Core Principles & Values of Effective Team-Based Health Care

Goal

This paper is the product of individuals who worked to identify basic principles and expectations for the coordinated contributions of various participants in the care process. It is intended to provide common reference points to guide coordinated collaboration among health professionals, patients, and families—ultimately helping to accelerate interprofessional team-based care. The authors are participants drawn from the Best Practices Innovation Collaborative of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care. The Collaborative is inclusive—without walls—and its participants are drawn from professional organizations representing clinicians on the front lines of health care delivery; members of government agencies that are either actively involved in patient care or with programs and policies centrally concerned with the identification and application of best clinical services; and others involved in the evolution of the health care workforce and the health professions.

Teams in health care take many forms, for example, there are disaster response teams; teams that perform emergency operations; hospital teams caring for acutely ill patients; teams that care for people at home; office-based care teams; geographically disparate teams that care for ambulatory patients; teams limited to one clinician and patient; and teams that include the patient and loved ones, as well as a number of supporting health professionals. Teams in health care can therefore be large or small, centralized or dispersed, virtual or face-to-face—while their tasks can be focused and brief or broad and lengthy. This extreme heterogeneity in tasks, patient types, and settings is a challenge to defining optimal team-based health care, including specific guidance on the best structure and functions for teams. Still, regardless of their specific tasks, patients, and settings, effective teams throughout health care are guided by basic principles that can be measured, compared, learned, and replicated. This paper identifies and describes a set of core principles, the purpose of which is to help enable health professionals, researchers, policy makers, administrators, and patients to achieve appropriate, high-value team-based health care.

The Evolution of Teams in Health Care

Health care has not always been recognized as a team sport, as we have recently come to think of it. In the “good old days,” people were cared for by one all-knowing doctor who lived in the community, visited the home, and was available to attend to needs at any time of day or night. If nursing care was needed, it was often provided by family members, or in the case of a family of means, by a private-duty nurse who “lived in.” Although this conveyed elements of teamwork, health care has changed enormously since then and the pace has quickened even more dramatically in the past 20 years. The rapidity of change will continue to accelerate as both clinicians and patients integrate new technologies into their management of wellness, illness, and complicated aging. The clinician operating in isolation is now seen as undesirable in health care—a lone ranger, a cowboy, an individual who works long and hard to provide the care needed, but whose dependence on solitary resources and perspective may put the patient at risk. [1,2]

A driving force behind health care practitioners’ transition from being soloists to members of an orchestra is the complexity of modern health care, which is evolving at a breakneck pace. The U.S. National Guideline Clearinghouse now lists over 2,700 clinical practice guidelines, and, each year, the results of more than 25,000 new clinical trials are published. [3] No single person can absorb and use all this information. In order to benefit from the detailed information and specific knowledge needed for his or her health care, the typical Medicare beneficiary visits two primary care clinicians and five specialists per year, as well as providers of diagnostic, pharmacy, and other services. [4] This figure is several times larger for people with multiple chronic conditions. [5] The implication of these dynamics is enormous. By one estimate, primary care physicians caring for Medicare patients are linked in the care of their patients to, on average, 229 other physicians yearly, [6] to say nothing of the vital relationships between physicians, nurses, physician assistants, advanced practice nurses, pharmacists, social workers, dieticians, technicians, administrators, and many more members of the team. With the geometric rise in complexity in health care, which shows no signs of reversal, the number of connections among health care providers and patients will likely continue to increase and become more complicated. Data already suggest that referrals from primary care providers to specialists rose dramatically from 1999 to 2009. [7]

Given this complexity of information and interpersonal connections, it is not only difficult for one clinician to provide care in isolation but also potentially harmful. As multiple clinicians provide care to the same patient or family, clinicians become a team—a group working with at least one common aim: the best possible care—whether or not they acknowledge this fact. Each clinician relies upon information and action from other members of the team. Yet, without explicit acknowledgment and purposeful cultivation of the team, systematic inefficiencies and errors cannot be addressed and prevented. Now, more than ever, there is an obligation to strive for perfection in the science and practice of interprofessional team-based health care.

Urgent Need for High-Functioning Teams

The incorporation of multiple perspectives in health care offers the benefit of diverse knowledge and experience; however, in practice, shared responsibility without high-quality teamwork can be fraught with peril. For example, “handoffs,” in which one clinician gives over to another the primary responsibility for care of a hospitalized patient, are associated with both avoidable adverse events and “near misses,” due in part to inadequacy of communication among clinicians. [8,9,10,11,12] In addition to the immediate risks for patients, lack of purposeful team care can also lead to unnecessary waste and cost. [13] Given the frequently uncoordinated state of care by groups of people who have not developed team skills, it is not surprising that some clinicians report that team care can be cumbersome and may increase medical errors. [14] By acknowledging the aspects of collaboration inherent in health care and striving to improve systems and skills, identification of best practices in interdisciplinary team-based care holds the potential to address some of these dangers, and might help to control costs. [15,16] Identifying best practices through rigorous study and comparison remains a challenge, and data on optimal processes for team-based care are elusive at least partly due to lack of agreement about the core elements of team-based care. Once the underlying principles are defined, researchers will be able to more easily compare team-based care models, payers will be able to identify and promote effective practices, and the essential elements for promoting and spreading team-based care will be evident.

The State of Play

The high-performing team is now widely recognized as an essential tool for constructing a more patient-centered, coordinated, and effective health care delivery system. As a result, a number of models have been developed and implemented to coordinate the activities of health care providers. Building on foundations established by earlier reports from the IOM [17] and the Pew Health Professions Commission, [18] team-based care has gained additional momentum in recent years in the form of legislative support through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 and the emergence of substantial interprofessional policy and practice development organizations, such as the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative and the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC).

In addition to national initiatives, there are many deeply considered, well-executed initiatives in team-based care in pockets across the United States. High-functioning teams have been formed in a variety of practice environments, including both primary and acute care settings. [1,19,20,21,22,23,24] Teams have also been formed to serve specific patients or patient populations, for example, chronic care teams, hospital rapid response teams, and hospice teams. [25,26,27]

Analyses of the quality and cost of team-based care do not yet provide a comprehensive, incontrovertible picture of success. Still, two reviews indicate that team-based care can result in improvements in both health care quality and health outcomes, and one review indicates that costs may be better controlled, particularly in transitional care models. [16,28] Research on team-based care has been hindered by lack of common definitions. While common elements, success factors, and outcome measures are beginning to be described in a variety of team-based care scenarios, a widely-accepted framework does not yet exist to understand, compare, teach, and implement team-based care across settings and disciplines.

Fundamental to the success of any model for team-based care is the skill and reliability with which team members work together. Team function has been described in one conceptualization as a spectrum running from parallel practice, in which clinicians mostly work separately, to integrative care, in which the interdisciplinary team approach is pervasive and nonhierarchical and utilizes consensus building, with many variations along the way. [29] It is likely that the appropriate team structure varies by situation, as determined by the needs of the patient, the availability of staff and other resources, and more. A unifying set of principles must not only acknowledge this variation but embrace as formative the underlying situation-defined needs and capacities.

Despite the pervasiveness of people working together in health care, the explicit uptake of interprofessional team-based care has been limited. At the most basic level, establishing and maintaining high-functioning teams takes work. In economic terms, if the transaction costs of team functioning outweigh the benefit to team members, there is little incentive to embark on the journey toward formal team-based care. [30 Some of the specific costs that may be restraining forces include lack of experience and expertise, cultural silos, deficient infrastructure, and inadequate or absent reimbursement. [31] These barriers were outlined in a 2011 conference convened by the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the ABIM Foundation in collaboration with IPEC. The publication of the proceedings, Team-Based Competencies: Building a Shared Foundation for Education and Clinical Practice, identified key barriers to change, including the absence of role models and reimbursement, resistance to change, and logistical barriers.

Despite these barriers, teams are built and maintained. Researchers have identified facilitators of team-based care, or factors that constitute and promote good teams and teamwork. For instance, Grumbach and Bodenheimer found that key facilitators include having measurable outcomes, clinical and administrative systems, division of labor, training of all team members, effective communication, and leadership. [1,30] IPEC has focused on effective interprofessional work and has defined four domains of core competencies: values/ethics, roles/responsibilities, communication, and teamwork/team-based care. [32]

Our aim is to build from this prior work to identify a set of core principles underlying team-based care across settings, as well as the essential values that are common to the members of high-functioning teams throughout health care. By doing so, we hope to help reduce barriers to team-based care, while supporting the facilitators of effective teamwork in health care.

Approach

The authors are individuals knowledgeable about team-based care who participated in an interprofessional work group that was drawn from the IOM’s Best Practices Innovation Collaborative. To achieve the goal of identifying basic principles and values for interprofessional team-based care, we first synthesized the factors previously identified in various health care contexts, then took these distilled principles to the field to understand how well they represent team-based care in action. We held monthly conference calls between October 2011 and June 2012 with frequent e-mail collaboration in the intervals. We then reviewed the health professions’ and “gray” literature and discussed common elements. Using this information, we drafted a definition of team-based care and a sample set of principles and values critical to team-based care. To test the applicability and validity of the principles and values, and to understand their on-the-ground actualization, we performed “reality check” interviews with members of team-based health care practices. Teams with various compositions, practice settings, and patient profiles were identified around the country through the literature review and the input of experts. A draft of the team-based care definition, principles, and values was sent to teams in advance of a telephone interview. We then interviewed members of the teams by telephone during January 2012 using a semi-structured approach. Based upon the results of the interviews, we refined the team-based care principles and values, identified key themes, and added illustrative examples.

A Proposed Definition of Team-Based Health Care

To inform a proposed definition of team-based care, we reviewed the literature and reflected on the definitions and factors identified in prior work. Elements found across the definitions we reviewed include the patient and family as team members, more than one clinician, mutual identification of the preferred goal, close coordination across settings, and clear communication and feedback channels. Ultimately, we chose to adapt the definition developed through a detailed literature review and consensus process by Naylor and colleagues. [28] Although this definition was developed for use in the context of primary care for chronically ill adults, its core elements were easily adapted to apply to the work of teams across settings:

Team-based health care is the provision of health services to individuals, families, and/or their communities by at least two health providers who work collaboratively with patients and their caregivers—to the extent preferred by each patient—to accomplish shared goals within and across settings to achieve coordinated, high-quality care. [28]

Values

In the process of considering and refining the principles of team-based care, we noted that while teams are groups, they are also made up of individuals. In addition to particular behaviors that facilitate the function of the team, we heard from the teams we interviewed that certain personal values are necessary for individuals to function well within the team. This harmonizes with the core competency domain of “values/ethics” put forward in IPEC’s Team-Based Competencies.

The following are five personal values that characterize the most effective members of high-functioning teams in health care.

- Honesty: Team members put a high value on effective communication within the team, including transparency about aims, decisions, uncertainty, and mistakes. Honesty is critical to continued improvement and for maintaining the mutual trust necessary for a high-functioning team.

- Discipline: Team members carry out their roles and responsibilities with discipline, even when it seems inconvenient. At the same time, team members are disciplined in seeking out and sharing new information to improve individual and team functioning, even when doing so may be uncomfortable. Such discipline allows teams to develop and stick to their standards and protocols even as they seek ways to improve.

- Creativity: Team members are excited by the possibility of tackling new or emerging problems creatively. They see even errors and unanticipated bad outcomes as potential opportunities to learn and improve.

- Humility: Team members recognize differences in training but do not believe that one type of training or perspective is uniformly superior to the training of others. They also recognize that they are human and will make mistakes. Hence, a key value of working in a team is that fellow team members can rely on each other to help recognize and avert failures, regardless of where they are in the hierarchy. In this regard, as Atul Gawande has said, effective teamwork is a practical response to the recognition that each of us is imperfect and “no matter who you are, how experienced or smart, you will fail.” [2]

- Curiosity: Team members are dedicated to reflecting upon the lessons learned in the course of their daily activities and using those insights for continuous improvement of their own work and the functioning of the team.

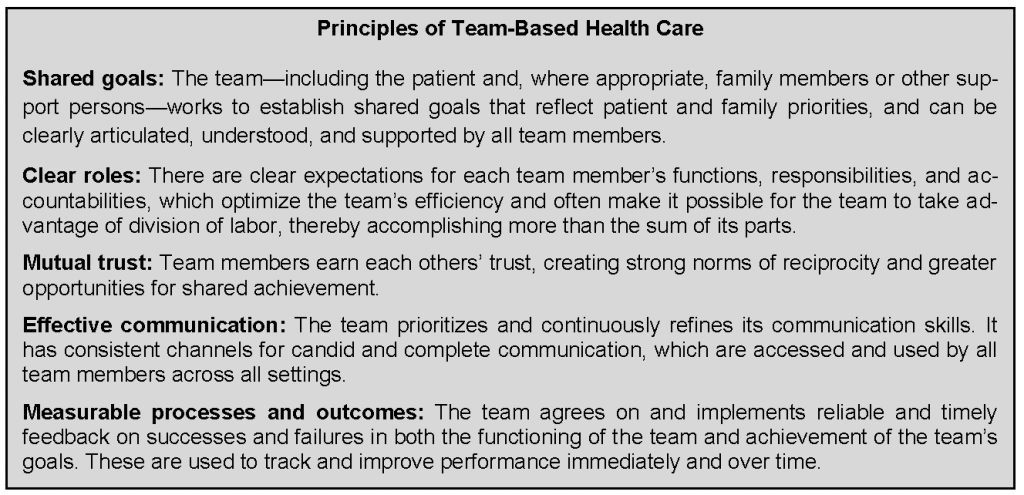

Principles of Team-Based Care

Each health care team is unique—it has its own purpose, size, setting, set of core members, and methods of communication. Despite these differences, we sought to identify core principles that embody “teamness.” After reviewing the literature and published accounts of team processes and design, five principles emerged: shared goals, clear roles, mutual trust, effective communication, and measurable processes and outcomes. These principles are not intended to be considered in isolation—they are interwoven, and each is dependent on the others. Eleven teams across the nation considered the principles, verified and clarified the meaning of each, and described how each comes into play in their own team environments. Descriptions of the teams are listed throughout. The following section describes each of the principles in detail, provides examples from the teams we interviewed, and considers organizational factors to support development of teams that cultivate these five principles, as well as the values that support high-quality team-based health care. Arguably, the most important organizational factor supporting team-based health care is institutional leadership that fully and unequivocally embraces and supports these principles in word and action. [33]

Shared Goals

The team—including the patient and, where appropriate, family members or other support persons—works to establish shared goals that reflect patient and family priorities, and that can be clearly articulated, understood, and supported by all team members.

The foundation of successful and effective team-based health care is the entire team’s active adoption of a clearly articulated set of shared goals for both the patient’s care and the team’s work in providing that care. Although obvious to some extent, the explicit development and articulation of a set of shared goals, with the active involvement of the patient, other caregivers, and family members, does not happen easily or by chance. We found that teams shared several strategies and practices with regard to establishing shared roles.

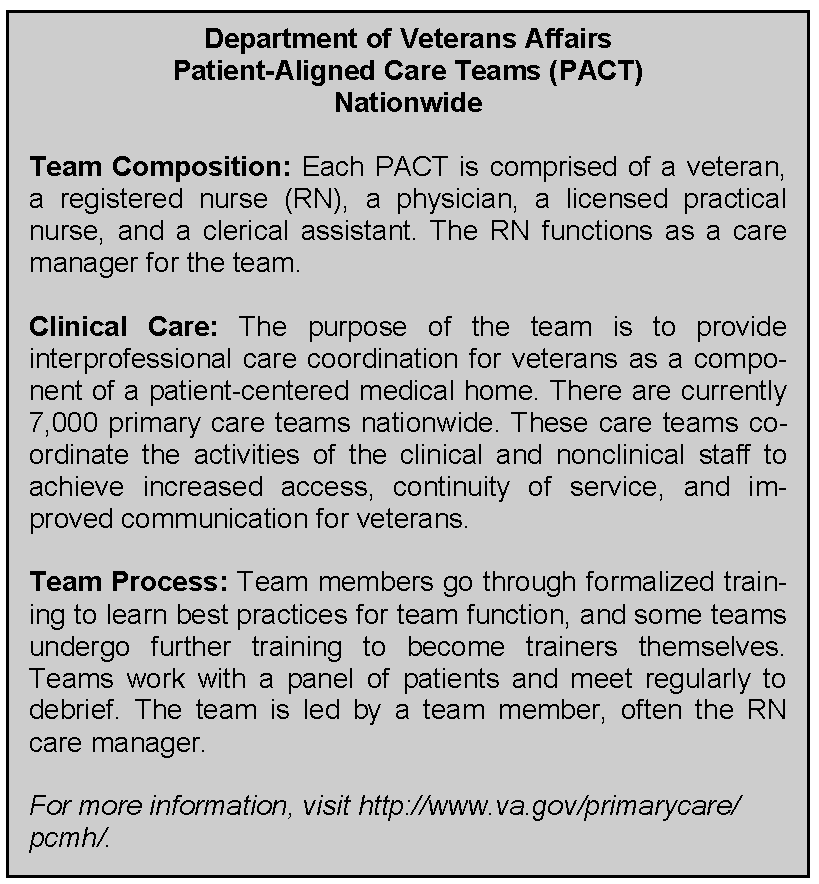

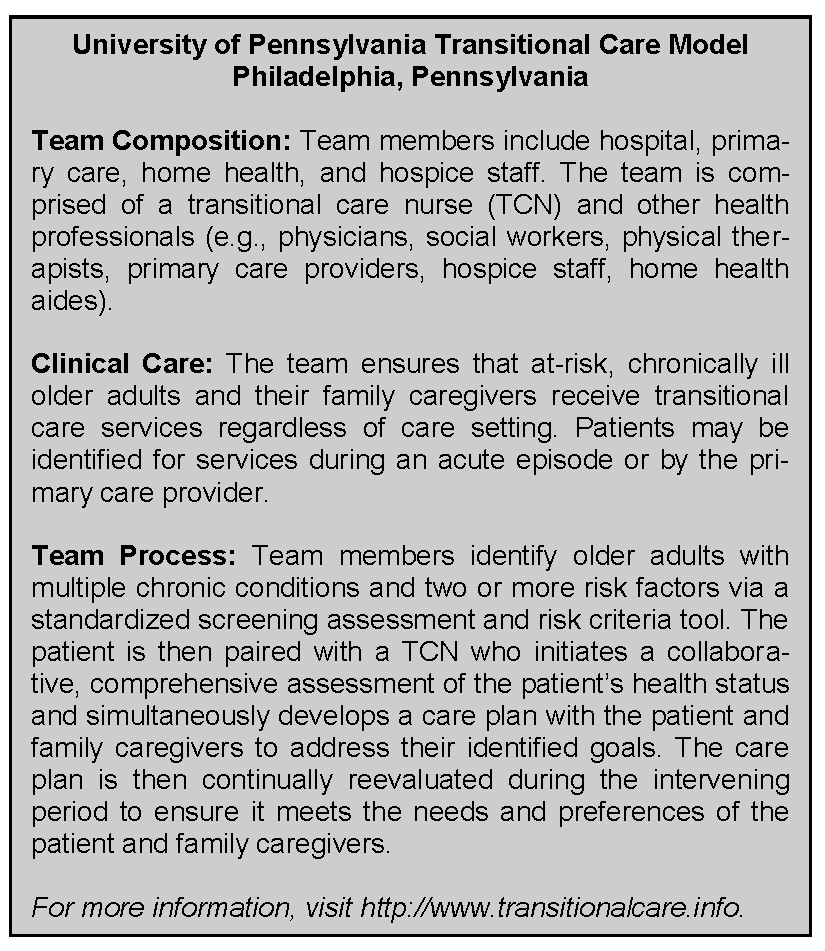

First, the patient, caregivers within the family, and the family itself must be viewed and respected as integral members of the team. High-functioning teams in health care strive to organize their mission, goals, and performance seamlessly around the needs and perspective of patients and families. This element is central to the most forward-thinking team-based care and represents a central tenet of a social compact between health care professionals and society. [34] As an example, this commitment to patient involvement in the team is central to team training within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patient-aligned care team, which emphasizes that without the veteran (the patient), the team has no mission or goal. Team members are taught to think of things from the veteran’s point of view and align the team’s concerns and actions with those of the veteran. This “patient-centered” attitude is embedded in many of the teams interviewed, including the University of Pennsylvania Transitional Care Model, in which team members acknowledge explicitly that the patient and family are the ones who truly “own” the plan of care. (As described by Berwick (2009), patient-centeredness reflects an “experience (to the extent the informed, individual patient desires it) of transparency, individualization, recognition, respect, dignity, and choice in all matters—without exception—related to one’s person, circumstances, and relationships in health care.”)

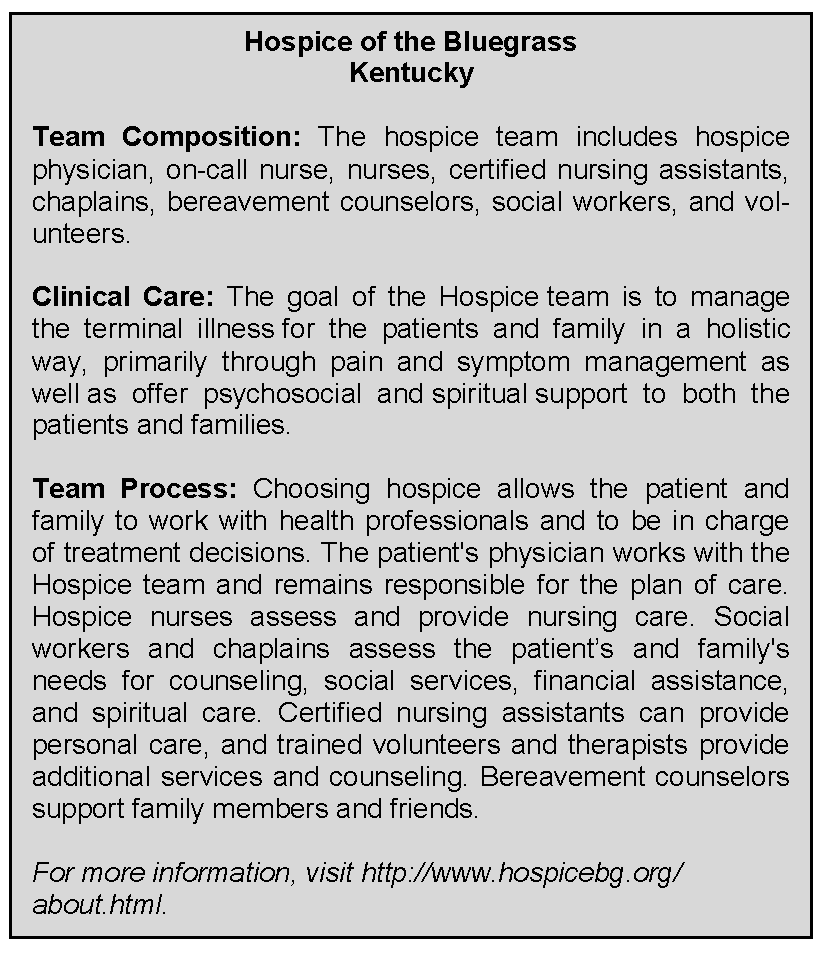

Second, as part of integrating the patient into the team, high-functioning teams fully and actively embrace a shared commitment to the patient’s key role in goal setting. Many teams interviewed used their first meetings with the patient and family, or an initial “intake” interview, to begin the process of developing shared goals. The patient and family meeting is the tool employed by team members at Hospice of the Bluegrass, for example, to help team members develop a shared understanding of the full extent of the patient and family’s needs, which are then translated into stated goals of care. To engage in a full discussion, they noted, it is especially important for the team to be clear with the patient and family about all the types of needs the team is prepared to fulfill. Patients and families may not expect the full extent of services available. When such a comprehensive approach to patient needs is taken, though, patients and families are grateful to know that the team will collaborate with them to meet their needs to the extent possible.

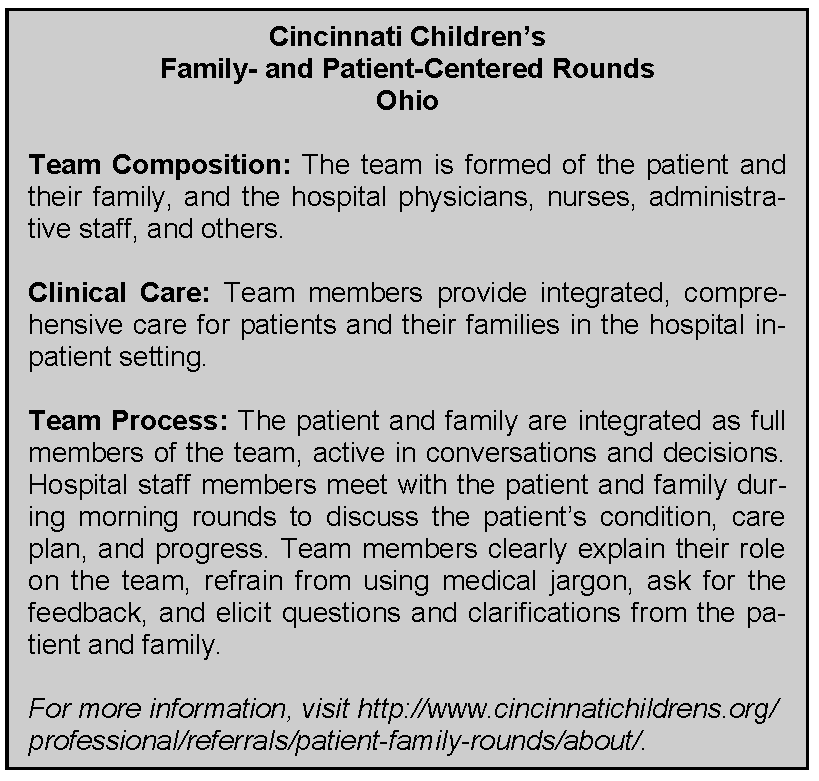

Third, teams regularly evaluate their progress toward the shared goals and work together with patient and family members to refine and move toward achievement of these goals. At Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, this monitoring and updating takes place daily during patient- and family-centered rounds. Core elements of daily rounds include reviewing together the events of the past 24 hours, creating a daily assessment and plan of care, and reviewing and updating criteria for and progress toward hospital discharge. This process ensures that the team both reaffirms with regularity the applicability of the shared goals and offers an opportunity for clarification of intent and prevention of misunderstandings.

Organizational factors that enable development of shared goals include

- Providing time, space, and support for meaningful, comprehensive information exchange between and among team members, particularly when a new team forms—for example, when a new patient/family begins to work with the team.

- Facilitating establishment and maintenance of a written plan of care that is accessible and updatable by all team members.

- Supporting teams’ capacity to monitor progress toward shared goals for the patient/family and the team.

The perspectives and experiences shared in the interviews strongly support the foundational nature of shared goals within the larger framework of team-based care principles. To achieve shared goals that are meaningful and robust, the patient and family must be integrally involved as members of the team in developing, refining, and updating the goals. While shared goals are the roadmap guiding the work of the team, the development and execution of these goals is dependent upon the other principles that follow. Clear roles, mutual trust, and effective communication among team members are essential for work to be done and goals to be met. Measurable processes and outcomes determine the level of success, help to refine goals over time, and guide improvement.

Clear Roles

There are clear expectations for each team member’s functions, responsibilities, and accountabilities, which optimize the team’s efficiency and often make it possible for the team to take advantage of division of labor, thereby accomplishing more than the sum of its parts.

Members of health care teams often come from different backgrounds, with specific knowledge, skills and behaviors established by standards of practice within their respective disciplines. Additionally, the team and its members may be influenced by traditional, cultural, and organizational norms present in health care environments. For these reasons it is essential that team members develop a deep understanding of and respect for how discipline-specific roles and responsibilities can be maximized to support achievement of the team’s shared goals. Attaining this level of understanding and respect depends upon successful cultivation of the personal values necessary for participating in team-based care, noted above. Training and working in interdisciplinary settings where these values are foundational also allows the team to safely challenge the boundaries of traditional roles and responsibilities to meet the needs of the patient.

Integrating patients and families fully into the team represents a particular challenge that requires careful planning. Patients and families are unique members of the team in several ways. First, patients and families often do not have formal training in health care. Although different health professionals may, at times, speak “different languages,” if patients and families are to be full members of the team, they must understand their fellow team members. Second, a number of different patients and families typically come in and out of the team many times per day. This requires continual adaptation by other team members who must “shift gears” as they form and reform teams on a regular basis. Finally, just as clinicians must adapt to the various patients they encounter, so, too, must patients learn the rules and customs of each new health care team with which they interact. Processes that introduce—and reintroduce—the patient and family to the roles, expectations, and rules of the team are critical if they are to participate as full members of the team.

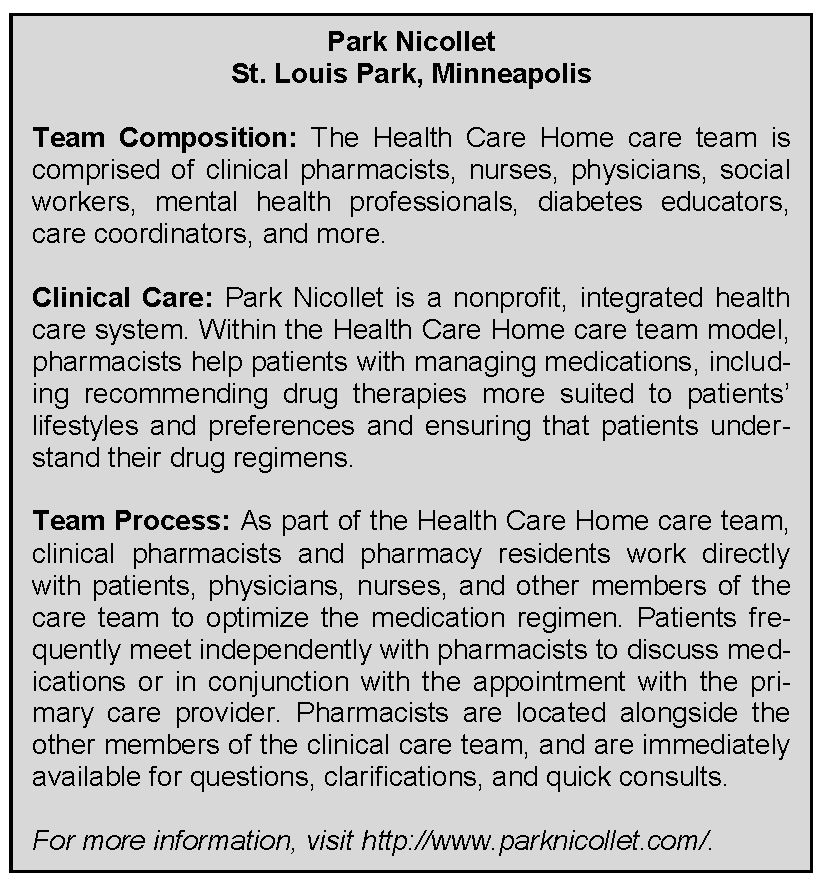

Managing a team is challenging and becomes especially so as the membership increases and includes some or all of the following disciplines: licensed physical and mental health professionals (e.g., nurses, physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, social workers, psychologists, pharmacists, physical, occupational and speech therapists, and dieticians); personal care providers (e.g., certified nurse aides and home health aides); community providers (e.g., spiritual care, community-based support, and social media); and the patient, family, and others close to the patient. In addition, it is possible to have teams integrated into larger teams. An example of this is the medication management team at Park Nicollet, which collaborates with and is a part of the Health Care Home team. To establish clear roles that support “teamness,” the teams we interviewed engage a number of strategies and practices.

First, team members determine the roles and responsibilities expected of them based on the shared goals and needs of the patient and family. At Hospice of the Bluegrass, team members anticipate a broad spectrum of patient and family needs that may, to some extent, alter the way in which they perform their professional duties. Following the patient and family meeting, in which the team identifies needs and goals that range from treating pain to addressing food insecurity to engaging spiritual services, the team members then lay out how they will intervene to maximize resources. This maximization may include adding responsibilities to particular team members’ work. For example, if the services of a chaplain are primarily required, he or she may also take on the responsibility of bringing supplies to the home, or asking about the level of pain. Inherent in these shared responsibilities is the identification of needs that require the knowledge and skills of other team members.

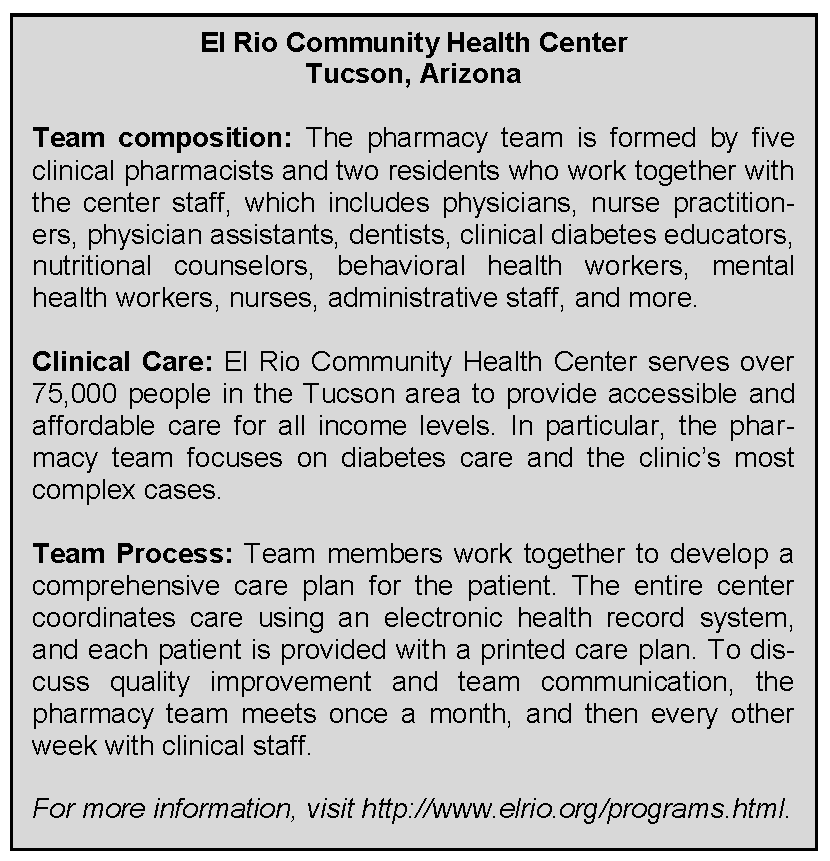

Second, team members must engage in honest, ongoing discussions about the level of preparation and capacities of individual members to allow the team to maximize their potential for best utilization of skills, interests, and resources. This frankness allows the team to inventory the discipline-specific assets of team members and ensure that they are creatively aligned with the team’s shared goals. Once they have engaged in the process of matching patient goals to needed roles and planning for the best utilization of team resources, team members must have the autonomy to implement these plans. For example, at El Rio Community Health Center, the clinical pharmacist serves as the primary care provider for patients with diabetes and comorbid conditions, such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia, requiring complex medication management. This occurs through a medical staff–approved collaborative practice agreement in which the pharmacist provides appropriate diagnostic, educational, and therapeutic management services, including prescribing medication and ordering laboratory tests, based on national standards of care for diabetes. [35] The arrangement is sharply focused on the needs of the patient while maximizing the expertise of health professionals in the clinic.

Third, while roles and responsibilities must be clearly defined and explicitly assigned, team members must anticipate and embrace flexibility as needed. For example, a challenge faced by patient-aligned care teams in the VA is the absence of personnel. If no replacement exists for an absent team member, then the team can become dysfunctional. Thus, while clear roles must exist to enable accountability and creativity, effective communication and flexibility must be built into the fabric of the team to ensure that seamless coverage is available. Building in flexibility requires that team members understand to the greatest extent possible the background, skillsets, and responsibilities of their teammates.

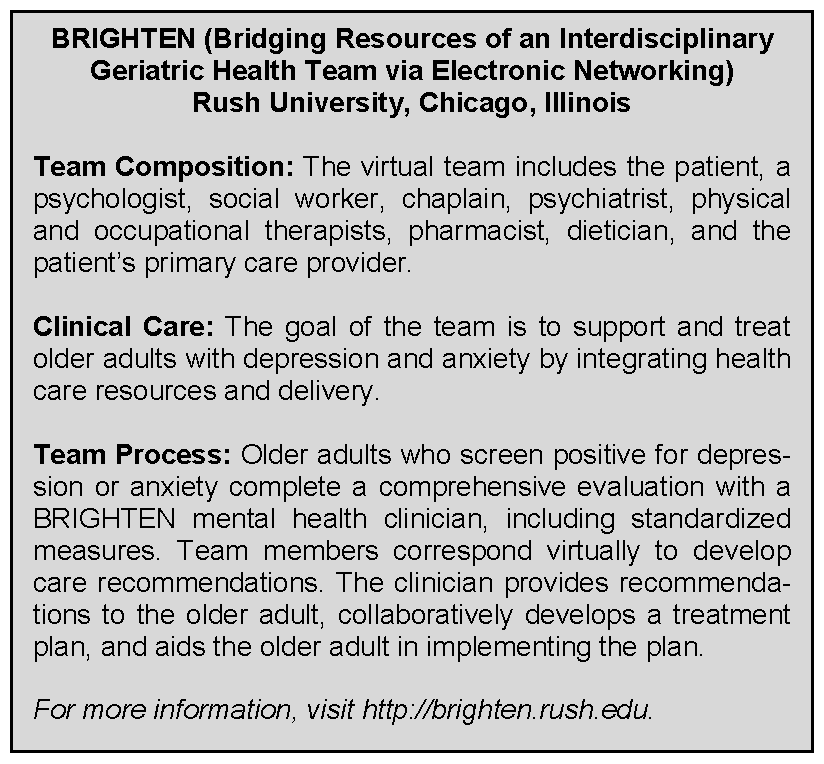

Fourth, team members must seek the appropriate balance between roles and responsibilities that fall to individual team members and those that are better accomplished collaboratively. Given the high transaction costs of using a team, clear roles help facilitate decisions about the appropriate engagement of multiple team members in particular scenarios. For example, the BRIGHTEN (Bridging Resources of an Interdisciplinary Geriatric Health Team via Electronic Networking) program at Rush University in Chicago finds that occasionally issues arise at team meetings that do not concern all team members or that are best handled by one or two team members alone. To flag these items and facilitate the work that requires full team engagement, the team has a standing rule that issues involving one or two team members will be handled outside of team meetings.

Finally, all teams have certain roles and responsibilities that are routinely indicated to support the team’s functioning. These roles include team leadership, record keeping, and meeting facilitation, as well as other administrative tasks. Carrying out routine tasks requires the team to utilize their resources creatively while avoiding pretense and superiority in the process. Routine tasks should be assigned in a manner similar to patient care tasks—balancing patient need, team goals, and local resources. Teams should determine which member is most appropriate for the role, recognizing that some roles may be best rotated across the team.

The issue of team leadership has sometimes been contentious, especially when approached in the political or legal arenas, where questions about team leadership often become entangled in professional “scope of practice” issues. In particular, arguments have arisen around “independent practice” versus team-based care and, where care is team-based, whether all team functions must be “physician-led,” and what this would imply for other health professionals with regard to care management decision making. These debates are taking place in many states, with a number of potential solutions taking shape, and this paper does not aim to resolve them. However, our interviews produced two potentially helpful observations. First, these questions seem much less problematic in the field than they are in the political arena. Among the teams we interviewed, notions of “independent practice” were not relevant because no one member of the team was seen as practicing alone, and leadership questions were not sources of conflict; rather, when leadership issues were raised they were portrayed as matters for open discussion that led to mutually agreeable solutions. Second, this relative lack of conflict might be because these teams use the term “leadership” in a nuanced way.

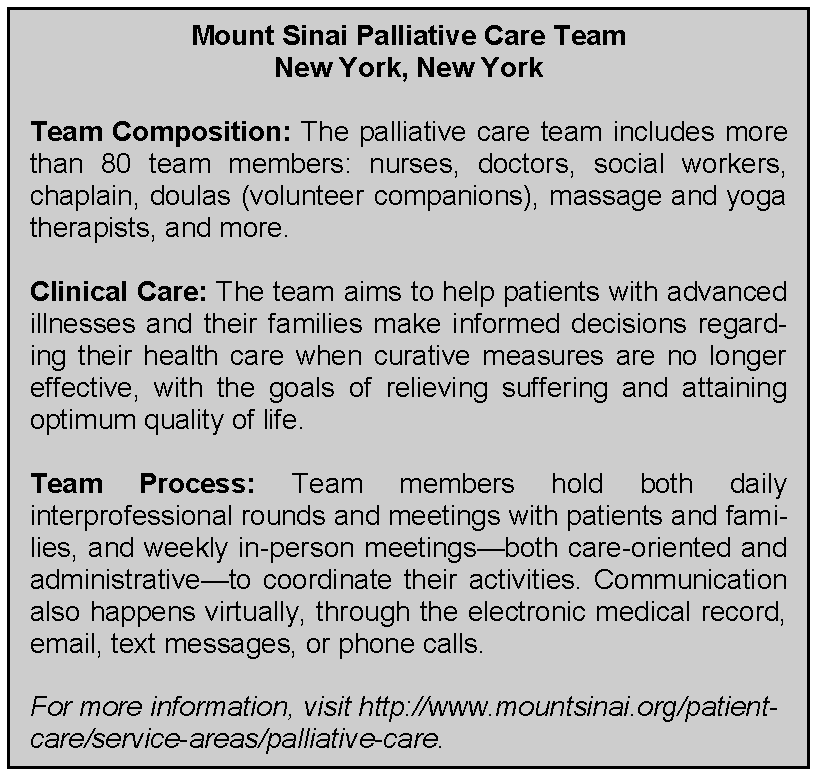

There is widespread agreement that effective teams require a clear leader, and these teams recognize that leadership of a team in any particular task should be determined by the needs of the team and not by traditional hierarchy. For example, the Mount Sinai palliative care team identified the need to improve a weekly clinical care meeting. They identified the main goal for the meeting: addressing complex patient issues in a context that ensured that each team member had an equal voice. The team assessed the training and skillsets of all team members, and, based upon the goal, determined—somewhat surprisingly, yet successfully—that the chaplain was the best person to run the clinical care meeting. This example nicely illustrates that being an effective team leader for a particular task (like running a team meeting) can require a set of skills that are distinct from those required for making clinical decisions.

While the teams we interviewed acknowledged that physicians are clinically and often legally accountable for many team actions, the physicians on the teams we interviewed were not micromanagers; instead, they were collaborators who did not seek or exercise authority to override decisions best made by other team members with particular expertise, whether in social work, chaplaincy, or care coordination, etc.

Since roles on the team vary by both professional capability as well as function, patients and their caregivers must be fully informed about these roles. Each team member should communicate his or her role clearly and solicit input from others, especially the patient and family, so that all responsibilities are clearly defined and understood. For example, at Park Nicollet, clinical pharmacists and pharmacy residents are placed directly next to other care providers to answer any questions that arise in the course of clinical care, as well as to make it apparent that all care providers work together. Likewise, during rounds at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, all members of the team introduce themselves to each patient and family by name and then describe how they contribute to the team in clear language. Roles and responsibilities are discussed verbally and written into the care plan. The team explicitly solicits all opinions, including those of the patient and family.

While team members’ expertise and skills should be tailored to the needs of the patient, it is also important to recognize when unintended or unforeseen consequences may occur. The experience and skills of team members are likely to overlap, with the potential for confusion or frustration about roles and responsibilities, possibly leading to misunderstandings and disruption in care to the patient. For example, within the Park Nicollet medication management group, multiple team members are skilled and experienced in aspects of diabetes care and management. Team members work together to identify clearly the roles and responsibilities for which they are best suited, ensuring that roles are discrete and that the experience is harmonized for patients. After roles and responsibilities are clarified, team members may, at times, find themselves in situations for which they feel ill-prepared or are not comfortable. To ensure that team members are empowered to seek support at any time, the team must foster an environment of continuous learning in which seeking advice or help is considered a strength and rewarded. In a high-functioning team environment, team members will hold significant responsibility and accountability. To foster success rather than stress, the team must establish transparent and measurable expectations related to roles and responsibilities, for each individual member and for the team as a whole.

Organizational factors that enable establishing and maintaining clear roles include

- providing time, space, and support for interprofessional education and training, including explicit opportunities to practice the skills and hone the values that support teamwork.

- facilitating communication among team members regarding their roles and responsibilities.

- redesigning care processes and reimbursement to reflect individual and team capacities for the safe and effective provision of patient care needs.

Regardless of a team’s setting, size, or member characteristics, roles and responsibilities must be clear and accountability expected. Yet, despite the best of intentions, teams are not immune to the inherent norms of health care delivery systems. Even effective teams with clear roles and responsibilities may experience the emergence of silos of care, decreased teamwork, or delayed engagement of needed personnel or resources within their group. A team with well-articulated roles and responsibilities grounded in the values of honesty, discipline, creativity, humility, and curiosity fosters an environment where any team member feels safe bringing such concerns to the forefront for discussion, proactive improvement, and prevention.

Mutual Trust

Team members earn each other’s trust, creating strong norms of reciprocity and greater opportunities for shared achievement.

Trust is the current that flows through the team, allowing team members to rely upon each other personally and professionally and enabling the most efficient provision of health care services. Achieving a team with norms of mutual trust requires establishing trust, maintaining trust, and having provisions in place to address questions about or breaches in trust. When a strong trust fabric is woven, team members are able to work to their full potential through relying on the assessments and information they receive from other team members, as well as the knowledge that team members will follow through with responsibilities or will ask for help if needed. The BRIGHTEN team explained that actively developing trust in team members allows them to learn from and build on each other’s assessments and conclusions and permits nonduplication of work.

Establishing and maintaining trust requires that each team member hold true to the personal values of honesty, discipline, creativity, humility, and curiosity, which together support the creation of an environment of mutual continuous learning. The Mount Sinai palliative care team emphasized the importance of setting the stage for trust as early as the hiring process. Using shared values as the basis for selecting team members is critical to ensuring that the norms that support a trusting environment are upheld. This team finds that “shoehorning” someone into the team can be very harmful. The hiring process has been carefully amended to ensure that professional and personal values and skills will nurture, and be nurtured by, the team.

In a clinical setting, providing excellent patient care is the direct outcome of implementing personal values in the context of professional skill. At El Rio Community Health Center, a key element of building team members’ trust in each other is documenting the contribution of each team member and professional group to high-quality patient care and outcomes. Making these data transparent to the whole team generated better understanding of and appreciation for team members’ contributions, as well as the potential gains in efficiency and effectiveness possible through leveraging team members’ capacities in purposeful team-based care.

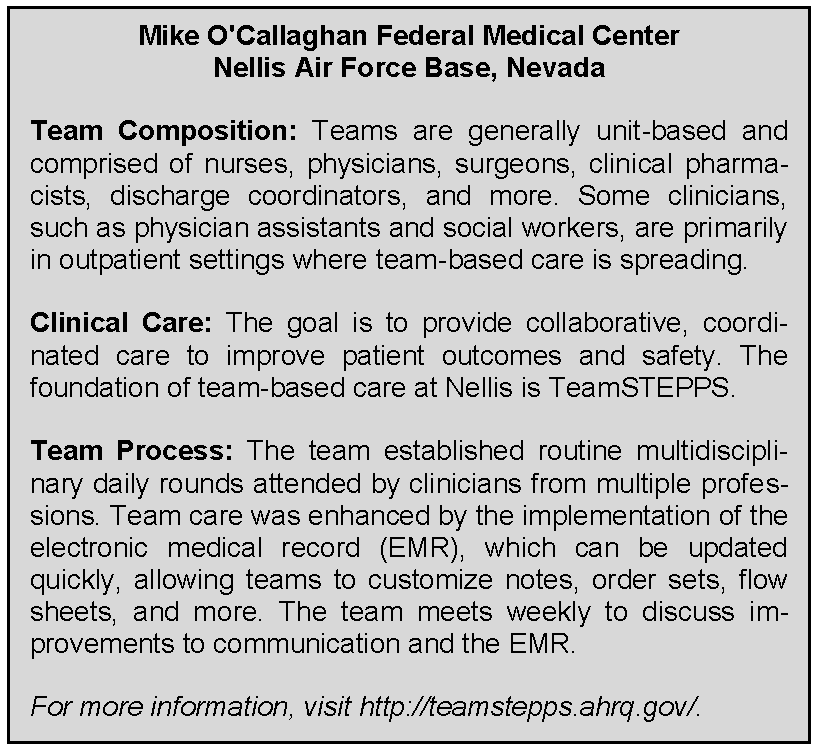

In addition to carrying outpatient care duties professionally, a critical element of trust is understanding and respecting the rules and culture of the team. Many teams said that a critical element to establishing trust among team members is ensuring that all voices on the team are heard equally. At Nellis Air Force Base, the ethos is that, regardless of military rank, everyone is expected to raise questions or concerns. To facilitate a safe and trusting environment in which more junior team members can speak up, incentives are aligned to encourage leaders to listen with open minds and address team members’ questions and concerns.

The importance of personal connections among team members as an instrument for building trust was endorsed by some teams. The BRIGHTEN team refers specifically to their “culture of cake,” in which team members’ significant events are celebrated at meetings, with cake. The cake does not derail the purpose of the meeting—the celebration is part and parcel of the work of the team, while at the same time, team members focus on their joint tasks. The Mount Sinai palliative care team has a monthly birthday celebration for members of their team at which there are no clinical or administrative tasks. Nellis Air Force Base has team- and community-building activities throughout the year—for example, picnics or bowling—so that individuals can get to know each other on a personal level.

Developing and maintaining trust with patients and families may require special consideration, as they may not have the longevity on the team or daily working relationship shared by other team members. Clinician members of the team can develop trust with patients and families by using effective communication to explain the process of developing shared goals and establishing clear roles. By being accountable and following through with these principles, patients and families will come to trust the values of other team members. Clinician members may benefit from learning skills formally to build trust with patients and families. Negotiation and conflict management skills may be particularly valuable. For example, at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, team members are taught to make themselves “vulnerable” by stepping out of their traditional roles and looking through the eyes of the patient and family in order to find common ground as a starting point for mutual trust.

Organizational factors that facilitate development of mutual trust include

- Providing time, space, and support for team members to get to know each other on a personal level.

- Embedding in education and hiring processes the personal values that support high-functioning team-based care.

- Developing resources and skills among team members for effective communication, including conflict resolution.

Mutual trust enables team members to set clear goals and achieve shared goals in a harmonious, efficient fashion. Fundamentally, mutual trust enables these by setting the foundation for good communication, which is the focus of the following principle. As with each of these principles, mutual trust and effective communication are tightly linked and mutually supportive. Thus, the signs of mutual trust in a team include not only elements of team function, such as equal participation and facilitative leadership style, but also outcomes such as successful quality improvement efforts and redesigned care processes in which team members build on each other’s work. In the preoperative surgery unit at Nellis Air Force Base, the team established continuous note charting in the electronic medical record. The preoperative nurse, surgeon, anesthesiologist, and others use one running note to chart their observations and plans, maximizing the utility of their collaborative work.

Effective Communication

The team prioritizes and continuously refines its communication skills. It has consistent channels for candid and complete communication, which are accessed and used by all team members across all settings.

If the team members are unable to provide information and understanding to each other actively, accurately, and quickly, subsequent actions may be ineffective or even harmful. In the digital age, team communication is not limited to in-person communication, such as in team meetings. It incorporates all information channels—progress notes and electronic health records, telephone conversations, e-mail, text messages, faxes, and even “snail mail.” Many channels of communication may be employed by team members to achieve their purposes. The framing and content of that communication is the core of effective communication. Effective communication should be considered an attribute and guiding principle of the team, not solely an individual behavior. Effective communication requires incorporation of all of the values underlying effective teams: honesty, discipline, creativity, humility, and curiosity. Effective communication also comprises a set of teachable skills that can be developed by each member of the team and by the team as a whole. The teams we interviewed employed a number of strategies and skills for developing and employing effective communication.

First, setting a high standard for, and ensuring, consistent, clear, professional communication among team members is a core function of a high-performing team. The BRIGHTEN program employs the Rush University Medical Center Geriatric Interdisciplinary Team Training Program guide to the fundamentals of effective teamwork. The guide outlines individual and team communication practices that support effective teamwork. [36] For example, team members should speak clearly and directly in a succinct manner that avoids jargon, while drawing upon their professional knowledge. They should tend toward discussing verifiable observations rather than personal opinion. Team members should listen actively to each other and show a willingness to learn from others. The need for these strategies is highlighted by the fact that many of the teams we interviewed indicated that allowing everyone an equal voice in the room is a core practice. At Park Nicollet, interprofessional care is facilitated when all are encouraged to attend team meetings and encouraged to ask questions and share ideas equally. The skills outlined are also critical for the University of Pennsylvania Transitional Care Team, which works with the patient, family, inpatient care team, and outpatient providers to ensure that the patient’s care plan is followed while ensuring that all providers’ roles and responsibilities are honored.

Second, effective communicators are deep listeners—actively listening to the contributions of others on the team, including the patient and family. Individuals on the team need to be able to listen actively and model this for others on the team by clarifying or elaborating key ideas, reflecting thoughtfully on value-laden or controversial “hot-button” issues. Team members may need to help each other improve this skill either through team exercises or individual conversations. Patients and families often participate more as listeners on the team; their contributions may need to be facilitated through the active listening of other team members. Team members may need to coach each other, including patients and families, in succinct and clear contributions. Team members should recognize that questions are a valuable way to clarify and to learn from each other. Teams that perform patient- and family-centered rounds at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital engage listening at many levels. First and foremost, central to rounds is the elicitation, on the first day, of the patient and family’s preference for participation (or nonparticipation) in team rounds. Whatever option patients and families choose, the plan of care and daily work are defined by the goals and concerns expressed by the patient and family. Active listening—with confirmation of information transfer —is fundamental to the rounds. Pediatric interns who present the events of the past 24 hours to the team are taught to confirm the report with the patient and family. Since orders are entered into the computer during rounds, a final step is an official “read-back” of those orders, ensuring accuracy and preventing errors.

Finally, team communication requires continual reflection, evaluation, and improvement. Recognizing signs of tension and unspoken conflict can serve as a trigger to reexamine the communication patterns of the team.

Both individual and team communication skills are teachable and learnable. [37,38] Individuals should be able to use a wide range of effective communication techniques, recognize when their own or the team’s communications are not functioning well, and act as a facilitator. One or more individual team member may act as a coach for patients and families not accustomed to or comfortable with active team membership and communication. (For more information, visit http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/ethics/research-ambulatory-patient-safety.pdf.) Fundamentals of effective team communication include the active membership of the patient and family and the willingness and capability of team members to be clear and direct and communicate without technical jargon. Information sharing is the goal of communication, and all team members need to recognize that this includes both technical and affective information.

Organizational factors that sustain effective communication include

- providing ample time, space, and support for team members to meet—in-person and virtually—to discuss direct care as well as team processes.

- ensuring that team members are trained in shared communication expectations and techniques.

- utilizing digital capacity—including the electronic medical record, e-mail, Web portals, personal electronic devices, and more—to facilitate easy, continuous, seamless, transparent communication among team members, with a special focus on inclusion of patients and families.

As an example of this last factor, at MD Anderson Cancer Center, patients can access their full medical records and communicate virtually with team members through the myMDAnderson Web portal. The uptake of this service has been enormous and patient and provider satisfaction with the service is high.

Measurable Processes and Outcomes

The team agrees on and implements reliable and timely feedback on successes and failures in both the functioning of the team and achievement of the team’s goals. These are used to track and improve performance immediately and over time.

High-functioning teams, by definition, have embraced or at least integrated the principles of team-based care noted above. The high-functioning team has agreed upon shared goals for delivery of patient-centered care. Clear roles and responsibilities have been shared across the team and team members have committed to shared accountability. High-functioning teams recognize the importance of trust in all interactions, and actively work to build and maintain a respectful and trusting environment. Effective communication is at the core of the team’s work and is apparent in all encounters among team members, patients, and other participants in the care process.

Once they employ these principles, how do teams know they are high-functioning? How can teams that are initially forming assess their progress? How can teams that have been disrupted or lost some functionality understand what efforts are needed to regain it? And, how can teams know that they are improving care and outcomes while controlling costs to the best of their ability? Only through rigorous, continuous, and deliberate measurement of the team’s processes and outcomes can potential barriers be identified and strategies developed to overcome them. Measurement of team effectiveness is not a new science. Other industries which employ highly educated, strongly motivated professionals with complimentary or overlapping responsibilities in high-pressure, high-risk situations like aviation, nuclear power, and the armed services have developed a significant body of literature on measuring the effectiveness of teamwork. Only recently, with higher levels of attention given to patient safety and high-quality care, has health care begun explicitly to create and measure team-based health care delivery.

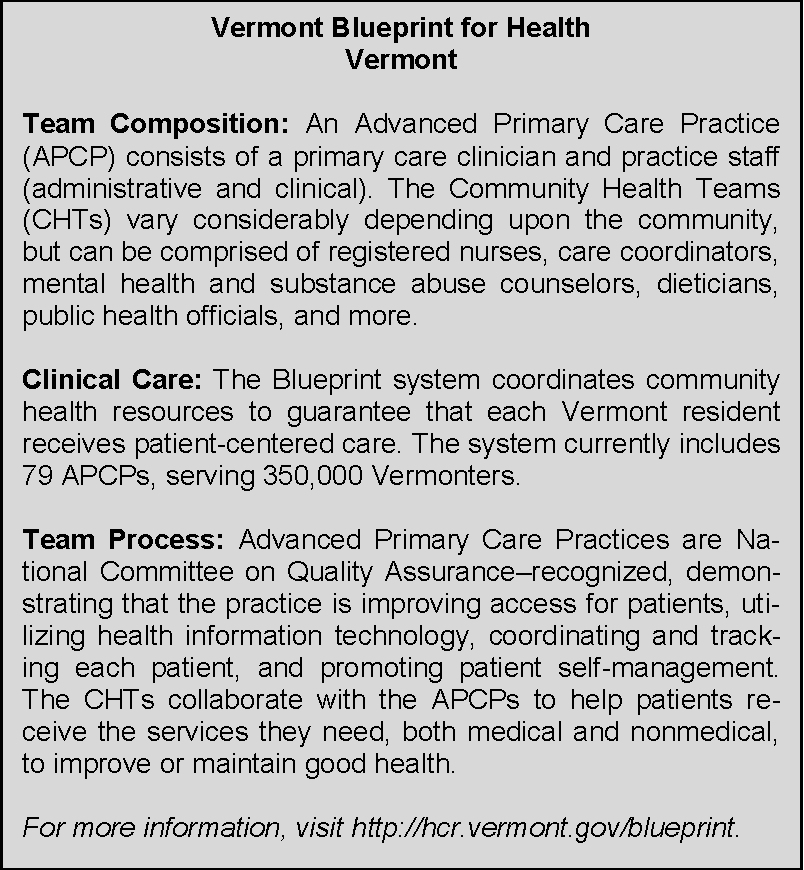

Measures for team-based health care fall into two categories: processes/outcomes and team functioning. The teams we interviewed considered three types of processes and outcomes: patient outcomes, patient care processes that lead to improved patient outcomes, and value outcomes. Improved patient outcomes provide one of the most important measures of any type of health care, and the number of validated measures has grown exponentially in recent years. The National Quality Measures Clearinghouse currently lists thousands of clinical quality measures from the National Quality Forum (NQF), the Ambulatory Care Alliance, the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement, the Joint Commission, the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA), health professional organizations, federal agencies, insurers, and many more. Patient outcome measures should and do vary between teams, reflecting the patients and populations served, as well as the unique strengths, challenges, and improvement initiatives of the team. For the hospital-based teams we interviewed, readmission to the hospital within 30 days was commonly cited as a relevant measure. Safety measures were also cited as important outcomes for patients. In some cases, teams track process measures that are linked to improved patient outcomes. The Vermont Blueprint for Health has adopted a comprehensive approach to patient outcomes by committing to achieve recognition of each of its Advanced Primary Care Practices as NCQA patient-centered medical homes, among other requirements. Finally, teams assess their outcomes by integrating quality and cost data. Increased capacity for delivering care, using the skillsets of diverse individuals in communicating effectively to the patient, caregivers, and the rest of the team, may decrease the cost of health care. [28] Leaders at MD Anderson have developed a framework for integrating information about the health outcomes of their patients with the costs of the care provided, resulting in a reproducible, trackable analysis of the value of their team care model. [39] The MD Anderson approach is illustrative of how the impact of a team can be measured. Currently, many measures that are tied to clinician performance refer to the work of a single clinician, typically a physician. [40] This perception of one individual’s accountability for clinical outcomes possibly undermines the effectiveness of the team, or, at least, does not provide an incentive to accelerate team-based care.

In addition to more traditional process and outcome measures, and reflecting a current national quality trend, all teams interviewed said that they measure satisfaction—formally or informally—of the patients and families they serve as well as that of the other team members. Satisfaction reflects the relational components of care, including rapport, respectful communication, and trust. It is unclear whether the patient and family’s perception of care is related to clinical effectiveness. Still, patient satisfaction is used as a proxy for, and if well-designed may truly reflect, patient-centeredness and patient engagement in care. Members of the team at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital say they know they have succeeded when, on the day of discharge, the patient and family say: “You’ve answered all my questions, covered all the bases, taken good care of me, and treated me like an equal. Thank you.” Similarly, a favorite informal measure of satisfaction mentioned by Hospice of the Bluegrass is public commemoration of the services provided by the hospice team in the patient’s obituary. Many teams we interviewed also emphasized the importance of measuring satisfaction among other team members as a way of tracking team function. The El Rio Community Health Center has implemented 360-degree evaluations which include measures of employee satisfaction. At the University of Pennsylvania, in addition to patient and cost outcomes, a critical measure of success is the satisfaction of team members, which is linked to staff retention—a critical element for team functioning. The Vermont Blueprint has a qualitative component to its evaluation, including focus groups, individual interviews, and a planned statewide implementation of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Patient-Centered Medical Home (CAHPS PCMH) survey in order to ascertain patient and practice experiences with team-based care.

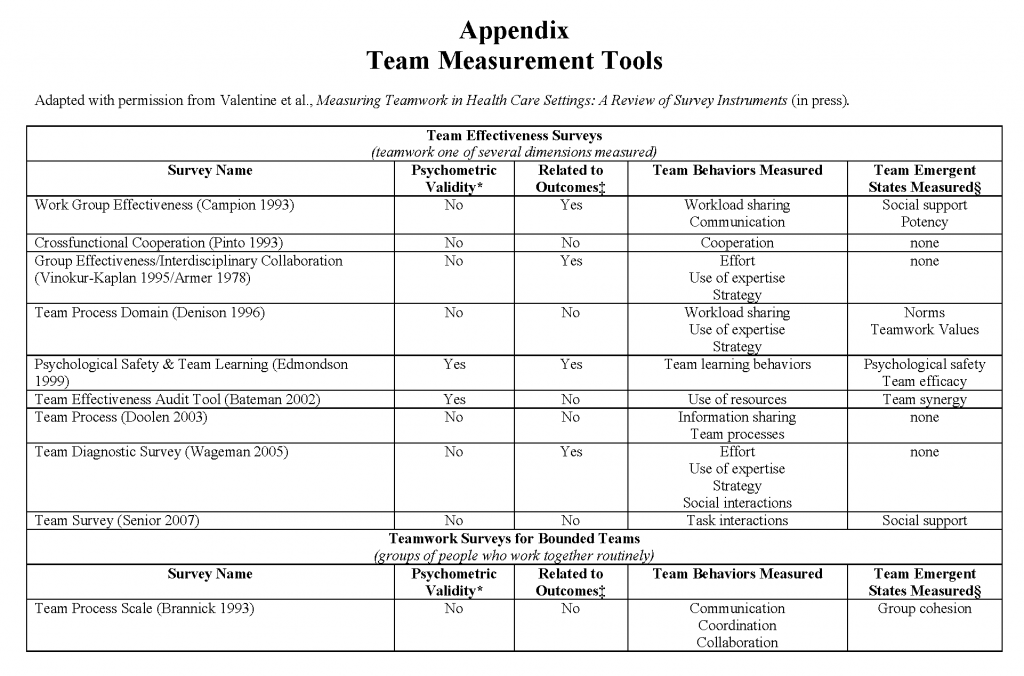

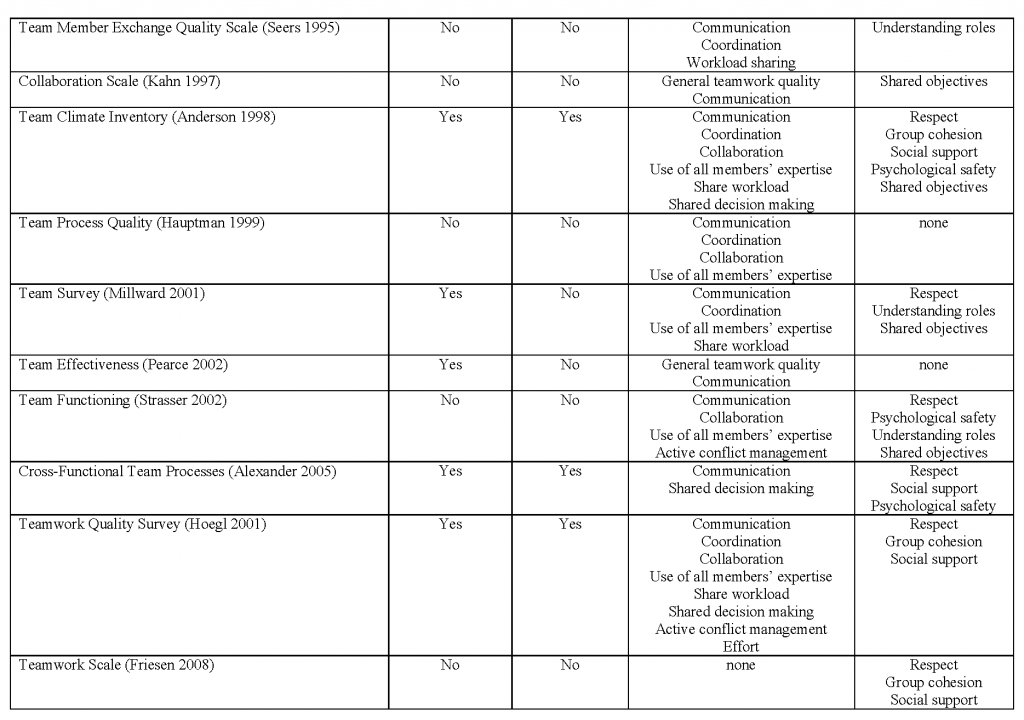

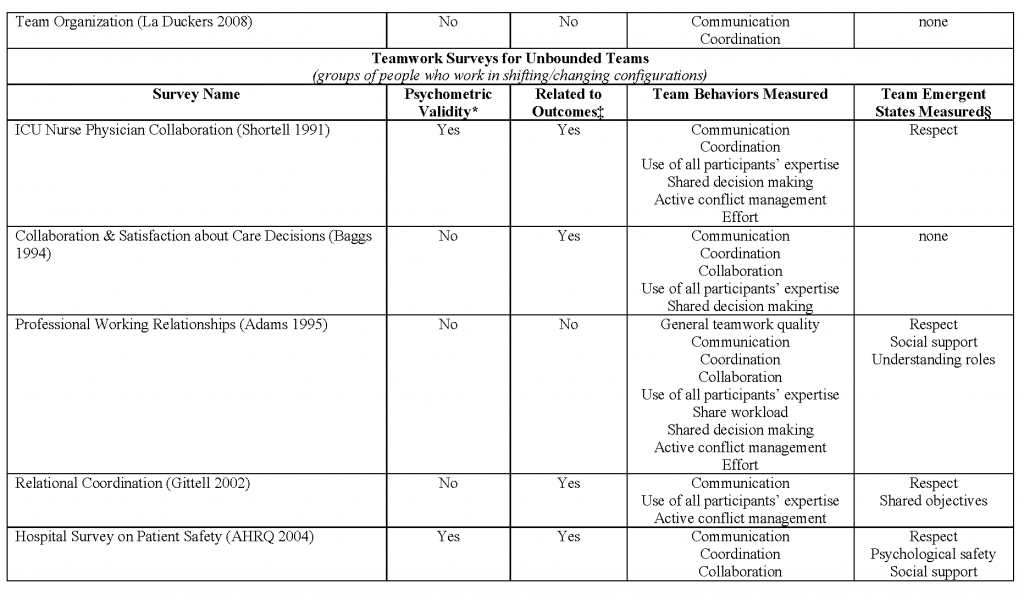

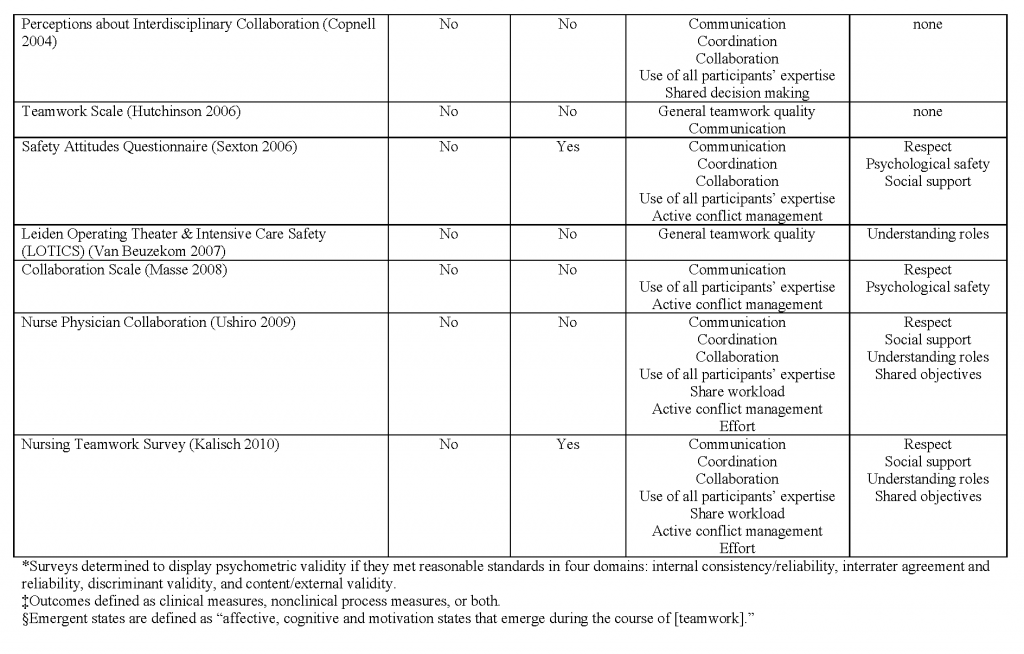

In addition to measuring the satisfaction of patients and other team members (which are indirect measures of team functioning), engaging in routine, frequent, meaningful evaluation of team function per se allows team members to improve their skills to fulfill the other principles of team-based care. A number of tools have been developed to directly assess the functionality of teams. Two measures mentioned by teams we interviewed include the Team Development Measure (teammeasure.org) and TeamSTEPPS questionnaires. Valentine and colleagues have produced a review of team measurement tools applicable to health care; a summary table of these tools, reproduced with permission, is available in the Appendix. [41] Despite the availability of team measurement tools, there is room for improvement in measurement of teamwork, since current measures look at various aspects of teamwork, few of them are robustly validated, and many are not routinely applied to teams in practice.

Organizational factors that support measurement to improve team function and outcomes include

- prioritizing continuous improvement in team function and outcomes and ensuring that electronic systems routinely provide data about the measures that matter to the teams providing care and can be immediately updated as indicated by frontline teams.

- developing routine protocols for measurement of team function, aimed at continuous improvement of the processes of team-based care.

- providing ample time, space, and support for team members to engage in meaningful evaluation of processes and outcomes together.

In summary, measurement of team-based care should include both measures of the processes and outcomes that derive from team functioning and measures of team functioning itself. There is a deficiency in the availability of validated measures with strong theoretical underpinnings for team-based health care. Improved measurement will enable teams to grow in their capacity to fulfill the principles, facilitate the spread, improve the research, and refine evaluation of the high-value elements of team-based care.

Implications of the Team-Based Health Care Principles and Values

To examine the implications of the principles and values of team-based health care outlined here, members of the Best Practices Innovation Collaborative met on February 28, 2012. Participants at the meeting provided feedback about the principles and values described here and considered the timeliness of the framework, including bridges to ongoing activities in related sectors. From those discussions, four themes emerged to guide the immediate activities of those working to accelerate high-value team-based health care:

- Ensuring that the patient and family are at the center of the team requires careful planning and execution.

- Targeting of team-based care—matching resources to patient and family needs—is essential to maximize value.

- Building bridges to ongoing activities related to team-based care is critical to ensure efficiency.

- Defining a coordinated research agenda for team-based care is necessary to achieve continuously improving, high-value team-based health care.

Making Patients and Families Active Members of the Team

The requirement that patients and families be at the center of care is espoused by most health care reform and improvement processes, including the patient-centered medical home, care coordination, interprofessional education, and more. Ensuring that patients and families are active members of the health care team is the next critical step toward high-value health care. Mitchell and colleagues describe a social compact between health professionals, patients, and society intended to strengthen the connections between patient-centered care and team-based care, with a call for patients to be active members of health care teams. [34] The codes of ethics of health professional societies have long argued that shared decision making is an ethical obligation, and that the legal and ethical notion of informed consent is built on the fundamental rights of patients to participate in decisions that affect their well-being. [42,43] Moreover, people who are involved in their own care have better health outcomes and typically make more cost-effective decisions. [44] In reality, the practice of putting patients and families on health care teams is daunting. Patients are often ill-prepared to participate on health care teams and health professionals are often ill-equipped to practice collaboratively with patients for many reasons—imbalance of power in relationships, poor communication, non-intuitive systems, payment structures that reward volume over value, lack of workforce preparation, and more. The solution to many of these problems requires restructuring the culture and practices of health care, including promoting transparency of information in an understandable fashion, orientation of people to health care team practices, predictability, and development and spread of readily-available tools for knowledge sharing, self-care, and patient-clinician–team communication. [37] There is also a role for measuring the performance of organizations in creating a practice environment that supports shared decision making. [45]

Targeting of Team-Based Care

High-quality team-based health care is costly to implement. As described by those we interviewed, teams are complex systems that require substantial investment to function at their highest capacity. Thus, the use of teams should be targeted to situations in which the transactional costs of team care are outweighed by the benefits in terms of health outcomes. Targeting is an ongoing process in which the needs of the patient and family are assessed repeatedly, with the expectation that needs are personal and will change over time and based on the situation. Health professionals must, as part of their professional responsibilities, ensure that assessments and reassessments are completed and call upon other health professionals and community services as indicated by patient/family needs. Figure 1 presents a schematic of the relationship between complexity of patient needs and the complexity of the corresponding team-based care. The exact composition of the team and services mobilized should be tailored according to patient/family needs and local resources.

Building Bridges to Activities Related to Team-Based Care

Team-based care and activities related to teams are increasing in many health care sectors. Building bridges between these activities can help ensure synergy and efficiency. Here, we highlight connections between team-based care and three areas in particular: interprofessional education and workforce development, health informatics, and care coordination.

Interprofessional Education

Health education groups in the United States and abroad have called for improved interprofessional education in the preclinical and clinical settings. A U.S. effort—the Interprofessional Education Collaborative—is led by a coalition of academic associations, foundations, and government agencies. In 2011 the group released a report on the core competencies of interprofessional education to stimulate effective team-based practice. These core competencies harmonize with the principles outlined in this paper and are critical for guiding the education, evaluation, and certification of health education programs and members of the modern health care workforce. We believe that the values and principles described in this paper supplement the core competencies and should be used to guide selection of candidates for the health professions, their training, their licensure and certification, and their ongoing evaluation by employers, patients, and society. Many team training tools currently exist in practice to help health professionals—and, ideally, patients and families—continue to develop and maintain values and skills to support their teamwork. One of the best-known programs, TeamSTEPPS, has recently expanded from the acute care to the ambulatory care setting.

Health Informatics and Technology

The explosion of digital capacity and stimulation of infrastructure development through policy have created opportunities for promotion and facilitation of team-based care. Health informatics has the capacity to support the work of teams (e.g., communication, process improvement, group training, shared work) while allowing required documentation within the regulatory and medico-legal environment. For example, an electronic health record designed with teams in mind can enable team charting, and informatics-driven simulation training systems can provide a safe, effective means of improving teamwork, particularly for rare or high-stakes situations. Furthermore, informatics can help teams make sense of vast amounts of data that can be captured to maximize continuous learning, monitor population health, and promote safety and quality without overwhelming team members.

High-functioning teams and their organizations must consider the transformative impact of Web-based, digital, and mobile technology on health and health care delivery. Technological innovations such as telehealth monitoring devices, behavior sensing mobile applications, and diagnostic tools on smartphones are already engaging patients and practitioners in new ways and expanding the continuum of care beyond traditional settings. The Internet is democratizing medical knowledge by providing unprecedented access to health-related content, research, and patient-to-patient communities such as CureTogether and PatientsLikeMe. The rapid emergence of innovative technologies, expanded access, and broad adoption is poised to disrupt how teams manage health and illness as well as how patient-centered care is delivered and received. [46]

Care Coordination

According to the NQF, “care coordination helps ensure a patient’s needs and preferences for care are understood, and that those needs and preferences are shared between providers, patients, and families as a patient moves from one health care setting to another. Care among many different providers must be well-coordinated to avoid waste, over-, under-, or misuse of prescribed medications, and conflicting plans of care.” [4,47] Additionally, the forthcoming IOM discussion paper “Communicating with Patients on Health Care Evidence” reports that 64 percent of people strongly agree (and 92 percent of people agree overall) that health care providers should work as a team to coordinate care and share health information. For patients with chronic conditions, 72 percent strongly agreed (and 97 percent agreed overall) that their care ought to be coordinated. These findings strongly support the conclusion that not only should care be coordinated to increase quality, but that patients already expect to receive coordinated care. [48]

Reviewing the myriad activities in the area of care coordination is beyond the scope of this paper; however, the links between team-based care and care coordination are clear. For example, care coordination starts with a written plan of care; team-based care requires an explicit statement of shared goals. These are integrally related activities; the patient’s goals should drive the development of the patient’s care plan. Fundamentally, we see the principles and values of high-functioning team-based care as central to the success—both in terms of efficiency and effectiveness—of care coordination. The NQF publication Preferred Practices and Performance Measures for Measuring and Reporting Care Coordination: A Consensus Report (2010) outlines many of the specific steps that can help patients and clinicians achieve the principles of effective team-based care within the context of practicing care coordination. Many of the NQF-endorsed preferred practices are applicable to all settings in which team-based care is employed [49].

Defining a Research Agenda

To date, research on team-based care has largely focused on describing the successful elements of individual programs. Comparisons of team-based care programs and paradigms have been hampered by lack of common definitions, shared conceptualization of components, and a clear research agenda. The bulk of this paper attempts to frame the first two elements. Here, we outline suggestions for an approach to the third element—the research agenda. We suggest that the research agenda be divided into two broad categories: targeting team-based care and sustaining effective team-based care.

The first main purpose of research about team-based care is to determine the specific practices that achieve the best outcomes and cost savings for particular patients in a given setting. Simply stated, the research agenda should aim to perfect the science of targeting team-based care. The elements of team-based care to be studied include the who (team composition and roles), what (services provided), where (health care setting, home or community environment, transition between settings), and how (teamwork model employed, including methods of communication, conflict resolution, etc). The measured outcomes should be meaningful to patients and should include improved personal and community health, reduced costs, and the comparative effectiveness of team-based care elements for particular patients in particular settings.

As the science of targeting team-based care is perfected, the second purpose of the research agenda must be to consider elements critical to sustaining targeted team-based care. Areas for consideration include engagement of patients and families (what are the most effective and efficient ways to help patients and families become active participants in their care and as members of the team—including the role of personal technologies and informatics?); the health care workforce (how are the right people selected and trained?); practical tools for team-based care implementation and assessment (how can tools be matched to local needs and uptake of high-quality tools be promoted?); and more.

Summary

In conclusion, accelerating the implementation of effective team-based health care is possible using common touchstone principles and values that can be measured, compared, learned, and replicated. This paper provides guidance about the personal values and core principles of high-performing teams as well as the organizational support that is required to establish and sustain effective team-based care. Teams hold the potential to improve the value of health care, but to capture the full potential of team-based care, institutions, organizations, governments, and individuals must invest in the people and processes that lead to improved outcomes. To target expenditures and plan wisely for outcome-oriented team-based care, the top priorities should be the targeting of team-based care to situations in which it promotes the most efficiency and effectiveness and patient engagement (including shared decision making). Given the enthusiasm and activity in team-based care present today, immediate and deep investment in these areas holds profound potential for transformative change in U.S. health care.

References

- Grumbach, K., and T. Bodenheimer. 2004. Can health care teams improve primary care practice? JAMA 291(10):1246-1251. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.10.1246.

- Gawande, A. 2011. Cowboys and Pit Crews. Harvard Medical School Commencement Address. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/cowboys-and-pit-crews (accessed May 14, 2020).

- Institute of Medicine. 2011. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13058.

- Bodenheimer, T. 2008. Coordinating care—a perilous journey through the health care system. New England Journal of Medicine 358(10):1064-1071. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165

- Pham, H. H., D. Schrag, A. S. O’Malley, B. Wu, and P. B. Bach. 2007. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. New England Journal of Medicine 356(11):1130-1139. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa063979

- Pham, H. H., A. S. O’Malley, P. B. Bach, C. Saiontz-Martinez, and D. Schrag. 2009. Primary care physicians’ links to other physicians through Medicare patients: the scope of care coordination. Annals of Internal Medicine 150(4):236-242. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-4-200902170-00004.

- Barnett, M. L., N. A. Christakis, J. O’Malley, J. P. Onnela, N. L. Keating, and B. E. Landon. 2012. Physician patient-sharing networks and the cost and intensity of care in US hospitals. Medical Care 50(2):152-160. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31822dcef7

- Petersen, L. A., T. A. Brennan, A. C. O’Neil, E. F. Cook, and T. H. Lee. 1994. Does house staff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events? Annals of Internal Medicine 121(11):866-872. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-121-11-199412010-00008

- Horwitz, L. I., T. Moin, H. M. Krumholz, L. Wang, and E. H. Bradley. 2008. Consequences of inadequate sign-out for patient care. Archives of Internal Medicine 168(16):1755-1760. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.16.1755

- Williams, R. G., R. Silverman, C. Schwind, J. B. Fortune, J. Sutyak, K. D. Horvath, E. G. Van Eaton, G. Azzie, J. R. Potts III, M. Boehler, and G. L. Dunnington. 2007. Surgeon information transfer and communication: factors affecting quality and efficiency of inpatient care. Annals of Surgery 245(2):159-169. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000242709.28760.56

- The Joint Commission. 2004. Sentinel event alert: Preventing infant death and injury during delivery. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/en/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sentinel-event-alert-newsletters/sentinel-event-alert-issue-30-preventing-infant-death-and-injury-during-delivery/ (accessed May 14, 2020).

- Gawande, A. A., M. J. Zinner, D. M. Studdert, and T. A. Brennan. 2003. Analysis of errors reported by surgeons at three teaching hospitals. Surgery 133(6):614-621. https://doi.org/10.1067/msy.2003.169

- Institute of Medicine. 2010. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12750

- Audet, A. M., K. Davis, and S. C. Schoenbaum. 2006. Adoption of patient-centered care practices by physicians: Results from a national survey. Archives of Internal Medicine 166(7):754-759. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.7.754

- Famadas, J. C., K. D. Frick, Z. R. Haydar, D. Nicewander, D. Ballard, and C. Boult. 2008. The effects of interdisciplinary outpatient geriatrics on the use, costs and quality of health services in the fee-for-service environment. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 20(6):556-561. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03324884

- Boult, C., A. F. Green, L. B. Boult, J. T. Pacala, C. Snyder, and B. Leff. 2009. Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: Evidence for the Institute of Medicine’s Retooling for an Aging America report. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57(12):2328-2337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02571.x

- Institute of Medicine. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10027

- Pew Health Professions Commission. 1995. Critical challenges: Revitalizing the health professions for the twenty-first century. San Francisco: UCSF Center for the Health Professions. Available at: https://healthforce.ucsf.edu/publications/critical-challenges-revitalizing-health-professions-twenty-first-century

- AAFP, AAP, ACP, AOA. 2007. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. Washington, DC. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMHJoint.pdf (accessed May 14, 2020).

- Bodenheimer, T. 2011. Lessons from the trenches—a high-functioning primary care clinic. New England Journal of Medicine 365(1):5-8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1104942

- Bodenheimer, T., and B. Y. Laing. 2007. The teamlet model of primary care. Annals of Family Medicine 5(5):457-461. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.731

- Mui, A. C. 2001. The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE): An innovative long-term care model in the United States. Journal of Aging & Social Policy 13(2-3):53-67. https://doi.org/10.1300/j031v13n02_05

- Naylor, M. D. 2004. Transitional care for older adults: A cost-effective model. LDI Issue Brief 9(6):1-4.

- Porter, M. E., and E. O. Teisberg. 2007. How physicians can change the future of health care. JAMA 297(10):1103-1111. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.10.1103

- Jones, D. A., M. A. DeVita, and R. Bellomo. 2011. Rapid-response teams. New England Journal of Medicine 365(2):139-146. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0910926

- Wagner, E. H., B. T. Austin, C. Davis, M. Hindmarsh, J. Schaefer, and A. Bonomi. 2001. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Affairs 20(6):64-78. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64

- Wittenberg-Lyles, E. M., and D. P. Oliver. 2007. The power of interdisciplinary collaboration in hospice. Progress in Palliative Care 15(1):6-12. https://doi.org/10.1179/096992607X177764

- Naylor, M. D., K. D. Coburn, E. T. Kurtzman, et al. Inter-professional team-based primary care for chronically ill adults: State of the science. Unpublished white paper presented at the ABIM Foundation meeting to Advance Team-Based Care for the Chronically Ill in Ambulatory Settings. Philadelphia, PA; March 24-25, 2010.

- Boon, H., M. Verhoef, D. O’Hara, and B. Findlay. 2004. From parallel practice to integrative health care: a conceptual framework. BMC Health Services Research 4(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-4-15

- Bodenheimer, T. 2007. Building teams in primary care: Lessons learned. San Francisco: California HealthCare Foundation. Available at: https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PDF-BuildingTeamsInPrimaryCareLessons.pdf (accessed May 14, 2020).