Nurse Suicide: Breaking the Silence

TW: suicide

If you are suicidal and need emergency help, call 911 immediately or 1-800-273-8255 if in the United States. If you are in another country, find a 24/7 hotline at www.iasp.info/resources/Crises_Centres.

ABSTRACT | The purpose of this paper is to raise awareness of and begin to build an open dialogue regarding nurse suicide. Recent exposure to nurse suicide raised our awareness and concern, but it was disarming to find no organization-specific, local, state, or national mechanisms in place to track and report the number or context of nurse suicides in the United States. This paper describes our initial exploration as we attempted to uncover what is known about the prevalence of nurse suicide in the United States. Our goal is to break through the culture of silence regarding suicide among nurses so that realistic and accurate appraisals of risk can be established and preventive measures can be developed.

Introduction

“Change only happens when ordinary people get involved, and they get engaged, and they come together to demand it.”

— Pres. Barack Obama [1]

The available US data on nurse suicide are outdated [2-8] yet provide clues that suicide may be a risk of the nursing profession. The purpose of this paper is to begin breaking through the silence surrounding nurse suicide by commenting on the authors’ collective experiences following exposure to nurse suicide. We describe our quest to understand the frequency and underlying causes of nurse suicide and suggest strategies on how to move forward. While nurses face a number of mental health and psychological challenges—including anxiety, compassion fatigue, depression, ethical issues, and second-victim syndrome—the focus of this paper is on the most silent, irreversible, and devastating mental health scourge: suicide. Three examples from nurses regarding actual experiences with nurse suicide and suicidal ideation are explored. Cases are blinded for privacy and occurred at more than one organization.

Absence of Procedures

The loss of a nurse colleague to suicide is more common than generally acknowledged [9-11] and is often shrouded in silence, at least in part due to stigma related to mental health and its treatment [12,13]. After a suicide, nurses grieve in different ways as they continue to deliver patient care. A standard operating procedure for how to handle the suicide of a nurse colleague does not exist, compared with what is available for physicians [14,15]. Without a predefined process, each unit manager is left to independently develop a grief recovery plan to support the staff in processing resultant emotions. In our collective experience, no one, at any level, was comfortable talking about suicide when it occurred. One nurse leader speaks of her experience following a suicide.

“I found out through a whisper in the wind. Not a memo. Not an announcement. Just chatter. Then later, another whisper; another event. Again, there was no formal announcement. I thought more about the memos we received about key events with the physicians and how that seemed to be handled so differently. Each of their losses is sent out as a mass email so that anyone touched by that person could know, reach out to the family or friends, and grieve together. In this situation, each manager prepared their own action plan to process their staff through the grief, fielding the event independently. I was not a member of those departments, yet the news moved me in a profound way. I wanted to process it. I didn’t even know the nurses personally, yet I wanted to know more. I felt unsettled and needed closure. Maybe it was because I am a scientist and saw the pattern emerge. I was fixated on determining one of two things: Was there anything we could do to prevent this in the future, or on the contrary, should I resolve myself to the fact that suicide happens? I knew that everyone was doing the best they could do to deal with the situation, but also questioned whether there were best practices somewhere else to learn from. I wondered about whether or not having more than one event in an organization was unusual. I attempted to seek out best practices, went to the internet and then to the literature. The results were sobering.”

Searching for Answers

Networking with Colleagues

After direct experience with nurse suicide, the authors networked with local and national professional colleagues, collecting anecdotes confirming that others had experienced nurse suicides, either personally or through work responsibilities. We even found one case example while conducting research on the impact of blame in the workplace [16]. From this, we learned that the incidents were not isolated to our organizations. Others had experienced similarly tragic losses of colleagues, but no one offered suggestions of best practices in suicide prevention or nurse suicide grief recovery. We attempted to find information about the incidence of nurse suicide through inquiries to human resources and risk management departments, boards of registered nursing, the American Nurses Association, and the California Board of Registered Nursing. Surprisingly, none of these organizations collected or reported information about nurse suicide. Other than the testimonies of single events recalled from memory and the one published case study, we found no examples of processes to prevent, cope with, or deal with nurse suicide. Therefore, despite knowledge that nurse suicide exists, we came to the conclusion, as others had before us, that the occurrence of nurse suicide was shrouded in silence, avoidance, and denial [13].

A General Internet Search

A general internet search produced no public data identifying a national nurse suicide rate, yet data on suicide rates were readily available for physicians, teachers, police officers, firefighters, and military personnel (Table 1).

Source: Davidson et al., “Nurse suicide: Breaking the silence,” National Academy of Medicine | Notes: [a] American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 2013, Physician and medical student depression and suicide prevention, https://afsp.org/our-work/education/physician-medical-student-depression-suicide-prevention (accessed June 3, 2017); [b] Teacher Mental Health, 2011, Teacher suicide rates, http://www.teachermentalhealth.org.uk/teachersuicide.html (accessed May 20, 2017); [c] The Badge of Life, 2016, A study of police suicide 2008-2016, http://www.policesuicidestudy.com (accessed May 1, 2017); [d] Fire Companies, 2017, Firefighter close calls 2017, http://www.firefighterclosecalls.com/?s=suicide (accessed April 15, 2017); [e] Kessler, R., M. Stein, P. Bliese, E. Bromet, W. Chiu, K. Cox, L. J. Colpe, C. S. Fullerton, S. E. Gilman, M. J. Gruber, S. G. Heeringa, L. Lewandowski-Romps, A. Millikan-Bell, J. A. Naifeh, M. K. Nock, M. V. Petukhova, A. J. Rosellini, N. A. Sampson, M. Schoenbaum, A. M. Zaslavsky, and R. J. Ursano, 2015, Occupational differences in US Army suicide rates, Psychological Medicine 45(15):3293-3304.

This rudimentary review further confirmed that nurse suicide in the US appeared, indeed, invisible. There was no dialogue about incidence of nurse suicide, not even on the expansive reach of the internet.

From discussion with the San Diego County medical examiner [17], we found that transparency in this area is complicated by a lack of standardized reporting of death by suicide. The reporting characteristics vary from county to county; some do not include occupation. Further, in states that do report occupation, the occupation code is usually entered in free text, resulting in difficulty constructing a methodology for accurate data analysis. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintains a restricted National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), which is the most comprehensive death registry by suicide coded by occupation. It has been growing yearly, and at the time of this writing, data are available for 40 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico [18]. The NVDRS dataset is available only by application. We confirmed that no one has queried this dataset to search for nurse suicide statistics. Despite the challenge of occupation coding in CDC mortality data and restricted access to the incomplete NVDRS dataset, it is curious that the incidence rates for other professions were reported on the internet, yet nurses have not addressed this issue to date.

US Nurse Suicide Literature Review

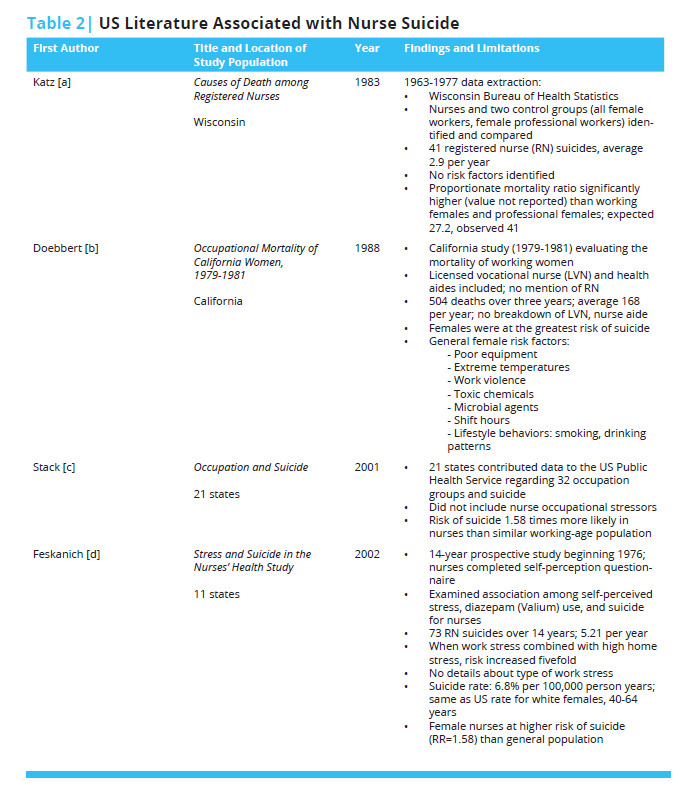

From the global review of lay postings on the internet, we moved to a search of the professional literature. With the support of a medical librarian, a search strategy was developed and executed in PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO for English-language papers, with no limitations on time period or publication type. A National Center for Biotechnology Information alert using this search strategy ((suicide) AND nurs*) NOT “assisted suicide”) NOT euthanasia)) was then created to generate weekly updates. Many anecdotal reflections were located. These were published by nurses whose colleagues had completed suicide [19-26]. The literature search yielded only five dated descriptive studies regarding incidence of nurse suicide in the US. Two additional studies were obtained by tracing older references from review papers. All references from relevant papers were combed in an attempt to identify additional studies. Studies reporting data regarding nurse suicide in the US are summarized in Table 2. Because of the dearth of current literature on this subject, older references are included, further highlighting the need for current attention to the topic of US nurse suicide.

A 1999 review [11] of nurse suicide data—including Doebbert [5], Katz [3], Milhelm [4], and Powell [2]—from the US concluded, “there is a remarkable paucity of empirically based information from which to identify clear causal factors and, equally importantly, preventive factors.” Nearly 20 years later, that statement holds true.

Source: Davidson et al., “Nurse suicide: Breaking the silence,” National Academy of Medicine | Notes: [a] Katz, R. M., 1983, Causes of death among registered nurses, Journal of Occupational Medicine 25(10):760-762; [b] Doebbert, G., K. R. Riedmiller, and K. W. Kizer, 1988, Occupational mortality of California women, 1979-1981, Western Journal of Medicine 149(6):734; [c] Stack, S., 2001, Occupation and suicide, Social Science Quarterly 82(2):384-396; [d] Feskanich, D., J. L. Hastrup, J. R. Marshall, G. A. Colditz, M. J. Stampfer, W. C. Willett, and I. Kawachi, Stress and suicide in the Nurses’ Health Study, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 56(2):95-98.

Occupational Risks

Safety Measures

In the US, there are 3.4 million practicing nurses representing the largest group of health care professionals [27]. Workers’ compensation data are universally reported, including injuries by type, days of work lost to injury, and cost. Organizations may also track leave of absence due to stress. We have found no evidence that hospitals measure employee loss due to suicide. Further, more than one of the nurse suicides in the anecdotes we uncovered occurred shortly following separation from the job. If a suicide metric existed, these cases would have likely been lost to capture because the nurses were no longer employees.

Occupational Pressures

Internationally, outdated studies point to factors that appear relevant today to nursing in the US: ethical conflicts, organizational deficits, role ambiguity, shift work, social disruption of families due to work hours, team conflict, and workload [28,29]. In two US studies performed using a secondary analysis of the longitudinal Nurses’ Health Study data, a combination of work and home stress, smoking, stress, and Valium use were identified as suicide risk factors [7,8]. A critical review [30] on risk factors of nurse suicide identified nine studies published globally since the previous review [11], of which there were two US papers [6,7]. This review found that collective risks factors leading to nurse suicide included access to means, depression, knowledge of how to use lethal doses of medications and toxic substances, personal and work-related stress, smoking, substance abuse, and undertreatment of depression [30].

The high-pressure nursing environment and its associated demands have been clearly addressed within the literature [31-34]. Burnout among nurses is common [35-38]. Caring and compassion come at a price [39,40]. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, American Nurses Association, and Association of Nurse Executives all recognize the stress in the profession and have called for action to optimize a healthy work environment [41-45]. The profession of nursing entails demanding and stressful work, with frequent exposure to human suffering and death. Many nurses point to daily ethical issues and ethics-related stress, perceive limited respect in their work, and are increasingly dissatisfied with their work situations [46].

Cumulative stress may be related to administration of potentially inappropriate treatment, blame, inadequate equipment, insufficient labor resources, lateral violence, medication or medical errors, and moral distress (the result of being prevented from doing what you feel is right) [47-51]. Review of medical errors, near misses, and omissions of care traditionally focus on the clinical situation. The key question in a case review is, “What can we do to prevent this from happening again?” However, the emotional toll of being involved in a case with adverse outcomes is often neglected. The question “How did being involved in this make you feel?” is rarely addressed.

In today’s complex health care environment, nurses have more responsibility and accountability. The care nurses deliver is highly regulated. Nurses are under constant pressure to perform the required care within strict time limits. Spending less time with patients is linked to patient readmissions due to complications [52]. Thus, while burnout is common and painful in its own right, it also leads to suboptimal performance and patient safety issues, and is intimately associated with depression [38,53], a known precursor to suicide [54,55].

It is not known why some people experience despair and hopelessness as a result of negative workplace situations and others can use those environments for stress-induced growth [56]. Depression is a common mental disorder, with a prevalence of 14.6 percent among adults in high-income countries and 11.1 percent in developing countries [57,58]. While there are no reliable published data on the true prevalence of major depressive disorder among nurses, in the United States, one study showed that the prevalence of depressive symptoms among nurses was 41 percent, while another reported it to be 18 percent [59,60].

Nurses as Whole People

It has been suggested that, although work stressors alone are important, when they are combined with stress from home, suicide risk may increase in nurses [7]. The balance of personal and professional values often is neglected in clinical practice. Nurses may “wall off” personal issues to remain in a professional mode with their patients. In a study on workplace wellness, it was reported that nurses feel cared for when leaders recognize them as whole people, acknowledging the troubles they might be having at home as well as at work [61]. A small 1996 study of 30 nurses and 60 nursing students documented that nurses who had less emotional expression were at an increased risk of depression, which may lead to suicidal ideation [62]. Nurses are also a community within their particular units and, perhaps, need to begin to speak more directly to one another on issues that matter personally as well as professionally. Nurses need to take time to ask themselves and their colleagues, “Are you okay today?” The nursing profession also needs to move beyond the stigma of mental illness and psychological concerns. Nurses may too often hold themselves to a higher standard, and they might feel shameful or disinclined to confront their own issues with mental health because they are trained to help others, not themselves. In the following quote, we hear a hint that nursing culture might further drive suicide risk by discouraging nurses from seeking help.

“I remember when I was hired in the intensive care unit [ICU] on the night shift after having moved to a new town where my husband had taken a new job. I had about 7 years of ICU experience by that time and chose to work nights to maximize family time and reduce day-care for my toddlers.

“The culture was quite different from my previous hospital. The night nurses were noticeably less collaborative, with more of a ‘get your own work done so you can sit and read’ attitude. I was much more used to a culture of ‘no one sits down until everyone can sit down.’ The day shift culture and nurses seemed different, but maybe that was because of the day-shift supervisor Penny [not her real name] was a bright ray of light. I remember Penny very well. She looked like a perfect West Coast girl, tan, beautiful white teeth sparkling in her warm smile; energetic and always warm and friendly with a hint of mischievousness. A consummate professional, Penny was a fierce patient advocate and was loved by the staff, physicians and families. I really looked up to her and knew as I matured as a nurse, I wanted to be like Penny. Her leadership on the dayshift was reflected in the culture I observed at change of shift and missed in my night shift colleagues.

“I’d been at my new job for about 6 months when I received a call from a day shift nurse in the late afternoon asking if I could come in early to start my night shift. There had been a tragedy amongst the staff and there were day shift nurses who were unable emotionally to finish their shifts. When I asked, what had happened, the day charge nurse told me Penny had died. They were looking for relief to allow the grieving nurses to go home. Without a second thought, I said I’d be there as soon as I could. When I arrived, it was clear something terrible had happened. Everyone in the ICU was red-eyed from crying and looking shell-shocked. When I asked, what happened to Penny, I was told she was found dead at her home by her husband, whom she had recently separated from. I was shocked and saddened as well by the news but since I only knew Penny from our brief encounters at staff meetings and change of shift, I was able to contain my own emotions enough to relieve one of her closest colleagues of her assignment so she could go home.

“Many weeks later, after the funeral and many sad and mournful days in our unit, we were told Penny’s death was due to an intentional injection of a neuromuscular blocking agent. She had removed the drugs from the unit’s secured drug storage locker the day before, at the end of her shift just before leaving. Only those very close to her knew of her marital problems. No one at work would ever suspect Penny was suffering so much in her personal life. She never let her pain show. Interactions with Penny were always upbeat and positive. She really did find time to laugh and have fun while expertly running a busy unit.

“We all missed Penny terribly in those months after her suicide. We all asked ourselves how we could have missed or misjudged her degree of despair over her failing marriage. We all hugged our families a little longer and treated each other more gently after we lost Penny. Unfortunately, the culture on nights in ICU did not improve and I requested a transfer to the surgical trauma unit on the opposite side of the hospital. The ICU just wasn’t the same without Penny and the staff was still struggling with emotions. I’ll never forget Penny, her wonderful personality and gift as a nurse and leader. I still struggle with how someone with so many caring colleagues, access to support and help could have seen no hope in her situation. I can’t even begin to imagine how her family must have felt (and still feel). I’ve since learned that suicide is a complex and dynamic emotional condition. There are stigmas that need to be overcome so nurses (and all people) suffering from depression, hopelessness and despair know they can seek help and will not be judged. Maybe Penny thought because she was a nurse, she should be able to handle her life situation and depression on her own.”

Prevention Strategies

Although minimal attention has been paid to preventing suicide among nurses compared with what has been done regarding physicians [15,63], it is clear that there are similar considerations with burnout, depression, and suicide risk [36,38,64-68]. Suicide prevention is a complex undertaking that involves both institutional and individual efforts. In this section, we highlight one institutional and one individual approach.

Institutional Strategies

As health care professional burnout and suicide risk become more recognized and discussed, institutions and hospitals are beginning to respond and provide programs aimed at enhancing physician and nurse wellness [41,43,69,70]. One academic center, University of California San Diego, School of Medicine, developed a mental health program, the Healer Education Assessment and Referral (HEAR) Program, initially for physicians, residents, and medical students [15,71,72]. Following a physician suicide in 2009, a committee led by two psychiatry faculty working in collaboration with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) developed a two-pronged program for the prevention of depression and suicide. One element of the program provides a voluntary, anonymous, web-based screening and referral program using a validated assessment tool developed by the AFSP. The second element includes systemwide grand rounds education, including topics such as physician burnout, depression, and suicide [15]. During the initial year of the program, 27 percent (101) of the individuals screened met criteria for significant risk for depression or suicide, and nearly half of those identified (48) accepted referrals for mental health evaluation and treatment. From the beginning, the program was supported by senior leadership from the medical school, who stated that no stigma should be attached to mental illness and encouraged everyone to participate in the program because physician well-being was and is a high priority [15]. The following year, the University of California, Skagg’s School of Pharmacy was added to the program’s agenda. Since its inception, this program for physicians has been adopted by over 60 medical campuses. Finally, in its seventh year, after experiencing nurse suicides, the HEAR Program was extended to the nursing community.

The HEAR Program is now being piloted as a quality improvement project at the University of California, San Diego Health, to test whether the program will identify high-risk nurses and successfully move them into treatment. In the first 10 months since the expansion of the program to nurses, HEAR has assessed 184 nurses, of which 16 (9 percent) dialogued with the counselor online through the encrypted website, 15 (8 percent) engaged with counseling in person or by phone, and 20 (11 percent) received and accepted personalized referrals to psychologists and psychiatrists. Per the results of the AFSP Interactive Screening Program [73]—which includes the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 depression screening tool [74,75] and validated questions on suicide risk—an astounding 97 percent of the 184 nurses who answered the survey were found to be at moderate or high risk. The results demonstrate an obviously biased sample of at-risk nurses. However, more importantly, the bias demonstrates that proactive anonymous screening will identify nurses who are at risk. As was found previously with physicians [15], nurses commented that without this proactive screening, they would not otherwise have initiated mental health care. The HEAR Program, including this proactive depression- and suicide-risk screening for physicians, has been endorsed by the American Medical Association as a best practice in suicide prevention [76].

As a society, we need to better understand the factors that influence depression. Through analysis of the data received through the HEAR interactive screening, we can begin to understand the specifics behind risk factors of stress. In the HEAR program extension pilot [77], we found the following workplace stressors in nurses at high risk for suicide: feelings of inadequacy, lack of preparation for the role, lateral violence, and transferring to a new work environment.

Individual Strategies

It is not enough for institutions to take on the burden of reducing nurse suicide. There is much individuals can do for themselves to develop healthy coping and resilience, modify self-perpetuated stigma, and provide better self-care, including mental health care [13]. For our last personal account with suicide, we present this vignette written by a nurse who was experiencing depression and thought about taking her life. Her experience with depression was shared to encourage an open dialogue among nurses and to encourage nurses to take action and seek professional help when depressed.

“I am a creature of habit; and so I begin each day in the same manner as I have done for the past 21 years: I stumble out to the kitchen in my pajamas to turn on the coffee maker; empty the dishwasher while I wait for the coffee to brew, then proceed to the master bath—coffee in hand, to take my antidepressants. As my sister, brother, mother, aunts, uncles, great aunts, and grandmother before me, I have been diagnosed with major depression. Too many of these tortured souls lost their battles with depression; forever traumatizing the loved ones who found them.

“Besides being a creature of habit, I am a wife, a mother, a grandmother, and a registered nurse with a long and successful career. In my 30’s, my genetic disposition to depression began to creep into my life. Once delighted by my children’s antics, I now simply observed. I smiled and clapped at their words and accomplishments because I knew that was what a loving mother should do, yet inside, I felt nothing. After putting each child to bed at night with a kiss on their foreheads, I could immerse myself in self-loathing: How could anyone stand to be around me? I was fat, I was ugly, I was empty, and I was ignorant. But mostly, I was fearful that someone would someday see me for the fraud that I was. I tossed and turned—so tired, yet unable to sleep. The next day I would get up and resume the act; and the same the next day and the next.

“At work, I was the person in charge, the person to go to with questions, the person who could turn chaos into order, and the person who could make even the most complex physiology make sense. Leaving the unit at the end of the shift, I often stood on the top deck of the parking garage staring at the road below thinking ‘It wouldn’t be so bad. Just one quick painful thud and then peace. If I jumped right, I’d hit head first, and wouldn’t feel anything at all. No one I loved would have to be traumatized by the blood and the displaced bones and organs.’ And then I’d realize that I couldn’t leave that legacy to my children, couldn’t abandon them, couldn’t leave them without a mother; couldn’t teach them that suicide was the way to take care of pain, and I’d turn and go home. After nearly a year, I finally realized that I was no longer who I once was. I was not the mother that I wanted to be, and was not feeling all the complex emotions of life. I called my doctor, asked for help, and started on the road back to myself. A few months after beginning medication, I heard an unfamiliar sound—laughter. It took me a minute to realize—it was coming from me! I was experiencing joy!

“Although I still need the occasional medication adjustment, I am so very grateful that science has created effective antidepressants. If the treatments that are available today were available in past decades, I am certain that my family’s history would have been very different. I feel lucky that I and my children are genetically predisposed to a condition that is easily treatable. I have not dwelt on it, but have been open with them about depression, so that they may recognize the signs of depression if those signs ever emerge in themselves or others, and will know how to get help. I’ve also been open in the workplace about being treated for depression. A co-worker once pulled me aside and thanked me for my openness. She told me that she had come to work on a particular evening intent upon taking an overdose of sleeping pills and narcotics upon her return home. While at work, however, she heard me tell the story of my decision to ask for help for my depression. ‘So I went home,’ she said, ‘threw away the meds, and called my doctor.’

“I’ve been told that the piano and I each have 88 keys. It takes both the low and the high notes and chords to compose a concerto; so I experience the lows, but I know that the highs are waiting for me in the next line. It’s wonderful to hear and live it all.”

Conclusion

Nurse suicide has been a hidden phenomenon in the profession and has not been adequately measured or studied within the United States. The time for a culture change is now. Research is needed to assess the magnitude of nurse suicide and associated work stressors. We have applied for, and received the NVDRS dataset and have begun an investigation to define the incidence of nurse suicide. The study will include psychological autopsies, including circumstances leading to suicide, the emotional state of the nurse prior to the event, pre-existing psychiatric conditions and treatment, trauma, violence, and home and work stressors. Open, transparent communication is needed to address pertinent issues related to nurse suicide. Strategies to identify, prevent, and mitigate nurse burnout and depression and prevent suicide need to be tested. Once available, research results, coupled with institutional and individual grit, can help transform the culture of the nursing profession from silence and isolation to one of shared dedication to nurse health and wellness, ultimately contributing to optimal patient care. Until such data are available, silence and the preventable loss of life will prevail.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! Real-life experiences presented in a new @theNAMedicine discussion paper aim to shed light on an often under-recognized threat to our health care system: nurse suicide http://ow.ly/jO9J30hBmqf

Tweet this! Real-life experiences presented in a new @theNAMedicine discussion paper aim to shed light on an often under-recognized threat to our health care system: nurse suicide http://ow.ly/jO9J30hBmqf

![]() Tweet this! “I found out through a whisper in the wind. Not a memo. Not an announcement. Just chatter.” New @theNAMedicine discussion paper examines why nurse suicide is rarely discussed: http://ow.ly/jO9J30hBmqf

Tweet this! “I found out through a whisper in the wind. Not a memo. Not an announcement. Just chatter.” New @theNAMedicine discussion paper examines why nurse suicide is rarely discussed: http://ow.ly/jO9J30hBmqf

![]() Tweet this! Despite established suicide prevention programs for physicians, the same support networks don’t always exist for nurses. Find out more about the silent issue of nurse suicide: http://ow.ly/jO9J30hBmqf

Tweet this! Despite established suicide prevention programs for physicians, the same support networks don’t always exist for nurses. Find out more about the silent issue of nurse suicide: http://ow.ly/jO9J30hBmqf

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- Obama, B. 2017. President Obama’s farewell address. The New York Times, January 10. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/10/us/politics/obama-farewell-address-speech.html?_r=0 (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Powell, E. H. 1958. Occupation, status, and suicide: Toward a redefinition of anomie. American Sociological Review 23(2):131-139. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2088996 (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Katz, R. M. 1983. Causes of death among registered nurses. Journal of Occupational Medicine 25(10):760-762. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-198310000-00017

- Milham, S. 1983. Occupational mortality in Washington state. Publication number 83-116. Washington, DC: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/83-116/pdf/83-116.pdf?id=10.26616/NIOSHPUB83116 (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Doebbert, G., K. R. Riedmiller, and K. W. Kizer. 1988. Occupational mortality of California women: 1979-1981. Western Journal of Medicine 149(6):734. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1026629/ (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Stack, S. 2001. Occupation and suicide. Social Science Quarterly 82(2):384-396. https://doi.org/10.1111/0038-4941.00030

- Feskanich, D., J. L. Hastrup, J. R. Marshall, G. A. Colditz, M. J. Stampfer, W. C. Willett, and I. Kawachi. 2002. Stress and suicide in the Nurses’ Health Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 56(2):95-98. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.56.2.95

- Hemenway, D., S. J. Solnick, and G. A. Colditz. 1993. Smoking and suicide among nurses. American Journal of Public Health 83(2):249-251. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.83.2.249

- Milner, A., M. J. Spittal, J. Pirkis, and A. D. LaMontagne. 2013. Suicide by occupation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry 203(6):409-416. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128405

- Kolves, K., and D. De Leo. 2013. Suicide in medical doctors and nurses: An analysis of the Queensland Suicide Register. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 201(11):987-990. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000047

- Hawton, K., and L. Vislisel. 1999. Suicide in nurses. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 29(1):86-95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.1999.tb00765.x

- Smith, G. B., and E. Hukill. 1996. Nurses impaired by emotional and psychological dysfunction. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association 2(6):192-200. https://doi.org/10.1177/107839039600200603

- Ross, C. A., and E. M. Goldner. 2009. Stigma, negative attitudes and discrimination towards mental illness within the nursing profession: A review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 16(6):558-567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01399.x

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). 2013. Physician and medical student depression and suicide prevention. Available at: https://afsp.org/our-work/education/physician-medical-student-depression-suicide-prevention (accessed March 20, 2017).

- Moutier, C., W. Norcross, P. Jong, M. Norman, B. Kirby, T. McGuire, and S. Zisook. 2012. The suicide prevention and depression awareness program at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine. Academic Medicine. 87(3):320-326. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824451ad

- Davidson, J. E., D. L. Agan, S. Chakedis, and Y. Skrobik. 2015. Workplace blame and related concepts: An analysis of three case studies. Chest 148(2):543-549. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.15-0332

- Personal communication, J. Lucas, San Diego County, Anatomic Pathology and Clinical Pathology, San Diego County Medical Examiners, March 2016.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. National Violent Death Reporting System. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/nvdrs/index.html (accessed January 3, 2018).

- Wilkins, M. 1977. Suicide: A suicidal R.N.’s crisis, part 1. Registered Nurses 40(9):54-57.

- Reguero, C. 1979. Suicide: The ultimate cry for help: How nurses can answer, part 2. Journal of Practical Nursing 29(1):21-22.

- Mericle, B. P. 1993. When a colleague commits suicide. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 31(9):11-45. Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/med/8229909 (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Belanger, D. 2000. Occupational hazards: Nurses and suicide: The risk is real. Registered Nurses 63(10):61-64. Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/med/11062669 (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Lynn, C. W. 2008. When a coworker completes suicide. American Association of Occupational Health Nurses Journal 56(11):459-469. https://doi.org/10.1177/216507990805601104

- Cooke, L., J. Gotto, L. Mayorga, M. Grant, and R. Lynn. 2013. What do I say? Suicide assessment and management. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 17(1):E1-E7. https://doi.org/10.1188/13.CJON.E1-E7

- Farthing, S. 2015. Another one of our own is gone too soon. Florida Nurses 63(2):19. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26259381/ (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Tramutola, K. 2015. Suicide among nurses. New Jersey Nurse 45(4):1. Available at: https://d3ms3kxrsap50t.cloudfront.net/uploads/publication/pdf/1240/NJ10_15.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

- The American Nurse. 2016. ANA calls for a culture of safety in all health care settings. Available at: http://www.theamericannurse.org/index.php/2016/07/1Nurses2/ana-calls-for-a-culture-of-safety-in-all-health-care-settings (accessed April 15, 2017).

- Heim, E. 1991. Job stressors and coping in health professions. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 55(2-4):90-99. https://doi.org/10.1159/000288414

- Tan, C. C. 1991. Occupational health problems among nurses. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 17(4):221-230. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1709

- Alderson, M., X. Parent-Rocheleau, and B. Mishara. 2015. Critical review on suicide among nurses: What about work-related factors? Crisis 36(2):91-101. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000305

- Sherman, D. W. 2004. Nurses’ stress and burnout: How to care for yourself when caring for patients and their families experiencing life-threatening illness. The American Journal of Nursing 104(5):48-56, quiz 7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000446-200405000-00020

- Institute of Medicine. 2004. Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10851

- Vollers, D., E. Hill, C. Roberts, L. Dambaugh, and Z. R. Brenner. 2009. AACN’s healthy work environment standards and an empowering nurse advancement system. Critical Care Nurse 29(6):20-27. https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn200263

- Kramer, M., and C. Schmalenberg. 2008. Confirmation of a healthy work environment. Critical Care Nurse. 28(2):56-63. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18378728/ (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A., C. Vargas, C. San Luis, I. García, G. R. Cañadas, and I. Emilia. 2015. Risk factors and prevalence of burnout syndrome in the nursing profession. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 52(1):240-249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.07.001

- Epp, K. 2012. Burnout in critical care nurses: A literature review. Dynamics 23(4):25-31. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23342935/ (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Hooper, C., J. Craig, D. R. Janvrin, M. A. Wetsel, and E. Reimels. 2010. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and compassion fatigue among emergency nurses compared with nurses in other selected inpatient specialties. Journal of Emergency Nursing 36(5):420-427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2009.11.027

- Johnson, J., G. Louch, A. Dunning, O. Johnson, A. Grange, C. Reynolds, L. Hall, and J. O’Hara. 2017. Burnout mediates the association between depression and patient safety perceptions: A cross‐sectional study in hospital nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 73(7):1667-1680. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13251

- Maslach, C., and M. P. Leiter. 2016. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 15(2):103-111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

- Maslach, C. 2003. Burnout: The cost of caring. Cambridge, MA: Malor Books.

- American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. 2015. Is your work environment healthy? Available at: http://www.aacn.org/wd/hwe/content/hwehome.pcms?menu=hwe (accessed April 15, 2017).

- American Nurses Association. 2015. Nursing: scope and standards of practice. Silver Spring, MD.

- American Nurses Association. 2017. 2017 year of the healthy nurse. Available at: http://nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ThePracticeofProfessionalNursing/2017-Year-of-Healthy-Nurse (accessed April 15, 2017).

- American Nurses Association. 2015. Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. Silver Spring, MD.

- American Organization of Nurse Executives. 2005. AONE nurse executive competencies. Nurse Leader 3(1):15-21. Available at: https://www.aonl.org/sites/default/files/aone/nec.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Ulrich, C., P. O’Donnell, C. Taylor, A. Farrar, M. Danis, and C. Grady. 2007. Ethical climate, ethics stress, and the job satisfaction of nurses and social workers in the United States. Social Science and Medicine 65(8):1708-1719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.050

- Davidson, J. E., S. Chakedis, and D. Agan. In progress. Developing and testing of the blame-related distress survey.

- Davidson, J. E., D. L. Agan, and S. Chakedis. 2015. Exploring distress caused by blame for a negative patient outcome. Journal of Nursing Administration 46(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000288

- Epstein, E. G., and A. B. Hamric. 2009. Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. The Journal of Clinical Ethics 20(4):330. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20120853/ (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Hamric, A., E. Epstein, and K. White. 2013. Moral distress and the hospital. In Healthcare ethics for healthcare organizations: A moral imperative, edited by S. Mills, G. Filerman, and P. Wehane. Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press.

- Jameton, A. 1993. Dilemmas of moral distress: Moral responsibility and nursing practice. AWHONN’s Clinical Issues in Perinatal and Women’s Health Nursing 4(4):542-551. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8220368/ (accessed September 1, 2020).

- The Joint Commission. 2011. Health care worker fatigue and patient safety. Sentinel Event Alert (48). Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_48.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Bianchi, R., I. S. Schonfeld, and E. Laurent. 2015. Burnout-depression overlap: A review. Clinical Psychology Review 36:28-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.004

- Isometsä, E. 2014. Suicidal behaviour in mood disorders—who, when, and why? The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 59(3):120-130. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405900303

- Nock, M. K., I. Hwang, N. A. Sampson, and R. C. Kessler. 2010. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry 15(8):868-876. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2009.29

- Rushton, C. H. 2016. Moral resilience: A capacity for navigating moral distress in critical care. AACN Advanced Critical Care 27(1):111-119. https://doi.org/10.4037/aacnacc2016275

- Bromet, E., L. H. Andrade, I. Hwang, N. A. Sampson, J. Alonso, G. de Girolamo, R. de Graaf, K. Demyttenaere, C. Hu, N. Iwata, A. N. Karam, J. Kaur, S. Kostyuchenko, J. Lepine, D. Levinson, H. Matschinger, M. E. Medina Mora, M. O. Browne, J. Posada-Villa, M. C. Viana, D. R. Wiliams, and R. C. Kessler. 2011. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Medicine 9:90. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-90

- World Health Organization. 2001. The world health report 2001: Mental health: New understanding, new hope. Geneva, Switzerland. Available at: http://www.who.int/whr/2001/en (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Letvak, S., C. J. Ruhm, and T. McCoy. 2012. Depression in hospital-employed nurses. Clinical Nurse Specialist 26(3):177-182. https://doi.org/10.1097/NUR.0b013e3182503ef0

- Ruggiero, J. S. 2005. Health, work variables, and job satisfaction among nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration 35(5):254-263. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200505000-00009

- Baggett, M., L. Giambattista, L. Lobbestael, J. Pfeiffer, C. Madani, R. Modir, M. M. Zamora-Flyr, and J. E. Davidson. 2016. Exploring the human emotion of feeling cared for in the workplace. Journal of Nursing Management 24(6):816-824. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12388

- Diggs, K. A., and D. Lester. 1996. Emotional control, depression and suicidality. Psychological Reports. 79(3, Pt 1):774.

- Center, C., M. Davis, T. Detre, D. E. Ford, W. Hansbrough, H. Hendin, J. Laszlo, D. A. Litts, J. Mann, P. A. Mansky, R. Michels, S. H. Miles, R. Proujanksy, C. F. Reynolds III, and M. M. Silverman. 2003. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: A consensus statement. JAMA 289(23):3161-3166. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.23.3161

- Dyrbye, L. N., F. S. Massie Jr., A. Eacker, W. Harper, D. Power, S. J. Durning, M. R. Thomas, C. Moutier, D. Satele, J. Sloan, and T. D. Shanafelt. 2010. Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA 304(11):1173-1180. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1318

- Dyrbye, L. N., M. R. Thomas, F. S. Massie, D. V. Power, A. Eacker, W. Harper, S. Durning, C. Moutier, D. W. Szydlo, P. J. Novotny, J. A. Sloan, T. D. Shanafelt. 2008. Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Annals of Internal Medicine 149(5):334-341. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008

- Embriaco, N., E. Azoulay, K. Barrau, N. Kentish, F. Pochard, A. Loundou, and L. Papazian. 2007. High level of burnout in intensivists: Prevalence and associated factors. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 175(7):686-692. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200608-1184OC

- Epperson, W. J., S. F. Childs, and G. Wilhoit. 2016. Provider burnout and patient engagement: The quadruple and quintuple aims. Journal of Medical Practice Management 31(6):359-363. Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/med/27443059 (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Pompili, M., G. Rinaldi, D. Lester, P. Girardi, A. Ruberto, and R. Tatarelli. 2006. Hopelessness and suicide risk emerge in psychiatric nurses suffering from burnout and using specific defense mechanisms. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 20(3):135-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2005.12.002

- Shapiro, J., and P. Galowitz. 2016. Peer support for clinicians: A programmatic approach. Academic Medicine 91(9):1200-1204. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001297

- Post, S. G., and M. Roess. 2017. Expanding the Rubric of “Patient-Centered Care” (PCC) to “Patient and Professional Centered Care” (PPCC) to Enhance Provider Well-Being. HEC Forum 29(4):293-302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-017-9322-7

- Downs, N., W. Feng, B. Kirby, T. McGuire, C. Moutier, W. Norcross, M. Norman, I. Young, and S. Zisook. 2014. Listening to depression and suicide risk in medical students: The Healer Education Assessment and Referral (HEAR) Program. Academic Psychiatry 38(5):547-553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0115-x

- Zisook, S., I. Young, N. Doran, N. Downs, A. Hadley, B. Kirby, T. McGuire, C. Moutier, W. Norcross, and M. Tiamson-Kassab. 2015. Suicidal ideation among students and physicians at a US medical school: A Healer Education Assessment and Referral (HEAR) Program report. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying 74(1):35-61. https://doi.org/0030222815598045

- AFSP. 2017. Interactive Screening Program. Available at: https://afsp.org/our-work/interactive-screening-program (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Kroenke, K., R. L. Spitzer, and J. B. W. Williams. 2001. The PHQ‐9. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16(9):606-613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Kroenke, K., and R. L. Spitzer. The PHQ-9: A new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiatric Annals 32:509-521. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06

- Brooks, E. 2017. Preventing physician distress and suicide. Available at: https://www.stepsforward.org/modules/preventing-physician-suicide#section-steps (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Davidson, J. E., S. Z Sizook, B. Kirby, G. DeMichelle, and B. Norcross. 2018. Suicide prevention: A Healer Education and Referral (HEAR) Program for nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration 41(2). https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000582

Clinician Well-Being, Mental Health and Substance Use, Nursing, Quality and Safety, Workforce