The Power of Youth in Improving Community Conditions for Health

Though a common target for health-improving efforts, young people are not often regarded as agents of change for healthier communities. However, a growing number of successful health-supportive policy, environment, and systems-change efforts trace their impetus to youth involvement. Not only are youth proving to be catalysts and prolific communicators in social movements, but their involvement signals a potential for career choices and civic stewardship that portends improving population health and equity in the years to come. An emerging area of research is beginning to show that youth organizing can contribute to both community development and youth development (Ginwright and James, 2002; Christens and Kirschner, 2011). This discussion paper examines promising models of youth involvement in social movements for better community health, some of which recently came to the attention of the Roundtable on Improving Population Health.

On Community and the Potential of Youth

Health does not just happen in hospitals and doctors’ offices. We know that health, in the broad sense, also happens in the places where people live, work, learn, and play. Making health happen in nonmedical settings is largely dependent on the contributions of people working on behalf of communities, including elected officials and community leaders. Organizing community residents has become an increasingly common approach to promoting the health of the public, or population health.

Community organizing motivates and prepares community members to identify shared problems and to work collectively toward solutions. Community organizing may focus on health improvement for reasons both ethical (e.g., “nothing about me without me”) and practical (e.g., communities have essential knowledge and assets not available from outside experts). Common targets for community organizing for health include HIV/ AIDS prevention, childhood obesity prevention, health care reform, and mental health services. This discussion paper focuses on community organizing to improve health that involves youth.

“Youth organizing is a process for developing within a neighborhood or community a base of young people committed to altering power relationships and creating meaningful institutional change” (Sullivan et. al., 2003). Projects aiming for the greatest impact on population health in low-income communities and communities of color necessarily focus on the upstream social determinants of health and often engage youth in advancing policy and systems change strategies. Youth are vital to the cause because they live the everyday reality of their neighborhoods, are knowledgeable of the community’s strengths and vulnerabilities, and understand the workings of culture and the community’s shared values. Their views about a community’s needs and potential solutions inform the core of collective community-based health improvement efforts, and help to assure community buy-in. Preparing youth for authentic involvement in community health improvement efforts is a strategy that serves both short and longer-term outcomes.

Young people have unique potential, as well as the energy, enthusiasm, optimism, and creativity to collaboratively seek solutions to complex and costly challenges. Being involved in organizing provides an important sense of validation and empowerment regarding their own lives and their community surroundings. Absent this solidarity, young people may misdirect blame and action for things that are not going well in their lives. For example, many hard-working students from poor communities are limited in their options for higher education and better jobs, not because of their own failing, but because systems and environments fail to create conditions favorable to advancement. Until young people understand how power and systems work, it is easy for self-blame and frustration to be untoward outcomes. Engaging them in community betterment serves several purposes, not only to improve present conditions for health, but also to prepare for a new generation of civic leadership and (potentially) careers in health. Youth organizing alumni are five times more likely than uninvolved youth to remain committed as young adults to civic involvement and three times more likely to be employed and/or going to college (Rogers and Terriquez, 2013).

Examples of Youth in Action

As a prelude to its April 10, 2014, workshop on the role of Community in Improving Population Health, the IOM Roundtable on Improving Population Health held a site visit to InnerCity Struggle (ICS) in Los Angeles. ICS employs an intergenerational community organizing approach to improve health and to address social inequities. By developing the leadership of parents and youth and engaging them in campaigns to improve learning and health conditions in schools, ICS has developed the civic capacity of community members, changed local school policies, and brought more educational and health resources into the neighborhood.

United Students is the youth organizing arm of ICS. United Students trains high school students that wish to address the problems of educational inequality, violence, and health disparities that impact their lives and limit their opportunities to obtain a higher education. A core group of about 45 high school students receive intensive leadership training. With guidance from young adult staff, this core group facilitates campus clubs at six local high schools that involve hundreds of students through lunchtime and after-school meetings focusing on leadership and advocacy for healthier conditions in schools and the community (Terriquez and Armenta, 2014).

Below, we share highlights, lessons learned, and some successes of several other California-based community health projects where young people are providing leadership and advocacy to improve community conditions for health and equity.

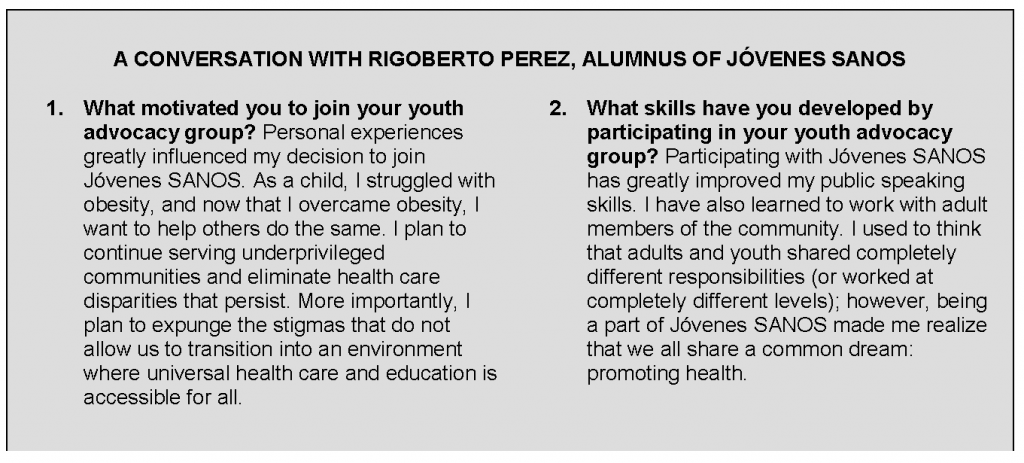

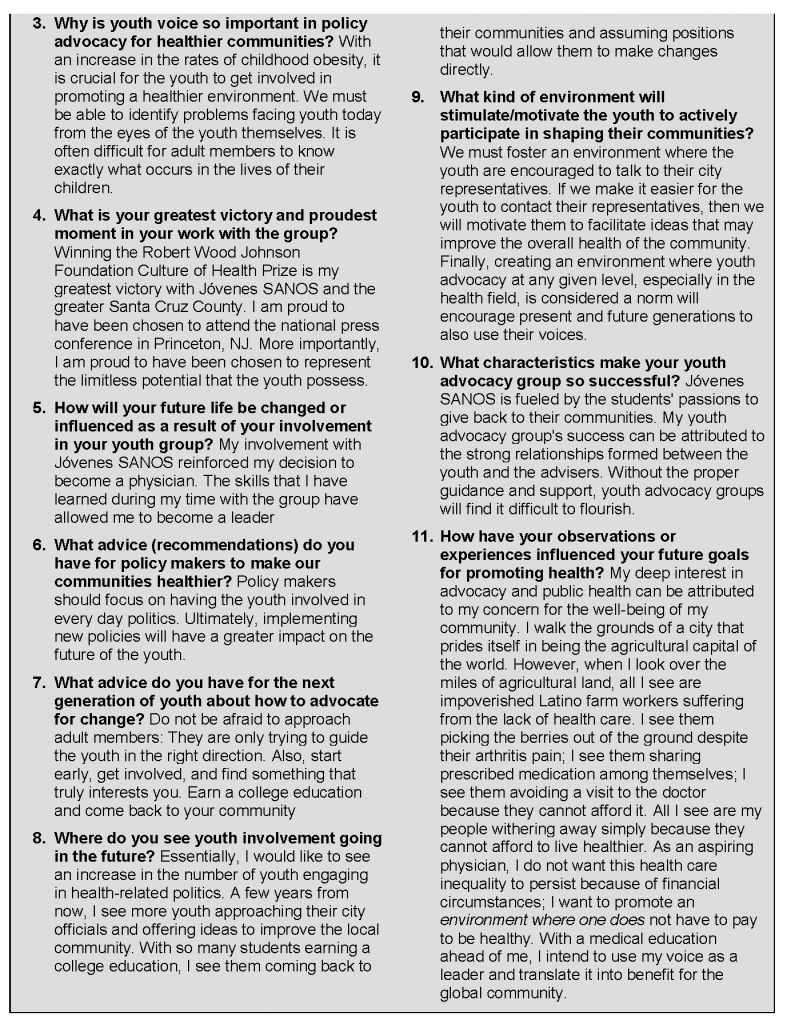

Jóvenes SANOS

Jóvenes SANOS is a high school youth advocacy project seeking to build an environment that embraces a culture of health by promoting access to affordable and healthy food options and opportunities for active living for the young people and families of Watsonville, California. Jóvenes SANOS youth work in different sectors of the community with many committed partners and endeavor to achieve their goals by proposing and implementing long-term environmental policy and system change. The group’s vision is to grow a world of healthy communities deeply rooted in equity and justice, and its mission is to achieve the vision by growing powerful, skilled young leaders. Markets in the community have been transformed into “Health Zones,” bike trails have been proposed and built, restaurants offer more healthy options than ever, free “healthy fun” events have happened and continue to happen. The greatest impact, however, is the lives of the youth: the youth who now have healthy options and can choose them. These youth are leaders and activists in their own communities and will carry these values and skills wherever they go.

United Way of Santa Cruz County and Jóvenes Sanos have identified several core principles and best practices. The principles are to

- educate and inspire, with practices that range from clearly defining the problem to explaining the system and understanding how to work within it;

- empower and engage, with practices that range from connecting problems to people’s lives to demonstrating flexibility;

- build capacity and leadership, with practices that include public speaking and opportunities for all (to develop skills and leadership abilities); and

- create and participate in community, with practices that include relationship building and encouraging mutual reliance.

Jóvenes SANOS also identified a set of tips for adults (e.g., community or public health leaders) working in partnership with young people. The tips include:

- Be reasonable and realistic in what is expected, and the compromises needed for progress.

- Be inclusive and supportive, but also fun and spontaneous.

- Become familiar with the youth, their neighborhoods, etc.

- Plan carefully.

- Put school first, while supporting other activities.

- Be authentic.

- Shared decision making whenever possible and transparency when not.

- Believe in youth.

Jóvenes SANOS Success Stories

The youth worked together over the past several years to advocate for municipal policies that support healthful nutrition choices. As a result, several policies were enacted or implemented. For example, a healthy restaurant options ordinance was enacted in October 2010. Initially, the ordinance applied to new restaurants, but preexisting restaurants may not participate. Jóvenes SANOS supports the promotion of the participating restaurants and encourages the community to choose these restaurants. All participating restaurants are acknowledged for their commitment with a decal that can be displayed in their place of business. In a related effort, the youth of Jóvenes SANOS worked with the Santa Cruz Metro Board to enact a healthy options vending/vendor policy, which included transitioning vending machines to a minimum of 50 percent healthy meal or snack options. Finally, the young people worked with corner market owners in Watsonville to “make over” the markets. The project included first conducting assessments, including visual audits, and entering into a memorandum of understanding with owners interested in participating. The project goal is to promote healthier eating by offering guidance and materials to support offering more health-promoting foods, informative signage and displays, and nutrition education events. Two markets underwent the makeover in 2013, and up to six additional stores may participate in 2014.

Physical activity is another area of focus for Jóvenes SANOS, and the youth’s activities in this area include implementing a fitness program for youth, designed in part to improve knowledge and awareness.

Youth Prompt Changes in School Discipline Policy

The “school-to-prison pipeline” refers to policies and practices that push students perceived as problems out of school and into the juvenile justice system as early as the fourth grade. Hispanic and African American boys are disproportionately affected, accounting for low school attendance, performance, and graduation rates and a cascade of lifelong challenges. Similarly, a “school to deportation pipeline” is identified in places where certain such students are reported to immigration authorities. Over the past few years, recognizing the inequities and the impact on health and on the community, youth in Fresno, Oakland, Long Beach, and Los Angeles organized to advocate for policy change. Virtual rallies were held that allowed youth to tell their stories. Many of these young people had no idea that other youth around California were also on the receiving end of high rates of harsh disciplinary measures. When they realized they were not the only ones, they felt empowered and emboldened in calling for change. Students appeared before local and state officials so they could tell their stories in their own words. As a result, school districts in those places and a growing number of others have moved to expand restorative justice policies and end reliance on “willful defiance” as grounds for suspension or expulsion. The governor signed four new laws aimed at keeping kids in school. The impact has been swift: In the 2012-13 school year, school suspensions statewide were down by more than 100,000, or 14.1 percent, and down by 28 percent compared to 2011-12. In that time, suspensions specifically for willful defiance dropped nearly 24 percent (Sacbee.com, 2014).

Youth Take Action to Increase Access to Health Services

Riverbank youth partnered with Golden Valley Health Centers to build awareness about the Medical Outreach Mobile Health Clinic (MOM). Through the Step-by-Step Community Youth Activist team, the youth developed a video to build awareness in their community about accessing medical services at the MOM, a temporary mobile clinic. A permanent school-based health center is being built on campus at Riverbank High School and will open this fall. Youth had initiated work to increase access to health care in 2006, when Riverbank High School students surveyed their peers and identified that access to appropriate and affordable health care services was a priority for their community. Since then, youth have been leading efforts in working with stakeholders and school administration to get a health center on their campus that provides access to the entire community.

Youth Power in Media

Youth voice is essential to youth organizing and advocacy. Health and justice-themed stories written and produced by youth fill the social media, and are driving public awareness and action in places like Coachella, Long Beach, Merced, Fresno, Richmond, South Kern, and Boyle Heights. Youth Radio, based in Oakland, is an award-winning media production company that trains diverse young people in digital media and technology. Partnering with industry professionals, students learn to produce marketable media for large audiences while bringing youth perspectives to issues of public concern. The Youth Radio mission is to launch young people on career and education pathways by engaging them in work-based learning opportunities, creative expression, professional development, and health and academic support services. Youth Radio stories reach thousands of listeners and are cited by numerous news outlets informing public opinion and policy decision making. Some recent health topics include Fresno youth on the need for health coverage for undocumented immigrants, a movement in Oakland working with young people who have been failed by institutions designed to support them, skateboarders in San Diego cleaning up their community, schools’ responses to e-cigarettes, depression among youth, and more.

Sons and Brothers

Health Happens Here with all our Sons and Brothers is developing youth leaders across the state who are advocating for public policies and system changes to ensure that young men of color have the chance to grow up healthy and get a good education and the opportunity to make positive contributions to their communities. The program organizes and trains participants to understand root causes of social and community issues, cultural consciousness, healthy masculinity, and movement building. The program is a model for President Barack Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative. Recently, the Presidential Task Force for My Brother’s Keeper released a 90-day progress report that cites critical statistics and personal accounts from young men of color and provides guidelines and specific recommendations for moving the initiative forward.

Aspiring to Health Careers

Pre-Health Dreamers (PHD) is a nationwide network of students, educators, and allies in support of undocumented immigrant pre-health career students, offering peer support and professional development, promoting community service, and leading advocacy for greater opportunities for health careers and health care for undocumented immigrants. PHD recognizes that motivated undocumented young people possess invaluable experience from having overcome significant obstacles and living in underserved communities. When allowed to put these experiences into practice through meaningful work, undocumented young people can help meet the rising demand for a diverse health care workforce. PHD strives to convince graduate and professional schools to adopt nondiscriminatory policies and attitudes toward students with complex immigration circumstances. The vision of Pre-Health Dreamers centers on the belief that immigration status should not exclude anybody from pursuing their dreams of higher education, careers, and contributions to their communities.

Youth as Changemakers

Change-making youth recognize that social adversity is a challenge not only to be overcome, but also to be removed so that others may succeed. Leveling the field, or advancing equity, is a core tenet of The California Endowment’s Building Healthy Communities. Fostering youth leadership to advance equity through personal development and constructive civic action is proving to be a key driver and promising practice for changing the conditions for improved population health to occur. Examples of multiple efforts that involve youth as leaders or participants include: mobilizing the Latino community for civic participation; dialogue with county supervisors about community priorities such as access to preventions services, support school performance, social connectedness, and graduation; decisions on school-related spending; and parent and student organizing to support the social and academic needs of African-American high-school youth (Ignant, 2014) (see Resources for more information).

Discussion

Shifting the emphasis in population health improvement from preventing widespread diseases to addressing the social and environmental factors that underpin health has opened the door to broad public involvement. With participation in community organizing and social media as informal indicators, young people are taking an increasingly prominent role in efforts to improve population health. Given sufficient training and guidance, the power of youth as agents for community change (leading to health improvement) is surfacing in school and civic decision making, media accounts, and project reports, but is less recognized in scientific literature. This trend indicating early personal investment in social good is a positive sign—one that portends a brighter future for population health, equity, and for civic engagement as well.

References

- Ginwright, S. and T. James. 2002. From assets to agents of change: Social justice, organizing, and youth development. New Directions For Youth Development 96: 27-46. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.25

- Christens, B. D., & B. Kirshner. 2011. Taking stock of youth organizing: An interdisciplinary perspective. In C. A. Flanagan & B. D. Christens (Eds.), Youth civic development: Work at the cutting edge. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 134, 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.309

- Ignant, C. 2014. Marginalized on Campus Black High School Students and Parents Organize. Richmond Pulse / New America Media, News Report. Available at: http://newamericamedia.org/2014/05http://newamericamedia.org/2014/05/marginalized-on-campusblack-high-school-students-and-parents-organize.php/marginalized-on-campus-black-high-schoolstudents-andparents-organize.php (accessed June 11, 2020).

- Rogers, J., and V. Terriquez. 2013. Learning to lead: The impact of youth organizing on the educational and civic trajectories of low-income youth. Los Angeles, CA: Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED574627 (accessed June 11, 2020).

- Sacbee.com. 2014. California sees sharp drop in school expulsions, suspensions. Capitol Alert, Sacramento Bee.

- Sullivan, L., D. Edwards, N. A. Johnson, and K. McGillicuddy. 2003. An emerging model for working with youth: Community development + youth development = youth organizing. New York, NY: Funders’ Collaborative on Youth Organizing.

- Terriquez, V. and G. Dominguez. 2014. Building healthy communities through youth leadership: Summary of key findings from the 2013-2014 Youth Program Participant Survey. USC Program for Environmental and Regional Equity. Available at: http://dornsife.usc.edu/pere/BHC-youth-leadership (accessed September 9, 2014).

- Terriquez, V., and R. Armenta. Forthcoming. Promoting Latino health through intergenerational community organizing: The case of InnerCity Struggle in East Los Angeles. USC Program for Environmental and Regional Equity.

Resources

For more information about efforts involving youth in several communities across California:

- http://californiacenter.org/youthvoices/riverbank_youth_build_awareness_about_accessing_medical_services/ (Riverbank [Central Valley] youth efforts)

- http://www.calendow.org/youth_action/sons-and-brothers-youth.aspx (Health Happens Here with all our Sons and Brothers)

- http://www.phdreamers.org/ (Pre-Health Dreamers)

- www.coachellaunincorporated.org (for information on Mi Familia Vota and other student action)

- www.southkernsol.org (Kern County)

- http://www.richmondpulse.org (work of Richmond youth coalition and other efforts)