Inaugural DC Regional Public Health Case Challenge: A Summary

In 2013, the Institute of Medicine (IOM), in collaboration with faculty and students from Georgetown University (GU), launched the first annual District of Columbia (DC) Regional Public Health Case Challenge. The idea for this case challenge was born when representatives from the IOM and GU met at Emory University’s Global Health Case Competition in March 2013, and the DC Case Challenge is both inspired by and modeled on the Emory competition.

The DC Case Challenge aims to promote interdisciplinary, problem-based learning in public health and to foster engagement with local universities and the local community. The case challenge engages graduate and undergraduate students from multiple schools, disciplines, and universities to come together to promote awareness of and develop innovative solutions for 21st-century public health issues, grounded in a challenge faced by the local community.

Each year the organizers and a student case-writing team develop a case based on a topic that is not only relevant in the DC area, but also has broader domestic and global resonance. Universities located in the Washington, DC, area are invited to pull together teams of three to six students enrolled in undergraduate or graduate degree programs. In an effort to promote public health dialogue among a variety of disciplines, each team is required to have at least three different schools, programs, or majors of study represented.

Starting 2 weeks before the case challenge event, these teams are asked to employ critical analysis, thoughtful action, and interdisciplinary collaboration to innovate a solution to the problem presented in the case. On the day of the case challenge, teams present their proposed solution to a panel of judges composed of representatives from local DC organizations as well as other subject matter experts from disciplines relevant to the case. In addition to the panel of judges, content experts are recruited to volunteer their service as reviewers to assist the student case-writing team.

2013 DC Case: Violence Against LGBT Youth

The 2013 case focused on violence against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth living in the Washington, DC, area. The case asked the student groups to develop a program for less than $200,000 that would fill a void in interventions intended to reduce violence or to provide services to youth experiencing violence. Each proposed solution was expected to offer a rationale, a proposed intervention, an implementation plan, a budget, and an evaluation plan.

The case framed the issue through three examples of targeted violence: in one, a 19-year-old transgender woman was stabbed repeatedly by two men in a hate crime; in another, an 18-year-old bisexual female committed suicide after having been bullied at school and at home; in the third, a 21-year-old gay male was hospitalized after suffering from both domestic and emotional abuse by his partner. Though all three cases were fabricated, they were based on real events involving LGBT youth living in DC.

The case challenge packet provided DC demographics, youth-targeted crime statistics, and statistics on national and local bullying trends. The case also outlined drivers of violence targeted at LGBT youth and broke down the repercussions LGBT youth face relating to both mental and physical health. Such repercussions included substance abuse, suicide or suicide ideation, eating disorders, missing class, and running away from home, among others. Among other resources, the case featured the IOM report, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding.

Each of the seven solutions was thoughtful, thoroughly researched, and well presented. Each team’s presentation was wholly unique, but converged at two main areas of intervention. Several solutions focused on preventing LGBT youth from being bullied, and the others on creating safe spaces for homeless LGBT youth. The following student-written synopses describe how teams identified a priority need, formulated a solution to intervene, and would implement their solution were they to be granted the fictitious $200,000 allotted to the winning bid in the case.

Team Case Solutions

The following section contains two-page summaries of the proposals of six of the seven teams that participated in the 2013 case challenge.

American University

Nicolette Davis, Alexandra France, Aapta Garg, Kara Ingraham, Kristen Rankin, Karanpreet Takhar

Targeting Violence against LGBT Youth in Washington, DC: A Three-Pronged Approach

The following intervention addresses the pervasive issue of violence against LGBT youth in Washington, DC, in school and community environments. Six in ten LGBT-identifying youth nationwide reported that they felt unsafe in school, while 4 in 10 report physical harassment (CDC, 2009). Peers may not know how to appropriately stop violence or harassment linked to perceived sexual orientation. Teachers, school staff, and law enforcement are often ill-equipped to address these issues, with teachers in a recent study reporting a lack of institutional backing in their attempts to support LGBT students (Durso et al., 2013). Our three-pronged approach seeks to alleviate these issues, in which the overall goal is to reduce both physical and emotional violence toward the LGBT youth population. Additionally, each of the three prongs is designed with sustainability in mind, with the intention of reducing long-term symptoms of marginalization and violence by increasing community-level awareness and accountability.

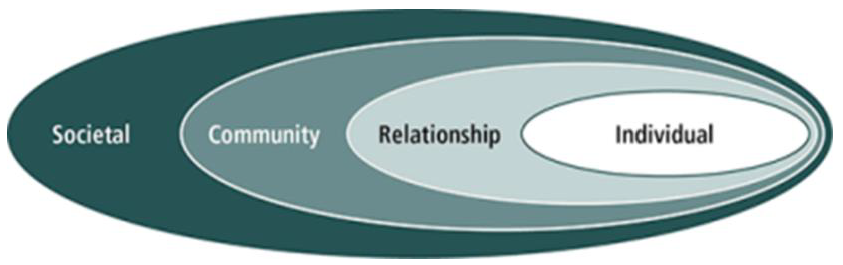

In this multilevel approach, we target three populations: teachers and staff of three area high schools, the general student population, and the DC Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). Within these target populations, the intervention addresses determinants of violence on four levels: the individual, the interpersonal, the community, and the population levels. On the individual level, the intervention aims to change attitudes toward and awareness of LGBT issues. On the interpersonal level, it would increase the likelihood of bystander recognition of and intervention in violent situations. On the community level, in both personal and professional environments, it seeks to foster safe spaces and a sense of community. Finally, on the population level, the intervention would create increased awareness and acceptance of personal differences. The overall intended health outcome is to reduce violence against LGBT youth in all aspects of life.

Sustainably combating violence against LGBT youth mandates addressing the root cause, which manifests itself in both physical and emotional violence. This three-pronged intervention addresses oppressive gender norms and social constructs that create hostile school and community environments for LGBT youth.

First Prong: Bystander Intervention: Targeting Peers

The first prong in this approach is the implementation of bystander intervention workshops within select schools in the DC metro area. These workshops establish a curriculum that challenges oppressive gender and sexual norms, while simultaneously providing students with skills to intervene against acts of violence in productive ways. To do so, we advocate for creating a partnership with AmeriCorps to bring in volunteers to carry out a 10-part curriculum in classrooms. Using the curriculum, volunteers will clarify norms and values, discuss concepts of sexual identities and gender constructs, and address violence and its prevalence in students’ lives. We will culminate the activity by creating strategies for action.

Second Prong: Safe Space Campaign

The second prong to our intervention involves the implementation of a Safe Space Campaign modeled on the DC Public Schools (DCPS) 2011 Plan to Create an Inclusive School Community (DCPS, 2011). We focus on DCPS’s call to equip administrators and teachers with effective strategies for intervening in situations of violence against LGBT, with the ultimate goal of creating safer, more inclusive school climates (DCPS, 2011).

In collaboration with existing LGBT school liaisons, we will develop an online Safe Space toolkit and training course with curricula adapted from lesson plans designed by a DCbased non-profit, Advocates for Youth (Advocates for Youth, 2013. This online work will be supplemented with interactive lunchtime workshops for teachers to engage in dialogues on creating safer school communities responding to instances of bullying and emotional violence.

Third Prong: MPD Strategy

Because police officers are often the first to respond to violent situations, our third prong involves the DC MPD. Police officers acting in instances of violence against LGBT youth often report having insufficient knowledge of these youth’s unique contexts, and therefore feel unprepared to address related issues (Cannon and Dirks-Linhorst, 2006). One study cites police officers feeling as though they were supposed to act as youth counselors, a role for which they do not have adequate training (DeJong et al., 2008). To address these issues, we capitalize on the existing continuing education framework within the MPD system to prepare police officers to adapt and respond appropriately. We plan to partner with the MPD Gay and Lesbian Liaison Unit and Continuing Studies Bureau to create a comprehensive continuing education course for police officers to take as a part of their 32-hour requirement to retain their MPD licensure. The course will include advanced sensitivity training and highlight strategies for response to situations of violence against LGBT persons.

Budget Overview

To implement a cost-effective, holistic intervention, this strategy has built-in measures to keep operational costs as low as possible. We plan to use a substantial in-kind contribution from AmeriCorps to employ nine full-time VISTA volunteers, who will take lead roles in the Bystander Intervention component of the intervention. A single project manager will be hired to manage all three components of the intervention. Thus, our budget remains well within the $200,000 constraint allotted for the 3-year period.

Limitations and Barriers

Limitations and potential challenges of the intervention include language requirements, partner buy-in and cooperation, and measurability. All three curricula developed need to be available in both English and Spanish so they are accessible to the diverse target population living in Washington, DC. Furthermore, the success of these interventions depends largely on how much buy-in and cooperation there is from DCPS and MPD. Lastly, given the structure of the interventions, measurability may pose an issue as there is a heavy reliance on self-reporting. Collecting feedback from families and reaching young people who are regularly absent from school may also prove difficult. Although these challenges seem daunting, the intervention is designed to be a fluid and evolving series of components, with flexibility for adaptation as necessary. In all, the components of this intervention have been thoughtfully designed with the end goal of reducing violence against LGBT youth.

George Mason University

Zoya Butt, Stephanie Campbell, Iqra Javaid, Lindsey Miller, Laura-Allison Bohannan Woods

LGBT youth experience much higher levels of physical and sexual violence compared to their non-LGBT peers, and hate crimes targeted toward this population are alarmingly frequent. This necessitates the need for a set of interventions that will improve the treatment of LGBT youth in DC.

Our solution aims to create a program that will reduce violence targeted toward LGBT youth over the course of 3 years in high schools in Wards 7 and 8. We have chosen this approach because it is both feasible with regard to funding and has a high likelihood for future sustainability.

The target population for our intervention is LGBT high school students, ages 14-18. Schools, in particular, are often dangerous and hostile environments for LGBT youth. Crime rates toward LGBT youth living in DC are highest in Wards 7 and 8 (DC MPD, 2013). In addition, Wards 7 and 8 are 96 percent African American, allowing for an isolated intervention and examination of one LGBT high-risk violence group. We chose to implement our program within three different high schools within Wards 7 and 8.

Understanding underlying theories and motivations that lead to bullying must be understood when creating sustainable interventions. Some explanations for bullying view it as both an outcome of differences and, from a restorative justice perspective, an act of mismanaged emotions (Rigby, 2004). Bullying that occurs because of individual differences results in the domination of the less powerful child by the child deemed more powerful or possessing more favorable traits. When bullying stems from acts of maladapted emotion management, adolescents do not experience typical feelings of shame from causing others emotional distress and, when victimized, feel an exaggerated sense of shame (Rigby, 2004).

Our intervention focuses on these two theories as a starting point for reducing the incidence of bullying. We also take into account the power of peer interactions, and the possibility that students can be conditioned and influenced by each other to react positively in potential bullying scenarios. By applying the ideas of restorative justice, the intervention focuses on social networks to prevent bullying.

The intervention consists of several components, which include plans to implement Gay–Straight Alliances (GSAs) within the school network, a media campaign with the original slogan “Don’t Be a Hater,” and a faculty education program that addresses youth violence at the source of school authority.

According to the American Psychological Association, GSAs can benefit students by providing them with a greater sense of belonging, reducing the frequency of hearing homophobic comments, reducing harassment and assault, and increasing student comfort with reporting incidents of harassment and violence to school administrators (Rigby, 2004). GSAs work primarily as a student organization in which both LGBT-identifying students and straight identifying students can work in conjunction with educators to reduce stigma in the school setting. GSAs also provide school-wide education regarding LGBT treatment and tolerance.

The “Don’t Be a Hater” campaign aims to maintain a culturally and socially appropriate approach, and relies on students to promote anti-bullying messages among their peers. It is administered in tandem with the GSAs as a program agenda intended for the students to take as their own. The “Don’t Be a Hater” campaign addresses external educational forces through social media, including Facebook, Twitter, flyers, and YouTube, all of which are an effective use of a limited budget as they are relatively inexpensive. The program is likely to be sustainable because it offers personal contributions and shows enthusiasm by the students themselves. Below are examples of two graphic designs for the “Don’t Be a Hater” campaign, which could be posted on social media.

Finally, the faculty education program directly trains school educators and staff on how to handle violence aimed at LGBT youth. In addition to their instructional responsibilities, it is essential that teachers and administrators are cognizant and comfortable in addressing any violence that may occur within their jurisdiction. The faculty education program is brief, but is designed to give each educator a comprehensive understanding of how to identify the appropriate internal and external resources available to LGBT youth and refer students to these if the situation mandates. Educational information will include LGBT youth health risks, bullying awareness, identification of invested staff to advise GSAs, and appropriate internal and external resources for referrals.

This program is designed to build potential partnerships with the DC Department of Health (DOH) and the DC-based nonprofit organization, Supporting and Mentoring Youth Advocates and Leaders (SMYAL). DC’s DOH has a Violence Prevention Program that is an ideal partnership because it focuses on reducing sexual violence in Wards 7 and 8. Topics covered by VPP include bullying, cyberbullying, harassment, depression, and suicide prevention. Evaluating the relationship between DC’s DOH and the public school system will allow the development and implementation of the “Don’t Be a Hater” program to follow standard guidelines already in place. SMYAL is a similar program that reaches out to youth centers and public schools to address negative health outcomes. This affiliation will allow students to build a relationship of trust and security within and outside of the school system for persistent issues involving violent behavior. Overall, building partnerships with these programs will cater to the educational and interpersonal needs of LGBT youth and school staff onsite.

Georgetown University

Chandani Desai, Suzanne Keck Huszagh, Claire Lang, Darshana Prakasam, Megan Prior

LGBT youth in DC are currently subjected to emotional and physical harassment, which has subsequently led to a host of problems that include, but are not limited to, intolerant school environments, homelessness, intimate partner violence, and decreased mental and physical health. To address this issue, we looked at primary, secondary, and tertiary models of disease prevention. Successful actions could 1) prevent violence from happening in the first place, 2) address the effects of violence before symptoms surface, or 3) focus on treatment of the recognized post-traumatic effects of violence. We propose a primary intervention in the form of a curriculum and social media campaign to empower bystanders to speak out against violence committed toward LGBT youth.

Segmenting the youth population to include individuals ages 15-24, four groups emerge: high school students, college students, young professionals, and individuals who are unemployed and/or not currently attending school. Our proposed intervention specifically targets high school and college students. By introducing a curriculum into high schools, we hope to empower students as bystanders and discourage violence. Meanwhile, college students are encouraged to help change the culture surrounding LGBT youth violence by developing and disseminating the curriculum to high schools.

Our intervention is based on that used by Health Leads (www.healthleadsusa.org), an award-winning organization that trains college students to serve as resource coordinators in underserved settings. In the Health Leads model, a paid organizer recruits college students and supports them to work in clinics. Translated into our program, a paid education coordinator would recruit and train DC area college students to teach a high school curriculum that aims to reduce violence against LGBT youth.

Interventions that promote safety for LGBT youth in schools can be categorized into three domains (Roman, 2013):

- Increasing safe space for LGBT students;

- Increasing punishment for bullies; or

- Educating bystanders.

For our curriculum, we selected bystander education because of its powerful evidence base. One study, conducted in Finland, evaluated the implementation of a bystander curriculum with a randomized controlled trial in 234 schools (Kärnä et al., 2011). Both self-reported and peer-reported bullying—including that conducted on the Internet—were reduced significantly (Salmivalli et al., 2011). Anxiety and depression also decreased and students reported a more positive peer environment (Williford et al., 2011).

DC has several pieces of existing infrastructure into which we would incorporate our bystander empowerment curriculum. The DCPS Office of Youth Engagement released “A Plan to Create an Inclusive School Community,” which details the district’s efforts to increase safe spaces, resources, and reporting for LGBT youth (DCPS, 2011). The public school system has also established an antibullying advisory committee of experts to facilitate the implementation of bullying prevention projects in schools. Augmenting these existing programs with bystander empowerment would enhance their effectiveness.

Next, all major universities in the region have LGBT resource centers present on campus that serve as information hubs for college students. These established centers would allow us to recruit interested and qualified candidates to help create and teach the curriculum.

Finally, the DC government passed the Youth Bullying Prevention Act of 2012 that requires all district agencies, grantees, and educational institutions to adopt a bullying prevention policy. A task force charged with implementing this law released a report in 2013 with best practices, in which bystander curricula were included.

Year one of our program is devoted to capacity building. An education coordinator would be hired to develop the curriculum and the evaluation plan. He or she would be in charge of coordinating the university programs and engaging the participating high schools. A social marketing coordinator would also be hired during the first year. This individual would be responsible for creating the website, developing a state-of-the-art social media campaign, and maintaining a constant and engaging social media presence. We recognize that there are many agencies within the DC government, such as DCPS and the Charter School Council, invested in education and gender-based violence, and we plan to collaborate and coordinate with them starting in the first year to develop a sustainability strategy for the project. We would also involve them in developing a steering committee.

Year two is devoted to implementing the program. This includes monthly training sessions with university volunteers, lessons in participating DC high schools, and a continual marketing campaign and social media presence. We plan to evaluate the program throughout the entire 3 years, and would administer surveys throughout the second year to monitor the program’s progress. The third-year includes data analysis, the implementation of any changes based on the data, and the expansion of the program into additional high schools. We would also want to advocate for a permanent funding mechanism during this year.

The core undertakings of our intervention include the formation of a multidisciplinary coalition; leadership development; a targeted, engaging curriculum; empowerment of the target group; and the development of an online movement to end violence and bullying against LGBT youth in the DC community. An overview of the specific activities to be taken in each of these five core areas is highlighted below:

- Multidisciplinary Coalition: Enhanced local partnerships involved in violence prevention, enforcement, and reentry

- Leadership Development: College youth will be trained in curriculum development and digital media through problem-based learning

- Developing a “Cool” Curriculum: College youth will produce peer-targeted, bullying-related activities, digital content, articles, and films

- Empowering Peers: College youth will conduct educational seminars and deliver targeted messages on violence and bullying to freshmen in DCPS

- Spreading the Message: Content pertaining to violence, bullying, and community resources will be uploaded continuously to the campaign website

The goal of our intervention has three tiers. In the first phase, we believe our intervention will help individuals gain awareness, knowledge, and skills that will lead to a positive change in attitudes on and around the issues of LGBT violence and bullying. In the second phase, we believe that individuals will learn to incorporate the learned skills into real behavioral changes, shifting the populace from taking a passive bystander stance and approach to these issues to becoming an active bystander that actively advocates for the reduction of violence against LGBT youth and for the reduction of bullying in the educational system and in the community. In the final phase, we believe that LGBT individuals will actually experience and perceive a positive change both in the way they are being treated in school and in the way that their community is working to support them.

We will evaluate the success of our intervention by collecting information pertaining to college youth engagement, bystander activation, and improvement(s) in educational environments. Categories of measures to be included are college youth engagement, increased bystander activation, and improvements in the educational environment.

Howard University

Desiree Bygrave, Christine Clarke, Ariel Gaines, Victoria Larsen, Aubrey Palmer, Ariel Turner

Violence against LGBT youth is particularly prominent within two contexts: schools and communities. Chief among the challenges faced by LGBT youth in the school environment is discrimination and verbal harassment, bullying, and an overall lack of support from teachers and staff and fear for personal safety. Within the community context, however, these challenges include homelessness, hate crimes, police misconduct, and verbal and physical harassment.

We outline several programs aimed at addressing the challenges intrinsic to the LGBT youth population. Several of our proposed interventions complement existing strategies by strengthening perceived weak/unaddressed areas. These interventions are the School Sensitivity and Cultural Competency Training, Group Outreach Education, and Online Police Sensitivity Training. We also propose several interventions that are new to the DC area: the Online Bullying Reporting Tool, Host Homes, and the “Love, DC” Community Outreach Campaign.

School Sensitivity and Cultural Competency Training

A School Sensitivity and Cultural Competency Training is a training program that aims to increase cultural awareness of and sensitivity to LGBT-specific issues among staff and the student body. It introduces a curriculum that covers a range of topics/terminologies and concepts surrounding LGBT issues such as abuse/harassment and discrimination. LGBT culturally competent community members, and individuals employed by Metro Teen AIDS, a non-profit organization located in DC, train faculty, school counselors, and students to facilitate the training program.

Group Outreach Education

The Group Outreach Education program entails group meetings between LGBT college and high school students. By facilitating an information exchange on topics affecting the LGBT youth community (healthy vs. unhealthy = relationships, assertiveness skills, violence types and warning signs, combating violence in the home), the group outreach education provides mentorship and a social support network for LGBT youth of all ages. Additional sessions orient and offer guidance to parents on supporting and accepting the LGBT youth community.

Online Police Sensitivity Training

Our Online Police Sensitivity Training is a mandatory training that requires police officers to engage in and receive accreditation for an online training designed to increase their sensitivity and competence in dealing with misconduct among LGBT civilians. The training decreases mistrust between LGBT community and law enforcement and decreases reports of police misconduct among LGBT-identifying civilians.

Online Bullying Reporting Tool

The Online Bullying Reporting Tool provides a safe and anonymous web-based mechanism for reporting bullying incidents—the intended outcome of which is to provide more accurate statistics on bullying trends. The reporting tool is a low-resource, low-budget method that targets high school students, ages 14-19, and facilitates reporting of bullying incidents that occur on school property, at school-sponsored events, or online. It provides a safe “reporting space” for students for whom face-to-face reporting is uncomfortable and discouraging, while capitalizing on the demographic proclivity toward online communication mechanisms. The online reporting tool constitutes a bullying reporting form based on the Sprigeo reporting tool (The Sprigeo Effect, 2013). The form is strategically placed in a conspicuous and designated area of the school’s website—for example, a Student Health Page—providing easy access to students who may be victims of or witnesses to bullying. Survey questions are tailored to determine details such as names of students involved, date of incident, incident location, description of incident, physical injury, and specific nature of the bullying incident.

The accompanying web page/online form also has an upload feature to allow addition of screenshots, pictures, etc., thereby providing a more accurate depiction of the bullying incident. The generated incident report is forwarded to the designated counselor, who then investigates and addresses the problem using the appropriate mechanisms (law enforcement or otherwise). The school-based online bullying reports are incorporated on an ongoing basis into larger reporting databases established by organizations such as the Youth Bullying Prevention Task Force, which was created under the Youth Bullying Prevention Act. Additionally, at the end of the year, schools report actions taken for each school-related bullying incident, as well as actions taken for incidents reported via the online form. The Task Force also receives the annual reports.

Despite the anonymity that the online reporting tool affords, it may not be used by subgroups that, though appreciative of the safe reporting space, may view the tool as lacking the human element that encourages reporting. Additionally, if there is a relatively high volume of online reports, it may be difficult to appropriately sort incidents such as hate crimes that may warrant immediate attention. Consequently, there may be a significant time-lapse between reporting and identification of these specific cases that warrant urgent attention. Therefore, designing the online tool with optimized sorting capabilities may be a challenge.

DC Host Homes Program

The DC Host Homes Program will offer an immediate solution to the increasing number of LGBT homeless youth in DC. By matching youth across the District with volunteer members, the DC Host Homes Program provides safe and supportive housing, with individualized post-violence intervention, counseling, and mentorship. The DC Host Homes Program is conceptually similar to the Avenues for Homeless Youth Program in Minneapolis, MN (Avenues for Homeless Youth, 2011), and is a way to increase the number of safe houses through community involvement while providing mentorship to LGBT youth as they transition from host home to independent housing, or higher education. The program also provides a transitional living environment for LGBT youth who may not feel safe or welcomed in traditional homeless shelters, or who may have “aged out” of the foster care system. Furthermore, the program complements existing LGBT-friendly homeless shelters faced with inadequate facilities such as beds for youth. Host Homes will be geared toward prospective youth whose age, at the start of the program, will range between 16 and 21, and will promote a maximum stay of 2 years with a possible chance of renewal.

A Host Home Council will be formed using appointees by the DC mayor’s office, LGBT allies, and human rights campaign representatives. Using their established criteria for youth and host family volunteers, the council will match eligible youth with suitable host families. Over the course of a maximum 2-year stay with their host, youth will be provided with individual counseling, and hosts will be provided with counseling and training on ways to best support their youth match. Counseling and training services will be provided on a volunteer basis by community organization partners such as the Whitman-Walker Health Clinic and Family and Medical Counseling Service, Inc. In its first years, small-scale advertising at LGBT-focused youth centers and organizations and through social media will connect potential homeless youth and hosts with the host home council. The program will be evaluated by scheduled check-ins by the host home council and individuals involved in providing counseling services with youth and hosts, annual evaluations of the program by youth and hosts, the number of youth transitioning to independent living, and the overall change in rates of homelessness after the initial start-up period.

Potential setbacks to this program may include the time it may take to identify qualified volunteers who are willing to sit on the host home council; the time it may take to formulate program eligibility criteria and to schedule check-ins; difficulty in finding enough host home families who meet eligibility criteria and are willing to participate, as well as initial rallying of community support and donations. Despite these potential setbacks, by the end of the first year, the appropriate methods to combat these challenges will, however, be implemented, once the program is underway.

Love, DC

The “Love, DC” Campaign is an overarching community outreach campaign—the mission of which encompasses all the goals and activities of both the school- and community-based recommendations. The campaign constitutes the use of a mobile app and stickers bearing the “Love, DC” logo (below). Participating locations place the sticker in their windows and on their websites as a visible statement to indicate that they are LGBT-friendly/safe zones. The mobile app may then be used to find these locations.

The mobile app is a geographical, color-coded map of the District and its wards, which uses real-time information to increase awareness of LGBT-friendly/safe locations, organizations, and businesses. Maps will provide information on hate-crime statistics and crime density, as well as information on shelter and safe-house locations, HIV-testing facilities, and LGBT-friendly health care providers. The mobile app’s strength is in the provision of real-time information, thereby providing trusted information about the safety of a location for LGBT youth.

The campaign promotes inclusivity and nondiscriminatory practices in the policies, code of ethics, and services provided by the participating businesses and organizations. It promotes trust between the LGBT youth and community, increases feeling of safety, identifies LGBT allies closest to a person’s location, and increases awareness of recent hate crime incidents in the District.

The effectiveness of the app will be evaluated based on the number of downloads, as well as the number of businesses and organizations enrolled to have their information represented or used in the app. The app may also be integrated with the Department of Health’s LGBT program and policy initiatives. The stickers, also a major component of the “Love, DC” Campaign, will be distributed by the District, free of charge, after a thorough review of policies and codes of ethics of participating businesses or organizations. The sticker, designed to reflect a heartfelt letter from the DC community, is represented by a silhouette of the District, overlaid with a heart, and inscribed, “Love, DC.” The red backdrop symbolizes love, and serves as a call to action.

U.S. Naval Academy

David Brainerd, Adam Hammer, and Chelsea Schifferle

Due to discrimination from their community and even their family, LGBT-identifying youth commonly experience homelessness. This puts LGBT youth at significantly higher risk of violence, substance abuse, and sexual victimization. Many LGBT youth experiencing homelessness are turned away from homeless shelters due to the shelters’ inability to care for them, creating a gap between the LGBT youth experiencing the most violence and the care that they need. To most efficiently start the movement away from violence against LGBT youth in DC, we will focus on closing this gap.

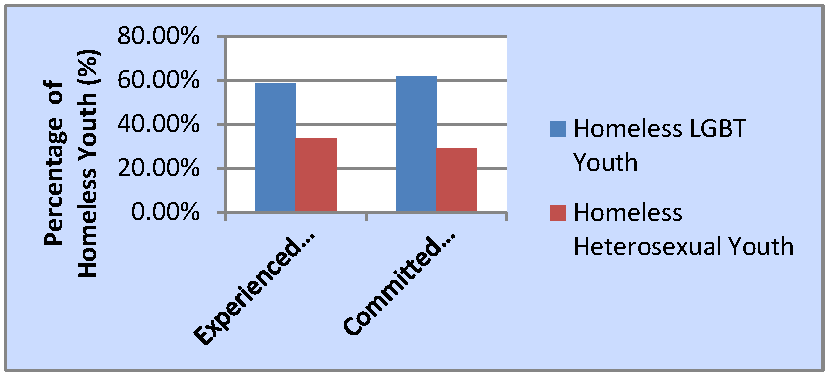

As of 2013, there were at least 1,868 homeless children living in DC; according to Advocates for Youth, 20-40 percent of these youth may identify as LGBT. Because the general youth population is only 10 percent LGBT, there is reason to believe that discrimination based on their sexual orientation is placing these youth at higher risk of experiencing homelessness. Once homeless, these youth experience significantly higher rates of sexual victimization than their heterosexual homeless youth counterparts, and are at much higher risk of self-violence.

To begin addressing the violence against LGBT-identifying youth in the DC area, we investigated successful strategies and proven best practices already in place in the community. Sasha Bruce Youthwork is a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the lives of runaway, homeless, abused, and neglected youth in DC. They serve 1,500 youth per year and provide basic needs as well as crisis intervention, case management, life skills training, and positive developmental activities (Sasha Bruce Youthwork, 2014). The DC Metro Gay Lesbian Liaison Unit is already established in NW DC and is responsible for the entire LGBT community. This unit also conducts campaigns on public safety and hate crimes to further educate the community. Through our research, we found their practices to be well established, accepted by the community, and successful in reaching LGBT-identifying youth.

Having established our problem as the gap between the LGBT-identifying youth most at risk for violence and the support and care services available to them, our intentions for our solution do not lie in creating new resources, but rather in bridging the gap between those LGBT youth experiencing homelessness who are at risk for violence and the resources already in existence to serve their needs.

To draw upon those already established resources, an ideal shelter must be selected, which satisfies a few key characteristics with the intent of enhancing their ability to serve those LGBT homeless youth that are most at risk for violence. The shelter should be of medium capacity with the ability to serve 150-200 youth. We have chosen to focus on the southeast DC location because it has the highest crime rates, meaning the LGBT youth experiencing homelessness in that area are the most at risk for violence. Naturally, we also need a shelter willing to work with us and the implementation of the policies and changes we recommend and will fund. The homeless shelter will be asked to hire a liaison for LGBT youth, who will coordinate ancillary care, such as mental health, case management, job training, and positive youth development activities.

Simultaneously, we will leverage the existing Gay and Lesbian Liaison Unit, or GLLU, of the MPD to establish a specific LGBT community liaison officer for youth. This position has the future capacity to be expanded to a team of liaison officers dedicated to supporting LGBT youth, which mirrors the established GLLU. The established liaison officer will assist and partner with the homeless shelter liaison and collaborate with local school counselors and school LGBT organizations in order to broaden our support system to include schools as well.

We will also enlist the support and help of the Center for Diversity and Inclusion at American University through their Safe Spaces Program, which aims to train and provide a network of students, staff, and faculty committed to supporting LGBT individuals and allies (AU, 2014). This program will be asked to partner with us to train the local police force in their best practices designed to resolve misconceptions surrounding the LGBT community and to promulgate a cultural familiarity with the LGBT community. Police are not only a vital link to the community; they are frequently involved in the crimes against LGBT youth and are sometimes the perpetrators of discrimination. Once trained, the police will not only act as conduits to other resources for LGBT youth, but they will join our support system in bridging the gap. Additionally, police are viewed as role models in the community. Therefore, by enlisting their support, we also hope to enlist the support of society members who look to them for guidance.

As the program at the homeless shelter grows, it will be increasingly important that the youth have a means to gain independence. One of the most important parts of their independence is to have a job. Because of this, we plan on partnering with local businesses to provide advanced job training and potential job opportunities. Local businesses have partnered with homeless shelters in the area before, and would likely be willing to partner with our shelter. Eventually, as the program develops, we intend to start up similar practices in other homeless shelters in the DC area using our pilot program.

We also intend to collect more data on LGBT-identifying youth using the Police Liaison Officer and LGBT Care Coordinator established at the homeless shelter as central points of contact. Having this ongoing information will help us alter the program according to what youth need. Reevaluating this information biannually in a joint conference involving all partners developed throughout the process will help to maintain an up-to-date picture on any new challenges LGBT youth in the area face.

We hope the downstream effects will serve in the future as a mechanism of primary prevention. This graphic, taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), depicts the framework and levels of interaction between the various components of our LGBT youth violence prevention and care program (CDC, 2014). The first level of our approach combats the homelessness experienced by LGBT-identifying youth, which currently increases their likelihood of becoming victims of violence. Next, we are establishing healthy and inclusive relationships for LGBT-identifying youth through mentorship and peer programs in the homeless shelter designed to reduce conflict and to make counseling and medical care available. Finally, the coalition established among the school system, police department, and homeless shelter work at the community level to foster a climate that promotes and supports healthy relationships, combating the aspects of the DC community that put LGBT-identifying youth at high risk for violence. In the future this framework can be used as a mechanism at the societal level to influence and create social and cultural norms that inhibit violence against LGBT-identifying youth.

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

Emily Bien, Yaroslav Daniel Bodnar, Jun Hu, Erin Mack, Brandon Shumway, Savannah Woodward

The proposed program on LGBT youth, named Insight, used a multifactorial, grassroots approach to decrease the incidence of violence against LGBT youth in DC. Many young people have limited insight into the impact of violence on LGBT individuals, as well as the effect of LGBT-targeted violence on the broader community. The Insight program applies proven school-based techniques, such as those used by Becoming A Man (B.A.M. Sports Edition, 2012) and No Bully (No Bully, 2013), and social media tools to guide DC-area high school students on an in-depth exploration of LGBT-targeted violence. By using gamification, Insight motivates students to actively engage in program activities. Insight activities provide students with self-directed, experiential learning that increases interpersonal understanding of LGBT-directed violence, in which they work as part of a diverse team on a creative project with the mentorship of a community leader. To translate student participants’ increased interpersonal understanding into positive behavior change, Insight focuses on peer reinforcement through teamwork, community engagement, school-wide support, and creation of social media content.

By facilitating a shared understanding of LGBT-targeted violence and promoting community accountability, Insight aims to give students the sense of justice necessary to resist and stop violence.

Engaging High School Students

The target population of the Insight program is DC youth in grades 9 to 12 because formation of gender identity peaks in high school and this period is when a significant proportion of gender-based violence occurs (Chestnut et al., 2013). According to the 2010 CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Kann et al., 2011), 5 percent of DC high school students identify as lesbian or gay, 7 percent as bisexual, 3 percent as questioning or unsure, and 1 percent as transgender. Compared to 9 percent of their heterosexual peers, 22 percent of lesbian and gay and 29 percent of bisexual DC high school students were harassed in 2009 (Kann et al., 2011). High school provides a convenient structure for effective implementation and evaluation of program interventions, especially because DC schools track data on violence and harassment.

The concept of gamification has been used successfully in marketing campaigns for decades (Van Grove, 2011; Toubia, 2006), but it is only recently becoming popular in educational applications. Insight motivates active engagement of students in program activities by providing recognition from their peers and community members, as well as rewards. Students will use social media to promote antiviolence messages. This helps to fulfill the dual purpose of engaging the participants by providing ownership of their content and marketing inspirational messages to bring attention to violence against LGBT people in the broader community.

Program Activities and Potential Partners

The Insight program is a team-based competition in which students of local high schools create multimedia proposals for a solution to violence against LGBT youth. Students voluntarily enter the competition either individually or as a team of up to three members. Under the guidance of the mentor, students will prepare and present their multimedia proposal to a stakeholder panel, which will include members of the LGBT community. Students of the participating schools will vote to select winning teams. The top three teams will work with media professionals to further develop their proposal into a public service announcement. The grand prize will be sponsorship of a community event, such as a dance or concert, so that all students from the winning school can celebrate their collective achievements.

To determine the impact of the Insight program on violence against LGBT youth, the competition will be implemented in three schools with three other controls. After obtaining baseline data on the incidence of LGBT-targeted violence in each school, data from these schools will be gathered for 4 years to evaluate the impact of the Insight program.

Potential Barriers and Responses

The most significant obstacle is obtaining buy-in from the entire community, particularly those that may not approve of engaging youth in LGBT topics, such as the Parent-Teacher Association and local religious leaders. By inviting voluntary participation, Insight reduces the controversy of addressing LGBT topics in a public school setting. Also, Insight will emphasize that violence and hate crimes against LGBT people affects everyone in the community. Other challenges for Insight may include low student participation and stability of future funding. Because keeping the program voluntary is important for its success, there is no guarantee that participation rates will reach the target of 30 percent. Finally, Insight was designed for sustainability, but depends on receiving financial sponsorships. Insight will maximize interest from donors by using social media to create excitement about the competition and by taking advantage of crowdsourcing platforms.

Sustainable Solution

Because the competition is hosted online, the Insight program can be scaled to include a larger number of schools. Effectiveness may improve with an increasing number of schools because greater participation increases peer reinforcement, enriches the online conversation, and draws greater attention to the issue. The Insight model can be reproduced anywhere that public schools are willing to partner sufficiently with the broader community. Because Insight is community-based, it conforms to the needs of the particular school, and can be transplanted anywhere. Lastly, although the Insight program is proposed as an intervention for LGBT-directed violence in DC, it provides a sustainable model for applying gamification to engage youth in an exploration of any public health issue. All of these factors combine to make Insight a promising intervention for LGBT-targeted violence in DC, as well as for sexual violence, drug and alcohol abuse, and other public health challenges anywhere in the United States.

Conclusion

Reflections

Student feedback post-competition was overwhelmingly positive, although a few students noted that prizes and other incentives for participating in the competition should have had higher stakes. Furthermore, although some students complained that only having 2 weeks to plan their responses caused stress and anxiety, this was an integral part of the challenge as it simulated working within time constraints and while under pressure.

Students particularly enjoyed the opportunity to engage in subject matter with which they were otherwise unfamiliar. They also noted that the case challenge provided a unique and interesting way of presenting material; several students mentioned that the competition design allowed them to digest the material while also engaging in their community. Many students contacted and worked with local organizations to gain a deeper understanding of the issues presented in the case, which met the project goals of fostering dialogue about the issues and linking a national organization and students from all over the United States to their local DC community.

Follow-Up Event

To further promote engagement of student participants in the case challenge subject matter and in its practical application within DC, the IOM convened a follow-up event to the competition. This event highlighted the work of the IOM’s Forum on Global Violence Prevention as well as local DC governing bodies and non-governmental organizations working on the repercussions of violence affecting LGBT-identifying youth. The event focused on two themes that arose from student solutions to the case challenge: anti-bullying efforts and counteracting homelessness in LGBT-identifying youth. It brought together DC-based non-profit organizations that work with area LGBT-identifying youth, DC public school officials and students, and DC Mayor’s Office officials. Representatives from the DCPS Office of Youth Engagement: Health and Wellness Team, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education, the DC Department of Human Services: Family Services Administration, the Latin American Youth Center, the Wanda Alston House, the DC Police Gay and Lesbian Liaison Unit, and the DC Mayor’s Office of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Affairs participated in a panel discussion of the topic.

We also invited two teams from the competition—one that proposed an anti-bullying social media campaign and one that focused on antihomelessness initiatives—to present their solutions to the panel of DC officials and field workers. The event served as an opportunity for DC policy makers, implementers, and students to exchange ideas on how to remedy facets of this important public health issue.

Future Plans

After a successful launch, the goal is to hold an annual case challenge. In 2014 the case challenge topic will be health and education, and will be carried out in partnership with the IOM Roundtable on Population Health Improvement.

References

- Advocates for Youth. 2013. Creating safe space for GLBTQ youth: A toolkit. Advocates for Youth: Rights, Respect, Responsibility. Available at: http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/publications/publications-a-z/608-

creating-safe-space-for-glbtq-youth-a-toolkit#tips (accessed November 6, 2013). - AU (American University). 2014. Safe space workshop. Available at: http://www.american.edu/ocl/cdi/SafeSpaceWorkshop.cfm (accessed November 4, 2013).

- Avenues for Homeless Youth. 2011. About Us. Available at: http://www.avenuesforyouth.org/ (accessed November 8, 2013).

- Cannon, K. D., and A. Dirks-Linhorst. 2006. How will they understand if we don’t teach them? The status of criminal justice education on gay and lesbian issues. Journal of Criminal Justice Education 17(2):262-278. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511250600866174

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2009. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/youth.htm (accessed November 5, 2013).

- CDC. 2014. The Social-Ecological Model: A framework for prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html (accessed November 9, 2013).

- Chestnut, S., E. Dixon, and C. Jindasurat. 2013. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and HIV-affected hate violence in 2012. Available at: http://www.avp.org/storage/documents/ncavp_2012_hvreport_final.pdf (accessed November 8, 2013)

- DC MPD. 2013. Annual FBI UCR crime totals by district 2008-2012. Available at: http://mpdc.dc.gov/page/annualfbi-ucr-crime-totals-district-2008-2012 (accessed November 1, 2013).

- DCPS (District of Columbia Public Schools). 2011. A plan to create an inclusive school community. Office of Youth Engagement. Washington, DC: DCPS, Office of Chief Academic Officer.

- DeJong, C., A. Proctor-Burgess, and L. Elis. 2008. Police officer perceptions of intimate partner violence: An analysis of observational data. Violence and Victims 23(6):683-696. Available at: https://ifls.osgoode.yorku.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/DeJong-et-al-2008-Police-Officer-perceptions-of-IPV-An-analysis-of-observational-data.pdf (accessed June 22, 2020).

- Durso, L., A. Kastanis, B. Wilson, and I. Meyer. 2013. Provider perspectives on the needs of gay and bisexual male and transgender youth of color. The Williams Institute, Los Angeles, CA. Avialable at: http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/safe-schools-and-youth/project-access-report-aug-2013/ (accessed November 4, 2013).

- Kann, L., E. O’Malley Olsen, T. McManus, S. Kinchen, D. Chyen, W. A. Harris, and H. Wechsler. 2011. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-risk behaviors among students in grades 9-12–youth risk behavior surveillance, selected sites, United States, 2001-2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 60. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. Available at: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED520413 (accessed November 7, 2013).

- Kärnä, A., M. Voeten, T. Little, E. Poskiparta, A. Kaljonen, and C. Salmivalli. 2011. A large-scale evaluation of the KiVa anti-bullying program; Grades 4-6. Child Development 82:311-330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01557.x

- No Bully. No Bully Evaluation Report for Lynx Foundation: 2012-13 Humboldt, Sonoma and Novato. 2013. Available at: http://www.nobully.org/sites/default/files/page/files/No%20Bully%20Evaluation%20Report%202012-

13%20from%20Moira%20Letterhead%20Deleted%20edited%20NC.pdf (accessed November 10, 2013). - Rigby, K. 2004. Addressing bullying in schools: Theoretical perspectives and their implications. School Psychology International 25(3);287-300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034304046902

- Roman, J., S. Bieler. 2013. District-wide model bullying prevention policy. Government of the District of Columbia, Washington, DC. Available at: http://ohr.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ohr/publication/attachments/DCBullyingPreventionPolicy_PressQ_022513.pdf (accessed November 4, 2013).

- Salmivalli, C., A. Kärnä, and E. Poskiparta, E. 2011. Counteracting bullying in Finland: The KiVa program and its effects on different forms of being bullied. International Journal of Behavioral Development 35:405-411. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025411407457

- Sasha Bruce Youthwork. 2014. History. Available at: http://sashabruce.org/about/ (accessed November 5, 2013).

- Sprigeo. 2013. The Story of Sprigeo. 2013. Available at: http://sprigeo.com/about-us/ (accessed November 8, 2013).

- Toubia, O. 2006. Idea generation, creativity, and incentives. Marketing Science 25(5):411-425. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1050.0166

- University of Chicago. 2012. B.A.M. – Sports Edition. Available at: https://crimelab.uchicago.edu/sites/crimelab.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/BAM_FINAL Research and Policy Brief_20120711.pdf (accessed November 5, 2013).

- Van Grove, J. 2011. Gamification: How competition is reinventing business, marketing & everyday life. Available at: http://mashable.com/2011/07/28/gamification/ (accessed April 26, 2014).

- Williford, A., B. Noland, T. Little, A. Kärnä, and C. Salmivalli. 2012 Effects of the KiVa anti-bullying program on adolescents’ perception of peers, depression, and anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 40(2):301-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9551-1

- HealthLeads. 2014. What we do. Available at: https://healthleadsusa.org/what-we-do/ (accessed November 8, 2013).

Diversity and Inclusion, Health Disparities, Health Equity, Population Health, Violence