Paying for Population Health: A Texas Innovation

Texas’s health will more likely be transformed through an obscure set of health care reform measures called the Medicaid 1115 Waiver/Texas Healthcare Transformation and Quality Improvement Program than through the much-publicized Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA’s proposed extension of Medicaid coverage up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) has been blocked in Texas by opposition of the legislature and governor, hile early technical failures of the ACA’s “health insurance marketplace” have hampered extending commercial insurance to 100-400 percent of the FPL. In contrast, the Medicaid 1115 Waiver was amicably agreed to by both Republicans and Democrats, cooperatively designed by the Texas Department of State Health Services and the U.S. Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services, and is already being widely applied by local hospitals, academic medical practices, mental health providers, and public health departments.

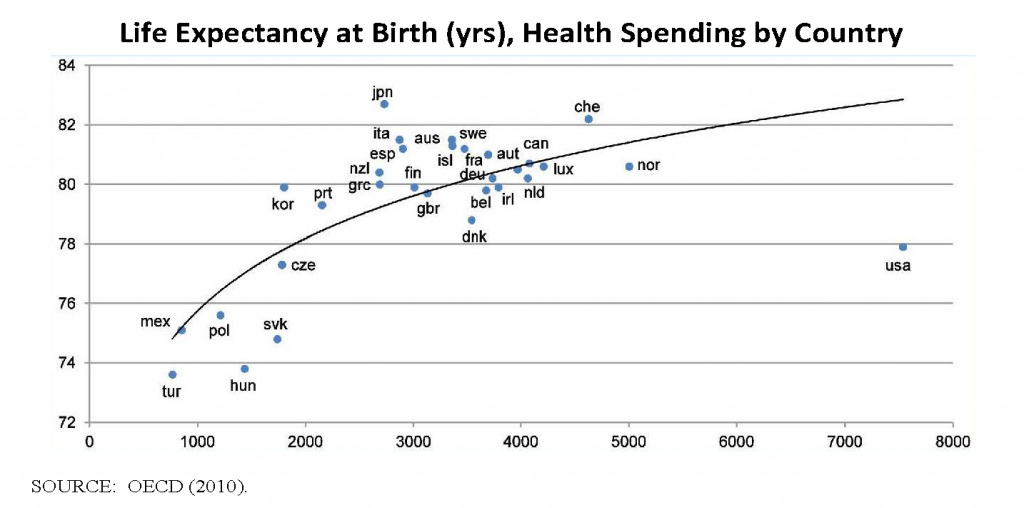

The ACA, fully realized, would provide health insurance coverage to the majority of Texas’s 6 million uninsured residents—undeniably a very good thing. But the ACA will not greatly change the basic structure and function of the poorly organized and dysfunctional U.S. health care system. The Medicaid 1115 Waiver, on the other hand, goes beyond funding preventive screening, counseling, and vaccination to fundamentally change system goals and incentives. The need for fundamental change is demonstrated by the graph below, which shows that the United States spends annually approximately twice as much per capita ($8,000 vs $4,000) as any other country in the world to achieve outcomes that are described as merely “lackluster” (IOM, 2012a).

Further, health spending in the United States has been disproportionately increasing for decades and currently consumes 18 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, almost $3 trillion per year.

Medicaid, a $436 billion federal and state health care program for low-income individuals and families, is a significant and growing part of overall health spending. Section 1115 of the Social Security Act authorizes that certain Medicaid requirements may be waived to allow for reallocation of funds to promote Medicaid’s objectives and save states’ money. Many states have employed the 1115 Waiver to move toward managed care models and expand Medicaid coverage to more individuals, particularly low-income adults with and without children. But, to date, no state appears to have used the waiver in the way that Texas has.

Of states that use the waiver to expand the Medicaid-covered population, most shift the greater proportion of those covered to public and private managed care or accountable care organizations that provide necessary medical services for a fixed, monthly payment. Such “capitated rate” financing has been shown to be profitable for provider organizations, money-saving for states, and conducive to better health outcomes. Although Texas rejected ACA promoted expansion, it used the Medicaid 1115 Waiver in a way that may have an even greater long-term benefit. In Texas, 10 percent of the Medicaid budget of $25 billion will be redirected annually away from the ever-increasing “black hole” of diagnosis and treatment of the ill, injured, and worried well and toward front-loaded programs to improve the quality of medical care, increase access to services, and promote population-based prevention to keep people healthy. Significantly, 5 percent of the total amount is earmarked for local public health. The beauty of these programs is that they will benefit the entire population, regardless of income. In no other state has such a shift toward prevention occurred. The hope is that true health care, as opposed to “sickness care,” will chip away at the 30 percent of current health care expenditures the Institute of Medicine has described as being “wasted on unnecessary services, excessive administrative costs, fraud, and other problems” (IOM, 2012b) and will, over time, transform the health of the people of Texas.

In south Texas, 25 partners, including the San Antonio Metropolitan Health District (SAMHD), are investing $1.16 billion of Medicaid funding through 2016. The partnership’s goals are to reduce inappropriate emergency room use, repeat hospitalizations, and complications of chronic diseases like diabetes. Especially, partners aim to prevent illness and injury by promoting healthy living. SAMHD will spend up to $43 million in new Medicaid funding on six new prevention programs. First, in collaboration with Healthy Futures and UT (University of Texas) Teen Health, SAMHD is greatly expanding its teenage pregnancy–prevention efforts by extending scientifically based, abstinence-plus curricula to 23 middle schools; initiating case management of teen moms to avoid subsequent unplanned and unwanted pregnancies; connecting sexually active teens to safe, reliable, long-acting, reversible contraceptives; and supporting local physicians who want to make their practices more accessible to and effective for adolescents. Second, SAMHD is partnering with the YMCA to offer scientifically validated obesity and diabetes prevention programs. These will be offered free of charge to 500 area residents. Third, SAMHD is piloting grassroots organizing to prevent obesity through better nutrition, physical activity, and enhancements to the built environment in 10 neighborhoods. Fourth, the SAMHD Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program will soon open a “Baby Café” where any pregnant woman or new mom, not just WIC clients, can learn how to start and sustain breastfeeding, the first step toward good nutrition. Fifth, SAMHD is greatly expanding school-based oral health clinics, which address the most widespread of all health problems: dental caries. Finally, SAMHD is remaking its sexually transmitted disease clinic and reaching out to population groups that are driving a local syphilis epidemic. During the past 2 years, new cases of syphilis among adults have broken all records. Most tragically, San Antonio leads the nation in babies born with incurable congenital syphilis: 32 since January 1, 2012.

The return on investment of some of these interventions is easy to calculate. Congenital syphilis babies, if they survive, generate hefty medical expenditures during the first few months after birth and often have lifelong disabilities that require further treatment and lead to learning disabilities, problems at school, asocial behaviors, chronic unemployment, and other costs to society. In another example, each teen birth costs an estimated $22,000 in hospital charges, child welfare, incarcerations, and lost revenue. The reduced number of teen births in Bexar County, Texas, in 2012 (as compared to 2008) saved taxpayers approximately $23 million. Other returns on investment, such as the lifetime benefits of maintaining a healthy weight, effective diabetic self-management, and good dental health are more difficult to estimate. Nevertheless, prevention, the commonsense approach to myriad health problems, is being broadly embraced in Texas. Of all places! Will this radical, multibillion-dollar experiment be allowed to continue beyond 2016? A great deal depends on our ability to demonstrate results. We have 3 years to do so.

References

-

Institute of Medicine. 2012. For the Public’s Health: Investing in a Healthier Future. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13268

- Institute of Medicine. 2013. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13444

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2010. Health Care Systems: Getting More Value for Money. OECD Economics Department Policy Notes, No. 2. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/eco/growth/46508904.pdf (February 5, 2014).