Safe Summer Parks Programs Reduce Violence and Improve Health in Los Angeles County

In Los Angeles County, California, a promising new model for violence prevention and health promotion, rooted in cross-sector collaboration, has implications for how public health agencies serve communities. Safe Summer Parks programs were developed as violence prevention strategies, but they also have the potential to improve physical activity, social cohesion, and other outcomes that will, in turn, enhance health and well-being in underserved communities. More than any other factor, where people live determines their health (Senterfitt et al., 2013; University of Wisconsin, 2014). Social determinants of health, such as community safety, can be a critical barrier to health promotion that requires a place-based approach, characterized by collaboration both within public health and across sectors to more efficiently and effectively improve population health and well-being. By keeping parks open late during summer weekend evenings, jurisdictions are providing vulnerable communities with a safe space to gather, free recreation and educational programming, and access to needed health and social service resources. This relatively simple idea, a summer event, can produce important systemic changes and demonstrate how government and community organizations across sectors can work together to serve communities.

The Interrelationship Between Violence and Chronic Disease in Underserved Communities

Communities of low socioeconomic status are disproportionately affected by a range of health issues, including obesity, chronic disease, and violence (Shih et al., 2013; Prevention Institute, 2010). Public health practitioners identify communities most at risk and develop strategies to target resources to these health issues. Although we understand that such issues as those described above are interrelated, efforts to improve nutrition, increase physical activity, and reduce violence often follow separate “tracks,” i.e., these efforts are led by separate programs which have different funding streams. Violence in itself is a significant hurdle to health promotion that must be addressed before other strategies can be successful, particularly in high risk, underserved communities, which are often most affected by violence. Research demonstrates that violence is a contagion that has significant negative long-term impacts on health and well-being across the lifespan, including brain development, risk-taking behavior, post-traumatic stress disorder, and physiological stress that puts individuals at greater risk for chronic disease (IOM, 2012; Reingle et al., 2012).

Although homicide rates have steadily decreased nationwide since a peak in the early 1990s, underserved populations and communities remain at disproportionately high risk for injury and death resulting from violence (McDowall et al., 2009; CDC, 2013; U.S. DOJ, 2013). In Los Angeles County, youth ages 15-24 and Hispanic and African American males in particular are at increased risk for injury and death from homicides and assault injuries (LAC DPH, 2013). Violence and chronic disease, including obesity, are increasingly linked. People who have high exposure to neighborhood violence or who perceive their neighborhood to be unsafe are more likely to be physically inactive and overweight (Prevention Institute, 2010). According to a 2010 report from the Prevention Institute, violence and activity-related chronic diseases “are most pervasive in disenfranchised communities, where they occur more frequently and with greater severity, making them fundamental equality issues.” In Los Angeles County Department of Public Health’s (DPH’s) work with underserved communities to increase physical activity and healthy eating, local residents identify violence as a key issue. Perception of safety and high rates of crime reduce residents’ willingness to gather in public space, with consequent social isolation and decreased civic engagement (Prevention Institute, 2010; Roman et al., 2008). Social cohesion is a critical protective factor for building community resilience to reduce violence and promote health (Sampson, 1997; Losel et al., 2012).

Underserved communities have fewer resources than their wealthier counterparts to encourage physical activity and social gathering—backyards, green and public space, and opportunities or financial means to participate in health clubs or sports programs. Although park space is critically lacking in many communities throughout Los Angeles, parks often are the sole resource for recreation and engagement in vulnerable communities (Cohen et al., 2012; Loukaitou-Sideris et al., 2002). Yet existing parks are underutilized due to fear of violence and high levels of crime and gang involvement, which inhibit physical activity and active living efforts (The California Endowment, 2010; Broyles et al., 2011). For youth in particular, who are disproportionately affected by violence, availability of quality out-of-school-time programming is a critical protective factor (Fight Crime Invest in Kids, 2004). In Los Angeles County, quality out-of-school-time programming is scarce due to lost funding for summer school programs and limited free recreational opportunities. Parks are a tremendous resource to advance public health, and parks and recreation departments are natural partners for providing outreach to communities. Parks have great potential to serve as community centers for underserved communities and residents of all ages, providing a convenient and neutral space to access a range of health and social services, build community networks, and provide free and low-cost opportunities for recreation, education, and outreach in a safe space.

Safe Summer Parks Programs in Los Angeles County

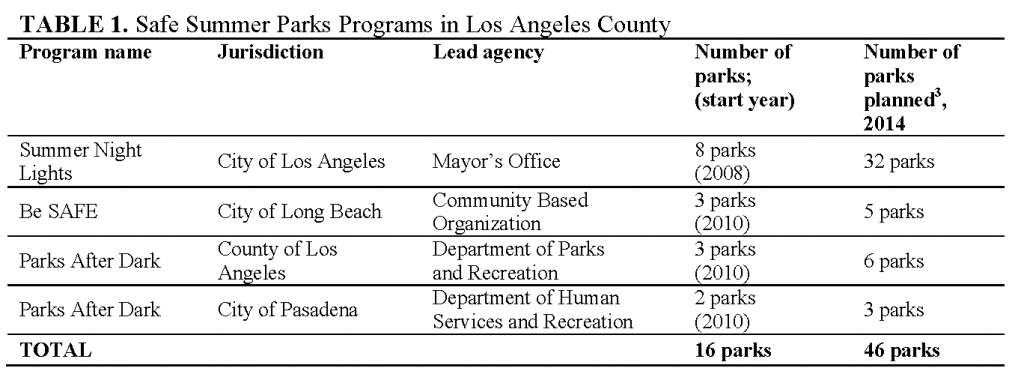

Through Los Angeles County’s various Safe Summer Parks programs, parks remain open during summer weekend evenings and provide a wide range of programs and services for youth and families in underserved communities. This strategy originated as part of local violence reduction initiatives and illustrates how a public health approach involving many agencies can reduce crime and may improve community health and well-being. Safe Summer Parks programs (Summer Night Lights [SNL]) began in the City of Los Angeles in 2008 as part of the mayor’s Gang Reduction and Youth Development (GRYD) initiative, a comprehensive violence prevention strategy that includes prevention, intervention, and suppression strategies targeted to select communities with high rates of gang violence (City of Los Angeles, 2007; Sulaiman, 2013). Other jurisdictions in the county soon followed suit, developing their own Safe Summer Parks programs (see Table 1).

Although the four Safe Summer Parks programs in Table 1 have some core common elements, in response to different local conditions and needs, they have different management structures, unique program elements, and trajectories. However, each program has demonstrated long-term reductions in crime and has become a promising practice for addressing other social and health indicators (Dunworth et al., 2011; Carey & Associates, 2011). Here we describe the county’s Parks After Dark (PAD) program to illustrate the potential to broaden the vision of Safe Summer Parks programs, incorporating public health promotion with violence prevention efforts and sharing the improvements in violence prevention, health, and well-being in these high-risk communities.

Parks After Dark: From Violence Prevention to Health Promotion

The six PAD communities are disproportionately impacted by both violence and obesity, and they have higher economic hardship than the rest of the county. PAD was specifically designed for summer evening hours, when crime rates are highest and youth have fewer social and recreational opportunities. Safety is a core element of PAD—sheriff’s deputies patrol the events and participate in activities along with community members. Local law enforcement also provides community safety education and self-defense classes. Their involvement sends a strong message that crime and violence are not tolerated and provides opportunities for youth, community members, and law enforcement to interact in a positive context.

PAD provides opportunities to participate in recreational activities, such as basketball, baseball, swimming, soccer, golf and tennis lessons, martial arts, dance classes, walking clubs, Zumba®, bike rides, and to access community pools and gym facilities. PAD also offers entertainment programming, including movies, talent shows, and concerts, and incorporates a variety of educational programs addressing topics such as healthy cooking, literacy, parenting, arts and crafts, the juvenile justice system, and computer skills. Moreover, in communities that often lack such access, PAD connects people with health and wellness, economic, legal, and social services through resource fairs and other events. These resource fairs engage a wide range of sectors, including library, law enforcement, public defense, public works, public health, probation, arts commission, fire department, radio stations, community- and faith-based organizations, local businesses, elected officials, and professional sports, to provide community outreach.

PAD is coordinated by the Department of Parks and Recreation (Parks) in partnership with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, Chief Executive Office, Department of Public Health (DPH), and many other county and community partners. PAD originated as the prevention strategy of the Los Angeles County Gang Violence Reduction Initiative that targeted four unincorporated demonstration site communities with high rates of gang violence (LAC CEO, 2009).

PAD’s success is dependent on cross-sector collaboration to improve the health and safety of residents in vulnerable, gang-impacted communities; however, it is the Parks and Recreation department that has taken the lead. PAD partner organizations are engaged in the planning process prior to each summer, as well as debrief meetings after PAD ends.

DPH has been a partner for the county PAD program since the planning phase of the Gang Violence Reduction Initiative, assisting with program development and evaluation and providing health outreach. Its role in PAD has evolved over the years. The Injury & Violence Prevention Program (IVPP) within the Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention was a partner in the development of the Gang Violence Reduction Initiative, participating in community planning meetings, refining strategies and recommendations such as PAD, developing conceptual models, collecting data, and assisting with reports and assessment activities. IVPP provided analysis of PAD participant satisfaction surveys since it began in 2010. Public health nurses working in South Los Angeles developed innovative and successful walking clubs that incorporated health education during PAD beginning in 2010. Several DPH programs participate in PAD resource fairs each summer, providing information and services that address women’s health, environmental health, nutrition, childhood lead poisoning prevention, and HIV/STD prevention.

From 2012 to 2014, PAD received funding through DPH’s Community Transformation Grant, awarded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which helped build capacity to sustain the program, expand it to three additional county parks, and evaluate it as an innovative program. IVPP’s role expanded to include efforts to build the evidence base for PAD, engaging partners both within DPH and with other sectors, promoting the success of the PAD program via media events and professional conferences, conducting a rapid Health Impact Assessment (HIA), and working closely with Parks to develop a strategic plan to sustain and expand PAD. DPH has largely played a supportive role for the county’s PAD program, and while its role has evolved over the years and PAD is being adopted as a public health strategy, there remains a lot of potential for targeted health outreach in the PAD communities.

Impact of Parks After Dark

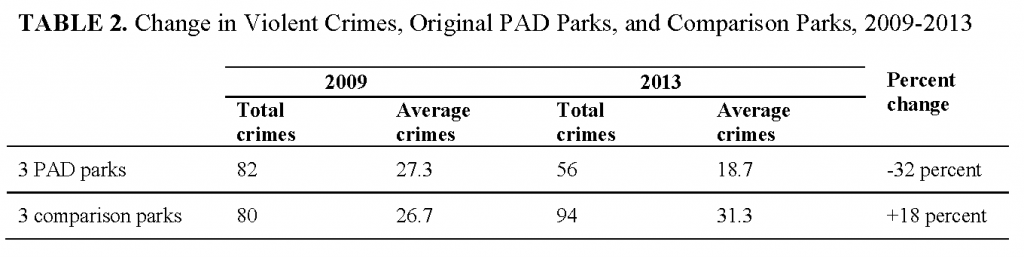

The impact of PAD on its communities to date has been impressive. Since it began in summer 2010, there have been more than 187,000 total visits to the six parks. Attendance has grown each summer as community awareness grows and residents look forward to the summer programs. Participant satisfaction surveys indicate that community members of all ages participate in PAD programs: In 2013, 39 percent of the participants were under age 18, 13 percent were ages 18-25, and 45 percent were adults over age 25. Serious and violent crimes in the communities surrounding the original three parks declined 32 percent during the summer months between 2009 (the summer before the program started) and 2013, compared to an 18 percent increase in serious and violent crime during this period in similar nearby communities with parks that did not implement PAD. ( Notes on crime analyses: Serious and violent crimes are Part 1 crimes, which include homicide, rape, aggravated assault, robbery, burglary, larceny theft, grand theft auto, and arson. The surrounding community was defined as the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department reporting district surrounding the park; these are roughly the size of, and tend to align with, the immediate census tract. PAD parks are located in unincorporated communities that border other cities with separate law enforcement agencies; data from these agencies were unavailable at time of analysis to calculate crimes within a ½ mile radius, which would provide a more inclusive understanding of the programs impact on crime. Average violent crimes during a 9-week period during the summer were compared between 2009 and 2013. Comparison parks are demographically similar unincorporated county parks and located near the intervention parks.) Ninety-seven percent of respondents to a 2013 survey felt safe during PAD. Most participants (86 percent) said they felt safe from crime in their neighborhoods. However, of those who did not feel safe, 88 percent reported that they felt safe during PAD-sponsored events.

PAD also may reduce obesity rates by providing opportunities for safe physical activity. According to Parks records, there were more than 16,000 participants in physical activity programming during PAD in 2013. Participant satisfaction survey results indicated that 70 percent of adults and young adults reported receiving less than the recommended level of weekly physical activity (thirty minutes per day, five or more days per week). However, 75 percent of those respondents participated in physical activities during PAD. Physical activities, including walking clubs that were developed by public health nurses, were among the most well-attended and popular for PAD participants. The walking clubs actively engaged local residents in physical activity and incorporated health education tailored to community needs, including nutrition, physical activity, and diabetes and heart disease prevention. Walking club participants become community champions, building local leadership as well as health literacy. Public health nurses also developed a toolkit for other groups to use to start their own walking clubs. Although PAD provides more opportunities for physical activity, more research is needed to determine the impact on obesity and related health outcomes.

Participant satisfaction shows the positive impact PAD has had on the community. Satisfaction has been near 100 percent each summer, and participants indicate a strong need and desire for the program to continue to improve safety, provide much-needed opportunities for recreation and outreach, and bring the community together. PAD’s impact on improving social cohesion in its communities is also evident in feedback provided by the program’s key partners at DPH, the Sheriff’s Department, and Parks, as well as in many anecdotes (the qualitative information that gives meaning to the quantitative findings). At a park in Duarte, neighbors started a spontaneous potluck dinner during PAD. Sheriff’s deputies organize basketball and kickball tournaments with local youth and community members each summer. Park staff reached out to local homeless families to participate in the activities and get involved with the community. A community organization organized a bike ride between parks in rival communities, bridging the divide between Hispanic and African American communities. PAD also strengthened relationships between community members and law enforcement, as well as other governmental organizations providing services during the events.

Community engagement has always been a critical piece of PAD. Communities identified the need for summer park programming during the Gang Violence Reduction Initiative planning process. Parks engages community members, leaders, and organizations in planning meetings each spring to determine programming needed for the summer, and reconvenes community members in the fall to discuss lessons learned. Parks engages youth and adult volunteers in program implementation. In 2014, PAD incorporated Youth Councils, building on existing teen clubs at the parks, to identify a health issue to address in their community. Parks and DPH are collaborating to engage youth in community-based participatory research activities in the coming year and will work with youth to develop and implement a project. Youth are exploring ideas such as developing physical activity programs, reducing graffiti, bridging the color lines from park to park, improving traffic safety, and developing community gardens. The goal of this effort is to get youth involved in the community, build leadership, and actively engage the community in positive change. The Youth Councils also have the potential to further build relationships between DPH and Parks and build infrastructure for youth health advocacy in the county.

PAD originated in and depends on cross-sector collaboration. These summer events have cemented relationships among DPH, Parks, and the Sheriff’s Department. Such cross-sector collaboration improves the efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery, as well as enhancing community resilience, which is vital for a range of public health priorities, including violence prevention and emergency preparedness.

The extent of Safe Summer Parks programs like PAD remains modest relative to the needs of Los Angeles County, which is more populous than 42 states in the nation. Parks and DPH continue to work together to develop a strategic plan to sustain, enhance, and expand PAD to additional unincorporated communities, including exploring how parks may be used to influence a wider range of health and well-being objectives in vulnerable communities. With Community Transformation Grant funding ending abruptly two years earlier than initially planned, due to federal budget cuts, the future of PAD is uncertain. However, five years of cross-sector collaboration and its positive impact on the community have given PAD momentum. DPH and Parks are engaging partners in a formal Strategic Planning Committee which will develop and implement a long-term sustainability plan for PAD. DPH is conducting a rapid HIA to evaluate the potential health impacts of expanding PAD to additional unincorporated county parks, as well as assessing potential reductions in criminal justice and health care costs, and cost savings for families who do not otherwise have the resources to afford these programs. The HIA may help PAD, as well as other Safe Summer Parks programs throughout the county and other jurisdictions considering such programs. DPH and Parks are exploring a regional approach with the other Safe Summer Parks programs to improve collaboration across jurisdictions, and determine how they could be expanded to underserved communities in the other 85 cities in Los Angeles County. PAD is a remnant of the county’s gang initiative, which was targeted to unincorporated communities and ended in early 2013. While DPH and Parks explore how PAD enhances health and social service outreach, it also may provide a foundation for future violence prevention strategies in the county.

Conclusion

PAD exemplifies a new model of violence prevention for Los Angeles County that is emerging in communities across California and other parts of the country. Safe Summer Parks programs may transform underserved communities not only by improving safety but by improving access to free recreational activities, physical activity programming, youth engagement, and health and social service outreach, and by strengthening communities. As a violence prevention strategy, formal evaluation for these programs is focused on crime reduction. Although PAD may improve other dimensions of community health, additional resources will be required to assess physical activity and obesity in particular. Additionally, the effect of Safe Summer Parks programs on improved social cohesion, which may be driving improved safety and other positive community impacts, warrants further study.

Professionals in public health and other sectors serving high-need communities consistently need to find ways to do more with less, include community input in initiatives, and demonstrate cross-sector collaboration. Safe Summer Parks programs provide a model for how local governments and community organizations can effectively realign and optimize resources. Funders frequently require applicants to incorporate cross-sector collaboration and leverage other local initiatives; however, funding opportunities are often themselves siloed. A continuing challenge is the paucity of funding for violence prevention; what is available still largely focuses on suppression activities. In the public health setting, violence prevention is too often a secondary consideration for funding. Safe Summer Parks programs may be a promising approach to address these gaps by specifically incorporating violence prevention in chronic disease and health promotion funding streams. The programs are proving to be a successful place-based approach that utilizes parks as community centers, coordinates health outreach, and leverages the work of parks, law enforcement, and social services to more holistically improve the social determinants of health.

References

- Broyles S. T., A. J. Mowen, K. P. Theall, J. Gustat, and A. L. Rung. 2011. Integrating Social Capital Into a Park-Use and Active-Living Framework. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 40(5):522-529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.028

- The California Endowment. Reclaiming public spaces: Taking action to make neighborhoods safe and parks accessible. December 2010.

- Carey & Associates and Rethinking Greater Long Beach. 2011. Long Beach Building Healthy Communities Collaborative: 2010 Summer Night Lights in Long Beach: A case study.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Homicide rates among persons aged 10-24 years, United States, 1981-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62(27). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6227a1.htm (accessed May 26, 2020).

- Cohen D., B. Han, K. P. Derose, S. Williamson, T. Marsh, J. Rudick, and T. L. McKenzie. 2012. Neighborhood Poverty, Park Use, and Park-Based Physical Activity in a Southern California City. Social Science and Medicine 75(12City of Los Angeles Gang Reduction Strategy. 2007. Available at: www.lacounty.info/bos/sop/supdocs/32068.pdf. (accessed April 1, 2014).

- Dunworth T., D. Hayeslip, and M. Denver. 2011. Y2 Final Report: Evaluation of the Los Angeles Gang Reduction and Youth Development Program. Research Report. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/27581/412409-Y-Final-Report-Evaluation-of-the-Los-Angeles-Gang-Reduction-and-Youth-Development.PDF (accessed May 26, 2020).

- Fight Crime Invest in Kids California. 2004. California’s next after-school challenge: Keeping high school teens off the street and on the right track. Washington, DC. Available at: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/35495923/californias-next-after-school-challenge-fight-crime-invest-in-kids (accessed May 26, 2020).

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2013. Contagion of Violence: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13489

- Los Angeles County Chief Executive Office. 2009. Countywide gangs and violence reduction strategy. Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors Correspondence. Available at: http://www.lacounty.gov/wps/portal/bc (accessed April 1, 2014).

- Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Injury & Violence Prevention Program. 2013. Number and rate per 100,000 of homicides among LA County residents by year, 2006-2010 [online data table]. Available at: www.ph.lacounty.gov/ivpp (accessed April 1, 2014).

- Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Injury & Violence Prevention Program (Jan 2013). Number and rate per 100,000 of assault hospitalizations among LA County residents by year, 2006-2010 [online data table]. Available at: www.ph.lacounty.gov/ivpp (accessed April 1, 2014).

- Lösel, F. and D. P. Farrington. 2012. Direct protective and buffering protective factors in the development of youth violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43(2), S8-S23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.029

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. and O. Stieglitz. 2002. Children in Los Angeles parks: A study of equity, quality, and children’s satisfaction with neighborhood parks. Town Planning Review 74(4): 467-488. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40112531 (accessed May 26, 2020).

- McDowall, D. and C. Loftin. 2009. Do U.S. city crime rates follow a national trend? The influence of nationwide conditions on local crime patterns. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 25:307-324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-009-9071-0

- Prevention Institute. 2010. Addressing the intersection: Preventing violence and promoting healthy eating and active living. Oakland, CA: Author. Available at: https://www.preventioninstitute.org/publications/addressing-the-intersection-preventing-violence-and-promoting-healthy-eating-and-active-living (accessed May 26, 2020).

- Reingle J. M., W. G. Jennings, A. R. Piquero, and M. M. Maldonado-Molina. 2013. Is Violence Bad for Your Health? An Assessment of Chronic Disease Outcomes in a Nationally Representative Sample. Justice Quarterly. ePub. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2012.689315

- Roman C. G. and A. Cahlfin. 2008. Fear of Walking Outdoors, A Multilevel Ecologic Analysis of Crime and disorder. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 34(4):306-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.017

- Sampson, R. J., S. W. Raudenbush, and F. Earls. 1997. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277(5328):918-924. Available at: http://illinois-online.org/krassa/ps410/Readings/Sampson%20Miltilevel%20Study%20of%20Collective%20Efficacy.pdf (accessed May 26, 2020).

- Shih M., K. A. Dumke, M. I. Goran, and P. A. Simon. 2013. The association between community-level economic hardship and childhood obesity prevalence in Los Angeles. Pediatric Obesity 8(6):411-417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00123.x

- Senterfitt J. W., A. Long, M. Shih, and S. M. Teutsch. 2013. How Social and Economic Factors Affect Health. Social Determinants of Health, Issue no. 1. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. Available at: http://la.streetsblog.org/2013/06/28/transforming-summer-night-lights-to-yearround-lights-could-work-wonders-for-communities-where-access-to-public-space-is-limited/ (accessed April 1, 2014).

- University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. 2014. County health rankings key findings 2014. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. 2013. Homicide in the U.S. known to law enforcement, 2011. Patterns and trends. Available at: https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/2014%20County%20Health%20Rankings%20Key%20Findings.pdf (accessed May 26, 2020).