Return on Information: A Standard Model for Assessing Institutional Return on Electronic Health Records

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines a learning health system as a system that has the capacity to both apply and generate reliable scientific evidence in the delivery of care (IOM, 2007). Although it may seem obvious that both the demands for higher reliability and higher-value health care require robust electronic health records (EHRs), information exchange, and deep analytic capabilities, it remains difficult to measure the return on investment (ROI) in information systems. The lack of a standard model for ascribing the costs of implementing or the benefits of using EHRs and related technology makes comparisons across different institutional experiences, different implementation approaches, and different technologies difficult. Moreover, the absence of a format for a standard business case for information investment may add to the hesitation for investment in information systems and thwart progress in creating the reliable digital foundation needed for a continuously learning health system.

A standard model for ascribing costs and benefits would need to specify what constitutes the entity investing (i.e., what are defined as the organization’s boundaries), what constitutes the information system, what constitutes infrastructure that should or should not be included in a model, and what differentiates the information system from related technologies. Similarly, a standard model would specify not only how costs or benefits might be attributed to use of the information system, but also how these costs and benefits should be handled in a financial model. While a number of thoughtful analyses of costs and benefits of electronic health records have been published, each one has used different and, consequently, incomparable methods (Adler-Milstein et al., 2013; DesRoches et al., 2013; Fleming et al., 2011; Hillestad et al., 2005; Kaushal et al., 2006; Walker et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2003). Thus, the goal of this paper and the associated model is to provide a clear framework and propose a standard model for evaluating institutional investment in EHRs and related technologies to enable inter-organizational comparisons, help identify best-in-class implementation approaches, and prioritize process redesign endeavors. Given the institutional focus of this model, it is likely to be primarily useful to hospitals and health systems, rather than unaffiliated ambulatory care offices.

The authors are individual participants from the Digital Learning Collaborative of the IOM Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care. The collaborative seeks to accelerate progress toward the digital infrastructure necessary to achieve the roundtable’s goal of continuous learning, improvement, and innovation in health and health care. We have also collaborated with health system leaders and colleagues from health care finance, economics, and information to identify proposed elements for a model to quantify and analyze the ROI from implementing electronic health technology. The collaborative is inclusive—without walls—and its participants include clinicians, patients, researchers, software developers, and health care financial experts.

Why a Common Value Realization Framework is Essential

Robust health information technology (IT) infrastructure and health information exchange (HIE) are essential to achieve the vision of a learning health system. Achieving such a vision is a multifaceted challenge that calls for comprehensive implementation and effective use of interoperable health IT by a continually engaged research and data analytics infrastructure that generates actionable evidence to inform future care. Such a system, coupled with the business and care delivery process re-engineering that it enables, is expected to return value to all stakeholders, but the cost of implementing the necessary changes, such as interoperable EHRs and transforming practices, is carried primarily by health care providers.

Providers (individual and organizational) must weigh whether and when to invest their limited resources in health IT rather than other infrastructure and process improvements that would also return value to their patient-care missions. Currently, it is difficult to demonstrate the provider’s business case for health IT investment because a commonly accepted framework is lacking for identifying and quantifying costs and benefits that is suitable for use across provider types and reimbursement models. A generally accepted, standardized but flexible analytic framework for calculating the provider’s ROI from interoperable health IT and HIE can support strategic investment decisions, such as timing and product selection. With widespread use, a generally accepted business case framework will enable benchmarking across similarly situated providers to identify best practices in health IT selection, implementation, and use, and thus dispel concerns raised by negative anecdotes.

Although there have been promising reports on positive return on provider organizations’ investments at scale, the methodologies used have not been generalizable across provider organizations, given differences in organizational structure and payer reimbursement policies (Wang et al., 2003). Assessments from individual provider perspectives have also not been conclusive. Without a generally applicable standard for quantifying providers’ value realization from their investments in health IT, variation in results of applying different models and methods contribute to uncertainty and inertia in providers’ consideration of the transition to interoperable health IT. In order to have rational discussions about value, and compare effectiveness of EHR integration, general standards are needed.

A Rapidly Changing Business and Policy Environment

The fact remains that health care is a reluctant late adopter when it comes to IT. Although health care is information- and technology-intensive, it has lagged behind other industries in the widespread deployment and use of information technology in ways analogous to the information technology-fueled increases seen recently in similarly complex industries. In fact, health care leads only mining and construction in realization of productivity growth largely attributable to the widespread implementation of information technology (Cutler, 2009).

However, the health IT environment is changing rapidly. Among the most significant policies shaping the current context of the health care information systems market is the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act passed as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. HITECH authorized almost $30 billion in federal financial incentives for eligible hospitals (Acute-care inpatient (§1886[d]) hospitals are eligible for incentives under §1886 of the Social Security Act, and Critical Access Hospitals are eligible for financial incentives authorized at §1814 of the Social Security Act, as modified by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). Titles XII of Division A and IV of Division B together are referenced as the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act.) and professionals adopting and demonstrating “meaningful use” of certified EHR technology. This effort has driven a significant increase in health IT adoption, with hospital adoption of at least a basic EHR system increasing from around 10 percent in 2008 to 44 percent in 2012 (DesRoches et al., 2013). In addition, the regulatory EHR certification criteria and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ EHR Incentive Programs’ meaningful use requirements for incentive payments have driven rapid increases in the availability and use of interoperable health IT across the country.

Enactment of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) has accelerated innovation in health care delivery and payment systems that will make standards-based, interoperable information systems increasingly necessary for providers to thrive in coming years. Alternative payment regimes such as bundled payments, and shared risk models, such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), require more intensive collection, use, and sharing of clinical information and reporting of high-quality data to payers and purchasers. In addition, accompanying pressures to increase efficiency and provide higher-value care by controlling costs while maintaining quality, require a sophisticated understanding of clinical and administrative operations. These current and growing requirements are shaping the investment in and deployment of information systems by large and small delivery organizations vying to remain competitive in the changing health care marketplace.

Considering the Business Case

Despite the context of increasingly compelling business and policy environments, organizations attempting to calculate a business case and make investment decisions about health information systems continue to face many challenges, both logistical and conceptual. Logistically, calculation of ROI requires a thorough understanding of the baseline against which costs and benefits can be measured, an understanding that can vary based on the existing infrastructure of an organization. Conceptually, all organizations face challenges determining the scope and attribution of returns to the health information systems.

For example, benefits of robust information system implementation might include savings to an organization from the reduction or more effective deployment of full-time equivalents (FTEs) associated with more efficient business practices, decreased morbidity and mortality due to more consistently delivered, high-quality care, avoided complications from improved preventive care, and enhanced patient experience and outcomes through the opportunities afforded by EHRs and patient portals for engagement. In the first instance, the benefit is clearly realized within the same organization, while in the second the benefit might be considered to accrue primarily to society. For this reason, business case calculations can vary greatly depending on the scope to which the model calculation is constrained. It is not uncommon for costs and benefits to accrue differently to different stakeholders across the broad scope of the health care system.

Health care information systems are large and complex, impacting many parts of a health care delivery organization. Their performance affects and is affected by factors beyond the information system itself. Realizing full value of the system typically depends not only on successful deployment of the system but also on adaptation of other organizational processes and workflows. These factors pose challenges to the development of a business case by complicating both the attribution of costs and benefits, and the ability to draw causal relationships between them. Furthermore, these complex relationships can make anticipation of costs and benefits difficult and unintended consequences challenging to predict.

Another variable to be considered is the extent of function an EHR provides. To some degree, this is specific to the particular EHR and the robustness of its features. However, functionality is also enhanced or constrained by the quality of implementation, including user training and acceptance, as well as the universe of technology with which it is used. For example, an EHR might be able to receive input from medical devices (e.g., that record blood pressure), thus reducing labor used for transcription and latency in acting on changes in patient status. However, if the provider setting does not have interoperable devices, the potential benefit cannot be realized. Importantly, the deployment of EHR elements is typically done in a modular, stepwise manner across an institution in order to best manage the concomitant cultural and educational issues. Because realization of certain benefits will be dependent on the stage of implementation and interconnection across these modules, the ROI assessment must address and accommodate the circumstances at the individual stages, as well as those anticipated when fully operational.

The dependence of the return on interoperability can also extend beyond the walls of a single institution. Network effects that enable benefits achievable only if other members of the network have comparable technology, ability, and processes also pose a major challenge to understanding the boundaries to return calculations. A standard business case would specify the parameters for what is included, allowing comparability in calculations of cost and benefit across EHRs and provider institutions.

Examples of Approaches to Determine Return on Information

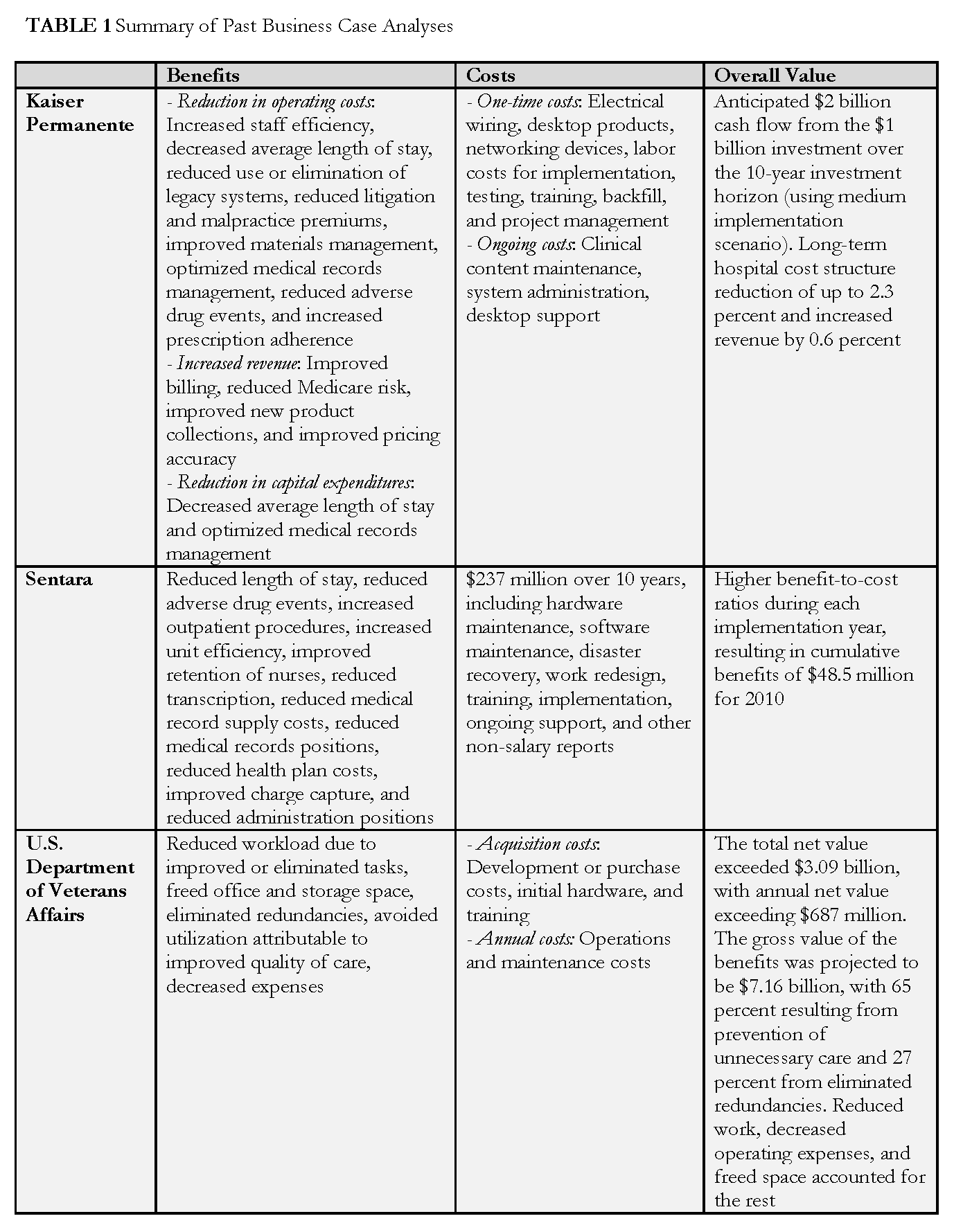

There have been several notable efforts to produce analytical models that predict potential return on investment from electronic health records (Hillestad et al., 2005; Walker et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2003); and some health care organizations have shared their health IT costs and documented benefits (Adler-Milstein et al., 2013; Fleming et al., 2011; Kaushal et al., 2006). Several of these examples were reviewed in the development of the model and are summarized below. In addition, more detail is provided in Table 1, demonstrating the variety of assumptions that are unique to each report and limit comparability, reinforcing the need for a standard model.

Among the examples reviewed were efforts from private industry, including Kaiser Permanente, which published a strategic business case analysis (Garrido et al., 2004) for its hospital information systems in 2004, and Sentara Healthcare, which measured the ROI for its information system and disseminated the results in 2011 (Konschak, 2011). These analyses differed in the costs and benefits evaluated, and in the case of the Kaiser study also assessed implementation and benefit realization lags, while the Sentara study included the redesign of 18 major processes. Also reviewed was a study from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system, which conducted an assessment of its health IT system in 2010 (Byrne et al., 2010). This study benchmarked VA adoption, cost, and impact against private sectors; modeled the financial value of VA’s health IT investment; and included only benefits for which there was strong evidence of their relation to EHR implementation. Also included was a recent study conducted across diverse practice settings, which showed how practice type differences and EHR uses can have implications for ROI (Adler-Milstein et al., 2013). The authors found that primary care and larger practices have higher ROIs, the reduction of paper medical record costs is the most common financial change, and practices that actively use EHRs to increase revenues have more positive ROIs. Finally, a literature review conducted in 2010 (Buntin et al., 2011) that assessed published outcomes from deployment of various forms of health IT was also reviewed. The literature review found that 92 percent of studies were either positive or mixed-positive, with 62 percent fully positive. Most negative findings were associated with workflow implications of health IT implementation, while strong leadership and staff “buy-in” were found to be critical to successfully manage and benefit from health IT.

Although the analyses summarized above are helpful, the variability in their methods and the costs and benefits they consider make it difficult to compare across cases or to draw overarching conclusions about the value of EHR systems.

Building the Model

To better understand and calculate the costs and benefits of investing in EHR systems, stemming from common interests as participants of the IOM’s Digital Learning Collaborative and members of the Healthcare Financial Management Association, we are proposing herein a standard model of evaluation. This tool is meant to be used as a guide by health system management teams—including CEOs, CFOs, COOs, CIOs, and clinicians, among others to help determine the financial impact of implementing and optimizing EHRs and related technologies. The key elements of the tool are presented as a catalog of categorized benefits, expenses, and potential revenue impacts and the accounts where these may be captured.

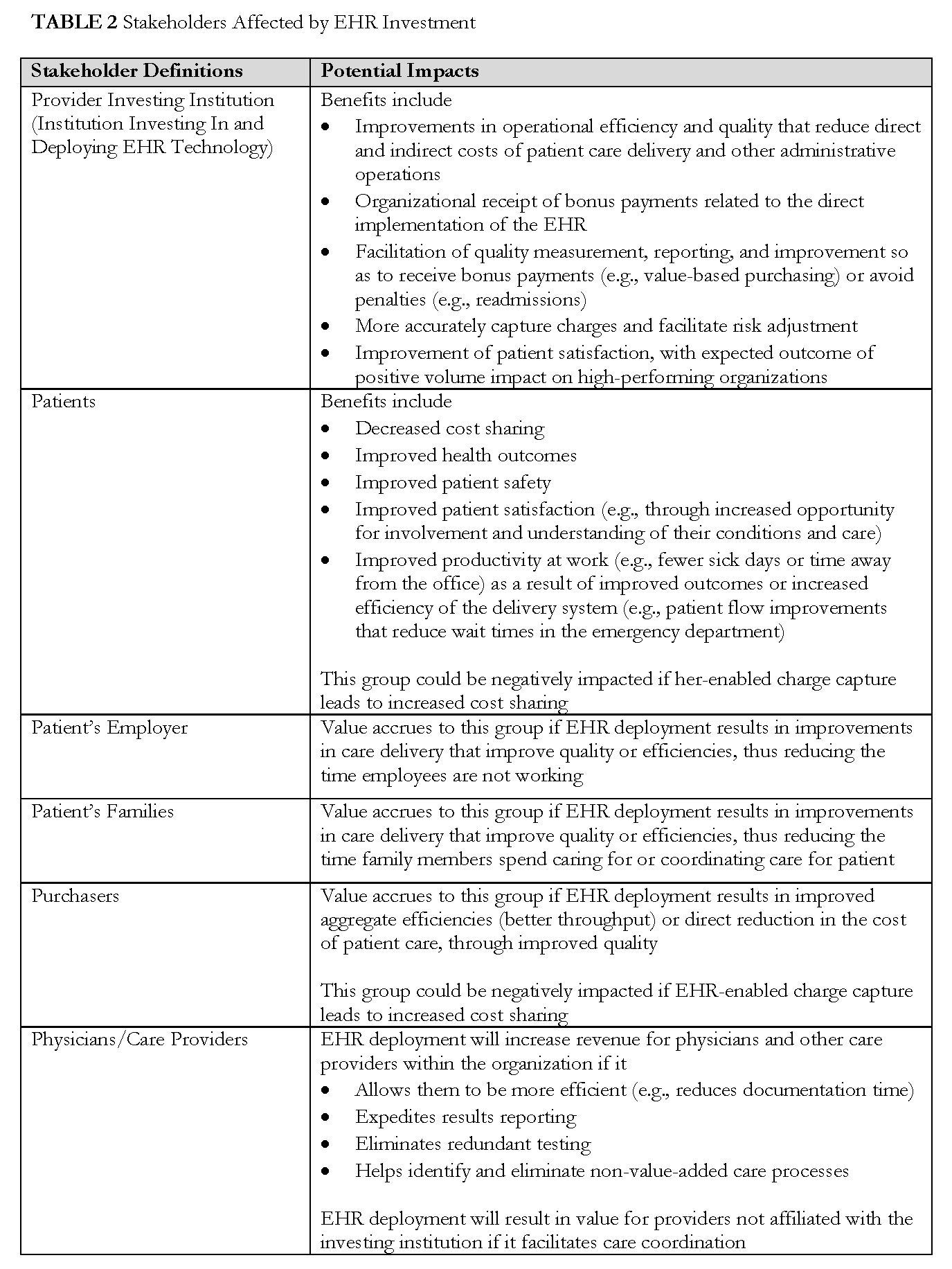

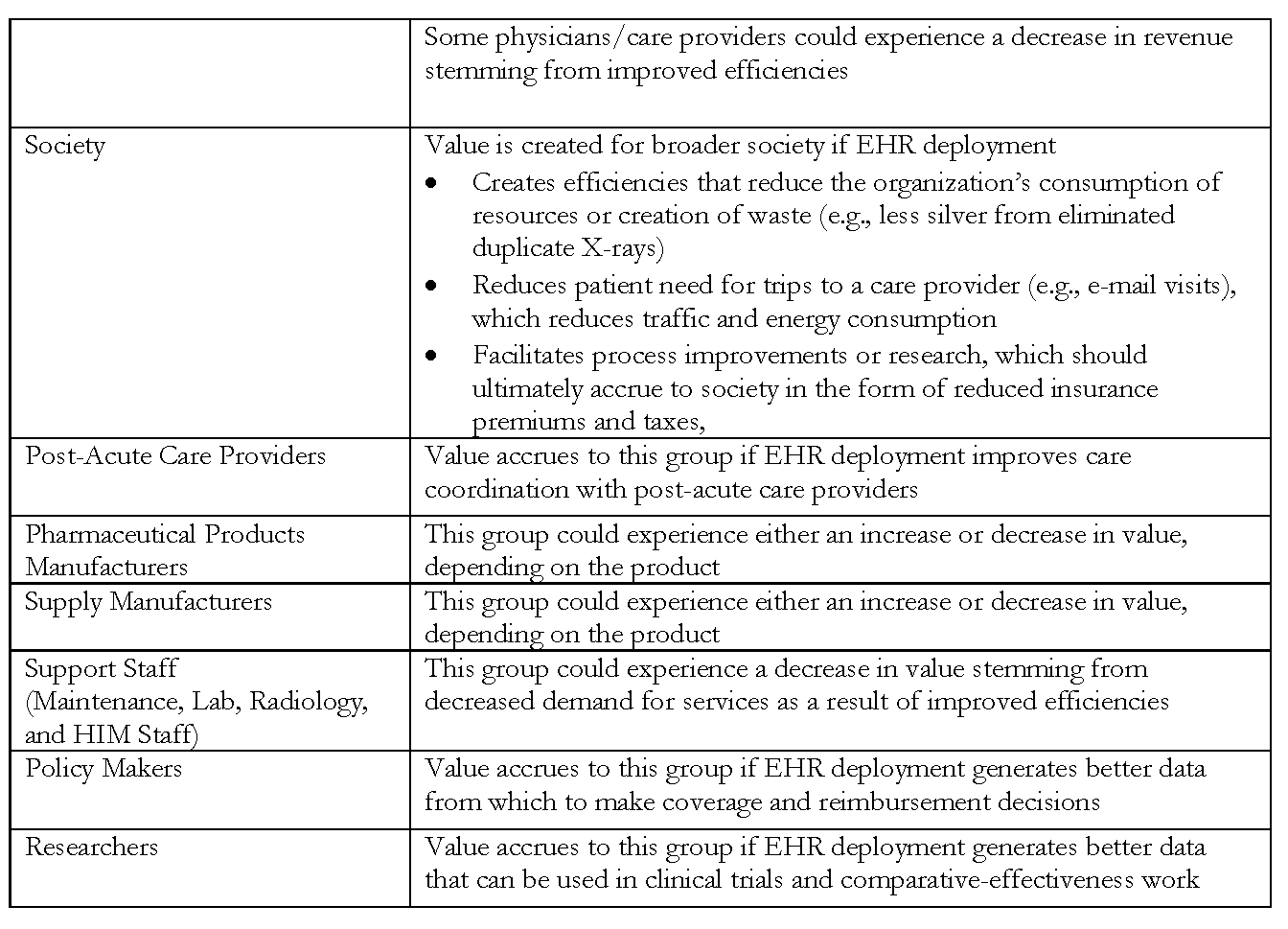

The fact that many stakeholders are impacted by organizational decisions to invest in EHR technology was considered in building this model. However, for the purposes of this initial phase, the focus of the model is the individual organization considering investment. To acknowledge the reality of broad impact, we identify other stakeholders affected by EHR investment throughout the model, and a full description of stakeholder definitions and the potential impacts can be found in Appendix 2. Future efforts may build on the model, to consider a broader range or different subset of impacted stakeholders.

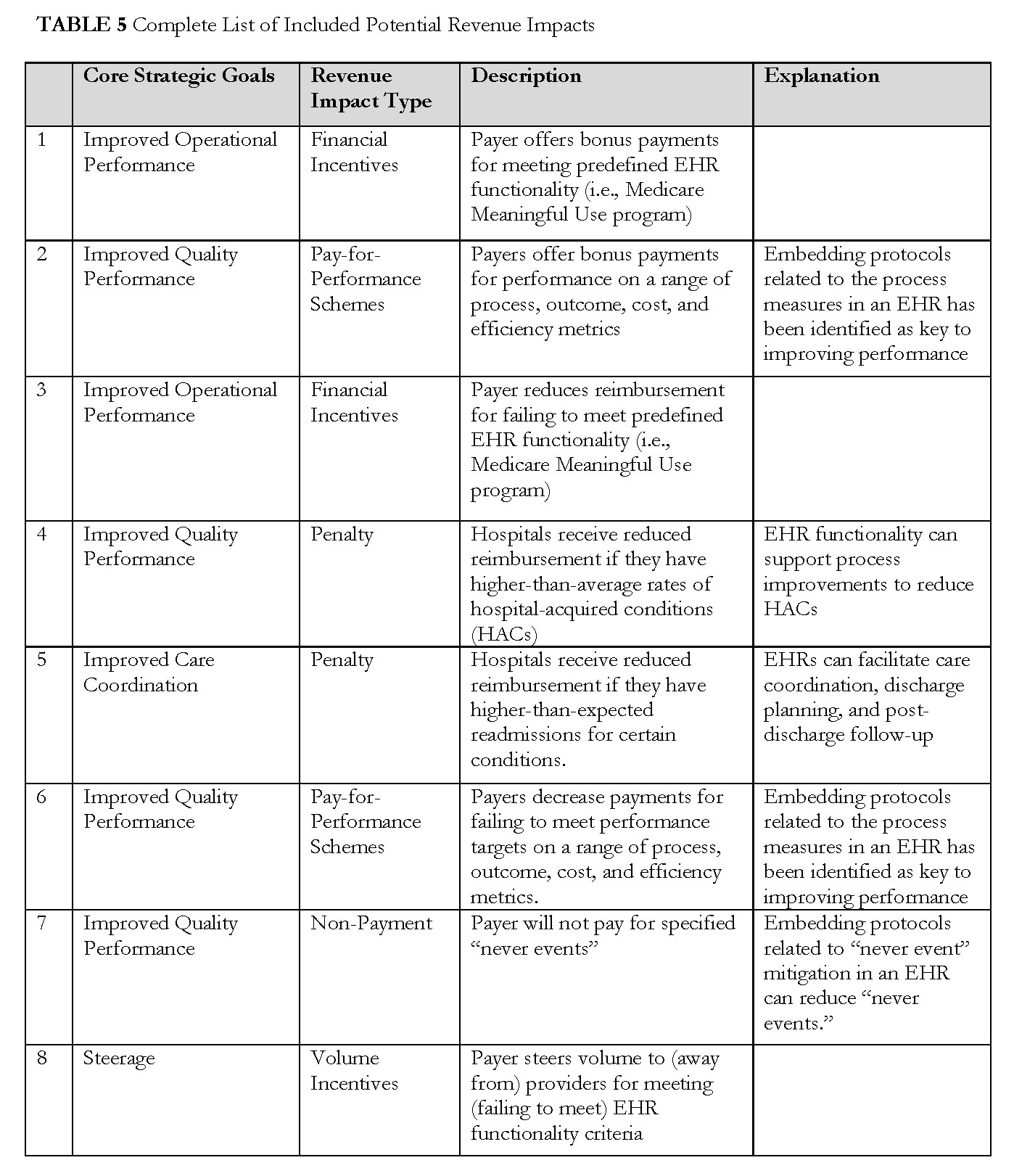

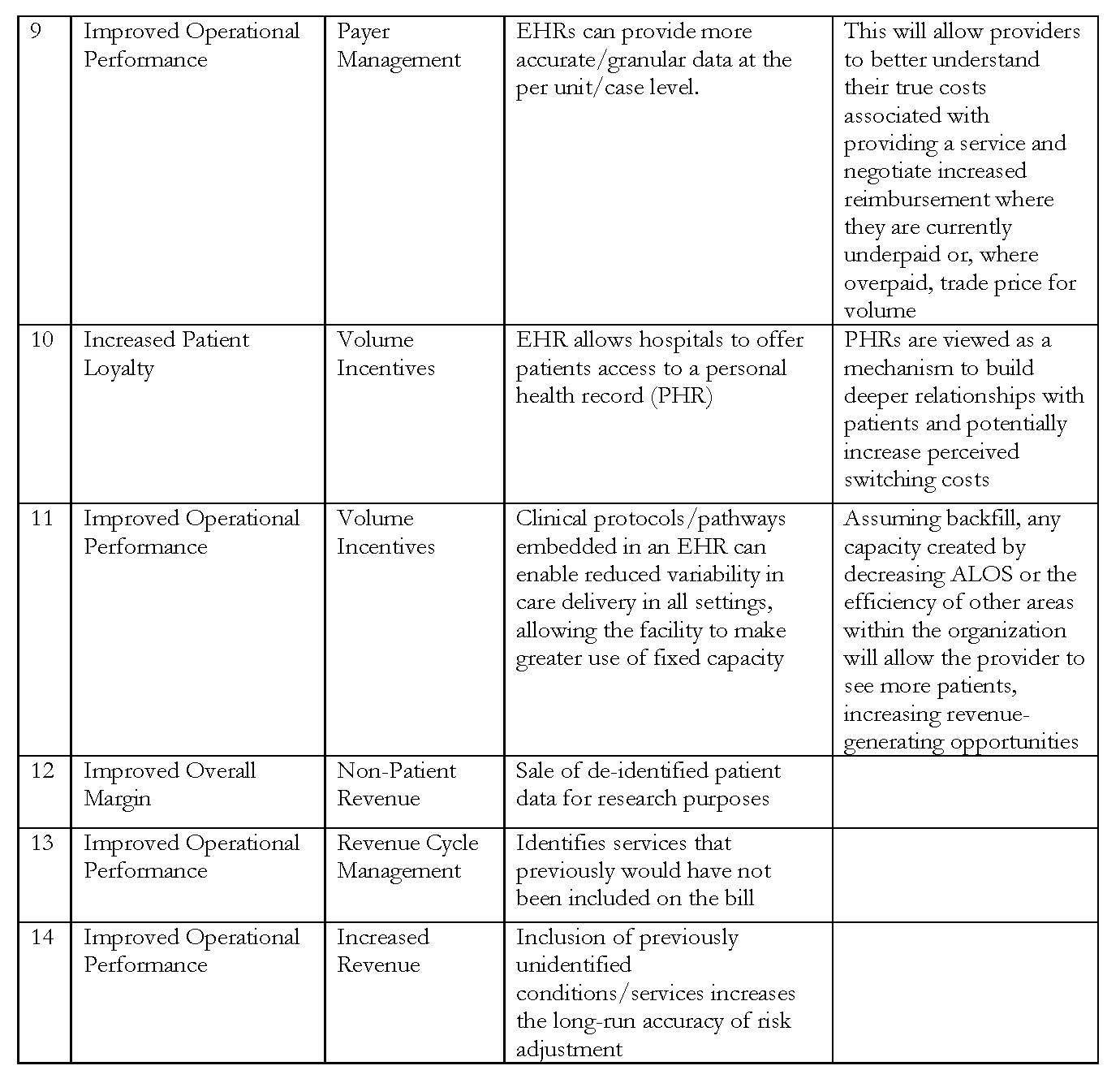

After defining the scope, the model was built over the course of several months. We held discussions by teleconference and one in-person meeting to identify potential expenses, benefits, and revenue impacts—and suggest hospital general ledger accounts where those costs (both increases and decreases) and revenue impacts might be captured. The list is not exhaustive, but seeks to provide a macro-level tool. A full list of all expenses, benefits, and potential revenue impacts included in the model can be found in Tables 3, 4, and 5.

Expenses

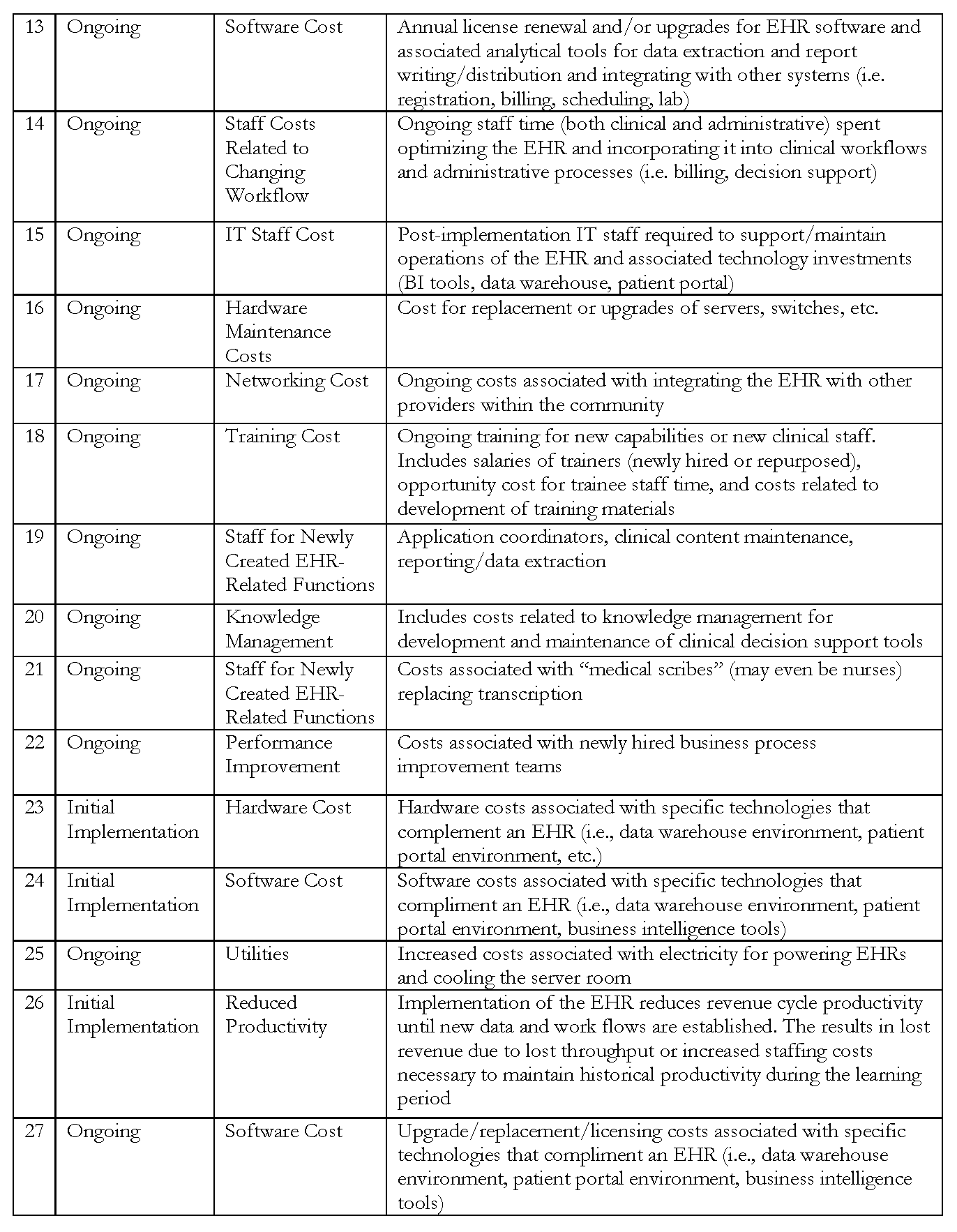

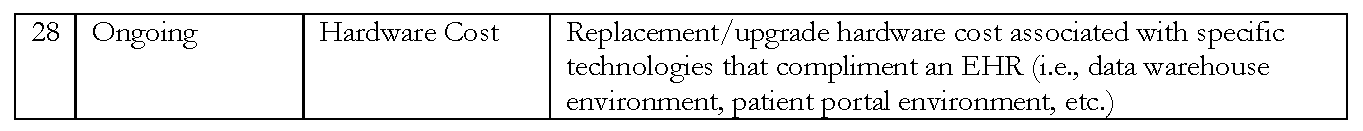

Expenses are identified by category, including productivity loss, staffing and consulting costs, technology costs, maintenance, and training. These expense categories are then organized into two types, initial implementation and ongoing, to differentiate between the one-time costs that are incurred upon initial investment, and those that will be ongoing expenses.

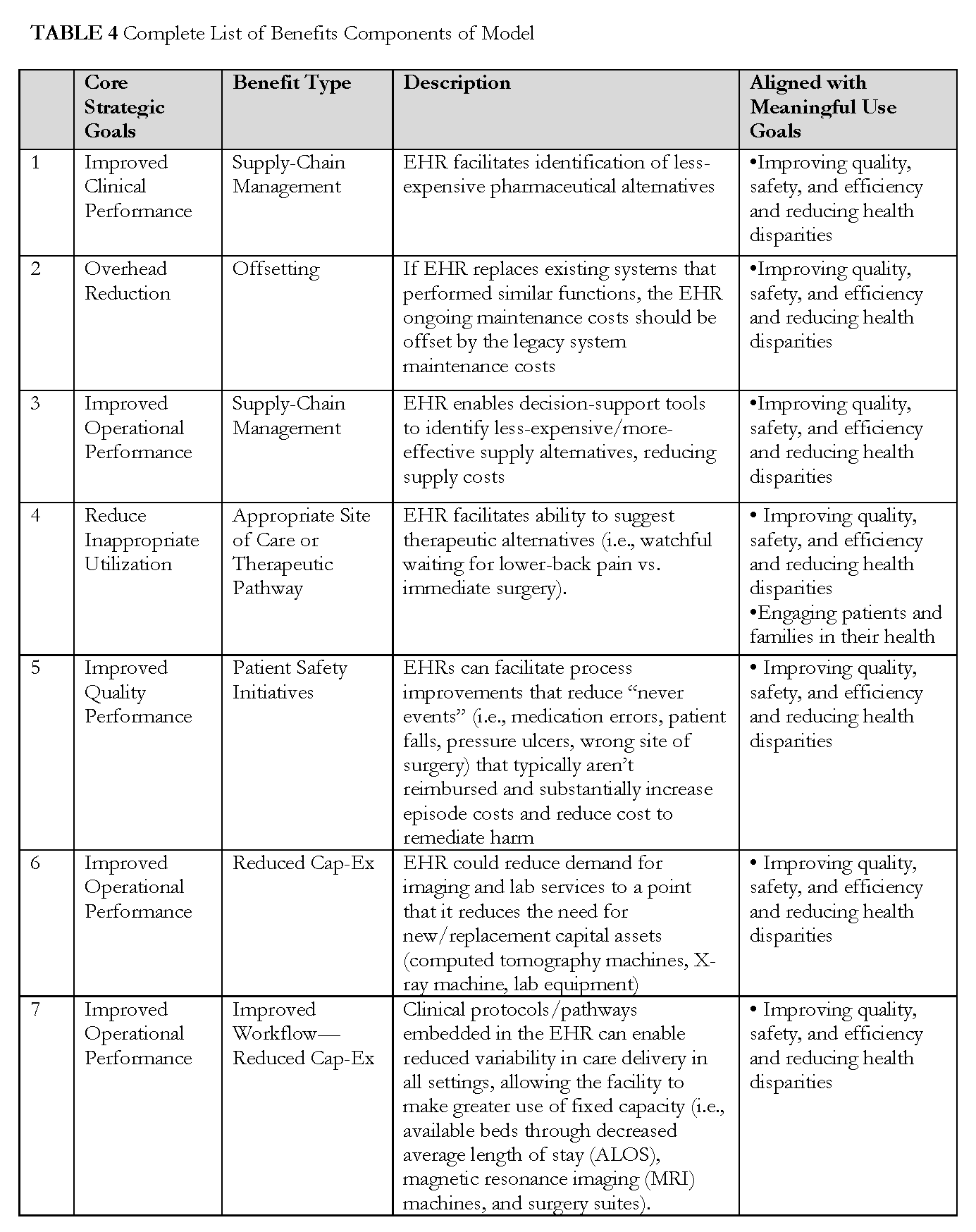

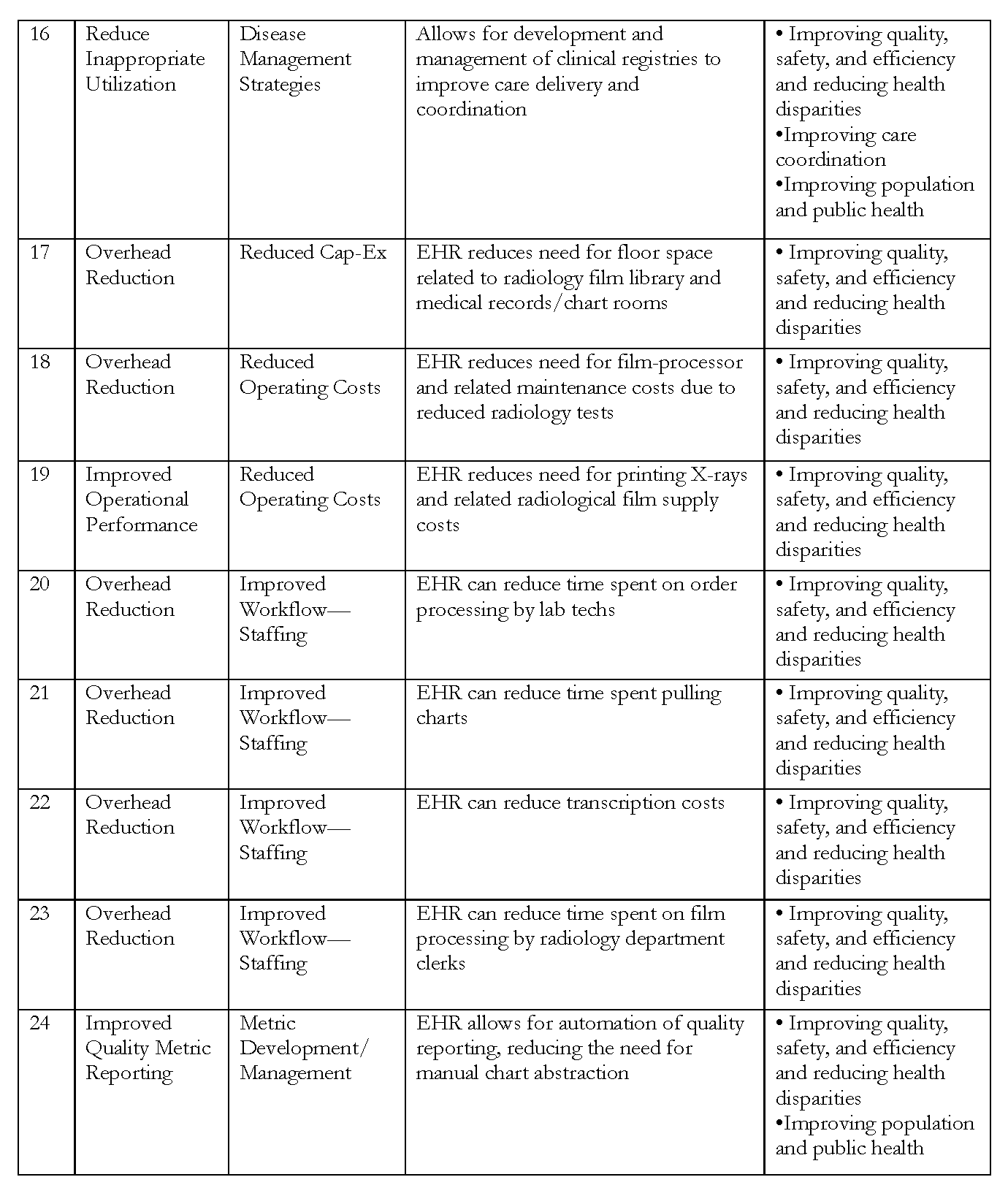

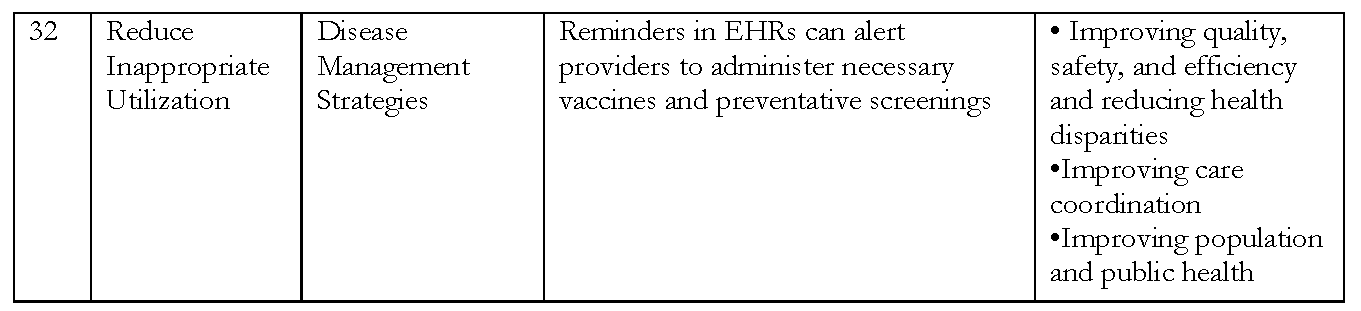

Benefits

Benefits are categorized by overall core strategic goals, including improved clinical performance, reduced overhead, improved operational performance, reduced inappropriate utilization, and support of clinical trials. These are then categorized by the type of benefit, such as reduction in administrative cost or improved use of disease management strategies. As discussed in previous sections, these include some benefits that can be easily attributed as directly to the EHR system, such as avoiding redundant lab tests, and others for which the EHR works importantly, but less directly, in achieving the improved outcome, such as reduced readmissions. Given that many of these benefits align closely with the goals of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT’s meaningful use standards, we identify those goals that closely corresponded with the benefit. We also recognize that the ability to capitalize on these benefits may differ based upon reimbursement type. Therefore, we offer a “yes” or “no” assessment of whether the benefits accrue to the provider based on reimbursement type, such as per diem or shared savings.

Revenue Impacts

Revenue impacts are categorized by overall core strategic goals, including improved operational performance and improved care coordination. We then identify specific revenue impacts, such as penalties or volume incentives, and designate them as having either a “positive” or “negative” effect.

Financial Prioritization

For both the benefits and the revenue impacts, we offered methods of financial prioritization as well as measurement methods. Financial prioritization techniques include the ability to quantify financial impact and the relative scale of financial impact. For the ability to quantify, we use the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s nomenclature to differentiate between “light green” (low ability to quantify) and “dark green” (high ability to quantify) dollars. For the relative scale of financial impact, we rank the revenue impacts from low to high.

There are several components of this model that differentiate it as an instrument to assess ROI on EHR implementation (reference numbers refer to row number in respective Tables 3, 4, and 5). From the expense side, we consider staff workflow optimization (14), which includes ongoing staff time, both clinical and administrative, spent optimizing the EHR and incorporating it into clinical work flows and administrative processes, such as billing and decision support. We also include costs related to the management of knowledge necessary for the development and maintenance of clinical decision support tools (20), and the increased costs associated with electricity for powering EHRs and cooling the server room (25). On the benefits side, our model accounts for potential benefits from the use of EHR data beyond clinical care, including to increase long-run accuracy of risk adjustment (11), to improve quality (5), to identify the highest-value setting (24/25), to identify underperforming service lines (26), and to enable auto restocking and ordering (32). Potential benefits also include strategies to increase staff efficiency and effectiveness, including embedding clinical protocols and pathways in the EHR (5/6) and enabling de-skilling strategies that allow clinicians to perform at the “top of their license” (28). The complete version of the model can be downloaded and examined at http://www.iom.edu/returnoninformation.

The primary purpose of the model is to offer providers a standardized framework for evaluating investments in health IT and related process re-engineering versus other investments that may, or may not, be value-accretive. The creation of a standardized framework offers the possibility of a secondary—and potentially more significant—benefit to providers. Given that most organizations have already invested in health IT to satisfy the requirements of meaningful use, the ability to compare the financial returns, or lack thereof, from these projects across organizations has the potential to illuminate opportunities to reduce the ongoing cost of maintaining these systems. Furthermore, the potential benefits (both cost reduction and incremental revenue increases) that can accrue from investments in health IT are predicated on significant internal care and administrative process redesign. A standardized framework will help organizations identify those redesign projects that may have the greatest financial impact. This information, along with the potential implications for patients and other stakeholders, can be considered as organizations prioritize clinical and administrative process redesign projects.

References

- Adler-Milstein, J., C. E. Green, and D. W. Bates. 2013. A survey analysis suggests that electronic health records will yield revenue gains for some practices and losses for many. Health Affairs (Millwood) 32(3):562-570. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0306

- Buntin, M. B., M. F. Burke, M. C. Hoaglin, and D. Blumenthal. 2011. The benefits of health information technology: A review of the recent literature shows predominantly positive results. Health Affairs (Millwood) 30(3):464-471. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0178

- Byrne, C. M., L. M. Mercincavage, E. C. Pan, A. G. Vincent, D. S. Johnston, and B. Middleton. 2010. The value from investments in health information technology at the U.S. Department of veterans affairs. Health

Affairs (Millwood) 29(4):629-638. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0119 - Cutler, D. 2009. Health system modernization will reduce the deficit. Available at: http://www.americanprogressaction.org/wpcontent/uploads/issues/2009/05/pdf/health_modernization.pdf (accessed December 12, 2013).

- DesRoches, C. M., D. Charles, M. F. Furukawa, M. S. Joshi, P. Kralovec, F. Mostashari, C. Worzala, and A. K. Jha. 2013. Adoption of electronic health records grows rapidly, but fewer than half of us hospitals had at least a

basic system in 2012. Health Affairs (Millwood) 32(8):1478-1485. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0308 - Fleming, N. S., S. D. Culler, R. McCorkle, E. R. Becker, and D. J. Ballard. 2011. The financial and nonfinancial costs of implementing electronic health records in primary care practices. Health Affairs (Millwood) 30(3):481-489. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0768

- Garrido, T., B. Raymond, L. Jamieson, L. Liang, and A. Wiesenthal. 2004. Making the business case for hospital information systems—a Kaiser Permanente investment decision. Journal of Health Care Finance 31(2):16-

25. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15839526/ (accessed May 25, 2020). - Hillestad, R., J. Bigelow, A. Bower, F. Girosi, R. Meili, R. Scoville, and R. Taylor. 2005. Can electronic medical record systems transform health care? Potential health benefits, savings, and costs. Health Affairs (Millwood) 24(5):1103-1117. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1103

-

Institute of Medicine. 2007. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11903.

- Kaushal, R., A. K. Jha, C. Franz, J. Glaser, K. D. Shetty, T. Jaggi, B. Middleton, G. J. Kuperman, R. Khorasani, M. Tanasijevic, D. W. Bates, Brigham, and C. W. G. Women’s Hospital. 2006. Return on investment for a

computerized physician order entry system. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 13(3):261-266. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M1984 - Konschak, C. A. G. B. 2011. The electronic health record: Is there a return on investment? Available at: http://www.vahimss.org/presentations/EMRROIPresentation.pdf (accessed July 17, 2013).

- Walker, J., E. Pan, D. Johnston, J. Adler-Milstein, D. W. Bates, and B. Middleton. 2005. The value of health care information exchange and interoperability. Health Affairs (Millwood) (Suppl Web Exclusives):W5-10-

W15-18. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.w5.10 - Wang, S. J., B. Middleton, L. A. Prosser, C. G. Bardon, C. D. Spurr, P. J. Carchidi, A. F. Kittler, R. C. Goldszer, D. G. Fairchild, A. J. Sussman, G. J. Kuperman, and D. W. Bates. 2003. A cost-benefit analysis of electronic

medical records in primary care. American Journal of Medicine 114(5):397-403. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00057-3