Health Literacy and Health Education in Schools: Collaboration for Action

Introduction

This NAM Perspectives paper provides an overview of health education in schools and challenges encountered in enacting evidence-based health education; timely policy-related opportunities for strengthening school health education curricula, including incorporation of essential health literacy concepts and skills; and case studies demonstrating the successful integration of school health education and health literacy in chronic disease management. The authors of this manuscript conclude with a call to action to identify upstream, systems-level changes that will strengthen the integration of both health literacy and school health education to improve the health of future generations. The COVID-19 epidemic [10] dramatically demonstrates the need for children, as well as adults, to develop new and specific health knowledge and behaviors and calls for increased integration of health education with schools and communities.

Enhancing the education and health of school-age children is a critical issue for the continued well-being of our nation. The 2004 Institute of Medicine (IOM, now the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM]) report, Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion [27] noted the education system as one major pathway for improving health literacy by integrating health knowledge and skills into the existing curricula of kindergarten through 12th-grade classes. The NASEM Roundtable on Health Literacy has held multiple workshops and forums to “inform, inspire, and activate a wide variety of stakeholders to support the development, implementation, and sharing of evidence-based health literacy practices and policies” [37]. This paper strives to present current evidence and examples of how the collaboration between health education and health literacy disciplines can strengthen K–12 education, promote improved health, and foster dialogue among school officials, public health officials, teachers, parents, students, and other stakeholders.

This discussion also expands on a previous NAM Perspectives paper, which identified commonalities and differences in the fields of health education, health literacy, and health communication and called for collaboration across the disciplines to “engage learners in both formal and informal health educational settings across the life span” [1]. To improve overall health literacy, i.e., “the capacity of individuals to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” [42], it is important to start with youth, when life-long health habits are first being formed.

Another recent NAM Perspectives paper proposed the expansion of the definition of health literacy to include broader contextual factors, including issues that impact K–12 health education efforts like state rather than federal control of education priorities and administration, and subsequent state- or local-level laws that impact specific school policies and practices [39]. In addition to addressing individual needs and abilities, socio-ecological factors can impact a student’s health. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses a four-level social-ecological model to describe “the complex interplay” of (1) individuals (biological and personal history factors), (2) relationships (close peers, family members), (3) community (settings such as neighborhoods, schools, after-school locations), and (4) societal factors (cultural norms, policies related to health and education, or inequalities between groups in societies) that put one at risk or prevent him/her from experiencing negative health outcomes [11]. Also worth examining are protective factors that help children and adolescents avoid behaviors that place them at risk for adverse health and educational outcomes (e.g., self-efficacy, self-esteem, parental support, adult mentors, and youth programs) [21,59].

Recognizing the influence of this larger social context on learning and health can help catalyze both individual and community-based solutions. For example, students with chronic illnesses such as asthma, which can affect their school attendance, can be educated about the impact of air quality or housing (e.g., mold, mites) in exacerbating their condition. Students in varied locations and at a range of ages continue, often with the guidance of adults, to take health-related social action. Various local, national, and international examples illustrate high schoolers taking social action related to health issues such as tobacco, gun safety, and climate change [18,21,57].

By employing a broad approach to K–12 education (i.e., using combined principles of health education and health literacy), the authors of this manuscript foresee a template for the integration of skills and abilities needed by both school health professionals and children and parents to increase health knowledge for a lifetime of improved health [1,29,31].

The right measurements to evaluate success and areas that need improvement must be clearly identifed because in all matters related to health education and health literacy, it is vital to document the linkages between informed decisions and actions. Often, individuals are presumed to be making informed decisions when actually broader socio-ecological factors are predominant behavioral influences (e.g., an individual who is overweight but has never learned about food labeling and lives in a community where there are no safe places to be physically active).

Health Education in Schools

Standardized and broadly adopted strategies for how health education is implemented in schools—and by whom and on what schedule—is a continuing challenge. Although the principles of health literacy are inherently important to any instruction in schools and in community settings, the most effective way to incorporate those principles in existing and differing systems becomes a key to successful health education for children and young people.

The concept of incorporating health education into the formal education system dates to the Renaissance. However, it did not emerge in the United States until several centuries later [26]. In the early 19th century, Horace Mann advocated for school-based health instruction, while William Alcott also underscored the contributions of health services and the school environment to children’s health and well-being [17]. Public health pioneer Lemuel Shattuck wrote in 1850 that “every child should be taught early in life, that to preserve his own life and his own health and the lives of others, is one of the most important and abiding duties” [43]. During this same time, Harvard University and other higher education institutions with teacher preparation programs began including hygiene (health) education in their curricula.

Despite such early historical recognition, in the mid-1960s, the School Health Education Study documented serious disarray in the organization and administration of school health education programs [45]. A renewed call to action, several decades later, introduced the concepts of comprehensive school health programs and school health education [26].

From 1998 through 2014, the CDC and other organizations began using the term “coordinated school health programs” to encompass eight components affecting children’s health in schools, including nutrition, health services, and health instruction. Unfortunately, the term was not broadly embraced by the educational sector, and in 2014, CDC and ASCD (formerly the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development) unveiled the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) framework [36]. This framework has ten components, including health education, which aims to ensure that each student is healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged. Among the foundational tenets of the framework is ensuring that every student enters school healthy and, while there, learns about and practices a healthy lifestyle.

At its core, health education is defined as “any combination of planned learning experiences using evidence-based practices and/or sound theories that provide the opportunity to acquire knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to adopt and maintain healthy behaviors” [3]. Included are a variety of physical, social, emotional, and other components focused on reducing health-risk behaviors and promoting healthy decision making. Health education curricula emphasize a skills-based approach to help students practice and advocate for their health needs, as well as the needs of their families and their communities. These skills help children and adolescents find and evaluate health information needed for making informed health decisions and ultimately provide the foundation of how to advocate for their own well-being throughout their lives.

In the last 40 years, many studies have documented the relationship between student health and academic outcomes [29,40,41]. Health-related problems can diminish a student’s motivation and ability to learn [4]. Complications with vision, hearing, asthma, occurrences of teen pregnancy, aggression and violence, lack of physical activity, and low cognitive and emotional ability can reduce academic success [4].

To date, there have been no long-term sequential studies of the impact of K–12 health education curricula on health literacy or health outcomes. However, research shows that students who participate in health education curricula in combination with other interventions as part of the coordinated school health model (i.e., physical activity, improved nutrition, and/or family engagement) have reduced rates of obesity and/ or improved health-promoting behaviors [25,30,34]. In addition, school health education has been shown to prevent tobacco and alcohol use and prevent dating aggression and violence. Teaching social and emotional skills improves the academic behaviors of students, increases motivation to do well in school, enhances performance on achievement tests and grades, and improves high school graduation rates.

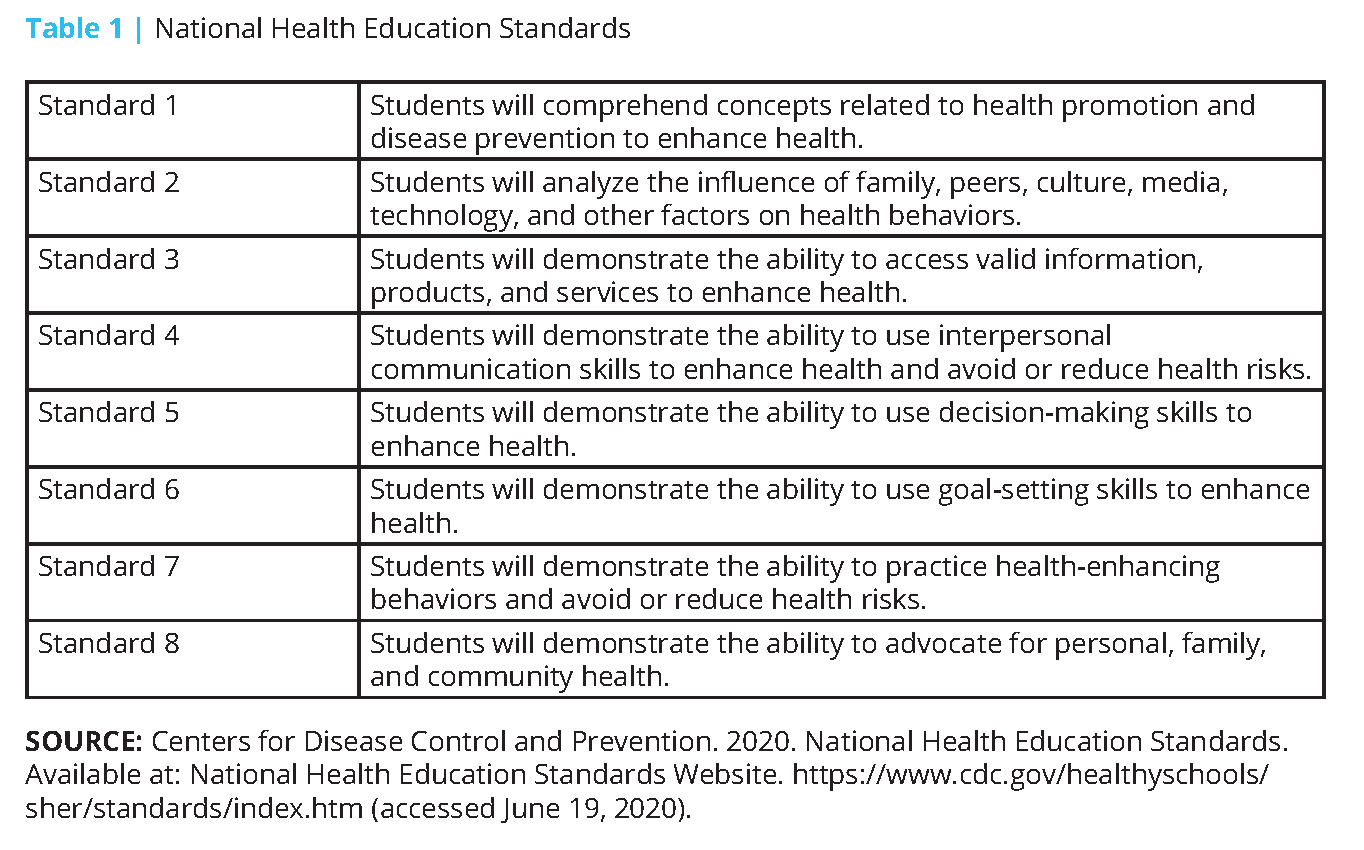

As with other content areas, it is up to the state and/or local government to determine what should be taught, under the 10th Amendment to the US Constitution [48]. However, both public and private organizations have produced seminal documents to help guide states and local governments in selecting health education curricula. First published in 1995 and updated in 2004, the National Health Education Standards (NHES) framework comprises eight health education foundations for what students in kindergarten through 12th grade should know and be able to do to promote personal, family, and community health (see Table 1) [12]. The NHES framework serves as a reference for school administrators, teachers, and others addressing health literacy in developing or selecting curricula, allotting instructional resources, and assessing student achievement and progress. The NHES framework contains written expectations for what students should know and be able to do by grades 2, 5, 8, and 12 to promote personal, family, and community health.

The Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH) model, which was first developed in the late 1980s with funds by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, serves to implement the NHES framework and was the largest school-based health promotion study ever conducted in the United States. CATCH has 25 years of continuous research and development of its programs [24] and aligns with the WSCC framework. Individualized programs like the CATCH model develop programming based on the NHES framework at the local level, so that local control still exists, but the mix and depth of topics can vary based on need and composition of the community.

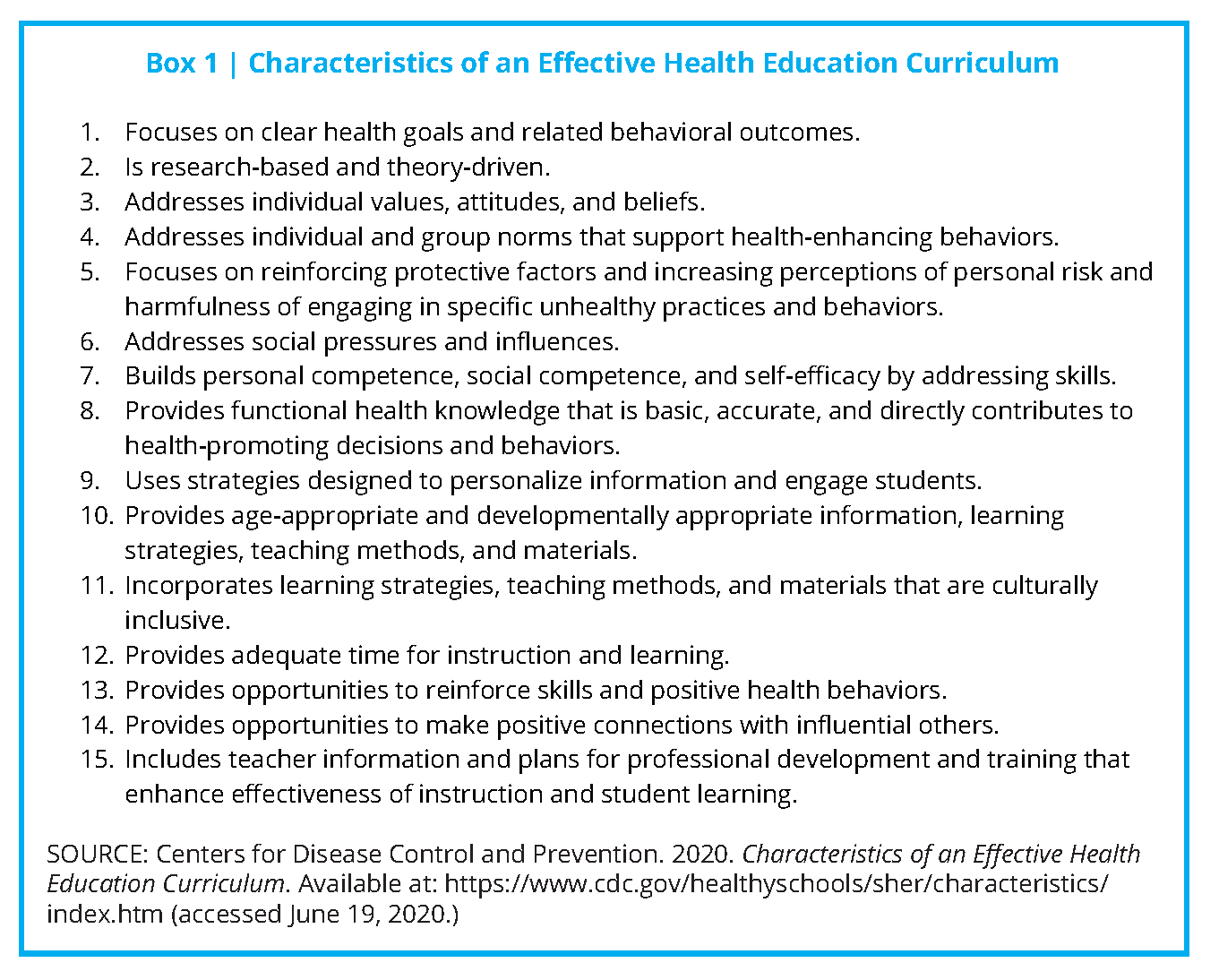

Based on reviews of effective programs and curricula and experts in the field of health education, CDC recommends that today’s state-of-the-art health education curricula emphasize four core elements: “Teaching functional health information (essential knowledge); shaping personal values and beliefs that support healthy behaviors; shaping group norms that value a healthy lifestyle; and developing the essential health skills necessary to adopt, practice, and maintain health enhancing behavior” [13]. In addition to the 15 characteristics presented in Box 1, the CDC website has more detailed explanations and examples of how the statements could be put into practice in the classroom. For example, a curriculum that “builds personal competence, social competence, and self-efficacy by addressing skills” would be expected to guide students through a series of developmental steps that discuss the importance of the skill, its relevance, and relationship to other learned skills; present steps for developing the skill; model the skill; practice and rehearse the skill using real-life scenarios; and provide feedback and reinforcement.

In addition, CDC has developed a Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool [14] to help schools conduct an analysis of health education curricula based on the NHES framework and the Characteristics of an Effective Health Education Curriculum.

Despite CDC’s extensive efforts during the past 40 years to help schools implement effective school health education and other components of the broader school health program, the integration of health education into schools has continued to fall short in most US states and cities. According to the CDC’s 2016 School Health Profiles report, the percentage of schools that required any health education instruction for students in any of grades 6 through 12 declined. For example, 8 in 10 US school districts only required teaching about violence prevention in elementary schools and violence prevention plus tobacco use prevention in middle schools, while instruction in only seven health topics was required in most high schools [6].

Although 8 of every 10 districts required schools to follow either national, state, or district health education standards, just over a third assessed attainment of health standards at the elementary level while only half did so at the middle and high school levels [6]. No Child Left Behind legislation, enacted in 2002, emphasized testing of core subjects, such as reading, science, and math, which resulted in marginalization of other subjects, including health education [22,31]. Academic subjects that are not considered “core” are at risk of being eliminated as public school principals and administrators struggle to meet adequate yearly progress for core subjects, now required to maintain federal funding.

In addition to the quality and quantity of health education taught in schools, there are numerous problems related to those considered qualified to provide instruction [5,7]. Many school and university administrators lack an understanding of the distinction between health education and physical education (PE) [9,16,19] and consider PE teachers to be qualified to teach health education. Yet the two disciplines differ regarding national standards, student learning outcomes, instructional content and methods, and student assessment [5]. Kolbe notes that making gains in school health education will require more interdisciplinary collaboration in higher education (e.g., those training the public health workforce, the education workforce, school nurses, pediatricians) [29]. Yet faculty who train various school health professionals usually work within one university college, focus on one school health component, and affiliate with one national professional organization. In addition, Kolbe notes that health education teachers in today’s workforce often lack support and resources for in-service professional development.

Promising Opportunities for Strengthening School Health Education

Comprehensive health education can increase health literacy, which has been estimated to cost the nation $1.6 to $3.6 trillion dollars annually [54]. The National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) includes the goal to “Incorporate accurate, standards-based, and developmentally appropriate health and science information and curricula in childcare and education through the university level” [49].

HHS’s Healthy People Framework presents another significant opportunity for tracking health in education as well as health literacy. The Healthy People initiative launched officially in 1979 with the publication of Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention [50]. This national effort establishes 10-year goals and objectives to improve the health and well-being of people in the United States. Since its inception, Healthy People has undertaken extensive efforts to collect data, assess progress, and engage multi-stakeholder feedback to set objectives for the next ten years. The Healthy People 2020 objectives were self-described as having input from public health and prevention experts, a wide range of federal, state, and local government officials, a consortium of more than 2,000 organizations, and perhaps most importantly, the public” [51]. In addition to other

childhood and adolescent objectives (e.g., nutrition, physical activity, vaccinations), Healthy People 2020 specified social determinants as a major topic for the first time. A leading health indicator for social determinants was “students graduating from high school within 4 years of starting 9th grade (AH-5.1)” [52]. The Secretary’s Advisory Committee report on the Healthy People 2030 objectives includes the goal to “eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all” [53]. The national objectives are expected to be released in summer 2020 and will help catalyze “leadership, key constituents, and the public across multiple sectors to take action and design policies that improve the health and well-being of all” [53].

In terms of supports in federal legislation, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015 recognized health education as a distinct discipline for the first time and designated it as a “well-rounded” education subject [2,22]. According to Department of Education guidelines, each state must submit a plan that includes four academic indicators that include proficiency in math, English, and English-language proficiency. High schools also must use their graduation rates as their fourth indicator, while elementary and middle schools may use another academic indicator. In addition, states must specify at least one nonacademic indicator to measure school quality or school success, such as health education. Under the law, federal funding also is available for in-service instruction for teachers in well-rounded education subjects such as health education. These two items open additional pathways for both identifying existing or added programs and having the capacity to collect data.

While several states have chosen access to physical education, physical fitness, or school climate as their nonacademic indicators of school success, the majority (36 states and the District of Columbia) have elected to use chronic absenteeism [2]. Given the underlying causal connection between student health and chronic absenteeism, absenteeism as an indicator represents a significant opportunity to raise awareness of chronic health conditions or other issues (e.g., student social/emotional concerns around bullying, school safety) that contribute to absenteeism. It also represents a significant opportunity for schools to work with stakeholders to prevent and manage such health conditions through school health education and other WSCC strategies to improve school health. Educators are more likely to support comprehensive health education if they are made aware of its immediate benefits related to student learning (e.g., less disruptive behavior, improved attention) and maintaining safe social and emotional school climates [31].

In an assessment of how states are addressing WSCC, Child Trends reported that health education is either encouraged or required for all grades in all states’ laws, with nutrition (40 states) and personal health (44 states) as the most prominent topics [15]. However, the depth and breadth of such instruction in schools is not known, nor if health education is being taught by qualified teachers. In 25 states, laws address or otherwise incorporate the NHES as part of the state health education curriculum.

The authors’ review of state 2017–2018 ESSA plans, analyzed by the organization Cairn, showed nine states that have specifically identified health education as one of its required well-rounded subjects (Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Nevada, North Dakota, and Tennessee) [8]. Cairn recommends that most states include health education and physical education in state accountability systems, school report card indicators, school improvement plans, professional development plans, needs assessment tools, and/or prioritized funding under Title IV, Part A.

In 2019, representatives of the National Committee on the Future of School Health Education, sponsored by the Society for Public Health Education (SOPHE) and the American School Health Association (ASHA), published a dozen recommendations for strengthening school health education [5,31,55]. The recommendations addressed issues such as developing and adopting standardized measures of health literacy in children and including them in state accountability systems; changing policies, practices, and systems for quality school health education (e.g., establishing Director of School Health Education positions in all state and territory education agencies tasked with championing health education best practices, and holding schools accountable for improving student health and wellbeing); and strengthening certification, professional preparation, and ongoing professional development in health education for teachers at both the elementary and secondary levels. Recommendations also call for stronger alignment and coordination between the public health and education sectors. The committee is now moving ahead on prioritizing the recommendations and developing action steps to address them.

Integrating Youth Health Education and Health Literacy: Success Stories

Minnesota Statewide Model: Integrating School Health Education and Health Literacy Through Broad Partnership

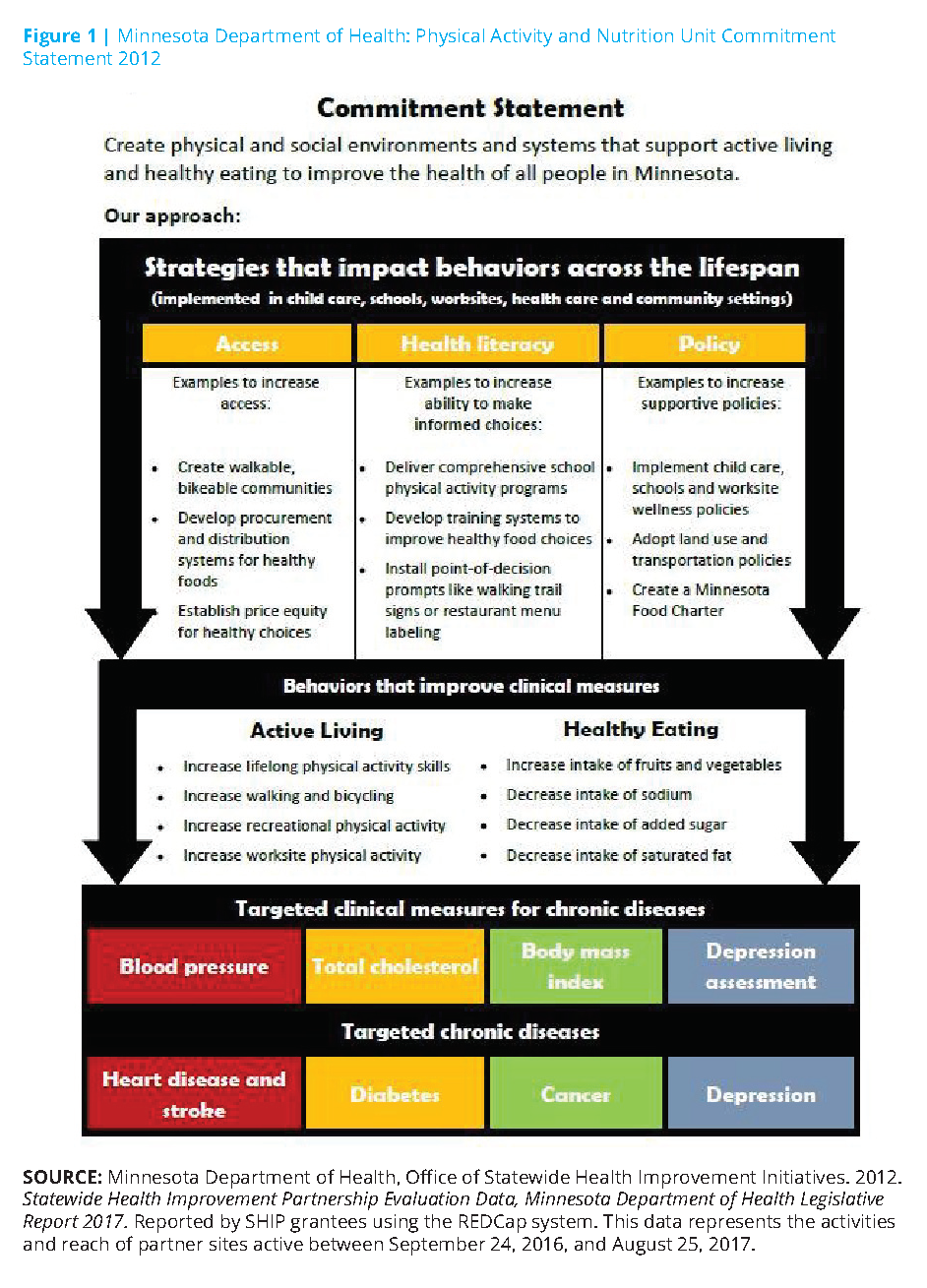

The Roundtable on Health Literacy held a workshop on health literacy and public health in 2014, with examples of how state health departments are addressing health literacy in their states [28]. One recent example of a strong collaboration between K–12 education and public health agencies is the Statewide Health Improvement Partnership (SHIP) within the Minnesota Department of Health’s Office of Statewide Health Initiative [35].

SHIP was created by a landmark 2008 Minnesota health reform law. The law was intended to improve the health of Minnesotans by reducing the risk factors that lead to chronic disease. The program funds grantees in all of the state’s 87 counties and 10 tribal nations to support the creation of locally driven policies, systems, and environmental changes to increase health equity, improve access to healthy foods, provide opportunities for physical activity, and ensure a tobacco-free environment [35]. Local public health agencies collaborate with partners including schools, childcare settings, workplaces, multiunit housing facilities, and health care centers through SHIP.

SHIP models the integration of (1) law, (2) policy, (3) goal-setting, and (4) resource building and forging some 2,000 collaborative partnerships and measuring outcomes. SHIP sets a helpful example for others attempting to create synergies across the intersections of state government, health education, local communities, and private organizations. The principles of health literacy are within these collaborations.

Grantees throughout the state have received technical assistance and training to improve school nutrition and physical activity strategies (see Figure 1). SHIP grantees and their local school partner sites set goals and adopt best practices for physical education and physical activity inside and outside the classroom. They improve access to healthy food environments through locally sourced produce, lunchrooms with healthier food options, and school-based agriculture. In 2017, SHIP grantees partnered with 995 local schools and accounted for 622 policy, systems, and environmental changes.

Minnesota has also undertaken a broad approach to health literacy by educating stakeholders and decision-makers (i.e., administrators, food service and other staff, students, community partners, and parents) about various health-related social and environmental issues to reduce students’ chronic disease risks.

SHIP grantees assist in either convening or organizing an established school health/wellness council that is required by USDA for each local education agency participating in the National School Lunch Program and/or School Breakfast Program [46,47]. A local school wellness policy is required to address the problem of childhood obesity by focusing on nutrition and physical activity. SHIP also requires schools to complete an assessment that aligns with the WSCC model and provides annual updates. Once the assessment is completed by a broad representation of stakeholders, SHIP grantees assist schools in prioritizing and working toward annual goals. The goal-setting and assessment and goal-setting cycle is continuous.

The Bigger Picture: A Case Study of Community Integration of Health Education and Health Literacy

Improving the health literacy of young people not only influences their personal health behaviors but also can influence the health actions of their peers, their families, and their communities. According to the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study funded by the CDC and the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases, from 2002 to 2012, the national rate of new diagnosed cases of Type 2 diabetes increased 4.8% [32]. Among youth ages 10-19, the rate of new diagnosed cases of Type 2 diabetes rose most sharply in Native Americans (8.9%) (although not generalizable to all Native American youth because of small sample size), compared to Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders (8.5%), non-Hispanic blacks (6.3%), Hispanics (3.1%), and non-Hispanic whites (0.6%).

Since 2011, Dean Schillinger, Professor of Medicine in Residence at the University of California San Francisco and Chief of the Diabetes Prevention and Control Program for the California Department of Public Health, has led a capacity-building effort to address Type 2 diabetes [23,28,44].

This initiative called The Bigger Picture (TBP) has mobilized collaborators to create resources by and for young adults focused on forestalling and, hopefully, reversing the distressing increase in pediatric Type 2 diabetes by exposing the environmental and social conditions that lead to its spread. Type 2 diabetes is increasingly affecting young people of color, and TBP is specifically developed by and directed to them.

TBP seeks to increase the number of well-informed young people who can participate in determining their own lifelong health behaviors and influencing those of their friends, families, communities, and their own children. The project aims to create a movement that changes the conversation about diabetes from blame-and-shame to the social drivers of the epidemic [23].

TPB is described by the team that created it as a “counter-marketing campaign using youth-created, spoken-word public services announcements to reframe the epidemic as a socio-environmental phenomenon requiring communal action, civic engagement, and norm change” [44]. The research team provides a description of questionnaire responses to nine of the public service announcements in the context of campaign messages, film genre and accompanying youth value, participant understanding of fi lm’s public health message, and the participant’s expression of the public health message. The investigators also correlate the responses with dimensions of health literacy such as conceptual foundations, functional health literacy, interactive health literacy, critical skills, and civic orientation.

One of the campaign partners, Youth Speaks, has created a toolkit to equip and empower students and communities to become change agents in their respective environments, raising their voices and joining the conversation about combating the spread of Type 2 diabetes [56].

In a discussion of qualitative evaluations of TBP and what low-income youth “see,” Schillinger et al. note that “TBP model is unique in how it nurtures and supports the talent, authenticity, and creativity of new health messengers: youth whose lived experience can be expressed in powerful ways” [44].

COVID-19: Health Crisis Affecting Children and their Families and a Need for Health Education and Health Literacy in K-12

In a recent op-ed, Rebecca Winthrop, co-director of the Center for Universal Education and Senior Fellow of Global and Economic Development of the Brookings Institution asked, “COVID-19 is a health crisis. So why is health education missing from school work?” [58] She notes that “helping sustain education amid crises in over 20 countries, I’ve learned that one of the first things you do, after finding creative ways to continue educational activities, is to incorporate life-saving health and safety messages.” Her call is impassioned for age-appropriate, immediately available resources on COVID-19 that can be easily incorporated into distance lesson plans for both children and families. Many organizations, such as Child Trends, are curating collections of such resources. Framing these materials using principles of health literacy and incorporating them into health education messages and resources may

be an ideal model for incorporating new pathways for public health K–12 learning.

Call to Action for Collaboration

Strategic and dedicated efforts are needed to bridge health education and health literacy. These efforts would foster the expertise to provide students with the information needed to access and assess useful health information, and to develop the necessary skills for an emerging understanding of health.

Starting with students in school settings, learning to be health literate helps overcome the increased incidence of chronic diseases such as Type 2 diabetes, and imbues a sense of self-efficacy and empowerment through health education. It also sets the course for lifelong habits, skills, and decision making, which can also influence community health.

Pursuing institutional changes to reduce disparities and improve the health of future generations will require significant collaboration and quality improvement among leaders within health education and health literacy. Recommendations provided in previous reports such as IOM’s 1997 report, Schools and Health: Our Nation’s Investment [26]; the 2004 IOM report on Health Literacy [27]; and the 2010 National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy [49] should be revisited. More recently, a November 2019 Health Literacy Roundtable Workshop (1) explored the necessity of developing health literacy skills in youth, (2) examined the research on developmentally appropriate health literacy milestones and transitions and measuring health literacy in youth, (3) described programs and policies that represent best practices for developing health literacy skills in youth, and (4) explored potential collaborations across disciplines for developing health literacy skills in youth [38]. With its resulting report, the information provided in the workshop should provide additional insights into collaborations needed to reduce institutional barriers to youth health literacy and empowerment.

At the national level, representatives from public sector health and education levels (e.g., HHS’s Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, Department of Education) can collaborate with school-based nongovernmental organizations (e.g., SOPHE, ASCD, ASHA, National Association of State Boards of Education, School Superintendents Association, Council of Chief State School Officers, Society of State Leaders of Health and Physical Education) to provide data and lead reform efforts. Leaders of higher education (e.g., Association of American Colleges and Universities, Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health) can join with philanthropies and educational scholars to pursue curricular reforms and needed research to further health education and health literacy as an integral component of higher education.

Among the approaches needed are (1) careful incorporation of key principles of leadership within systems; (2) the training and evaluation of professionals; (3) finding and sharing replicable, effective examples of constructive efforts; and (4) including young people in the development of information and materials to ensure their accessibility, appeal, and utility. Uniting the wisdom, passion, commitment, and vision of the leaders in health literacy and health education, we can forge a path to a healthier generation.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! A lifetime of improved health starts with educating children about their health and introducing health literacy early. A new #NAMPerspectives provides upstream and systems-level interventions to integrate health education into every classroom: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007b

Tweet this! A lifetime of improved health starts with educating children about their health and introducing health literacy early. A new #NAMPerspectives provides upstream and systems-level interventions to integrate health education into every classroom: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007b

![]() Tweet this! Standardized strategies for how health education is implemented in schools is a challenge. Authors of our newest #NAMPerspectives propose integrated strategies that can improve the health and health literacy of all students: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007b

Tweet this! Standardized strategies for how health education is implemented in schools is a challenge. Authors of our newest #NAMPerspectives propose integrated strategies that can improve the health and health literacy of all students: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007b

![]() Tweet this! A new #NAMPerspectives discussion paper examines case studies from across the nation that successfully coupled education in health literacy to robust general health education. Read more: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007b

Tweet this! A new #NAMPerspectives discussion paper examines case studies from across the nation that successfully coupled education in health literacy to robust general health education. Read more: https://doi.org/10.31478/202007b

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- Allen, M., E. Auld, R. Logan, J. Henry Montes, and S. Rosen. 2017. Improving collaboration among health communication, health education, and health literacy. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201707c

- Alliance for a Healthier Generation. 2018. Every Student Succeeds Act Frequently Asked Questions. Available at: https://www.healthiergeneration.org/sites/default/files/documents/20180814/3beb1de8/ESSA-FAQ.pdf (accessed May 3, 2020).

- American Association for Health Education. 2012. Report of the 2011 Joint Committee on Health Education and Promotion Terminology. American Journal of Health Education 43:sup2, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2012.11008225

- Basch, C. E. 2011. Healthier students are better learners: A missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. Journal of School Health 81:593-598. Available at: https://healthyschoolscampaign.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/AMissing-Link-in-School-Reforms-to-Closethe-Achievement-Gap.pdf (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Birch, D. A., S. Goekler, M. E. Auld, D. K. Lohrmann, and A. Lyde. 2019. Quality assurance in teaching K–12 health education: Paving a new path forward. Health Promotion Practice 20(6):845-857. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919868167

- Brener, N. D., Z. Demissie, T. McManus, S. L. Shanklin, B. Queen, and L. Kann. 2017. School Health Profiles 2016: Characteristics of Health Programs Among Secondary Schools. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/profiles/pdf/2016/2016_Profiles_Report.pdf (accessed May 18, 2020).

- McCormack Brown, K. R. 2013. Health education in higher education: What is the future? American Journal of Health Education 44(5):245-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2013.807755

- Cairn. 2020. State ESSA Plans. Available at: http://www.cairnguidance.com/essa-plans/ (accessed May 3, 2020).

- Cardina, C. 2014. Academic majors and subject-area certifications of health education teachers in the United States, 2011-2012. Journal of Health Education Teaching 5(1):35-43. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1085288 (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/ (accessed June 17, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2015. Principles of community engagement, 2nd ed. Atlanta, GA: CDC/ATSDR Committee on Community Engagement. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/index.html (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2019a. National Health Education Standards Website. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/standards/index.htm (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2019b. Characteristics of an Effective Health Education Curriculum Website. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/characteristics/index.htm (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019c. Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool (HECAT). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/hecat/index.htm (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Child Trends. 2019. State statutes and regulations for healthy schools: Health education. Available at: https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/WSCC-State-Policy-Health-Education.pdf (accessed May 28, 2019).

- Cobb, R. S. 1981. Health Education…A separate and unique discipline. Journal of School Health 51(9):603-604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1981.tb02243.x.

- Cottrell, R. R., J. T. Girvan, J. F. McKenzie, and D. Seabert. 2018. Principles and Foundations of Health Promotion and Education, 7th ed. Pearson: New York.

- Dubb, S. 2019. Parkland Students Outline Gun Safety Vision in Comprehensive Plan. Nonprofit Quarterly. Available at: https://nonprofi tquarterly.org/parkland-students-outline-gun-safety-vision-in-comprehensive-plan/ (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Goodwin, S. C. 1993. Health and physical education—Agonists or antagonists? Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 64(7):74-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1993.1060679

- Gould, L., E. Mogford, and A. DeVoght. 2010. Successes and Challenges of Teaching the Social Determinants of Health in Secondary Schools: Case Examples in Seattle, Washington. Health Promotion Practice 11(3):26S-33S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839909360172

- Guhne, J. 2001. Students send magazines’ tobacco ads back to publishers in “Don’t Buy” effort. Baltimore Sun. Available at: https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-2001-04-12-0104120141-story.html (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Hampton, C., A. Alikhani, M. E. Auld, and V. White. 2017. Advocating for Health Education in Schools (Policy brief). Society for Public Health Education: Washington, DC. Available at: https://www.sophe.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ESSAPolicy-Brief.pdf (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Hoffman, A. 2016. In San Francisco, the fight against diabetes gets personal: A local doctor tries to raise awareness about the social causes of Type 2 diabetes, in his community and others. CityLab. Available at: https://www.citylab.com/life/2014/11/in-san-francisco-the-fight-against-diabetes-getspersonal/382275/ (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Hoelscher, D. M., H. A. Feldman, C. C. Johnson, L. A. Lytle, S. K. Osganian, G. S. Parcel, S. H. Kelder, E. J. Stone, and P. R. Nader. 2004. School-based health education programs can be maintained over time: Results from the CATCH Institutionalization study. Preventive Medicine 38(5):594-606. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743503003311 (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Hoelscher, D. M., A. E. Springer, N. Ranjit, C. L. Perry, A. E. Evans, M. Stigler, and S. H. Kelder. 2010. Reductions in child obesity among disadvantaged school children with community involvement: The Travis County CATCH Trial. Obesity 18(1):36-44. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/oby.2009.430.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). 1997. Schools and Health: Our Nation’s Investment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/5153.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). 2004. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10883.

- Institute of Medicine. 2014. Implications of Health Literacy for Public Health: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18756.

- Kolbe, L. 2019. School health as both a strategy to improve both public health and education. Annual Review of Public Health 40:443-463. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043727.

- Luepker, R. V., C. L. Perry, S. M. McKinlay, P. R. Nader, G. S. Parcel, E. J. Stone, L. S. Webber, J. P. Elder, H. A. Feldman, C. C. Johnson, S. H. Kelder, M. Wu, P. Nader, J. Elder, T. McKenzie, K. Bachman, S. Broyles, E. Busch, S. Danna, T. Galati, K. Haye, C. Hayes, M. McGreevy, B. J. Williston, M. Zive, C. Perry, L. Lytle, R. Luepker, B. Davidann, P. Brothen, V. Dahlstrom, M. Dammen, S. Ehlinger, T. Greene, B. Hann, J. Heberle, T. Hoffl ander, C. Kelder, P. Kelliher, T. Kunz, B. Manning, D. McDuffi e, T. Morrow, M. Miller, J. Mrosala, G. Newman, M. Pusateri, M. Reinhardt, R. Sieving, J. Smisson, M. Smyth, P. Snyder, M. Staufacker, J. Traut, T. Wick, G. Parcel, S. Kelder, D. Montgomery, M. Nichaman, W. Taylor, K. Wambsgans Cook, E. Barrera, L. Berry, J. Carbonneau, K. Chemycz, P. Cribb, S. Evans, R. Gordon, J. Gwinn, S. Luton, B. Scaife, S. Sharkey, S. Snider, S. Spigner, K. Wilson, S. Woods, J. Wilmore, L. Webber, C. Johnson, T. Nicklas, V. Anthony, N. Baker, K. Barnwell, S. Belou, G. Berenson, S. Bonura, K. Bordelon, S. Cameron, A. Clesi, L. Crochet, A. Cunningham, D. Franklin, A. Haque, D. Harsha, J. Joy, S. M. Hunter, D. Kuras, P. Lambie, A. Layman, S. Little-Christian, S. Pedersen, J. Reeds-Epping, R. Rice, K. Romero, C. Pitcher-Smith, P. Strikmiller, M. White, S. McKinlay, S. Osganian, H. Feldman, H. Mitchell, S. Budman, P. Connell, M. Koehler, P. Mitchell, C. Kannler, G. Rennie, D. Sellers, M. Walsh, M. Yang, J. Dwyer, M. K. Ebzery, A. Garceau, L. Hewes, C. Hosmer, D. Raizman, L. Bausserman, E. Stone, M. Evans, J. Cutler, R. Lauer, T. Coates, W. Haskell, C. A. Johnson, R. Prineas, L. Van Horn, and J. Verter. 1996. Outcomes of a field trial to improve children’s dietary patterns and physical activity: The child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health. Journal of the American Medical Association 275(10):768-776. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1996.03530340032026

- Mann, M. J., and D. K. Lohrmann. 2019. Addressing challenges to the reliable, large-scale implementation of effective school health education. Health Promotion Practice 20(6):834-844. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919870196.

- Mayer-Davis, E. J., J. M. Lawrence, D. Dabelea, J. Divers, S. Isom, L. Dolan, G. Imperatore, B. Linder, S. Marcovina, D. J. Pettitt, C. Pihoker, and S. Saydah. 2017. Incidence trends of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002-2012. New England Journal of Medicine 376(15):1419-1429. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1610187.

- Means, R. K. 1975. A History of Health Education. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger.

- Melnyk, B. M., D. Jacobson, S. Kelly, M. Belyea, G. Shaibi, L. Small, J. O’Haver, and F. F. Marsiglia. 2013. Promoting healthy lifestyles in adolescents: A randomized control trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 45(4):407-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.013

- Minnesota Department of Health. Office of Statewide Health Improvement Initiatives. 2012. Statewide Health Improvement Partnership Evaluation Data. Reported by SHIP grantees using the REDCap system.

- Morse L. L. and D. D. Allensworth. 2015. Placing students at the center: The Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child model. Journal of School Health 85:785-794. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12313.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Health and Medicine Division. Roundtable on Health Literacy. Available at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/PublicHealth/HealthLiteracy.aspx#home (accessed May 3, 2020).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. Developing health literacy skills in youth and young adults. Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Pleasant, A., R. E. Rudd, C. O’Leary, M. K. Paasche-Orlow, M. P. Allen, W. Alvarado-Little, L. Myers, K. Parson, and S. Rosen. 2016. Considerations for a New Definition of Health Literacy. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201604a.

- Rasberry, C. N., G. F. Tiu, L. Kann, T. McManus, S. L. Michael, C. L. Merlo, S. M. Lee, M. K. Bohm, F. Annor, and K. A. Ethier. 2017. Health-related behaviors and academic achievement among high school students—United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66(35):921-927. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6635a1

- Rasberry, C. N., S. Slade, D. K. Lohrmann, and R. F. Valois. 2015. Lessons learned from the Whole Child and Coordinated School Health Approaches. Journal of School Health 85(11):759-765. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12307.

- Ratzan, S. C., and R. M. Parker. 2000. Introduction. In National Library of Medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy. NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000-1, edited by C. R. Selden, M. Zorn, S. C. Ratzan, and R. M. Parker. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Shattuck, L. 1850. Report of the Sanitary Commission of Massachusetts. Sanitary Commission; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Reprinted from Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1948, p. 178.

- Schillinger, D., J. Tran, and S. Fine. 2018. Do low income youth of color see “The Bigger Picture” when discussing Type 2 diabetes: A qualitative evaluation of a public health literacy campaign. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15(5):840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050840

- Sliepcevich, E. M. 1968. The school health education study: A foundation for community health education. Journal of School Health 38:45-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1968.tb04941.x

- US Department of Agriculture. Food and Nutrition Service. 2020a. National School Lunch program. Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/nslp (accessed May 18, 2020).

- US Department of Agriculture. Food and Nutrition Service. 2020b. National Breakfast Program. Starting the school day right with a healthy breakfast. Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/sbp/schoolbreakfast-program (accessed May 18, 2020).

- US Department of Education. 2020. The Federal Role in Education. Available at: https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/fed/role.html (accessed May 18, 2020).

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2010. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington, DC. Available at: https://health.gov/our-work/health-literacy/national-action-planimprove-health-literacy (accessed May 18, 2020).

- US Department of Health, Education, & Welfare. 1979. Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. DHEW (PHS) Publ. No. 79-55071. Washington, DC: Public Health Service.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2010. Healthy People 2020. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/DefaultPressRelease_1.pdf (accessed May 3, 2020).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2010. Healthy People 2020 Leading Health Indicator Topics: Social Determinants. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-healthindicators/2020-lhi-topics/Social-Determinants (accessed May 3, 2020).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2017. Secretary’s Advisory Committee Report on Approaches to Healthy People 2030. Healthy People 2030 Draft Framework. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about-healthy-people/development-healthy-people-2030/draft-framework (accessed May 15, 2020).

- Vernon, J. A., A. Trujillo, S. Rosenbaum, and B. De-Buono. 2007. Low health literacy: Implications for national policy. Available at: http://www.gwumc.edu/sphhs/ departments/healthpolicy/chsrp/downloads/LowHealthLiteracyReport10_4_07.pdf (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Videto, D. M. and J. A. Dake. 2019. Promoting health literacy through defining and measuring quality school health education. Health Promotion Practice 20(6):824-833. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919870194.

- Youth Speaks. 2018. The Bigger Picture Toolkit. Available at: http://youthspeaks.org/wp-content/uploads/The%20Bigger%20Picture%20Tool%20Kit.pdf (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Weise, E. and J. Wilson. 2019. “The eyes of future generations are on you,” Thunberg tells UN Climate Summit. USA TODAY. Available at: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2019/09/23/howdare-you-look-away-greta-thunberg-tells-un-climate-change-summit/2418058001 (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Winthrop, R. 2020. Covid-19 is a health crisis: So why is health education missing from school work? Available at: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2020-04-03-covid-19-is-a-health-crisis-sowhy-is-health-education-missing-from-schoolwork (accessed May 18, 2020).

- Zimmerman, M. A. 2013. Resiliency theory: A strengths-based approach to research and practice for adolescent health. Health Education & Behavior 40(4):381-383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113493782