How Much Do Healthy Communities Cost?

Today, most agree that achieving substantial improvements in population health and medical costs will require a greater focus on the upstream social determinants of health. I count myself among the converted, and I believe the community development sector’s work at the intersection of people and place offers many promising solutions. But we must ask ourselves what achieving impact at scale would look like, and what it would take to get there.

At a recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) roundtable workshop on resources for population health improvement, I was asked for an on-the-spot dollar estimate to provide full coverage for critical community development supports to help vulnerable children and families achieve better health and economic mobility. I quickly narrowed to two vital areas of upstream investment: housing and education, particularly early learning and child development programs. My organization, the Low Income Investment Fund, has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in these areas, leveraging private capital at a 7:1 ratio. For many years, research has linked both to a range of positive social outcomes—including improved health—and each is a critical platform for addressing health disparities.

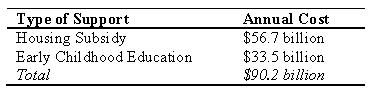

On stage at IOM, I did some quick math in my mind and leapt forward with an answer: “About $100 billion per year!” Let’s see how that hot-seat guesstimate stands up to the cold light of morning (and some serious analysis). The short answer is as follows: To serve 100 percent of poor families and kids in these two critical areas, the price tag is around $90 billion per year (see table below). Here is how I developed this estimate.

Affordable Housing. There are several ways to make rental housing affordable to poor families, but the most common and possibly cheapest way to do so is with rental assistance—such as with the federal Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, formerly known as Section 8.ii Under the HCV program, the government fills the cost gap between the rent that is affordable to a family and what a landlord charges for a unit on the open market. Meeting the need for affordable housing among the poor population could thus be quantified as what it would cost to provide rental assistance to all poor households who are “rent-burdened,” meaning they pay more than 30 percent of their incomes on rent. Only around one in four families who currently qualify for rental assistance get it, and often only after years of being on a waiting list.

Fortunately, the Bipartisan Housing Commission recently completed an analysis in support of its recommendation that the HCV program be “fully funded” for very low-income households making at or below 30 percent of area median income – a reasonable proxy for the poverty population. [iii] The cost to provide rental assistance to the approximately 6.3 million cost-burdened, poor renters in 2013 would have been $56.7 billion for the year, although the actual cost would likely have been much lower because participation would not be 100 percent.

Early Childhood Education. Similar to rental subsidies for affordable housing, federal funding for early childhood education falls far short of meeting existing need. As of 2013. only 4 percent of the eligible poor infants under age 3 who qualified for Early Head Start were able to access it, and Head Start was only funded to serve 41 percent of eligible poor 3- and 4-year-olds. [iv] Accounting for my estimate of the number of poor children served by the federal Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) program [v], the annual sot of expanding Early Head Start to cover all remaining poor children ages 3 and 4 would be $5.7 billion. [vi] These calculations are based on cost-per-slot data provided by the New America Foundation. And as with rental assistance, participation would not be 100 percent, so accounting for actual participation rates would lower cost estimates.

Conclusion. Although my original back-of-the-envelope estimate of $100 billion per year seemed large, a reasonable analysis bears it out at an order of magnitude of accuracy. And while these upfront costs are significant, solid research suggests even greater short- and long-term cost savings to taxpayers from these social interventions. Estimates from random assignment experiments suggest an annual rate of return between 7 and 10 percent for early childhood education, and there is a wealth of research demonstrating the central role that affordable housing plays in children’s educational performance, health, and long-term economic prospects. Housing-based interventions can also pay shorter-term dividends for adults in areas such as diabetes and obesity. [vii] Finally, it is worth noting that public-private partnerships could leverage that $100 billion per year in public subsidy into even larger investments. Achieving impact at this scale would provide a significant boost to the future economic and social fabric of our country and would be a smart population health strategy.

References

i. A workshop summary is available for free download at www.iom.edu/financingpophealth.

ii. The other most common way is to provide subsidies for the construction of housing that is required to remain affordable to low-income households in exchange for government support. Today, the HCV program supports more families.

iii. For the full recommendations and report, see: Bipartisan Policy Center, Economic Policy Program, Housing Commission. 2013. “Housing America’s Future: New Directions for National Policy.” February. http://bipartisanpolicy.org/sites/default/files/BPC_Housing%20Report_web_0.pdf (accessed December 2, 2014).

iv. U.S. Census. 2013 Current Population Survey. http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/cpstables/032014/pov/pov34_100.htm (accessed December 2, 2014).

v. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Child Care. Characteristics of Families Served by Child Care and Development Fund (CCDC) Based on Preliminary FY 2012 Data. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/occ/resource/characteristics-of-families-served-by-child-care-and-development-fund-ccdf (accessed December 2, 2014.)

vi. See http://febp.newamerica.net/backgroundanalysis/head-start (accessed December 2, 2014). These calculations also do not account for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families dollars spent directly on child care, nor does it account for the range of state and local subsidies for child care that serve poor children. Accounting for these additional funding streams is complicated and difficult, but doing so would lower any calculation of a funding gap to serve poor children four years old and younger. vii Ludwig, et al. 2011. Neighborhoods, Obesity, and Diabetes—A Randomized Social Experiment. New England Journal of Medicine 365:1509-1519. October 20.