Competencies and Tools to Shift Payments from Volume to Value: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

Introduction

Health reform remains at the forefront of US policy debates because of continued growth in public and private health care spending alongside increasing capabilities of medical care—as well as persistent evidence of inefficiencies and substantial variance in use, cost, and quality (NASEM, 2016). Bipartisan support has emerged for moving away from fee-for-service (FFS) payment because of its failure to support many innovative approaches to care delivery and its administrative burdens on clinicians and patients.

Alternative payment models have proliferated in federal, state, and commercial initiatives, including the Medicare and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015 (US Congress, 2015), with the hope of aligning financial support with higher-value care. The Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network has described a variety of payment reforms (Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network, 2016) and accompanying delivery models that represent a shift away from FFS, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), fixed bundled payments for episodes of care, and primary care medical homes with shared savings. It is a reflection of the expansion of such alternative payment models (APMs) that as of January 2016 847 ACOs collectively provide coverage to over 28.3 million Americans (Figure 1) (Muhlestein and McClellan, 2016). With similar models not only proliferating in traditional Medicare but in Medicare Advantage plans, Medicaid programs, and commercial and employer plans, most Americans probably will be affected by one or more of those payment models in the near or not too distant future.

Despite the promise and enthusiasm, early results have been mixed. Some ACOs have demonstrated notable improvements in care quality with financial success, but most participants in Medicare’s major APMs have not yet realized large savings (Dale et al., 2016; McWilliams et al., 2016). Early APM results suggest that improving quality does not generally lead to better financial performance. Consequently, there has been enormous interest in improving the design of APMs and the data available to support health care organizations in APMs.

Value-based payment policies will continue to evolve as evidence on their effectiveness accumulates, but even with further policy refinements, the “how” of improving care, reducing costs, and thus succeeding under new financing models is not well understood. Some assume that if the payment model is “right,” the proper and corresponding care models will emerge naturally. But many organizations do not have a good understanding of where to start or how to proceed in the transformation process, and many of the tools and approaches are of uncertain value. Pressure is rising to delay MACRA and other payment reforms, especially for smaller health care organizations and those serving vulnerable populations, because providers are not ready. From the standpoint of achieving the goals of higher-value care, policies to support care-delivery transformation are as critical as effective payment reforms.

Challenges to and Progress Toward Defining and Supporting Competencies for Value-Based Health Care

US health care organizations have well-developed capabilities for FFS payment systems: scheduling, coding, billing, electronic data transmission, reporting, and other competencies to support the conduct and payment of covered services. In contrast, proficiencies in preventing disease and optimally managing the health of a population at the lowest possible cost have not yet been widely identified or applied, and most organizations are unsure about how and how much to invest in new capabilities.

Collaboratives, such as the Accountable Care Learning Collaborative (ACLC) and others illustrated in Table 1, focus on addressing those key issues, cost implications, and barriers to advancing accountable care. The collective goal for many groups is to help health care providers to develop needed competencies for care-delivery reform and to support providers in succeeding in value-based payment models. Many organizations are undertaking similar efforts on their own, but the unique benefit of collaboratives is the aggregation of both public and private evidence and expert opinion on how to improve care. Collaboratives can create a uniform set of best practices and strategies for success. For accountable care to progress, the collective knowledge concerning value-based care competencies needs to be aggregated, evaluated, and broadly disseminated.

Like many of the other groups in Table 1, the ACLC has drawn from the experiences of public and private collaborative efforts to develop a widely applicable framework describing the competencies that risk-bearing entities must develop to succeed in accountable care (ACLC Competencies, 2016). The ACLC’s strategic goal is to help organizations to identify their current competency gaps and then to link them to relevant resources for developing those competencies.

The creation of the ACLC competency framework involved a process of preliminary identification of major competency areas, the commissioning of a set of collaborative workgroups to conduct an evidence and resource review in each area, an iterative consensus process in each workgroup to identify key capabilities and best practices, and a high-level review to refine the overall structure of the identified competencies. The competencies could form the basis of a capability-assessment tool for providers to use in determining their readiness to take on value-based payments and the basis of a resource set for linking providers to tools, resources, and supporting organizations that can help them to develop needed competencies.

The ACLC has identified seven primary competency domains, as shown in Table 2. Each competency domain can be expanded into a more complete set of capabilities, as illustrated in Figure 2. The framework illustrates the magnitude of the challenges facing health care organizations; it is not surprising that few have succeeded (Health Leaders Media, 2016). The framework provides a foundation for health care organizations to use in identifying the key tasks ahead of them and in taking some practical and feasible steps that are likely to succeed in enabling them to move forward.

The goal of the competency framework is to help organizations to understand the totality of activities that they need to undertake and, more important, where to start and how to take initial steps that are needed to succeed. That point is illustrated by the following list of the five essential competencies enumerated within the integration strategies and partnerships category in the Quality domain:

- Develop a process of effective collaboration with value-focused partners throughout the health care spectrum.

- Ensure that patients, families, providers, and care team members are involved in quality-improvement activities.

- Capture and report data relevant to cost, processes of care and care delivery, medical and health outcomes, and service outcomes in an integrated and standard manner.

- Build a team of operations experts and clinical continuous quality-improvement experts to guide the work of improvement teams from within the organization.

- Participate in a formal quality collaborative with other health care organizations and strategic partners that necessitates sharing of data and knowledge.

For health care organizations seeking to move to value-based care, the specific competencies provide the genesis for leveraging partnerships and care integration to maximize the quality of care provided for a given population.

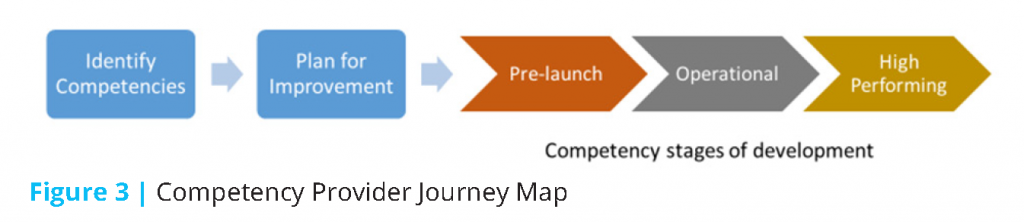

Figure 3 represents the competency journey map that provides context for how providers move from identifying gaps in their understanding of the competencies needed for value-based care through the stages of development that lead to mature capabilities.

Vital Directions to Accelerate the Development of Health Care Capabilities to Succeed in Value-Based Payment Models

Even with resources like those being developed in the ACLC and other collaboratives, delivery reform is challenging. Policy support is needed to refine this type of competency framework by improving the evidence underlying it and encouraging organizations to draw on the resources.

Given governments’ role as major purchasers of health care, federal and state payment policies have been a primary policy focus, as evidenced by Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Secretary Sylvia Burwell’s 2015 announcement to shift 80% of care into value-based purchasing models by 2018 and related initiatives, such as the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network. However, despite the need for payment reform, without organizations that are able to function well with new payment models, progress both in payment and in delivery of higher-value health care will be slow and cumbersome.

Public policy needs to put comparable effort into identifying what works and what does not work in delivering care in value-based payment models and into supporting health care providers and the organizations working with them to develop the capabilities that they need to succeed. Government does not have the capacity or expertise to dictate what works, but it can facilitate networks to find and spread solutions more quickly.

There is also a need for policy makers to support the development of a clearinghouse to link health care providers to resources that can help them to develop needed competencies. The collaborative efforts would have the goal of assisting federal and state policy makers to identify and adopt lessons learned from data and experience in the varied collaborations about how policies can support effective delivery reform better.

Recommendations for Vital Directions

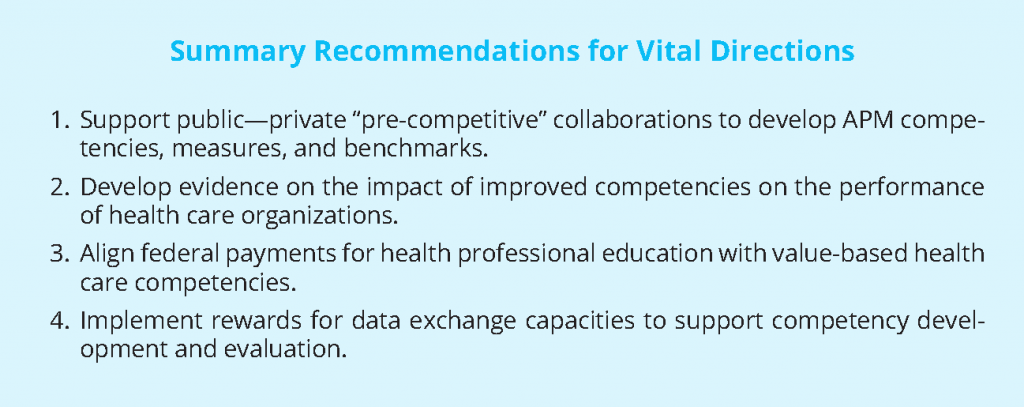

Policy makers should match support for improving the design and evaluation of payment-reform models with commensurate support for health care providers to develop the competencies needed to succeed. We highlight four vital directions below.

- Support Public-Private “Precompetitive” Collaborations to Accelerate the Development of Alternative Payment Model Competencies, Measures, and Benchmarks. We encourage federal and state governments to support and participate in privately led collaborations to accelerate delivery reform. Collaborations aiming to provide tools and resources to accelerate the development of APM competencies include such initiatives as Premier’s Population Health Management Collaborative, the Health Care Transformation Task Force, the ACLC, and the National Academy of Medicine’s Leadership Consortium on Value and Science-Driven Health. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and DHHS should participate actively, and the federal government should provide financial support for using the initiatives to develop better publicly available resources for providers. For example, CMS “learning networks” for particular Medicare payment reforms should be conducted in closer collaboration with private-sector efforts in similar payment reforms with specific goals for improved resources for providers. High priority should be attached to better tools for different types of providers to assess gaps and to track and evaluate progress in APM capabilities through the development, refinement, and wider use of measures of key care-delivery competencies. Publicly supporting collaborations could help to facilitate the identification of competencies and value-based terminology, articulate ways to measure organizational performance, and direct the dissemination of the findings.

- Develop Evidence on the Effects of Improved Competencies on the Performance of Health Care Organizations. Collaboration in competency assessment and development should be based on a stronger foundation of empirical evidence. Organizations that apply the same competency framework can more easily benchmark themselves against other, similarly situated organizations, and the framework can enable more valid analyses of whether proprietary tools and approaches are helping to improve capabilities. This work will also support research studies on how organizational capabilities translate into improvements in quality and cost, which will provide needed evidence to guide further payment reforms and competency development work. The federal government should support research on the impact of improved competencies on organizational quality and cost performance. The improving evidence base will lead to a better understanding of which competencies are needed for success and the best ways to develop them.

- Align Federal Payments for Health-Profession Education with Value-Based Health Care Competencies. Federal payments for health-profession education with value-based health care competencies will help more medical schools and other health-care professional education programs to make needed changes to reflect the new kinds of skills that health professionals need to succeed in a system focused on value (Scheibal, 2016). Some have already begun to change. The University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, for example, changed its name and curriculum in 2005 to emphasize the need to treat the whole patient rather than just a patient’s physical condition (Jablow, 2015). New medical schools, including Dell Medical School of the University of Texas at Austin and the recently announced Kaiser Medical School, are implementing fundamentally different approaches to clinical education that are much better aligned with accountability for population health. Continuing-medical-education activities are also increasingly focusing on new care competencies. Despite those efforts, however, federal educational support is only slightly aligned with the emerging national priorities in care delivery.

- Implement Rewards for Data-Exchange Capacities to Support Competency Development and Evaluation. Health information technology (HIT) is the backbone of success in patient-centered delivery reforms that improve quality and lower cost. In building on the interoperability roadmap developed by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (DeSalvo, 2015), it is important for CMS to focus payment policies for HIT more directly on “use case”–demonstrated competencies in data exchange and to reduce administrative burdens and barriers to data exchange caused by some interpretations of current privacy rules.

Conclusion

American health care needs to be reformed to bend the cost curve and to deliver better, less expensive care to patients, which is increasingly possible. Sharing solutions and collaborating on effective methods for reform throughout the industry not only can reduce disruptions in patient care but will encourage greater competition and collaboration on value in health care.

Federal and state leaders have an opportunity to support those changes by complementing payment reform with provider support in care-delivery transformation. Given the complex infrastructure needs and competencies necessary for successful delivery reform, without support many providers may fail to evolve successfully, and this would slow progress. Government can mitigate failures and increase successes by advocating for and participating in industry collaborations and by adopting the resulting knowledge in regard to value-based care competency measurement and benchmarking, shared competency evidence development, value-based health care education reform, and increasing access to data available through HIT.

The collective state of and spending on American health care has created a small window for the private and public sectors to coalesce around the adoption of value-based care. The transformation away from FFS payments will not be without its challenges, but by incorporating the above recommendations related to greater competency development by providers, policy makers can make important contributions to the sustainability of value-based payment reforms.

References

- ACLC Competencies. 2016. Available at: http://www.accountablecarelc.org/aclc-competencies (accessed August 7, 2016).

- Dale, S. B., A. Ghosh, D. N. Peikes, T. J. Day, F. B. Yoon, E. F. Taylor, K. Swankoski, A.S. O’Malley, P.H. Conway, R. Rajkumar, M.J. Press, L. Sessums, and R. Brown. 2016. Two-year costs and quality in the comprehensive primary care initiative. New England Journal of Medicine 374(24):2345-2356. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1414953

- DeSalvo, K. 2015. Connecting health and care for the nation: A shared nationwide interoperability roadmap. Available at: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hie-interoperability/nationwide-interoperability-roadmap-final-version-1.0.pdf (accessed August 22, 2016).

- Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network. 2016. Alternate Payment Model (APM) Framework: Final White Paper. Available at: https://hcp-lan.org/groups/apm-fpt/apm-framework/ (accessed August

22, 2016). - HealthLeaders Media. 2016, July. Case B. Value-based readiness: Building momentum for tomorrow’s healthcare. Available at: http://www.healthleadersmedia.com/report/intelligence/value-based-readiness-building-momentum-tomorrow%E2%80%99shealthcare (accessed August 22, 2016).

- Jablow, M. 2015. The public health imperative: Revising the medical school curriculum. Available at: www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/may2015/431962/public-health.html (accessed August 22, 2016).

- McWilliams, J., L. A. Hatfield, M. E. Chernew, B. E. Landon, and A. L. Schwartz. 2016. Early performance of accountable care organizations in Medicare. New England Journal of Medicine 374:2357-2366. https://doi.org/10.1056/

NEJMsa1600142 - Muhlestein, D., and M. McClellan. 2016. Accountable care organizations in 2016: Private and public-sector growth and dispersion. Health Affairs blog, April 21. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/04/21/accountable-care-organizations-in2016-private-and-public-sector-growth-and-dispersion/.

- NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. The role of public-private partnerships in health systems strengthening: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21861

- Scheibal, S. 2016. Leading health care transformer joining Dell Med. UT News, The University of Texas at Austin. Available at: http://news.utexas.edu/2016/06/22/health-care-transformer-joining-dell-med (accessed August 23, 2016).

- U.S. Congress. 2015. Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, P.L. 114-10. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2/text/pl (accessed August 22, 2016).