Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention: A New Framework

High obesity prevalence persists as a major issue for societies globally (IOM, 2012; WHO, 2013). Chronic overweight and obesity have high health, social, and economic costs (Hammond and Levine, 2010), and the benefits of achieving and maintaining healthy weight for overall health and well-being are well established (Horton, 2009; IOM, 2012; Wing et al., 2011; Zomer et al., 2016). Obesity in children and adolescents is of particular concern because it may compromise physical and psychosocial development and set the stage for early onset of adverse health effects that accumulate over a lifetime (IOM, 2005). Relevant to the topic of this discussion paper, obesity is also a health equity issue. Social disadvantage tends to intensify the exposure to obesity-promoting influences (Braveman, 2009; May et al., 2013). The challenge of preventing and controlling obesity includes the need to assure that socially disadvantaged populations benefit from relevant public health interventions (IOM, 2013).

Population-wide obesity and its health consequences are linked to eating and physical activity patterns that have become ways of life in modern societies (IOM, 2012; Kumanyika et al., 2008; WHO, 2000). This is a global problem, but one for which solutions must be tailored to national and subnational contexts (WHO, 2000). Human physiologic systems for regulation of food intake are well developed for responding to hunger but poorly developed for curbing overeating, and they evolved when routine physical activity levels were much higher than they are now. Thus, it is often said that from an evolutionary perspective widespread obesity reflects a natural response to an unnatural environment. On the energy intake side, this unnatural environment is characterized by ubiquitous, heavily advertised, and highly palatable high-calorie foods and beverages and large portions of restaurant meals; these all promote caloric overconsumption. On the energy output side, the unnatural environment is evident in residential areas where cars are a common form of transportation or where mobility depends on using a car, in sedentary work environments that limit physical activity, and where sedentary entertainment is readily available, affordable, and heavily promoted.

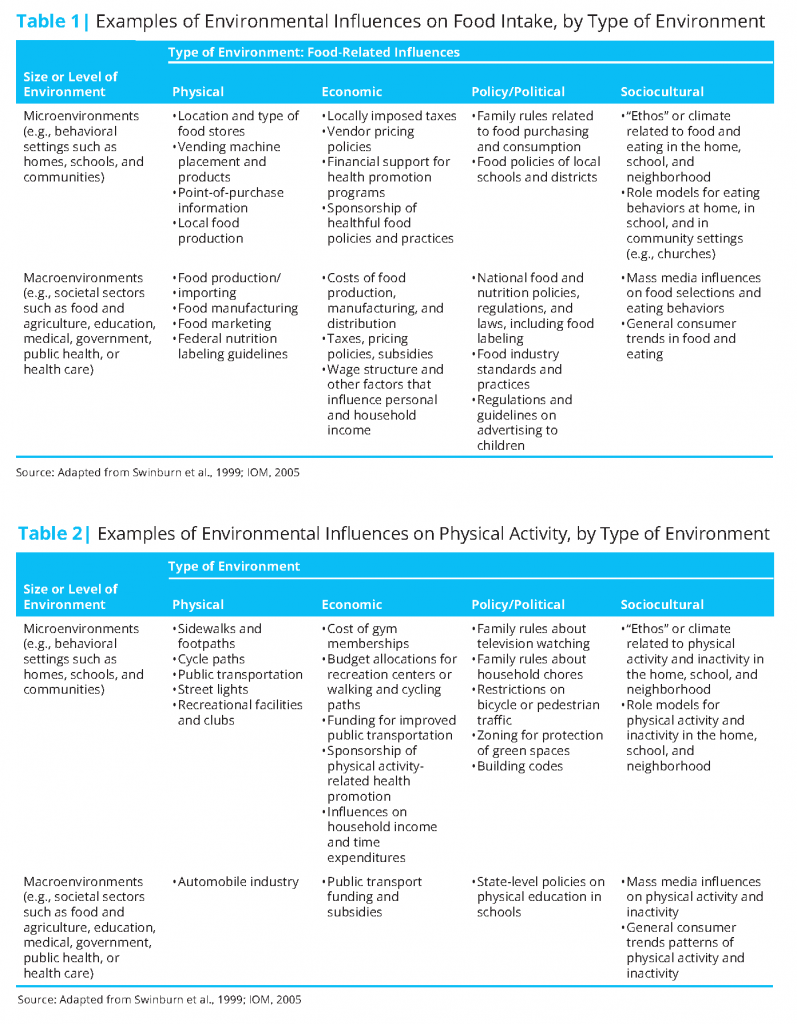

Our communities are laden with obesity-promoting influences that often overwhelm efforts of individuals to control their weight. The current public health priority for transforming environments to be more supportive of healthy eating and physical activity recognizes this reality. Tables 1 and 2 list various types of obesity-promoting influences in daily living environments (microenvironments) as well as factors farther upstream (macro environments). These tables are adapted from Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance (IOM, 2005). This report was among the earliest U.S. efforts to shift the obesity intervention paradigm toward public health approaches. The tables depict the spectrum of factors and environments that influence eating and physical activity. The focus of this perspective is on those factors that are amenable to modification by altering existing public or private policies or by establishing new ones.

A General Framework for Obesity Prevention in the United States

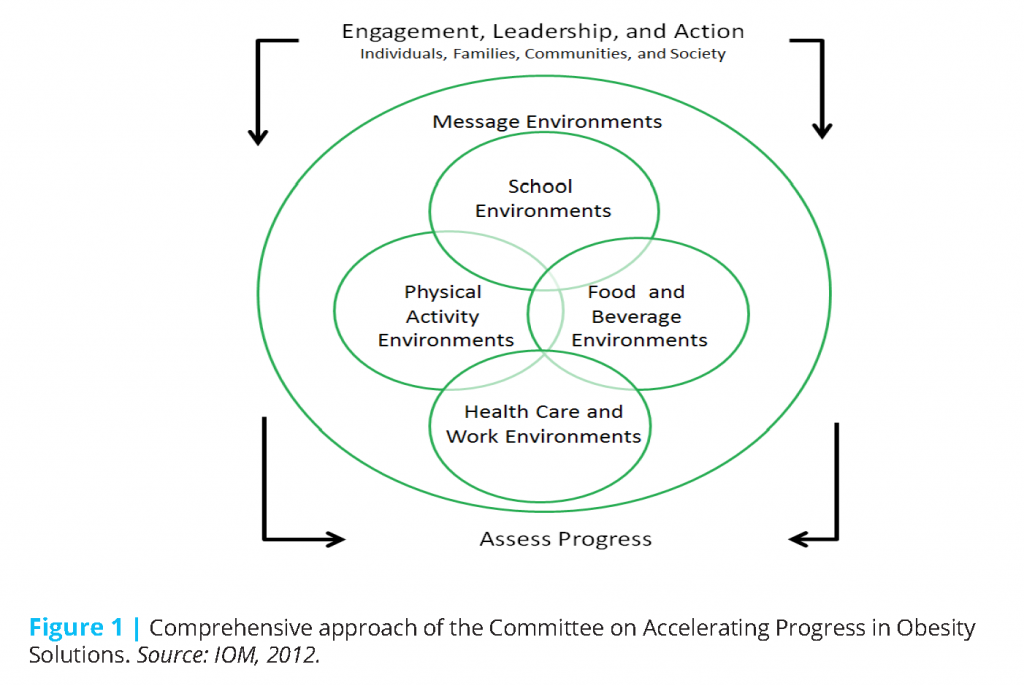

The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention (APOP) (2) (IOM, 2012) developed strategies and action plans that have become a reference point for current U.S. obesity prevention efforts with both children and adults. The APOP study committee reviewed hundreds of recommendations for preventing obesity and arrived at five recommendations, 20 accompanying strategies for implementing these recommendations, and a number of potential action steps for each strategy (IOM, 2012). Taken together, the recommendations, strategies, and action steps form a comprehensive strategy to foster obesity prevention in key environments or “settings.” The approach was grounded in a systems perspective to encourage actions within and across settings that were complementary and could be mutually reinforcing (Figure 1).

Characteristics of the settings in the APOP framework define the overall context for choice options, motivations, and actions regarding eating and physical activity for individuals and communities. Potential targets for interventions in these settings include the types of foods available in neighborhoods and settings such as schools, child care facilities, or worksites; food prices; advertising and promotion of unhealthy foods and beverages; public transportation; traffic patterns, air quality, and other aspects of neighborhood safety and quality; and access to parks and recreational facilities. These factors are difficult to change.

The APOP framework also highlights the roles of engagement and leadership in effecting changes in these environments. Environments related to healthy eating and physical activity are not only a part of the fabric of everyday life, they also reflect processes that are useful to communities in other ways and are, therefore, protected by a combination of public policies, commercial interests, and public preferences. For example, school policies may limit time for physical education in favor of more time for academics. Community design practices that are efficient for automobile transportation and suburban living may take priority over configurations that make it possible for children to walk to nearby schools.

Health Equity Considerations

We continue to observe substantially higher obesity prevalence in U.S. racial/ethnic minorities compared to white populations. For example, in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data based on measured

weights and heights, 48 percent of non-Hispanic black adults and 43 percent of Hispanic adults had obesity, compared to 35 percent of non-Hispanic whites (Ogden et al., 2015). The figures for obesity prevalence in 2- to 19-year-old youth were 20 percent and 22 percent for non-Hispanic black and Hispanic youth, respectively, compared to 15 percent in non-Hispanic white youth (Ogden et al., 2015). The self-reported data from the National Health Interview Survey indicate higher obesity prevalence in American Indians/Alaska Native adults (44 percent) and Native Hawaiians or other Pacific Islanders (35 percent), compared to non-Hispanic whites (29 percent) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016). Higher obesity prevalence in association with lower socioeconomic status (SES) is also a frequent finding (May et al., 2013; Ogden et al., 2010a,b), although in the United States this finding is less consistent within racial/ethnic minority populations than in whites. Also, trends in obesity prevalence are sometimes less favorable for racial/ethnic minority or low SES population subgroups than those observed for non-Hispanic white or higher SES groups; in such cases, disparities are actually widening (CDC, 2015; Frederick et al., 2014; Robbins et al., 2015).

These differences in obesity prevalence and trends are not chance occurrences. Although obesity-promoting forces are embedded in the social fabric of daily living and affect the whole population, the finding that above-average obesity prevalence is often associated with low SES or racial/ethnic minority status is not uncommon in high-income countries like the United States (Kumanyika et al., 2012; Loring and Robertson, 2014). Population groups whose opportunities and social agency have been systematically and unfairly curtailed tend to be more exposed to obesity-promoting environmental influences and less able to avoid the associated adverse effects on eating and physical activity. This makes obesity a health equity issue rather than simply one of health differences between population groups that are otherwise comparable in social position and opportunities.

The APOP report (IOM, 2012, p. 26) acknowledged that challenges in social, political, and historical contexts influence the feasibility and relevance of interventions designed to improve options for healthy eating and active living, stating in the opening chapter of the report:

Not all individuals, families, and communities are similarly situated with respect to environments that influence food and physical activity…In many parts of the United States, racial/ethnic minority and low-income individuals and families live, learn, work, and play in neighborhoods that lack sufficient health protective resources, such as parks and open space, grocery stores, walkable streets, and high-quality schools (Adler et al., 2007; Iton et al., 2008). The persistence of concentrated health disparities in many American communities is strongly influenced by the relative paucity of community-based health improvement strategies focused on creating robust local participatory decision-making processes.

Although the APOP committee did not find evidence to support recommendations for specific population subgroups, it advanced a vision in which solutions would be sensitive to contexts and oriented toward achieving equity (IOM, 2012). Unless addressed through specially designed interventions, the disproportionately high exposure to a variety of obesity-promoting factors in socially disadvantaged communities may limit the effectiveness of interventions that benefit the population at large. Closing gaps will actually require interventions that work better in these populations than they do in white or more advantaged populations. Equivalent or better impacts in advantaged compared to disadvantaged populations mean that gaps in obesity prevalence will widen rather than become smaller (Chung et al., 2016; IOM, 2012).

An Equity-Oriented Obesity Prevention Framework

Thus, as useful as the APOP framework and recommendations have been and will continue to be, they do not provide specific guidance on how to develop strategies that will lead to equity of impact. Although the idea that populations with a more challenging context for change would require specially tailored approaches may seem like common sense, the fact that specially designed programs require additional resources may cause policymakers to favor one-size-fits-all strategies. The need for a framework that enables an explicit focus on equity is supported by the principle of “proportionate universalism,” or having the same goals for all in terms of outcomes, but applying interventions selectively according to circumstances and in proportion to need to achieve these outcomes (Carey et al., 2015; Loring and Robertson, 2014).

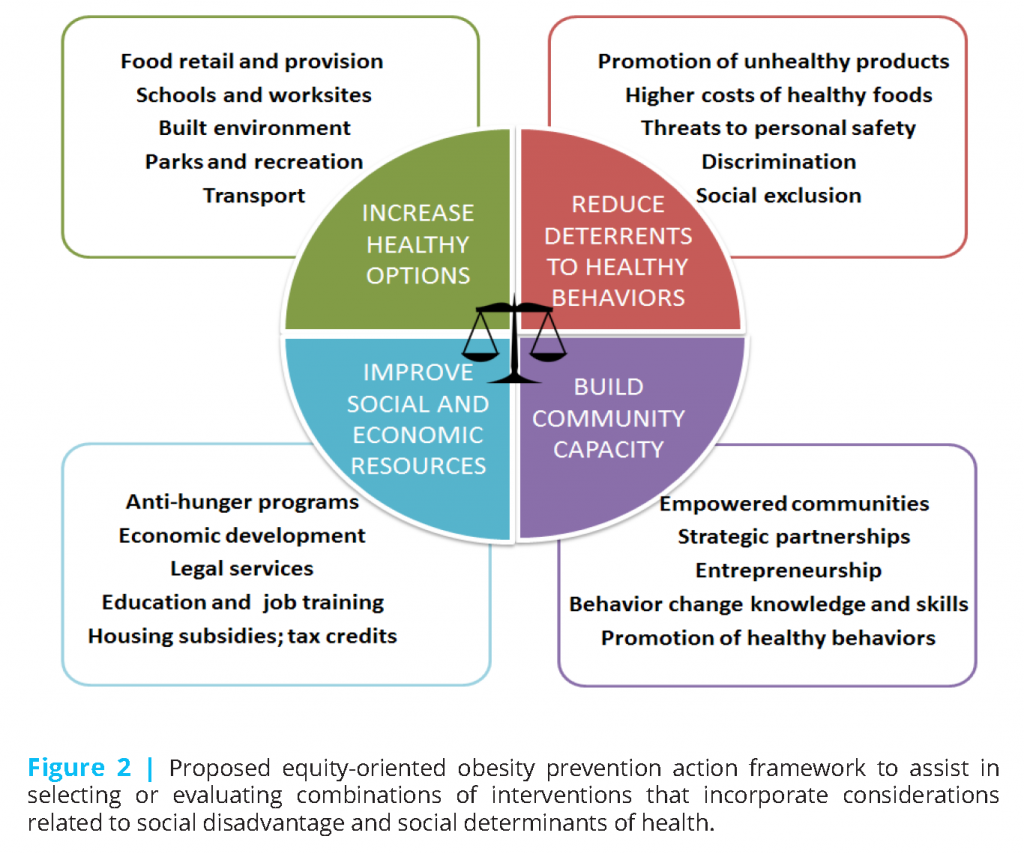

The process of getting to equity in achieving healthy weight cannot move forward until certain societal determinants of obesity are altered. The fact that this is a long-term proposition can discourage action because of uncertainty about how to proceed. A strategy that includes efforts with both short- and long-term payoffs is essential, but now is the time to begin in earnest. We can now identify the key environments to be targeted for change in obesity prevention, as well as goals, strategies, and actions relevant to the population as a whole. We can also recognize the various types or sources of inequities in social and environmental context factors that pose challenges for effective interventions (IOM, 2012, 2014). In addition, there is increasing emphasis not only in the field of obesity prevention but also in public health policy and practice more broadly on comprehensive community health improvement strategies. These strategies leverage the missions and resources of many societal sectors with an explicit emphasis on addressing social determinants of health (APHA, n.d.; Kania and Kramer, 2011; Koh et al., 2011; RWJF, 2015). Thus, the concepts needed to move forward with an equity-oriented obesity prevention strategy are in place. A proposed framework for an operational approach to such as strategy is shown in Figure 2.

The framework has four quadrants representing “process” categories that complement the settings oriented perspective in the APOP framework. These process variables emerge when one asks: “What is it we are trying to accomplish in these settings?” Asking this question leads to a people-oriented perspective that supports a classification of interventions according to how they affect people in communities or population subgroups. Theoretically, the elements of this framework are applicable to any population or community. However, as shown here, they are designed to highlight pathways whereby inequities can be mitigated. Each of the four categories is explained below. The items within each category are not intended to be exhaustive or highly specific; rather, they are selected as examples that illustrate potential intervention targets or approaches.

Increase Healthy Options

This category focuses on interventions that are core to many obesity prevention recommendations for environmental and policy change generally (e.g., as exemplified in the APOP recommendations (3)) and are particularly important from an equity perspective. Examples include improving locations and in-store marketing practices of supermarkets; implementing standards for food provision in schools and child care settings, worksites, and public places; improving availability and quality of parks and recreational facilities; and improving neighborhood walkability, transit systems, or other neighborhood conditions.

Reduce Deterrents to Healthy Behaviors

The focus in this category is on improving the balance of health-promoting and health-damaging exposures by decreasing messages promoting unhealthy foods or behaviors, making unhealthy options less affordable, and otherwise reducing physical and social conditions that discourage healthy behaviors. Measures to decrease targeted marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children would have a disproportionate benefit for children in ethnic minority populations, who are exposed disproportionately to targeted marketing for such products. Taxing or reducing access to sugary beverages would fit within this category as would policies and programs that remove blight, decrease crime, or prohibit unfair (whether intended or inadvertent) exclusions of people from pathways to health because of their demographic characteristics.

Improve Social and Economic Resources

This category goes beyond what is typically included in frameworks for promoting healthy eating and physical activity but is core to efforts to address inequities. It calls for specific attention to solutions that, although not directly focused on health, have well-documented effects on health, such as mitigating poverty and improving employment options, as well as improving social and housing conditions. Antihunger programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), or child nutrition programs (including the Child and Adult Care Food Program) fit here because they increase food purchasing power or provide economic relief through direct food provision. Legal services could be relevant in several ways for removing discriminatory policies and advocating for policies or provisions to improve equity within policies. Examples include changing land use or zoning policies, enforcing equal opportunity and housing policies, or assisting with interactions with the criminal justice system.

Build Community Capacity

This category is of particular importance for an equity focus because it emphasizes the importance of community engagement, meaning directly involving community members in a process of reflecting on, selecting or designing, implementing, and evaluating outcomes of interventions with a health or resources focus. Community engagement employs processes that support the individual and collective ability of people in a given intervention setting to act effectively on their own behalf within their living and working environments, and in ways they perceive as consistent with their interests, identities, and aspirations (Bandura, 2006; IOM, 2012). Collective efficacy (community members’ confidence in the ability to succeed in taking actions to improve their circumstances) can also be addressed in interventions (Kumanyika et al., 2012). Strategic partnerships may involve different types of organizations within a community: across public sectors such as housing, education, transportation, and economic development; among civic and health organizations; and throughout academic and private sectors as well. As noted above, such partnerships are now considered fundamental to community health improvement in general. Entrepreneurship is included to suggest a role for approaches that build capacity, such as business development in low-resource communities, in addition to approaches that depend on public funding or philanthropy for revenue streams. As previously shown in Figure 2, increasing capacity also includes the concept of increasing awareness of and receptivity to improved options for healthy eating and physical activity and other aspects of health and well-being (mobilizing demand) through increased health knowledge, food and nutrition literacy, exposure to campaigns that market healthy foods and active living options, and direct experiences with healthy products and activities.

The Potential for Synergy

The scales of justice in the center of the figure signify the theoretical likelihood that an impact on equity in the ability to prevent obesity is most likely when complementary interventions from all four categories are undertaken in concert in a way that can be synergistic, or mutually reinforcing. This four-pronged approach is consistent with the general principle that coordinated multifactorial solutions are needed to address complex public health problems such as obesity. It also underscores the need for intervention packages that incorporate direct actions on social determinants of health in order to generate effective, sustainable, and equitable solutions.

Achieving Equity of Impact

The application of this Equity-oriented Obesity Prevention Action Framework can be informed by an emerging body of evidence that identifies key aspects of approaches likely to foster equitable obesity prevention solutions (Backholer et al., 2014; Beauchamp et al., 2014; Boelsen-Robinson et al., 2015; CDC, 2014; Taylor et al., 2015). One aspect is intentionality, meaning the deliberate selection or design of health interventions with an awareness of what resources and capacity are required for them to be effective in a given population group and taking steps to ensure that these resources are provided. This is a type of proportionate universalism that is broader than only attending to the aspects of the intervention that are directly health-related or controlled by the health sector. This approach ultimately requires creating multidisciplinary teams and reaching across sectors to generate whole community approaches that are built on a solid foundation of community engagement.

Although this equity-oriented framework has yet to be applied in practice, one can envision various approaches to its use with a specific demographic group or within a geographic area or virtual community of interest to decide how to proceed.

A key step is convening relevant experts and stakeholder groups with knowledge of approaches in each category in the framework (type of solution), engage them to think through a coordinated strategy and identify metrics for assessing success. This approach would facilitate an environmental scan for potential policy instruments or programmatic tools that are available in each of the four categories, and particularly those in the resources, capacity, and deterrents categories that usually are considered “out of sector” from the perspective of public health or health care professionals. Such assessments would ideally be done with a specific health goal in mind even when the health goals are identified secondary to other critical community priorities for change. Assessments should also be done with an eye to identifying existing community assets, not just problems or deficits, and potential ways

to build on and leverage these assets. In the process, each set of stakeholders would learn more about the different action strategies and about each other, and collectively identify relevant precedents, outcomes, and tools. Once potential interventions or approaches have been identified, the selection process would aim for synergy among a set of strategies selected from the different categories, some with longer-term goals and some with more immediate payoffs expected. Criteria for selection in addition to the potential relevance and impact of separate interventions on obesity prevention would include the potential for effects of different types of policies or programs to be mutually enhancing.

Another way to approach using the framework would be to start with proposals for specific obesity prevention strategies that have public support and political traction and analyze them to identify and consider what other interventions or resources or capacity would potentially improve their effectiveness. The subsequent process might proceed similarly to the aforementioned approach of reaching out to other sectors, forming or joining a coalition, and moving forward with an action plan geared to complementarity and co-benefits among the participating partners.

Case Examples

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is an urban area with a population of about 1.5 million people, of whom about sixty percent are black or Hispanic, and where the percent of people living in poverty (26 percent) or deep poverty—less than half of the poverty line—(12 percent) are highest among the 10 most populous U.S. cities (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016; Lubrano, 2014). The Philadelphia experience with childhood obesity prevention is an example of how interventions involving multiple categories in the equity-oriented framework can be effectively combined and coordinated. Progress in reducing rates of child obesity in Philadelphia includes improvements in high-risk demographic groups (Robbins et al., 2012, 2015). A case study analysis of the factors contributing to this success documented numerous and varied multilevel approaches for increasing healthy eating and physical activity options, implemented over several years and involving various actors across multiple sectors (Dawkins-Lyn and Greenberg, 2015). The most recent, widely publicized success was the passage of a sweetened-beverage tax (a deterrent to consumption of these products) for which planned uses of revenues included funding for universal prekindergarten. This has major implications for achieving educational equity (Nadolny, 2016; Sanger-Katz, 2016).

The political leverage achieved by linking the tax to a resource-related rationale rather than a primarily health rationale was contrasted with the prior, unsuccessful attempt to pass such a tax when framed in public health terms. However, both the prior effort and the ultimately successful more recent effort to pass the tax were useful in raising community awareness and building capacity, and were probably aided by a prior communications campaign to “de-market” consumption of sweetened beverages (Dawkins-Lyn and Greenberg, 2015). Going forward, adding or intensifying other complementary strategies might further enhance the equity impact of the tax and build community capacity for retaining the tax in the face of the inevitable opposition from commercial interests. Such complementary strategies include zoning measures to decrease outdoor advertising for sugar-sweetened beverages given that such ads are more common in lower-income neighborhoods (reducing deterrents) (Isgor et al., 2016; Yancey et al., 2009), restrictions on serving sugar-sweetened beverages in preschool programs, emphasizing programs in high-risk communities where this might not happen spontaneously (reducing deterrents), farm-to-school programs that reach children in public schools (increasing healthy options), and infrastructure approaches for increasing availability of acceptable potable water sources in public schools (increasing healthy options).

Healthy food financing initiatives (HFFIs) were a major aspect of the Philadelphia experience and have since been adopted nationwide as ways to improve healthy eating in communities without supermarket access or other good sources of healthy foods at affordable prices. HFFIs provide a more general example of the potential for combining interventions from different categories of the framework. These initiatives are inherently multisectoral in that they draw upon various types of fiscal and other policies in the realm of tax credits and community development to increase equity through food retailing (Chrisinger, 2016). They create venues for positive messaging and experiences through healthy in-store retailing or promotional practices, including taste-testing and food demonstrations (capacity). HFFI’s can also involve healthy food subsidy programs offered under the auspices of SNAP, WIC or other nutrition and food assistance programs, such as coupons or rebates associated with the purchase of fresh fruits and vegetables.

Job creation is one of the most clearly documented community benefits of HFFIs (Chrisinger, 2016). However, reports that these initiatives may not result in improved eating patterns or weight create doubt about their effectiveness on these important public health outcomes (Cummins et al., 2014). This suggests a need to consider the assumptions and mechanisms underlying the presumed health effects of these interventions. For example, consumer capacity-building initiatives, including well-focused in-store retailing initiatives and food and nutrition literacy, may be essential for success. Placing other types of services, such as banking and health care, at the same location (resources) may serve as incentives for people to do their regular shopping at these stores.

As suggested by the Philadelphia case study overall and the example of how HFFI’s implemented in underserved communities might be improved, the equity-oriented framework could also be used retrospectively for program evaluation. Elements of existing initiatives could be assessed for sensitivity to the applicable intervention contexts, complementarity in terms of the four areas of the equity-oriented framework; and potential missing elements that, if added, might improve equity impact. For example, the framework could help with identifying prerequisites for a program to work, such as whether a social marketing program related to healthy eating is only effective in combination with initiatives to increase access to affordable and popular healthy foods in the same community. Alternatively, looking across categories in the framework could lead to recognition of how the outcomes of a program in one category could affect a need in another category. Ideally this would be a positive effect (e.g., opening a new supermarket creates jobs, or greening or murals to improve scenery may reduce street crime). However, the potential to uncover unintended negative consequences must also be considered. For example, a health impact assessment (Cole and Fielding, 2007) of a proposed community development project that

seems otherwise favorable might reveal aspects that need to be modified in order to avoid negative health consequences for some neighborhoods.

Concluding Comments

This equity-oriented obesity prevention action framework, which builds on the APOP framework, was developed to aid in solving obesity as a major community health problem for the populations, subgroups, and communities that face the greatest challenges in achieving and maintaining healthy weight. What it adds is a people-oriented lens where impact depends on mounting and integrating efforts related to improving health options, economic and other resources, building community capacity, and decreasing deterrents to healthy behaviors in circumstances of systematic social disadvantage.

Inequities in social structures and processes are the main drivers of population-level disparities in obesity prevalence, and addressing these drivers is critical for equity in achieving healthy weight. Use of the framework proposed here would also be expected to advance overall health equity and well-being over and above effects on weight, because the resultant types of solutions would be expected to have concurrent benefits that extend outside of the specific domains of food and physical activity. This framework can be used in conjunction with other such frameworks, including Health in All Policies (APHA, n.d.), Collective Impact (Kania and Kramer, 2011), and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Culture of Health Action Model (2015). All of these population health improvement frameworks motivate and guide multisectoral, comprehensive, systems-oriented approaches to advancing community health.

In conclusion, by identifying and calling for integration across four complementary categories of solutions, this framework supports strategy development that works toward additive or synergistic effects on obesity prevention. It is consistent with the principles, processes, and current evidence about the importance of whole community interventions with a deliberate focus on equity when designing and implementing strategies for obesity prevention in the United States and abroad.

References

- Adler, N. E., J. Stewart, S. Cohen, M. Cullen, A. Diez Roux, W. Dow, G. Evans, I. Kawachi, M. Marmot, K. Matthews, B. McEwen, J. Schwartz, T. Seeman, and D. Williams. 2007. Reaching for a healthier life: Facts on socioeconomic status and health in the US. San Francisco, CA: John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Available at: https://macses.ucsf.edu/downloads/Reaching_for_a_Healthier_Life.pdf (accessed August 10, 2020).

- APHA (American Public Health Association). (n.d.). Health in all policies. Available at: https://www.apha.org/topicsand-issues/health-in-all-policies (accessed November 18, 2016).

- Backholer, K., A. Beauchamp, K. Ball, G. Turrell, J. Martin, J. Woods, and A. Peeters. 2014. A framework for evaluating the impact of obesity prevention strategies on socioeconomic inequalities in weight. American Journal of Public Health 104(10):e43-e50. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302066

- Bandura, A. 2006. Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science 1(2):164-180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

- Beauchamp, A., K. Backholer, D. Magliano, and A. Peeters. 2014. The effect of obesity prevention interventions according to socioeconomic position: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews 15(7):541-554. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12161

- Boelsen-Robinson, T., A. Peeters, A. Beauchamp, A. Chung, E. Gearon, and K. Backholer. 2015. A systematic review of the effectiveness of whole-of-community interventions by socioeconomic position. Obesity Reviews 16(9):806-816. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12297

- Braveman, P. 2009. A health disparities perspective on obesity research. Preventing Chronic Disease 6(3):A91. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2722388/ (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Carey, G., B. Crammond, and E. De Leeuw. 2015. Towards health equity: A framework for the application of proportionate universalism. International Journal for Equity in Health 14(1):81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0207-6

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2014. National diabetes statistics report: Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/statistics-report.html (accessed August 10, 2020).

- CDC. 2015. Health, United States, 2014: With special feature on adults aged 55-64. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus14.pdf (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Chrisinger, B. W. 2016. Taking stock of new supermarkets in food deserts: Patterns in development, financing, and health promotion. San Franscisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Community Development Investment Center. Available at: http://www.frbsf.org/community-development/publications/workingpapers/2016/august/new-supermarkets-in-fooddeserts-development-financing-health-promotion/ (accessed November 18, 2016).

- Chung, A., K. Backholer, E. Wong, C. Palermo, C. Keating, and A. Peeters. 2016. Trends in child and adolescent obesity prevalence in economically advanced countries according to socioeconomic position: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews 17(3):276-295. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12360

- Cole, B. L., and J. E. Fielding. 2007. Health impact assessment: A tool to help policy makers understand health beyond health care. Annual Review of Public Health 28:393-412. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.083006.131942

- Cummins, S., E. Flint, and S. A. Matthews. 2014. New neighborhood grocery store increased awareness of food access but did not alter dietary habits or obesity. Health Affairs (Millwood) 33(2):283-291. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0512

- Dawkins-Lyn, N., and M. Greenberg. 2015. Signs of progress in childhood obesity declines. Site summary report. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation NCCOR childhood obesity declines project. Available at: http://nccor.org/downloads/CODP_Site%20Summary%20Report_Philadelphia_public_clean1.pdf (accessed November 18, 2016).

- Frederick, C. B., K. Snellman, and R. D. Putnam. 2014. Increasing socioeconomic disparities in adolescent obesity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 111(4):1338-1342. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321355110

- Hammond, R. A., and R. Levine. 2010. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity 3:285-295. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSOTT.S7384

- Horton, E. S. 2009. Effects of lifestyle changes to reduce risks of diabetes and associated cardiovascular risks: Results from large-scale efficacy trials. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17(Suppl 3):S43-S48. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.388

- Institute of Medicine. 2005. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11015

- Institute of Medicine. 2012. Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13275

-

Institute of Medicine. 2013. Creating Equal Opportunities for a Healthy Weight: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18553

- Institute of Medicine. 2013. Evaluating Obesity Prevention Efforts: A Plan for Measuring Progress. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18334

- Isgor, Z., L. Powell, L. Rimkus, and F. Chaloupka. 2016. Associations between retail food store exterior advertisements and community demographic and socioeconomic composition. Health Place 39:43-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.02.008

- Iton, T., S. Witt, and D. Kears. 2008. Life and death from unnatural causes. Health and social inequity in Alameda County. Oakland, CA: Alameda County Public Health Department.

- Kania, J., and M. Kramer. 2011. Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review (Winter):36-41. Available at: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/collective_impact (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Koh, H. K., J. J. Piotrowski, S. Kumanyika, and J. E. Fielding. 2011. Healthy people: A 2020 vision for the social determinants approach. Health Education & Behavior 38(6):551-557. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198111428646

- Kumanyika, S. K., E. Obarzanek, N. Stettler, R. Bell, A. E. Field, S. P. Fortmann, B. A. Franklin, M. W. Gillman, C. E. Lewis, W. C. Poston, 2nd, J. Stevens, Y. Hong, American Heart Association Council on Epidemology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Committee for Prevention. 2008. Population-based prevention of obesity: The need for comprehensive promotion of healthful eating, physical activity, and energy balance: A scientific statement from American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Interdisciplinary Committee for Prevention (formerly the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science). Circulation 118(4):428-464. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189702

- Kumanyika, S., W. C. Taylor, S. A. Grier, V. Lassiter, K. J. Lancaster, C. B. Morssink, and A. M. Renzaho. 2012. Community energy balance: A framework for contextualizing cultural influences on high risk of obesity in

ethnic minority populations. Preventive Medicine 55(5):371-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.002 - Loring, B., and A. Robertson. 2014. Obesity and inequities in Europe. Guidance for addressing inequities in overweight and obesity. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/obesity-and-inequities.-guidance-for-addressing-inequities-in-overweight-and-obesity-2014 (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Lubrano, A. 2014. Philadelphia rates highest among top 10 cities for deep poverty. Philadelphia Inquirer, September 25. Available at: http://www.philly.com/philly/news/20140925_Phila_s_deep_poverty_rate_highest_of_nation_s_10_most_populous_cities.html (accessed November 18, 2016).

- May, A. L., D. Freedman, B. Sherry, and H. M. Blanck. 2013. Obesity — United States, 1999–2010. MMWR 62(3):120-128.

- Nadolny, T. L. 2016. Soda tax passes; Philadelphia is first big city in the nation to pass one. Philadelphia Inquirer, June 16. http://www.philly.com/philly/news/politics/20160617_Philadelphia_City_Council_to_vote_on_soda_tax.html (accessed November 18, 2016).

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. Summary health statistics. National health interview survey, 2015. Available at: http://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/health_statistics/nchs/nhis/shs/2015_shs_table_a-15.Pdf (accessed December 1,

2016). - Ogden, C. L., M. M. Lamb, M. D. Carroll, and K. M. Flegal. 2010a. Obesity and socioeconomic status in adults: United States, 2005-2008. NCHS Data Brief 50:1-8. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21211165/ (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Ogden, C. L., M. M. Lamb, M. D. Carroll, and K. M. Flegal. 2010b. Obesity and socioeconomic status in children and adolescents: United States, 2005-2008. NCHS Data Brief 51:1-8. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21211166/ (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Ogden, C. L., M. D. Carroll, C. D. Fryar, and K. M. Flegal. 2015. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief 219:1-8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db219.htm (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Robbins, J. M., G. Mallya, M. Polansky, and D. F. Schwarz. 2012. Prevalence, disparities, and trends in obesity and severe obesity among students in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, school district, 2006-2010. Prevention of Chronic Disease 9:E145. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd9.120118

- Robbins, J. M., G. Mallya, A. Wagner, and J. W. Buehler. 2015. Prevalence, disparities, and trends in obesity and severe obesity among students in the school district of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2006-2013. Prevention of Chronic Disease 12:E134. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.150185

- RWJF (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation). 2015. From vision to action. A framework and measures to mobilize a culture of health. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/files/rwjf-web-files/Research/2015/From_Vision_to_Action_RWJF2015.pdf (accessed November 18, 2016).

- Sanger-Katz, M. 2016. Making a soda tax more politically palatable. New York Times, April 3. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/04/upshot/making-a-sodatax-more-politically-palatable.html (accessed November

18, 2016). - Swinburn B., G. Egger, and F.Raza F. 1999. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Preventive Medicine. 9(6 Pt 1):563-70. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1999.0585

- Taylor, L. A., C. E. Coyle, C. Ndumele, E. Rogan, M.Canavan, L. Curry, and E. H. Bradley. 2015. Leveraging the social determinants of health. What works? Available at: http://bluecrossfoundation.org/publication/leveraging-social-determinants-health-what-works (accessed November 18, 2016).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2016. Quick facts. Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania. Available at: http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/42101,00 (accessed November 13, 2016).

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2000. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization Technical Report Series 894:i-xii, 1-253. Available at: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/WHO_TRS_894/en/ (accessed August 10, 2020).

- WHO. 2013. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020. Available at: http://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/ (accessed December 1, 2016).

- Wing, R. R., W. Lang, T. A. Wadden, M. Safford, W. C. Knowler, A. G. Bertoni, J. O. Hill, F. L. Brancati, A. Peters, and L. Wagenknecht. 2011. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 34(7):1481-1486. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-2415

- Yancey, A. K., B. L. Cole, R. Brown, J. D. Williams, A. Hillier, R. S. Kline, M. Ashe, S. A. Grier, D. Backman, and W. J. McCarthy. 2009. A cross-sectional prevalence study of ethnically targeted and general audience

outdoor obesity-related advertising. Milbank Quarterly 87(1):155-184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00551.x - Zomer, E., K. Gurusamy, R. Leach, C. Trimmer, T. Lobstein, S. Morris, W. P. James, and N. Finer. 2016. Interventions that cause weight loss and the impact on cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews 17(10):1001-1011. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12433

Food and Nutrition, Global Health, Longevity, Obesity, Population Health, Public Health