Case Study: Improving Population and Individual Health Through Health System Transformation in Washington State

“It is a very exciting time in Washington. I see us as a state moving forward with approaches that will change the health status of our citizens.”

MaryAnne Lindeblad, BSN, MPH, Medicaid Director, Washington State Health Care Authority

Empowered by federal, state, and community funding, Washington State has been working for years to enact delivery system transformation to improve the health and well-being of its 7 million residents. In fact, in the 1990s Washington State passed legislation offering universal coverage for its residents. But when the individual mandate was repealed just a year after implementation, insurance premiums spiked, and many plans left the state. Then-governor Chris Gregoire shared her state’s lessons with President Barack Obama during his presidential campaign, advising that universal coverage without an individual mandate is a recipe for failure. When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was signed into law in 2010 with an individual mandate, Washington was already well poised for implementation, having attempted, and learned from, its previous universal coverage experiment.

The health system transformation effort in Washington has evolved since the 1990s and now takes a multipronged approach, especially in the Medicaid program, using a variety of health system improvement strategies. Some initiatives are broad, creating cross-sector collaborations among Medicaid, providers, public health, and community-based organizations in order to advance population health goals. Others are more targeted, providing preventive services to individual Medicaid enrollees in nontraditional ways.

This case study will highlight the innovative range of options available through Apple Health, Washington’s Medicaid program, to provide upstream and population-level health improvement to its residents statewide. To do so, this paper provides a brief history of Washington State’s health system transformation and the context in which its upstream and population health strategies were developed, as well as an analysis of the accelerators of, and barriers to, success, concluding with a review of lessons learned. It is important to note that while obesity prevention is a major priority for current Governor Jay Inslee, and the Healthier Washington framework includes obesity prevention as a focus area, the initial programs and services described below apply to health improvement more generally, with the expectation that they will be expanded and applied to childhood obesity in the future.

Overview of Healthier Washington: Improving Services And Payment To Achieve Improved Health

Leveraging Federal Funds to Transform How Care Is Delivered

With Governor Inslee’s support, Washington State applied for, and was one of three states awarded a $1 million, 6-month state innovation model (SIM) pretesting award from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) in April 2013. The SIM award supported the planning and development of a 5-year state health care innovation plan to serve as the framework for health system transformation within the state. The resulting innovation plan, now called Healthier Washington, received an additional $65 million in the form of a 4-year SIM award as part of a round two model test grant from CMMI in late 2014 for capacity building and testing.

Healthier Washington is a multipayer, integrated care model designed to improve individual and population health throughout Washington. Its main goals—improving care coordination, population health, and health care delivery payment—called for a fundamental change to the way health and health care was viewed and delivered in the state. Rather than taking a top-down approach, with health care decisions made and mandated by the Health Care Authority (HCA), the agency that purchases health care for Apple Health, Healthier Washington takes a bottom-up approach, allowing regional community health needs to influence which services are delivered and how. Healthier Washington Target areas are described below.

Healthier Washington Target Areas:

- Empowering communities and ensuring accountability: Using accountable communities of health (ACHs) to spur local population health innovation and holding those ACHs accountable for performance results and improvements.

- Practice transformation: Encouraging provider behavior change through practice transformation coaching that supports transitions to value-based, integrated care.

- Shifting to value-based purchasing: Using several health delivery models that support purchasing high-value care, engaging the purchasers, reducing provider fatigue, ensuring state Medicaid per-capita cost growth comes in below national trends, and reducing the use of avoidable high-cost services (e.g., psychiatric hospitals, nursing homes, acute care hospitals) through preventive efforts, when possible.

- Monitoring and reporting: Investing in the development of measures and tools needed to analyze, interpret, and translate data into action.

- Project management: Supporting public-private leadership, interagency partnerships, and legislative oversight, all of which are accountable for continuous improvement of Healthier Washington initiatives.

As part of Healthier Washington, the state applied for and recently received approval for a 5-year section 1115 Medicaid project demonstration to focus specifically on transforming the care received by the 25 percent of Washington’s population who are on Medicaid. The transformation demonstration initiatives are designed to complement and accelerate, not compete with, the work being done through the SIM grant, and in some instances, overlap directly. For example, the demonstration includes a delivery system reform incentive payment program that calls for practice transformation through the ACHs, which are cross-sector partnerships established to address the health needs of the population within a designated region.

Improving Population Health from the Bottom Up

“Health care is local, and local communities must be empowered to identify their own needs, goals, and solutions.” – MaryAnne Lineblad discussing the significance of Washington’s accountable communities of health

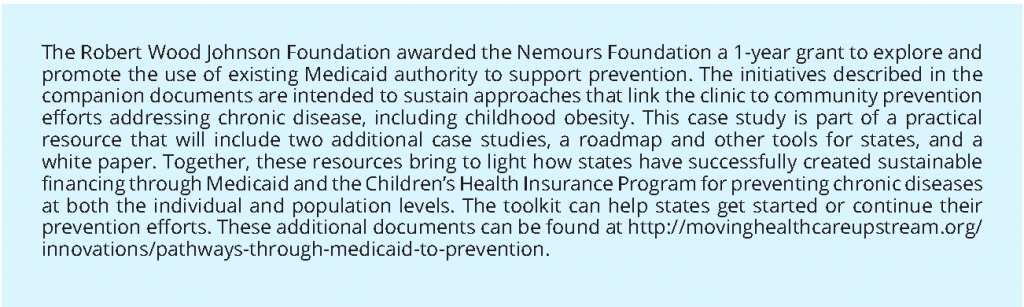

Central to Washington State’s delivery system transformation effort are ACHs. Washington has nine ACHs across the state (see map in Figure 1). ACHs serve as integrators, which are individuals or entities that work intentionally and systematically across sectors (e.g., health, public health) to achieve improvements in health and well-being. ACHs align regional activities and statewide plans to address the social determinants of health, provide high-value health care, and promote greater population health in their geographic areas. To receive official designation by the state, each ACH had to develop a regional health needs inventory and establish a region-specific improvement plan. Through the inventory process, the ACHs have been able to identify priority areas specific to their region (e.g., social determinants of health, physical–behavioral health integration, care coordination) and consequently design improvement initiatives that can be implemented locally to address those priority areas. With support from the HCA the identified health improvement initiatives within each region can then be implemented.

The first two pilot ACHs were funded in 2015 with $150,000 in state appropriations made to the HCA. Later that year, a 1-year SIM award of $100,000 funded seven more ACHs (Center for Community Health and Evaluation, 2016). Moving forward, much of the funding for all nine ACHs—$810,000 to be distributed between 2016 and 2019 (Center for Community Health and Evaluation, 2016; Heider et al., 2016)—will come from the delivery system reform incentive payment program, part of the transformation demonstration that provides funding to help change how care is delivered to Medicaid beneficiaries, as measured through the achievement of project-related milestones (Gates et al., 2014). As part of the delivery system reform incentive payment program, ACHs are guided by a community framework that sets the focus areas under which regional projects can be funded. These focus areas are health systems capacity building, care delivery redesign, and prevention and health promotion. Proposed regional projects must be approved by HCA, pertain to one of the three focus areas, and demonstrate a 5-year return on investment. Program performance evaluations are completed by the ACH and, if milestones are met, ACHs will maintain the authority to decide how to reinvest their shared savings. (See the “Accelerators” section of this case study for more information about ACH and MCO incentives for achieving value-based payment goals.)

Washington’s Transformation Demonstration Enables Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) to Work Upstream to Address the Social Determinants of Health

Expansion of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), followed by passage of the ACA under President Obama, ensured that more people than ever would receive health care through Medicaid. Yet, as more people were eligible for coverage, the Great Recession in the late 2000s created a need for Washington State to cut back on health care spending, resulting in a focus on prevention and the reduction of high-cost treatments and services. The Health in all Policies guide released in 2013 offered implementable steps to improve the health of Medicaid enrollees by addressing the non-medical upstream contributors to health (housing, unemployment, food insecurity) and helped shape incoming Governor Inslee’s health care agenda (Rudolph et al., 2013). Healthier Washington ensures that these nonmedical social determinants of health are addressed as a means to (1) improve health for all Washingtonians, and (2) to combat rising health care costs.

MCOs in Washington State provide health care services to residents through the same regional approach as ACHs, making it easy for ACHs to align their services with the needs of their community. (For more details about the relationship between Washington’s MCOs and ACHs, refer to the “Accelerators” section of this case study.) At the individual Medicaid enrollee level, the transformation project will reimburse MCOs for foundational community supports for eligible enrollees with demonstrated medical or functional needs. For housing-related supports this would not include paying an enrollee’s rent or mortgage, but it would cover the costs related to finding and obtaining housing, resolving landlord disputes and other housing-related advocacy issues, and linking program participants to other community resources. And for eligible Medicaid enrollees with physical, behavioral, or other long-term service needs who may otherwise have trouble maintaining employment, these supports would also include employment assistance services (e.g., job coaching and training, job placement assistance). Because housing instability and unemployment are often linked to poor health outcomes, preventing homelessness and joblessness is expected to lead to better health for program participants and therefore lower the health care costs related to treating those individuals.

Leveraging Medicaid Authorities—Maximizing Use of Flexibility to Improve Whole-Person Health

MCOs have a great deal of flexibility in how they deliver preventive services. They can reimburse for nontraditional care delivered by nontraditional providers, such as community health workers, in such nontraditional settings as the home or school, or they can reimburse for nontraditional upstream services, such as lead abatement, for both Medicaid enrollees and the population as a whole. The decision about how to use that flexibility rests with the MCO, rather than with the state Medicaid agency. Though the political environment in the country is changing, MCOs maintain their extensive flexibility under current Medicaid and CHIP authority to implement prevention interventions. (For more information about how states can maximize the authority that exists under federal Medicaid and CHIP law to deliver a range of preventive health services, please see “Roadmap of Medicaid Preventive Pathways,” which accompanies this case study.) Therefore, the fact that 88 percent of Washington’s Medicaid population is covered by an MCO means that the majority of Medicaid enrollees in Washington can benefit from innovative health care delivery (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016).

For example, through a state plan amendment in 2013, Washington applied for and received approval to implement Medicaid health homes with a provision allowing some services to be provided by non-traditional providers, such as community health workers. Paid by the state on a per member, per month basis, health homes exist to address complex health issues for Medicaid enrollees who suffer from at least one chronic condition and who are at risk for a second. Eligible provider settings include traditional settings such as hospitals, federally qualified health centers, and MCOs, as well as nontraditional settings such as community health and mental health centers. Among other things, services offered by health homes include referrals to community and social services, transition of inpatient care to other settings, and general health promotion and care coordination activities. Community health workers participating in health homes provide administrative support for the health home coordinator, such as mailing promotional material, arranging for transportation, and facilitating face-to-face visits with the care coordinator. In addition, a community health worker task force recently made recommendations to the state about ways to expand the role of community health workers in health homes and other health-related programs in the coming years.

Governor Inslee launched the Healthiest Next Generation initiative, aimed specifically at ensuring that children in Washington are able to maintain healthy weights through an emphasis on healthy eating and physical activity programs. Though not Medicaid funded as a whole, Healthiest Next Generation is supported in part by federal match rates for Medicaid administrative activities, and it also includes Medicaid reimbursement for certain community-level population health projects. One example, Breastfeeding Friendly Washington, works to ensure that Medicaid reimburses for, and communities have the resources needed to provide, breastfeeding and lactation education and counseling throughout a variety of traditional and non-traditional settings, including worksites and early learning centers. Since breastfeeding is linked to improved maternal and infant outcomes overall, and obesity rates are significantly lower in breastfed infants compared to nonbreastfed infants (AAP, 2012), this program contributes to healthy child development and a reduction in childhood obesity.

Factors That Affect Health System Transformation at The State Level

In a state as large and diverse as Washington, health system transformation requires substantial planning, coordination, and resources. The following section describes “accelerators,” or specific actions that contribute to Washington’s transformation. Many of these accelerators are related to the ACHs and the role they play at the regional level.

Accelerators

Washington Got an Early Start and Has a Strong Base from Which to Build

Washington State was uniquely positioned to make strides toward achieving the triple aim—improving care, improving population health, and reducing costs (Berwick et al., 2008)—for its residents in part because the ACA’s Basic Health Program, a program that provides low-income residents with coverage, is based on Washington’s own basic health plan (BHP), which was implemented in the late 1980s.

With a population focus and infrastructure already in place, Washington State was one of seven states able to prepare to expand Medicaid early under the ACA, surpassing its 2018 enrollment goal by 2014 (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016). The majority of Washington’s BHP members were transitioned to Medicaid through the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, and as a result, the BHP was ended. Additionally, owing to the ease of transition from the BHP to Medicaid, the state is further along in its delivery system transformation process than states that enacted the transformation later, and those that opted not to expand their Medicaid programs at all, and Washington State is reaching more residents than originally expected at this point.

Collaborative Planning Process Ensured Buy-In from the Start that Continues Today

Providing care to low-income residents remains a priority to health care and government leaders throughout the state. And, after living through the initial failure of the state’s universal health care attempts in the 1990s and offering insight into the formulation of the ACA based on lessons learned in Washington State, former Governor Gregoire saw another opportunity to expand and reform the way health care was delivered to residents of her state. To prepare for implementation of the ACA, Governor Gregoire convened an advisory workgroup on health care reform to draft actionable recommendations for health care reform.

After taking office in early 2013, Governor Inslee continued former Governor Gregoire’s charge for statewide reform by implementing the ACA Medicaid expansion in Washington State and supporting and signing his name to the state transformation project, which incorporated many of the recommendations from the advisory workgroup on health care reform. He also worked to drum up bipartisan support in the state legislature for bills that support health care delivery for the “whole person” and the purchase of health care that emphasizes quality and transparency.

The governor placed oversight of Healthier Washington under HCA’s purview. HCA works with the Department of Health and Department of Social and Health Services for leadership and implementation. Further, several other state agencies work with HCA to provide governance. According to MaryAnne Lindeblad, Medicaid director of the HCA, these agencies have a very “tight knit” relationship and have for some time, a factor which no doubt eased the facilitation of Healthier Washington [1].

ACH Contracts Require Alignment of Clinic and Community Resources and Goals

The creation of the ACHs drives system transformation to address the local and regional needs of residents, offering flexibility in how care is delivered. ACHs, serving as integrators, foster collaboration by gathering input from community members and leaders to determine regional needs, communicating those needs to the MCOs who must then work with the HCA and each other to translate their members’ needs into action.

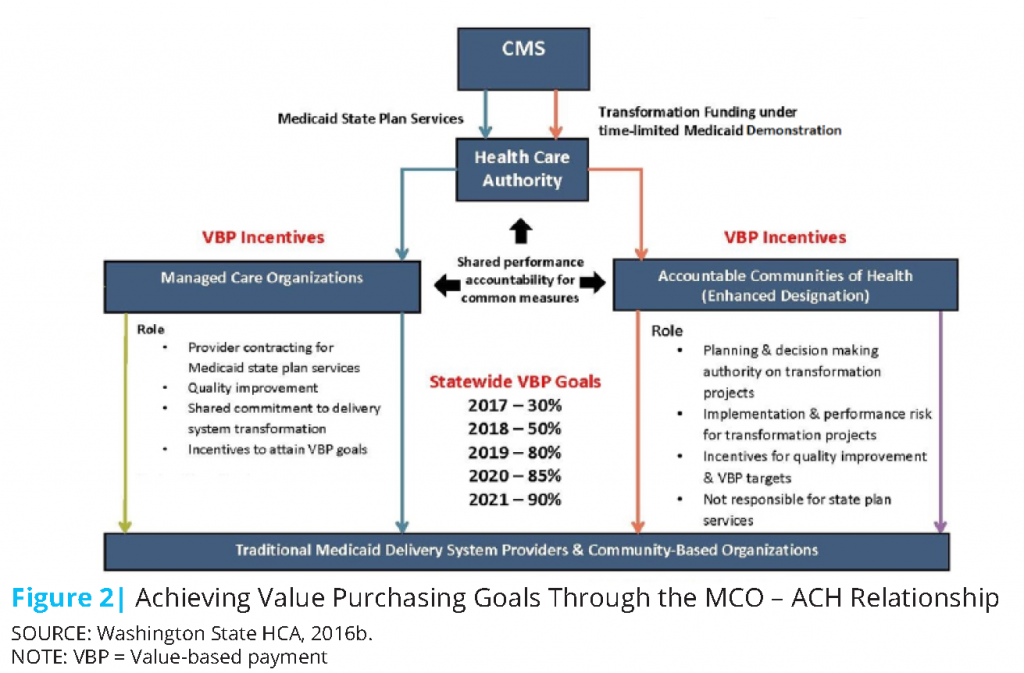

In creating the structure and processes necessary to bring sectors together to share information and make decisions, Washington works to ensure that all needs, not just the health-specific needs, of its residents are addressed. The ACHs were designed specifically and deliberately to work locally with residents, providers, social services, and community-based organizations to determine the regional community needs and collaboratively take action to address those needs. The MCOs, which are ACH participants, are then able to provide treatment and services, including addressing the nonmedical social determinants of health, specific to the needs in those regions. Though ACHs are not risk-bearing entities like MCOs, their partnership with MCOs ensures they have influence over the decisions made about the purchase and delivery of health care in their regions. With regard to the Medicaid transformation demonstration, ACHs also work directly with the HCA and decide which transformation projects to fund. They work with one another to ensure data and lessons learned are shared between regions. The relationship between the MCOs and ACHs to achieve the demonstration’s value-based purchasing goals can be seen in Figure 2.

In addition, the general makeup of the governing bodies of each ACH must contain a balance of representatives from health care agencies (no more than 50 percent can be from Medicaid managed care, hospitals, and health systems) and organizations that work in the social determinants of health arena (CRHN, 2016). To be balanced, capable of making informed decisions, and representative of the needs of the region, each ACH is required, at a minimum, to address issues affecting the following sectors: financial, clinical, community, data, and program management. The structure of these governing bodies varies from ACH to ACH, and more diverse or populated regions may require membership from additional domains (CRHN, 2016).

Emphasis on Data Collection and Sharing Creates a System of Accountability

Standardization of measurement and data collection across regions, payers, and sectors creates a system of accountability and helps create the evidence base needed to advocate for upstream and population-level changes whose effectiveness may have otherwise been difficult to demonstrate. The Healthier Washington aim of value-based purchasing, where 90 percent of state-financed health care will be value-based by 2021, and the delivery system reform incentive payment requirements to demonstrate outcomes were major drivers in the development of standard core measures and the linkage of data repositories across the state. These core measures are population-level prevention measures such as prevalence of flu vaccinations, unintended pregnancies, smokers, and poor mental health (Washington State HCA, 2014). Such core measures are used by Medicaid, public health, and private insurers to ensure consistency of data collection across sectors, and consistency in data collection helps ensure that outcomes can be accurately assessed and linked to medical payments.

Value-Based Payment Can Be Achieved through Incentives

One of Healthier Washington’s main goals is the achievement of 90 percent value-based payment in state-financed health care by 2021. The HCA developed a value-based road map outlining steps to achieve this goal, beginning in 2017 and lasting the duration of the transformation demonstration (Washington State HCA, 2016b). One approach to achieving this goal is to incentivize MCOs with additional funds if they surpass value-based payment targets.

Both MCOs and ACHs will each have authority to incentivize providers in their networks or regions. For MCOs this will entail setting aside at least 0.75 percent of their premium as provider incentives for achieving value-based care targets. Under the demonstration, ACHs will also be able to make payments (which will vary from region to region) to participating providers for achieving designated targets.

All MCOs in Washington will also be subject to a 1 percent withholding of their premium. They will be able to earn back their withholdings through the achievement of seven performance-based measures in 2017, three of which are pediatric-specific (asthma, immunizations, and well-child visits). Additional measures and an increasing withholding (capping at 3 percent in 2021) will be added throughout the course of the demonstration period. If an MCO does not meet its performance measures, it will be required to develop a performance improvement plan outlining the steps it will take to achieve the measure in the future.

Through the demonstration, HCA has additionally established challenge pools and reinvestment pools. Through the challenge pool, MCOs are able to earn a portion of any unearned or uncollected incentives or withholdings from the overall MCO pool for exceptional performance, as judged by meeting and exceeding core quality measures. Similar to the challenge pool, the reinvestment pool awards unearned and uncollected ACH incentives and a portion of MCO incentives toward regional reinvestment projects.

Barriers

“Integrating delivery systems at the local level, engaging public health, engaging health care providers, engaging the schools, addressing housing and unemployment issues, transportation issues, food insecurity…there are multiple factors. How do you address all of these factors and bring the multiple sectors to the table?” – MaryAnne Lindeblad

Despite the aforementioned accelerators driving progress, even states as innovative as Washington face a number of barriers when attempting to transform such a complex system. Some of the barriers to realizing health system transformation at the state level are described below. It is important to point out that many of these barriers exist because of the nature of Washington’s health system transformation, and many will likely be resolved over time as they are better understood.

Prioritization of Programs That Are Easy to Measure and Evaluate

While requiring data collection and measurement is an important accelerator to health system transformation, this reliance on defined metrics and measures may limit what is currently possible under the existing grants. Since delivery system reform incentive payment funding of the ACHs, a core component of Healthier Washington, is dependent on achievement of project-specific processes and outcomes, programs with easier-to-demonstrate performance measures or cost-effectiveness may be pursued over longer-term programs that could potentially benefit more residents. Therefore, it will be important for longer-term or more complex projects to incorporate smaller, more achievable milestones throughout their planning and implementation phases so they are more likely to be funded. Finding a balance between what can be measured and improving the long-term health of residents will be essential.

Encouraging Interagency and Cross-Sector Collaboration Can Be Challenging

Collaboration among long-established agencies or existing and newly created organizations often results in some resistance from at least one organization, if not all involved. It can be difficult and time-consuming to evaluate old policies and procedures, and arduous to create new ones that reflect the priorities of more than one group. Yet one major goal of Healthier Washington, improving the health of the whole person—with specific mention of mental health and substance abuse-related coverage—presents such a challenge. Through Healthier Washington, physical and behavioral health systems throughout the state, which have existed independently, must be fully integrated by 2020. This is a major undertaking and, while it will result in better care for residents if successful, the process will likely encounter bumps along the way as previously siloed agencies are forced to form partnerships to identify and work toward shared goals.

In addition, ACHs, which are relatively new entities in the state, are still attempting to determine their role. As reported in the Center for Community Health and Evaluation’s evaluation of Washington’s ACHs released in early 2016, most of the state’s nine ACHs expressed some frustration with the HCA. Many indicated that they needed more guidance in order to work efficiently (Center for Community Health and Evaluation, 2016). At the same time, they want to be seen as partners with HCA to avoid having requirements imposed on them or timelines abruptly changed without input.

Amount of Time and Resources Needed to Conduct Regional Health Assessments

Understanding regional health needs is paramount to the establishment of ACHs. Yet prior to the transformation project, Washington had never taken a regional approach to health, and therefore the infrastructure to monitor and assess it simply did not exist. Though many counties and community agencies collect data on local health needs or conduct health needs assessments, there was no standardization of data collection methodologies, or even timeframes over which health was assessed. Though this was a necessary challenge, it became clear to many ACHs that they would be unable to rely solely on existing health data, and would instead need to reach out locally to fill in the gaps (Center for Community Health and Evaluation, 2016). However, the process to update the assessments going forward will require far fewer resources now that the infrastructure to collect and assess regional health needs has been created.

Evidence Base to Support Pursuing Upstream and Population Health Initiatives Is Limited, But Growing

Upstream and population health initiatives can be difficult to initiate without an evidence base explaining why they are worth the long-term investment. Unfortunately, data on the effectiveness of these programs are few. Since data collection and dissemination are major foci of Healthier Washington, the hope is that, in a few years, this evidence base will exist and upstream and population-level programs will be easier to defend.

Long-Term Sustainability Remains a Question

It remains unclear how these programs will continue in the absence of external funding. Seven out of nine ACHs are funded by the SIM grant, with those funds mainly devoted to initial ACH development and governance. The implementation of a multisector incentive platform, with options for incentivizing MCOs, ACHs, and providers, starting in 2017 under the demonstration begins the process for ensuring accountability for achieving value-based payments at all levels. Still, there are not yet plans to continue this incentive structure after the conclusion of the transformation demonstration. And, while a requirement of ACH designation was the development of a sustainability pathway, that pathway varies drastically among ACHs, and most rely heavily on seeking additional grants and donations, or charging members for services (Center for Community Health and Evaluation, 2016).

Lessons Learned

Since few states have achieved the level of success Washington has so far reached, many of the lessons learned about health system transformation have come through Washington’s own trial and error. The lessons described below may serve to guide other similar states through the murky process, as well as inform the planning processes of states that are just beginning their transformation.

State Leaders Need to Prioritize Upstream and Population Health and Set Clear, Achievable Goals

Washington State’s shift toward value-based care with a focus on upstream and population health starts at the top, with the governor. Governor Inslee strongly supports this effort, signing his name to the application for the implementation phase of Healthier Washington in 2014. With his support, the state enacted two bipartisan bills—HB 2572 and SB 6312—in 2014. These bills together worked to enable health system transformation through:

- the creation and funding of two pilot ACHs,

- establishing a performance measurement committee to make recommendations about statewide measures of health performance to help ensure quality of care,

- reducing extraneous health care costs by restructuring Medicaid procurement mechanisms,

- establishing an all-payer claims database through which all public purchasers in the state would need to submit claims, and

- specifying that 90 percent of behavioral and physical health services will be provided through a fully integrated managed care system by 2020.

States Should Encourage or Require Interagency Collaboration

Collaboration has been vital to the implementation of Healthier Washington. It is no easy feat to align the goals and priorities of health care, mental health, and other social services at the local, regional, and state level. An important facilitator behind those collaborative efforts has been the support and buy-in from the governor and the bipartisan support of legislators. Moreover, the leadership of every agency involved has contributed to the current successes of the initiative. As an example, the HCA is the entity responsible for purchasing health care for enrollees in Apple Health. HCA leads the Healthier Washington effort through a partnership with the Department of Social and Health Services and the Department of Health. An interagency team encompassing eight other offices including the Department of Early Learning, the Office of Financial Management, and the Governor’s Health Policy Office provided input and expertise throughout the development of the Healthier Washington framework and continue to collaborate. They also provide governance and oversight to the initiative. Together, these agencies and offices work to achieve better health for all Washingtonians.

MCOs Play a Key Role in Moving Health Care Upstream to Address Social Determinants of Health

MCOs play a major role in coordinating the health of Washington’s Medicaid enrollees. In addition to providing clinical care and serving as risk-bearing entities for the delivery of care, these organizations work as facilitators of upstream and population health transformation in the state. MCOs serve on ACHs governing boards and councils, working as thought partners and collaborators within the communities. To meet the needs of each community, they hire regionally-based employees and coordinate services with local organizations. Additionally, the MCOs work collaboratively with the HCA and other Healthier Washington stakeholders to address the issues and needs of the ACHs in order to better serve the regions. The five Washington-based MCOs also work together to build strong provider networks and improve health care savings across the state.

A Regional Health Approach Requires an Integrator Entity Like Washington’s ACHs

While the ACHs do not provide care, they coordinate priority setting and action through governing bodies, and they receive operational support from local community-based organizations, public health agencies, and nonprofits. They also solicit engagement from the public via community meetings, among other strategies. Though identifying the right ACH membership and actually getting those people to sit down to make decisions together was time-consuming and often challenging, many ACHs reported that the process was beneficial. Specifically, several described the importance of having a forum for stakeholders, who would otherwise never interact, to meet regularly to identify opportunities being missed and gain new perspectives (Center for Community Health and Evaluation, 2016). Through these continued meetings and the open sharing of ideas, trust between individuals and the sectors they represent is gradually being built. And, as trust is established it will become easier for ACH members to set aside their personal interests in the interest of the ACH and the region as a whole.

States Should Be Intentional About Learning and Spreading Lessons Learned Among the Clinical Community

The Practice Transformation Support Hub (the Hub), a tool funded by the SIM grant, establishes a regional health connector network that connects clinical providers with local resources, tools, and trainings designed to help clinicians implement and adopt integrated payment models. The Hub, which is managed by the Department of Health, helps spread knowledge of best practices and evidence-based outcomes while facilitating cross-sector communication, referrals, and clinic to community prevention linkages, that is, strategies that link traditional clinical care with community-based initiatives to address chronic disease (Washington State HCA, 2017).

The Creation of Robust Data Systems Drives Progress

Creation of a robust and accessible data collection and reporting system is vital to facilitating the process of tracking local, regional, and statewide health progress, which can be used to target interventions to specific communities or inform policy changes that could have broader population-level implications. In fact, data collection and dissemination is a cornerstone of Healthier Washington, with $25 million of the SIM grant earmarked for analytics, interoperability, and measurement (Aaseby, 2016). These three fronts create new, and leverage existing, analytic tools; build new infrastructure for shared analytics across agencies; and analyze and disseminate health and social determinants data to all agencies through this new infrastructure. Covering the spectrum from prevention to acute care to chronic disease management, one of the existing tools leveraged by these analytics is the Common Measure Set for Health Care Quality and Cost, which consists of more than 50 measures to track, as the name suggests, health care quality, performance, and cost (Washington State HCA, 2014). Developed by a governor-appointed committee, these measures were designed in keeping with HB 2572, section 6, with the expectation that all payers will incorporate these measures into their value-based purchasing contracts, creating a statewide standard set of measures. Data collected from these core measures across communities are available to hospitals and providers so they can make practice-level changes as needed to improve individual care.

As part of HB 2572, the state also created an all-payer claims database. One of few such databases in the country, when combined with the state’s integrated social service database, which is linked to numerous data sources including statewide crime and incarceration rates, school enrollment, and employment information, Washington State will be able to access claims and encounter data to analyze the costs, risks, and outcomes for individuals who access social and health care programs.

A Strong Evidence Base Should Both Inform Decision Making and Ensure Sustainability

Without a data collection and analysis infrastructure built into the Healthier Washington framework, it would be impossible to make comparisons among regions, to build an evidence base of what programs are working, and to then scale up the most effective programs to maximize their effect across the state. Evidence is needed to change provider behavior to improve the health of the individual and to effectively advocate for policy change that could improve the health of the population. As an added benefit, alignment of data repositories and performance measures helps to reduce “provider fatigue.”

The standardization of measures across regions and settings, statewide linkages of multisector data repositories, and improved transparency of data collection procedures all work together to support efficiency and reduce waste in the provision of value-based health care for residents of Washington. And, because delivery system reform incentive payment funds are directly tied to reaching specified project goals, the sustainability of population health improvement in Washington, such as those implemented through ACHs, rely on accurate data collection and reporting. And, if the sustainability of ACHs relies on external funding, they will need to be able to demonstrate their effectiveness to their communities.

Increased Autonomy for ACHs Plus Decreased Burden Equals Improved Health for All

As the ACHs mature, so do their roles and responsibilities, and they are recognizing the need for some autonomy. To ease the burden on ACHs related to the accounting and oversight of the funds earmarked for each, a request for proposals in 2017 will designate a single financial executor to represent all ACHs. The entity will take on all accountability and oversight related to the funds, allowing ACHs to direct their shares as their governing bodies deem fit while also maintaining autonomy over staffing and contracting needs (Washington State HCA, n.d.). Under the delivery system reform incentive payment, ACHs are accountable for achieving certain milestones. By removing the administrative burden of developing accountability and oversight processes from the ACHs and placing it with the financial executor, the ACHs will be able to focus on how to use their funds to improve population health rather than on creating the financial infrastructure needed to collect, distribute, and account for those funds (Cascade Pacific Action Alliance, 2016) [2].

Notes

- Conversation with MaryAnne Lindeblad on January 9, 2017.

- Conversation with MaryAnne Lindeblad on December 16, 2016.

References

- AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2012. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk: Section on breastfeeding. Pediatrics 129(3);e827. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/129/3/e827.full.pdf (accessed January 17, 2017).

- Aaseby A. 2016. Healthier Washington: Analytics, interoperability and measurement. Cascade Pacific Action Alliance Council Meeting. Presented February 11, 2016. Available at: https://crhn.org/pages/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/02_CPAA-AIM-presentation-Final.pdf (accessed April 3, 2017).

- Berwick, D. M., T. W. Nolan, and J. Whittington. 2008. The Triple Aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Affairs 27(3):759-769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Cascade Pacific Action Alliance. 2016. HCA global waiver team visit to CPAA: June 9, 2016 Questions for HCA to consider. Available at: http://crhn.org/pages/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Q_and_A_HCAGlobalWaiver_6-9-16.pdf (accessed April 3, 2017).

- Center for Community Health and Evaluation. 2016. Building the foundation for regional health improvement: Evaluating Washington’s accountable communities of health. Available at: http://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/ach_evalreport_year_1.pdf (accessed April 3, 2017).

- CRHN (CHOICE Regional Health Network). 2016. ACH decision-making and management expectations. Available at: http://crhn.org/pages/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/02_ACH-Decision-Making-and-Management-Expectations-10.27.16.pdf (accessed April 3, 2017).

- Gates, A., R. Rudowitz, and J. Guyer. 2014. An overview of delivery system reform incentive payment (DSRIP) waivers. Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/an-overview-of-delivery-system-reform-incentive-paymentwaivers/ (accessed April 3, 2017).

- Heider, F., T. Kniffin, and J. Rodenthal. 2016. State levers to advance accountable communities for health: Washington State profile. Available at: http://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/WA-State-Profile.pdf (accessed January 19, 2017).

- Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2016. Washington State health care landscape. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/the-washington-state-health-carelandscape (accessed November 9, 2016).

- Rudolph, L., J. Caplan, K. Ben-Moshe, and L. Dillon. 2013. Health in all policies: A guide for state and local governments. Washington, DC and Oakland, CA: American Public Health Association and Public Health Institute. Available at: https://www.apha.org/~/media/files/pdf/factsheets/health_inall_policies_guide_169pages.ashx (accessed December 27, 2016).

- Washington State HCA. 2014. Washington State common measure set for health care quality and cost. Available at: http://www.hca.wa.gov/sites/default/files/pmcc_final_core_measure_set_approved_121714.pdf (accessed November 15, 2016).

- Washington State HCA. 2016a. Accountable communities of health. Available at: http://www.hca.wa.gov/file/ach-regions-maps (accessed November 9, 2016).

- Washington State HCA. 2016b. HCA value-based road map, 2017-2021. 2016b. Available at: http://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/vbp_roadmap.pdf (accessed April 3, 2017).

- Washington State HCA. 2017. Practice transformation support hub. Available at: http://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/healthier-washington/practice-transformation-support-hub (accessed April 3, 2017).

- Washington State HCA. n.d. State innovation model contractual guidelines for accountable communities of health. Available at: http://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/contractual-guidelines-for-ach.pdf (accessed April 3, 2017).