Health Professional Education Student Volunteerism amid COVID-19: How a diverse, interprofessional team of health students created a volunteer model to support essential workers

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted education around the world. Institutions from preschool through higher education have either halted or significantly altered how education is provided, and the repercussions from this shift have been extensive. Many parents, particularly working mothers, are now in the precarious position of homeschooling their children while maintaining full-time jobs. At the same time, campus closures have led to many health professional education (HPE) students completing their coursework from home [1], which has resulted in greater physical isolation from their peers and fewer opportunities to experience interprofessional education. Those in charge of creating curricula—who, themselves, have been left unsettled with new roles and responsibilities—have tended to focus on siloed rather than interprofessional experiences. However, pandemics—like other disasters—necessitate an interprofessional, cross-sectoral response, which is currently missing from the virtual HPE classroom [2]. With these challenges to in-person learning and interprofessional collaboration, many HPE students are looking to contribute to their communities in new ways by supporting essential workers, and this common goal has spurred multidisciplinary efforts. Amid the pandemic, HPE students are forming volunteer groups and working behind the scenes to mitigate burdens for essential workers and vulnerable populations. Future pandemic and natural disaster response plans will benefit from adapting HPE student models created during COVID-19.

HPE students around the world represent a unique set of learners who bridge the gap between education and practice. While they are not yet licensed to practice independently, they are aware of the burdens that health care workers (HCWs) face. These students make up a large, highly motivated, volunteer pool with diverse and valuable skill sets. Serving as administrative members of volunteer groups, HPE students can help advise risk mitigation strategies and serve as liaisons between crisis response experts and families in need [3]. For example, during the 2016 cholera outbreak in Yemen, trained HPE-student volunteers provided psychosocial support to children as they recovered from the illness and reintegrated into their communities [4]. Similarly, HPE students are volunteering their time during COVID-19. Over the past several months, students in the United States have stepped up to volunteer in call centers, organize personal protective equipment (PPE) drives, create patient education materials, help with grocery shopping, and assist with production of COVID-19 testing materials [3].

Local Action for Global Need

Globally, schools are the largest provider of childcare, and in March of 2020, an unprecedented 91.3 percent of pupils (1.6 billion children) were unable to attend class due to closures from physical distancing requirements [5]. School closures are particularly burdensome for essential workers, who—on top of unrivaled professional demands—now find themselves needing to report to work but without affordable childcare. Furthermore, due to illness, death, and psychological distress, many caregivers are unable to supervise their children during pandemics [4]. Many parents also struggle to afford childcare, with Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries spending 27 percent of the average worker’s wage on childcare for a two-year-old [6]. Globally, mothers are often forced to choose between childcare and their livelihoods. For example, over 70 percent of mothers in Kenya, Liberia, and Senegal report that the inability to afford childcare prevents them from contributing to the workforce [6].

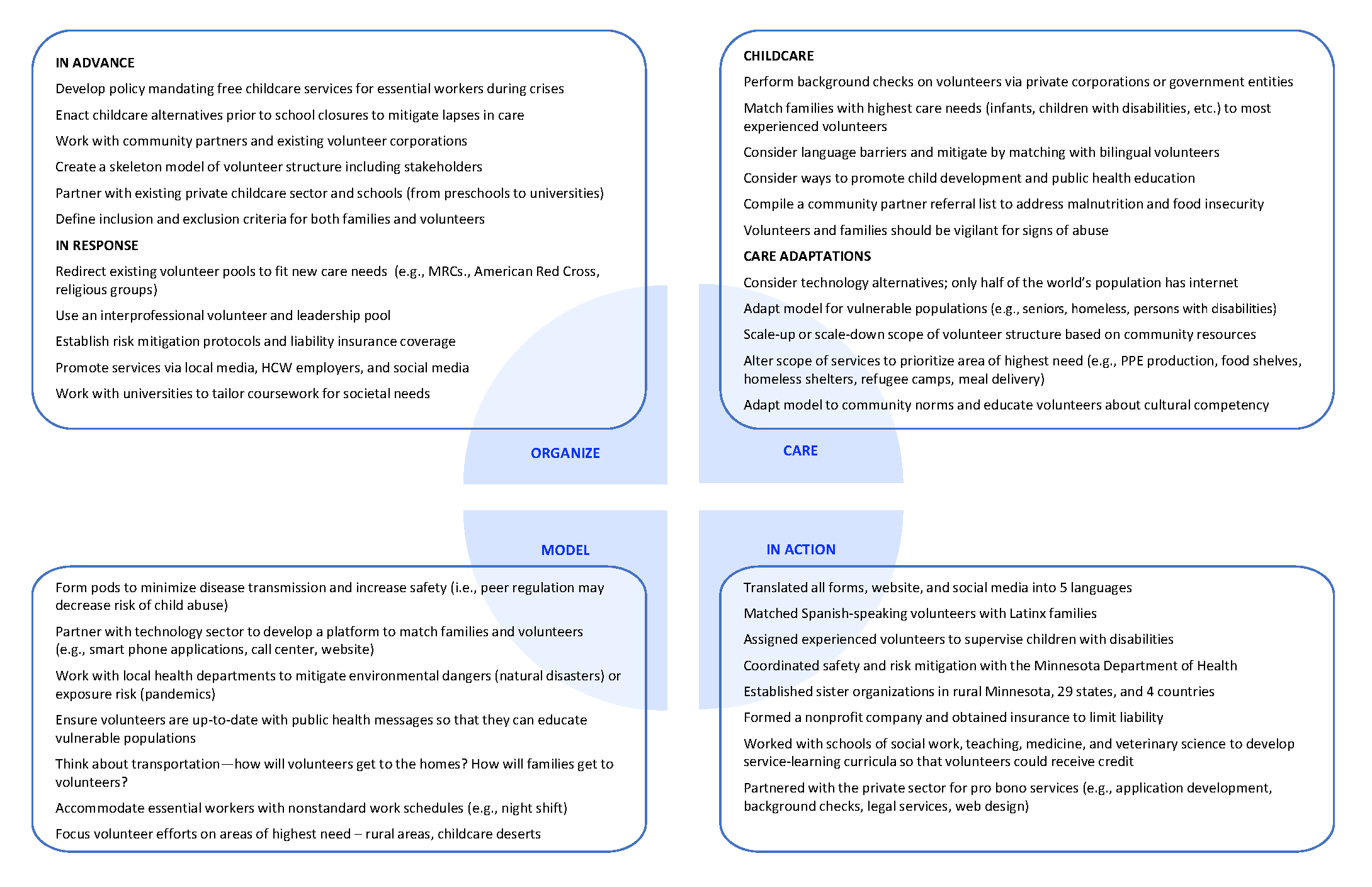

In Minnesota, a group of interprofessional health students recognized that lack of access to childcare is a bottleneck that prevents many essential workers from getting to work. COVID-19 exacerbated existing childcare inaccessibility in the state, where more than 20 percent of home-based daycare centers have closed over the past four years [7]. In an effort to increase alternative childcare options and support Minnesota health care families, HPE students formed a volunteer babysitting group. Over the course of two months, the students transformed their initially small volunteer pool into a much larger nonprofit corporation called MN CovidSitters [3]. Figure 1 is a schematic of the steps the students took in deciding upon their area of focus and acting upon an identified need.

Figure 1 | MN CovidSitters Organizational Model

SOURCE: Developed by authors

As the “In Action” portion of the figure describes, the nonprofit uses a web-based application to link interprofessional college and graduate student volunteers with HCW families to provide free babysitting, pet sitting, and errand-running services [3]. The group has incorporated interprofessionalism in almost every step of development and implementation—from using veterinary students for pet sitting to creating educational materials for families based on guidance from the University of Minnesota College of Education and Human Development. Using social media and the matching application, CovidSitters sister groups have developed nationally and internationally. Led by HPE students, these groups learn from each other and tailor their organizations accordingly. There are now 34 CovidSitters sister branches in the United States, England, Canada, and Sudan.

While the CovidSitters model was produced with childcare in mind, the technology can be adapted based on the immediate need of the community. For example, considering half of the world’s children rely on schools to provide at least one daily meal [8], the MN CovidSitters application can be used to match families in need with food shelves and meal delivery services. As described in the figure, there are many other ways to use the CovidSitters application, including elder care, homeless and refugee population support, PPE production, and coordination of food distribution.

Prioritizing Safety and Public Health

When forming any HPE volunteering model, safety must be the number one priority. Groups must work to mitigate disease transmission, ensure safety of their volunteers, and prevent child harm. Based on guidance from the Minnesota Department of Health, CovidSitters matches families with volunteers using a “pod” system. Each pod consists of 2–5 volunteers who are assigned to a particular family based on need, and volunteers work only in the household to which they have been assigned. This “pod” structure works particularly well for contact-tracing should a volunteer be exposed to COVID-19 while babysitting. The model can also be adapted for use in future pandemics, when isolation is necessary from an infectious disease perspective.

Because of the chaotic nature of pandemics and natural disasters, children—particularly those with communication difficulties and intellectual disabilities—have increased vulnerability. For example, following the 2005 hurricanes in Louisiana [9], the 2016 cholera outbreak in Yemen [4], and the 2015–16 Ebola Virus Disease outbreaks in Sierra Leone and Liberia [4], there were reports of increased sexual violence and child abuse—sometimes at the hands of volunteers. As such, volunteer groups must reduce the risk of harm by establishing inclusion criteria and appropriately screening prospective volunteers. MN CovidSitters requires volunteers to be up to date on immunizations, have a valid student identification card, and pass a background check. As noted in the graphic, background checks can be performed by government or private businesses, and volunteer groups should use their network to ask for reduced fees for these services.

HPE students can promote safety by serving as public health messengers while they volunteer in mutual aid groups. During school closures, governments are forced to innovate new ways to spread critical information to children [4], which presents an opportunity for HPE students to serve as public health liaisons. For example, students training to be social workers or child psychologists can devise and deliver safety messages, using their education to cater to children’s literacy levels. Partnering with local government officials and public school educators, HPE students can adapt safety information to their target audience, ensuring it is regionally and culturally appropriate. As described in the figure, MN CovidSitters translated social media messages into multiple languages and matched families with bilingual volunteers based on a child’s primary language.

Role of Universities

Most universities and communities have Medical Reserve Corps (MRCs) that plan and implement responses to pandemics and natural disasters. The exclusion of HPE students from the list of essential workers creates barriers for the implementation of volunteer group responses. Many COVID-19 HPE student volunteer groups have been absorbed and are now regulated by their university’s MRC, which enables them to benefit from the broader university’s built-in safety precautions and liability insurance. Although MN CovidSitters is not a school-sanctioned group, the organization was able to form a symbiotic relationship between the University of Minnesota, the Twin Cities community, essential workers’ families, and the Minnesota Department of Health. This collaboration of stakeholders was possible, in part, because the students fostered partnerships using communication skills that they had acquired while working as interprofessional members of care teams.

Though promoting altruism in HPE is debated [10], students are seeking antidotes to the feelings of powerlessness and uncertainty they are currently experiencing. Through their volunteer efforts, many HPE students are inadvertently receiving an informal education in public health and service learning. Universities can provide structure and longevity to these efforts by acknowledging and incorporating them into formal curricula. Catering coursework to pandemic and natural disaster responses confers a societal benefit; students are able to meet community needs while simultaneously learning how to prepare for future emergencies. In addition, curriculum centered on public health and social determinants of health amid COVID-19 may improve future patient care.

Conclusion

Though COVID-19 has created a milieu of barriers for HPE students, they have shown that they can, and will, contribute to the pandemic response by catering to societal needs—the largest of which is childcare. Volunteerism and HPE curriculum should not be mutually exclusive, especially during times of emergency and pandemic responses. Nonprofit groups like MN CovidSitters can serve as models, illustrating ways that groups of interprofessional HPE students can be put into action during future pandemics and natural disasters.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! #COVID19 has disrupted health care and education globally – but students are in a unique place to bridge the gap between education and practice. A new #NAMPerspective describes how volunteerism is a natural fit for these students: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007e

Tweet this! #COVID19 has disrupted health care and education globally – but students are in a unique place to bridge the gap between education and practice. A new #NAMPerspective describes how volunteerism is a natural fit for these students: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007e

![]() Tweet this! Globally, schools are the largest providers of childcare, and physical distancing due to #COVID19 has left many essential workers without care for their children. A new #NAMPerspectives details how health education students stepped in: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007e

Tweet this! Globally, schools are the largest providers of childcare, and physical distancing due to #COVID19 has left many essential workers without care for their children. A new #NAMPerspectives details how health education students stepped in: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007e

![]() Tweet this! By volunteering during #COVID19, “many health education students are inadvertently receiving an informal education in public health and service learning.” Read more about one particular volunteer group, MD CovidSitters, in a new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007e

Tweet this! By volunteering during #COVID19, “many health education students are inadvertently receiving an informal education in public health and service learning.” Read more about one particular volunteer group, MD CovidSitters, in a new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007e

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- Rose, S. 2020. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA 323(21):2131-2132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5227

- National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education. 2020. COVID-19 response and resources. Available at: https://nexusipe.org/covid-19 (accessed June 11, 2020).

- Redden, E. 2020. Stepping up and helping out. Inside Higher Ed. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/04/07/universities-andtheir-students-are-helping-coronavirus-responsemyriad-ways (accessed May 15, 2020).

- The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action. 2020. Guidance note: Protection of children during infectious disease outbreaks. Available at: https://alliancecpha.org/en/system/tdf/library/attachments/cp_during_ido_guide_0.pdf?fi le=1&type=node&id=30184 (accessed May 15, 2020).

- UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). 2020. Education: From disruption to recovery. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed May 15, 2020).

- Samman, E., E. Presler-Marshall, N. Jones, T. Bhatkal, C. Melamed, M. Stavropoulou, and J. Wallace. 2016. Women’s work: Mothers, children and the global childcare crisis. Overseas Development Institute. Available at: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinionfiles/10333.pdf (accessed May 15, 2020).

- Samuels, R. 2019. A Minnesota community wants to fix its child-care crisis. It’s harder than it imagined. The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/a-minnesotacommunity-wants-to-fix-its-child-care-crisis-itsharder-than-it-imagined/2019/12/24/0134b5d2-0b9b-11ea-aa77-66da131c8555_story.html (accessed June 10, 2020).

- World Food Programme. 2019. The impact of school feeding programmes. Available at: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000102338/download/?_ga=2.25735934.2133225107.1591554216-65340082.1591554216 (accessed June 10, 2020).

- National Sexual Violence Resource Center. 2006. Hurricanes Katrina/Rita and sexual violence: Report on database of sexual violence prevalence and incidence related to hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Available at: https://www.nsvrc.org/publications/nsvrc-publications/hurricanes-katrinarita-and-sexual-violence-report-database-sexual-vi (accessed June 11, 2020).

- Harris, J. 2018. Altruism: Should it be included as an attribute of medical professionalism? Health Professions Education 4(1):3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpe.2017.02.005.