Components of the Next Generation of Integrated Care

Introduction

The purpose of this Commentary is to explore the ways in which the key elements of integrated care (integrating behavioral health care with primary care in an effort to improve and streamline complete care for the patient) are being incorporated into the health care system and to examine new elements that have emerged in the years since the field of integrated care was established in the 1990s [1]. In an integrated care approach, behavioral health and primary care providers work as a team to address patient concerns, whether that takes place in the same practice setting or through distance-based modalities. This team-based approach allows for easier access to care, the potential for more effective care coordination, use of an integrated medical record, and the inclusion of a range of professional and paraprofessional care providers. When services are provided in a coordinated manner, individuals are more likely to have their medical and behavioral health needs addressed [2].

As evidence demonstrating the value of integration for improving access to care grows, consideration needs to be given to the next generation of integrated care. The authors of this commentary were interested in hearing from executives in managed behavioral health care organizations and primary care safety net providers on whether the identified elements of integrated care are sufficient today or whether additional elements need to be considered.

Background, Concept, and Elements of Integration 1.0

The benefit of including behavioral health providers on care teams, not only for specific behavioral health concerns, but also for physical health concerns, is well documented. For example, depression treatment for those with diabetes in a primary care setting leads to lower total health care costs ($896 per patient over 24 months) [3]. Access to integrated patient data [4], the use of screening tools [5], and a systematic review of patient care all support improved patient outcomes [6].

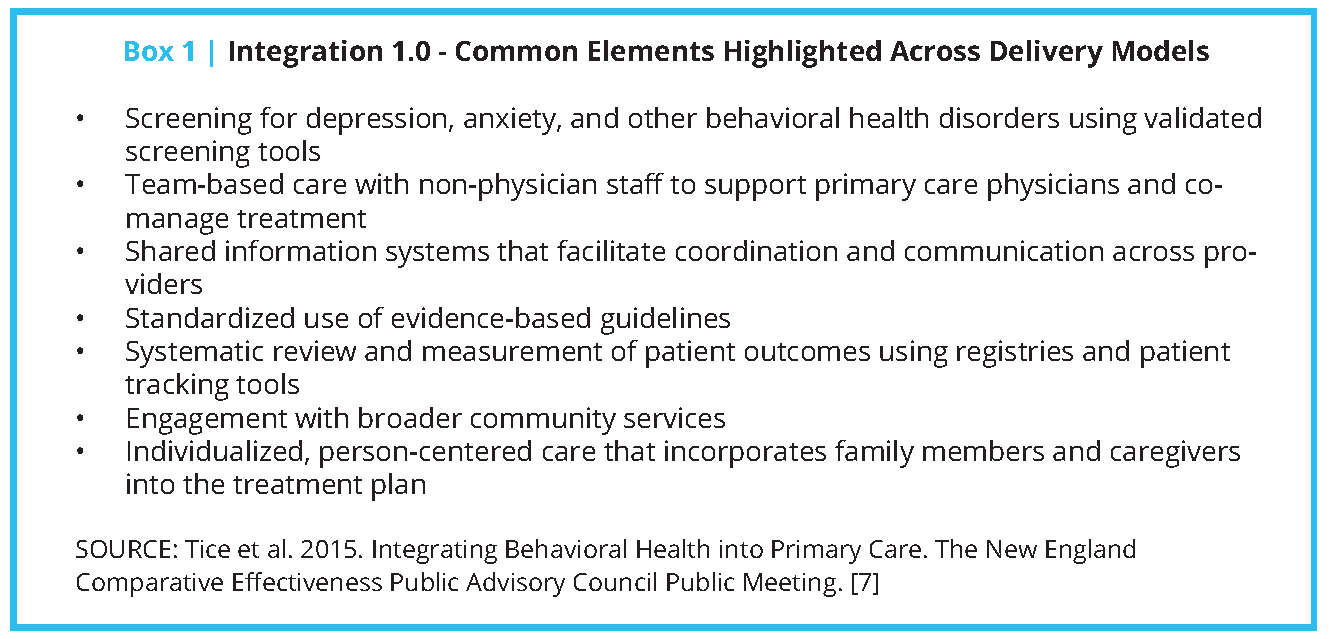

In 2015, the Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council (the Council) studied the evidence on the clinical effectiveness and value of the integration of behavioral health services in primary care settings. As the basis for this work, the Council identified common elements across integrated care models. The authors of this paper refer to these common elements as Integration 1.0 (see Box 1) [7].

How widespread is fully integrated care? That’s not an easy question to answer. One study using data from 2018 estimated that community-based physicians and behavioral health providers are co-located (working at the same location but not necessarily fully integrated) 44 percent of the time. But within this statistic, there are hidden differences—the co-location rate was 46 percent in urban areas and 26 percent in rural parts of the country, with regional variations evident as well [8].

To better understand this landscape, two focus groups were conducted with managed behavioral health care executives affiliated with the Association for Behavioral Health and Wellness and current/former leadership from safety net primary care provider organizations that have received grant funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration (see Appendix A). These focus groups were asked three questions:

- Which elements of Integration 1.0 are you finding effective?

- How many of the Integration 1.0 elements are you able to use when caring for patients in an integrated manner?

- From your experience and perspective, what does the field need to be thinking about as integration continues to evolve (i.e., what is missing)?

The Idea of a New Approach – Integration 2.0

Both focus groups affirmed the components of integration identified in the Council study discussed above. While there was unanimity among all participants in our discussions regarding the key elements of Integration 1.0, there were some concerns about how well specific elements have been adopted in practice.

One persistent message among the focus group conversations was centered on the need for broader adoption of Integration 1.0. Participants suggested using coaching to help organizations establish their integrated model of care and expand on initial integration efforts. Coaching models are flexible and can help a practice adapt integration to its specific workforce profile and the needs of the organization. Engagements can take place on-site or from a distance. Early stages of coaching will often involve some form of comprehensive analysis followed by check-ins involving key clinical and/or management staff or the whole team [9]. Coaching can involve individual practices or several clinical practices within a larger network [10].

One constant challenge in implementing integrated care has been the ability to replicate existing models in other practice settings. Representatives of both groups questioned whether evidence-based practices are being uniformly implemented and whether outcomes are measured in a consistent manner across provider organizations.

Both groups felt that lack of adoption of Integration 1.0 could be attributed in many respects to limitations in the flow of information across different types of care providers within organizations as well as the need for payment mechanisms that can support sustainable integration. Participants expressed concern about the ability to share information across systems (data exchange) and uncertainty about what information could be shared legally, especially as it relates to treatment for substance use disorders (i.e., in a manner consistent with the confidentiality provisions in state and federal [42 CFR Part 2] substance use disorder privacy regulations). Even internal access privileges by primary care and behavioral health care providers within the same organization can be a challenge because electronic medical records may not be well designed for integrated, team-based documentation.

Many of the focus group participants indicated that knowing which behavioral health services and provider types will be reimbursed by which payer(s) remains a primary concern, as payment has a direct impact on the specific behavioral health services that are successfully integrated into care delivery models. Both behavioral health care executives and safety net providers indicated that traditional fee-for-service models of reimbursement have not given them the flexibility and incentives they need to effectively develop integrated models of care. The collaborative care model [11], for example, has identified care coordination as an especially important component of integration—but how do we ensure adequate funding for that particular component of a proven model such as collaborative care? There were also questions concerning prohibitions that may still exist regarding reimbursing more than one medical/behavioral health visit on the same day.

What Might Integration 2.0 Look Like?

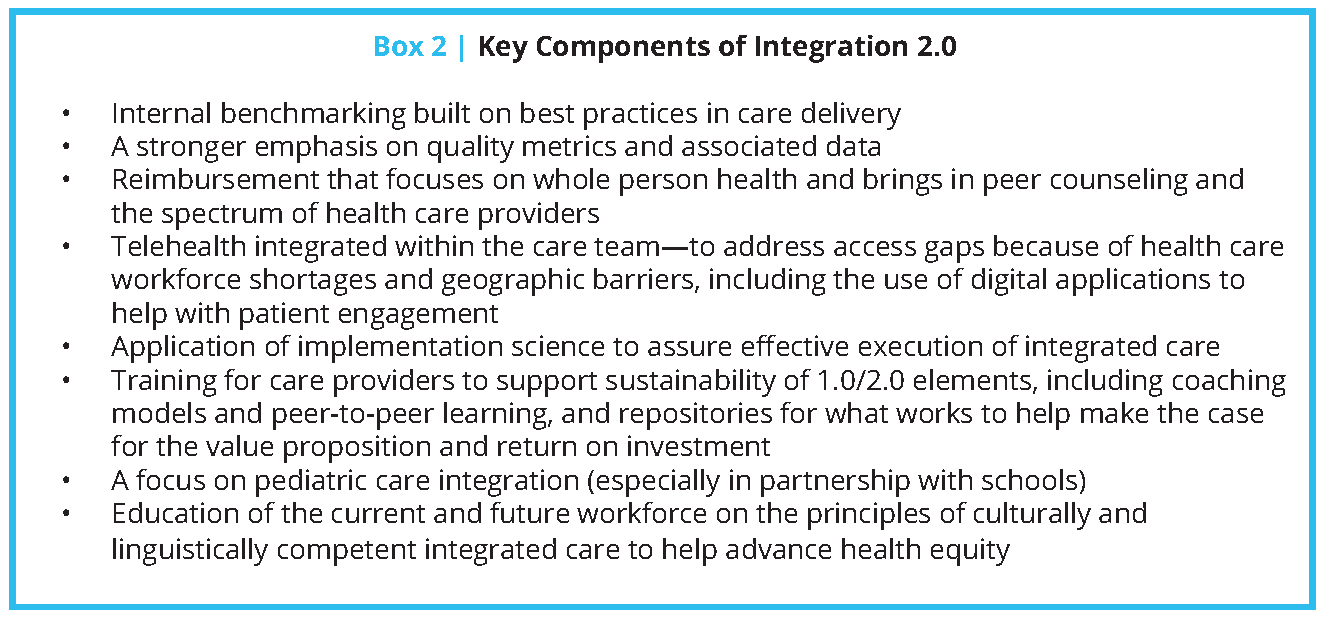

When the discussions turned to what might be added to the existing list of core elements of integrated care, the focus group participants identified a number of components that they felt should be considered as the field moves toward Integration 2.0, including:

- Internal benchmarking built on best practices in care delivery

- A stronger emphasis on quality metrics and associated data

- Reimbursement that focuses on whole person health and brings in peer counseling and the spectrum of health care providers

- Telehealth integrated within the care team—to address access gaps because of health care workforce shortages and geographic barriers, including the use of digital applications to help with patient engagement

- Application of implementation science to assure effective execution of integrated care

- Training for care providers to support sustainability of 1.0/2.0 elements, including coaching models and peer-to-peer learning, and repositories for what works to help make the case for the value proposition and return on investment

- A focus on pediatric care integration (especially in partnership with schools)

- Education of the current and future workforce on the principles of culturally and linguistically competent integrated care to help advance health equity

Underlying Issues Related to Financing Integrated Care

The focus group participants emphasized that sustainable and comprehensive financing is essential to advance Integration 2.0. The development of alternative payment models (APMs) is a promising sign that will hopefully align with the next generation of integrated care. APMs in use today include multi-payer collaborations, bundled payments, and accountable care organizations. APMs have the potential to promote sharing of information across clinicians on the patient’s behalf. They do this by providing revenue not tied to a specific service, but rather based on treating the whole person and based on case management fees, capitation, and/or payments for meeting performance expectations. Such models also support hiring a range of staff including peer counselors and recovery coaches.

Conclusion

The focus groups identified several components of integration that should be considered as models of care evolve, including a stronger emphasis on metrics and benchmarking, pediatric integration, telehealth, and implementation science, among others (see Box 2). These groups also emphasized challenges in effective implementation of existing components of integration. We know that spending on behavioral health care improves physical health and decreases physical health care costs; we need to clearly define the value proposition and the return on investment of integration [12].

Health reform initiatives in recent years—which focus on paying for high value care over high volume care—provide an opportunity for improving integration. Payment models being advanced today should encourage the adoption of key elements of Integration 2.0 as we move into the new decade.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! In an integrated care approach, behavioral health and primary care providers work as a team to address patient concerns. Authors of our new #NAMPerspectives commentary identify what it will take to achieve the next generation of integrated care: https://doi.org/10.31478/202011e

Tweet this! In an integrated care approach, behavioral health and primary care providers work as a team to address patient concerns. Authors of our new #NAMPerspectives commentary identify what it will take to achieve the next generation of integrated care: https://doi.org/10.31478/202011e

![]() Tweet this! Evidence showing the benefit of integrated care, or when primary care providers and behavioral health specialists work together, is growing. Key priorities for the next generation of integrated care are outlined in a new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202011e

Tweet this! Evidence showing the benefit of integrated care, or when primary care providers and behavioral health specialists work together, is growing. Key priorities for the next generation of integrated care are outlined in a new #NAMPerspectives: https://doi.org/10.31478/202011e

![]() Tweet this! Coaching and using existing models as templates can help more organizations adopt integrated care, and broader uptake of this consolidated approach to patient care could improve patient outcomes. Read more: https://doi.org/10.31478/202011e

Tweet this! Coaching and using existing models as templates can help more organizations adopt integrated care, and broader uptake of this consolidated approach to patient care could improve patient outcomes. Read more: https://doi.org/10.31478/202011e

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- Katon, W., M. Von Korff, E. Lin, E. Walker, G. Simon, T. Bush, P. Robinson, and J. Russo. 1995. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 273(13): 1026-1031, Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7897786/ (accessed October 16, 2020).

- Kwan, B. M., A. B. Valeras, S. B. Levey, D. W. Nease, and M. W. Talen. 2015. An Evidence Roadmap for Implementation of Integrated Behavioral Health under the Affordable Care Act. AIMS Public Health 2(4): 691-717. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2015.4.691

- Katon, W. J., J. Unützer, M.-Y. Fan, J. W. Williams, M. Schoenbaum, E. H. B. Lin, and E. M. Hunkeler. 2006. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care 29(2): 265-70. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1572

- Reiss-Brennan, B., K. D. Brunisholz, C. Dredge, P. Briot, K. Grazier, A. Wilcox, L. Savitz, and B. James. 2016. Association of Integrated Team-Based Care with Health Care Quality, Utilization, and Cost. JAMA 316(8):826-834. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.11232

- Mulvaney-Day, N., T. Marshall, K. D. Piscopo, N. Korsen, S. Lynch, L. H. Karnell, G. E. Moran, A. S. Daniels, and S. S. Ghose. 2018. Screening for Behavioral Health Conditions in Primary Care Settings: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine 33: 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4181-0

- AIMS Center. 2020. Identify a Behavioral Health Patient Tracking System. Available at: https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/implementation-guide/plan-clinical-practice-change/identify-behavioralhealth (accessed October 16, 2020).

- Tice, J. A., D. A. Ollendorf, S. J. Reed, K. K. Shore, J. Weissberg, and S. D. Pearson. 2015. Integrating Behavioral Health into Primary Care. The New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council Public Meeting. Available at: http://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/BHI-CEPAC-REPORT-FINAL-VERSION-FOR-POSTING-MARCH-23.pdf (accessed October 16, 2020).

- Richman, E. L., B. M. Lombardi, and L. D. Zerden. 2020. Mapping colocation: Using national provider identified data to assess primary care and behavioral health colocation. Families, Systems, & Health 38(1): 16-23. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000465

- Bhat, A., I. M. Bennett, A. M. Bauer, R. S. Beidas, W. Eriksen, F. K. Barg, R. Gold, and J. Unützer. 2020. Longitudinal Remote Coaching for Implementation of Perinatal Collaborative Care: A Mixed-Methods Analysis. Psychiatric Services 71(5): 518-521. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900341

- Henwood, B. F., E. Siantz, K. Center, G. Bataille, E. Pomerance, J. Clancy, and T. P. Gilmer. 2020. Advancing Integrated Care through Practice Coaching. International Journal of Integrated Care 20(2):15. http://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.4737

- AIMS Center. 2020. Principles of Collaborative Care. Available at: https://aims.uw.edu/collaborativecare/principles-collaborative-care (accessed October 16, 2020).

- Melek, S. P., D. T. Norris, J. Paulus, K. Matthews, A. Weaver, and S. Davenport. 2018. Potential economic impact of integrated medical-behavioral healthcare. Milliman Research Report. Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Professional-Topics/Integrated-Care/Milliman-Report-Economic-Impact-Integrated-Implications-Psychiatry.pdf (accessed October 16, 2020).