Improving Access to Effective Care for People Who Have Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

Introduction

Mental health and substance use disorders affect people of all ages and demographics and are extremely burdensome to society. At least 18.1% of American adults experience some form of mental disorder, 8.4% have a substance use disorder, and about 3% experience co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders (SAMHSA, 2016). In 2013, health-related spending on mental health disorders in the United States was about $201 billion (Roehrig, 2016). Moreover, four of the top five sources of disability in people 18–44 years old are behavioral health conditions (WHO, 2001). While knowledge regarding recognition and treatment has steadily advanced, the public health effects of that knowledge have lagged. More effective and specific treatments exist now than in the past, and increased numbers of people who have these conditions can now lead productive, useful lives if they are treated properly.

Behavioral health is an essential component of overall health. People seen in primary care settings with chronic medical conditions—such as diabetes, asthma, and cardiovascular disorders—have a higher probability of having a substance use disorder or more common mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety disorders. Coexistence of mental health or substance use disorders with general medical conditions complicates the management of both.

People who have more severe behavioral health conditions—such as psychotic disorders, complex bipolar disorders, treatment-resistant depression, severe obsessive-compulsive disorder, and substance use disorders—commonly have or develop such medical problems as diabetes or heart disease and often die early, as much as two decades earlier than the general population.

Although behavioral health and overall health are fundamentally linked, systems of care for general medical, mental health, and substance use disorders are splintered. For historical, cultural, financial, and regulatory reasons, the three care systems operate separately from one another.

People who have co-occurring behavioral health and general medical conditions make up a high fraction of the so-called superuser group. The extra health care costs due to the co-occurrence of medical, mental health, and substance use disorders were estimated to be $293 billion in 2012 for all beneficiaries in the United States. Most of the increased cost for those who have comorbid mental health and substance use disorders is due to medical services, so there is a potential for substantial savings through integration of behavioral and medical services (Melek et al., 2014).

We have an “execution” problem and a “know-how” problem in the fields of mental health and substance use. Although for many conditions there is still a need to develop better and more effective personalized treatments, we do have effective treatments; but we have not been successful in getting these treatments to many of the people who can benefit from them. We often fail to identify, engage, and effectively treat people in primary care settings who are suffering from behavioral health conditions. People who have severe mental health and substance use disorders have difficulty in accessing effective primary and preventive care for chronic medical conditions. Yet, there are well-tested models for providing care for people who have common behavioral health conditions in primary care settings with support from behavioral health providers. And there are effective care models that provide integrated care for people who have complex behavioral health conditions in behavioral health settings with support from other medical care providers. In both cases, establishing a team approach fostered by an integrated care system and supported by effective use of technology needs to have high priority. We are not routinely applying accountability strategies that offer incentives to use these models. Execution is hampered by shortages and maldistribution of psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, counselors, and other providers that care for these populations. The stigma attached to these conditions, as is often perpetuated in the mass media, still presents a challenge to getting people the care that they need. And we have substantial knowledge gaps. Currently, available treatment approaches are not always effective, and many patients are not able to achieve optimal response. We need to develop more effective treatments and learn much more about tailoring treatments to individuals. We also need to develop better strategies for implementing effective programs across large and diverse health systems.

Barriers to Service Delivery and Coordination

Three key barriers to improving well-being and health outcomes for people who have behavioral health conditions and general medical conditions need to be addressed.

A Fragmented Care System

Most Americans who have both medical and behavioral health conditions must interact with separate, siloed systems: a medical care system, a mental health care system, and a substance use service system. Each system has its own culture, regulations, financial incentives, and priorities. Each focuses on delivering a specific set of services and overlooks key questions, such as, “How can I help this person to lead a productive, satisfying life?” “What is the full array of needs that must be addressed to make this person healthier and put him or her on a path to well-being?” Many small front-line agencies, offices, and organizations in primary care, mental health, and addiction are poorly run, poorly capitalized, and poorly staffed. They are struggling to adopt more modern approaches to patient care.

Amplifying the fragmentation is the failure to ensure that behavioral health is fully integrated into the mainstream of health information technology (HIT). Strong HIT is a cornerstone of effective coordinated and integrated care; it has the potential to enable the automated provision of outcome assessments to patients and to summarize data in practical formats to facilitate provider decision making, quality measurement, and improvement. However, behavioral health providers face key barriers of cost, sustainability, concern about privacy and information sharing in the context of behavioral health conditions, and regulation in implementing electronic health record (EHR) systems. Notably, the 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act—which promotes the adoption of EHRs in medical settings, authorizes financial incentives for HIT uptake, and defines minimum acceptable standards for EHR systems—excludes behavioral health organizations and nonphysician providers from eligibility for the HIT incentive payments and thus renders EHR implementation and sustainability prohibitively expensive for many of these providers.

Until our nation establishes shared accountability in culture and in practice and integrates the various elements of its care systems, good outcomes and value-based efficient service strategies are unlikely to be achieved.

An Undersized, Poorly Distributed, and Underprepared Workforce

The diversity of health care workers required to deliver effective care of Americans who have behavioral health and complex medical conditions includes professionals with a wide array of backgrounds and skills, including physicians, psychologists, nurses, mental health and substance use counselors, care managers and coordinators, and social workers. Our current workforce is undersized and inadequately resourced, and available providers often lack the specific skills and experience to offer effective evidence-based and integrated care. Racial, ethnic, and geographic diversity of the workforce is lacking, and there is extreme maldistribution of behavioral health professionals; people in rural and impoverished areas have limited access.

Psychiatry is the only medical specialty other than primary care in which the Association of American Medical Colleges has identified a physician shortfall, a deficit that will get progressively worse by 2025 if not addressed (IHS, 2015). According to the federal government, in 2013, the nation needed 2,800 more psychiatrists to address the gap (IHS, 2015, p. 11). But the psychiatry deficit is growing. For example, the number of psychiatrists per 10,000 of population decreased from 1.28 in 2008 to 1.18 in 2013 (Bishop et al., 2016). It is difficult to see how the current national infrastructure for psychiatry training would address the gap, inasmuch as only 1,373 medical school graduates matched to psychiatry in 2016 (NRMP, 2016). The number of PhD psychologists was virtually unchanged over the same period (Olfson, 2016). Similar trends persist for social workers and substance use counselors. The constant size of the mental health and substance use provider workforce is one factor that has made it so difficult for many people who have behavioral health needs to get access to services. One recent study found that two thirds of primary care physicians report that they cannot obtain referrals to psychiatrists for their patients in need (Roll et al., 2013). Workforce shortages exist in most areas of the country, but some locales have rather small numbers of trained professionals who are delivering behavioral health services.

Providers in different parts of our care system are not sufficiently incentivized to work efficiently as a coordinated team to identify, engage, and manage care effectively for people who have both medical and behavioral health conditions. Primary care doctors need to be effective in identifying mental health and substance use problems and in engaging patients to get the care that they need on a continuing basis. Similarly, behavioral health providers need to be prepared to identify medical problems faced by patients and either manage patients or link them to required medical care. Mental health and substance use providers often lack up-to-date training in delivery of empirically supported treatments. In addition to shortcomings in specific clinical skills, behavioral health providers often work in solo or small independent practices, and our training system has not prepared them to work effectively in teams or collaborative settings. Nor has our payment system offered incentives to encourage providers to work in these settings. Working in isolated practice settings also limits the adoption and implementation of integrated delivery approaches. In addition, reductions in public-sector programs, low percentage of commercial insurance premium attributable to behavioral health, and low market rates for these services help to keep the numbers of people entering these professions low and thereby limit access to care and the ability of providers to embrace and implement new technologies.

There are important needs and barriers regarding care for behavioral health conditions in children and youth—in whom these conditions typically emerge. There are clear benefits to early intervention, but effective treatments are often not implemented. The relative shortage of child psychiatrists serves as a major barrier to developing effective integrated care models for this population. And there are profound challenges at the other end of the age spectrum as a consequence of the growing number of older Americans and the high prevalence of chronic conditions in this population (IOM, 2012).

Finally, our health system has not made full use of new communication technologies, such as telehealth and mobile health, to leverage the capacity of the existing behavioral health workforce. New technologies are simplifying communication with patients and offering opportunities for real-time health monitoring of patients. A major barrier has been tensions regarding information sharing and confidentiality that are specific to clinical substance use and mental health data. Emerging technologies have the capacity to overcome those barriers and improve the productivity and effectiveness of the workforce, but it is crucial to integrate new technologies with other treatment approaches so that they do not constitute an extra burden but rather become a seamless part of practice that enhances outcomes.

Payment Models that Reinforce Care Silos and Fragmentation of Care

The dominant approach to medical care and behavioral health care reimbursement is to use a fee-for-service (FFS) system. Essential elements of integrated care (outreach, provider-to-provider consultation, and population management) are often not reimbursed. FFS payment does not provide the flexibility to implement needed coordinated care effectively. Moreover, the current FFS system does not sufficiently value payment for behavioral health services (which are generally cognitive and time-based, as opposed to procedure based).

In theory, bundled or capitated approaches can allow more flexibility in how resources are used by a provider and allow a broader team of professionals to coordinate the care of patients. However, the methods for implementing and pricing capitated payment arrangements are less than ideal for patients who have behavioral health conditions.

One barrier is that the wrong provider may be capitated. For example, if a physician group receives a fixed payment for managing the nonhospital care of patients, the effects of better treatment approaches on hospital use will not accrue to the provider. In the case of Medicaid, the capitated payment by a state government to a managed care organization might be distributed to individual providers by using FFS payment approaches; the actual provider has little flexibility to use the capitated payment to improve outcomes and efficiency.

One other substantial challenge in using reimbursement schemes to provide incentives to make care more effective is that the needs of patients who have behavioral health conditions can vary from one patient to another. Thus, capitated or bundled payments for patients who have behavioral health conditions need to be appropriately risk-adjusted to account for differences in the expected costs of care for different patterns of problems. McGuire shows that current risk-adjustment approaches are not sophisticated enough to pay providers the fair amount for high-need patients (McGuire, 2016). That failure can lead providers and payers who use capitated payment systems to discourage the enrollment of high-need patients in a practice or plan. More work is needed to ensure that risk adjustment creates proper incentives for enrolling and effectively treating patients who have behavioral health conditions. In addition, for these payment models to work, they must properly account for the real costs of caring for people who have behavioral health conditions. As noted earlier, behavioral health conditions are the most expensive at a societal level. But the proportion of direct health care costs for these conditions has dropped substantially over the last several decades and now only makes up about 3.5% of the costs of commercial plans and 7% of public payments (Frank et al., 2009; Mark et al., 2014, 2016).

Parity laws now require insurance coverage to have the same policies to guide payments for medical care as for behavioral health care, but there are tactics that payers can use to avoid having to care for the latter. For example, the presence of inadequate networks of behavioral health providers can push patients with behavioral health conditions away from a specific managed care organization. Moreover, many people in need of behavioral health care face additional barriers when they find that a large proportion of psychiatrists have opted out of accepting public and private insurance plans (Bishop et al., 2014; Boccuti et al., 2013). Of all physician specialists, psychiatrists are least likely to accept new Medicare patients. Only 64% of psychiatrists report that they accept new Medicare patients in their practices, whereas 53% report taking new patients who have private non-capitated insurance, and 44% take new Medicaid patients (Bishop et al., 2014). Thus, a large number of psychiatrists accept only new patients who have the capacity to pay higher fees out of pocket (Bishop et al., 2014; Boccuti et al., 2013).

Facilitators of Potential Improvements in Care

There are opportunities to overcome the barriers to effective care to improve the well-being of people who are coping with mental health disorders, substance use disorders, and medical care conditions. A new administration can take advantage of the opportunities both to improve outcomes for people who have those problems and to reduce the financial burden of the services that they need. Several key facilitators are described below.

Know-How

Effective Treatments

Abundant evidence demonstrates the acceptable efficacy of several pharmacologic, psychotherapeutic, and behavioral treatments for management of most mental health disorders. In addition, there is a substantial evidence base supporting the efficacy of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies for treatment for substance use disorders. Recent progress led to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of medications for treatment for smoking, alcohol use disorders, and opioid dependence. There are not yet FDA-approved pharmacotherapies for treatment for cannabis use disorder, stimulant use disorders (involving cocaine, amphetamine, or MDMA), or hallucinogen abuse disorders (involving ketamine, PCP, LSD, or psilocybin). With the possible exception of disulfiram (Antabuse) treatment for alcohol use disorders, which generates high rates of abstinence among fully adherent patients (the minority of treated patients), medications for addiction are more successful in reducing the intensity of use of the abused substance than in producing and sustaining abstinence. That finding has led to a growing focus on reducing the harm associated with substance use as a treatment objective that may complement that of attaining total abstinence. In addition, there are various group and individual therapeutic approaches and counseling strategies that have favorable effects on the lives of people who use such services. The growing recognition of the link between early life trauma, mental health, addiction, and poor health outcomes has led to increased interest in trauma-informed care. With the increasing evidence base, there is a need to develop, train in, and implement these approaches.

Effective Models of Care

Substantial investment in research and demonstrations has improved our understanding of what effective care is. Examples of models of care that have been demonstrated to be effective and scalable are collaborative-care models in primary care, integrated-care models in mental health clinics, team-based assertive community treatment programs for people who have severe mental health disorders, and early-intervention programs for first-episode psychosis.

The Current Imperative for Integration

Health care providers around the country have entered an era of business integration. Hospitals are merging, hospitals and physician practices are merging, and traditional medical care practices are affiliating more closely with mental health, substance use, long-term care, oral health, and social service providers. In part, the imperative for integration is driven by market forces that seem to encourage scale and scope in service offerings. But the integration imperative also has been encouraged by federal policy initiatives that have created financial incentives for providers to integrate, especially with a focus on services supported by Medicare and Medicaid.

Changing Approaches to Paying for Care

The first and foremost principle that has to be adopted is that payment by payers and provider agencies should be reasonable and adequate for evidence-based practices. If that simple principle is not observed, all other issues will remain difficult to solve.

In addition to integration, our national health system has been exploring a broad array of value-based payment systems that reward providers for good outcomes rather than for the volume of services provided. Experiments in changing incentives in payment systems are occurring among the three key types of payers: Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers.

Value-based approaches and bundled-payment models not only create better incentives to improve outcomes but allow flexibility to support nontraditional services or nontraditional providers that are central to integrated care. For example, Colorado-based Rocky Mountain Health Plans is testing whether a global payment model can support the provision of behavioral services in local primary care practices. Under the Sustaining Healthcare Across Integrated Primary Care Efforts pilot, which was launched in 2012, three practices in western Colorado that have already integrated behavioral health care are receiving global payments to pay for team-based care; three integrated practices that earn FFS payments are serving as controls.

Insurance Expansion and Medical Health Parity Laws

The large increase in the number of Americans now covered by health insurance because of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) facilitates improvements in the care of people who have complex conditions. And insurance policies offered in the ACA marketplaces are required to cover behavioral health services. Furthermore, recent health parity laws prevent insurers from placing greater financial requirements (such as copayments or treatment limits) on mental health services than are placed on medical care services in any insurance policy offered. Those laws will substantially expand financial access to a full array of behavioral health services.

Technology

Advances in technology have the potential to enhance access to and quality and cost efficiency of behavioral health and mental health care.

Electronic Health Records

Quality and cost efficiency of care rely on effective and efficient communication among providers and on the smooth flow of information into and among medical records. Similar benefits could derive from EHR use in behavioral and mental health, but their adoption has been notably slow. In fact, in comparison with the rapid rise in EHR use in general medical and primary care settings, less than 20% of behavioral health facilities have adopted EHRs (Walker et al., 2016). Reasons for slow adoption include concerns about information sharing and confidentiality that are specific to clinical substance use and mental health data and to the cost and affordability of HIT, particularly in small and widely disseminated practice settings, which have substantial financial barriers to adoption. To realize the benefits of HIT, innovative solutions are needed to address confidentiality issues and provide incentives for behavioral health providers to purchase and use the technology in ways that are integrated into general medical systems. Innovative solutions are also needed to make the EHR more efficient, more informative, and easier for providers to use.

Technology-Enabled Therapy for Behavioral and Mental Health

Technology-based therapies that patients can access with greater ease and at lower cost than face-to-face conventional psychotherapy have been developed, such as Mood Gym (Australia National University, 2016), Beating the Blues (2015), and ThisWayUp (2016) (Richards and Richardson, 2012). Although much work remains to optimize the application of the therapies in clinical settings, evidence suggests that with proper patient selection and appropriate strategies for successful engagement, patients who have less complicated psychiatric needs (such as for mild to moderate depression or anxiety) can derive clinical benefit at lower cost while overcoming the logistical hurdles to access, including basic availability of clinicians in a locale. Such online resources are rapidly expanding to cover a broad continuum from educational and self-help materials to modular offerings that emulate manualized evidence-based cognitive behavioral therapies.

Virtual visits provided by clinicians over the Internet improve access and outcomes principally by enhancing patient convenience. Compelling examples include geriatric patients who have mobility challenges and young patients who have autism and for whom transport to a doctor’s office can be difficult or even prohibitive. In such instances, the ability to hold a session by video conference can reduce cancellations and “no shows” and give clinicians a better window into behavior in the actual home context.

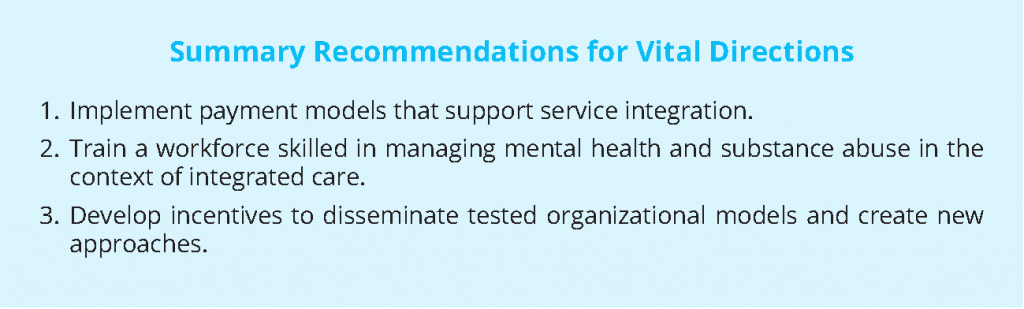

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

To improve the lives of people who have behavioral health and medical conditions, it is essential that public policy play important roles in changing the approach to delivering services to this population. The following three vital directions are critical for improving outcomes by increasing access to effective services:

- New payment approaches that recognize the costs of managing the care of patients who have complex conditions and that encourage the use of teams and technology to identify, engage, and manage the care of such patients.

- Investment in strategies and programs to expand, improve, diversify, and leverage—through technology and more efficient team-based approaches—the clinical workforce and to develop incentives to improve service in underserved areas.

- Development and implementation of clearly measurable standards to encourage dissemination of tested organizational models and to establish a culture of shared accountability to integrate the delivery of services.

Implement Payment Models That Support Service Integration

The current approach to paying for behavioral health care and general medical care will never lead providers to meet the needs of people for these types of care adequately. The emphasis is on payment for the volume of service provided, and incentives to push providers to focus on patients’ outcomes are not in place.

A first public-policy goal should be greater use of payment approaches that offer incentives to providers to improve outcomes by paying adequately for evidence-based services. Current trends toward more integration of service capacity among health care providers will make it more likely that the provider system will develop care approaches that meet the varied needs of people who are facing behavioral health challenges.

To design a payment system that works, we need a blend of policy strategies that create incentives for good care for the full array of patients who have behavioral health conditions:

- Payment models should encourage quality and value, as well as allow flexibility, so that providers can choose management strategies that will lead to the best possible outcomes. Through Medicare and Medicaid, the federal government can lead the way in the transition to value-based payment.

- People who have complex behavioral health and medical conditions should be specifically encouraged to enroll in Medicaid programs and exchange policies offered through the ACA.

- Payments should be risk-adjusted with sophisticated methods so that providers are paid appropriately to ensure that adequate resources flow to providers who care for the neediest in our population.

- Regulations to complement new reimbursement approaches should be implemented so that there is a level playing field for providers and so that delivery of adequate care will be guaranteed.

Such strategies should have high priority in the coming years and could lead to better outcomes and more efficient use of our medical care investment.

Train a Workforce Skilled in Managing Behavioral Health Conditions

The workforce needs to grow and diversify to meet the demand to engage and serve people who have mental health and substance use disorders more effectively. Access to insurance is growing, but insurance is not valuable if there are no providers to deliver needed services. The development of innovative organizational models for managing behavioral health conditions is laudable, but they will not be sufficiently implemented if there is not a workforce that understands and is trained to deliver services with the new models of care that have been tested in careful studies.

A new administration should give high policy priority to ensuring that our health-system workforce can deliver the services required to improve outcomes for people who have behavioral health conditions. Three policy approaches could contribute:

- Fund well-tested programs that could encourage new entry into the behavioral health services field. A wide array of federal programs supports the training of physicians and other traditional medical care providers, such as nurses and dentists. For example, the federal Bureau of Health Workforce oversees loan repayment programs for physicians and dentists, and scholarship programs are aimed at increasing the numbers of primary care physicians, dentists, and nurses. Those programs should be expanded and should focus on increasing the numbers of professionals who care for people who have mental health and substance use disorders.

- Provide opportunities for providers to learn principles of care coordination and of teamwork. Building an effective workforce to improve outcomes of people who have mental health and substance use disorders requires more than scaling up of the workforce. Public policies should also focus on new skills for members of the workforce. Educational programs directed at the skills needed to work in teams and the skills needed for effective care coordination are needed around the country. Similarly, primary care physicians need additional training to be comfortable in working collaboratively with providers of care for mental health and substance use disorders because they must often manage patients who have these conditions, especially patients whose disorders are mild to moderate.

- Spread use of new technologies that leverage the workforce. New technologies that can help leverage the skills of providers in this field are being developed each year. For example, telehealth technologies can link psychiatrists to primary care providers in rural areas who require help in diagnosing problems and developing treatment plans. Public policy should correct the failure to provide the needed incentives for behavioral health organizations and providers to invest in and use tools and information systems to “defragment” care and accelerate the development of new technologies that assist in managing behavioral health care. Federal policies should fund training to help the existing workforce to learn how to use technology more effectively to leverage the ability to treat as many patients as possible and as effectively as possible.

Develop Incentives to Disseminate Tested Organizational Models

A third vital direction for public policy in behavioral health is to fund improvements in know-how for building better care models, in organizational strategies, and in accountability to attain better outcomes.

Expand Investment to Develop, Evaluate, and Implement Behavioral Health Quality Measures

Better care models can be identified only when there are clear, routinely collected quality measures for tracking the effectiveness of health care integration. Several strategies could support development of measures at the interfaces between behavioral health care and general medical care:

- Expanding expectations for health systems to establish structural mechanisms for integration of mental health care, substance abuse care, and general health care. This could include expanding requirements for accreditation or recognition programs, such as Patient-Centered Medical Home, that focus on the population of people who have mild to moderate behavioral health conditions and are being seen in general medical settings.

- Expanding measures that focus on access to effective behavioral health care and behavioral health outcomes for patients in general medical care settings.

- Developing measures to assess access to preventive health services, primary care, and chronic-disease care for people in behavioral health care settings and to assess their associated outcomes.

Beyond specifically developing measurement strategies for integrated care, a lead agency should be identified that has responsibility, expertise, and resources for stewarding the field of behavioral health quality measurement to be held accountable for their development. In collaboration with other public and private stakeholders among the “six Ps”—patients, providers, practice organizations, payers, purchasers, and policy makers—that agency should develop a coordinated plan to implement this and the next two recommendations (Pincus et al., 2003).

Take Action to Overcome Barriers to Improve and Link Data Sources

Effective integration of behavioral health and general medical care must incorporate strategies to develop, implement, use, and coordinate HIT to meet the needs of consumers who have behavioral health conditions and of their health care providers and systems.

Gaps in standardizing and capturing behavioral health information must be addressed. For example, under the HITECH Act, SNOMED-CT and LOINC are mandated medical terminologies for the exchange of clinical information, but if these terminologies do not accommodate behavioral health needs, the goals of the act cannot be achieved. A recent Institute of Medicine report recommended incorporating evidence-based behavioral health psychosocial intervention in classification systems, such as Current Procedural Terminology (IOM, 2015). Policies and regulations should include specifications for standardizing behavioral HIT among different general medical, mental health, and substance use treatment settings to ensure data sharing and data transportability. More sophisticated information-exchange protocols are needed to address behavioral health privacy and security concerns. Vendors should be expected to develop EHRs that enable tagging of specific data elements with different privacy levels; this would be important for accommodating the use of consumer-driven technologies, such as mobile applications. Finally, behavioral health clinical organizations and nonphysician behavioral health providers will need funding (possibly as part of bundled payments) to assist in deploying and using HIT that meets specifications that the HITECH Act provided for hospitals and physicians.

Conduct Research to Develop the Evidence Necessary to Expand Our Treatment Armamentarium and Support a More Robust and Comprehensive Set of Standards and Measures

Standards and measures should be developed to

- Document the mechanisms underlying mental health and substance use conditions better.

- Develop and test new, more effective, safer treatments.

- Determine which treatments achieve the best outcomes for different types of patients, especially in the context of different comorbidities.

- Implement evidence-based treatments.

Collaboration among funding agencies and health care organizations should inform the development of a research agenda that could marry the goals of intervention development and testing with the needs of quality measurement and improvement at clinical, organizational, and policy levels.

Conclusions and Summary

We face substantial and enduring challenges to improve the lives of many Americans who cope with mental health and substance use disorders. Those disorders are often chronic, and recovery can be a lifelong process, but better outcomes and the potential for better life courses are within easy reach for our society. There are barriers to progress, but our nation is at a moment when there also are many facilitators that can help us to make striking progress in improving people’s lives. We have much of the know-how that is needed, and now we need to put the know-how into action.

It will take the energy and commitment of many parts of our society to improve outcomes for people who have mental health and substance use disorders, especially in the presence of other medical problems that these people commonly face. We need supportive, and supported, families, supportive workplaces, supportive health providers, and supportive communities. But public policy at the federal level can also play a role in leading progress in this social challenge.

Three vital directions are offered to guide efforts to improve behavioral health care across our nation:

- New payment approaches: Develop and apply new payment approaches that provide fair payments that recognize the costs of managing the care of patients who have interacting medical and behavioral health conditions and encourage the use of teams and technology to implement evidence-based strategies to identify, engage, and manage the care of such people effectively.

- Workforce development: Invest in strategies and programs to expand, improve, diversify, and leverage—through technology and more efficient team-based approaches—the clinical workforce and to develop incentives to improve service in underserved areas.

- Standards and incentives to disseminate tested organizational models: Encourage and invest in improvements in know-how for building better care models, clinical and organizational strategies, and accountability mechanisms to attain better outcomes. Measurable standards must be created to implement incentives to diffuse tested organizational models and establish a culture of shared accountability to integrate the delivery of services.

There are barriers that make progress difficult, but there are also clinical and policy strategies that hold potential for enabling striking progress in improving the lives of people who face these challenges. We have much of the know-how that is needed, but we need to put it into action.

References

- Australia National University. 2016. MoodGYM Training Program. Available at: https://moodgym.anu.edu.au/welcome (accessed June 29, 2016).

- Beating the Blues. 2015. Available at: http://www.beatingtheblues.co.uk/ (accessed June 29, 2016).

- Bishop, T. F., M. J. Press, S. K. Keyhani, and H. A. Pincus. 2014. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry 71(2):176-181. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862

- Bishop, T. F., J. K. Seirup, H. A. Pincus, and J. S. Ross. 2016. Population of US practicing psychiatrists declined, 2003–13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care. Health Affairs 25(7):1271-1277. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1643

- Boccuti, C., C. Swoope, A. Damico, and T. Neuman. 2013. Medicare Patients’ Access to Physicians: A Synthesis of the Evidence. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, December 13, 2013. Available at: http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-patientsaccess-to-physicians-a-synthesis-of-the-evidence/ (accessed August 24, 2016).

- Frank, R. G., H. H. Goldman, and T. G. McGuire. 2009. Trends in mental health cost growth: An expanded role for management? Health Affairs 28(3):649-659. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.649

- IHS Inc. 2015. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2013 to 2025. Prepared for the Association of American Medical Colleges. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13111.57764

- IOM. 2012. The mental health and substance use workforce for older adults: In whose hands? Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13400

- IOM. 2015. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: A framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/1901

- Mark, T.L., K.R. Levit, T. Yee, and C.M. Chow. 2014. Spending on mental and substance use disorders projected to grow more slowly than all health spending through 2020. Health Affairs 33(8):1407–1415. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0163

- Mark, T. L., T. Yee, K. R. Levit, J. Camacho-Cook, E. Cutler, and C. D. Carroll. 2016. Insurance financing increased for mental health conditions but not for substance use disorders, 1986-2014. Health Affairs 35(6):958-965. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0002

- McGuire, T. G. 2016. Achieving mental health care parity might require changes in payments and competition. Health Affairs 35(6):1029-1035. https://doi.org/10.1377/ hlthaff.2016.0012

- Melek, S. P., D. T. Norris, and J. Paulus. 2014. Economic impact of integrated medical-behavioral healthcare: Implications for psychiatry. Denver, CO: Milliman Inc.

- NRMP (National Resident Matching Program). 2016. Results and data: 2016 Main Residency Match®. Washington, DC: NRMP.

- Olfson, M. 2016. Building the mental health workforce capacity needed to treat adults with serious mental illnesses. Health Affairs 35(6):983-990. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1619

- Pincus, H. A., L. Hough , J. K. Houtsinger, B. L. Rollman, and R. G. Frank. 2003. Emerging models of depression care: Multi-level (‘6 P’) strategies. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 12(1):54-63. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.142

- Richards, D., and T. Richardson. 2012. Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 32(4):329-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.004

- Roehrig, C. 2016. Mental disorders top the list of the most costly conditions in the United States: $201 billion. Health Affairs 35(6):1130-1135. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1659

- Roll, J. M., J. K. Kennedy, M. Tran, and D. Howell. 2013. Disparities in unmet need for mental health services in the United States, 1997–2010. Psychiatric Services 64(1):80-82. Available at: https://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ps.201200071 (accessed July 28, 2020).

- SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2016. Mental and Substance Use Disorders. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/disorders (accessed June 29, 2016).

- This Way Up. 2016. Available at: https://thiswayup.org.au (accessed June 29, 2016).

- Walker, D., A. Mora, M. M. Demosthenidy, N. Menachemi, and M. L. Diana. 2016. Meaningful use of EHRs among hospitals ineligible for incentives lags behind that of other hospitals, 2009-2013. Health Affairs 35(3):495-501. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0924

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2001. Chapter 2: Burden of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. In The World Health Report 2001. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.