Investing in Children to Promote America’s Prosperity

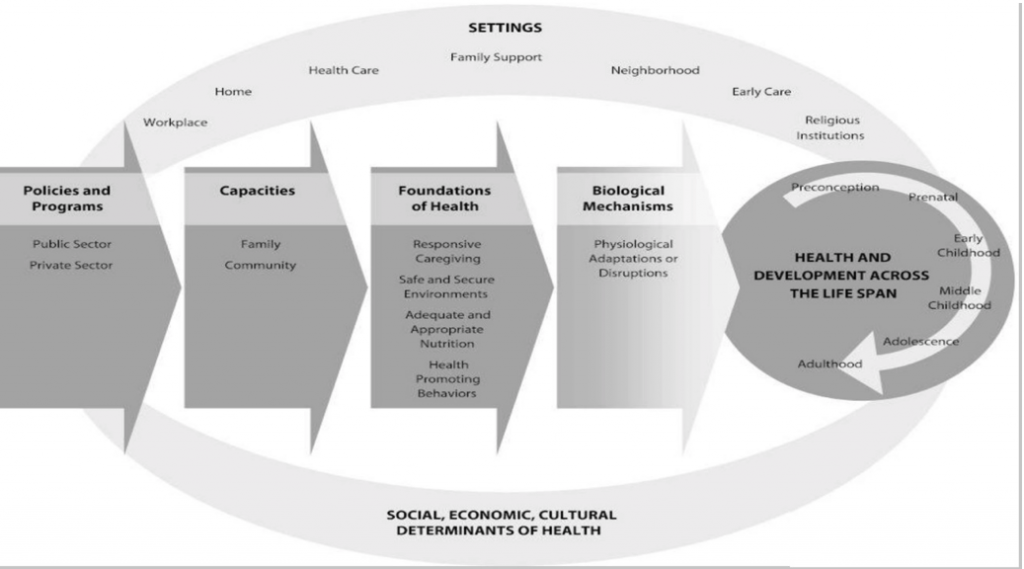

“America, the land of opportunity” has been the historical rallying cry inspiring individuals to work their hardest to succeed. Although today’s children will determine our nation’s future prosperity, scientists have repeatedly demonstrated that individuals are rarely able to fully determine their own destiny—especially in matters of health and well-being. Decades of research have shown that children’s physical health, mental health, and well-being are significantly influenced by the states, communities, neighborhoods, and families in which they live (see Figure 1) [1], and that reducing investments to these infrastructures may be done at the expense of children’s health. Our nation’s increased investments in health over the last 10 years have resulted in improvements in health and reductions in the prevalence of chronic diseases, obesity, and asthma [2]. These investments have also resulted in positive community-wide shifts in health, resources, opportunities, and norms. Yet there is a call for investments in other domains. Sustained and expanded investments in the contexts that surround and nurture children are needed to promote the health and well-being of children across the United States. Thereby, these investments ensure our nation’s long-term prosperity.

Quite simply, environmental contexts either foster healthy behaviors and relationships or, conversely, increase children’s risk for poor outcomes. For the last 40 years, scientists have repeatedly and rigorously experimented to identify efficacious and cost-effective intervention approaches. Investments in these evidence-based programs and policies support families and communities so that children’s development and lifelong productivity increase. Likewise, policies and programs that directly reduce adverse social risks, such as community violence, improve the health and well-being of children and parents [3].

Figure 1 | A New Framework for Childhood Health Promotion: The Role of Policies and Programs in Building Capacity and Foundations of Early Childhood Health

SOURCE: Mistry, K. American Journal of Public Health, September 2012; 102(9): 1688-1696. Reprinted with permission from The Sheridan Press on behalf of the American Public Health Association.

At this time, policy makers are challenged to choose how, and in what, to invest for America’s future. With investments that provide access to basic resources, supportive environments, and nurturing interpersonal relationships, children will thrive, and their capacities increase developmentally with age—ultimately leading to healthy families, a vital workforce, and strong communities. However, research has shown that even short-term reductions in foundational investments in children, families, and communities can have broad, sustained, and negative consequences for children’s health and their parents’ productivity and employment [4]. The country has already seen examples of the consequences of such shortsightedness: the children and families of Flint, MI, will spend their lives trying to undo the poisoning conferred from one year of cost-saving on water.

While the benefits of investments in health clearly result in better health, investments in community infrastructure also yield better health outcomes. Epidemiological researchers have demonstrated that when basic structures are missing in a community—for example, affordable housing—there is a significant increase in a community’s homelessness and mental health burden, as well as children’s problematic school behaviors [5]. If housing and case management are provided to homeless families, as was demonstrated in New York City several years ago, these challenges disappear [6]. Investments in affordable housing and supports for homeless families should be considered as we face the fact that 2.5 million families are expected to be homeless this year [7]. Also, factors such as parental unemployment and job instability affect health outcomes for children. Thus, providing employment supports improves children’s outcomes and reduces maternal depression [8]. Even when states merely enact minimum wage laws and provide tax credits for the poor, population health is better than in states without such laws [9]. Therefore, limiting investments in community infrastructure is one example of toxic community stress that sets children on a trajectory of poor health into adulthood, threatening national prosperity.

Similarly, investments in the education system contribute to improved lifelong health and long-term workforce productivity [10]. Toxic stress experienced by children and families—from the daily challenges of poverty, institutional racism, trauma, and community violence—is linked to mental health disorders and poor health outcomes. Investments made in education—including professional learning opportunities for educators, early care and education programs, school mental health clinics and support services, and school/classroom environment—can buffer the stress that many families experience. These investments also help to engage children who are frequently absent from school, thus, increasing graduation rates. An educated workforce leads to stronger workforce engagement and improved health over the life course. Likewise, investments in mental health systems may provide quality care and access to the 55 percent of American communities that lack mental health providers [11]. If there are cuts to education or mental health care, the most affected will be children who face daily stresses—and these are the children for whom we should instead be making the greatest investments.

Thus, current investments in community infrastructure, as well as in health and education systems, forecast a future in which our nation’s prosperity can soar, particularly if we expand these investments in communities that serve low-income families and children. Failing to sustain these investments will result in an unprepared and unhealthy workforce and citizenry, and will lead to unintended consequences for our national prosperity. Now is the time for scientists to inform legislators and policy makers about evidence-based interventions, strategies, and tools that can be integrated in communities and implemented with fidelity to improve children’s physical and mental health outcomes. In addition, policy makers must consider the significant, long-term consequences of community cost-cutting initiatives that may strip away key community infrastructure for children and families, crippling the nation.

Regarding the health and well-being of children and families, the evidence is clear: when basic family supports and community infrastructures are damaged or weakened, the next generation suffers from broad, lifelong, negative consequences. It is critical that policy makers, scientists, and program administrators recognize the lessons of the last 40 years: thoughtful national, statewide, and community-level investments in prevention, health care, housing, education, employment, and anti-poverty programs have paid off for America. The country need to continue and expand scientifically supported investments to ensure future prosperity.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! Investing in the health of our children means not only providing for their medical needs, but their mental health, housing stability, access to food, and feeling of overall safety: http://ow.ly/8cRy30j9E7S #investinkids #childrenshealthforum #childrensforum

Tweet this! Investing in the health of our children means not only providing for their medical needs, but their mental health, housing stability, access to food, and feeling of overall safety: http://ow.ly/8cRy30j9E7S #investinkids #childrenshealthforum #childrensforum

![]() Tweet this! “If there are cuts to education or mental health care, the most affected will be children who face daily stresses – and those are the children for whom we should instead be making the greatest investments”: http://ow.ly/8cRy30j9E7S #investinkids #childrenshealthforum

Tweet this! “If there are cuts to education or mental health care, the most affected will be children who face daily stresses – and those are the children for whom we should instead be making the greatest investments”: http://ow.ly/8cRy30j9E7S #investinkids #childrenshealthforum

![]() Tweet this! Investments in education, including early and after-care programs and mental health support systems, can counteract long-term and toxic stress that children in unstable communities may face: http://ow.ly/8cRy30j9E7S #investinkids #childrenshealthforum #childrensforum

Tweet this! Investments in education, including early and after-care programs and mental health support systems, can counteract long-term and toxic stress that children in unstable communities may face: http://ow.ly/8cRy30j9E7S #investinkids #childrenshealthforum #childrensforum

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- Mistry, K. B., C. S. Minkovitz, A. W. Riley, S. B. Johnson, H. A. Grason, L. C. Dubay, and B. Guyer. 2012. A new framework for childhood health promotion: The role of policies and programs in building capacity and foundations of early childhood health. American Journal of Public Health102(9):1688-1696. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300687

- Ford, E. 2005. The epidemiology of obesity and asthma. Allergy and Clinical Immunology 115(5): 897-909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.050

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. 2016. Report to Congress: Social risk factors and performance under Medicare’s value-based purchasing programs. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/253971/ASPESESRTCfull.pdf (accessed October 12, 2017).

- Cannon, J., R. Killburn, L. Karoly, T. Mattox, A. Munchow, and M. Bonventura. 2017. Decades of evidence demonstrate that early childhood investments can benefit children and provide economic returns. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation Research Series. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9993.html (accessed October 12, 2017).

- Childhood Rafferty, Y., and M. Shinn. 1991. The impact of homelessness on children. American Psychologist 46(11):1170-1179. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.11.1170

- Shinn, M., J. Samuels, S. N. Fischer, A. Thompkins, and P. J. Fowler. 2015. Longitudinal impact of a family critical time intervention on children in high-risk families experiencing homelessness: A randomized trial. American Journal of Community Psychology 56(3-4):205-216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9742-y

- American Institutes for Research. n.d. National Center on Family Homelessness. Available at: http://www.air.org/center/national-center-family-homelessness (accessed October 12, 2017).

- Alegria, M., R. E. Drake, H. A. Kang, J. Metcalfe, J. Liu, K. DiMarzio, and N. Ali. 2017. Simulations test impact of education, employment, and income improvements on minority patients with mental illness. Health Affairs 36(6):1024-1031. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0044

- Rigby, E., and M. E. Hatch. 2016. Incorporating economic policy into a “Health-in-all-policies” agenda. Health Affairs 35(11):2044-2052. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0710

- Grossman, M. 2015. The relationship between health and schooling: What’s new. Working paper no. 21609. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w21609.pdf (accessed September 1, 2020).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2013. Report to Congress on the nation’s substance abuse and mental health workforce issues. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://purl.fdlp.gov/GPO/gpo36923 (accessed October 12, 2017).