A Measurement Framework for Early Childhood: Birth to 8 Years of Age

In recent years, mounting evidence on the importance of early childhood development has led to growing attention to children’s experiences from birth to 8 years of age. In addition to spurring the development of new models to directly support young children and their caregivers, there has also been an increased emphasis on national policies and practices integral to protecting young children’s rights. Yet despite increased attention, millions of young children are still not experiencing the conditions necessary to support their development. Concerted and coordinated action is required, on behalf of young children, to build the infrastructure necessary to ensure that all young children experience the conditions needed to reach their developmental potential. An essential component of this infrastructure is the ability to measure results for children.

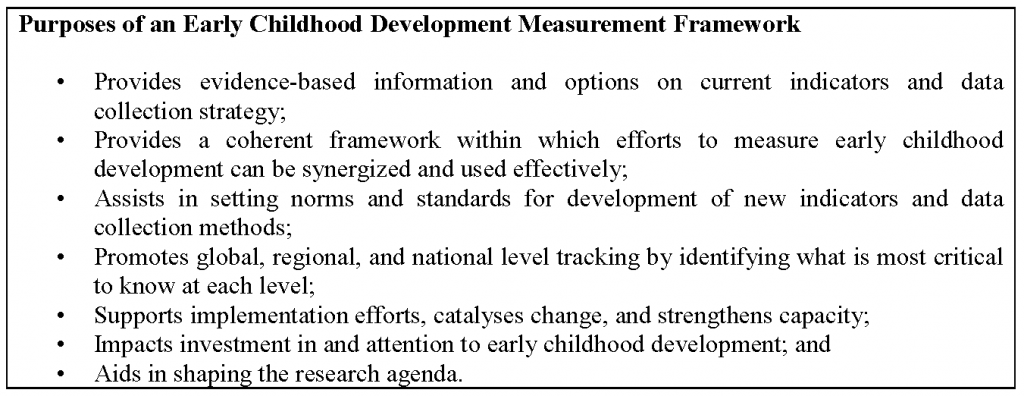

The recognition of a lack of indicators to measure early childhood development has led to the proliferation of multiple initiatives and approaches at global, regional, and national levels (see section 3 for details). These approaches are at differing stages of development and implementation. Although the promise of these approaches is yet to be actualized, currently they are uncoordinated. The lack of coherence may lead to duplication of efforts, inefficient use of resources, and potentially diffused results. Therefore, at this stage it will be beneficial to create a coordinated and harmonized measurement framework.

Measurement frameworks include standards, indicators, measurement tools, and assessment guidance. Measurement frameworks have been able to guide coordinated action in countries, regions, and at the global level, because they provide a platform for stated agreements on what is most critical to measure; clarify the purposes for measurement; spur the creation, adaptation, and adoption of measurement tools that can be used to improve services for children; and finally, encourage regular collection of indicators to track progress. Measurement benefits from efficiencies of scale: By aligning efforts, better and more complete data are obtained, and innovations are shared more rapidly.

We focus on the conceptualization of the measurement framework and the need for harmonization of work across multiple agencies and organizations to better track results for children. This paper is organized into four sections:

- Why is it important to measure early childhood development?

- How can child rights and science be integrated into one measurement framework?

- What is currently available to measure early childhood development?

- What should be the core principles that underlie a measurement framework?

We conclude with a vision for such a measurement framework and its function and role in promoting the development of all children.

1. Why Is It Important to Measure Early Childhood Development?

Measurement plays an important role in facilitating action on behalf of young children. A common set of reliable, accurate, and regularly collected indicators that reflect the most critical elements of young children’s environments and well-being can inform action by providing programs, national governments, and multinational organizations with data to assess progress and guide decision making. Measurement is important because it can lead to changes in the experiences of young children by influencing global priorities and funding; national policies and programs; and the interactions children experience with parents, teachers, and other caregivers.

Designing effective measurement systems to measure and track progress in early childhood development is becoming increasingly important. At the national level, there has recently been an increase in the number of countries identifying investments in young children as an economic and social sector growth strategy. According to data collected by UNICEF, in 2013, 61 percent of UNICEF’s Country Offices reported that National Development Plans (or equivalent) include targets for scaling up improved family and community care practices for mothers and children. This number has almost doubled from 32 percent in 2005. Although the commitment to investing in and supporting early childhood development is promising, it is also important to note that much of the evidence on the effectiveness of programs to support early childhood development has been generated from demonstration projects, which are now ready to be taken to scale within countries or regions. Successful “scaling up” of demonstrations needs to be accompanied by monitoring and measurement that allow for both analyses and evaluation of the implementation and results. This will require a strong measurement framework and tools to monitor investments and progress.

Coinciding with the need for reliable and accurate data to inform scaling and program investments at the national level, early childhood development is gaining global recognition. The emerging frameworks for post-2015 sustainable development have started to include early childhood development. The Open Working Group outcome document and the Sustainable Development Solutions Network Framework both include a target for early childhood development (United Nations General Assembly, 2014; Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2014). Given this inclusion of early childhood development as a target, there is an urgent need to develop a measurement framework that will allow for ongoing tracking and monitoring of progress on national, regional, and global levels.

Alongside national and global demand, there has been considerable progress in measuring various domains of early childhood development. For example, we are now better able to measure social development, executive function, and allied skills that are linked to healthy development and well-being. However, at present, the information collected across key domains of early childhood development, though useful, is ad hoc. There is some degree of coordination and coverage of important areas of early childhood development and impressive work in some regions of the world, but many important indicators have not yet been developed or are collected inconsistently (LMTF, 2014).

2. How Can Child Rights and Science Be Integrated Into One Measurement Framework?

Twenty-five years ago, the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child articulated a global agreement that children have the right to experience environments that are safe and nurturing in the short term and promote their ability to achieve their developmental potential over the life course. The framework proposed by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child addressed the following themes: the need to recognize young children as rights holders and active social participants; duty bearers’ obligations to provide appropriate and adequate support to caregivers of young children; the need for integrated service provision in support of holistic approaches to child development; the need to support young children’s evolving capacities, through empowering and positive education, preschool, and play experiences; freedom from social exclusion by virtue of young age, gender, race, disability etc.; freedom from violence; and understanding of the particular vulnerability of young children.

Although not consistently collected at the global level, the child rights framework has been translated into proposed indicators to track progress toward fulfilling young children’s rights, including children’s access to safe, stimulating environments; health care; adequate nutrition; and protection of basic rights.

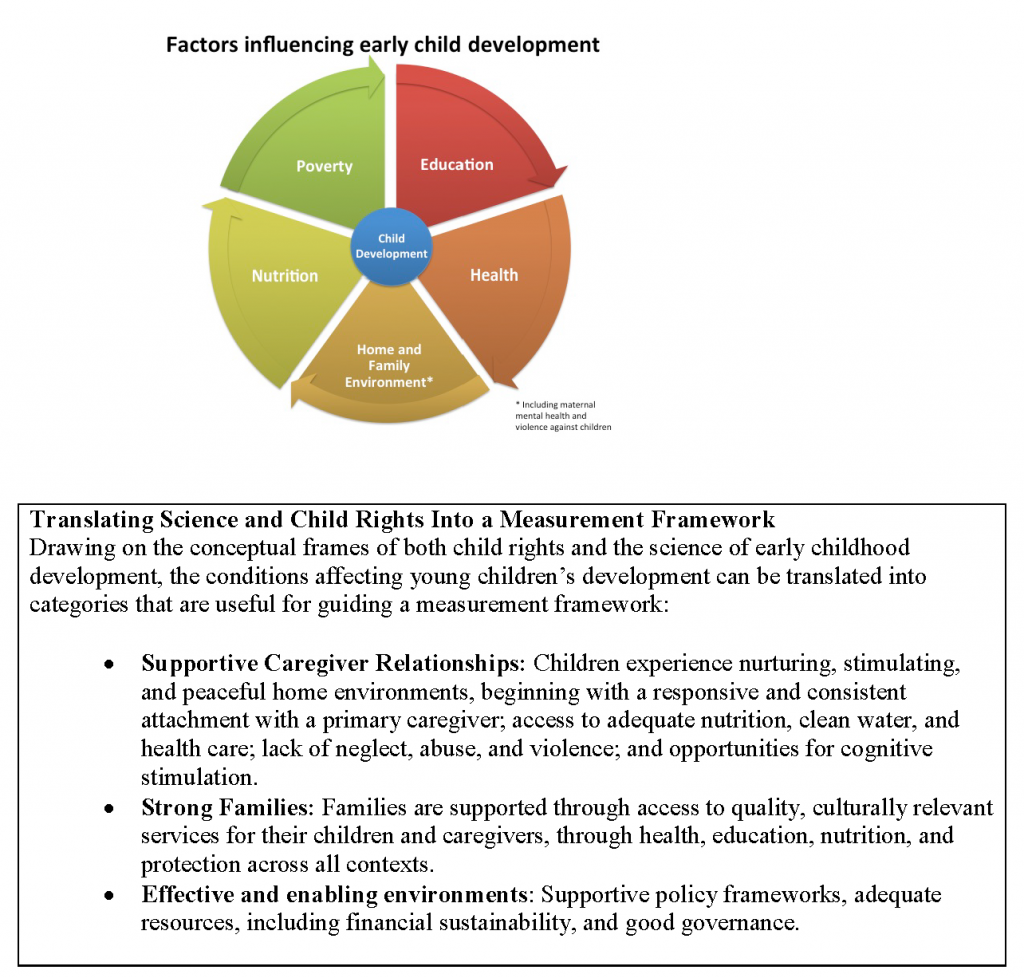

There is considerable agreement between science and child rights experts on what is most critical for young children’s development. From a biopsychosocial perspective, the ecological model enshrined in a child rights framework resonates with the science indicating the important influence of the environment on early development. Furthermore, the rights and scientific frameworks align on the layering of the environment, stressing the direct influence of proximal environments and mediated influence of more distal, macro contexts. Early childhood development is typically characterized by scientists as a process of growth and change over the period from birth to age 8, resulting from interactions among biological, cultural, and societal factors. Research has demonstrated the importance of these dynamic interactions on children’s development, through genetic predisposition (including the extent to which experiences can influence gene expression); nutrition (including the consequences of both inadequate and excessive food intake); environmental influences (including exposure to toxic chemicals); and social experiences (including the effects of poverty, population displacement, unstable relationships, and exposure to violence) (Shonkoff, et al., 2012). Rapid development of the brain and our biology occurs during the early years, setting children on trajectories toward health and well-being that persist throughout the life course. What happens in first years of life lasts a lifetime, including implications for societies (Britto, et al., 2013).

Therefore, a measurement framework must take into account the following:

- The rapid pace and complexity of early childhood development, by collecting information at multiple points in young children’s lives, from birth through age 8, and focusing on the environment as well as the child’s characteristics;

- All domains of development, including language, physical, socio-emotional, and cognitive development;

- Multiple factors that make up children’s environments, from experiences within children’s homes, including nutrition, parenting, and exposure to violence; the availability and quality of programs that aim to support early childhood development; and the policies and laws that influence child development and protection of children’s rights;

- A focus on equity, by measuring factors associated with inequity and examining their relationships to access to and participation in services and desired outcomes.

3. What Is Currently Available to Measure Early Childhood Development?

Considerable progress has been made toward defining and measuring many areas of early childhood development:

- Global Level: There are several notable advances in collecting globally comparable data on early childhood. First, with a focus on low-resource countries, UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) provides the world’s most comprehensive source of global data on early childhood development including indicators on children birth through age 5, but also indicators on youth and adolescents. MICS includes indicators of child development and well-being, parenting, and children’s access to services across a range of areas, including health, nutrition, and education. The first global monitoring of early childhood development resulted from the creation of the MICS–Early Childhood Development Index. This 10-item module assesses the development of children aged 3 to 5 years as part of the MICS household survey and now has been collected in more than 60 countries (http://data.unicef.org/ecd/overview).

- Regional Level: Several measures of early childhood development and learning in particular have also been developed for use across regions or globally, demonstrating that it is possible to develop approaches to measurement that are relevant across contexts. In West and Central Africa, three prototypes have been developed to measure child outcomes, quality of caregiving, and the cost of early childhood development program implementation. These prototypes highlight the necessity of understanding optimal conditions in low-resource settings. In East Asia and the Pacific regions, a scale of child learning and development is being finalized that presents an index to measure what children should learn and be able to do at specific ages during the early childhood period with relevance for the region. Given the forward progress, the next step is to harmonize efforts to learn from what has been developed and identify pathways forward toward more comprehensive data collection.

- National Level: National data on early childhood development are available in some countries. A recent analysis using data from the World Bank’s Systems Approach for Better Education Results Early Childhood Development Framework (SABER-ECD) and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) indicates that at present, few countries consistently measure child development and learning at the population level, but rather, more are investing in national measures of early childhood development in particular, with some countries also focusing on family environments or quality of learning environments. A recent initiative led by UNESCO, UNICEF, the World Bank, and the Brookings Institution aims to assist countries in reliable, consistent measurement of children’s development and quality of learning environments at the national level.

Data to inform tracking at all levels are primarily generated from household surveys or are administrative data collected by national ministries of education and/or health. Information on national, regional, or global trends in policies and laws relevant to early childhood development typically requires review by outside parties, such as the World Bank’s SABER-ECD. Recent advances in mobile technology have also facilitated fast-forward motion in oral assessments of learning, which rely on household surveys but ensure fast, accurate reporting of data. Each data collection method has strengths and disadvantages. Administrative data, which come from government collection and reporting of ongoing data, are more deeply integrated into government reporting and therefore may be more relevant to policymakers but are dependent on the quality and accuracy of national ministries and statistical offices. Household surveys offer more opportunities to collect widespread data on individuals, which are important for tracking inequities and for obtaining reliable information on individuals who may not be regularly included in government systems, but which are more expensive and time-intensive to collect, and therefore may not be collected as frequently.

Despite the forward momentum on measuring early childhood development, several areas need further attention. First, the tools used to measure child development, including the ages at which children’s development is assessed, the methods used, and the range of behaviors included, must be carefully considered. Development emerges from the individual child’s interaction with the environment, which manifests in observable behavior by the child. While children at younger ages exhibit a more limited repertoire of behavior, even the simplest behaviors describe a complex array of developments. For example, babbling for an infant is an indication of progress in several developmental domains, such as language, social interaction, and emotional expression. Although children’s development progresses in trajectories from early in infancy onward, the process of skill mastery in the early years means that very young children’s behavior can be inconsistently related to later development, as they are still mastering skills. Especially when results from assessments are used to inform policies and tracking toward goals, the validity and reliability of the measures should be carefully considered, and multiple observations at different ages might be required for accurate estimates. These issues, among others, must be addressed as part of a measurement framework.

Second, across all data collection methods, the quality of the data depends on the strength of the statistical system in collecting and reporting on data. Finding the right combination of data collection strategies is essential for creating a feasible, accurate system of measurement. Third, a greater understanding of how the data are used for improvement is needed. Finally, several important indicators, notably children’s developmental status prior to the preschool years, the number of children with special needs, and the quality of children’s learning environments in the preschool and early school years are not available on a global level and vary in availability at the regional and national levels. An investment in measurement is needed to develop the new indicators required to achieve a holistic viewpoint of early childhood development; to build the infrastructure required to ensure accurate and reliable data collection; and in particular, to help identify innovations and approaches to using data for improvement.

4. What Should Be the Core Principles That Undergird the Measurement Framework?

Reflecting on the experiences gained from the strong technical work completed to date and noting the new demands for early childhood data, it is clear that more data alone will not necessarily encourage action on the part of children. Instead, we envision a framework that focuses on tracking implementation within systems that support early childhood development and identifying from the start how data can be used for improvement at all levels, from the national to the global.

i. Measurement should encourage emphasis on inputs and outputs, as well as child outcomes. To track progress in early childhood development, children’s development and learning must be tracked in partnership with measurement of the functioning of programs, services, and government support for young children and families. Using measurement to support implementation of quality, accessible services for young children is a primary goal. This will require measuring multiple layers of the systems that support early childhood development, including contextual factors, inputs (policies and laws); outputs or coverage of interventions, services, and programs; and impact on child development outcomes (see Figure).

ii. Measurement should encourage a focus on improvement in children’s experiences and outcomes. With recent advances in technology, the ability to use data for direct and immediate improvement in children’s environments and experiences has never been greater. Focusing on the purpose of data collection, and in particular, the role of data in ensuring quality services and supportive environments for children, can help prioritize and increase the value of measurement. National governments, for example, may require different data than global organizations; such clarifications in purpose should be addressed so that solutions for effective data use can be generated.

iii. Measurement requires articulation of the roles of measurement at the national, regional, and global levels. Global tracking requires comparable data across countries, while national tracking can more closely reflect national priorities and values for young children and may also be more relevant for tracking access to quality programs. When measuring across contexts, it is important to build indicators that reflect both the patterns and commonalities in young children’s development as well as the influence of contextual factors, as young children’s development is contextually sensitive and indicators do not always have the same meaning in different contexts. Global data, which require a common definition and approach to data collection across countries, may be more relevant and useful in tracking some areas of early childhood development than others.

To effectively promote early child development within a measurement framework, the availability of high-quality data is essential. Improvement in the global collection of quality data on early childhood indicators, cross-sectoral collaboration in developing and implementing effective strategies and plans, and increased public- and private-sector investment are all needed to ensure that children survive and thrive. Many organizations have interest and expertise in further developing indicators, which will be greatly facilitated by coordinated efforts that allow testing of items and comparison of results across settings. By creating a birth-to-8 measurement network or platform, bringing together all interested stakeholders, it will be possible to harness resources efficiently and meet the goal of a holistic implementation and assessment approach to child health and development.

A Vision for an Early Childhood Measurement Framework

Early childhood development is increasingly recognized as one of the most important investments in individual and sustainable development. Measurement must evolve to provide reliable and valid information on whether the desired inputs, outputs, and outcomes of investments in early childhood development are being achieved. In response, UNESCO, UNICEF and WHO have joined forces to develop a shared measurement framework that cuts across sectors and can efficiently prioritize, validate, and report on new indicators and measurement systems for early childhood development. In undertaking this work, we aim to build on the substantial efforts to date, while also looking to innovations in other sectors; reliance on technology; and perhaps most critically, a focus on how the data can be used to promote change. It is unlikely that a full set of early childhood development indicators will be available in the near future, especially as some of the more complex topics, such as quality of early childhood development services, are still in the process of being fully defined. Therefore, it may be important for the early childhood development community to prioritize which indicators it sees as most critical to collect, and how the data can best be used for improving early childhood development processes and outcomes. To fulfill these goals, a task team is needed to provide a forum for discussion and agreement to facilitate effective action in the measurement of early childhood development.

References

- Britto, P. R., P. L.Engle, and C. S. Super. 2013. Handbook of early child development research and its impact on global policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- LMTF (Learning Metrics Task Force). 2014. Toward universal learning: Implementing assessment to improve learning. Report No. 3 of the Learning Metrics Task Force. Montreal and Washington, D. C.: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), and Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution.

- Shonkoff, J. P., L. Richter, J. van der Gaag, and Z. A. Bhutta. 2012. An integrated scientific framework for child survival and early childhood development. Pediatrics 1129:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0366

- Sustainable Development Solutions Network. 2014. Indicators and a monitoring framework for sustainable development goals. Available at: http://unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/140724-Indicator-working-draft1.pdf (accessed October 25, 2014).

- United Nations General Assembly. 2014. Report of the Open Working Group of the General Assembly on Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/68/970 (accessed October 25, 2014).