Addressing Social Determinants of Health and Health Disparities: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

Introduction

Despite the powerful effects of social and behavioral factors on health, development, and longevity, US health policy has largely ignored them. The United States spends far more money per capita on medical services than do other nations, while spending less on social services (Bradley et al., 2011). Residents of nations that have higher ratios of spending on social services to spending on health care services have better health and live longer (Bradley and Taylor, 2013; NCR and IOM, 2013a). The relative underinvestment in social services helps to explain why US health indicators lag behind those of many countries (Woolf and Aron, 2013). The best available evidence suggests that a health policy framework addressing social and behavioral determinants of health would achieve better population health, less inequality, and lower costs than our current policies.

Overview

For over a century, each generation of Americans has lived longer than did their parents because of advances in health care and biotechnology (Nabel and Braunwald, 2012) and progress in public health and health behaviors (Laing and Katz, 2012; Tarone and McLaughlin, 2012). However, although the US population gained 1–2 years of life expectancy in each decade from 1950 to 2010, life expectancy has since then increased by only 0.1 year (Arias, 2015; Murphy et al., 2015), and some researchers predict that it will decrease for the next generation because of the obesity epidemic (Olshansky et al., 2005). Mortality in middle-aged white women is already increasing, most strikingly in residents of the southern United States and in women who lack a high school degree (Case and Deaton, 2015; Gelman and Auerbach, 2015).

In contrast with the United States, many high-income nations continue to achieve major gains in health and life expectancy. Life expectancy of white men and women in the United States is more than 4 years shorter than that in many European countries and even shorter among blacks (National Center for Health Statistics, 2015); indeed, the United States overall ranks 27th among Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries in life expectancy at birth.

In addition to the relatively poor health of the overall US population, the burden of ill health is unevenly distributed. Differences in health that are avoidable and unjust—referred to as health disparities or health inequities— are greater in the United States than in peer countries, such as Canada or high-income European countries (Avendano et al., 2009; Lasser et al., 2006; Siddiqi et al., 2015; van Hedel et al., 2014). People in less-advantaged groups have worse health from the moment of birth and throughout life. For example, a 40-year-old American man in the poorest 1% of the income distribution will die an average of 14.6 years sooner than a man in the richest 1%; the gap for American women is 10.1 years (Chetty et al., 2016). Health disparities also occur in relation to other aspects of socioeconomic status, such as education and occupation, and in relation to race or ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and place of residence (Adler and Rehkopf, 2008). To a great extent, socioeconomic disparities underlie other bases of health disparities, but they do not account for them fully. Because socioeconomic factors are major, modifiable contributors to disparities, addressing them is a logical way to reduce disparities in multiple dimensions.

Health disparities are not inevitable; actions that lessen social disadvantage can reduce gaps in health and longevity. For example, progress in reducing health inequities between blacks and whites was achieved in the late 1960s and the 1970s after the passage of major civil rights legislation (Almond et al., 2006; Kaplan et al., 2008; Krieger et al., 2008). Contemporary data suggest that despite the worrisome evidence on middle-aged and older adults, patterns in younger people are more encouraging (Currie and Schwandt, 2016).

Those three lines of evidence—the relatively poor health status of the US population compared with other countries, the existence of health disparities, and fluctuations in health and health inequalities in relation to policy-driven changes in social conditions—point to the importance of policies that address social determinants. Such policies, although not typically viewed as “health policies,” have the potential to improve the health and longevity of all Americans and to reduce health disparities.

Key Issues, Cost Implications, and Barriers to Progress

Powerful drivers of health lie outside the conventional medical care delivery system, so we should not equate investment in clinical care with investment in health. Investment in clinical care may yield smaller improvements in population health than equivalent investment that address social and behavioral determinants. To the extent that health care investment crowds out social investment, substantial allocation of resources in clinical care may have an adverse effect on overall health, particularly on the health of the socially disadvantaged. Health policies need to expand to address factors outside the medical system that promote or damage health.

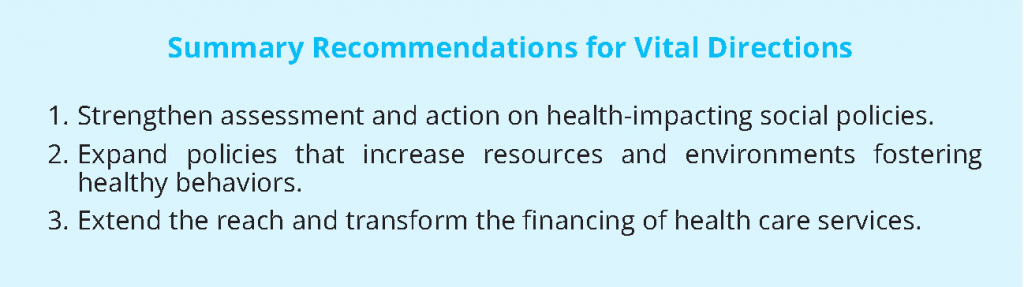

To help frame the policy options, we consider several issues of overriding potential to improve health and diminish health disparities:

- Addressing “upstream” social determinants of health. Accumulating evidence highlights the individual and collective contributions of education, labor, criminal justice, transportation, economics, and social welfare to health. Policies in those domains are increasingly understood to be health policies.

- Fostering health-promoting resources and reducing health-damaging risk factors throughout the life course. Behavioral patterns develop and play out in the context of physiologic and social development, and benefits of early intervention accumulate over one’s lifetime. Policies that make it easier and more socially normative to engage in healthy behaviors have proved effective, as have policies that reduce the harm caused by risky behaviors.

- Improving access to, effects of, and the value of clinical health care services. Differential access to high-quality health care services can create health disparities. These inequities can be rectified by aligning reimbursement strategies to increase access, by expanding the array of services that are reimbursed, and by improving the quality and efficiency of services. Better links between health care and public health activities could increase the effects of health expenditures.

Although policy making is necessary, it is not sufficient. Effective implementation is essential and requires continuing attention and coordination among different parts of government. Gaps between policies and practices have diminished the effects of excellent policy initiatives. For example, a number of policies included in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016) have not been implemented, because funding was not appropriated, not fully allocated, or misallocated. A national prevention strategy (Shearer, 2010), developed by representatives of 20 federal agencies, provided a comprehensive agenda for prevention and recommended funding starting at $500 million and rising to $2 billion. However, it was never fully funded, and monies have been shifted for other purposes within the Department of Health and Human Services.

We discuss below specific policies or enhanced implementation of existing policies in the three vital directions. Although we frame recommendations in terms of the people who will benefit from them directly, family members may also benefit; for example, financial strain on parents or caregivers may be reduced by nutritional benefits provided to children. We emphasize programs that are likely to trigger beneficial spillovers and improve overall population health. Because disadvantaged and vulnerable people should benefit most from these policies, their enactment and implementation should also reduce health disparities.

Health Disparities and the Upstream Social Determinants of Health

Policies that improve the overall social and economic well-being of individuals and families will reverberate across a range of health outcomes and help to achieve health equity. Some examples follow.

Home-visiting programs in pregnancy and for parents of young children. Home-visiting programs, especially during pregnancy and early childhood, have demonstrated multiple benefits. Such programs as Healthy Families America, Nurse-Family Partnership, and Parents as Teachers address threats to social, emotional, and cognitive health in children of low-income families by assessing family needs, educating and supporting parents, and referring and coordinating services as needed. They can help parents and children to build better relationships, strengthen family support networks, and link families to community resources, although results have not been consistently strong across implementations (Olds, 2016). The strongest evidence is related to the Nurse-Family Partnership program, whose rigorous evaluations have shown better cognitive development, lower mortality from preventable causes, reduced arrest rates, reduced child abuse, and fewer days on food stamps (Office of the Surgeon General, 2001; Olds et al., 2002, 2004, 2014). The ACA expanded home visiting by amending Title V of the Social Security Act to create the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program, allocating $1.5 billion to states, territories, and tribes in FY2010–2015. Funding at $400 million per year was extended through September 2017. Support for evaluation of existing programs and programmatic innovations was built into the ACA mandate, and their effects on parenting behavior, child abuse and neglect, economic self-sufficiency, and child development are now being assessed.

Earned income tax credit. Nearly 30 million families receive earned income tax credit (EITC) benefits, which provide cash transfers to low- to moderate-income working people, particularly those who have children. The federal program costs roughly $70 billion a year and lifts about 9.4 million families above the poverty line (IRS, 2016). About 80% of eligible families receive EITC benefits. Rigorous studies indicate that more generous EITC benefits predict improvement in maternal health, improvements in indexes of both physical health (for example, blood pressure and inflammation markers) and mental health (Evans et al. 2010), reductions in maternal smoking during pregnancy, healthier birth outcomes, decreases in childhood behavioral problems, enriched home environments for children, and better mathematics and reading achievement scores (Dahl et al., 2005; Hamad and Rehkopf, 2015, 2016; Hoynes et al., 2012; Strully et al., 2010). Benefits vary substantially between states, because many states add to the federal benefit package; 12 states increase the federal benefit by 20% or more. States with higher benefit rates also enjoy better health returns, and this suggests that greater health could be achieved by increasing the federal benefits to match the more generous states. EITC benefits are quite low for childless workers, including noncustodial parents. Improving benefits for noncustodial parents in New York was associated with higher employment rates and child support payments (Nichols and Rothstein, 2015). Greater health benefits could be achieved by including more people, increasing the benefit rate, and providing higher benefits.

Federal minimum wage. The current federal minimum wage—$7.25 per hour—translates to $14,500 a year for a full-time employee and places a family of three far below the poverty line. Poverty is a strong predictor of poor health and earlier mortality not only of the worker but of family members. A 2001 modeling analysis of increasing the minimum wage to $11 per hour estimated substantial benefits for low-income families by decreasing the risk of premature death and reducing sick days, disability, and depression and for children in those families by increasing high school completion and reducing early childbirth (Bhatia and Katz, 2001). EITC and minimum-wage increases are complementary (Nichols and Rothstein, 2015).

Although some counties and states have passed laws to raise minimum wages to $15 per hour, smaller increases should still have an effect on health. One of the immediate effects may be a reduction in food insecurity. In contemporary, obesogenic environments, food insecurity is linked to consumption of calorie-rich but nutritionally poor foods and consequent weight gain, especially in girls and women (Burke et al., 2016; Cheung et al., 2015). State comparisons suggest that minimum-wage differences have contributed to about 10% of the increase in average body-mass index since 1970 (Meltzer and Chen, 2011). Legislation proposed in the 114th Congress to increase the federal minimum wage to $12 per hour by 2020, phased in by $1 per hour each year, would likely have health benefits, especially among low-income workers.

Occupational safety and health. Deaths of US workers on the job and from occupation-related diseases occur disproportionately among those who have limited labor-market opportunities and accept unsafe working conditions. These workers are commonly members of racial or ethnic minorities, immigrants, and people who have little education (Steege et al., 2014). The main agency charged with averting work-related injury and other harm is the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and substantial evidence indicates that OSHA enforcement activities reduce workplace injuries (Michaels, 2012; Tompa et al., 2016). Its capacity to ensure that all workers have safe conditions is impeded by the granting of exemptions to many employers and by inadequate funding for oversight. Employers that have 10 or fewer employees are not required by OSHA to keep injury and illness records unless specifically instructed, and enforcement of occupational-safety regulations on small farms that have paid employees is constrained. At current funding levels, OSHA has one compliance officer for every 59,000 workers and 3,600 worksites (OSHA, 2016). Additional capacity is needed to adequately meet OSHA’s current mandate, which should also be expanded to smaller employers and agricultural employees.

Episodes of unusual need throughout the life course. Policies that enable individuals and families to deal with challenging periods and life events may be especially effective. Beyond supporting home visiting during pregnancy and early childhood noted above, several types of policies may buffer job loss and address other temporary periods of family need:

- Expanding the Family Medical Leave Act to cover smaller employers, and add paid leave.

- Allowing family caregivers to be financially compensated for critical care, and reduce the long-term labor-market effect of family caregiving.

- Giving employers incentives to provide paid parental leave and paid sick leave, including for low-wage workers.

- Expanding unemployment insurance, especially for low-wage workers.

Most countries support time spent in caring for family members, and the availability of sick leave and parental leave is associated with better health. Across 141 countries, neonatal, infant, and child mortality is lower in those that offer longer paid maternal leave (Heymann et al., 2011). Children whose parents return sooner to work after birth have lower odds of being immunized against polio and measles (Berger et al., 2005). Dual-earner support policies in Nordic countries that provide child-care support and paid leave for both mothers and fathers are associated with lower poverty levels and infant mortality (Lundberg et al., 2008).

The United States is the only high-income country and one of only eight globally not requiring paid leave for mothers (Gault et al., 2014). The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 provided up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave a year to care for new children or seriously ill family members or, for a subset of employees, to recover from their own health conditions. However, an estimated 40% of the workforce is not covered by the Act, and many people cannot afford to take unpaid leave (National Partnership for Women and Families, 2016).

Adult family members also commonly require care during episodes of illness or age-related disability. An estimated 17% of Americans are providing care for adults, generally spouses or parents. Most caregivers are employed, and 60% report having to make a workplace accommodation for caregiving (Weber-Raley and Smith, 2015). Such caregiving is associated with stress and poor health outcomes in the caregivers (Adelman et al., 2014; Capistrant et al., 2011, 2012; Wolff et al., 2016). The growing vacuum of unmet needs calls for policies that ensure coverage for the role that family members increasingly have to play in caring for loved ones.

Vulnerability also comes with becoming unemployed. Unemployment is associated with cardiovascular disease, depression, substance use, and other health problems (Deb et al., 2011; Gallo et al., 2000). Adverse health effects are partially offset by unemployment insurance (Cylus et al., 2014, 2015). The US Department of Labor’s unemployment-insurance program provides unemployment benefits to eligible workers in conjunction with individual states’ policies. In most states, a worker can receive up to 26 weeks of about half the pay received in their most recent job (Stone and Chen, 2014). That is helpful, but many people do not qualify, benefits differ substantially among states, and those who fail to find a job during the 26-week period may be left without income or a safety net.

Criminal justice and sentencing policies. The US incarceration rate is higher than that of any other country and is five times greater than the worldwide median (Sentencing project, 2016). Well-documented adverse health effects of incarceration need attention, and longer-term consequences for incarcerated individuals, their families, and communities need to be characterized better to guide future reforms (NRC and IOM, 2013b). Particular attention to effects on youth involved with the justice system is needed:

- Improving prison health care services to reduce infectious-disease transmission and improve care management.

- Funding rigorous evaluation of programs to improve the health of people who are involved with the criminal justice system and their families, including alternative sentencing strategies, family preservation, and reentry programs.

- Strengthening diversion and mental health court pipelines for youth. Incorporate mental health services and women’s health services into the juvenile crime system.

Incarceration increases transmission of infectious disease, such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and viral hepatitis; these diseases are in turn transmitted to the communities after prisoners are released (Cloud et al., 2014; Drucker, 2013). Despite greater health needs, health care for the incarcerated is characterized by delays, restrictive prescription formularies, and inadequate availability of acute and specialty medical care, including women’s health care (Daniel, 2007; Drucker, 2013; Freudenberg and Heller 2016; Travis et al., 2014). Incarceration has ripple effects on families: as of 2007, black children were 7.5 times more likely and Hispanic children 2.5 times more likely than white children to have an incarcerated parent. Improving health care for incarcerated people is likely to be cost-effective and could have spillover benefits to their families and communities (Hammett, 2001).

Juvenile offenders have a higher risk of early and violent death than the general population, and this risk is especially high for black youth (Aalsma et al.,2016; Teplin et al., 2005). Incarcerated youth have greater health needs than their nonincarcerated peers (Prins, 2014), but health care services in the juvenile justice system are inadequate and lack enough mental health and substance abuse treatment professionals (Braverman and Murray, 2011). The health needs of incarcerated girls, including pregnancy-testing and prenatal services, are routinely unmet in a system that is designed primarily for boys (Braverman and Murray 2011). The National Research Council report Reforming Juvenile Justice: A Developmental Approach proposed a developmentally informed framework to treat youth fairly, hold them accountable, and prevent further offending (Bonnie et al., 2013).

Fostering Health – Promoting Behaviors and Diminishing Risk

To grow up healthy and remain healthy into old age, people need resources that enable healthy behaviors, reduce environmental risks, and improve their capacity to maximize their own health. Investment in early life can form the foundation for better health later and yield enduring benefits. However, since early gains can be undone by adverse environments encountered later in life, attention is needed at every life stage.

Nutrition assistance. Adequate nutrition from a healthy diet is necessary at all stages of life, but especially during pregnancy and in childhood, when growth is most rapid. Large-scale Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs (SNAPs) have been causally linked to greater consumption by children of fresh fruits and vegetables, 1% milk (a superior alternative to whole milk), and fewer sugar-sweetened beverages (Long et al., 2013). A temporary expansion of SNAP benefits in Massachusetts was linked to reductions in inpatient Medicaid expenditures, which suggests that conventional benefit levels are too low (Sonik, 2016). The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) targets pregnant women and postpartum mothers who have children 0–5 years old and combines vouchers that encourage consumption of lower-fat milk, fruits, vegetables, and whole grains; nutritional and health counseling, including promotion of breastfeeding; and referrals to health care and social-service providers. Participation in WIC has been associated with better birth outcomes and higher child-immunization rates. SNAP serves roughly 45 million households a month but is thought to miss about 17% of eligible participants. Expanded enrollment and greater attention to nutritional impact of benefits is needed.

Children’s cognitive and social skills. A child’s brain development can be impaired by exposure to adversity and lack of responsive, stimulating environments (Hertzman and Boyce, 2010). Children in low-income families are exposed to fewer words and less-affirming responses, and this results in a more constricted vocabulary and a relative disadvantage by the time they begin formal schooling (Hart and Risley, 2003). Children in such environments benefit from high-quality child care. For example, low-income children randomized to attend a preschool that combined a half-day session with family home visits showed long-term cognitive and social benefits; the program generated a financial return on investment in the form of savings on remedial education, incarceration, and teen pregnancies (Knudsen et al., 2006). The best available evidence indicates that high-quality early education programs have both social and health benefits (Campbell et al., 2014; Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2015; Duncan and Magnuson, 2013). However, although the programs set the stage for success, their gains can be undermined if children do not have access to good K–12 schooling. Racial and socioeconomic differences in school quality may thus translate into health disparities (Duncan and Murnane, 2014; Keating and Simonton, 2008).

The strongest current evidence on early education relies on a relatively small number of rigorously conducted studies. We lack sufficient evidence on how variations in program design may modify short-term and long-term effects. Programs and school improvements are likely to be phased in over time, allowing for experimentation and continued research to identify opportunities for improvements in program effectiveness and efficiency. Therefore, priorities should be placed on

- Expanding access to high-quality child care and preschool and promoting high-quality primary and secondary schools.

- Supporting research on the effects of child care and education programs on health and development.

Healthy behavior incentives. Health behaviors account for over one-third of premature deaths and are strongly influenced by socioeconomic factors (McGinnis et. al., 2002). Smoking, lack of exercise, and diet are among the most important known determinants of health. Market practices that encourage health-damaging behaviors call for offsetting policies that create disincentives to engage in them:

- Supporting FDA regulation to reduce the nicotine in cigarettes to below an addictive threshold.

- Encouraging the further adoption and rigorous evaluation of city and state taxes for tobacco and sugar-sweetened beverages with emphasis on using generated funds to support high-priority health programs and inform consideration of a federal tax.

- Encouraging city and state policies to use and evaluate cross-subsidies that increase the costs of foods high in fat, salt, or sugar and decrease costs of other foods in restaurants and grocery stores.

Policies and interventions that target use of combustible cigarettes have resulted in a marked drop in consumption over the last few decades. It is consistent with microeconomic theory that increasing the purchase price of cigarettes through added taxes substantially contributed to the marked decline in use and a later decrease in smoking-related diseases (Colchero et al., 2016). However, tobacco use remains an important contributor to premature mortality: nearly 17% of Americans smoke, and rates are higher among those who have lower income and education. Quitting is made harder by the fact that combustible cigarettes are designed with nicotine concentrations that engender physiologic addiction. Reduced-nicotine cigarettes facilitate smoking cessation (Donny et al., 2015). Greater gains in reducing smoking could be made if manufacturers reduced the amount of nicotine in cigarettes to a nonaddictive concentration (Fiore, 2016).

Food marketers, including restaurants, grocery stores, bodegas, and food companies, similarly influence consumption patterns. Some of their actions are contributing to overconsumption and overweight and increasing the risks of diabetes and other chronic conditions (Bartlett et al., 2014). Off-setting actions include making healthier options more salient, easier to access, and less expensive and promoting their selection as a default. Small demonstration programs suggest that increasing the cost of sugar-sweetened beverages could reduce overweight and obesity. Berkeley, California, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, are using funds generated by increasing taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages to fund other high-priority health programs (such as universal preschools). One concern is that such a tax is potentially regressive in creating a greater economic burden on low-income consumers. However, the counterargument is that the resulting disincentive would be particularly beneficial to that population by reducing its consumption of a health-damaging product and that it would benefit disproportionately from the services enabled by the revenues.

Firearm safety. Injuries from firearms are an important and preventable source of health disparities, especially for youth and young adults, for whom gun incidents are the second-leading cause of death. Homicides are visible and garner attention, but firearm suicides are nearly twice as common as firearm homicides—21,175 versus 11,208 in 2013 (Xu et al., 2016). Their occurrence in the United States is six times greater than the average in 23 other high income OECD countries (Richardson and Hemenway, 2011). In addition, accidental discharges of firearms cause about 500 deaths a year, including deaths involving guns picked up by very young children.

Firearm injury is a public health concern and should be dealt with accordingly. More than is the case with any other health issue, developing and testing effective programs and policies to reduce firearm-related morbidity and mortality are hampered both by a paucity of relevant data and the lack of a coordinated approach to regulation of what is a dangerous consumer product.

Most Americans want such strategies as universal background checks and assault-weapons bans (Gallup Surveys, 2016), which could reduce injuries and deaths without curtailing legitimate uses of firearms. Background checks would not only reduce homicides (Rudolph et al., 2015) but lower the number of completed suicides inasmuch as such acts are often impulsive and may be averted owing to the time needed for the background check (Miller and Hemenway, 2008). Firearm manufacturers are not subject to the same design standards as are imposed on other consumer products; such standards could reduce the risk of unintentional harm and the use of firearms against others, including law-enforcement personnel.

Pressing firearm safety priorities include

- Creating a national research infrastructure that includes sustained funding of the National Violent Death Reporting System to enable more research on public health approaches to promoting gun safety.

- Requiring permits, comprehensive background checks, and waiting periods for firearm sales, and require firearms dealers to implement them.

- Encouraging application of federal health and safety oversight to firearm design similar to that involving other dangerous consumer products.

Health Care Financing Strategies to Reduce Health Disparities

The traditional models for financing medical care in the United States deliver less than optimal population health, allow substantial health disparities, and exacerbate the burgeoning cost of medical care. Expenditures on clinical care have an opportunity cost, and the amount of money devoted to health care delivery makes it difficult to provide sufficient support for other kinds of investment that would have greater health benefits. The US medical care system emphasizes treating illness over preventing disease; this is the case for mental health and substance abuse disorders as well as for physical diseases (Frank and Glied, 2006). Large sums are spent when people are acutely ill; much less is spent to prevent illness or manage chronic disease. Economic incentives underlie the discrepancy (Cutler, 2014). Both public and private payers for medical care generally reimburse physicians on a fee-for-service basis, and payment is based on the volume and intensity of services provided. More acute services are reimbursed better than less acute ones; this reflects in part a natural desire to provide help to those in crisis. This financing structure results in extensive care provision in acute settings, insufficient care in less intense situations, and inattention to social causes of disease. Steps that can be taken to rectify that imbalance would improve overall population health and reduce disparities.

Several new initiatives have the potential to increase access to care, reduce the cost of care to free resources for public health priorities, and improve the quality of care. The ACA provides opportunities to link efforts in the clinic with those in the community. As part of moving from a volume-based health system to a value-based health system, current demonstration projects funded by the Department of Health and Human Services are examining whether and how integration of public health activities with clinical care systems can improve population health, enhance quality, and lower costs. Team-based approaches to patient-centered care and prevention are receiving heightened attention. Community-based demonstration projects, such as State Innovation Models and Accountable Health Communities, offer special opportunities to establish such linkages and address social determinants of health.

Alternative payment models. Two commonly proposed alternative payment mechanisms deviate from the predominant fee-for-service reimbursement model. The first is the pay-for-performance system, in which higher-quality care is reimbursed more than lower quality care. For example, for a person who has a chronic health problem, the traditional fee-for-service reimbursement model pays the primary care physician or specialist for each visit, whether or not it adequately addresses the patient’s needs. In a pay-for-performance system, quality is based on the proportion of a provider’s patients with the illness who are receiving appropriate therapy, and on how many acute episodes are prevented. Physicians who adhere to guideline recommendations better and have fewer acute incidents among their patients receive financial bonuses.

A second alternative payment model is a bundled payment or global-payment system in which a fixed amount is paid for each patient, depending on the patient’s diagnosis and disease severity, regardless of what services are provided. The clinician is responsible for all the costs of care management. For example, a physician who successfully works with a patient to take needed medications and avoids inpatient care would keep the savings from prevented hospitalizations. Bundled payment models generally provide bonus payments for higher quality of care.

Payment mechanisms that value prevention over acute care should encourage providers to address social factors that drive the need for services. However, ill-planned implementation of such policies could backfire if incentives discourage caring for vulnerable populations. Quantifying the costs associated with their care is an important challenge in both bundled-payment and pay-for-performance models (NASEM, 2016; Sills et al., 2016). If extra costs associated with caring for impoverished or socially marginalized patient groups are not fully captured in metrics of patient illness (such as number of comorbid conditions), the resulting inadequate adjustment in calculating reimbursement structures could foster discrimination by care providers and financially handicap safety-net providers.

Recent pay-for-performance and bundled-payment experiments have had encouraging results (Cutler, 2015). Pay-for-performance systems have been associated with increased care quality but less cost savings. Bundled-payment systems are associated with both quality improvements and cost savings (Nyweide et al., 2015; Rajkumar et al., 2014; Swchwartz et al., 2015; Song et al., 2014).The Department of Health and Human Services has proposed expanding the use of alternative payment structures in Medicare with a goal of 30% of Medicare payments on an alternative-payment basis by 2016 and 50% by 2018 and most of the other payments tied to quality. However, more remains to be done to expand the programs, including involvement of private payers, and appropriate targets should be set to accelerate movement to alternative payment models.

Health insurance coverage. People who do not have health insurance receive less care than those who do have health insurance, including preventive care and screening (Baicker et al., 2013; Sommers et al., 2014), and their health may suffer as a result. In 2014, about 33 million Americans were uninsured for at least part of the year. The ACA improved health care access substantially by establishing health-insurance exchanges, although enrollment in exchanges varies by state. Universal access to Medicaid was intended for people who had incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty line, and subsidies for health insurance for those who had incomes of 138–400% of the poverty line. However, the Supreme Court ruling in NFIB v. Sebelius allowed states to opt out of the Medicaid expansion, and about 3 million potentially eligible people live in states that opted out. Nevertheless, about 20 million people have obtained coverage under the ACA. Efforts needed to meet the nation’s intent to ensure coverage include

- Encouraging states to opt into the Medicaid expansion.

- Determining which areas have relatively low enrollment in health-insurance exchanges and target enrollment efforts in these areas.

Chronic disease and oral health. More comprehensive health care coverage contributes to better health. When coverage is narrower, people use fewer services, and quality of care suffers (Brot-Goldberg et al., 2015; Lohr et al., 1986). The ACA limited the cost-sharing that can be required in insurance, but the minimum policies are not particularly generous, and greater coverage is needed to enable better care for chronic disease.

Many people suffer from chronic illnesses (such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and mental illness) that often can be treated with relatively inexpensive pharmaceuticals, but high cost-sharing may inhibit their use. For example, each $10 increase in monthly cost-sharing reduces use of chronic-care medications by about 5% (Goldman et al., 2007). The ACA requires insurers to cover, with no cost-sharing, preventive services that are shown to be effective. That principle can be extended to chronic-disease management, starting with therapies that are inexpensive and highly effective.

The services covered by the policies should include dental care (Donoff et al., 2014). Oral health problems, such as inflammation of the gums, can trigger or exacerbate other health problems, such as heart disease, pulmonary disease, and poor perinatal health (HHS, 2000). Health insurance generally omits access to all but emergency dental services and provides less access to dental care than to medical care. Beyond possible overall costs savings from an investment in oral health (Jeffcoat et al., 2014), better oral health is important in its own right and may even have spillover effects on socioeconomic outcomes (Glied and Neidell, 2010). ACA expanded dental coverage for children but not for adults.

Pressing priorities therefore include

- Requiring Medicare Part D and exchange health plans to cover chronic-disease care that leading bodies certify is highly effective, that has only modest cost, and whose cost is a barrier to using the service.

- Expanding Medicare, Medicaid, and exchange health plans to cover dental care.

- Expanding standards for primary care medical homes and other advanced primary care practice designs to allow adequate access to and use of preventive dental care.

Conclusion

The emphasis in our health system on medical treatments for acute problems has yielded benefits for some but has failed to achieve the levels of population health and longevity enjoyed by other nations. Overcoming our national health disadvantage will require rebalancing our priorities to focus more on preventing or ameliorating health-damaging social conditions and behavioral choices. It is an issue not of how much money is invested in health but of whether the dollars are spent on factors that provide the greatest benefit. Moreover, a number of policies addressing social and behavioral determinants of health would entail little or no additional cost. This paper has presented only a sample of the wide array of policy options that address social and behavioral determinants of health. Such policies typically are not viewed as “health policies” but, in fact, have great potential to reduce health disparities and improve the health and longevity of all Americans.

References

- Aalsma, M. C., K. S. Lau, A. J. Perkins, K. Schwartz, W. Tu, S. E. Wiehe, P. Monahan, and M. B. Rosenman. 2016. Mortality of youth offenders along a continuum of justice system involvement. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 50(3):303-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.030

- Adelman, R. D., L. L. Tmanova, D. Delgado, S. Dion, and M. S. Lachs. 2014. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA 311(10):1052-1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.304

- Adler, N. E., and D. H. Rehkopf. 2008. US disparities in health: Descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annual Review of Public Health 29:235-252. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852

- Almond, D., K. Y. Chay, and M. Greenstone. 2006. Civil Rights, the War on Poverty, and Black-White Convergence in Infant Mortality in the Rural South and Mississippi. MIT Department of Economics Working Paper 07-04. Available at: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/63330 (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Arias, E. 2015. United States life tables, 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports 64. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_11.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Avendano, M., M. M. Glymour, J. Banks, and J. P. Mackenbach. 2009. Health disadvantage in US adults aged 50 to 74 years: A comparison of the health of rich and poor Americans with that of Europeans. American Journal of Public Health 99(3):540-548. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.139469

- Baicker, K., S. L. Taubman, H. L. Allen, M. Bernstein, J. H. Gruber, J. P. Newhouse, E. C. Schneider, B. J. Wright, A. M. Zaslavsky, and A. N. Finkelstein. 2013. The Oregon experiment—effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine 368(18):1713-1722. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1212321

- Bartlett, S., J. Klerman, P. Wilde, L. Olsho, C. Logan, M. Blocklin, M. Beauregard, and A. Enver. 2014. Evaluation of the Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP) Final Report. Washington, DC: USDA. Available at: https://mafoodsystem.org/media/resources/pdfs/PilotFinalReport.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Berger, L. M., J. Hill, and J. Waldfogel. 2005. Maternity leave, early maternal employment and child health and development in the US. Economic Journal 115(501):F29-F47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-0133.2005.00971.x

- Bhatia, R., and M. Katz. 2001. Estimation of health benefits from a local living wage ordinance. American Journal of Public Health 91(9):1398-1402. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.9.1398

- National Research Council. 2013. Reforming Juvenile Justice: A Developmental Approach. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/14685

- Bradley, E., and L. Taylor. 2013. The American health care paradox: Why spending more is getting us less. New York: Public Affairs.

- Bradley, E. H., B. R. Elkins, J. Herrin, and B. Elbel. 2011. Health and social services expenditures: Associations with health outcomes. BMJ Quality and Safety. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.048363

- Braverman, P., and P. Murray. 2011. Health care for youth in the juvenile justice system. Pediatrics 128(6):1219-1235. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1757

- Brot-Goldberg, Z. C., A. Chandra, B. R. Handel, and J. T. Kolstad. 2015. What Does a Deductible Do? The Impact of Cost-Sharing on Health Care Prices, Quantities, and Spending Dynamics. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 21632. Available at: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/nbrnberwo/21632.htm (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Burke, M. P., E. A. Frongillo, S. J. Jones, B. B. Bell, and H. Hartline-Grafton. 2016. Household food insecurity is associated with greater growth in body mass index among female children from kindergarten through eighth grade. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 11(2):227-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2015.1112756

- Campbell, F., G. Conti, J. J. Heckman, S. H. Moon, R. Pinto, E. Pungello, and Y. Pan. 2014. Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science 343(6178):1478-1485. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1248429

- Capistrant, B., J. Moon, L. Berkman, and M. Glymour. 2011. Current and long-term spousal caregiving and onset of cardiovascular disease. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 66(10):951-956. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200040

- Capistrant, B. D., J. R. Moon, and M. M. Glymour. 2012. Spousal caregiving and incident hypertension. American Journal of Hypertension 25(4):437-443. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajh.2011.232

- Case, A., and A. Deaton. 2015. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112(49):15078-15083. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1518393112

- Chetty, R., M. Stepner, S. Abraham, S. Lin, B. Scuderi, N. Turner, A. Bergeron, and D. Cutler. 2016. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA 315(16):1750-1766. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.4226

- Cheung, H. C., A. Shen, S. Oo, H. Tilahun, M. J. Cohen, and S. A. Berkowitz. 2015. Peer-reviewed: Food insecurity and body mass index: A longitudinal mixed methods study, Chelsea, Massachusetts, 2009–2013. Preventing Chronic Disease 12:E125. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2015/15_0001.htm (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Cloud, D. H., J. Parsons, and A. Delany-Brumsey. 2014. Addressing mass incarceration: A clarion call for public health. American Journal of Public Health 104(3):389-391. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301741

- Colchero, M. A., B. M. Popkin, J. A. Rivera, and S. W. Ng. 2016. Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages: Observational study. BMJ 352:h6704. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6704

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. 2015. Promoting health equity through education programs and policies: Center-based early childhood education. Guide to Community Preventive Services. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/healthequity/education/centerbasedprograms.html (accessed May 11, 2016).

- Currie, J., and H. Schwandt. 2016. Inequality in mortality decreased among the young while increasing for older adults, 1990–2010. Science 6;352(6286). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf1437

- Cutler, D. M. 2014. The quality cure. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Cutler, D. M. 2015. Payment reform is about to become a reality. JAMA 313(16):1606-1607. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.1926

- Cylus, J., M. M. Glymour, and M. Avendano. 2014. Do generous unemployment benefit programs reduce suicide rates? A state fixed-effect analysis covering 1968-2008. American Journal of Epidemiology 180(1):45-52. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwu106

- Cylus, J., M. M. Glymour, and M. Avendano. 2015. Health effects of unemployment benefit program generosity. American Journal of Public Health 105(2):317-323. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302253

- Dahl, G. B., L. Lochner, and National Bureau of Economic Research. 2005. The Impact of Family Income on Child Achievement. NBER Working Paper 11279. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at: https://econweb.ucsd.edu/~gdahl/papers/children-and-EITC.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Daniel, A. E. 2007. Care of the mentally ill in prisons: Challenges and solutions. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 35(4):406-410. Available at: http://jaapl.org/content/35/4/406 (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Deb, P., W. T. Gallo, P. Ayyagari, J. M. Fletcher, and J. L. Sindelar. 2011. The effect of job loss on overweight and drinking. Journal of Health Economics 30(2):317-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.12.009

- Donny, E. C., R. L. Denlinger, J. W. Tidey, J. S. Koopmeiners, N. L. Benowitz, R. G. Vandrey, M. al’Absi, S. G. Carmella, P. M. Cinciripini, S. S. Dermody, D. J. Drobes, S. S. Hecht, J. Jensen, T. Lane, C. T. Le, F. J. McClernon, I. D. Montoya, S. E. Murphy, J. D. Robinson, M. L. Stitzer, A. A. Strasser, H. Tindle, and D. K. Hatsukami. 2015. Randomized trial of reduced-nicotine standards for cigarettes. New England Journal of Medicine 373(14):1340-1349. Available at: https://www.vumc.org/v-create/publication/randomized-trial-reduced-nicotine-standards-cigarettes (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Donoff, B., J. E. McDonough, and C. A. Riedy. 2014. Integrating oral and general health care. New England Journal of Medicine 371(24):2247. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1410824

- Drucker, E. 2013. A plague of prisons: The epidemiology of mass incarceration in America. New York: The New Press.

- Duncan, G. J., and K. Magnuson. 2013. Investing in preschool programs. Journal of Economic Perspectives 27(2):109. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.27.2.109

- Duncan, G. J., and R. J. Murnane. 2014. Restoring opportunity: The crisis of inequality and the challenge for American education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Evans, W. N., C. L. Garthwaite, and National Bureau of Economic Research. 2010. Giving Mom a Break: The Impact of Higher EITC Payments on Maternal Health. NBER working Paper 16296. Cambridge, MA: National

Bureau of Economic Research. Available at: https://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/faculty/garthwaite/htm/Evans_Garthwaite_EITC.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020). - Fiore, M. C. 2016. Tobacco control in the Obama era: Substantial progress, remaining challenges. New England Journal of Medicine 375:1410-1412. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607850

- Frank, R. G., and S. A. Glied. 2006. Better but not well: Mental health policy in the United States since 1950. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Freudenberg, N., and D. Heller. 2016. A review of opportunities to improve the health of people involved in the criminal justice system in the United States. Annual Review of Public Health 37(1):313-333. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021420

- Gallo, W. T., E. H. Bradley, M. Siegel, and S. V. Kasl. 2000. Health effects of involuntary job loss among older workers: Findings from the health and retirement survey. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 55(3):S131-S140. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/55.3.s131

- Gallup Surveys. 2016. Gallup guns. Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/1645/guns.aspx (accessed August 11, 2016).

- Gault, B., H. Hartmann, A. Hegewisch, J. Milli, and L. Reichlin. 2014. Paid Parental Leave in the United States: What the Data Tell Us About Access, Usage, and Economic and Health Benefits. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Available at: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2608&context=key_workplace (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Gelman, A., and J. Auerbach. 2015. Age-aggregation bias in mortality trends. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113(7):E816-E817. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523465113

- Glied, S., and M. Neidell. 2010. The economic value of teeth. Journal of Human Resources 45(2):468-496. Available at: http://jhr.uwpress.org/content/45/2/468.abstract (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Goldman, D. P., G. F. Joyce, and Y. Zheng. 2007. Prescription drug cost sharing: Associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA 298(1):61-69. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.1.61

- Hamad, R., and D. H. Rehkopf. 2015. Poverty, pregnancy, and birth outcomes: A study of the earned income tax credit. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 29(5):444-452. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12211

- Hamad, R., and D. H. Rehkopf. 2016. Poverty and child development: A longitudinal study of the impact of the earned income tax credit. American Journal of Epidemiology 183(9):775-784. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv317

- Hammett, T. M. 2001. Making the case for health interventions in correctional facilities. Journal of Urban Health 78(2):236-240. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.2.236

- Hart, B., and T. R. Risley. 2003. The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by age 3. American Educator 27(1):4-9. Available at: https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/TheEarlyCatastrophe.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Hertzman, C., and T. Boyce. 2010. How experience gets under the skin to create gradients in developmental health. Annual Review of Public Health 31:329-347. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103538

- Heymann, J., A. Raub, and A. Earle. 2011. Creating and using new data sources to analyze the relationship between social policy and global health: The case of maternal leave. Public Health Reports 126:127-134. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549111260S317

- Hoynes, Hilary, Doug Miller, and David Simon. 2015. Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7 (1): 172-211. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20120179

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS). 2016. About EITC. Available at: https://www.eitc.irs.gov/EITC-Central/abouteitc (accessed September 19, 2016).

- Jeffcoat, M. K., R. L. Jeffcoat, P. A. Gladowski, J. B. Bramson, and J. J. Blum. 2014. Impact of periodontal therapy on general health: Evidence from insurance data for five systemic conditions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 47(2):166-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.001

- Kaplan, G. A., N. Ranjit, and S. Burgard. 2008. Lifting gates, lengthening lives: Did civil rights policies improve the health of African American women in the 1960s and 1970s? Pp. 145-169 in Making Americans healthier: Social and economic policy as health policy. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Available at: http://www.npc.umich.edu/publications/workingpaper06/paper25/working_paper06-25.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Keating, D., and S. Simonton. 2008. Health effects of human development policies. Pp. 61-94 in Making Americans healthier: Social and economic policy as health policy, edited by G. A. Kaplan, J. S. House, R. F. Schoeni, and H. A. Pollack. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Knudsen, E. I., J. J. Heckman, J. L. Cameron, and J. P. Shonkoff. 2006. Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

of the United States of America 103(27):10155-10162. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0600888103 - Krieger, N., D. H. Rehkopf, J. T. Chen, P. D. Waterman, E. Marcelli, and M. Kennedy. 2008. The fall and rise of US inequities in premature mortality: 1960–2002. PLoS Medicine 5(2):e46. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050046

- Laing, Y., and M. Katz. 2012. Coronary arteries, myocardial infarction, and history. New England Journal of Medicine 366(13):1258-1260. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1201171

- Lasser, K. E., D. U. Himmelstein, and S. Woolhandler. 2006. Access to care, health status, and health disparities in the United States and Canada: Results of a cross-national population-based survey. American Journal of Public Health 96(7):1300-1307. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.059402

- Lohr, K. N., R. H. Brook, C. J. Kamberg, G. A. Goldberg, A. Leibowitz, J. Keesey, D. Reboussin, and J. P. Newhouse. 1986. Use of medical care in the Rand Health Insurance Experiment: Diagnosis- and service-specific

analyses in a randomized controlled trial. Medical Care 24(9):S1-S87. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3093785/ (accessed July 28, 2020). - Long, V., S. Cates, J. Blitstein, K. Deehy, P. Williams, R. Morgan, J. Fantacone, K. Kosa, L. Bell, and J. Hersey. 2013. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education and Evaluation Study (Wave II). Prepared

by Altarum Institute for the US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Available at: https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/SNAPEdWaveII.pdf (accessed July 28, 2020). - Lundberg, O., M. A. Yngwe, M. K. Stjarne, J. I. Elstad, T. Ferrarini, O. Kangas, T. Norstrom, J. Palme, and J. Frit¬zell. 2008. The role of welfare state principles and generosity in social policy programmes for public

health: An international comparative study. Lancet 372(9650):1633-1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61686-4 - McGinnis, J. M., P. Williams-Russo, and J. R. Knickman. 2002. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Affairs 21(2):78-93. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.78

- Meltzer, D. O., and Z. Chen. 2011. The impact of minimum wage rates on body weight in the United States. Pp. 17-34 in Economic aspects of obesity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Michaels, D. 2012. OSHA does not kill jobs; it helps prevent jobs from killing workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 55:961-963. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22122

- Miller, M., and D. Hemenway. 2008. Guns and suicide in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 359(10):989-991. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0805923

- Murphy, S., K. Kochanek, J. Xu, and E. Arias. 2015. Mortality in the United States, 2014. NCHS Data Brief 229.

- Nabel, E. G., and E. Braunwald. 2012. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine 366(1):54-63. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1112570

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Accounting for Social Risk Factors in Medicare Payment: Criteria, Factors, and Methods. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/23513

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2015. Health, United States, 2015—Individual Charts and Tables: Spreadsheet, PDF, and PowerPoint files, Table 14. Available at: http://www.cdc. gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf#014 (accessed April 30, 2016).

- National Partnership for Women and Families. 2016. Family and Medical Leave Act. Available at: http://www.nationalpartnership.org/issues/work-family/fmla.html (accessed September 19, 2016).

- Nichols, A., and J. Rothstein. 2015. The earned income tax credit. In Economics of means-tested transfer programs in the United States, volume 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2013. U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13497

- NRC and IOM. 2013b. Health and incarceration: A workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18372

- Nyweide, D. J., W. Lee, T. T. Cuerdon, H. H. Pham, M. Cox, R. Rajkumar, and P. H. Conway. 2015. Association of pioneer accountable care organizations vs traditional Medicare fee for service with spending, utilization, and patient experience. JAMA 313(21):2152-2161. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.4930

- Office of the Surgeon General. 2001. Youth violence: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD, Office of the Surgeon General, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, National Institute of Mental Health, and Center for Mental Health Services.

- Olds, D. 2016. Building evidence to improve maternal and child health. Lancet 387(10014):105-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00476-6

- Olds, D., H. Kitzman, R. Clole, J. Robinson, K. Sidora, D. W. Luckey, C. R. Henderson, C. Hanks, J. Bondy, and J. Holmberg. 2004. Effect of nurse home-visiting on maternal life course and child development: Age 6

follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics 114:1550-1559. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0962 - Olds, D. L., J. Robinson, R. O’Brien, D. W. Luckey, L. M. Pettitt, C. R. Henderson, Jr., R. K. Ng, K. L. Sheff, J. Korfmacher, S. Hiatt, and A. Talmi. 2002. Home visiting by paraprofessionals and by nurses: A randomized,

controlled trial. Pediatrics 110(3):486-496. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.110.3.486 - Olds, D. L., H. Kitzman, M. D. Knudtson, E. Anson, J. A. Smith, and R. Cole. 2014. Effect of home visiting by nurses on maternal and child mortality: Results of a 2-decade follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics 168(9):800-806. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.472

- Olshansky, S. J., D. J. Passaro, R. C. Hershow, J. Layden, B. A. Carnes, J. Brody, L. Hayflick, R. N. Butler, D. B. Allison, and D. S. Ludwig. 2005. A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. New England Journal of Medicine 352(11):1138-1145. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr043743

- OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration). 2016. OSHA Commonly Used Statistics. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/oshstats/commonstats.html (accessed August 21, 2016).

- Prins, S. J. 2014. Prevalence of mental illnesses in US state prisons: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services 65(7):862-872. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300166

- Rajkumar, R., P. H. Conway, and M. Tavenner. 2014. CMS—engaging multiple payers in payment reform. JAMA 311(19): 1967-1968. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.3703

- Richardson, E. G., and D. Hemenway. 2011. Homicide, suicide, and unintentional firearm fatality: Comparing the United States with other high-income countries, 2003. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery

70(1):238-243. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3181dbaddf - Rudolph, K. E., E. A. Stuart, J. S. Vernick, and D. W. Webster. 2015. Association between Connecticut’s permit-to-purchase handgun law and homicides. American Journal of Public Health 105(8):e49-e54. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302703

- Schwartz, A. L., M. E. Chernew, B. E. Landon, and J. M. McWilliams. 2015. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare Pioneer Accountable Care Organization program. JAMA Internal Medicine 175(11):1815-1825. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4525

- Shearer, G. 2010. Prevention provisions in the Affordable Care Act. American Public Health Association Issue Brief.

- Siddiqi, A., R. Brown, Q. C. Nguyen, R. Loopstra, and I. Kawachi. 2015. Cross-national comparison of socioeconomic inequalities in obesity in the United States and Canada. International Journal for Equity in Health

14(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0251-2 - Sills, M. R., M. Hall, J. D. Colvin, M. L. Macy, G. J. Cutler, J. L. Bettenhausen, R. B. Morse, K. A. Auger, J. L. Raphael, L. M. Gottlieb, E. S. Fieldston, and S. S. Shah. 2016. Association of social determinants with children’s

hospitals’ preventable readmissions performance. JAMA Pediatrics 170(4):350-358. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4440 - Sommers, B. D., S. K. Long, and K. Baicker. 2014. Changes in mortality after Massachusetts health care reform: A quasi-experimental study. Annals of Internal Medicine 160(9):585-593. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-2275

- Song, Z., S. Rose, D. G. Safran, B. E. Landon, M. P. Day, and M. E. Chernew. 2014. Changes in health care spending and quality 4 years into global payment. New England Journal of Medicine 371(18):1704-1714. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1404026

- Sonik, R. A. 2016. Massachusetts inpatient Medicaid cost response to increased Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits. American Journal of Public Health 106(3):443-448. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302990

- Steege, A. L., S. L. Baron, S. M. Marsh, C. C. Menéndez, and J. R. Myers. 2014. Examining occupational health and safety disparities using national data: A cause for continuing concern. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 57(5):527-538. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22297

- Stone, C. and W. Chen. 2014. Introduction to Unemployment Insurance. Available at: http://www.cbpp.org/research/introduction-to-unemployment-insurance (accessed September 19, 2016).

- Strully, K. W., D. H. Rehkopf, and Z. Xuan. 2010. Effects of prenatal poverty on infant health: State earned income tax credits and birth weight. American Sociological Review 75(4):534-562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122410374086

- Tarone, R., and J. McLaughlin. 2012. Coronary arteries, myocardial infarction, and history. New England Journal of Medicine 366(13):1258-1260. Available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMc1201171 (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Teplin, L. A., G. M. McClelland, K. M. Abram, and D. Mileusnic. 2005. Early violent death among delinquent youth: A prospective longitudinal study. Pediatrics 115(6):1586-1593. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1459

- The Sentencing Project. 2016. Criminal Justice Facts. Available at: http://www.sentencingproject.org/criminal-justicefacts/ (accessed September 19, 2016).

- Tompa, E., C. Kalcevich, M. Foley, C. McLeod, S. Hogg‐Johnson, K. Cullen, E. MacEachen, Q. Mahood, and E. Irvin. 2016. A systematic literature review of the effectiveness of occupational health and safety regulatory enforcement. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 59(11):919-933. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22605

- National Research Council. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18613

- US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 2000. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2016. HHS.gov Health Care. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/ (accessed May 15, 2016).

- van Hedel, K., M. Avendano, L. F. Berkman, M. Bopp, P. Deboosere, O. Lundberg, P. Martikainen, G. Menvielle, F. J. van Lenthe, and J. P. Mackenbach. 2014. The contribution of national disparities to international differences in mortality between the United States and 7 European countries. American Journal of Public Health 105(4):e112-e119. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302344

- Weber-Raley, L., and E. Smith. 2015. Caregiving in the U.S.: 2015 Report. National Alliance for Caregiving and the AARP Public Policy Institute.

- Wolff, J. L., B. C. Spillman, V. A. Freedman, and J. D. Kasper. 2016. A national profile of family and unpaid caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Internal Medicine 176(3):372-379. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7664

- Woolf, S. H., and L. Y. Aron. 2013. The US health disadvantage relative to other high-income countries: Findings from a National Research Council/Institute of Medicine report. JAMA 309(8):771-772. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.91

- Xu, J., S. Murphy, K. Kochanek, and B. Bastian. 2016. Deaths: Final data for 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports 64(2). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.