Health Care Reform and Programs That Provide Opportunities to Promote Children’s Behavioral Health

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has dramatically changed the health care landscape, creating new opportunities to advance health promotion, prevention, and treatment for children, parents, and families (IOM and NRC, 2015). However, the programmatic and funding landscape for children’s behavioral health following implementation of the ACA largely remains siloed, as policy makers and industry stakeholders are focused broadly on the uninsured and reforming payment and delivery systems.

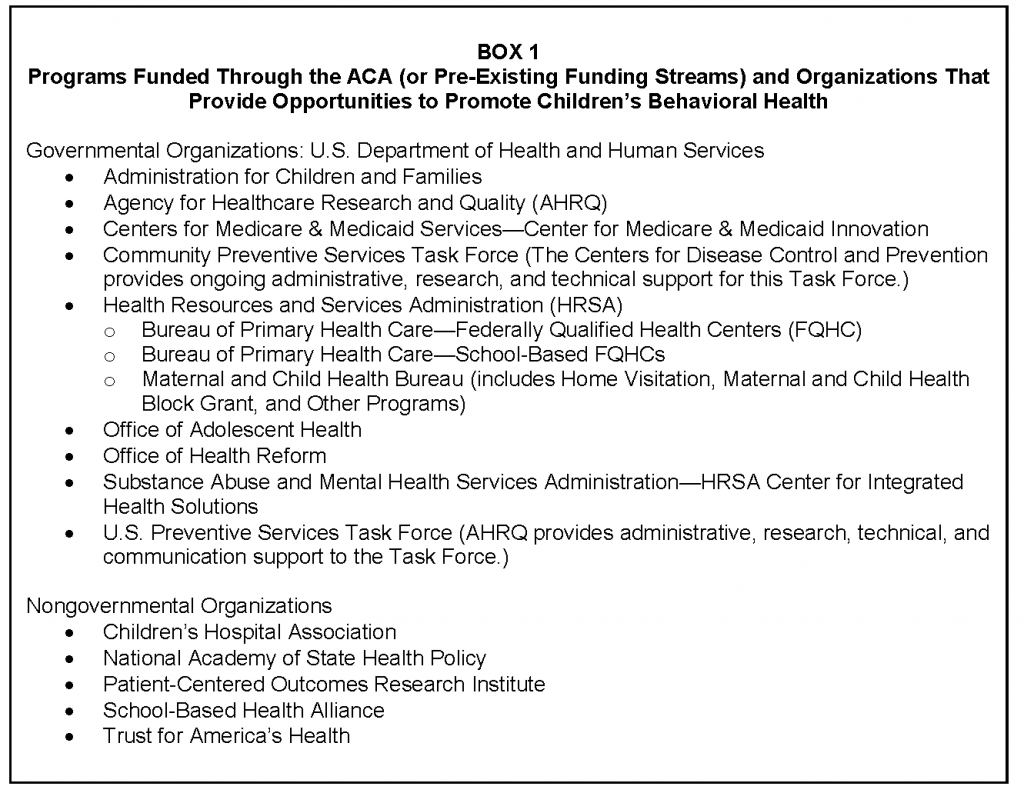

To see how the ACA has impacted children’s behavioral health, we explored several programs in both governmental and nongovernmental organizations from various vantage points of the health care system (see Box 1). We were able to identify areas where further programmatic or funding support was necessary to advance children’s cognitive and behavioral health, and from this scan, three key themes emerged:

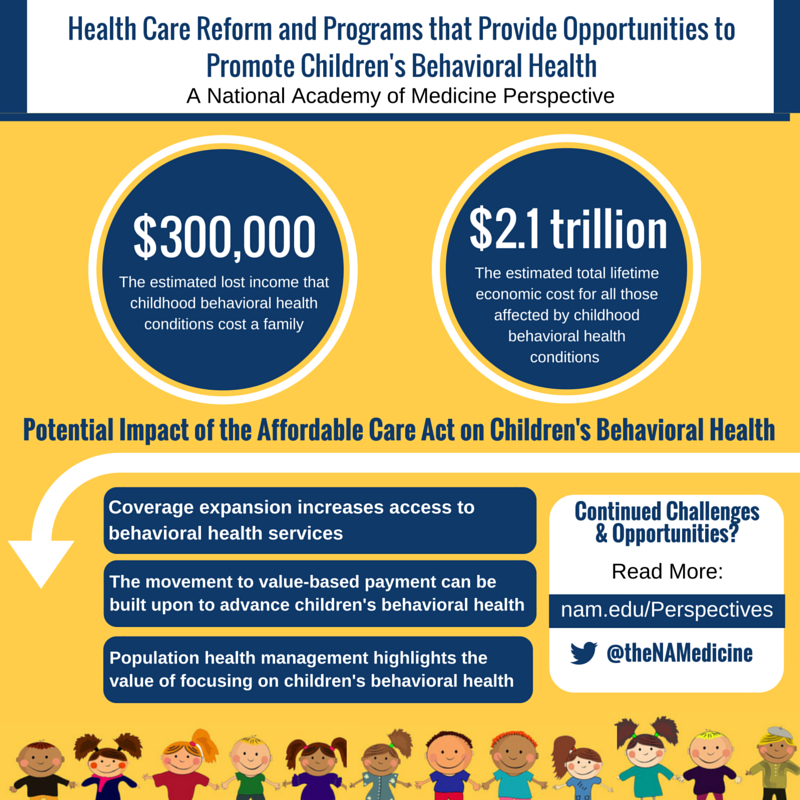

- The ACA’s Coverage Expansion: The coverage expansion potentially increases access to behavioral health care for adults and children, but the impact has been hard to assess.

- Movement to Value-Based Payment: Health reform catalyzed the movement to value-based payment, which can be built on to advance children’s behavioral health, including in the context of prevention.

- Population Health: Payers and providers are deploying population health strategies to promote prevention in support of population health and to manage high-cost, high-need subpopulations, making behavioral health a logical focus for these efforts.

The significant nature of broad trends and changes emerging from the ACA has created new ways to build on the coverage expansion, the movement to value, and the emphasis on population health with the goals of maximizing existing funding streams, connecting siloed programs, addressing longstanding workforce shortages to meaningfully improve access, and driving innovation in child- and family-focused care models and delivery systems.

This paper explores the impact of these three themes on children’s development, behavioral health, including in the context of prevention, and ends each section on the themes with key takeaways and insights. The paper then concludes with a synthesis and review of high-level opportunities for the children’s behavioral health community to engage with stakeholders to advance child and family health and development.

Introduction

Early Focus on Cognitive Development and Behavioral Health Important for Downstream Prevention and Benefits

A focus on behavioral health among policy makers, providers, and payers has been growing over the past several years due to a number of developments emerging from health reform. As is most often discussed, health reform’s coverage expansion has allowed millions of individuals to gain coverage for the first time. At the same time, health reform also accelerated major changes to the way providers are paid. Historically, most payment systems have been fee-for-service (FFS), in which providers are paid for the volume of services delivered; however, across payers and programs, payment models are shifting to focus on value—paying providers at least partially based on the cost and quality of care delivered. Health reform and the need to extract greater value for health care spending in the United States have resulted in three goals termed “the triple aim”—to improve health, to improve better care, and to reduce costs (Berwick et al., 2008). These broader changes are creating new opportunities to advance children’s behavioral health.

First, the passage of the ACA is increasing coverage for millions of Americans—mostly adults. The coverage expansion under the ACA increases access to insurance for adults, which research has shown makes it more likely that children will use health care, too (IOM, 2002). This is especially critical to addressing longstanding disparities in insurance coverage within families—with children in many families having insurance while parents remain without coverage. At the same time, the ACA also significantly expanded access to behavioral health services. The law created a new floor for coverage through the Essential Health Benefits (EHBs), which require coverage for mental health and substance use disorders (i.e., behavioral health).

Second, the ACA catalyzed the movement away from FFS payments to providers to value-based payments and models. These new payment models, such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs), bundled payments, and episodes of care, take both cost and quality into account. (Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) hold a group of providers jointly accountable for the cost and quality of care delivered to a defined population. Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs) are a model for organizing the delivery of primary care services so that care is comprehensive, patient-centered, coordinated, accessible, and of high quality. In this model, primary care practices are paid a per member per month fee to coordinate care for patients. Last, within bundled and episode-of-care payments, providers are paid a single price for all of the health care services for a condition or a specific treatment for an individual, such as following a heart attack, knee replacement, or an acute asthma episode. To succeed under these models many payers and providers are turning to population health management approaches that not only focus on delivering efficient and effective care, but also on promoting health and well-being to avoid downstream costs. As more adults and children gain coverage under the ACA—and payers and providers identify high-risk and/or high-need populations as part of the movement to value-based payment models—behavioral health will increasingly be part of a broader conversation in health care.

The high prevalence of behavioral health conditions in childhood is well established—and the impacts of these conditions on cognitive and affective development and physical health extend into adulthood. Beyond development, these issues impact quality of life and have long-term economic costs. The seminal 1999 Surgeon General’s report on children’s behavioral health estimated that approximately 10 percent of children and adolescents experience mental health conditions each year—and a startling 70 percent of those in need of treatment are unable to access care (HHS, 1999). A more recent examination of the literature indicated that approximately 12 to 22 percent of 3- to 17-year olds had behavioral health diagnoses (NRC and IOM, 2009). Nearly three-quarters of the cumulative prevalence of behavioral health problems, including substance abuse, anorexia nervosa, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and bulimia nervosa, have their onset before age 25 (Halfon, 2015; Kessler et al., 2007).

These conditions impact educational outcomes at a younger age—and eventually employment-related economic outcomes in adulthood. Research has found that of those 14 years of age and older with behavioral health issues, less than half graduate from high school and 70 percent are likely to be arrested within 3 years of leaving high school (Center on an Aging Society, 2003). Research has also established the near- and long-term economics costs of childhood behavioral health conditions. Annual costs are striking, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimating that mental health disorders among children result in an estimated annual cost of $247 billion due to their prevalence, early onset, and impact on not only children, but families and communities as well (Perou et al., 2013). Longterm economic costs to individuals and families, as well as to the broader economy, are significant—with estimates projecting that childhood behavioral health conditions such as depression can cost a family an estimated $300,000 in lost income and a total lifetime economic cost of $2.1 trillion for all of those affected (Smith and Smith, 2010).

The high prevalence of early onset behavioral health conditions in childhood and adolescence underscores the potential for early intervention to have downstream positive impacts into adulthood (HHS, 1999). While there has been movement and progress in understanding the onset of behavioral health conditions in childhood and adolescence and the benefits of early prevention, including individual-, family-, school- and community-based interventions, the prevalence and long-term economic costs of these conditions remains high. In that context, we undertook this area of further study to better understand the potential impact of the ACA on children’s behavioral health and to identify continued challenges and opportunities to implement prevention, early intervention, and treatment across all stages of development for children.

Key Themes

Coverage Expansion Increases Access to Behavioral Health Services, But Impact on Children Difficult to Assess

The passage and implementation of the ACA has arguably ushered in the most significant changes in health care since the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. One of the main goals of the ACA was to expand coverage to the nearly 50 million Americans who were uninsured prior to passage of the law through both Medicaid and through the purchase of private insurance on the new health insurance exchanges or marketplaces (CMS, 2014b). Since 2010, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) estimates that 20 million individuals have gained coverage (HHS, 2016). Coverage expansion and broader implementation efforts at HHS have focused on building the regulatory and technical infrastructure to identify and enroll individuals—mostly uninsured adults—into new coverage sources. Key takeaways on the impact and potential of the coverage expansion on children’s behavioral health include:

- The Medicaid expansion offers coverage for behavioral health care for low-income adults and children.

- The ACA’s EHBs increase access to behavioral health services for adult and pediatric populations.

- Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) are being embraced as critical settings for delivering preventive services and treating children with behavioral health needs and their families.

Medicaid Expansion Offers Coverage for Behavioral Health Care for Vulnerable Populations

The Medicaid expansion is increasing coverage for behavioral health services for low-income adults and children. The expansion has led to populations shifting from the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) to Medicaid in some states. This shift gives more children access to Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) services, which provide developmental and behavioral screening to children in Medicaid (CMS, 2015a). Starting in 2015, the ACA also extended Medicaid eligibility for children and young adults who aged out of the foster care system (and previously had Medicaid) until the age of 26. This provision was especially critical given that young adults are less often insured, and at the same time youth in foster care report both health conditions that limit their daily activities and receiving behavioral health counseling at higher rates than their peers (Lehmann et al., 2012). Youth in foster care make up only 3 percent of the Medicaid population but account for 29 percent of Medicaid expenditures for children’s behavioral health services, underscoring the importance and potential impact of early screening and intervention (CHCS, 2014). Last, the Medicaid expansion has largely impacted low-income adults, many of whom have behavioral health issues that in turn affect their children. As a result, there are likely to be long term parent, family, and community benefits from those individuals having access to medical and behavioral health services.

Essential Health Benefits Increases Access to Behavioral Health Services for Commercial Populations

The ACA mandates that all individual and small group market plans, as well as Medicaid programs, cover EHBs, which include mental health and substance abuse services. The EHB requirements built on the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA), which required group plans and commercial insurers that provided mental health or substance abuse services to provide them at parity with medical/surgical benefits. The law applied parity to substance abuse—a significant development given the heightened comorbidity with mental health and substance use disorders. More broadly, the law’s passage also sharpened the focus on the cost and quality impacts of providing behavioral health care across the health care system.

Taken together, these two federal policy developments have likely increased access to, and coverage of, behavioral health services. However, implementation of these policies has been complicated for a number of reasons, including a shortage of behavioral health providers (e.g., psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and others) especially for underserved and vulnerable populations, difficulties obtaining authorization from insurers for behavioral health services, and high costs of care (NAMI, 2015). For instance, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) cites that there is no practicing behavioral health provider in 55 percent of U.S. counties—and 77 percent of counties nationally report unmet behavioral health needs (SAMHSA, 2007; Thomas et al., 2009). The ACA authorized funding for workforce development programs, such as a $1.5 billion authorization for the National Health Service Corps that provides scholarships and loan forgiveness for primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants serving health professional shortage areas. However, a greater focus on behavioral health—and pediatrics in particular—may be necessary.

The coverage expansion, which includes increased coverage for evidence-based preventive screenings and services, has also created new opportunities to expand the sites where care can (and needs to be) accessed. For instance, there is widespread support for home visitation models that support at-risk families in their homes and communities. At the same time, not only has there been a growing awareness of the need to co-locate primary care and behavioral health services in ambulatory and community-based settings, but increased implementation of these models as well. In addition, the broad EHB categories do not necessarily result in coverage for specific services. The ACA also required commercial plans to cover preventive services that have an A or a B rating from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), as well as preventive care and screenings based on guidelines issued by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA’s) Bright Futures initiative at no out-of-pocket costs to enrollees. (The ACA provided a percent increase in the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) to states that cover USPSTF rated A or B services with no out-of-pocket costs for Medicaid beneficiaries.) However, the USPSTF has found insufficient evidence to issue an A or a B rating for many topics in pediatrics and behavioral health. Therefore, many prevention services in children’s behavioral health and development are subject to continued cost-sharing and out-of-pocket costs to families, resulting in a gap between coverage and access to care.

Community Health Centers and School-Based Health Centers Critical to Supporting Vulnerable Communities

The ACA provided $11 billion for FQHCs to support their ability to care for underserved and safety net populations, of which $1.5 billion was dedicated to capital improvements for increasing capacity to serve individuals gaining coverage under the ACA (HRSA, 2015a). However, FQHCs determine their health care program content locally and therefore the provision of behavioral health services and initiatives to promote children’s behavioral health and cognitive development are not system-wide.

SBHCs aim to increase access to primary care for student populations by delivering care through an integrated model that includes a range of services, including behavioral health. There are an estimated 2,000 SBHCs operating nationally and most offer care whenever schools are in session (HRSA, 2015c). However, SBHCs did not receive funding to expand provision of services in the ACA; yet, the law included $200 million for capital equipment (HRSA, 2015c). Given their potential to reach children and adolescents at risk for behavioral health issues, providing payment for services delivered in these settings could fill serious gaps in behavioral health promotion, screening, and access for underserved populations.

Takeaways: The ACA Coverage Expansion Creates Opportunities to Expand Access to Behavioral Health Screening and Support Services

While the ACA coverage expansion has been broadly focused on uninsured adults, there are a number of programmatic changes and funding streams that can be better leveraged to advance access to behavioral health promotion, screening, and services for children’s behavioral health. For consideration, several opportunities for the child and adolescent behavioral health communities include:

- Assess coverage expansion impact and gaps in children’s behavioral health. Examine the impact of the ACA coverage (and remaining gaps) on children’s behavioral health to help connect silos across federal agencies and programs, especially with programs that pre-date the ACA.

- Use existing research networks to build the evidence base. Leverage HRSA-led FQHC research networks to identify gaps in children’s behavioral health and areas where more data are needed on impacts and outcomes.

- Focus on outcomes and evidence generation from interventions in SBHCs and FQHCs. Connect researchers and stakeholders to generate evidence on the impacts and outcomes of screening, prevention, and treatment in FQHCs and SBHCs and other primary care settings and test models for effectively involving families and schools in interventions.

- Nominate topics for USPSTF and Bright Futures to consider. Bringing evidence-based preventive services to the attention of entities may assist in gaining favorable ratings and coverage for evidence-based screenings and preventive services.

- Support further developments in children’s behavioral health. Identify ways to close gaps between coverage and access, such as through innovative workforce programs.

Build on the Movement to Pay for Value to Advance Children’s Behavioral Health

In addition to expanding coverage to the uninsured, another primary goal of the ACA was to move from a predominantly FFS payment system for health care services to one that pays for value. The movement to value-based payments was largely driven by skyrocketing costs and low quality of health care services, including siloed and fragmented care. Quality problems plaguing the system have been well documented—starting with the seminal 2001 Institute of Medicine report Crossing the Quality Chasm. The report called for major reforms of the U.S. health care system to reduce problems with quality of care and gaps (IOM, 2001). Simultaneously, health care costs have been steadily climbing the past several decades and are projected to continue to do so without action. For instance, health care spending was 5 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 1960, but is now projected to reach 19.6 percent in 2024 (CMS, 2014b,c). This environment created the conditions for public and private payers to move away from an FFS payment system that was exacerbating these cost and quality trends. The goals of value-based payments align with a focus on children’s behavioral health because of the potential to reduce cost and improve outcomes for a high-need population; however, the following connections must be made between the behavioral health and broader medical community stakeholders and are discussed in more detail below:

- Build on existing payment and delivery reform efforts that have a children’s behavioral health component with federal entities driving the changes.

- Focus on Medicaid as a partner in advancing innovations in children’s behavioral health as payment and delivery reform accelerates across states.

- Create linkages to comparative effectiveness and other research efforts to advance best practices.

Build on Early Work of Federal Entities Driving Payment and Delivery Reform

The ACA established new entities, programs, and demonstrations to test payment and delivery system reforms, such as ACOs, health homes in Medicaid, and bundled payments or episodes of care. These payment and care management approaches present new opportunities for integrated approaches to care delivery and a potential for long-term cost savings by promoting prevention and early intervention. At the federal level, the ACA created the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), which is shaping and leading payment and delivery reform across payers. CMMI received $10 billion in mandatory appropriations in the ACA to test new payment and delivery models that can reduce federal health care costs for Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP beneficiaries while maintaining or improving quality.

CMMI does not have an explicit focus on children’s behavioral health despite the costs and long-term impacts of these conditions in childhood and across the lifespan, but there are early efforts that can be built on. For instance, CMMI distributed $1 billion in funding through the Health Care Innovation Awards (HCIA) to test promising care delivery models that reduce costs, with a focus on high-need populations (CMS, 2016). Approximately 25 percent of round 2 grants are examining care for children with medical complexities, such as behavioral health interventions and pediatric ACOs. In particular, the Coordinating All Resources Effectively (CARE) for Children with Medical Complexity project received approximately $23 million in funding to test systems of care for medically complex children in seven states (CMS, 2014a). CMMI also launched State Innovation Model (SIM) grants totaling nearly $1 billion to help states develop the financial and technical infrastructure to test multi-payer payment and delivery models that improve system performance and quality and decrease costs for beneficiaries of federal health programs and residents (CMS, 2015b). While many of the state SIM initiatives include a focus on behavioral health, they are not necessarily specific to children. SIM grants and other CMMI initiatives, present an opportunity to bring stakeholders to the table (payers, providers, government, etc.) and ensure that system transformation also addresses the needs of children.

Medicaid Payment and Delivery Reform Activity Accelerating

The movement to value is extending beyond just testing with activity well under way in the Medicaid program as well. Numerous state Medicaid programs are evaluating payment and delivery reforms; for instance, an estimated 18 states are testing ACOs and 22 are testing medical homes in some capacity (NASHP, 2015). To support these types of efforts, CMS funded the Medicaid Innovation Accelerator Program (IAP)—a $100 million investment to provide technical assistance and supports to states on issues such as Medicaid payment models, bundles for perinatal care and asthma (including children), and behavioral and physical health care integration.

Comparative Effectiveness Research Lacks Child Focus

The ACA also established the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). PCORI’s goal is “to improve the quality and relevance of evidence available to help patients, caregivers, clinicians, employers, insurers, and policy makers make informed health decisions.” (PCORI, 2014). PCORI aims to accomplish this by funding comparative effectiveness research (CER) to determine which services or treatments are most effective for patients in different circumstances (PCORI, 2014). The organization is funded through discretionary funds, transfers from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services trust funds, and a fee on commercial health plans (PCORI, 2014). Moving forward, PCORI is focused on a number of areas that align with children’s behavioral health, including integration with primary care, behavioral approaches to autism, diagnosis and management of adolescent bipolar disorder, interventions that impact chronic disease management, and the prevention and treatment of tobacco use.

Takeaways: Integrating Children’s Behavioral Health into Payment and Delivery Reforms Could Support Triple Aim

While the ACA aims to reduce costs, increase focus on quality, and improve outcomes, it will be important for connections to be made between behavioral health and broader medical community stakeholders. Possible actions include

- Call for CER and value-based payments to include focus on children’s behavioral health. CER entities, such as PCORI, could more explicitly focus on and fund research on the effectiveness of child and family behavioral health initiatives informed by pediatric research experts. In addition, while value-based payment efforts signal the extent to which the health care system is shifting, experts and stakeholders should call for this movement away from FFS to include a focus on physical/behavioral health integration and prevention for children, and two-generational or family-focused models of care.

- Examine CMMI initiatives to illustrate impact of children’s behavioral health on meeting metrics in value-based payments. Despite explicit lack of focus on behavioral health (especially in children), CMMI initiatives can yield important data and new models for improving quality and costs related to behavioral health conditions. Research findings from pilots and demonstrations should be assessed and disseminated to the broader community.

- Work with public and private payers to broaden the focus of value-based payments to include children and families. Partner with or initiate a dialogue with payers to provide expertise and a child- and family-centered focus to payment and delivery reforms under way at the federal and state levels, as well as with commercial payers. For instance, Medicaid IAP underscores interest in behavioral health integration, but explicit focus on children must be established. PCORI could be a partner in advancing CER on children’s behavioral health services and delivery systems as well.

- Build an integrated system of care for children in Medicaid. Medicaid programs in particular are focused on integrating clinical care and benefits for behavioral and physical health care, including prevention. These efforts should be extended to children and building a system of care for them.

Population Health Management Highlights Value of Focusing on Children’s Behavioral Health

Value-based payments align provider payments and other financial incentives with performance—usually on quality measures. There are a range of value-based payment models, but those that move toward global payments or hold providers accountable for managing a population of individuals, such as ACOs, also require a focus on population health. Providers and payers are engaging in population health management approaches to promote health and outcomes within a community not only through medical care, but also by focusing on prevention and health promotion by health care professionals, social services, community-based organizations, and public health agencies, among others. Recognition of the importance of population health to manage and promote the health and well-being of communities opens the door to broadly implement child- and family-focused prevention and treatment.

The most prominent example of a two-generation intervention aimed at prevention and the promotion of child health and development is the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program authorized in the ACA, which is administered by HRSA in collaboration with the Administration for Children and Families (ACF). The program supports pregnant women and their families, as well as at-risk parents with children from infancy to kindergarten, connecting them to resources and helping them develop skills that foster physical, social, and emotional health in their children (HRSA, 2015b). Congress appropriated $1.5 billion for the program and has extended it through fiscal year 2017 (HRSA, 2015b). Since 2012, the program has made more than 1.4 million home visits across all 50 states (HRSA, 2015b). The program is a model not only for its effectiveness, but also because of the collaborations it has fostered within HHS and its integration into new payment and delivery models. For instance, home visitation programs are working with FQHCs and some are also co-located with medical homes coordinated by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). The impact and breadth of the model is potentially wide-ranging, as it affects healthy development beyond childhood as well as economic prosperity and is an example of a “next-generation” intervention aimed at at-risk children and families that promotes long-term population health outcomes.

There are also other interagency efforts under way across HHS that support population health goals. In particular, ACF is part of a number of interagency collaborations to support early childhood development. Efforts include integrating home visiting programs into broader systems of early childhood care and bringing a health care perspective to early childhood programs including home visiting, Head Start, and the U.S. Department of Education’s Race to the Top Fund. ACF is also working with other agencies, states, and grantees to identify new prevention opportunities created by the ACA that can support the health and well-being of children and families, such as depression screening in mothers. Last, ACF’s Birth to Five: Watch Me Thrive! initiative is a coordinated federal effort aimed at promoting healthy child development through universal developmental and behavioral screenings and support for families and providers (ACF, 2016). These types of interagency collaborations and efforts underscore that the ACA has created new opportunities to promote child and family well-being and health and to support broader population health goals.

Takeaways: Alignment of Population Health and Children’s Behavioral Health Goals Must Be Highlighted

New payment and delivery models—especially those that are outcomes- and risk-based or provide global payments—align payment incentives with population health goals. Given the potential for early intervention for at-risk children and families to produce positive long-term outcomes, a focus among payers and providers on children’s behavioral health and family-based interventions for those at risk could have positive impacts across health care and other domains (Robertson et al., 2016). Specific areas where progress could be made to align population health with children’s behavioral health include

- Craft payment policies that support population health goals. While SBHCs have expanded since the ACA, the system is still largely FFS; as such, SBHCs rely on grant dollars to provide preventive, parent engagement, and teacher services. An analysis of, and recommendations for, how payment policies for FQHCs and SBHCs, among other care settings, can promote population health could support broader system goals.

- Build a long-term case to support two-generational models of care. Articulate the important link between parent behavioral health and health outcomes for children as a reason why payers should support two-generational models of care and interventions as part of population health management. While CMS and CMMI acknowledge there is a federal role for supporting population health, current research and limitations in projecting economic and other benefits in the long term may be limiting how the agency can support population health interventions (Kassler et al., 2015). However, a growing body of research demonstrates the long-term positive benefits versus costs of early childhood prevention, which should be brought to the attention of policy makers (and further built on) to support greater testing and support for two-generational models of care (NIDA, 2016).

Conclusion

Integrating Children’s Behavioral Health into System-Level Efforts Is Important to Improving Value and Drive Population Health

The ACA has created new opportunities for advancing the health and well-being of many populations, including the developmental and behavioral health of children. The ACA does this by expanding coverage—mental health and substance abuse services in particular—to the uninsured and through value-based payment reforms that are creating new incentives for population health management strategies that include behavioral health promotion and disorder prevention. While these broader trends and impacts will hopefully improve the health and wellbeing of adults in at-risk or low-income families and communities in general, there is little focus on children’s behavioral health and prevention in the context of the ACA. There also appears to be limited coordination across federal agencies post-ACA to advance children’s behavioral health within this larger context.

The broader policy developments and trends, however, create a positive environment for testing and scaling prevention and community-based care approaches for at-risk children and families, as well as screening and treatment services to address behavioral health issues early in childhood. Potential opportunities for child development and behavioral health experts and stakeholders to advance the goals of improving and promoting child, parent, and family health and well-being in the context of broader health care system changes can be grouped by the main trends reviewed in this paper (see Table 1).

The ACA aimed to (1) expand coverage to the uninsured; (2) ensure coverage includes a basic set of benefits, including behavioral health promotion and care; and (3) catalyze changes in the payment and delivery of health services so that patients receive better care and experience better health at lower costs. Many of the historical siloes in health care are being connected in this new environment, but the landscape for children’s behavioral health, including prevention, remains largely siloed from these developments. However, the rapidly shifting environment in health care is creating promising opportunities to align the goals of advancing children’s behavioral health and development with overall health system transformation.

Note: Note that the use of the term “behavioral health” throughout this paper is intended to encompass mental health, substance abuse, as well as cognitive and affective development and health.

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- ACF (Administration on Children and Families). 2016. Birth to 5: Watch me thrive! Available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ecd/child-health-development/watch-me-thrive (accessed March 14, 2016).

- Berwick. D., T. Nolan, and T. Whittington. 2008. The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Affairs 27(3):759-769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Center on an Aging Society. 2003. Child and adolescent mental health services: Whose responsibility is it to ensure care? Washington, DC: Health Policy Institute, Georgetown University. Available at: https://hpi.georgetown.edu/agingsociety/pubhtml/mentalhealth/mentalhealth.html (accessed January 19, 2016).

- CHCS (Center for Health Care Strategies). 2014. Medicaid behavioral health care use among children in foster care. Available at: http://www.chcs.org/media/Medicaid-BH-Care-Use-for-Childrenin-Foster-Care_Fact-Sheet.pdf (accessed March 16, 2016).

- CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2014a. Health Care Innovation Awards Round Two project profiles. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/HCIATwoPrjProCombined.pdf (accessed January 19,

2016). - CMS. 2014b. National health expenditure projections 2012-2022. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-andreports/nationalhealthexpenddata/downloads/proj2012.pdf (accessed July 20, 2016).

- CMS. 2014c. Table 1. National health expenditures; aggregate and per capita amounts, annual percent change and percent distribution: Selected calendar years 1960-2014. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-andReports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html (accessed July 20, 2016).

- CMS. 2015a. Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/ByTopics/Benefits/Early-and-Periodic-Screening-Diagnostic-and-Treatment.html (accessed January 19, 2016).

- CMS. 2015b. State Innovation Models initiative: General information. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/State-Innovations (accessed January 19, 2016).

- CMS. 2016. Health care innovation awards. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Health-CareInnovation-Awards (accessed January 19, 2016).

- Halfon, N. 2015. Optimizing the behavioral health of all children: Implications for policy and systems change. Keynote at Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Workshop on Opportunities to Promote Children’s Behavioral Health: Health Care Reform and Beyond, Washington, DC.

- HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 1999. Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Available at: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/access/NNBBHS.pdf (accessed January 19, 2016).

- HHS. 2016. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-insurance-coverage-and-affordable-care-act2010-2016 (accessed June 12, 2016).

- HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). 2015a. Bureau of Primary Health Care fact sheet. Available at: http://bphc.hrsa.gov/about/healthcenterfactsheet.pdf (accessed January 15, 2016).

- HRSA. 2015b. Maternal, infant, and early childhood home visiting. Available at: http://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs/homevisiting/ (accessed January 15, 2016).

- HRSA. 2015c. School-Based Health Centers. Available at: http://www.hrsa.gov/ourstories/schoolhealthcenters (accessed January 15, 2016).

- Institute of Medicine. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10027

-

Institute of Medicine. 2002. Health Insurance is a Family Matter. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10503

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2015. Opportunities to Promote Children’s Behavioral Health: Health Care Reform and Beyond: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21795

- Kassler, W., N. Tomoyasu, and P. Conway. 2015. Beyond a traditional payer—CMS’ role in improving population health. The New England Journal of Medicine 372(2):109-111. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1406838

- Kessler, R. C., G. P. Amminger, S. Aguilar-Gaxiola, J. Alonso, S. Lee, and T. B. Ustun. 2007. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 20(4):359-364. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c

- Lehmann, B., J. Guyer, and K. Lewandowski. 2012. Child welfare and the Affordable Care Act: Key provisions for foster care children and youth. Center for Children and Families, Georgetown University. Available at: http://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/ChildWelfare-and-the-ACA.pdf (accessed January 19, 2016).

- NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness). 2015. A long road ahead: Achieving true parity in mental health and substance use care. Available at: https://www.nami.org/About-NAMI/PublicationsReports/Public-Policy-Reports/A-Long-Road-Ahead/2015-ALongRoadAhead.pdf (accessed January 13, 2016).

- NASHP (National Academy for State Health Policy). 2015. Maps. Available at: http://www.nashp.org/category/map-2 (accessed January 13, 2016).

- NIDA (National Institute on Drug Abuse). 2016. Principles of substance abuse prevention for early childhood. Available at: https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-substance-abuseprevention-early-childhood/appendix-1-theory-to-outcomes-designing-evidence-basedinterventions#benefit-cost-examples-for-early-childhood-programs (accessed March 24, 2016).

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. 2009. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12480

- PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute). 2014. About us. Available at: http://www.pcori.org/about-us (accessed January 13, 2016).

- Perou, R., R. H. Bitsko, S. J. Blumberg, P. Pastor, R. M. Ghandour, J. C. Gfroerer, S. L. Hedden, A. E. Crosby, S. N. Visser, L. A. Schieve, S. E. Parks, J. E. Hall, D. Brody, C. M. Simile, W. W. Thompson, J. Baio, S. Avenevoli, M. D. Kogan, and L. N. Huang. 2013. Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2005-2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62(2):1-35. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6202a1.htm (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Robertson, E. B., B. E. Sims, and E. E. Reider. 2016. Drug abuse prevention through early childhood intervention. In The handbook of drugs and society, edited by H. H. Brownstein. West Sussex, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Pp. 525-554.

- SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2007. An action plan for behavioral health workforce development. Available at: http://annapoliscoalition.org/wpcontent/uploads/2013/11/action-plan-full-report.pdf (accessed March 24, 2016).

- Smith, J., and G. Smith. 2010. Long-term economic costs of psychological problems during childhood. Social Science and Medicine 71(1):110-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.046

- Thomas, K. C., A. R. Ellis, T. R. Konard, C. E. Holzer, and J. P. Morrissey. 2009. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatric Services 60(10):1323-1328. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1323