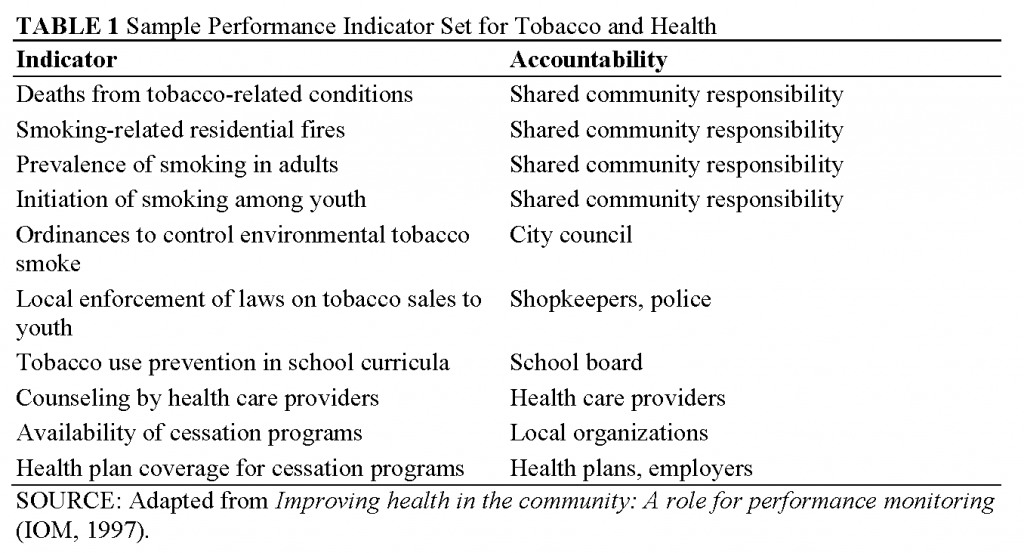

For example, consider the following sample performance indicator set, drawn from Improving Health in the Community (IOM, 1997). It starts from the point where a community has chosen to focus on tobacco and health issues. Figure 3 is a simplified “driver diagram” that illustrates the primary and secondary drivers of the main outcome—tobacco-related mortality—as well as the process changes or interventions needed to bring these forces into alignment in a community. The corresponding measures are summarized in Table 1.

A community taking this approach would want to monitor tobacco-attributable mortality, which can be estimated even in small communities using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Smoking-Attributable Mortality, Morbidity, and Economic Costs program data (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Tobacco-related mortality is useful to monitor to remind the community of the importance of the problem, but because of a long latency period for cancer and other outcomes, this measure is not a good indicator of the impact of current prevention initiatives. Monitoring smoking-related residential fires can complement this as a more timely outcome. Although the number of such fires in any community will be small, they can call attention to the problem by serving as sentinel events.

As intermediate outcomes, or as drivers of tobacco-related mortality, both the initiation of smoking among youth and the prevalence of smoking in adults (to assess the cumulative effect of cessation, which is more difficult to measure directly) should be measured. All of the indicators discussed to this point, however, measure how well the community as a whole is doing on its goal. The following set of measures serves to assess the contributions of specific stakeholders.

A measure of the prevalence or strength of ordinances to control environmental tobacco smoke, for instance, can hold local lawmakers responsible for passing legislation that, over the long run, can influence both smoking initiation and cessation in adults. Similarly, because national laws control tobacco sales to youth, measures of local enforcement of laws on tobacco sales to youth can represent the efforts of local merchants and law enforcement officials to address the problem in the community. Measures of the existence or the extent of tobacco prevention curricula in schools can serve as an indication of the school board’s commitment to addressing tobacco problems in the community.

More directly addressing the health care community, a measure of the extent to which providers counsel their patients about smoking cessation can serve to hold providers accountable for this effort. In any given community, groups such as the American Cancer Society or the American Lung Association, local health departments, hospitals. or employers can commit to providing smoking cessation programs. A measure of the availability of these programs in the community reflects those commitments. Finally, the measures include an indicator of health plan coverage for cessation programs measures the commitment of those who purchase health insurance—primarily employers—to ensure that these programs are included. With the mandatory inclusion of prevention programs under the Affordable Care Act, this measure is no longer necessary.

Implementation

The Healthy Montgomery effort described above provides an example of one way that a coordinated CHNA and implementation strategies can help to align population health efforts in a community. First, each of the county hospitals prepares its own CHNA as required by the IRS, but uses Healthy Montgomery community health data and priorities as a starting point. Second, each hospital develops an individual implementation strategy, building on its own mission and overall strategy, but coordinated with Healthy Montgomery priorities.

For example, Holy Cross Hospital and its onsite obstetrics/gynecology outpatient clinic for uninsured women serve patients in Montgomery County and other neighboring jurisdictions. Its CHNA describes an approach to community benefit that targets the intersection of documented unmet community health needs and the organization’s key strengths and mission commitments. The hospital’s mission is “outreach that improves health status and access for underserved and vulnerable,” and its strategic priorities include seniors and women and infants (Holy Cross Hospital, 2012). The Holy Cross implementation strategy addresses each of the six Healthy Montgomery priorities and “lenses.” For instance, with respect to the obesity priority area, specific community clinics as well as the hospital’s obstetrics/gynecology clinic are identified to address the “lack of access” lens. Regarding the health inequities lens, the implementation strategy addresses the hospital’s focus on obesity in pregnancy programs in its obstetrics/gynecology, perinatal services, and community clinics. And for the unhealthy behaviors lens, a community fitness program, Kids Fit, is described. Semiannual fitness assessments and the number enrolled in obesity in pregnancy programs are the performance measures for these programs. Other hospitals have their own implementation strategy and performance measures, and a countywide obesity strategy that incorporates the schools and other entities is under development. This two-stage approach—a countywide CHNA with priorities based on a community health profile, with separate CHNAs, implementation strategies, and performance measures for each hospital (as well as other organizations)—solves two problems that have been challenges for both hospitals and health departments. First, hospital service areas are often not coincident with county or other geopolitical boundaries. This approach allows hospitals to develop needs assessments and implementation plans for the populations they serve that are substantively coordinated with the needs of the larger communities in which they are situated. Second, hospitals are reluctant to be held accountable for population health outcomes over which they have little control. Hospital-specific implementation strategies and related performance measures, focused on activities consistent with the hospitals’ mission and strategic goals, provide a means of aligning these activities with overall community health priorities.

Conclusion

Because the new IRS CHNA requirement leads communities toward developing a shared measurement system, it represents an important opportunity to align and leverage the interests of the efforts and resources of the health care delivery sector, public health agencies, and other community organizations to improve population health. However, because of the lack of clarity and general agreement about what should be measured, it is a missed opportunity in many communities.

To help fulfill the potential of the CHNA regulations, we suggest that two different types of measures are needed. The first set of measures is a community health profile to monitor the responsibility for population health that all share and to help identify priorities. These measures should focus on health outcomes and be geographically based, at the county level for instance, to provide a clear opportunity for health departments to collaborate with hospitals in identifying community health needs. The second set of measures should focus on performance of agreed-on program activities, ensuring accountability for the actions hospitals and other organizations take individually to achieve population health goals. As long as the focus of these activities is aligned with an evidence-based overall community health improvement strategy in which hospitals, health departments, and other organizations contribute according to their interests and strengths, these indicators can include process measures and be tailored to the target populations that each of these entities serve.

References

- Association for Community Health Improvement. 2014. Community health assessment toolkit. Available at: http://www.assesstoolkit.org/ (accessed June 28, 2014).

- Auerbach, J., D. I. Chang, J. Hester, and S. Magnan. 2013. Opportunity knocks: Population health in State Innovation Models. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201308d

- Catholic Health Association of the United States. 2013. Assessing and addressing community health needs. Available at: http://www.chausa.org/docs/default-source/general-files/cb_assessingaddressingpdf.pdf?sfvrsn=4 (accessed June 28, 2014).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008. Smoking-Attributable Mortality, Morbidity, and Economic Costs (SAMMEC) program. Available at: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/sammec/about_sammec.asp (accessed June 28, 2014).

- Community Commons. 2014. Advancing the movement. Available at: http://www.advancingthemovement.org/how.aspx (accessed June 28, 2014).

- Gourevitch, M. N., T. Cannell, J. I. Boufford, and C. Summers. 2012. The challenge of attribution: Responsibility for population health in the context of accountable care. American Journal of Public Health 102(Suppl 3):S322–S324. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300642

- Hacker, K., and D. K. Walker. 2013. Achieving population health in accountable care organizations. American Journal of Public Health 103(7):1163–1167. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301254

- Healthy Communities Institute. 2014. Supporting partnerships to drive community improvement. Available at: http://www.healthycommunitiesinstitute.com/consortiums-and-coalitions-solutions/ (accessed June 28, 2014).

- Hester, J. A. 2013. Paying for population health: A view of the opportunity and challenges in health care reform. NAM Perspectives. Commentary, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201309c

- Holy Cross Hospital. 2012. Fiscal 2013 community benefit implementation strategy multi-year community benefit “strategic action” plan. Available at: http://www.holycrosshealth.org/documents/community_involvement/HCH_CommunityBenefitImplementationStrategy_FY13.pdf (accessed June 28, 2014).

-

Institute of Medicine. 1997. Improving Health in the Community: A Role for Performance Monitoring. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/5298

-

Institute of Medicine. 2011. For the Public’s Health: The Role of Measurement in Action and Accountability. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13005

- Institute of Medicine. 2012. Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13381

-

Institute of Medicine. 2013. Observational Studies in a Learning Health System: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18438

- Kania, J., and M. Kramer. 2011. Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review 9(1):36–41. Available at: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/collective_impact# (accessed June 24, 2020).

- PHAB (Public Health Accreditation Board). 2013. Standards and measures, version 1.5. Available at: http://www.phaboard.org/wp-content/uploads/SM-Version-1.5-Board-adopted-FINAL-01-24-2014.docx.pdf (accessed June 28, 2014).

- Rosenbaum, S. 2013. Update: Treasury/IRS proposed rule on community benefit obligations of nonprofit hospitals. Available at: http://www.healthreformgps.org/resources/update-treasuryirs-proposed-rule-oncommunity-benefit-obligations-of-nonprofit-hospitals/ (accessed June 28, 2014).

- Shortell, S. M. 2013. A Bold Proposal for Advancing Population Health. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201308a

- Stoto, M. A. 2005. Population health monitoring. In Health statistics: Shaping health policy and practice, edited by D. J. Friedman, E. L. Hunter, and R. G. Parrish. New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 317–339.

- Stoto, M. A. 2013. Population health in the Affordable Care Act era. AcademyHealth. Issue Brief. Available at: http://www.academyhealth.org/files/AH_2013%20Population%20Health%20final.pdf (accessed June 28, 2014).

- Stoto, M. A. 2014. Population health measurement: Applying performance measurement concepts in population health settings,” eGEMs (Generating Evidence & Methods to improve patient outcomes): Vol. 2: Iss. 4, Article 6. Available at: http://repository.academyhealth.org/egems/vol2/iss4/6 (accessed April 3, 2015).

- Svigos, F., C. Ryan-Smith, A. Udelson, C. Erickson, S. Rahman, and M. A. Stoto. 2014. Healthy Montgomery: Developing community health indicators to catalyze change and improve population health. Poster presented at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting, San Diego, CA.

- University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. 2014. County health rankings and roadmaps, 2014. Available at: www.countyhealthrankings.org (accessed June 28, 2014).

- Young, G. J., C. H. Chou, J. Alexander, S. Y. Lee, and E. Raver. 2013. Provision of community benefits by tax-exempt U.S. hospitals. New England Journal of Medicine 68(16):1519–1527. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1210239