The Business Role in Improving Health: Beyond Social Responsibility

Introduction

Although there is growing understanding that fundamental population health improvement will require multisectoral partnerships (Posner, 2010), the specific role of employers in such partnerships has been less well explored. While corporate social responsibility plays an important motivational role, more traction will be possible if improving health can be linked to corporate bottom-line performance. This paper explores why business should engage in improving population health.

Themes

Corporate Business Goals and Community Health

Improving the health of the community where a company is located can contribute to achieving corporate business goals. The involvement of business with health care and public health is often focused on reducing health care costs and improving employee productivity (Baicker et al, 2010). As important as these are, we believe that current understanding of the many factors that contribute to better health provide a rationale for an even wider role for businesses in making surrounding communities healthier. This role can be rooted in core business objectives far beyond corporate social responsibility. According to Andrew Webber, President and CEO of the National Business Coalition on Health, “Business leaders must understand that an employer can do everything right to influence the health and productivity of its workforce at the worksite, but if that same workforce lives in unhealthy communities, employer investments can be seriously compromised” (Webber and Mercure, 2010).

Determinants of Population Health

Improving population health requires much more than high-quality, affordable health care. Health outcomes in the United States lag behind those in most developed countries by a wide margin, despite the fact that the United States spends substantially more on health care than its peers (IOM and NRC, 2013). Within the United States, we continue to experience substantial disparities by race, income, and geography, and, as shown in a recent report, there has been absolute worsening in mortality rates in many U.S. counties over the last decade (Kindig and Cheng, 2013).

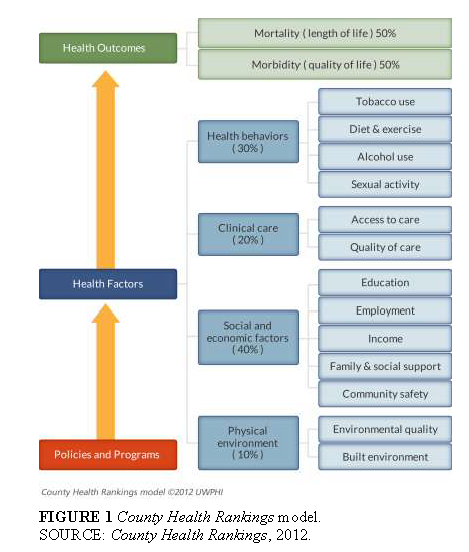

As important as health care quality and access is, the last several decades have shown that health outcomes are the product of many factors beyond health care. The widely used County Health Rankings (County Health Rankings is a collaboration of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin.) weight the multiple factors as 20 percent for health care, 30 percent for health behaviors, 40 percent for social factors like education and income, and 10 percent for the physical environment (see Figure 1).

The Critical Role of Business

We believe that the business sector plays a critical role in many determinants of health. While the health care system has primary responsibility for health care quality and access and, to some extent, for health behaviors, it has more limited roles in the social and physical environments. The business sector usually strives to maximize the value of health care dollars invested in the workforce because lower costs or better outcomes generally translate to a healthier and more productive workforce and a more successful enterprise. Business can also influence health care through purchasing requirements. Such requirements can specify the health care product they are purchasing and mandate that health care providers must practice evidence-based medicine. The focus is primarily on controlling the cost of services provided to employees and their dependents while ensuring an acceptable level of quality. Some larger employers also directly provide employee health services. Health care benefit design impacts both health care costs and employee recruitment and retention.

The business case for focusing on health behaviors has been to foster employee wellness, which is seen as improving productivity in the short run and reducing health care costs in the long run. With respect to social and economic factors, the strongest business contribution may be in employment itself, both in the employment-to-population ratio and the contribution to individual and family income. There is also growing realization by employers that K-12 and early childhood education programs in their communities contribute to business profitability in the short and long runs. In terms of the physical environment, some industries have substantial responsibility in areas of air and water quality and in community land use planning. There also has been a growing interest in the environmental factors that contribute to obesity in communities, for example, lack of opportunities for physical activity or for purchasing healthy food.

Impact of Community Health on Business Objectives

Improving the health of communities and individuals is important to core business objectives. While corporate social responsibility must be valued and encouraged, we believe the role of business in communities’ health improvement efforts will be limited in impact and sustainability if not tied to bottom-line performance.

Better community health can contribute to the bottom line in many ways beyond reducing health care costs. Cathy Baase, Dow Chemical’s Global Director of Health Services, has identified the following benefits of business involvement: attracting and retaining talent, employee engagement, human performance, personal safety, manufacturing and service reliability, sustainability, and brand reputation.

Also important is the link between employee well-being and profitability. One large retailer regularly assesses employee well-being and compares these data with sales and profitability figures.

The business community understands the health care and education connection. The poor health of our children will lead to rising health care costs, which will then exhaust the resources for education. One approach to long-term investments in youth development is through mentoring relationships. For example, one company recruits youth (from as early as the first grade) who might otherwise end up on the street or in jail to participate in supportive relationships and then guarantees jobs as long as the students earn good grades. The business case for investing in education in the community is that the company needs employees.

Social responsibility commitments of businesses can often lead to enhanced company reputation and customer loyalty. When a business reflects customers’ values (such as making a strong financial commitment to education), people feel good when they walk in, and it improves the brand.

Business Roles in Health Improvement Vary

Large employers with stable, older workforces may see greater bottom-line return than employers with younger, high-turnover workforces. Smaller employers will be limited in what they can do alone but could operate through employer coalitions or Chambers of Commerce.

Multisectoral Partnerships

No single sector is solely responsible for health improvement. Businesses can lead or play strong supporting roles in community multisectoral partnerships. It follows from a multideterminant understanding of health that no one organization or sector is totally responsible for improving health outcomes. For the business sector, the relationship of core corporate objectives to each of the determinant areas is different than for the health care sector, since businesses have less control over what is necessary to improve health. Real and meaningful improvement will require active participation and resources from multiple sectors of society, including health care, public health, schools, businesses, foundations, and government at all levels.

We believe that meaningful improvement requires collective action by sectors not used to working together. Many sectors do not understand how activities in their sector are important to and impact the overall goal of improving health. In some communities, because of their prestige, political clout, and financial resources, businesses can be the super integrator (Kindig, 2010) across the stakeholders. Businesses must partner with others to achieve health improvement in communities and thereby reap the advantages for their workforces and overall well-being of business activity. Michael Porter observed that the “solution lies in the principle of shared value, which involves creating economic value in a way that also creates value for society by addressing its needs and challenges. Businesses must reconnect company success with social progress” (Porter and Kramer, 2011).

Steps to Action

What steps need to be taken to assist businesses to take a more active role in community health improvement? How do we get to that future from where we are today? What are the gaps and the barriers? We have identified seven activities that could advance understanding and action in this area.

- Set galvanizing goal targets. Most business leaders understand the concept of impact metrics and know how they can drive strategic investments.

- Extend a meaningful invitation from those currently engaged in improving population health to business regarding their views, needs, and involvement. There is no shared understanding of who “owns” the health improvement space in communities. In some sense, the community health improvement “sandbox” still seems largely controlled by health care and public health, with business sector participation limited due to fear of meddling, revenue loss, or disruption of an ecosystem configured to maximize success for a designated few.

- Engage in education efforts for CEOs and others in the C-Suite. One useful tool might be a population health primer from a business perspective or an action kit for business involvement. Such efforts would need to be built into existing channels of information for businesses, such as a Conference Board or Business Roundtable. To be successful, business-sector engagement must address issues beyond health care costs.

- Sponsor convenings with broader community partners. It is important to engage community partners but were much less certain about how to do so is not certain. One approach might be to create a chartered value exchange to foster multi-stakeholder dialogue and convene around health for employers, health providers, public health organizations, and consumers

- Develop and widely share case studies of businesses that are already making progress in community health improvement activity.

- Promote “Triple Aim” collaboration with business. The Triple Aim is a policy framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. It advocates the simultaneous improvement of patient experiences of care (including quality and satisfaction), reduction in per capita health care costs, and improvement of population health. Although most Triple Aim sites define their populations by the service areas of health care delivery systems, several initiatives have adopted a regional approach and are defining their populations geographically (Kindig and Whittington, 2011). Business-sector partners could benefit greatly from recognizing the value of Triple Aim goals and engaging in collaborative efforts to achieve them.

- Identify permanent revenue streams for carrying out these activities. In addition to corporate contributions, businesses can partner with others in obtaining foundation or government grants for activities. In addition, many experts argue that as much as 25 percent of current health care spending is ineffective, improving neither outcomes nor quality. Capturing these dollars for reinvestment in more effective programs and policies within and outside of health care will not be easy, but nevertheless should be a high priority for both public- and private-sector leaders. Consideration should be given to setting aside a community share from savings anticipated under the implementation of accountable care organizations, which are designed to provide higher-quality care in a more efficient manner (Magnan et al., 2012). Also, as uncompensated care burdens are reduced under health reform, community benefit resources required by the Internal Revenue Service for nonprofit tax-exempt status could be redirected from charity care into broader health-promoting investments (Bakken and Kindig, 2012). This is a considerable sum; as of 2002, the most recent year examined, the national value of this tax exemption was $12.2 billion (U.S. Congressional Budget Office, 2012).

Conclusion

The authors believe that there is a solid argument to be made for a much stronger role for businesses in population health improvement. Such improvement can enhance corporate core objectives beyond those of social responsibility. It is hoped that the ideas presented here will contribute to a more robust discussion of this potential and lead to action at all levels, from individual communities to the nation as a whole.

References

- Baicker, K., D. Cutler, and Z. Song. 2010. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Affairs 29(2):304-311. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626

- Bakken, E., and D. A. Kindig. 2012. Is community benefit charity care? Wisconsin Medical Journal 111(5):215-219. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23189454/ (accessed May 22, 2020).

- U.S. Congressional Budget Office. 2006. Non-profit hospitals and the provision of community benefits. http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/76xx/doc7695/12-06-nonprofit.pdf (accessed September 5, 2012).

- County Health Rankings. 2012. County health rankings model. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/resources/county-health-rankings-model (accessed July 2, 2013).

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2013. U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13497

- Kindig, D. A. 2010. Do we need a population health super-integrator? Improving Population Health. Available at: http://www.improvingpopulationhealth.org/blog/2010/09/super_integrator.html (accessed May 22, 2020).

- Kindig, D. A., and J. Whittington. 2011. Triple Aim: Accelerating and sustaining collective regional action. Improving Population Health. Available at: http://www.improvingpopulationhealth.org/blog/2011/11/triple-aim-accelerating-and-sustaining-collective-regional-action.html (accessed May 22, 2020).

- Kindig, D., and E. Cheng. 2013. Even as mortality fell in most US counties, female mortality nevertheless rose in 42.8 percent of counties from 1992 to 2006. Health Affairs 32(3):451-458. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0892

- Magnan, S., E. Fisher, D. Kindig, G. Isham, D. Wood, M. Eustis, C. Backstrom, and S. Leitz. 2012. Achieving accountability for health and health care. Minnesota Medicine 97(11):37-39. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23243752/ (accessed May 22, 2020).

- Porter, M., and M. Kramer. 2011. The big idea: Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review 89(1-2):1-17. Available at: https://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creating-shared-value (accessed May 22, 2020).

- Posner, S. 2010. Mobilizing Action Toward Community Health (MATCH) special issue on partnerships. Preventing Chronic Disease 7(6). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/nov/toc.htm (accessed May 22, 2020).

- Webber, A., and S. Mercure. 2010. Improving population health: The business community imperative. Preventing Chronic Disease 7(6):A121. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/nov/10_0086.htm (accessed May 22, 2020).