Integrating Clinical Care with Community Health through New Hampshire’s Million Hearts Learning Collaborative: A Population Health Case Report

Background

Similar to the national rates of high blood pressure, data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System indicate that the New Hampshire rate of hypertension is just over 30 percent (CDC, 2013; New Hampshire Institute for Health Policy and Practice, 2011). Heart disease is the second leading cause of death in New Hampshire, and the rate of hypertension has increased significantly, from 23 percent (95 percent confidence interval: 22 percent, 25 percent) in 2001 to 31 percent (95 percent confidence interval: 29 percent, 32 percent) in 2011 (New Hampshire Institute for Health Policy and Practice, 2011). New Hampshire identified cardiovascular disease as a state health priority in its 2011 State Health Profile, specifying modification of risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, and elevated cholesterol levels, as key dimensions to address (New Hampshire Division of Public Health Services, 2011).

In October 2013, the state of New Hampshire, along with nine other states and the District of Columbia, was awarded a Million Hearts grant by the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Million Hearts is a national initiative working to prevent 1,000,000 heart attacks and strokes by 2017 (CDC, 2015). New Hampshire’s Million Hearts partners include the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Public Health Services; the Institute for Health Policy and Practice at the University of New Hampshire; Cheshire Medical Center/Dartmouth Hitchcock-Keene (CMC/DHK); City of Manchester Health Department (CMHD); Manchester Community Health Center (MCHC); Nashua Department of Public Health and Community Services; Lamprey Health Care–Nashua (LHC-N); and Goodwin Community Health (Goodwin).

New Hampshire’s work was modeled after the successful hypertension control strategies developed and implemented by CMC/DHK. CMC/DHK is a regional medical center with a large, multispecialty physician practice and is responsible for treating more than 12,000 patients with hypertension. The CMC/DHK model, utilizing medical care with integration from community partnerships (described in more detail below), resulted in an improvement in hypertension control within the hospital system from 72 percent to 85 percent over the course of an 18-month period. The New Hampshire Million Hearts project sought to replicate this work in three additional communities, including New Hampshire’s two largest cities (Manchester and Nashua).

Description of the Initiative

The approach of CMC/DHK’s hypertension control effort was systematic. To start, the implementers established a provider planning team, which developed a four-question, multiple-choice questionnaire to be administered to primary care providers and nurses who supported the specified patient population. Using the survey data, CMC/DHK implemented new strategies to help identify and more aggressively treat patients with hypertension. Although the approach was multifaceted, success could be most directly tied to four specific interventions:

- Utilization of a uniform data measure;

- Development of a patient registry;

- Creation of patient engagement information cards; and

- Cultivation of community partnerships.

Data and Measurement

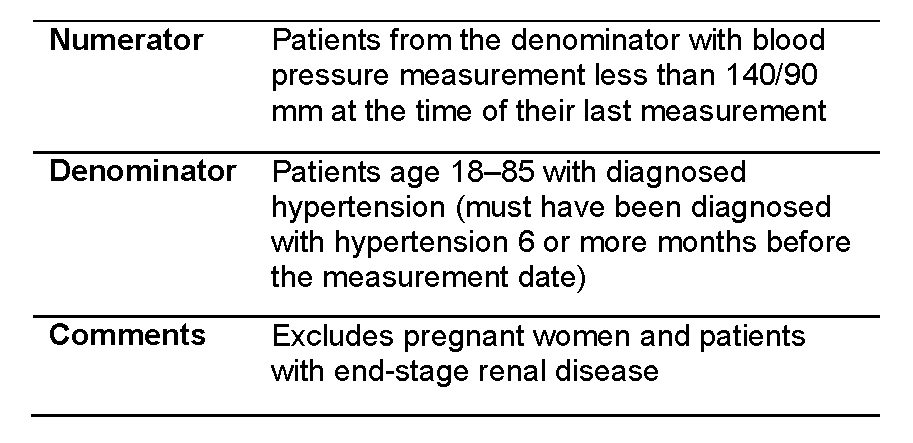

The method of measuring the hypertension control rate was specified for the Million Hearts project using quality measure NQF 0018, which is the hypertension measure supported by the CDC. This measure comes from the National Quality Forum (NQF), a “not-for-profit, nonpartisan, membership-based organization that works to catalyze improvements in healthcare” (National Quality Forum, 2016). NQF 18 is defined as follows:

All reporting related to New Hampshire’s Million Hearts Learning Collaborative was conducted with the NQF 0018 measure, using data extracted by the electronic medical records systems for each site and tied to patient registries (described below). Prior to intervention, all clinical sites provided baseline hypertension control rates. Rates were reported periodically throughout the span of the project to monitor the effect of the selected interventions on overall rates.

Patient Registry

Patient registries provide a system to collect uniform data points about each patient and can be categorized by disease, condition, or other definition to evaluate specific outcomes. The use of a hypertension registry is believed to be one of the most important strategies used by CMC/DHK in effectively managing its patients with hypertension. CMC/DHK recognized that a provider and registry coordinator working together to systematically “manage the registry” could address dozens of patient needs related to poorly controlled hypertension in a very short time (less than 1 hour). Over time, teams learned that additional chronic disease care management and preventive care needs could be added to the registries to provide opportunities to advise about needed immunizations, recommended screenings, and lifestyle modification, such as smoking cessation. Patient registries can also be used to report data on specific outcome measures. For Million Hearts, hypertension control rates were calculated using data points within the patient registries.

Work in Manchester and Nashua followed the model of care developed by CMC/DHK, with each site implementing in its own way, customizing the model based on the specific needs of the clinical site and the community. CMC/DHK provided a template design to MCHC and LHC-N to assist in developing a framework for reporting functionality.

Given the multicultural, multilingual population of patients served by MCHC, with 47 percent of visits requiring translating services, it was important to include nonclinical data to support care decisions. It was also important to consider socioeconomic factors, such as whether patients had access to transportation to and from appointments. Unique indicators captured in this registry included language, insurance status, diabetes diagnosis, transportation needs, and self-management goals. In terms of registry management, MCHC’s work was spearheaded by a registered nurse who coordinates the center’s Patient-Centered Medical Home Project. Support was provided by community health workers, who assisted in managing hypertension for patients who speak Spanish or Arabic.

In addition to an expansive registry, a report with less functionality was created, called Registry-Lite. Indicators captured in this registry include last blood pressure value, date of next appointment, and provider comments. LHC-N chose to implement the hypertension registry using the Registry-Lite version. The site began using this registry with one provider and then expanded use with other providers over time. In terms of registry management, LHC-N also utilized a registered nurse to lead the work. The nurse was supported by a medical assistant, a translator, and a data coordinator.

Goodwin Community Health chose to utilize the full patient registry. For the duration of the funding period, a registered nurse has been given the task of spending one day per week on registry management. Goodwin’s goal moving forward is to transition this work to community health workers.

Patient Engagement

To raise awareness about the importance of hypertension and control within the community, CMC/DHK needed a tool that could be distributed to patients that would educate them about hypertension, provide guidance about making healthy lifestyle choices, and engage them in understanding their biometric numbers. CMC/DHK developed a foldable wallet card to meet this need.

The original wallet card is an eight-panel, foldable white card distributed to patients without hypertension by providers during clinical visits. The goal of this card is to assist patients in preventing hypertension. The wallet card’s messaging was based on existing models considered to be best practices in creating awareness about blood pressure in a community population (Chrostowska and Narkiewicz, 2010; Kaiser Permanente, 2014). The card was successfully piloted in two worksites, with pilot participants reporting identification of newly diagnosed hypertension, lifestyle change, and the sharing of the cards with others. Each time a card is given to a patient by a provider, it is to be used as a tool to begin a brief therapeutic conversation to educate the patient about hypertension as well as the importance of healthy lifestyle choices. Simple scripting was developed to guide conversation, using a traffic light design (green is normal, yellow is prehypertension, and red suggests possible hypertension). Following the success of the pilot, use of the wallet cards expanded across CMC/DHK as well as the Keene community, along with guidance on how to use them most effectively. In November 2012, the cards were featured at the CDC’s Prevention Research Center Summer Seminar Series as a patient engagement tool to be used in clinical and worksite settings.

For New Hampshire’s Million Hearts work, both MCHC and LHC-N incorporated wallet cards into their outreach in both clinical and community settings. In addition to distributing cards in English, they also translated the cards to Spanish and Portuguese (and are working to develop a card in Arabic) to better meet the needs of their diverse patient population. Goodwin Community Health also chose to implement the wallet cards sitewide, including all medical appointments, health education classes, and dental visits.

The wallet cards have been embraced by the New Hampshire Medical Society’s Public Health Task Force and have been co-branded with the logos of the society and Million Hearts. The society has committed to printing wallet cards and distributing them to physician members free of charge for the duration of the Million Hearts initiative.

Community Partnerships

Strong evidence from the Community Preventive Services Task Force indicates that barriers to health improvement are decreased through effective community-clinical collaboration, which increases communication across sectors; improves referrals and tracking; and leads to enhanced coordination of services for individuals (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2014). Recognizing that patient health and the decision-making process are influenced by the environment, CMC/DHK developed partnerships with local community agencies in an effort to support patients more broadly. CMC/DHK and its community partners worked to develop one consistent hypertension education brochure. All community partners agreed to discard previously used brochures and began implementing the new brochure community-wide. Community partners also distributed wallet cards across community settings. Partners included local visiting nurse agencies, the YMCA, and local grocers and restaurants.

In addition, CMC/DHK took the initiative to develop a free nurse clinic. This allowed patients access to regular blood pressure checks without the copay associated with an office visit. Eliminating the cost barrier was a key step in engaging patients to become more involved in controlling their hypertension. With the wallet cards, they were able to document the readings to share with their providers.

In New Hampshire’s Million Hearts project, the communities of Manchester and Nashua identified ways to comprehensively address hypertension within their communities. CMHD partnered with MCHC in the fall of 2013 to develop a sustainable plan for hypertension control within the greater Manchester community. As MCHC took the lead clinically, CMHD tackled the community integration dimensions to bring attention to the need for risk factor reduction in addition to clinical interventions. The first goal for CMHD was to increase access to hypertension screening in the community. CMHD began offering free, walk-in hypertension screening clinics at the health department during regular business hours, Monday through Friday. To improve access throughout the city to those without transportation, CMHD partnered with the Catholic Medical Center’s Parish Nurse Program. Eleven parish nurse clinics, located strategically across the city, participated in the Million Hearts initiative by providing access to blood pressure screening services via free, walk-in clinics. Nurses were equipped with wallet cards available in English, Spanish, and Portuguese.

In addition, CMHD worked with two local organizations, the Granite YMCA–Downtown Manchester Branch and the Organization for Refugee and Immigrant Success, to increase access to affordable places for recreation and healthy food sources. The YMCA provided a reduced-access membership offered to all Million Hearts patients of MCHC and their family members. This membership can be used to access YMCA facilities without any restrictions and costs only $10 per month. The YMCA also provided CMHD and MCHC with five temporary family memberships to distribute as necessary to help build momentum for creating healthier behaviors.

The partnership with the Organization for Refugee and Immigrant Success brings locally grown produce to center-city Manchester. The organization works with immigrant and refugee groups in New Hampshire, helping them to become self-sufficient through farming. Local farmers organize a weekly farm stand on the MCHC campus to provide community members with an opportunity to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables without leaving the city. The farm stand is equipped with Electronic Benefit Transfer/Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program technology to enable customers to utilize their supplemental nutrition (food stamp) benefits. In addition, through a program known as the Double Value Coupon Program, all Electronic Benefit Transfer/Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program transactions are provided a 100 percent match ($1 for $1) to support the purchase of additional fruits and vegetables. The program is supported locally by Wholesome Wave and the New Hampshire Food Bank.

The Nashua Department of Community and Public Health Services partnered with LHCN in the fall of 2013 to develop a sustainable plan for hypertension control within the Nashua community. The partners began their hypertension work by recognizing the need for all individuals to be linked to a permanent medical home. Historically, one of the challenges in providing community-based blood pressure screenings has been the lack of a referral mechanism when a client is identified with hypertension. Clients without primary care providers and/or health insurance have few referral options other than to seek care at local hospital emergency departments or urgent care centers. Through this partnership, a protocol was formalized to streamline the patient referral and enrollment process so that individuals without access to primary care could become permanent patients at LHC-N.

As a next step, the Nashua Department of Community and Public Health Services expanded its offering of hypertension screenings. They began offering free, walk-in blood pressure screenings twice weekly. They also augmented all existing community outreach clinics to include hypertension screenings for all patients, regardless of the type of clinic being offered. Considering the fact that many patients with hypertension are undiagnosed, offering this type of screening to all patients has been very effective. Wallet cards are utilized during all clinic hours.

Goodwin Community Health chose to engage local hospital systems and a community mental health center to build its community relationships. The health center partnered with the emergency departments at two local hospitals to increase the use of wallet cards throughout the community. When patients are seen in these emergency departments and have blood pressure that is above average, members of the medical staff provide them with wallet cards. Patients are then encouraged to follow up with their primary care providers within the next few days. When emergency department patients do not have previously established medical homes, hospital staff work directly with Goodwin Community Health to link these patients with the health center.

Goodwin Community Health also partnered with its local community mental health center, Community Partners. Early review of its patient registry showed the Goodwin quality improvement team that there was a 50 percent comorbidity of hypertension with mental illness. In addition to distributing wallet cards to patients, Community Partners added a hypertension screening component to all patient appointments. Through grant funding, automatic blood pressure monitors were purchased for Community Partners. Staff members were trained by one of Goodwin’s nurses on proper blood pressure technique. Goodwin shares the same electronic health records as Community Partners, and information is easily exchanged between the two sites for shared patients.

The New Hampshire Million Hearts Learning Collaborative led to the development of Ten Steps for Improving Blood Pressure Control in New Hampshire: A Practical Guide for Clinicians and Community Partners, a step-by-step manual to guide practitioners, quality improvement personnel, and practice administrators in improving blood pressure control in clinical practice and through community outreach (Fedrizzi and Persson, 2014). (An electronic version of Ten Steps for Improving Blood Pressure Control in New Hampshire: A Practical Guide for Clinicians and Community Partners (University of New Hampshire, 2015) can be found at http://chhs.unh.edu/ihpp/publications (accessed March 17, 2016). The manual distills the approach developed by CMC/DHK and shares the lessons learned from the New Hampshire Million Hearts Learning Collaborative. When combined, these ten steps provide a comprehensive approach to improving hypertension control rates within communities.

Results

Cheshire Medical Center/Dartmouth Hitchcock-Keene was able to improve its hypertension control rate from 73 percent (8,868 of 12,215 patients) in January 2012 to 85 percent (10,383 of 12,215) in July 2013. This model of care helped 1,515 patients with uncontrolled hypertension move to a safer, more controlled hypertension range in a period of just 18 months.

Replication of this model in the more diverse urban communities of Manchester and Nashua also resulted in improvement. MCHC improved its hypertension control rate from 70 percent (941 of 1,351 patients) in January 2014 to 75 percent (1,040 of 1,391 of patients) by August 2014. LHC-N approached their patients with hypertension in two ways: a single-provider pilot and then a center-wide implementation. In the single-provider pilot, LHC-N reported a baseline control rate of 58 percent (153 of 262 patients) in January 2014. In August 2014, the control rate had increased to 70 percent (169 out of 241 patients). Centerwide, LHC-N reported a baseline control rate of 69 percent (603 of 868 patients). In August 2014, this rate had improved to 72 percent (692 out of 961 patients).

Finally, Goodwin Community Health, the most recent clinical partner, measured improvement as well. In November 2014, the site reported a baseline control rate of 70 percent (599 out of 852 patients with hypertension). At the project end in June 2015, the control rate had increased to 76 percent (707 out of 934 patients with hypertension).

Discussion

The partnerships developed through the New Hampshire Million Hearts Learning Collaborative are prime examples of how the integration of public health and primary care can lead to sustainable models of care that can be replicated to improve health outcomes for communities. It combined clinical and community approaches into a cohesive model to improve care and replicated in additional locales the success areas achieved in a pioneering community. Implementing this model of care in the communities of Manchester and Nashua was not without barriers. Manchester and Nashua are the two most urban and culturally diverse cities in New Hampshire. Both are home to large immigrant and refugee populations who speak a multitude of languages. Poverty rates are higher when compared to the rest of the state, and patients here are more likely to receive Medicaid or not have insurance when compared to other areas. These factors required the Million Hearts Learning Collaborative to be very thoughtful about its implementation approach.

Another barrier to implementation was developing NQF 0018 reporting functionality. MCHC, LHC-N, and Goodwin Community Health are federally qualified health centers, and thus are required to report on hypertension to the Health Resources and Services Administration using the Uniformed Data Set measure. Although this measure is similar to NQF 0018, it is not exact. Prior to implementing any piece of CMC/DHK’s model, the clinical sites needed to develop reporting for a different hypertension measure. While such a task on its own is not a challenge, it does have larger implications. There is an opportunity for two federal agencies to align reporting measures to minimize the reporting burden of clinical sites.

For many years, public health services have been provided in “silos,” based on traditional funding streams, while medical care has rarely extended beyond health care walls to the broader community. With the health care arena in rapid transition, it will be imperative to embrace a shift in traditional thinking to one that partners primary and preventive care with public health to support a system of community care coordination. Evidence-based public health interventions and sound referral systems will be components of the new terrain, leading to evidence-based, sustainable models of care. As the nation moves toward new ways of improving health, the integration of public health and primary care efforts present unique opportunities, like the New Hampshire Million Hearts Learning Collaborative.

References

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2013. BRFSS survey data and documentation. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2013.html (accessed January 6, 2016).

- CDC. 2015. Million hearts. Available at: http://millionhearts.hhs.gov/ (accessed January 6, 2016).

- Chrostowska, M., and K. Narkiewicz. 2010. Improving patient compliance with hypertension treatment: Mission possible? Current Vascular Pharmacology 8(6):804–7. https://doi.org/10.2174/157016110793563799

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. 2014. Team-based care to improve blood pressure control. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 47(1):100–102. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/publications/cvd-AJPM-recs-team-based-care.pdf (accessed July 17, 2020).

- Fedrizzi, R., and K. Persson. 2014. Ten steps for improving blood pressure control in New Hampshire: A practical guide for clinicians and community partners. Durham, NH: Cheshire Medical Center/Dartmouth-Hitchcock Keene and the University of New Hampshire. Available at: https://nhhealthylives.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Ten-Steps-to-Blood-Pressure-Control.pdf (accessed July 17, 2020).

- Kaiser Permanente. 2014. Know your numbers. Available at: https://healthy.kaiserpermanente.org/static/health/richmedia/video/content/diabetes/pdf/english/knowyournumbers.pdf (accessed January 6, 2016).

- National Quality Forum. 2016. About us. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/story/About_Us.aspx (accessed January 6, 2016).

- New Hampshire Division of Public Health Services. 2011. 2011 New Hampshire state health profile: Improving health, preventing disease, reducing costs for all. Concord, NH: New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.dhhs.nh.gov/dphs/documents/2011statehealthprofile.pdf (accessed February 25, 2016).

- New Hampshire Institute for Health Policy and Practice. 2011. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) report module. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/brfss.htm (accessed

March 9, 2016). - University of New Hampshire. 2015. Public health and health promotion projects and initiatives. Available at: http://chhs.unh.edu/ihpp/publications (accessed March 17, 2016).