Burnout, Stress, and Compassion Fatigue in Occupational Therapy Practice and Education: A Call for Mindful, Self-Care Protocols

TW: suicide

Now more than ever is the time for occupational therapy educators, students, and practitioners to invest in strategies to combat burnout and stress. Current health care practice requires occupational therapy practitioners to manage many dimensions of patient care. Combining professional and educational duties with the emotional energy required for patient encounters and managing one’s personal life can create the potential for burnout and compassion fatigue and an imbalanced professional quality of life (Stamm, 2010). Yuen (1990) called upon occupational therapy fieldwork educators to put more time in their formal training toward teaching experiences with their students, and to recognize potential for burnout by increasing self-awareness.

Assuming the role of teacher and mentor to a fieldwork student, while simultaneously managing one’s caseload, adds to this potential stress. In entering this collaborative and didactic relationship, occupational therapy practitioners are called upon to offer mindful, compassionate care and their full empathic engagement in every patient or student interaction, drawing from a source of wellness, strength, resilience, and presence (Etzrodt, 2008; Jamieson et al., 2006; Peloquin, 2007; Reid, 2009, 2011; Shapiro and Carlson, 2009). Stress, compassion fatigue, and burnout may decrease therapist satisfaction with work and affect in-the-moment attention in patient and student encounters. A lack of attentive presence negatively affects patient-centered care, student’s learning, and workplace or school morale, and it leads to an increase in staff turnover and absenteeism (Schwerman and Stellmacher, 2012; Taylor, 2008). The trickledown effect may contribute to decreased patient outcomes and decreased patient satisfaction with care received. Students may report decreased satisfaction with their educational experiences. Treatment and documentation errors increase while time and energy resources for patients and students fall (Boyle, 2015; Figley, 1995; Joinson, 1992; Sabo, 2011).

Occupational therapy educators have the responsibility to model self-management to students by balancing between negative and positive factors of work. Practitioner-educators teach and mentor students, in the context of patient care, by modeling professional behaviors, clinical reasoning skills, therapeutic use of self-care, and lifelong learning (Higgs and McAllister, 2005; Stutz-Tanenbaum and Hooper, 2009; Wicks, 2008). Student success is not limited to clinical skill development, but includes observing and prioritizing a learned understanding of balancing quality of life between patient care, role demands, and external life factors. The multiple roles contribute to lived experiences of role strain, role overload, a lack of identity, reduced connection to peers, workload pressures and time constraints, and a sense of incongruence, as reported by occupational therapy fieldwork educators (Barton et al., 2013; Higgs and McAllister, 2005; Roberts et al., 2015; Stutz-Tanenbaum and Hooper, 2009).

A Call for Mindful Self-Care

Physicians, nurses, psychologists, counselors, and social workers are many of the disciplines participating in mindfulness programs to address stress and its manifestations—which are inherent in the nature of their practitioner roles and workplace environments (Baer, 2003; Balk et al., 2009; Epstein, 1999; Fortney, 2011; Krasner et al., 2009; Lawson and Myers, 2011; Schwerman and Stellmacher, 2012; Shapiro et al., 1998, 2005, 2007; Zeller and Levin, 2013). Mindfulness asks an individual to bring the present moment and the self into nonjudgmental awareness. There are many mechanisms by which mindfulness facilitates stress reduction. For example, mindfulness is helpful in the cultivation of one’s “awareness of sensations, thoughts, and feelings as different from the sensations, the thoughts, and the feelings themselves” (Kabat-Zinn, 1990, p. 297). This awareness brings a fundamental shift in perspective out of one’s personal, subjective narrative to a more holistic, nonjudgmental, and objective awareness of the moment, thereby clarifying values. Mindfulness practices include didactic components, breathing exercises, sitting and walking meditations, body scans, gentle yoga, and more, all while paying attention to thoughts and feelings without judgment (Kabat-Zinn, 1990).

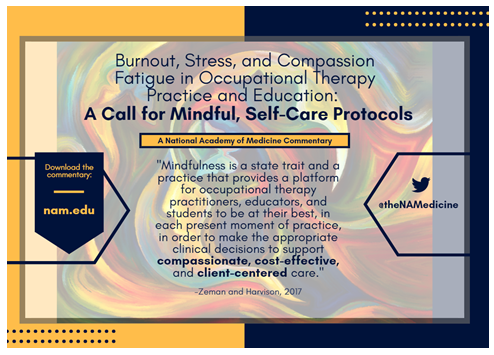

Mindfulness self-care protocols are being employed as a work-wellness platform in health care settings and institutions of higher education. These programs demonstrate outcomes of improved quality of care and reported patient satisfaction, as well as practitioner, student, and educator report of improved well-being, decreased burnout, greater presence and mindfulness, and self-management (Krasner et al., 2009; Lawson and Myers, 2011; Schwerman and Stellmacher, 2012; Shapiro et al., 1998, 2005, 2007; Taylor, 2008). Luken and Sammons (2016) make a case for occupational therapy to join their health sector peers by implementing or exposing students, educators, and practitioners to curricula and programs that explore the facets of mindfulness and its effects on self-management. To date, only a limited number of occupational therapy studies have explored the positive scope of mindfulness training as an important thread in occupational therapy education programs, with findings concentrated in students’ perceived experiences and implementation of mindfulness to their own lives, and less on patient outcomes (Gura, 2010; Luken and Sammons, 2016; Reid, 2013; Stew, 2011). Stew (2011) found that students on clinical placements reported more frequently employing breathing techniques during stressful and challenging situations with patients. Patients receiving care from occupational therapy students participating in a study by Walloch reported improved pain management techniques, by learning, through mindfulness meditation, to separate emotional responses to pain from the unavoidable, sensory aspect of pain (Stew, 2011; Walloch, 1998). Such coping mechanisms can improve patient occupational performance and engagement in everyday activities (Stew, 2011; Walloch, 1998). Reid (2013) suggests researching how occupational therapy practitioners would benefit from mindfulness education is the next logical step. Patient outcomes of those practitioners participating in mindfulness may then be gathered and analyzed to complete the continuum of student–practitioner-patient experiences of a health care relationship. Mindfulness is a state-trait and a practice that provides a platform for occupational therapy practitioners, educators, and students to be at their best, in each present moment of practice, in order to make the appropriate clinical decisions to support compassionate, cost-effective, client-centered care.

Moving Forward

Robert Wicks (2008) states in his book, The Resilient Clinician, “It is not whether stress will appear and take its toll, it is to what extent professionals take the essential steps to appreciate, limit, and learn from this very stress to continue—and even deepen—their personal lives and roles as helpers and healers.” Occupational therapy educators and practitioners are called to collaborate with students to educate, learn, and practice using an array of clinical and self-care tools to provide compassionate patient-centered care. Mindfulness awareness and self-care protocols may guide occupational therapy practitioners, educators, and students to access adaptive coping skills to orchestrate the educator, student, and practitioner roles with personal life. Combating stress, compassion fatigue, and burnout states becomes possible while making room for essential, attentive presence in student and therapeutic encounters—and greater patient and student outcomes and satisfaction is a potential outcome.

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- Baer, R. A. 2003. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 10(2):125-143. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg015

- Balk, J. L., S. C. Chung, R. Beigi, and M. Brooks. 2009. Brief relaxation training program for hospital employees. Hospital Topics 87(4):8-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00185860903271884

- Barton, R., A. Corban, L. Herrli-Warner, E. McClain, D. Riehle, and E. Tinner. 2013. Role strain in occupational therapy fieldwork educators. Work 44(3):317-328. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-121508

- Boyle, D. A. 2015. Compassion fatigue: The cost of caring. Nursing 45(7):48-51. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000461857.48809.a1

- Epstein, R. M. 1999. Mindful practice. JAMA 282(9):833-839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.9.833

- Etzrodt, G. M. 2008. Taking care of our patients and taking care of ourselves. Mental Health Special Interest Section Quarterly 31(3):1-4.

- Figley, C. 1995. Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In Secondary traumatic stress: Self-care issues for clinicians, researchers, and educators, edited by B. H. Stamm. Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press. Pp. 3-28.

- Fortney, L. 2011. Mindfulness for physician burnout. Alternative Medicine Alert 14(9):104-106. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285951719_Mindfulness_for_physician_burnout (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Gura, S. T. 2010. Mindfulness in occupational therapy education. Occupational Therapy in Health Care 24(3):266-273. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380571003770336

- Higgs, J., and L. McAllister. 2005. The lived experiences of clinical educators with implications for their preparation, support and professional development. Learning in Health and Social Care 4(3):156-171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-6861.2005.00097.x

- Jamieson, M., T. Krupa, A. O’Riordan, D. O’Connor, M. Paterson, C. Ball, and S. Wilcox. 2006. Developing empathy as a foundation of client-centered practice: Evaluation of a university curriculum initiative. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 73(2):76-85. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.05.0008

- Joinson, C. 1992. Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing 22(4):116, 118-119, 120. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1570090/ (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Kabat-Zinn, J. 1990. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delacorte Press.

- Krasner, M. S., R. M. Epstein, H. Beckman, A. L. Suchman, B. Chapman, C. J. Mooney, and T. E. Quill. 2009. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA 302(12):1284-1293. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1384

- Lawson, G., and J. E. Myers. 2011. Wellness, professional quality of life, and career-sustaining behaviors: What keeps us well? Journal of Counseling & Development 89(2):163-171. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00074.x

- Luken, M., and A. Sammons. 2016. Systematic review of mindfulness practice for reducing job burnout. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 70(2):1-10. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2016.016956

- Peloquin, S. M. 2007. A reconsideration of occupational therapy’s core values. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 61(4):474-478. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.61.4.474

- Reid, D. 2009. Capturing presence moments: The art of mindful practice in occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 76(3):180-188. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740907600307

- Reid, D. 2011. Mindfulness and flow in occupational engagement: Presence in doing. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 78(1):50-56. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2011.78.1.7

- Reid, D. T. 2013. Teaching mindfulness to occupational therapy students: Pilot evaluation of an online curriculum. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 80(1):42-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417413475598

- Roberts, M., M. E. Evenson, M. A. Barnes, J. Kaldenberg, and R. Ozelie. 2015. Fieldwork education survey: Demand for innovative and creative solutions. OT Practice Magazine 20(9):15-16. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317820849_Fieldwork_education_survey_Demand_for_innovative_and_creative_solutions (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Sabo, B. 2011. Reflecting on the concept of compassion fatigue. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 16(1):1. Available at: https://ojin.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol-16-2011/No1-Jan-2011/Concept-of-Compassion-Fatigue.html (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Schwerman, N., and J. Stellmacher. 2012. A holistic approach to supporting staff in a pediatric hospital setting. Workplace Health & Safety 60(9):385-390. https://doi.org/10.1177/216507991206000903

- Shapiro, S. L., and L. E. Carlson. 2009. The art and science of mindfulness: Integrating mindfulness into psychology and the helping professions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Shapiro, S. L., G. E. Schwartz, and G. Bonner. 1998. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 21(6):581-599. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018700829825

- Shapiro, S. L., J. A. Astin, S. R. Bishop, and M. Cordova. 2005. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. International Journal of Stress Management 12(2):164-176. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.12.2.164

- Shapiro, S. L., K. W. Brown, and G. M. Biegel. 2007. Teaching self-care to caregivers: Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of therapists in training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology 1(2):105-115. https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3918.1.2.105

- Stamm, B. H. 2010. The concise ProQOL manual, 2nd ed. Pocatello, ID: ProQOL.org.

- Stew, G. 2011. Mindfulness training for occupational therapy students. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 74(6):269-276. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802211X13074383957869

- Stutz-Tanenbaum, P., and B. Hooper. 2009. Creating congruence between identities as a fieldwork educator and practitioner. Education Special Interest Section Quarterly 19(2):1-4.

- Taylor, R. R. 2008. The intentional relationship: Occupational therapy and use of self. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

- Walloch, C. L. 1998. Neuro-occupation and the management of chronic pain through mindfulness meditation. Occupational Therapy International 5(3):238-248. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.78

- Wicks, R. J. 2008. The resilient clinician. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Yuen, H. K. 1990. Fieldwork students under stress. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 44(1):80-81. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.44.1.80

- Zeller, J. M., and P. F. Levin. 2013. Mindfulness interventions to reduce stress among nursing personnel: An occupational health perspective. Workplace Health & Safety 61(2):85-90. https://doi.org/10.1177/216507991306100207