Payment Reform for Better Value and Medical Innovation

Introduction

Over the past 50-60 years, biomedical science and technology in the United States have advanced at a remarkable pace, allowing Americans to live longer, healthier lives. And while we have gained tremendous benefit from continuous medical innovation, health care delivery has simultaneously become more complex, expensive, and, in some ways, less patient-centric (IOM, 2001). In 2015, US health care spending grew 5.8%, totaling $3.2 trillion or close to 18% of GDP (CMS, 2016a), and it has been estimated that upwards of 30% of health expenditures may not contribute to health improvement (IOM, 2013). In tandem, health indicators and outcomes in the US are lagging, including measures of access, efficiency, equity, and quality (IOM and NRC, 2013). And while these trends could be attributed to myriad factors, ultimately, how we pay for care strongly influences how care is delivered (IOM, 2013). With fee-for-service (FFS)—the longstanding, traditional payment model used in the U.S.—health care services are paid for individually and aggregate payment is driven by the volume of services rendered. In an effort to reign in health care costs, increase clinical efficiency, encourage greater coordination among providers to better meet the needs of patients, and provide value for true engagement of patients’ and family members’ care decisions, payment reform efforts are focusing on value-based models of care delivery. These models aim to incentivize providers to keep their patients healthy, and to treat those with acute or chronic conditions with cost-effective, evidence-based treatments.

Value-based payment strives to promote the best care at the lowest cost, allowing patients to receive higher-value, higher quality care. Payment reform, with the goals of shifting provider payments and incentives from volume to value, is a health policy issue that has bipartisan support. Consistent with these goals and building on early, successful payment reform models carried out in the public and private sectors (Abrams et al., 2015), provisions contained in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) set in motion several initiatives that seek to reform how health care is paid for and delivered more broadly. Through these provisions, the law uses a multi-pronged approach to instituting reforms, focusing on: testing new payment and care delivery models that aim to increase care coordination, quality, and efficiency (e.g. patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations); shifting the provider reimbursement system orientation to outcomes rather than services; and investing in methods to improve health system efficiency, such as issuing grants to establish community health teams to support a medical home model (Abrams et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2010).

Payment and delivery reform, alongside related legislative and regulatory changes, has the potential to make transformative models of health care delivery more sustainable, with the promise of better outcomes, lower costs, and more support for investment in new treatments that are truly valuable. Simultaneously, the potential for medical innovations to improve the patient care experience, produce better health outcomes, and reduce health cost seems greater than ever. This includes new treatments for unmet needs, new cures, innovations in digital health, much larger data analytics, and team-based care that is much more prevention-oriented, convenient and personalized. As with most transformative change, transitioning to value-based models of care delivery and payment has been met with some challenges. While payment reforms have shown some promising results, overall impacts on spending trends have been modest and critical obstacles remain to successful implementation, including inadequate performance measures, regulatory barriers, insufficient evidence on successful models, and limited knowledge of the competencies required for providers to succeed within this new paradigm. Policymakers will need to address and mitigate these and other challenges as they chart the next steps of payment reform. This discussion paper seeks to highlight payment reform initiatives underway, underscore pressing challenges in need of attention, and provide recommended vital directions to advance reform and better ensure its success.

Payment Reform Initiatives and Stakeholder Contributions

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s Pilot Initiatives

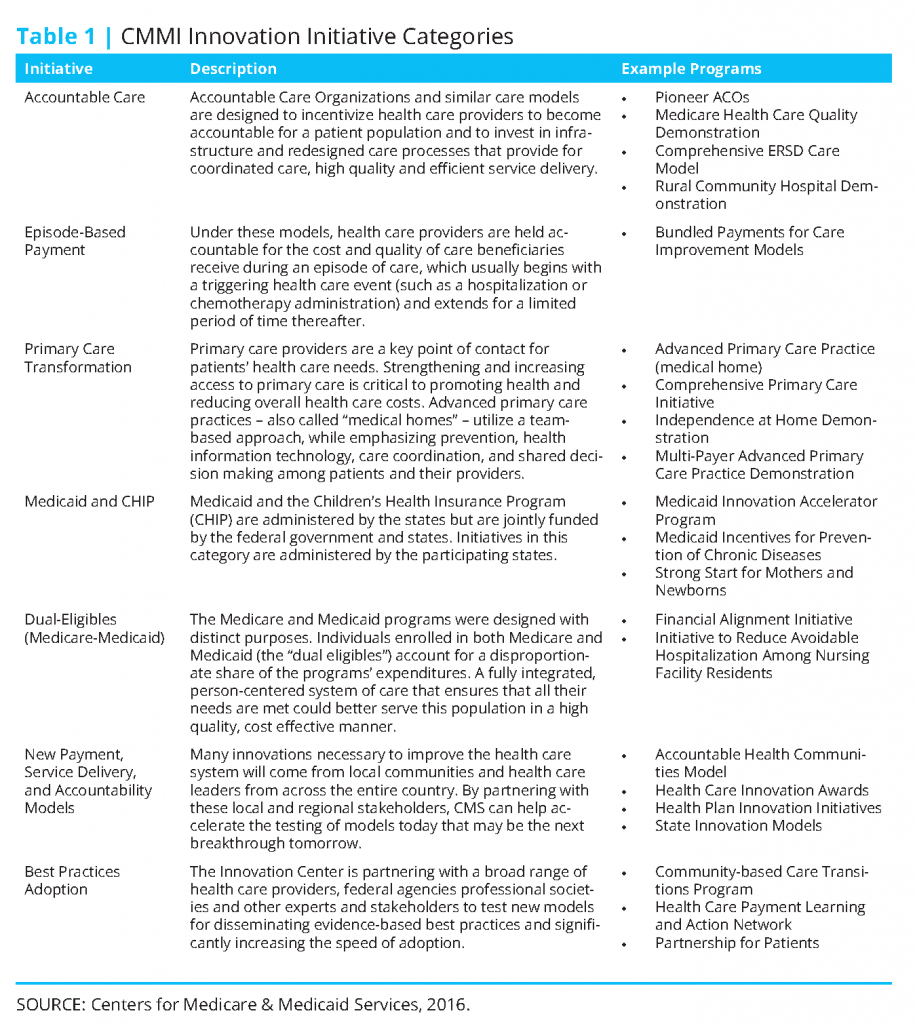

Among the most significant of the payment reform provisions contained in the ACA is the creation of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI or “Innovation Center”) within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which went into effect in 2011. The Innovation Center was established to identify, develop, assess, support, and spread new payment and delivery models that hold significant promise for lowering expenditures under Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), while simultaneously improving or maintaining quality of care delivered (Berenson and Cafarella, 2012; Abrams et al., 2015). The law authorizes the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to spread successful CMMIsupported payment innovations, if sufficient evidence exists demonstrating reduced costs and improved outcomes (Guterman et al., 2010). The law appropriates $10 billion to the Innovation Center every ten years; CMMI received the first $10 billion for 2011-2019 to execute pilot programs initiated during this time. The law identified several priorities and existing models that CMMI ought to consider in constructing its pilots, emphasizing reforms to promote care coordination, encourage efficient and high-quality care, and improve patient safety. The Innovation Center organizes its innovation models into seven categories (Table 1). Currently, CMMI has 33 ongoing pilot initiatives across these categories, and another 25 initiatives under development, announced, or just getting started (CMS, 2016b).

Patient-centered medical homes (medical homes), accountable care organizations (ACOs), and bundled payments are among the most commonly cited and discussed alternative payment models. A medical home is a model that provides care that is comprehensive, patient-centered, coordinated and team-based, accessible, quality and safe (AHRQ, 2016). Medical home models rely heavily on a primary care practice to deliver and coordinate the majority of care for the beneficiary. An accountable care organization is a group of health care providers, such as doctors, hospitals, health plans, who voluntarily come together to provide coordinated, high-quality care to populations of patients, and agree to assume responsibility for the quality and costs of care provided. To encourage the formation of ACOs, the ACA established the Medicare Shared Savings Program, whereby participating ACOs could keep half of the resulting savings if they met the quality benchmarks established and kept costs below budget. ACOs could also enter into a “two-sided risk” model—with potential shared savings of up to 60%, if total savings exceed the minimum savings rate—which would require the ACO to pay for a portion of the losses if spending were to go beyond the established budget. While participation in the Shared Savings Program exceeded expectations, overall performance results have been mixed (Abrams et al., 2015). Finally, a bundled payment reimburses the provider(s) in a single payment for all the services required to treat a specific condition or provide a specific treatment over a defined period of time. Bundled payments incentivize providers to come in below budget for a given care episode.

HHS’ Historic Shift to Alternative Payment Models

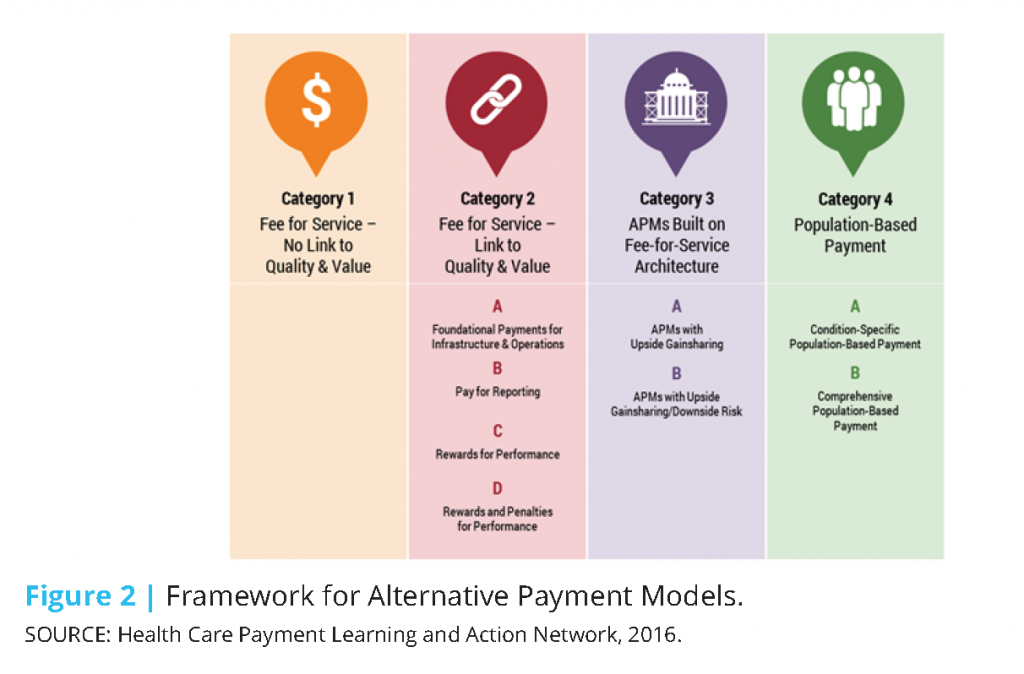

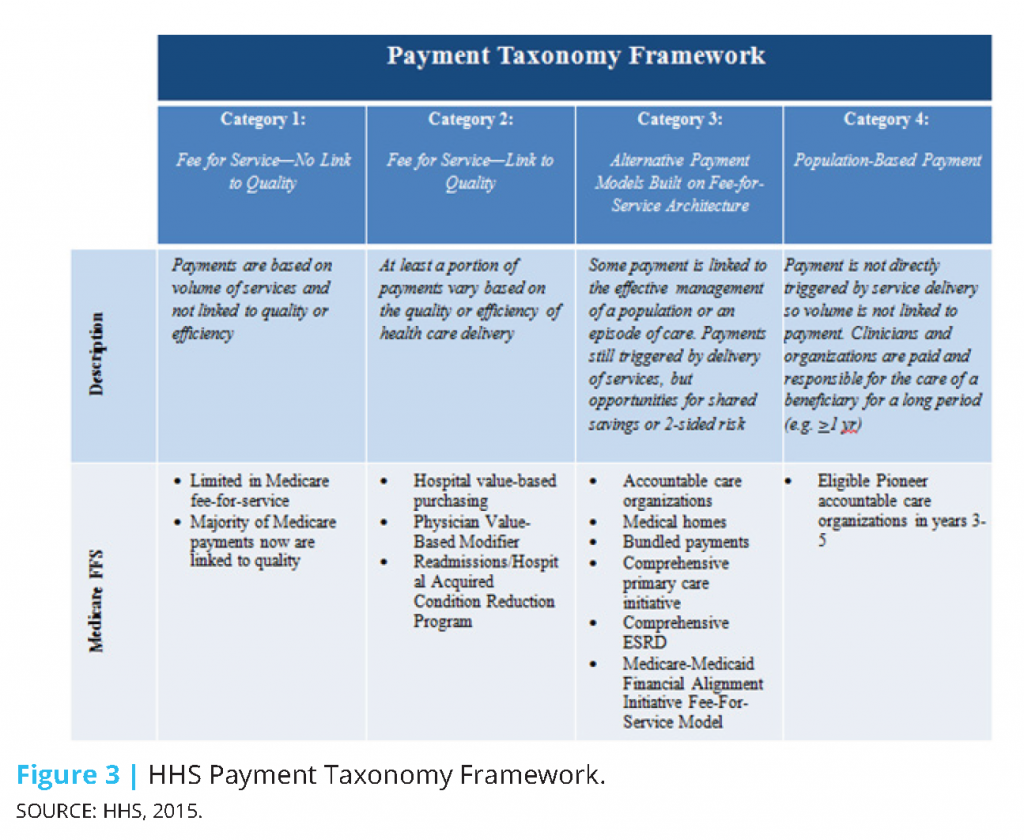

In January 2015, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) made a historic announcement, setting a timeline with specific, measurable goals to shift Medicare and the greater health care system toward reimbursing providers through alternative payment models (APMs) (HHS, 2015). In setting its goals, HHS adopted a framework categorizing health care payment models based on how providers receive payment for the care they provide (CMS, 2015):

- Category 1: Fee-for-service with no link of payment to quality

- Category 2: Fee-for-service with a link of payment to quality

- Category 3: Alternative payment models built on fee-for-service architecture

- Category 4: Population-based payment

Value-based payments are considered those falling within categories 2-4. Based on the framework, moving from category 1 to category 4 would necessitate both increased accountability for quality and total cost of care, and shifting focus toward population health management.

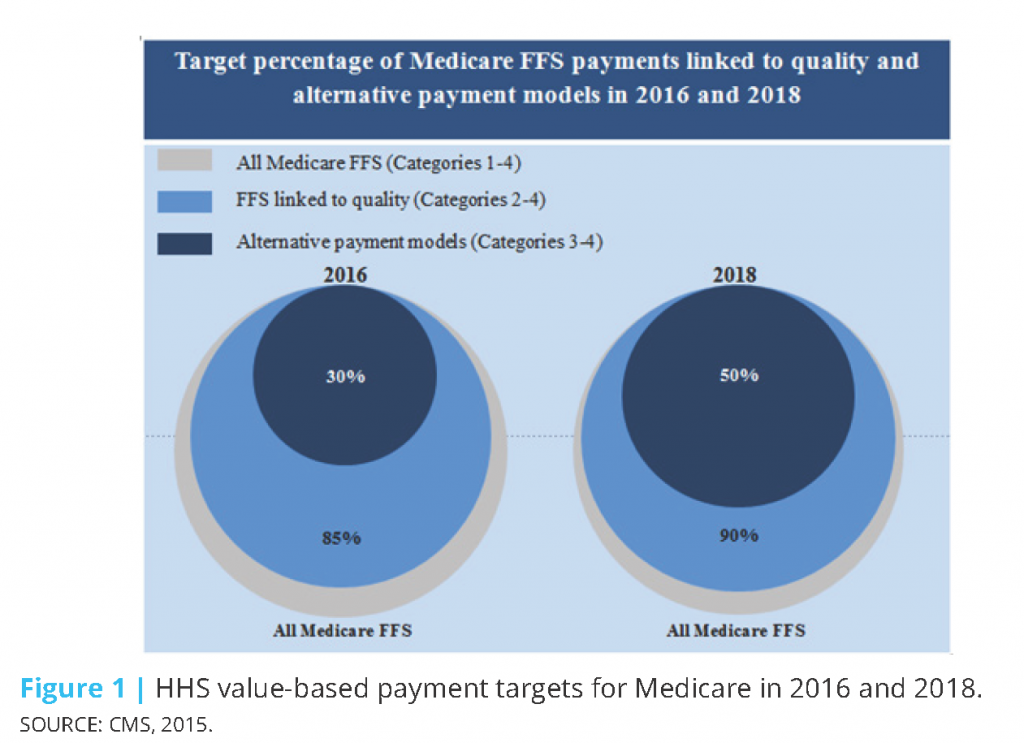

In 2015, HHS set the goal of tying 30% of traditional (fee-for-service) Medicare payments to APMs (categories 3 and 4) by the end of 2016, and tying 50% of payments to APMs by the end of 2018 (CMS, 2015). HHS also set goals of tying 85% of all traditional Medicare payments to quality or value (categories 2-4) by 2016 and 90% by 2018 through programs such as the Hospital Value Based Purchasing and Hospital Readmissions Reduction Programs (Figure 1). In 2011, while over half of Medicare payments were linked to quality, practically none were in alternative payment models. By March 2016, almost a year ahead of schedule, the 2016 goals were met with 30% of Medicare payments tied to alternative payment models and 85% tied to quality. CMS continues to move toward meeting its 2018 goals.

To facilitate the scale and spread of these goals beyond Medicare, HHS created the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (LAN) to align stakeholders across sectors and accelerate the transition to value-based payment. Through the LAN, HHS works with private payers, employers, consumers, providers, states and state Medicaid programs, and other partners to adopt and expand APMs into their programs. Consistent with the goals set for Medicare, the LAN seeks to facilitate tying 30% of payments to APMs by 2016 and 50% by 2018 across the health care system. As part of their efforts, the LAN convened a work group to build on HHS’ framework for categorizing and measuring APMs. The framework developed (Figure 2) expands upon that originally developed by HHS (Figure 3) and includes 4 primary categories and 8 subcategories. The framework rests on seven principles identified by the workgroup (HCPLAN, 2016):

- Patients must be empowered as partners in health care transformation; changing providers’ financial incentives is not sufficient to achieve person-centered care.

- Health care spending must shift significantly towards population-based, more person-focused payments.

- Value-based incentives should ideally reach the providers that deliver care.

- Payment models that do not take quality into account are not considered APMs in the APM Framework, and do not count as progress toward payment reform.

- Value-based incentives should be intense enough to motivate providers to invest in and adopt new approaches to care delivery.

- APMs will be classified according to the dominant form of payment when more than one type of payment is used.

- Centers of excellence, accountable care organizations, and patient-centered medical homes are examples of delivery systems, rather than categories, in the APM Framework.

Alongside the efforts of the LAN, many private organizations and industry consortia have set specific goals to transition to new payment models. The Health Care Transformation Task Force is an example of an industry consortium seeking to align and convene stakeholders across the private and public sectors to accelerate the adoption of value-based care. The Task Force brings together patient, payer, provider, and purchaser groups to collaborate and work together to make system transformation possible. Payer and provider members in the Task Force commit to have 75% of their businesses utilizing value-based payment arrangements by January 2020. Purchaser and patient members commit to building and maintaining the necessary demand, support, and education of their communities to achieve this target (HCTTF, 2016).

Employer-Led Initiatives and Innovations

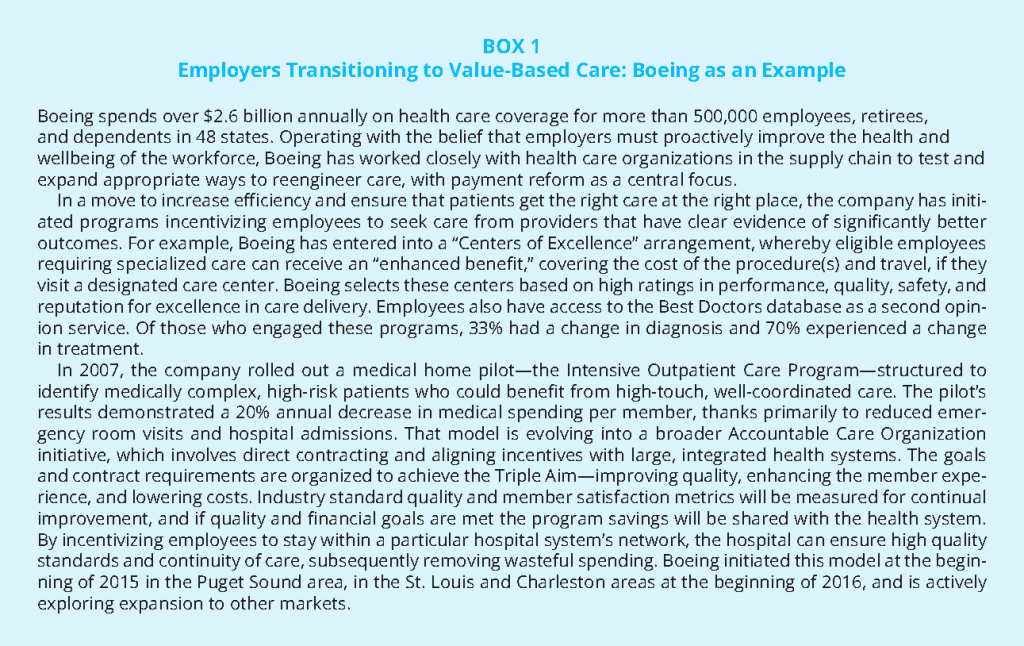

Nearly half of people with health insurance in the US receive their coverage through an employer (KFF, 2015). As the costs of health care have risen, so too have the financial burdens on the employers providing coverage. While some employers have responded by reducing or eliminating coverage, others have increased their involvement in efforts and initiatives that seek to curb costs and improve care quality (Schilling, 2011). Although employers have long been involved in efforts and initiatives to improve health care quality, overall, most payment reform efforts have not been spearheaded by employers (AcademyHealth et al., 2013). Many small to mid-size organizations often lack the needed number of employees and/or critical competencies to drive these initiatives. Larger employers, however, with the sophistication and resources to influence change, have been capable of driving advancement in this space, often in partnership with providers. The payment reform experience of Boeing illustrates these trends (Box 1). Boeing has worked closely with health care organizations to test and expand appropriate ways to reengineer care, with payment reform as a central focus. To increase efficiency and ensure that patients get the right care at the right place, the company has initiated programs incentivizing employees to seek care from providers that have clear evidence of significantly better outcomes, and has aligned with providers committed to improving quality, enhancing the member experience, and lowering costs.

Traditionally, by participating in self-funded plans, large employers have assumed most of the insurance risk and thus cost of care for how the system performs, but have had very little control over how health care is delivered. In recent years, however, employers have been “doubling down on opportunities to impact health care quality and costs at the source – by working more closely with high performing providers through select networks and providing better information to help employees make higher-value health care choices” (Hoo and Lansky, 2016). In a 2014 Aon Hewitt Health Care survey of over 1200 medium to large employers, 65% of companies identified moving toward provider payment models that strive for “cost-effective, high-quality” outcomes as a key strategic direction going forward (Aon Hewitt, 2014). Employers are hopeful that as financial risk becomes shifted to providers, increased innovation and competition will ultimately lead to overall reduced costs and better health outcomes for beneficiaries. And, when risk is shared jointly among groups of providers, providers will be more likely to deliver coordinated, integrated care.

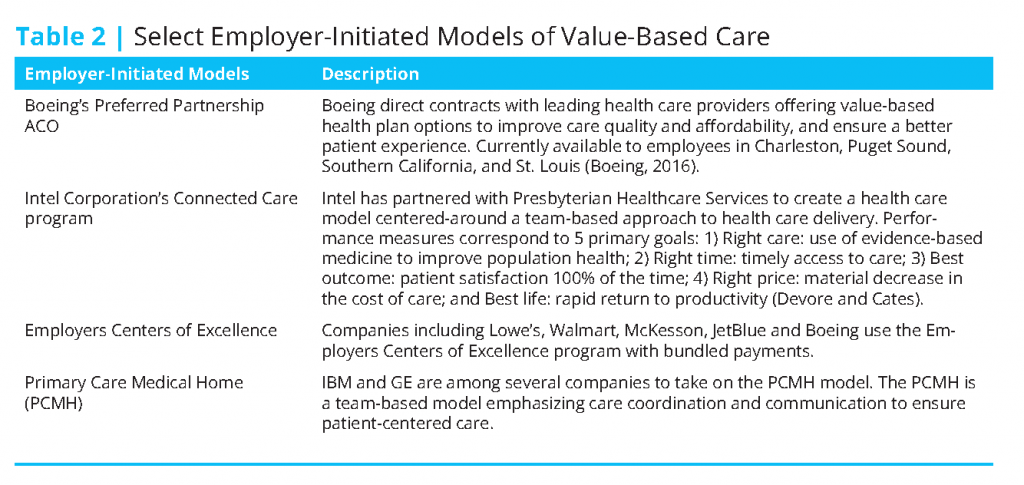

As the system transitions, employers are increasingly participating in and/or developing innovative, value-based approaches to delivering patient-centered, lower-cost, quality health care. In fact, more and more, employers are partnering with providers to build high-performance networks of their own through ACOs, medical homes, and centers of excellence (Table 2) (Hoo and Lansky, 2016).

Insurer-Led Initiatives and Innovations

As the health care system transitions from a fee-for-service to value-based approach, insurers are playing an important role in advancing innovative alternative payment models and approaches. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts’ (BCBSMA) payment reform initiative, the Alternative Quality Contract (AQC) has been recognized for developing new and effective partnerships with its members and providers. The AQC seeks to reduce costs while improving quality and health outcomes by using both payment incentives as well as provider support tools. The model rests on a few core elements: a global budget structure; a significant performance incentive system; long-term contract assurance (3-5 years) between BCBSMA and providers with fixed spending and quality targets; and clinical and information support, including group-specific reporting and analysis on spending and quality performance, as well as educational and best-practice sharing forums (Seidman et al., 2015). The AQC has a quality measurement system that includes 64 measures (such as clinical performance and outcomes, patient experience), each of which has a range of “performance gates” to score and reward quality care. This performance score is not only tied to provider payment, but also to the provider’s share of budget surplus and/or deficit. For example, with a higher quality score, a provider will get to keep more of the budget surplus and have to pay less of the deficit owed. Overall, the AQC model has been shown to be effective at improving health outcomes and quality, while reducing costs (Seidman et al., 2015; McKesson, 2016). AQC’s success has been attributed to a combination of its robust incentives structure, as well as commitment to transparent sharing of data and best practices with its providers.

BCBSMA’s AQC is a good case example of the ways in which payers are advancing payment reform models and initiatives. It offers several best practices for insurers to drive and/or promote successful transformation. In 2015, Avalere examined BCBSMA’s experience with the AQC and identified a series of observations related to the important role payers play in advancing alternative payment models and approaches (Seidman et al., 2015):

- Payment reform programs can significantly change provider behavior: if designed well, models can reduce costs and enable better quality care across providers.

- Changing behavior requires providers to have “skin in the game,” but payers need to meet providers where they are today: effective and meaningful incentive schemes need to be in place to realize the desired behavior.

- New payment models should hold providers accountable for the full range of patient care costs: full accountability promotes care coordination, efficiency, and controlled spending.

- Providers can implement meaningful change, but need time, consistent goals, and a similar commitment from payers to do so: provider transformation requires time, support, and commitment from payers.

- Providers need detailed spending and quality information and clinical support to take on risk: transparency and access to data and care redesign support from payers are critical as providers assume more financial risk.

- Payers with significant local presence are best positioned to implement innovative payment models: payers with greater market share are more apt to have the resources and ability to achieve provider buy-in.

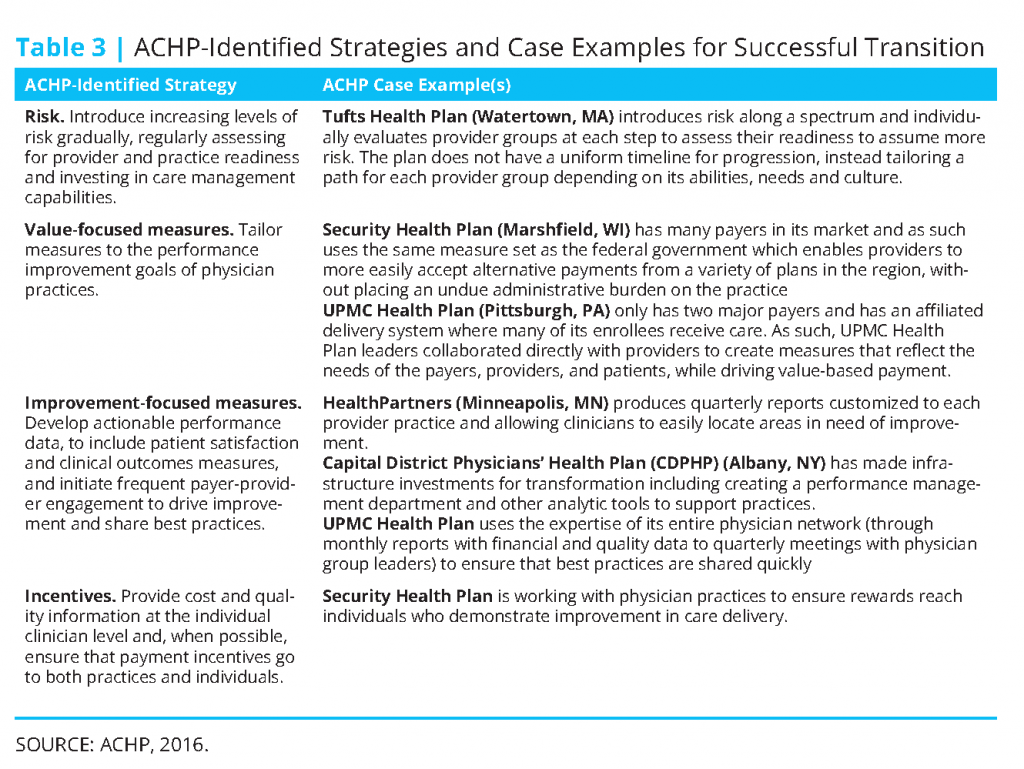

Much like the observations identified by Avalere, the Alliance of Community Health Plans (ACHP) has identified a series of strategies, best practices, and related case examples for ensuring the success of innovative payment and delivery models (ACHP, 2016) (see Table 3). A few of the case examples noted are provider-sponsored plans, which have been growing in number as physician groups, health systems, and hospitals seek to reduce costs, improve care quality, and better meet the needs of the communities they serve.

Engaging Patients in Delivery and Payment Reform Initiatives

Methods to most effectively engage consumers in payment reform discussions are still evolving—partially due to the fact that the intricacies of payment reform can be largely foreign to the average health care consumer. Notably, the direct effect of alternative payment models on patients can be said to be variable (Delbanco, 2015). In the context of pay for performance, patients may not notice any discernable difference in their care. In ACO or medical home settings, however, there may in fact be a noticeable difference in the patient’s care experience (Delbanco, 2015). In fact, research has been conducted indicating that, in these settings, patients recognized improvements in their care coordination and were overall more satisfied with their care (Miller, 2014). In focus group research conducted by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, focus group participants indicated that consumers (generally speaking) were not that interested in learning about the provider reimbursement process, and were uncomfortable with the idea that payment is linked to their health and health care (AF4Q, 2011). Participants indicated that consumers do want enhanced quality from the health care system, including better primary care and coordination. Depending on the payment reform model, patients may desire and have use for varying levels of information.

Engaging consumers and consumer advocates in advancing payment reform innovations is important to driving progress. Involving consumers, caregivers and their advocates in the process better assures that new models or approaches will actually have the intended effects of bettering the patient experience, improving outcomes, safety and quality, and controlling costs. Several hospitals and health systems, including the MCG Health System in Georgia and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Massachusetts, have made deliberate efforts to deliver care in this way since the mid-1990s (AHA, 2005).

Today, continued efforts are underway to better engage consumers and their advocates in the design and delivery of care to best meet their needs. The activities of several organizations are developing efforts to help consumer advocates address health care and cost issues, such as the Healthcare Value Hub, created by Consumers Union. And, in an effort to engage patients and their families directly, Patient and Family Advisory Councils offer a model of engagement that has been used in delivery and payment reform discussions. These councils serve as an advisory resource, bringing together patients, their families, and members of the health care team to improve the experience of the patient and their family. The role of the council is to promote improved relationships, provide a venue for information sharing, and facilitate communication and coordination between patients, families, and the care team, all of which serves to actively involve patients and their families in the care design and delivery process (IPFCC, 2002). RWJF Aligning Forces for Quality communities in Humboldt County, CA, Maine, and Oregon employed and had successes with these advisory councils during payment reform discussions (AF4Q, 2014).

Challenges and Barriers to Payment Reform

While clear progress has been made in promoting payment innovation, by the federal and state governments, as well as stakeholder-led initiatives and innovations, there remain critical challenges to successful implementation. Among these challenges include: aligning multiple, heterogeneous payer profiles; identifying the necessary provider competencies for success; developing robust performance measures; navigating regulatory and legal barriers; and accessing data and evidence on successful models.

Participation and Alignment of Multiple Payers

Broad payer participation and alignment are critical for providers to commit to the delivery of value-based care and for payment reform to be successful. Across the country, providers (physicians, hospitals, etc.) are reimbursed by multiple payers, ranging from the major public payers—Medicare and Medicaid—to numerous commercial insurance companies, and also self-pay individuals. Individual payers use differing and sometimes multiple approaches to pay for health care. This variation, combined with the differing strategies among payers as they undertake transition from fee-for-service to value-based care, underlies the substantial complexity in the marketplace. In the presence of multiple payers, there exists an incentive for any given payer to refrain from adopting alternative payment models, while still recouping savings required of providers working under payment reform approaches implemented by other payers (Miller, 2014). Further, initial provider responses to payer constraints may not necessarily yield care delivered in a value-based way. For providers to truly transform the way they deliver care, critical financial incentives need to be in place, and will only be possible if a sufficient number of payers—beyond Medicare and Medicaid—support and implement payment reform (Rajkumar et al., 2014). For payment reform to be successful, all payers need to change their payment systems in similar ways (IOM, 2010), such that they have common incentives, measurement and quality improvement goals (McGinnis and Newman, 2014).

Limited Experience and Knowledge About How to Succeed in New Payment Models

While alternative payment models have demonstrated some promising outcomes, early performance has been mixed overall; reductions in spending and improvements in quality have been modest, although still meaningful (McWilliams et al., 2016). While these early findings have highlighted an important need to improve model design, they have also underscored an important issue, which is that many providers (including physician practices and hospitals) do not know how to effectively engage and succeed in alternative payment models to improve care quality and outcomes, and reduce costs. The resource and skill challenges facing providers include: the lack of sufficient educational programs to train the case workers, community workers and others who will be needed in these new models; the need to resource new programs to effectively work in different environments; and the costs of the new technologies and infrastructure needed to support this work. Identifying and supporting competencies for providers to implement and thrive under value-based models will be critical for the success of payment reform, and is a topic of a companion discussion paper in the Vital Directions series, “Competencies and Tools to Shift Payments from Volume to Value” by Governor Mike Leavitt and colleagues.

Inadequate Performance Measures and the Burden of Excessive Measurement

New payment systems require robust measures of performance to better ensure that providers are delivering high-value, quality care to their patients, in addition to reducing the cost of care. While measures are important sources of accountability, measures themselves will not improve care quality (Dunlap et al., 2009; Pronovost et al., 2016). Unless carefully developed and applied, performance and quality measures can function as little more than a burden for providers, particularly when they target aspects of care they cannot easily, if at all, control. In such cases, measures can deter providers from participating in alternative payment models (Miller, 2014). For example, when the regulations for the Medicare Shared Savings Program were first proposed, they included 65 different quality measures, yet made no changes to the existing fee-for-service framework in place. Unsurprisingly, the regulations received a great deal of scrutiny, leading CMS to bring down the number of measures to 33 in the final regulations.

Further, even in the presence and use of large numbers of performance measures, there may be aspects of care quality and/or performance that are not being measured, such as those related to specialty care, where cost containment and reduction efforts are anticipated to focus (Miller, 2014). Related, there are many dimensions of “value” to patients that are difficult to measure and are not measured at all. Equally concerning, many of the measures used by payers are further processes of marginal relevance to outcomes, and sometimes with even perverse implications for value and costs.

Nonetheless, reliable and valid measurement is fundamental to the implementation of value-based payment models, and CMS has been working to shift its quality measurement from mostly process measures to mostly outcome measures, while reducing the total number of measures in its programs and models. Looking ahead, building more meaningful outcomes measures will require access to more robust and comparable patient-reported data and information. Building this capability will require a significant investment, but the anticipated return that would result from better outcome measures producing better, more efficient care would seemingly justify the initial investment (Miller, 2014). Further work must be done to ensure that collection and reporting of these measures can be integrated seamlessly into provider workflow, and not pose an excessive burden.

Regulatory and Legal Hurdles

Additional barriers to payment reform are imposed by certain existing regulations designed for a fee-for-service system (AHA, 2016), e.g., regulations offering cash incentives under fee-for-service models. Further, a number of laws and regulations impair efforts to create the care coordination and collaboration that is being encouraged through federal payment reforms, including:

- The Patient Referral Law, more often called the Stark Law, which has grown beyond its original intent to prevent physicians from referring their patients to a medical facility in which they have an ownership interest, to limit practically any financial relationship between hospitals and physicians. The law’s strict requirements mandate that compensation be set in advance and paid on the basis of hours worked. Consequently, health care providers are concerned that payments tied to quality and care improvement could violate this law.

- The Civil Monetary Penalty Law (CMP) is a vestige of concerns raised in the 1980s that Medicare patients might not receive the same level of services as other patients after the inpatient hospital prospective payment system bundled multiple services under a single Diagnosis Related Group (DRG). While health reform is about encouraging the use of best practices and clinical protocols, using incentives to reward physicians for following best practices and protocols can be penalized under the CMP law.

- Anti-kickback laws, which originally sought to protect patients and federal health programs from fraud and abuse by making it a felony to knowingly and willfully pay anything of value to influence the referral of federal health program business. Today’s expanded interpretation includes any financial relationship between hospitals and doctors, which has the potential to discourage clinical integration.

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Rules prevent a tax-exempt institution’s assets from being used to benefit any private individual, including physicians. This complicates clinical coordination arrangements between not-for-profit hospitals and private clinicians.

Certain Medicare regulations also may impose limitations on what provider organizations can do to streamline, integrate, and reform care delivery. For example:

- A small system consisting of three or four hospitals in reasonable proximity to each other is not allowed to centralize the oversight of the nursing staff, which would promote use of uniform protocols, the sharing of staffing to meet patient surges, or a unified approach to oversight and education of nurses.

- Conditions of Participation—conditions established by CMS that must be met by organizations to participate in Medicare and Medicaid programs—have been interpreted to mean that a hospital serving a rural community cannot rent clinical space to visiting specialists a few days a month so local patients can more conveniently and routinely see the specialist treating their particular condition. As a result, patients may have to travel great

distances for their specialist visits. This restriction on specialty “rental” in hospitals is in part a result of CMS concerns that such rentals will encourage specialists to reclassify themselves as outpatient providers and significantly increase their payment rates. Clarification and resolution of these issues is important. - Medicare payment rules meant to limit patients sent to specific post-acute care settings as a way of controlling Medicare costs under fee-for-service may prevent certain patients from obtaining services in the most appropriate and efficient settings.

CMS has relaxed some of these requirements in more advanced payment reform models, such as its “Next Generation” ACO model and its other programs that enable ACOs to accept “downside” risk. But the right balance is not yet clear between restrictions to limit volume and intensity in payment models that partially shift to value-based payments, but retain a fee-for-service infrastructure.

Finally, some state laws also impose barriers to integrated care arrangements, including laws that: prohibit the employment of physicians (corporate practice of medicine laws); govern the scope of practice of health professionals; govern the use of telemedicine and other distance services; and govern those deemed to be insurers based on the amount of risk they take on for patient services. Requirements for insurers to have adequate capitalization and to comply with insurance regulations while reflecting the need for financial protection for those covered by the entity may not be good fits for provider-based arrangements.

Limited Evidence on Successful Payment Models

Payment reform requires developing better evidence on the payment reforms themselves. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid innovation, and many states, employers, and health plans, are testing a growing number of payment reform models; but, in many cases, evaluations are not performed at all and the evaluations that are performed could be done more effectively. Overall the evidence is accumulating and diffusing slowly, given the volume of payment reform activity underway. In particular, there is still limited evidence on determinants of successes for Medicare ACOs and the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) (McClellan et al., 2015). Overall, the early financial performance of MSSP ACOs has been found to be highly variable (across ACOs and geographically)—with some ACOs generating major shared savings, and others more marginal shared savings. Early findings also indicate that large ACOs do not have an advantage over smaller ACOs in terms of financial performance, and that there appears to be no meaningful association between initial financial performance and overall quality (McClellan et al., 2015). In fact, a relatively small share of ACOs demonstrated both favorable cost and quality trends.

More data about ACO features, activities, and performance need to be developed and shared, so that best practices and determinants of success can be identified and implemented (Bodaken et al., 2016). Linking more detailed CMS data on ACO features and performance would facilitate the process of identifying what organizations can do to improve performance and better ensure success. Ultimately, getting more ACOs to commit to two-sided risk models and undertake more extensive payment reforms will require the identification of evidence-based determinants of success, as well as clear demonstrations and pathways to succeed under these models.

Safeguarding Against Unintended Consequences

Consolidation and Market Power

As payment reform and the adoption of value-based models of care delivery has proceeded, so has a trend toward provider integration and consolidation. Under emerging models, providers are more accountable for the cost and quality of care provided to pre-defined patient populations. This, combined with additional quality reporting requirements and penalties for hospital readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions, has contributed to provider integration, as they try to better manage care and mitigate costs across the continuum (AHA, 2014).

Provider integration can be clinical or financial, horizontal or vertical, and can exist at the level of non-binding agreements on through to the level of complete mergers (AHA, 2014; Vaida and Wess, 2015). On the whole, integration aims to benefit and improve care quality, cost, and access. Integration can improve efficiency and quality through greater care coordination and increased communication and information-sharing among providers. In this way, integration can reduce unnecessary or duplicative tests and procedures, and other forms of wasteful spending, while ensuring patients receive the right treatment at the right time. To the same effect, integration can reduce the burden of administrative costs, make greater use of resources, such as specialists, and improve the breadth of care available. It can also improve the patient experience by providing more comprehensive care and streamlined access.

Alongside the benefits, there is some concern that provider consolidation can, in some circumstances, lead to higher prices and spending, since larger, consolidated organizations have greater market power, and thus more negotiating power, over prices with private insurance companies (McClellan et al., 2016). In addition to higher prices and outpatient spending, some studies indicate that increasing rates of hospital provider integration have not always resulted in more efficient, quality care or better outcomes for patients (Gaynor and Town, 2012; Neprash et al., 2015).

With the recent Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), it is possible that providers may be more apt to integrate. Originally passed in April 2016, MACRA replaces the old sustainable growth-rate formula for physician payment with a new model to move providers away from fee-for-service towards value-based payment. MACRA presents two payment pathways for providers (collectively called “the Quality Payment Program”): the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), which adjusts fee-for-service payments according to a composite measure of quality and value, and advanced APMs, which transition from fee-for-service payment. MIPS is a consolidation of Medicare’s existing quality reporting programs intended to reduce possible financial penalties incurred by providers and increase the likelihood that providers will attain bonus payments. Components of MIPS include quality activities, clinical improvement activities, advancing care information performance, and cost/ resource use. MIPS has been described as MACRA’s “base program,” which all providers must participate in (or get an exemption from), or face a payment cut (Wynne, 2016). Those providers participating in Advanced APMs (the second pathway) are exempt from MIPS and are eligible for 5% bonus payments beginning in 2019. For APMs to be considered “advanced,” they must bear more than a nominal financial risk for the costs of care provided (McClellan et al., 2016).

Few existing Medicare APMs meet the criteria for “advanced” status. As such, under MACRA as originally proposed, there was the potential that many small and midsize practices would be met with increased administrative burdens resulting from additional reporting requirements, and would be incapable of bearing the financial risk required to qualify for bonus payments. In such cases, smaller practices could be inclined to merge with larger practices or health systems. Acknowledging these concerns, in its final rule, CMS took steps to support smaller practices implementing alternative payment models. Notably, CMS increased the minimum threshold requirements for participation in MIPS ($30,000 in Medicare claims or at least 100 Medicare patients per year), and has allowed for the creation of “virtual groups”, whereby up to ten clinicians can band together to report as one group. CMS also agreed to provide $100 million in technical assistance to smaller practices participating in MIPS over the next five years, and instituted lower reporting thresholds than those originally proposed.

Stifling Valuable Health Care Innovation and Treatment

Some have expressed concern that value-based payment schemes and risk-based reimbursement models might stifle valuable health care innovation and treatment by putting increasing pressure on manufacturers to provide unrealistic evidentiary support demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of their products within constrained time-frames. As bundled payment approaches evolve, it will be important to ensure the payment environment does not discourage investments in new devices or medications that potentially have enormous benefit to patients and potentially reduce lifetime care costs. Innovative drugs and devices, and new potentially curative treatments like regenerative medicine and gene therapies, may avert downstream costs of medical complications. But those downstream cost savings may not be realized until years later. They may not fit into the usual proximal timeframe for payment models.

In the case of pharmaceuticals, discussions of value may take place at the time of the launch but typically do not account for the benefit of the drug over its lifecycle. For example, HIV drugs are estimated to have generated a societal benefit exceeding $750 billion (NBER, 2015). Similarly from 1987-2008, consumers are estimated to have captured $947.4 billion (76 percent) of the total societal value of the survival gains from statins (Grabowski et al., 2015).

Biomedical innovations often represent valuable breakthroughs for patients in terms of longer and better lives. Their development often involves significant time, cost, and uncertainty. Estimates of the average present-value cost of bringing a new drug to market have increased from $1 billion in 2000 to, by some estimates, as much as $2.6 billion in 2015 (DiMasi et al., 2016). If there is no clear path for per-capita or per episode payments to reflect the value of breakthrough technologies, then pharmaceutical companies and device manufacturers will be reluctant to make the necessary investments.

These issues are especially notable for the emerging “curative,” one-time treatments. Despite recent progress in payment reforms for health care providers, current payment models for most drugs are based on payment for units (e.g. pills and vials) and do not consider that a patient could be cured after a single treatment. Payers are coming to recognize that the binary concept of experimental vs. medically necessary is based on a simplified view of evidence and uncertainty, and that more nuanced policy mechanisms are necessary to align with the continuous health technology assessment and reimbursement as a one-off snapshot, to seeing them as ongoing processes aiming at providing greater certainty about value for money as evidence accumulates (Henshall and Schuller, 2013).

The prospects for prevention-oriented, long-term interventions such as gene therapies underscore the fact that biomedical science appears to be advancing more rapidly than the payment and regulatory infrastructure required to deliver it. While some promising payment reforms are being piloted and implemented, the U.S. health care system remains centered on the delivery of traditional chronic treatments whose payments are focused on units and whose value is realized in the near-term. Current coverage policies and payment mechanisms are not well designed to support early interventions that can blunt the onset of a chronic disease, and do not capture the potential benefits over an extended period of time. New analytic tools are needed to assess the benefits of potential one-time curative therapies whose value proposition, delivery, and payment do not align well with conventional payment models. The emerging possibility of gene therapy could serve as a valuable pilot project to aid in the design and implementation of new managed product innovation and use agreements that seek to align the interests of payers, providers, policymakers, and biopharmaceutical companies with those of patients who need access to transformative therapies. This is consistent with the coverage-with-evidence development concept proposed a decade ago, but not yet widely implemented.

In addition, there is a need for the patient voice to be a larger part of the conversation on medical innovation and access to new therapies. While there are efforts to better involve patients in the regulatory process, more can and should be done to ensure patient input is utilized. For example, the FDA’s recent guidance document (FDA, 2015) and work through the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC, 2015), which seeks to create a framework and catalog of patient preference measurement tools, ought to help regulators and medical terminology sponsors better incorporate patients’ perspectives into the approval process.

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

To enable payment reform to fulfill its promise of promoting high-value, patient-centric care, four vital directions are identified for policy makers’ consideration.

- Align the implementation of payment reform to encourage provider efforts to improve quality and value. The federal government should increase support for existing collaborations, such as the Health Care Payment Learning Action Network and the Core Quality Measures Consortium, which are helping to reduce burden on providers, who are trying to navigate many different benchmarks, measures, risk adjustment methods, reporting requirements, and even payment models. Assistance is also needed with identifying and implementing patient-reported measures, particularly for those patients with serious or complex illnesses. To improve performance, providers need timely access to claims data from payers, as well as key clinical information from other institutions—preferably in standard ways that facilitate action. More robust data should be matched by more tools and resources to help clinicians share best practices and learn from successes and failures; care transformation will necessitate ongoing investment in analytics, new skill sets, personnel, and new models of care. Further, laws and regulations originally designed for a fee-for-service system (e.g. the Patient Referral (Stark) Law, Civil Monetary Penalty Laws, anti-kickback laws) need to be reformed. These regulations pose barriers to the advancement of payment reform approaches, patient engagement, as well as many care coordination and transformation efforts.

- Address and incorporate costly but potentially lifesaving technologies. Neither traditional fee-for-service payments for costly technologies, nor alternative payment models that do not account for high-cost but high-value innovation, provide a clear path for high-value biomedical innovation. However, some payment models both within and outside the US have begun to align drug and device payments directly with accountability for improved outcomes or reduced spending for a population of patients. Rather than viewing payment reforms for biomedical technologies and for health care providers as distinct, CMS and private payers could encourage developers of alternative payment models to engage on ways to maximize the value brought by new technologies. For example, this could include model frameworks and regulatory clarifications for sharing data related to the benefits and risks of new technologies for particular patients, or for incorporating drug and device shared accountability in ACOs and bundled payments.

- Ensure that payment reform does not exacerbate adverse consolidation and market power. While some large organizations have achieved better outcomes and lower costs through integrated care, many organizations including small primary-care practices and specialty groups have improved care without consolidation (McWilliams et al., 2016). Reflecting the risks of market power, larger organizations that have consolidated with the stated goal of improving outcomes and lowering costs should report on whether they are achieving these results. Better and more comparable quality and cost measures are needed to help payers, purchasers, and patients recognize and support better care – measures that use not only claims data but also clinical and patient data to better reflect the results that matter for patients, particularly those with serious illnesses. Larger organizations, in particular, have the capacity to produce such measures. Advanced payment models with proportionally smaller financial risks should be developed for smaller provider organizations – like ACOs led by primary care physicians and specialty providers who focus on specialized types of episodes of care.

- Conduct more timely and efficient evaluations of what is working. CMS evaluates Medicare payment reform pilots, and other evaluations have been reported (Mechanic, 2016). But those evaluations often occur on a costly one-off basis, using data that have to be generated outside of care delivery, and hundreds of payment reforms are being implemented in public and private health care programs across the country without substantial evaluation. Common data models and research networks now develop data and use validated methods to evaluate medical technologies and medical practices more quickly. These approaches could provide models for lower-cost, faster learning about the right directions and steps in payment reform.

The era of payment reform has introduced transformative models of health care delivery focused on producing better outcomes, lower costs, and greater investment in new and innovative treatments that are truly valuable. Despite the challenges that remain, by shifting payments to reward the value rather than the volume of health care services, the U.S. health care system is making important strides toward making care more affordable, efficient, and person-centric. Of course, successful execution of payment reform will require related, complementary reforms including: redesigning medical education to include a greater focus on value and patient-focused team care; training more health workers to support value-based, person-centric care; as well as changes in benefit design for patients and consumers. Combined with these advances, through payment reform and high-value innovation, the nation can achieve better care, smarter spending, and healthier people.

References

- Abrams, M, R. Nuzum, M. Zezza, J. Ryan, J. Kiszla, and S. Guterman. 2015. The Affordable Care Act’s Payment and Delivery System Reforms: A Progress Report at Five Years. Commonwealth Fund. 1816, Vol. 12. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_issue_brief_2015_may_1816_abrams_aca_reforms_delivery_payment_rb.pdf (accessed August 14, 2020).

- AcademyHealth and Bailit Health Purchasing, LLC. Facilitators and Barriers to Payment Reform. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, September 2013. Available at: http://www.bailit-health.com/articles/092713_bhp_rwjf_facilitators.pdf (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). 2016. Defining the PMCH. Available at: https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Aligning Forces for Quality (AF4Q). 2011. Talking about Health Care Payment Reform with U.S. Consumers: Key Communications Findings from Focus Groups. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/04/talkingabout-health-care-payment-reform-with-u-s–consumers.html (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Aligning Forces for Quality (AF4Q). 2014. Engaging Consumers in Payment Reform Efforts That Impact Care Delivery Practices. Available at: http://forces4quality.org/af4q/download-document/7282/Resource-rwjf411721.pdf (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Alliance of Community Health Plans (ACHP). 2016. Rewarding High Quality: Practical Models for Value-Based Physician Payment. Available at: http://www.achp.org/wp-content/uploads/ACHP-Report_Rewarding-High-Quality_4.20.16.pdf (accessed November 2, 2016).

- American Hospital Association (AHA). 2005. Strategies for Leadership: Advancing the Practice of Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/2005/pdf/resourceguide.pdf (accessed January 3, 2017).

- American Hospital Association (AHA). 2014. The Value of Provider Integration. Available at: http://www.aha.org/content/14/14mar-provintegration.pdf (accessed November 15, 2016).

- American Hospital Association (AHA). 2016. Legal (Fraud and Abuse) Barriers to Care Transformation and How to Address Them. Available at: http:// www.aha.org/content/16/barrierstocare-full.pdf (accessed November 15, 2016).

- Aon Hewitt. 2014. Aon Hewitt 2014 Health Care Survey. Available at: http://www.aon.com/attachments/human-capitalconsulting/2014-Aon-Health-Care-Survey.pdf (accessed November 2, 2014).

- Berenson, R. and N. Cafarella. 2012. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation: Activity on Many Fronts. Urban Institute. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/25076/412499-The-Center-for-Medicare-and-Medicaid-Innovation-Activity-on-Many-Fronts.PDF (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Bodaken, B., R. Bankowitz, T. Ferris, J. Hansen, J. Hirshleifer, S. Kronlund, D. Labby, R. MacCornack, M. McClellan, and L. Sandy. 2016. Sustainable Success in Accountable Care. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org10.31478/201604d

- Boeing. 2016. Preferred Partnership: An innovative approach to health care. Available at: http://www.healthpartnershipoptions.com/SiteAssets/pub/index.html (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 2015. Better Care. Smarter Spending. Healthier People: Paying Providers for Value, Not Volume. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Factsheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-01-26-3.html (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 2016a. National Health Expenditure Data – Historical. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-andsystems/statistics-trends-and- reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nationalhealthaccountshistorical.html (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 2016b. Innovation Models. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/index.html#views=models (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Davis, K., S. Guterman, S. Collins, K. Stremikis, S. Rustgi, and R. Nuzum. 2010. Starting on the path to a high performance health system: analysis of the payment and system reform provisions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. Commonwealth Fund. 1442. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2010/sep/starting-path-high-performance-health-system-analysis-payment (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Delbanco, S. 2015. The Payment Reform Landscape: Impact on Consumers. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/04/15/the-payment-reform-landscapeimpact-on-consumers/ (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 2015. Better, Smarter, Healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/01/26/better-smarter-healthier-in-historic-announcementhhs-sets-clear-goals-and-timeline-for-shifting-medicare-reimbursements-from-volume-to-value.html (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Devore, B.L. and L. Cates. Disruptive Innovation for Healthcare Delivery. Presbyterian Healthcare Services and Intel. Available at: http://www.intel.com/content/dam/www/public/us/en/documents/white-papers/disruptiveinnovation-healthcare-delivery-paper.pdf (accessed November 2, 2016).

- DiMasi, J.A., H.G. Grabowski, and R.W. Hansen. 2016. Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: New Estimates of R&D Costs. Journal of Health Economics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.01.012

- Dunlap, M.E., P.J. Greco, B.L. Halliday, and D. Einstadter. 2009. Lack of correlation between HF performance measures and 30-day rehospitalization rates. Journal of Cardiac Failure 15:283.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2015. Patient Preference Information-Submission, Review in PMAs, HDE Applications, and De Novo Requests, and Inclusion in Device Labeling; Draft Guidance for Industry, Food

and Drug Administration Staff, and Other Stakeholders. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm446680.pdf (accessed November 2, 2016). - Gaynor, M., and R. Town. 2012. The Impact of Hospital Consolidation – Update. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Synthesis Report. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2012/06/the-impact-of-hospitalconsolidation.html (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Grabowski, D.C., D.N. Lakdawalla, D.P. Goldman, et al. 2012. The large social value resulting from use of Statins warrants steps to improve adherence and broaden treatment. Health Affairs 31(10):2276–2285. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1120

- Guterman S, K. Davis, K. Stremikis, and H. Drake. 2010. Innovation in Medicare and Medicaid will be central to health reform’s success. Health Affairs 29(6):1188–1193. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0442

- Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network. 2016. Alternative Payment Model (APM) Framework Final White Paper.

- Health Care Transformation Task Force (HCTTF). 2016. About Health Care Transformation Task Force. Available at: http:// hcttf.org/aboutus/ (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Henshall, C. and T. Schuller. 2013. Health Technology Assessment, Value-Based Decision Making, and Innovation. International Journal of Technological Assessment in Health Care 29:353-359. https://doi.org/10.1017/S02666462313000378

- Hoo, E. and D. Lansky. 2016. Medical Network and Payment Reform Strategies to Increase Health Care Value. American Health Policy Institute and Pacific Business Group on Health. Available at: http://www.americanhealthpolicy.org/Content/documents/resources/Medical_Networks_AHPI_2016.pdf (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10027.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). 2010. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12750.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). 2013. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2013. https://doi.org/10.17226/13444.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council (NRC). 2013. U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13497.

- Institute for Patient-And Family-Centered Care (IPFCC).2002. Creating patient and family advisory councils. Available at: http://www.ipfcc.org/advance/Advisory_Councils. pdf (accessed November 2, 2016).

- McClellan, M., S.L. Kocot, and R. White. 2015. Early evidence on Medicare ACOs and next steps for the Medicare ACO program. Health Affairs Blog. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/01/22/early-evidenceon-medicare-acos-and-next-steps-for-the-medicareaco-program/ (accessed November 2, 2016).

- McClellan, M., F. McStay, and R. Saunders. 2016. The Roadmap To Physician Payment Reform: What It Will Take for All Clinicians to Succeed under MACRA. Health Affairs Blog. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/ blog/2016/08/30/the-roadmap-to-physician-payment-reform-what-it-will-take-for-all-clinicians-tosucceed-under-macra/ (accessed November 2, 2016).

- McGinnis, T. and J. Newman. 2014. Advances in MultiPayer Alignment: State Approaches to Aligning Performance Metrics across Public and Private Payers. Available at: http://www.milbank.org/wp-content/files/documents/

MultiPayerHealthCare_WhitePaper_071014.pdf (accessed November 2, 2016). - McKesson. 2016. Consider the Alternative. Available at: http://www. mckesson.com/blog/consider-the-alternative/ (accessed November 2, 2016).

- McWilliams, J.M., L.A. Hatfield, M.E. Chernew, B.E. Landon, and A.L. Schwartz. 2016. Early performance of accountable care organizations in Medicare. New England Journal of Medicine https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1600142.

- Mechanic, R.E. 2016. When new medicare payment systems Collide. New England Journal of Medicine. 374(18):1706–1709. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1601464.

- Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC). 2015. Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC) Patient-Centered Benefit-Risk Project Report: A Framework for Incorporating Information on Patient Preferences Regarding Benefit and Risk into Regulatory Assessments of New Medical Technology. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/95591/download (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Miller, J. 2014. ACA Medicare Reforms Improve Patient Experiences. Available at: https://hms.harvard.edu/news/acamedicare-reforms-improve-patient-experiences (accessed November 2, 2016).

- National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). 2005. The National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 11810. Who Benefits from New Medical Technologies? Estimates of Consumer and Producer Surpluses for HIV/AIDS Drugs. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w11810 (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Neprash, H.T., M.E. Chernew, A.L. Hicks, T. Gibson, J.M. McWilliams. 2015. Association of Financial Integration Between Physicians and Hospitals With Commercial Health Care Prices. JAMA Internal Medicine 175(12):1932-1939. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4610.

- Pronovost, P. J., J. M. Austin, C. K. Cassel, S. F. Delbanco, A. K. Jha, B. Kocher, E. A. McGlynn, L. G. Sandy, and J. Santa. 2016. Fostering Transparency in Outcomes, Quality, Safety, and Costs: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201609i

- Rajkumar, R, P. H. Conway, and M. Tavenner . 2014. CMS—Engaging Multiple Payers in Payment Reform. JAMA 311(19):1967-1968. https://doi.org/10.1001/ jama.2014.3703

- Schilling, B. 2011. Advancing Quality Through Employer-Led Initiatives, The Commonwealth Fund. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/advancing-quality-through-employer-led-initiatives (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Seidman, J., C. Kelly, N. Ganesan, and A. Gray. 2015. Payment Reform on the Ground: Lessons from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Alternative Quality Contract. Avalere Health LLC. Available at: http://www.bluecrossma.com/visitor/pdf/avalere-lessons-from-aqc.pdf (accessed November 2, 2016).

- The Henry J. Kaiser Foundation (KFF). 2016. Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population, Timeframe: 2015. Available at: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/ (accessed November 2, 2016).

- Vaida, B. and A. Wess. 2015. Health Care Consolidation – An Alliance for Health Reform Toolkit. Available at: http://www.allhealth.org/publications/Consolidation-Toolkit_169.pdf health care consolidation alliance (accessed November 15, 2016).

- Wynne, B. 2016. MACRA Final Rule: CMS Strikes A Balance; Will Docs Hang On? Health Affairs Blog. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/10/17/macra-final-rulecms-strikes-a-balance-will-docs-hang-on/(accessed November 2, 2016).