Advancing the Health of Communities and Populations: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

Introduction

We have a long way to go to strengthen the public health system to provide adequate protection for communities. Dollar for dollar our health care expenditures fail to provide us with good health at the most basic level as measured by life expectancy and infant mortality. The United States spends 18% of its gross domestic product—more than $8,000 per person per year—on the provision of medical care and hospital services. That is 2.5 times the average of industrialized nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), but by any measure our population is less healthy; US life expectancy at birth is well below the OECD average, and our infant mortality is higher than that of all 26 other industrialized nations. In fact, Americans are at a disadvantage at every stage of the life cycle relative to counterparts in peer countries (NRC and IOM, 2013).

Recent events like lead contamination in drinking water in Flint, Michigan, and other cities across our country; the epidemic of obesity and related chronic diseases in the United States; outbreaks of new microorganisms in drinking water like naegleria and legionella; spread of Aedes mosquitos that carry tropical diseases like Zika, dengue, and chikungunya; the serious impacts of catastrophic storms like Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy; and the epidemics of opiate addiction and HIV that are reappearing across the United States are ringing alarm bells about our weak public health system.

The World Health Organization has defined health as “the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1948). Health of nations and other population groups can be compared via use of health outcome metrics that reflect both positive and negative states of health. Such metrics include: “1) life expectancy from birth, or age-adjusted mortality rate; 2) condition-specific changes in life expectancy, or condition-specific or age-specific mortality rates; and 3) self-reported level of health, functional status, and experiential status” (Parrish, 2010).

The United States should be capable of meeting or exceeding levels of good health enjoyed by people in other countries. Most factors that influence health are embedded in daily life circumstances apart from interactions with the health care system. These factors have to do with social, environmental, and behavioral influences on health that affect everyone in the population. We need to address environmental factors that range from exposure to pathogens, harmful substances, and pollutants to the widely available and aggressively promoted sugary drinks; foods high in salt, fat, and sugar; tobacco; and alcohol products. Behavioral factors can be addressed, as in successful efforts to reduce smoking, but even in the case of smoking, efforts need to be intensified and directed more precisely to populations at greatest risk of tobacco-related chronic diseases. Addressing social, behavioral, and environmental factors that discourage healthy eating patterns or promote unhealthy exposures like smoking—public health—ensures conditions in which people can be healthy.

In the face of our elaborate and expensive health care system, there is direct and undeniable evidence that there are major opportunities to improve population health that lie outside this system or require fundamental changes in how the system operates. There is strong evidence that investments in prevention at the population level, via public health expenditures, are very effective in promoting health and wellness and reducing costs of medical care (McCullough et al., 2012). People who have social and economic advantages have a greater chance of achieving and maintaining good health in spite of adverse environmental exposures compared to people who are disadvantaged by such factors as chronic poverty, lack of education, racial or ethnic discrimination, and geographic isolation. In part, the poor US performance on key health measures reflects the apparent greater effect of such disadvantages in the United States than in peer countries. Peer countries may mitigate social disadvantages better through institutionalized universal and targeted social and economic programs (McLeod, et al., 2012). Health economists are beginning to demonstrate that investments in social services (along with public health) also generate positive health impacts as assessed by a number of measures including obesity, asthma, mental health status, lung cancer, heart attacks, and type 2 diabetes (Bradley et al., 2016).

As defined by Kindig and Stoddart, population health refers to “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group” (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003). Historically in the United States (Jacobson and Teutsch, 2012), health care evolved in two, mostly separate, systems—one that provides clinical care, is largely private, and provides individual prevention and treatment to patients, and a second public health system that is mostly governmental and provides population-based health promotion and disease prevention strategies to people who reside in entire geopolitical jurisdictions. Jacobson and Teutsch have proposed that it might be clearer to use the term “total population health” when referencing actions to improve health in entire geographic regions, to distinguish this concept from the growing use of the term “population health” to reference actions to improve health among groups of people served by various health providers, health insurance systems, and/or specific governmental programs (Jacobson and Teutsch, 2012). In this paper, the term population health should be viewed as synonymous with the concept of total population health. In this context, population health is concerned not only with delivering preventive services to individuals, or groups, but also with addressing broader social and environmental determinants of health in entire regions. (Some might refer to this same concept as community health.)

Traditionally, the “public health” side of the US two-part health system has had the responsibility for populations in organizational and financial arrangements that are largely separated from the treatment side. Recognition of the need to bring these subsystems together has increased over time. The shift in thinking toward a more comprehensive approach to achieving population health and wellness was prominent in the advice of the Secretary for Health’s Task Force on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020 and in the character of the subsequent federal health objectives for this decade (Fielding et al., 2014).

As noted below, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) included a number of provisions that support total population health approaches within the health care system, including both traditional public health efforts as well as efforts to better integrate total population health and health care.

Opportunities for Progress and Policy Implications: A Call for Change

The many excellent efforts under way to revitalize, expand, and innovate in advancing the health of populations and communities indicate that the United States is at a critical inflection point for taking more deliberate and effective actions to improve public health and prevention capacity. Such efforts are both expanding access to health care and are extending outside the health sector and, if supported and expanded, create major opportunities for improving the health of populations and communities. These efforts include the establishment of the Prevention and Public Health Fund under the ACA, community needs assessments under the ACA, the establishment of minimum standards for state and local public health programs, support of community-based programs and coalitions, a new Office of Disease Prevention in the National Institutes of Health, and health and wellness programs in corporations. These recent developments have set the stage for making major improvements in population health in the United States.

In addition, many far-reaching recommendations relevant to improving population health outcomes have emerged from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in recent years. While supporting those longer-term recommendations, this paper identifies potentially transformative initiatives that can be implemented quickly with relatively little incremental expense. These initiatives are predicated on a vision of a healthy community as a “strong, healthful and productive society, which cultivates human capital and equal opportunity. This vision rests on the recognition that outcomes such as improved life expectancy, quality of life, and health for all are shaped by interdependent social, economic, environmental, genetic, behavioral, and health care factors, and will require robust national and community-based policies and dependable resources to achieve it” (National Prevention Council, 2011).

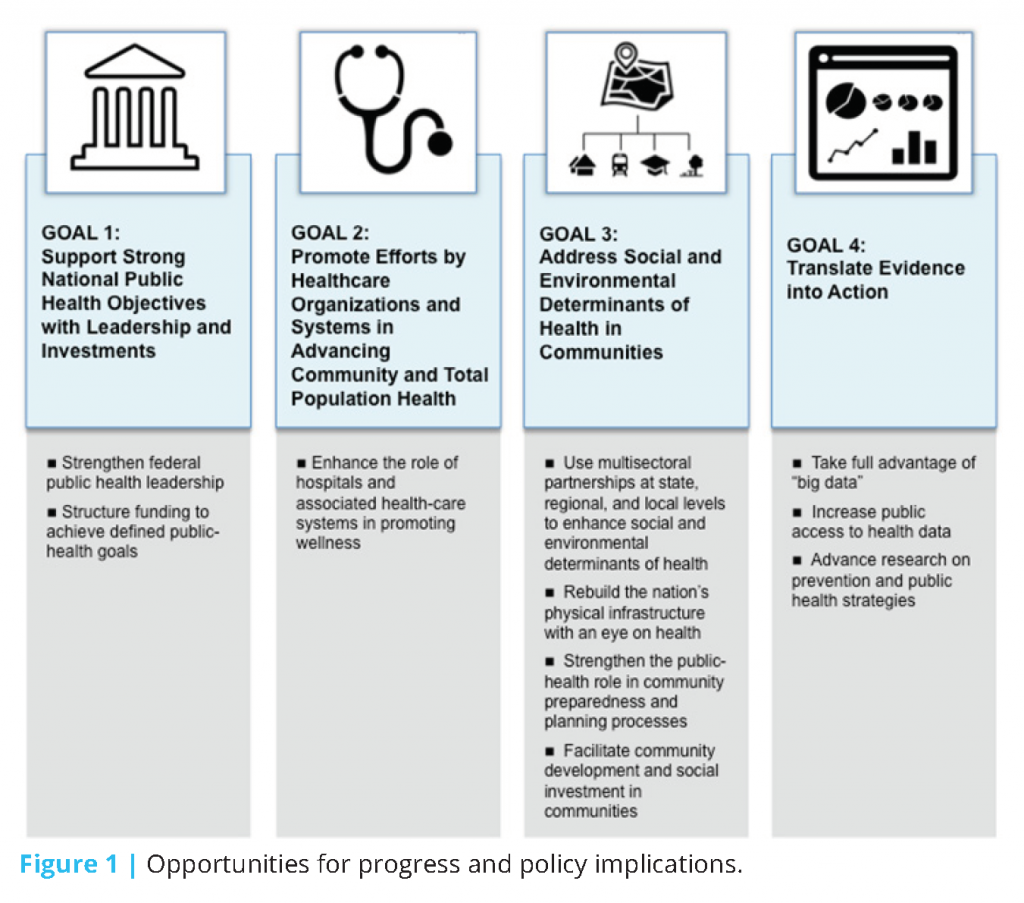

These recent developments set the stage for a number of specific opportunities to set the nation’s prevention and public health efforts on a new path (Figure 1).

Goal 1: Support Strong National Public Health Objectives with Leadership and Investments

The achievement of health goals for communities—total populations—is quite challenging in that many of the factors that influence health are not, and never will be, controlled or directed by the health sector. Public health leaders exert influence in many ways, for example, with information and recommendations (e.g., successive Surgeon General’s reports), through influencing (e.g., First Lady Obama’s campaign to promote healthy eating and physical activity), and through work in local communities.

The US Department of Health and Human Services’ (DHHS) Healthy People 2020 initiative, with input from thousands of members of the public and organized public health and health groups, culminated in more than 1,200 objectives, from which DHHS leadership identified a set of 26 Leading Health Indicators that are tracked at various government levels (Koh et al., 2014). That approach can support implementation of a recommendation of a recent consensus study of the National Academies that “The Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services should adopt an interim explicit life expectancy target, establish data systems for a permanent health-adjusted life expectancy target, and establish a specific per capita health expenditure target to be achieved by 2030. Reaching these targets should engage all health system stakeholders in actions intended to achieve parity with averages among comparable nations on healthy life expectancy and per capita health expenditures” (NRC and IOM, 2013).

Building on this, a White House-led effort could bring to bear political leadership—across the entire federal government—to invoke more integrated action across sectors and investments in communities to achieve health via application of a Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach. Developed in Finland, HiAP has been adopted by the European Union and has been credited with resulting in an increased focus on population health in a number of areas, including social services, diet, nutrition and physical activity, alcohol policies, environmental and health consequences of transport, and mental health impact assessment of public policies (Puska and Ståhl, 2010).

Opportunity: Strengthen Federal Public Health Leadership

Within the United States, the National Prevention Council (NPC) is an example of a HiAP-oriented initiative at the federal level. This Council, which is chaired by the Surgeon General, brings together representatives from 20 federal departments, agencies, and offices, including sectors such as housing, transportation, education, environment, and defense. The National Prevention Strategy (National Prevention Council, 2011), developed by the NPC with broad input from diverse stakeholders, needs to be raised to a much higher level of priority in the administration. This includes creating a stronger focus in the White House with adequate funding and decision authority to coordinate multisectoral population health and prevention efforts throughout the government and by vesting stronger authority at the highest levels in the DHHS to align all DHHS activities with population health and prevention goals. Such leadership in the White House could be achieved via strengthening the role of the Domestic Policy Council (DPC) in population health promotion, or via establishment of a new office. The role of the Secretary of DHHS and other leaders could be elevated. Of note, both the DPC and the Secretary of DHHS have congressional authority to undertake such an initiative already. Such efforts can build upon the NPC’s National Prevention Strategy. Finally, the administration needs to be a clear champion of the concept that investing in prevention has high priority and has a greater proven return than does other health care investment (McCullough et al., 2012).

The HiAP approach has been supported by a tool called the Health Impact Assessment (HIA), which can be applied when a more formal assessment is required (Wernham and Teutsch, 2015). Many have suggested formal adoption of an HIA approach in the United States, and there is an emerging body of evidence for its applicability (IOM, 2014). By Executive Order the White House could require explicit consideration of health impacts (or benefits) for major federal expenditures.

Specific White House coordination could help support activities to promote health in communities. Such an effort could build on the last administration’s “Sustainable Communities” initiative (which included housing, environment, and transportation but not health.) It could benefit from a number of initiatives that have been carried out by the private sector to address housing and economic opportunity, environmental health, and access to health services in communities to improve health (Acosta et al., 2016).

Less obvious but perhaps of equal importance is tax policy. For example, there are corporate tax credits for affordable housing ($7.8 billion for 2016), wind power ($2.9 billion in 2016), and orphan-drug research ($900 million). There are exclusions and deductions for “research and experimentation” ($5.8 billion), domestic production ($13.2 billion), and charitable contributions to health organizations ($1.9 billion) (US Treasury, 2016). There are numerous opportunities in existing tax policies for the White House to enhance the health benefits for communities and promote a full-scale population health improvement strategy.

The White House could also consider the development of an Opportunity Development Bank, a public–private partnership that is dedicated to infrastructure development and invests tax revenues at high rates of economic and social return. The investments could include early childhood interventions, preschool enhancements, juvenile justice diversion programs, high school counseling programs, adult job training programs, adult criminal rehabilitation, substance use prevention programs, housing support, and library expansions. Returns on such investment potentially can be extremely high (Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 2016). Some programs have a rate of return as high as 100%; the social returns can be even higher, perhaps $15 or $20 for every dollar invested.

Opportunity: Structure Funding to Achieve Defined Public Health Goals

According to the National Academies, a minimum set of public health services is needed in every community (IOM, 2012). In 2012, it recommended that Congress “authorize a dedicated, stable, and long-term financing structure to generate the enhanced federal revenue required to deliver the minimum package of public health services in every community.” It also stated that “such a financing structure should be established by enacting a national tax on all medical care transactions to close the gap between currently available and needed federal funds” (IOM, 2012).

Congress and the administration can work together to define the public health services that could be supported by the federal government and others and to enact legislation that would authorize and appropriate resources, including funding, for these purposes.

Goal 2: Promote Efforts by Health Care Organizations and Systems in Advancing Community and Total Population Health

Health care organizations and systems, both public and private, need support in expanding their missions and activities to include a focus on the maintenance of good health and well-being in the people and communities that they serve. The traditional focus on disease screening and treatment reinforces a focus on health problems at a relatively late stage in the process and is not cost-effective (McCullough et al., 2012). It discourages accountability for overall community and population health and engagement in the large-scale community-based health-promotion and disease-prevention activities of which medical encounters are only one aspect.

For many years the public health system has been engaged in providing access to medical care for underserved populations as well as promotion of clinical preventive services like immunizations, blood pressure screening, and cancer screening. Developments of the last few years are shifting many of these clinical preventive activities into the clinical care system; at the same time, until all Americans have access to health care, the public health system will continue to be responsible for safety net function. More recently, the clinical care system is seeking the achievement of the “Triple Aim” that was proposed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI, 2016), and seeks to simultaneously lower the costs of health care, improve the quality of health care delivery, and improve health outcomes among the populations that are served. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has embraced the concept of population health promotion under the triple aim and there is evidence of progress in several areas. Under the ACA, federal funds can be used for US Preventive Services Task Force approved preventive services without copay. The ACA has also permitted the use of federal health care funds for community-based prevention for the first time (the PH Trust Fund). Additionally, the movement toward Medicaid and Medicare managed care and increasing incentives for managed Medicare and Medical Homes are examples of financial incentives that are beginning to reward prevention activities in the context of individual patient care. All of these activities are laying the groundwork for more engagement of health care organizations and systems in advancing community and total population health.

Opportunity: Enhance the Role of Hospitals and Associated Health Care Systems in Promoting Wellness

Community benefits requirements for nonprofit hospitals under Internal Revenue Service (IRS) 501(c)(3) regulations have foreseen the benefits of changes in progressive hospital and community systems (Rosenbaum, 2016). We would favor refining community benefits requirements to provide incentives to regional efforts and to ensure the inclusion of local health departments and public health schools and programs in analysis and planning efforts. Those efforts are accountable to hospitals’ community benefits obligation, except where community benefits funds are already subsidizing Medicaid or uncompensated care, and generate a large amount of revenue, more than $24 billion in 2011 (Rosenbaum et al., 2015). Such activities include generation of community demographic and health data and community engagement and participation functions. Specific policies could include erasing the distinction between community health improvement and community building, creating a new IRS category for priorities identified in total population health needs assessments, offering incentives for multi institutional pooling, and encouraging hospitals to move toward allocating the full value of their tax benefit to community health improvement and charity care.

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) emerged as a component of the ACA as a means of encouraging health care providers to coordinate care throughout the spectrum of wellness, prevention, and treatment, with shared accountability and risk. Hundreds of ACOs have been formed, and some have led to better outcomes, lower total costs, and improved patient care and experiences (Kassler et al., 2015). Even so, ACOs as currently constructed entail only traditional components of medical care and have yet to develop comprehensive wellness models that incorporate other elements of prevention and wellness. For example, oral health services continue to be marginalized rather than embraced as a vital feature of population health, particularly in low-income and otherwise vulnerable populations, despite recognition by CMS in 2011 that “oral health [should be] included in . . . the Accountable Care Organization demonstration” and that the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation should “develop innovative scalable models for the delivery of oral health care” (CMS, 2011). Drawing from the initial success of many ACOs, the model needs to be more expansive in this and other fields, such as mental health.

The principal role of Medicaid is to be the provider of health insurance for the poor. However, it also has a tradition of promoting health and wellness. As Medicaid continues to expand and evolve, state waivers are increasingly extending its reach to promote better health for the underserved. That affords an opportunity to test new models and partnerships between health care providers and community-based programs that have been shown to improve social conditions that promote well-being. CMS could be given more authority to waive Medicaid rules and work with states to accelerate the incorporation of prevention and population health into state Medicaid programs. Outcomes related to improved total population health and reduction in health disparities should be included as valid outcomes of Medicaid.

Goal 3: Address Social and Environmental Determinants of Health in Communities

Because no two communities are exactly alike, strong community engagement not only by local public health agencies and health care providers but also by housing, environmental, financial, transportation, and other sectors is needed to address social and environmental determinants of health. How we build and maintain our homes, buildings, and cities and the infrastructure for transportation, physical activity, drinking water, and sanitation has a critical effect on our health. Moreover, communities will not be healthy unless all are served equitably. Current fragmented approaches exacerbate health inequities, but multisectoral approaches improve equity. In many ways such efforts reflect application of the HiAP approach at a local level.

Opportunity: Use Multisectoral Partnerships at State, Regional, and Local Levels to Enhance Social and Environmental Determinants of Health

To carry out the population health improvement planning and resource mobilization that we call for, the administration could stimulate and assist in funding of broad multisectoral partnerships that promote total population health. Many communities across the country already are creating community health agendas, leveraging assets, making health a locally defined issue in which everyone has a stake, and moving policy change at the local and regional levels. But too few health departments have the resources needed to lead such community efforts. A federal effort to support community multisectoral partnerships could be launched in 100 communities across the country in a 3-year program to establish national models. Effects measured should include educational, public safety, and economic indicators and health indicators already defined in Healthy People 2020.

Opportunity: Rebuild the Nation’s Physical Infrastructure with an Eye on Health

The brown water flowing from spigots in Flint, Michigan, is just the tip of the iceberg for the gradual breakdown in many of our drinking water systems, as well as our neglected transportation systems, sewer systems, and energy distribution systems. Large adverse health and economic consequences are already being felt directly in many communities (ASCE, 2013). We propose a multisectoral approach targeted to jurisdictions with older physical infrastructures that will engage them in an assessment of infrastructure weak spots so that they can plan for and fund community structural improvements—leveraging not only health assets but the Department of Labor, Department of Housing and Urban Development, and other relevant department efforts in a coordinated and collaborative manner. A multisectoral approach is important because much of the work could be funded by the private sector (gas, electric power, water, and sanitation utilities). In New York City, Mayor de Blasio’s Underground Infrastructure Working Group is an example of an effort to bring sectors together to coordinate infrastructure repair work so that it can be done more quickly and efficiently. Congress and the executive branch could pair the effort with existing job-training efforts to prepare people in low-income communities for work in the many sectors that are involved with maintenance and improvement of the physical infrastructure. Public health should inform these efforts so that infrastructure improvements address environmental health and safety issues that are critical for the health of communities.

Opportunity: Strengthen the Public Health Role in Community Preparedness and Planning Processes

Rather than respond to the “disaster of the month” (Zika virus, Ebola, hurricanes, earthquakes, floods, and the like), we need efforts to enable communities to withstand and recover from myriad disastrous events. Such efforts need to anticipate threats, minimize adverse effects on health, and rapidly restore function after a crisis. Community preparedness planning is multisectoral, but public health has an important role to play in ensuring that those who are most vulnerable (such as residents of assisted-living facilities) are protected from health consequences; in strengthening community health systems and integrating them with community resources, including the private sector; and in integrating community preparedness effort with day-to-day planning to combat the health threats posed by daily living and the epidemic of chronic diseases and prevalence of untreated mental illnesses that are the causes of premature death, disability, and diminished quality of life. Collaboration between the private and public sectors could improve the ability of communities to plan, prepare, respond, and recover. It has been shown to work during the recent H1N1 influenza outbreak in which federal, state, and local partnerships addressed a serious epidemic. Public health preparedness systems need to be adequately resourced and sustained if they are to be able to identify the emergence of new health threats and respond to them effectively.

Opportunity: Facilitate Community Development and Social Investment in Communities

Under White House leadership, broadening investment in human capital through new financial vehicles can be encouraged. We bring several ideas to the table to identify new ways to mobilize resources for total population health. Some of these could be led by the White House via consideration of tax and investment policies as described above. Others could emanate from local efforts.

The partnership of the Federal Reserve Bank, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Kresge Foundation has played a key role in connecting financial investment in commercial development and housing to improved health in communities. In several communities, it has facilitated loans in conjunction with philanthropic investment that addresses housing and economic opportunity, environmental health, and access to health services.

Corporations can be involved in ways that go well beyond workplace wellness programs. Direct linkages between local public health agencies, business leaders, community groups, not-for-profit organizations, and the health care community can forge a common language and understanding of employee and community health problems and broaden participation in setting total population health goals and strategies. Corporations can work with government to gather, interpret, and exchange mutually useful data. They can use their knowledge of marketing and social marketing techniques to promote individual behavior and community change (IOM, 2015).

Health care systems and organizations have a key opportunity to create environments for improved population health. If they leverage the entirety of their assets—for example, as employers, purchasers, consumers, and potential energy conservers—the effect of intentional business practices can potentially improve the health of a population more than actual delivery of services. Moreover, studies suggest that a large moderate-income workforce can have a greater role in generating income in a community than a smaller high-income workforce. When income disparities narrow in a community, population health improves.

Goal 4: Translate Evidence into Action

Advancing community and population health requires acting immediately on what we know even while we are setting research priorities and funding mechanisms to strengthen the evidence base of new population health interventions. The DHHS Advisory Committee on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020 identified where taking action on the basis of what we already know about interventions can improve community and population health. This includes evidence on what works and what does not work. The marked increases in the availability of health data to facilitate evidence translation and generation increase the practicability of use for prevention.

Opportunity: Take Full Advantage of “Big Data”

The use of “Big Data” is an emerging field that may be key to the promotion of population health. The term “Big Data” refers to very large datasets obtained from a variety of sources that, if appropriately managed and analyzed, can yield a wealth of detailed information to support achievement of various population health objectives. All efforts related to assessments, planning, preparedness, and development of a common understanding of facts at very granular levels geographically can help to identify social and environmental determinants of health, and give a clearer picture of health status and trends in a number of dimensions (NASEM, 2016). Efforts like the County Health Rankings project, which ranks the more than 3,000 counties in the United States based on a model that combines health outcomes with health factors, provide a basis for identifying communities that most need health improvement efforts, and for rallying support for those efforts across sectors (Remington et al., 2015).

Nationally, billions of dollars have been invested in efforts led by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to individual access to electronic health information as well as connectivity among systems so that information can be shared across systems while protecting data security and privacy (DeSalvo et al., 2015). No such strong national efforts have been undertaken to understand the data needs to support population health efforts. Such efforts should build on clinical data collection to support the broader advancement of population health by standardizing reporting of population health measures (for example, patient-reported measures of wellness and reported health conditions). They should also include geographic and, where possible, individual data relevant to environmental and social determinants of health. A later step would be to aggregate and release this information in a way that complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act to allow policy makers to address issues comprehensively among sectors that currently remain siloed (i.e., to integrate across data with regard to underlying physical and social environments, with data on health and wellness, to assist with community-wide prevention efforts).

Opportunity: Increase Public Access to Health Data

DHHS should expand early success in supporting public availability of health datasets and the development of informatics tools to facilitate aggregation and linkages with related datasets. Data.gov and similar efforts already have helped researchers to understand and policy makers to solve persistent problems related to health effects in association with physical and social environments, factors related to timing and identification of risk factors, and triggers of predictable events. It is of critical importance that public health researchers and policy makers work closely with the health care industry to improve its data so that it can maximize their use for population health. There are substantial opportunities for sharing and commingling of public and private datasets, which would advance the open-data movement to the next level.

Opportunity: Advance Research on Prevention and Public Health Strategies

Community prevention activities are too often undertaken with a weak evidentiary base, largely because the support for such research is meager. Unlike clinical practice, the practice of public health has few opportunities for product development and promotion. The onus is on government to fund public health research.

The National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (IOM) report U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health stated that “the National Institutes of Health and other research funding agencies should commit to a coordinated portfolio of investigator-initiated and invited research devoted to understanding the factors responsible for the US health disadvantage and potential solutions, including lessons that can be learned from other countries” (NRC and IOM, 2013). In addition, the report also recommended that the federal government increase the portion of its budget allocated to population and community-based prevention research that

- Addresses population-level health problems.

- Involves a definable population and operates at the level of the whole person.

- Evaluates the application of discoveries and their effects on the health of the population.

- Focuses on behavioral and environmental (social, economic, cultural, and physical) factors associated with primary and secondary prevention of disease and disability in populations.

CMS has recently funded a number of Health Care Innovation Awards, some of which support linkage between health services and community social services to support the broader needs of individual patients. They have announced an intention of expanding this approach via a recently announced 5-year, $157 million program to test a model called Accountable Health Communities. The CMS Innovation Center will use these grants to “test whether systematically identifying and addressing health-related social needs can reduce health care costs and utilization among community-dwelling Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries” (Alley et al., 2016). Such prevention research explicitly seeks to fund itself through health care savings. However, prevention research funded by other agencies also is an excellent investment even though the costs and savings are not directly linked within their budgets.

A number of efforts have been made to encourage the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to fund more prevention research and these need to be intensified. There are other agencies whose research programs should be strengthened: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Environmental Protection Agency. Federal health research agencies need to focus not only on genetic but also social and environmental determinants of health, both discovery-oriented research about how these determinants cause ill health (or promote wellness) and translational research on how to apply this knowledge to improve health in communities. Such research needs to focus on the most vulnerable, for example, pregnant women, infants, children, the elderly, and those who are genetically vulnerable or immunocompromised.

In the long run, health care expenditures need to help to support a Prevention Research Trust Fund to support Community-Centered Outcomes Research just as we now have support for the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) via the ACA. Such research could be housed in NIH or CDC as a freestanding institute on the model of or within PCORI. It should involve not only academic research but community participatory models that are directed especially to underserved communities and social and environmental determinants of health and that empower communities to manage interventions (Selby et al., 2015). The effort would generate the evidence needed for tackling the most serious public health problems at the community level via research that is difficult to fund through existing avenues in NIH and elsewhere. Priorities for the effort should be drawn from existing expert bodies, such as the Community Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, public health professional and government organizations, and National Academies report recommendations. The research should explicitly address both costs and benefits of prevention strategies.

Conclusion

We have made a number of proposals, of which the most important are related to the establishment of clear points of accountability and leadership for total population health in the United States, both in the White House and in DHHS. The United States can have the best community and population health in the world, but that cannot happen unless such strong public health objectives are articulated and widely shared.

We suggest that not only the public health system, but many other entities will need to play a role if we are to be successful. Health care organizations, both public and private, need to be held accountable for promotion of good health and disease prevention, not only for treatment of the illnesses. Communities need to be accountable for bringing public health agencies together with other sectors in a number of contexts to develop a shared sense of what can be done collaboratively to promote health and to address shortcomings in our physical infrastructure and community preparedness efforts that are increasing risks. The government and the finance communities need to be brought together to pursue new financing strategies for infrastructure investment and community development, including efforts that directly address the social determinants of poor health in communities.

“Big data” needs to be harnessed to support public health and disease prevention efforts. Public health translational research is needed to move discoveries from fundamental bench science and social science to the development and testing of community and population-level interventions. Such research is unlikely to be funded unless a trust fund is created and a government entity is made accountable for ensuring that it is done.

This paper has focused on opportunities to advance the health of the nation through a lens that considers whole communities and focuses on public health or population health approaches to creating or enhancing physical and economic environments for promoting health and preventing diseases. The approaches and opportunities discussed here complement those identified in other Vital Directions discussion papers. In particular, public health approaches can engender transformative changes in the systems and entrenched institutional policies and practices that lower our overall standard of living and perpetuate systemic social disadvantages for some demographic groups; and they can address the “social determinants” of health and achieve health equity (Adler et al., 2016), improve options for healthy eating and physical activity (Dietz et al., 2016), and foster good physical and mental health and well-being throughout the life course. It is essential to recognize the connections among these papers to find strategies that are compatible and mutually reinforcing. For example, many communities that have poor access to services have the highest burden of mental health and substance-abuse problems (Knickman et al., 2016).

The United States has great opportunities to advance the health and well-being of communities and populations at large and to make progress both in saving lives and in reducing the cost of health care. We have identified a number of approaches for moving forward; at the core of all of them is the need to marshal and align forces across sectors and communities toward disease prevention. Achieving the highest possible level of health in communities and populations requires a rebalancing of our overall investment in ways that enhance disease prevention and wellness strategies throughout the lifespan and builds the strength and resilience of communities.

References

- Acosta, J., M. D. Whitley, L. W. May, T. Dubowitz, M. Williams, and A. Chandra. 2016. Stakeholder perspectives on a culture of health: Key findings. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1274.html (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Adler, N. E., D. M. Cutler, J. E. Fielding, S. Galea, M. M. Glymour, H. K. Koh, and D. Satcher. 2016. Addressing Social Determinants of Health and Health Disparities: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201609t

- Alley, D. E., C. N. Asomugha, P. H. Conway, and D. M. Sanghavi. 2016. Accountable health communities—addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. New England Journal of Medicine 374:8-11. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1512532

- ASCE (American Society for Civil Engineers). 2013. 2013 report card for America’s infrastructure. Reston, VA: ASCE. Available at: https://www.infrastructurereportcard.org/making-the-grade/report-card-history/2013-report-card/ (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Bradley, E. H., M. Canavan, E. Rogan, K. Talbert-Slagle, C. Ndumele, L. Taylor, and L.A. Curry. 2016. Variation in health outcomes: The role of spending on social services, public health, and health care, 2000-09. Health Affairs (Millwood) 35:760-768. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0814

- CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2011. Improving access to and utilization of oral health services for children in Medicaid and CHIP programs: CMS oral health strategy. Washington, DC: US Department

of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/downloads/cms-oral-health-strategy.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020). - DeSalvo, K. B., A. N. Dinkler, and L. Stevens. 2015. The US Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Progress and promise for the future at the 10-year mark. Annals of Emergency Medicine

66:507-510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.03.032 - Dietz, W. H., R. C. Brownson, C. E. Douglas, J. J. Dreyzehner, R. Z. Goetzel, S. L. Gortmaker, J. S. Marks, K. A. Merrigan, R. R. Pate, L. M. Powell, and M. Story. 2016. Chronic Disease Prevention: Tobacco, Physical Activity, and Nutrition for a Healthy Start: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201609j

- Fielding, J., S. Kumanyika, and R. Manderscheid. 2014. A Perspective on the Development of the Healthy People 2020 Framework for Improving U.S. Population Health. Public Health Reviews 35:1-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391688

- IHI (Institute for Healthcare Improvement). 2016. IHI Triple Aim Initiative. Cambridge, MA: IHI. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx (accessed July 28, 2020).

-

Institute of Medicine. 2012. For the Public’s Health: Investing in a Healthier Future. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13268

- Institute of Medicine. 2014. Applying a Health Lens to Decision Making in Non-Health Sectors: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18659

-

Institute of Medicine. 2015. Business Engagement in Building Healthy Communities: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/19003

- Jacobson, D. M., and S. M. Teutsch. 2012. An environmental scan of integrated approaches for defining and mea¬suring total population health by the clinical care system, the government public health system, and

stakeholder organizations. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum. Available at: https://www.improvingpopulationhealth.org/PopHealthPhaseIICommissionedPaper.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020). - Kassler, W. J., N. Tomoyasu, and P. H. Conway. 2015. Beyond a traditional payer—CMS’s role in improving population health. New England Journal of Medicine 372:109-111. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1406838

- Kindig, D., and G. Stoddart. 2003. What is population health? American Journal of Public Health 93:380-383. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.3.380

- Knickman, J., K. R. Rama Krishnan, H. A. Pincus, C. Blanco, D. G. Blazer, M. J. Coye, J. H. Krystal, S. L. Rauch, G. E. Simon, and B. Vitiello. 2016. Improving Access to Effective Care for People Who Have Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201609v

- Koh, H. K., C. R. Blakey, and A. Y. Roper. 2014. Healthy People 2020: A report card on the health of the nation. JAMA 311:2475-2476. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.6446

- McCullough, J. C., F. J. Zimmerman, J. E. Fielding, and S. M. Teutsch. 2012. A health dividend for America: The opportunity cost of excess medical expenditures. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43:650-654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.013

- McLeod, C. B., P. A. Hall, A. Siddiqi, and C. Hertzman. 2012. How society shapes the health gradient: Work-related health inequalities in a comparative perspective. Annual Review of Public Health 33:59-73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124603

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Metrics That Matter for Population Health Action: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21899

- National Prevention Council. 2011. National Prevention Strategy. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/disease-prevention-wellness-report.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2013. U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13497

- Parrish, R. 2010. Measuring population health outcomes. Preventing Chronic Disease 7(4):A71. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jul/10_0005.htm (accessed September 11, 2016).

- Puska, P., and T. Ståhl. 2010. Health in all policies—the Finnish initiative: Background, principles, and current issues. Annual Review of Public Health 31:315-328. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103658

- Remington, P. L., B. B. Catlin, and K. P. Gennuso. 2015. The county health rankings: Rationale and methods. Population Health Metrics 13:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-015-0044-2

- Rosenbaum, S. 2016. Hospital community benefit spending: Leaning in on the social determinants of health. Milbank Quarterly 94:251-254. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12191

- Rosenbaum, S., D. Kindig, J. Bao, M. Byrnes, and C. O’Laughlin. 2015. The value of the nonprofit hospital tax exemption was $24.6 billion In 2011. Health Affairs (Millwood) 34:1225-1233. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1424

- Selby, J. V., L. Forsythe, and H. C. Sox. 2015. Stakeholder-driven comparative effectiveness research: An update from PCORI. JAMA 314:2235-2236. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721417700759

- US Treasury. 2016. 2016 Tax Expenditures. US Treasury. Available at: https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/tax-policy/tax-expenditures (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Washington State Institute for Public Policy. 2016. Benefit-cost results: Public health. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy. Available at: https://www.wsipp.wa.gov/BenefitCost (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Wernham, A., and S. M. Teutsch. 2015. Health in all policies for big cities. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 21:S56-S65. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000130

- WHO (World Health Organization). 1948. Preamble: Constitution. Geneva: WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).