Community-Based Models of Care Delivery for People with Serious Illness

The 20th century saw remarkable improvements in life expectancy (NIA, 2011). Improvements in access to clean water, disease screening and prevention, the discovery of antibiotics and vaccines, development of organ transplantation, and advances in treatment for heart disease and cancer have all contributed to an expectation that Americans will live long lives in generally good health.

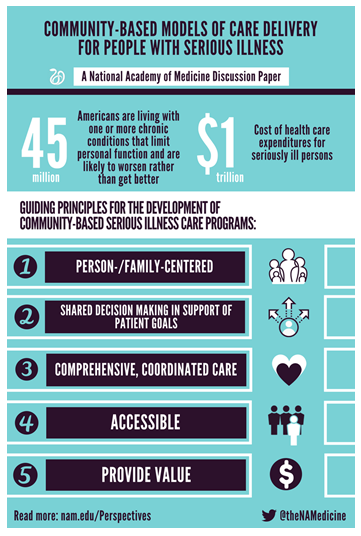

A concomitant change has been that most Americans will now experience a substantial period of living with serious illness, mostly progressive and life-limiting. An estimated 45 million Americans are living with one or more chronic conditions that limit personal function and are likely to worsen rather than get better (IOM, 2015; NASEM, 2016). Although representing only 14 percent of the population, these seriously ill persons account for 56 percent of all health care expenditures—almost $1 trillion (IOM, 2015). While the benefit of curative treatments for people living with serious illness is often limited, our health care delivery system remains almost exclusively focused on the treatment of acute and reversible illness, rather than on supporting quality of life and daily functioning. This has led to a gap between what people need and want from medical care and what they experience. When asked, most people prioritize quality of life over the extension of life if the interventions needed to try to prolong life reduce quality (Cambia, 2011). Yet, many experience intense use of hospital care in the last year of life, with nearly 30 percent spending time in the intensive care unit during the month preceding death (Teno, 2013).

People with serious illness are not a homogeneous group. For the purposes of this discussion paper, the authors define people with serious illness as those with complex and pressing care needs due to a particular disease, e.g., persons with metastatic lung cancer or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis who have breathing difficulty. The definition also includes people who have some years of self-care disability, often at the ends of their lives, from conditions such as cognitive or neuromuscular impairment, strokes, organ system failures, frailty of old age, or other conditions.

Most people with serious illness are in need of both health care and social supports such as access to food, housing, personal care, transportation, and financial support. In addition to disease-focused medical care, most people need symptom relief (e.g., pain, dyspnea, and depression), care coordination and communication over time and across settings, and information and assistance in making difficult decisions. Such expertise in symptom management, shared decision making, and care coordination are features of what is known as palliative care (Meier, n.d.). The field includes primary palliative care (i.e., features integrated into usual care provided by primary and specialty care physicians, nurse practitioners, and others) and specialty palliative care (i.e., care provided by palliative care specialists, geriatricians, and others to the sickest individuals, including those enrolled in hospice).

Although palliative care is now available in most hospital and hospice settings, access to community-based palliative care (at home, in nursing homes, and in office practices) is largely absent in the United States. The population of people with serious illness is substantially broader than those who are hospitalized and those who qualify for hospice. Hospice requires that the person have a prognosis for survival of 6 months or less, as well as a willingness to forego “curative” disease-focused treatments, which leads to late referrals and gaps in access to palliative care for people earlier in the course of illness.

Caring for people with serious illness requires building new community-based care models that:

- integrate the currently fragmented array of social supports and primary, specialty, and hospice services available in most communities;

- broaden the scope of palliative care beyond hospitals and into patient homes, nursing facilities, and office practices;

- make use of telehealth;

- expand the capacity and coordination of supportive social services along with medical care; and

- provide supports for family caregivers.

We use the term community-based serious illness care programs to refer to the growing number of programs that strive to provide this kind of comprehensive care to people with serious illness who reside in community settings. Other terms sometimes used to refer to these types of programs include: community-based palliative care, geriatric team care, and advanced care programs.

In this discussion paper, we identify guiding principles and core components of community-based serious illness care programs, provide an overview of some innovative model programs, and discuss key issues moving forward. When possible, we use the term person rather than patient, in order to underscore the centrality of the person beyond the disease label.

Guiding Principles and Core Competencies

Persons with serious illness and their families have medical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs to be met in the community setting. High-quality programs share common foundational elements necessary to match services to population needs. We will first describe guiding principles that are inherent to the ideal community-based model program. Next, we will discuss core competencies that these programs must possess to provide high-quality care.

Guiding Principles

Building on the work of others (National Consensus Project, 2013; NQF, 2016), we have identified key principles that should guide the development of community-based serious illness care programs.

Person-/Family-Centered

First and foremost, serious illness care programs should be driven by the priorities and goals of the person and family. Accommodation should be made to tailor services that are culturally responsive and language-concordant. The program should support the family unit as defined by the person. Person- and family-centeredness should continue through the end of life and include bereavement supports for the family and others close to the person who has died.

Shared Decision Making in Support of Patient Goals

Care delivery should be guided by a care plan that is focused on goals derived from a communication process that elicits the evolving values and preferences of the person and his/her family over time. An initial comprehensive assessment should be conducted to determine the person’s priorities and concerns, identify gaps in the quality of care, and guide treatment goals. There should be adequate access to disease-specific information on treatment options and pros and cons in the context of personal priorities and goals to support personal control and autonomy. High-quality medical decision making requires person and family education about what to expect in terms of the disease trajectory, prognosis, and anticipated complications.

Comprehensive, Coordinated Care

People with serious illness have complicated needs. Many, if not most, require both health care and social supports (e.g., home health aides, home-delivered meals). Not all people have family caregivers, and even when caregivers are available, respite and social services are usually needed to support families and fill in the gaps. Serious illness care programs must be able to arrange for the provision of both health care and social services. For people of modest financial means, this will necessitate building relationships with local social service agencies.

Although the goal of community-based programs is to allow people to remain in their homes as long as they desire, this is not always possible. People with serious illness are at higher risk of frequent transitions from one care setting to another. Acute events may lead to emergency department or hospital visits or specialist outpatient care outside of the primary community-based program. A high-quality program coordinates and communicates with primary and specialty care to reinforce and enhance care across transitions.

Accessible

Community-based serious illness care programs should be available in all communities and accessible to all people with serious illness. This may require some degree of regional planning and coordination to ensure that local capacity is adequate to meet the needs of residents with serious illness; that all people with serious illness, regardless of insurance status, have access to serious illness care programs; and that insurance plans provide coverage and adequate payment for the services provided by serious illness programs.

It will also be important for serious illness care programs to be proactive in identifying and reaching out to all people in need of services, through processes embedded in comprehensive population health management. For some situations, the fact of serious illness is obvious, e.g., in the case of metastatic pancreatic cancer or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with breathing difficulty. But for others, the boundary between ordinary illness and serious illness is a matter of degree and context, e.g., an elderly person with early frailty who lives with an adult daughter and gradually loses ground over years, eventually becoming completely dependent in all activities of daily living before dying of “natural causes.” For gradually worsening courses like these, serious illness programs have to create operational definitions for the populations they intend to serve.

Provide Value

To be sustainable over the long run, community-based programs must provide value and have a sustainable financial model, as noted above. A program must be able to demonstrate that it can provide high-quality care as evidenced by measures of care outcomes and patient and family perceptions, while at the same time managing costs. High-value programs carefully design care processes, deploy highly effective care teams, make wise use of technology, recognize and support the contributions of caregivers, and mobilize and buttress the resources of social service agencies by building mutually supportive partnerships.

A key challenge for some serious illness care programs, especially those in rural parts of the United States, is managing the cost of delivering home-based services to a geographically dispersed population. Strategies for managing the cost of travel time by care team members include the use of telehealth services and coordinated approaches to designating particular geographic service areas for serious illness programs.

Core Competencies

Achievement of the guiding principles for model community-based serious illness care programs requires a set of core competencies. These competencies set the standard for a high-quality program.

Identification of the Target Population

Critical to a successful program is selecting the appropriate target population. Research suggests that people with one or more serious illnesses, at least one hospital admission in the prior 12 months and/or residence in a nursing home, and functional impairment have a 47 percent risk of hospitalization and a 28 percent risk of death in the subsequent year (Kelley, 2017). Programs will benefit from screening tools that are both sensitive (i.e., identify as many of those at risk as possible) and specific (i.e., exclude individuals who do not need services or are unlikely to benefit from them).

For practical purposes, most model delivery programs target persons who are either receiving services from a particular provider organization or insured by a particular insurer, or both. Most serious illness programs identify eligible persons based on clinical and health status characteristics (diagnosis, physical and cognitive functioning, prognosis), combined with information on past health care utilization. Programs vary in the extent to which consideration is given to social issues (e.g., availability and capacity of caregivers, caregiver burden, housing, food security, and transportation). Information on functional status, while a critical predictor of future need, is not currently easily available either through claims data or medical records. Some programs, such as the state-based Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly that care for dual-eligible persons insured by Medicaid and Medicare, provide individual assessments to establish severity of disability and (sometimes) the likely future course, so as to provide the person with appropriate supportive services. The Veterans Health Administration defines eligibility for its Home-Based Primary Care program on the clinical assessment that the veteran is too sick to come to clinic. Programs in other nations, such as the Gold Standard Framework in the United Kingdom, use responses to the question of whether the primary care clinician would be surprised if the person died within the coming year (Royal College of General Practitioners, 2011).

Team-Based Care

Care of people with serious illness ordinarily requires an interdisciplinary team that includes some of the following: physicians, nurses, social workers, rehabilitation specialists, chaplains, home health aides, community health workers, and others. It is important to note that affected persons and their family caregivers are central members of successful care teams. Areas of expertise and skills needed for successful teams include pain and symptom management, expert communication capabilities, and assessment and remediation of the social contributors to ill health and suffering (such as food insecurity). Teams should be intentional about self-care, resilience, and learning from each other to enhance skills and improve the team’s long-term capacity to provide support to seriously ill people.

Caregiver Training

Most persons with serious illness require substantial caregiver support. High-quality serious illness care programs help people and their caregivers identify their needs, articulate their concerns and worries, and work together to develop a responsive support plan, including social resources such as food, safe housing, transportation, personal care aides, and financial support. A recent survey by AARP found that 46 percent of caregivers perform nursing tasks (e.g., wound care, tube feeding), so training and technical backup are also important (Reinhard, 2012).

Attention to Social Determinants of Health

Safely maintaining people with serious illnesses in community settings requires careful attention to social risks such as poverty, mental illness, unsafe housing, history of or current trauma, food insecurity, lack of transportation, and low literacy. Palliative or geriatric care teams conduct comprehensive assessments of these domains, work with community partners and colleagues (such as aging services, senior housing) to address them, and track needs of both the person and caregivers over time.

Communication Training and Supports

High-quality programs incorporate education to improve patient and family knowledge of disease progression, prognosis, and burdens and benefits of various treatment options. High-quality programs also strive to develop team skills in discussing a serious diagnosis and its implications, running a family meeting, leading an advance care planning discussion, and engaging in longitudinal shared decision-making.

Some programs use “case conferences” to communicate among disciplines and coordinate patient care. The method of the conference may vary, using in-person or virtual formats. This type of meeting allows each member to organize all resources of the team around patient priorities and care gaps to improve the care plan.

Goal-Based Care Plans

Effective programs work with seriously ill people and their caregivers to develop a care plan and adapt it as the condition and treatment goals evolve over time. Documented plans improve care transitions and support treatment concordance. Leveraging interoperable electronic health records and other technologies allows for timely input and retrieval of information. Successful programs incorporate longitudinal processes of advance care planning to anticipate future decline and ascertain personal values over time related to quality of life and treatment interventions.

Symptom Management

Symptom burden is high among persons living with serious illness; therefore, symptom control is a top concern. Model programs ensure that care teams are capable of recognizing and addressing pain, breathlessness, nausea, constipation, fatigue, depression, and other symptoms. Symptoms may be rooted in physical, emotional, social, or spiritual sources. Treatment options should incorporate skills from each discipline and may be pharmacologic or non-pharmacologic.

Medication Management

Assessment of medication regimens, including drug-to-drug interactions, side effects, patient adherence, and optimization of disease control are important to the safety and quality of care, as is the ability to deprescribe. Attention to affordability and access to appropriate medications through financial counseling or referrals for financial support or through price reduction programs is effective in relieving some of the

financial stress that patients and their families face.

Accessible

High-quality model programs engage in proactive outreach to target the appropriate population, and make services available when and where needed. The provision of services 24/7 with the care plan in hand is standard in quality programs.

Transitional Care

Model programs have processes in place for appropriate and informed transitions between all care settings and consistent handoffs to professionals in other settings to improve safety and adherence to a person’s preferred care plan. The capacity to recognize eligibility for hospice and to make timely referrals can improve quality of care at the end of life.

Ability to Measure Value for Accountability and Improvement

Achieving measureable and meaningful outcomes is critical for sustainable programs. Programs must be able to capture both quality and cost data about the target population in order to ensure quality and demonstrate to stakeholders and funders that the program is achieving its intended outcomes. Model care programs routinely track discrete and measureable outcomes for both quality improvement and accountability purposes. Measures may include appropriate utilization of health services, symptom burden over time, resolution of clinical care gaps, and/or improved person and family experience and satisfaction.

Model Programs

In recent years, there has been significant growth in the number of community-based serious illness care programs. Dozens of programs at various stages of development have been identified, although few encompass all of the core competencies identified above (California Health Care Foundation, 2014; CAPC, 2016). The growth of such programs continues to be driven, in part, by the health care needs of an aging population, the growing numbers of individuals with multiple complex chronic conditions or serious illness in need of comprehensive care in a cost-effective manner, and service gaps for those ineligible for hospice care or not in need of hospitalization (Bainbridge, 2010).

Recent changes in health care financing, stemming in part from the provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) (2010) have offered incentives for community-based serious illness programs to grow. Both public and private payers have embraced value-based payment programs (e.g., readmission penalties, shared savings, risk sharing, bundled payments) that encourage the development of new models of care that reward improved care quality leading to reduced cost (Discern Health, 2016; Valuck, 2017). These changes in health care payment have opened up opportunities for new model programs that serve people with serious illness residing in non-hospital settings and fill an important need for coordinated and comprehensive services (Barbour, 2012; Kamal, 2013; Morrison, 2013; Twaddle, n.d.).

Innovative models of community-based care for people with serious illness have started to demonstrate significant clinical benefits leading to reduced need for crisis services. A literature review by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER, 2016) described several model programs that have validated the benefits of palliative care outside of the inpatient care setting in terms of improved quality of life, health outcomes, and patient satisfaction. A growing number of research findings indicate that palliative care provided in community settings (as compared to inpatient settings) results in significant clinical benefits in improved symptom management, increased survival, and better caregiver outcomes (Bainbridge, 2016; Bakitas, et al., 2015; Rabow, 2013; Seow, 2014; and Temel, 2007), and some studies have demonstrated an associated reduction in costs (Brumley, 2007; Cassel, 2016). Comprehensive geriatric care models have also demonstrated lower costs and higher quality, including Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (Counsell, 2009; Hong, 2014), the Hospital at Home Program (Leff, 2005), the Independence at Home Program (CMMI, 2016) and Guided Care (Boult, 2013; Leff, 2009).

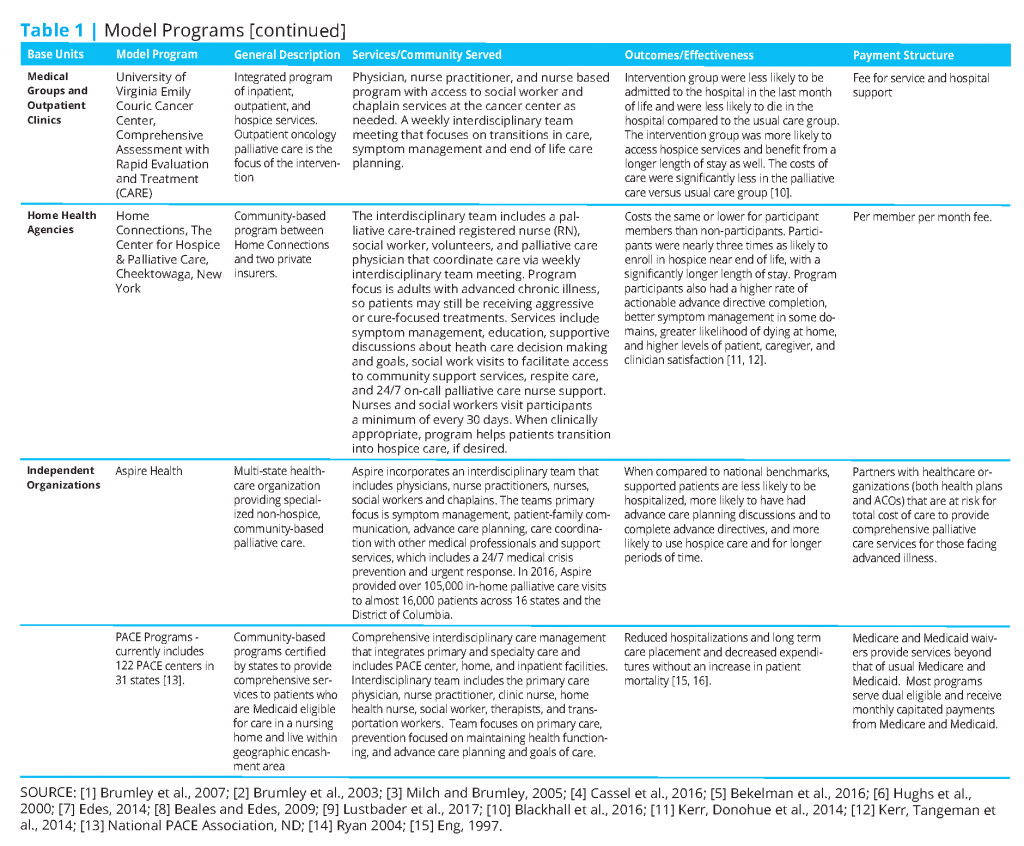

Table 1 provides examples of various models of community-based serious illness care programs. The table does not include traditional hospice programs (which provide services to persons nearing the end of life) or innovations that operate only in institutional settings (such as the INTERACT program or the Hope Hospice and Palliative Care program in Rhode Island that serves nursing home residents). These types of programs also play critical roles in caring for people with serious illness, but do not meet our definition of a comprehensive, community-based serious illness care program.

Community-based serious illness care programs have been established by many different types of organizations:

- Health Systems. A growing number of serious illness care programs operate under capitated or partial risk-bearing integrated health systems that provide coordinated and comprehensive services across settings (Beresford, 2012). Examples include Kaiser Permanente’s In-Home Palliative Care Program, the Veterans Affairs’ Team Managed Home Based Primary Care Program, Children’s National Health System’s PANDA Program and Sharp HealthCare Transitions Program.

- Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). Since the passage of the ACA, accountable care organizations have grown considerably. ACOs are not integrated health systems, but rather a group of health care provider organizations that agree to work together to reduce health care costs while maintaining quality, as well as to share in any savings. An example of a community-based serious illness care program sponsored by an ACO is ProHEALTH Care Support in Lake Success, NY.

- Medical Groups or Outpatient Clinics. Many inpatient palliative care providers have now expanded their programs into outpatient or medical group clinics. Many of these programs are associated with medical oncology practices (Hui, 2015; Partridge, 2014), for example, the Comprehensive Assessment with Rapid Evaluation and Treatment (CARE Track) program in Virginia (Blackhall, 2016).

- Home Health Agencies. Many organizations that have traditionally provided home health or hospice services are now developing comprehensive, community-based serious illness care programs, for example, Home Connections sponsored by The Center for Hospice and Palliative Care (Kerr & Donahue, 2014; Kerr & Tangemon, 2014).

- Independent Organizations. Although many community-based programs have been developed by established health care organizations, such as medical groups, hospitals, and home health and hospice agencies, there are also independent organizations entering this space. Aspire Health, headquartered in Nashville, TN, has serious illness care programs in 15 states and the District of Columbia. Numerous independent programs serve individuals dually eligible under Medicare and Medicaid as part of the Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), which provides considerable flexibility to build programs that leverage the health care and social service assets of a community (Lynn, 2016). Examples of PACE programs include Providence ElderPlace in Portland, OR, and Huron Valley PACE in Ypsilanti, MI.

Moving Forward

The growth in community-based serious illness care programs is encouraging. Some frail elders and others with serious illness and disabilities in at least some communities are beginning to have options to receive needed health care and social supports while remaining in their homes. But much work remains to be done.

Applied health services research and systems improvement are needed to guide the future development and evolution of community-based serious illness care programs. Studies of models of care need to be broadened to overcome the constraints of a limited number of comparative studies and the heterogeneity of diverse variables such as intervention targets, diseases, socio-demographics, and complex service configurations (Bainbridge, 2011; ICER, 2016; Luckett, 2014). As these programs continue to grow, there is a need for quality and cost-effectiveness analyses that define best practices across settings, patient populations, and service structures (ICER, 2016; Meyers, 2014; Morrison, 2013). Future work should also substantiate the value of community-based serious illness care programs against a backdrop of social determinants of health, regional variations, and workforce capabilities and constraints. Further, individual and family experiences of care across the various models have yet to be fully evaluated (Beattie, 2014; van der Eerden, 2014).

Payment and benefit programs must continue to evolve for serious illness care programs to thrive. Although not the focus of this discussion paper, our review of various payment programs revealed many different approaches to financing (Discern, 2016). The field would benefit greatly from a better understanding of the impact of various financing methods on access, quality, and cost of community-based serious illness care (Aldridge, 2015; ICER, 2016).

There is also an urgent need to develop a robust accountability system for community-based programs. An expert panel recently convened by Pew Charitable Trusts and others concluded that a very small number of performance measures exist to assess care for the very final stage of life—and even fewer to evaluate the care received by those struggling with serious illnesses over longer periods of time (Pew Charitable Trust, 2017). Serious illness care programs serve some of the most vulnerable populations, including frail elders, people with physical and cognitive disabilities, those with life-threatening medical diagnoses, and those nearing the end of life. Proper oversight and transparency are key to early detection and remediation of barriers to access, as well as avoiding poor-quality care, including inappropriate under-treatment, unsafe environments, and excessive out-of-pocket expenditures.

Lastly, further thought should be given to how best to ensure access to safe, high-quality care for all people in a geographic community, especially those who lack health insurance, have limited financial resources, or have no family members to serve as caregivers and advocates. There is a need to define the roles and responsibilities of health care organizations providing serious illness care to a specified patient population and social service and support organizations that serve an entire geographically-defined community. For many people, serious illness care requires a careful blend of health care and social supports. Most social services are geographically anchored in their community’s arrangements for shared resources, such as disability-adapted housing and transportation and home-delivered food; and most communities lack effective processes for planning and coordinating the social services provided by community agencies with the care provided by a myriad of different health care organizations. Adequately serving the entire population of people with serious illness in a geographic area will require broader community planning and engagement.

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- Aldridge, M. D., and A. S. Kelley. 2015. The myth regarding the high cost of end-of-life care. American Journal of Public Health 105(12):2411-3415. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302889

- Bainbridge, D., H. Seow, and J. Sussman. 2016. Common components of efficacious in-home end-of-life care programs: A review of systematic reviews. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 64(3):632-639. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14025

- Bainbridge, D., K. Brazil, P. Krueger, J. Ploeg, and A. Taniguchi. 2010. A proposed systems approach to the evaluation of integrated palliative care. BMC Palliative Care 9: 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-9-8

- Bakitas, M. A., T. D. Tosteson, Z. Li, K. D. Lyons, J. G. Hull, Z. Li, J. N. Dionne-Odom, J. Frost, K. H. Dragnev, M. T. Hegel, A. Azuero, and T. A. Ahles. 2015. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 33(13):1438-1445. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362

- Barbour, L. T., S. E. Cohen, V. Jackson, E. Kvale, C. Luhrs, V.D. Nguyen, M.W. Rabow, S. Rinaldi, L.H. Spragens, D. Stevens, and D.E. Weissman. 2012. Models for palliative care outside the hospital setting. A Technical Assistance Monograph from the IPAL-OP Project, Center to Advance Palliative Care. Available at: http://ipal.capc.org/downloads/overview-of-outpatient-palliative-caremodels.pdf (accessed February, 2016).

- Beales, J. L., and T. Edes. 2009. Veteran’s Affairs Home-Based Primary Care. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 25(1):149-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2008.11.002

- Beattie, M., W. Lauder, I. Atherton, and D. J. Murphy. 2014. Instruments to measure patient experience of health care quality in hospitals: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews 3:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-4

- Bekelman, D. B., B. A. Rabin, C. T. Nowels, A. Sahay, P. A. Heidenreich, S. M. Fischer, and D. S. Main. 2016. Barriers and facilitators to scaling up outpatient palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine 19(4):456-459. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0280

- Beresford, L. and K. Kerr. 2012. Next generation of palliative care: Community models offer services outside the hospital. California Health Care Foundation. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/PDF%20N/PDF%20NextGenerationPalliativeCare.pdf. (Accessed April 5, 2017)

- Blackhall, L. J., P. Read, G. Stukenborg, P. Dillon, J. Barclay, A. Romano, and J. Harrison. 2016. CARE track for advanced cancer: Impact and timing of an outpatient palliative care clinic. Journal of Palliative Medicine 19(1):57-63. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0272

- Boult, C., B. Leff, C. M. Boyd, J. L. Wolff, J. A. Marsteller, K. D. Frick, S. Wegener, L. Reider, K. Frey, T. M. Mroz, L. Karm, and D. O. Sharfstein. 2013. A matched-pair cluster-randomized trial of guided care for high risk older patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine 28(5):612-621. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2287-y

- Brumley, R., S. Enguidanos, P. Jamison, E. Seitz, N. Morgenstern, S. Saito, J. McIlwane, K. Hillary, and J. Gonzalez. 2007. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in home palliative care. Journal of American Geriatrics Society 55:993-1000. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x

- Brumley, R., S. Enguidanos, and D. Cherin. 2003. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. Journal of Palliative Medicine 6:715-724. https://doi.org/10.1089/109662103322515220

- California Health Care Foundation. 2017. Up close: A field guide to community-based palliative care in California. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/publications/2014/09/up-close-field-guide-palliative (accessed April 5, 2017).

- Cambia Health Foundation. 2011. NEW POLL: Americans choose quality over quantity at the end of life, crave deeper public discussion of care options. Available at: http://www.cambiahealthfoundation.org/media/release/07062011njeol.html (accessed April 5, 2017).

- Cassel, B. J., K. M. Kerr, D. K. McClish, N. Skoro, S. Johnson, C. Wanke, and D. Hoefer. 2016. Effect of a home-based palliative care program on healthcare use and costs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 64(11):2228-2295. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14354

- CAPC (Center to Advance Palliative Care). 2016. Palliative care in the home: a guide to program design. Available at: https://www.capc.org/shop/catalogue/palliativecare-in-the-home-a-guide-to-program-design_3/ (accessed April 5, 2017).

- Counsell, S. R., C. M. Callahan, W. Tu, T. E. Stump, and G. W. Arling. 2009. Cost analysis of the geriatric resources for assessment and care of elders care management intervention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57(8):1420-1426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02383.x

- Discern Health. 2016. Payment models for advancing serious illness care. Available at: http://discernhealth.com/wpcontent/uploads/2017/01/Moore-Serious-IllnessCare-Payment-Models-White-Paper-2016-09-27.pdf (accessed April 5, 2017).

- Edes, T. B., N. H. Vuckovic, L. O. Nichols, M. M. Becker, and M. Hossain. 2014. Better access, quality, and cost for clinically complex veterans with home-based primary care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 62(10):1954-1961. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13030

- Eng, C., J. Pedulla, G.P. Eleazer, R. McCann, and N. Fox. 1997. Program of All‐inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE): an innovative model of integrated geriatric care and financing. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 45(2), 223-232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04513.x

- Hong, C. S., A. L. Siegel, and T. G. Ferris. 2014. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: What makes for a successful care management program? Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2014/aug/high-need-high-cost-patients (accessed March 9, 2017).

- Hui, D., Y. J. Kim, J. C. Park, Y. Zhang, F. Strasser, N. Cherny, S. Kaasa, M. P. Davis, and E. Bruera. 2015. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A systematic review. Oncologist 20:77-83. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0312

- Hughs, S. L., F. M. Weaver, A. Giobbie-Hurder, W. Henderson, J. D. Kubal, A. Ulasevich, and J. Cummings. 2000. Effectiveness of team-managed home-based primary care—a randomized multicenter trial. JAMA 284:2877-2885. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.22.2877

- ICER (Institute for Clinical and Economic Review). 2016. Palliative care in the outpatient setting. Available at: http://icer-review.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/04/NECEPAC_Palliative_Care_Final_Report_042716-1.pdf (accessed April 5, 2017).

- Institute of Medicine. 2015. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18748

- Kamal, A. H., D. C. Currow, C. S. Ritchie, J. Bull, and A. P. Abernethy. 2013. Community-based palliative care: The natural evolution for palliative care delivery in the U.S. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 46(2):254-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.07.018

- Kelley, A. S., K. Covinsky, R. J. Gorges, K. McKendrick, E. Bollens-Lund, R. S. Morrison, and C. S. Ritchie. 2017. Identifying older adults with serious illness: A critical step toward improving value of health care. Health Services Research 52(1):113-131. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12479

- Kerr, C. W., K. S. Donohue, J. C. Tangeman, A. M. Serehali, S. M. Knodel, P. C. Grant, D. L. Luczkiewicz, L. Mylotte L, and M. J. Marien. 2014. Cost savings and enhanced hospice enrollment with a home based palliative care program implemented as a hospice-private payer partnership. Journal of Palliative Medicine 17:1328-1335. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.0184

- Kerr, C. W., J. C. Tangeman, C. B. Rudra, P. C. Grant, D. L. Luczkiewicz, K. M. Mylotte, W. D. Riemer, M. J. Marien, and A. M. Serehali. 2014. Clinical impact of a home-based palliative care program: A hospice-private payer partnership. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 48(5):883-892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.02.003

- Leff, B., L. Burton, S. L. Mader, B. Naughton, J. Burl, S. K. Inouye, W. B. Greenough, S. Guido, C. Langston, K. D. Frick, D. Steinwaches, and J. R. Burton. 2005. Hospital to home: Feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Annals of Internal Medicine 143(11):798-808. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-143-11-200512060-00008

- Leff, B., L. Reider, K. D. Frick, D. O. Scharstein, C. M. Boyd, K. Frey, L. Karm, and C. Boult. 2009. Guided care and the cost of complex healthcare: A preliminary report. American Journal of Managed Care 15(8):555-559. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19670959/ (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Luckett, T., J. Phillips, M. Agar, C. Virdun, A. Green, and P. M. Davidson . 2014. Elements of effective palliative care models: A rapid review. BMC Health Services Research 14:136. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-136

- Lustbader, D., M. Mudra, C. Romano, E. Lukoski, A. Chang, J. Mittelberger, T. Scherr, and D. Cooper. 2017. The impact of a home-based palliative care program in an accountable care organization. Journal of Palliative Medicine 20(1):23-28. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0265

- Lynn, J. 2016. MediCaring Communities: Getting what we want and need in frail old age at an affordable cost. Ann Arbor, MI: Altarum Institute.

- Meier, D. E., and E. McCormick. Benefits, services, and models of subspecialty palliative care. UpToDate®. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/benefits-services-and-models-of-subspecialty-palliative-care (accessed December 1, 2016).

- Meyers, K., K. Kerr, and J. B. Cassel. 2014. Up close: A field guide to community-based palliative care in California. Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation. Available at: https://www.chcf.org/publication/up-close-a-field-guide-to-community-based-palliative-care-in-california/ (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Milch, M., and R. D. Brumley. 2005. A quarter century of hospice care: The southern California Kaiser Permanente experience. The Permanente Journal 9(3):28-31. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/04-060

- Morrison, R. S. 2013 Models of palliative care delivery in the United States. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care 7(2):201-206. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0b013e32836103e5

- NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/23606

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. 2013. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. Third edition. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Palliative Care. National PACE Association. Facts and trends. Available at: http://www.npaonline.org/policy-and-advocacy/pacefacts-and-trends-0 (accessed April 5, 2017).

- NIA (National Institute on Aging). 2011. Global health and aging. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- NQF (National Quality Forum). Palliative and end-of-life care 2015-2016: Technical report. 2016. Washington DC: National Quality Forum. Available at: https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2016/12/Palliative_and_End-of-Life_Care_2015-2016.aspx (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Partridge, A. H., D. S. Seah, T. King, N. B. Leighl, R. Hauke, D. S. Wollins, and J. H. Von Roenn. 2014. Developing a service model that integrates palliative care throughout cancer care: The time is now. Journal of Clinical Oncology 32:3330-3306. Available at: https://www.slaop.org/pdf/711PaliativoDevelopingaServiceModelThatIntegratesPalliativeCareThroughoutCancerCareTheTimeIsNow.pdf (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Pew Charitable Trusts. 2017. Building additional serious illness measures into medicare programs. Washington DC: Pew Charitable Trusts. Available at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/about/news-room/opinion/2017/05/25/building-additional-serious-illness-measures-into-medicare-programs (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Rabow, M., E. Kvale, L. Barbour, J. B. Cassel, S. Cohen, V. Jackson, C. Luhrs, V. Nguyen, S. Rinaldi, D. Stevens, L. Spragens, and D. Weissman. 2013. Moving upstream: A review of the evidence of the impact of outpatient palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine 12:1540-1549. Available at: https://connects.catalyst.harvard.edu/Profiles/display/28384950 (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Reinhard, S., C. Levine, and S. Samis. 2012. Home alone: Family caregivers providing complex chronic care. Washington DC: AARP. Available at: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/health/home-alone-family-caregivers-providing-complex-chronic-care-rev-AARP-ppi-health.pdf (accessed August 24, 2020).

- Royal College of General Practitioners. 2011. The Gold Standard Framework: The GSF Prognostic Indicator Guidance. Available at: http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/General%20Files/Prognostic%20Indicator%20Guidance%20October%202011.pdf. (Accessed April 5, 2017).

- Ryan, S. D., M. Tuuk, and M. Lee. 2004. PACE and hospice: two models of palliative care on the verge of collaboration. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 20(4), 783-794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2004.07.012

- Seow, H., K. Brazil, J. Sussman, J. Pereira, D. Marshall, P. C. Austin, A. Husain, J. Rangrej, and L. Barbera. 2014. Impact of community-based, specialist palliative care teams on hospitalisations and emergency department visits late in life and hospital deaths: a pooled analysis. BMJ 348(g2496):1-10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3496

- Temel, J. S., V. A. Jackson, J. A. Billings, C. Dhalin, S. D. Block, M. K. Buss, P. Ostler, P. Fidias, A. Muzikansky, J. A. Greer, W. F. Pirl, and T. J. Lynch TJ. 2007. Phase II Study: integrated palliative care in newly diagnosed advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology 25(17):2377-2382. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2627

- Teno, J. M., P. L. Gozalo, J. P. W. Bynum, N. E. Leland, S. C. Miller, N. E. Morden, T. Scupp, D. C. Goodman, and V. Mor. 2013. Change in end-of-life care for medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA 309(5):470-477. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.207624

- Twaddle, M. L., and E. McCormick. 2016. Palliative care delivery in the home. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/palliative-care-delivery-in-the-home (accessed December 1, 2016).

- Valuck, T., and R. Montgomery. 2017. Innovation in serious illness care payment: Progress to date and opportunities for the new administration. Health Affairs Blog. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2017/03/08/innovation-in-serious-illness-care-payment-progress-todate-and-opportunities-for-the-new-administration(accessed April 5, 2017).

- van der Eerden, M., A. Csikos, B. Busa, S. Hughes, L. Radbruch, J. Menten, J. Hasselaar, and M. Groot. 2014. Experiences of patients, family and professional caregivers with Integrated Palliative Care in Europe: Protocol for an international, multicenter, prospective, mixed method study. BMC Palliative Care 13:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-13-52

Aging, Chronic Disease, Coverage and Access, Health Policy and Regulation, Longevity, Prevention