Addressing Burnout, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in the Osteopathic Profession: An Approach That Spans the Physician Life Cycle

TW: suicide

Introduction

Burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation are key areas of concern because of the consequences they can have on physicians as well as the patients for whom they care (Shanafelt et al., 2012; West et al., 2016). The level of burnout in the medical profession has increased at an alarming rate in the past decade. Statistics reveal that about 54 percent of all physicians are burnt out (30–40 percent of employed physicians and 55–60 percent of self-employed physicians) (Shanafelt et al., 2012, 2015). Students, interns, and residents also factor into the equation as reports indicate they experience burnout at a rate of 20–40 percent (Lapinski et al., 2016). According to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), burnout is defined as “a state of vital exhaustion” (WHO, 1992). It manifests as emotional exhaustion that affects a person’s passion for work; ability to relate to others; sense of accomplishment or purpose; judgment; productivity; emotions; and overall health (Shanafelt et al., 2012).

Depression is an illness that is characterized by signs and symptoms that can affect a person’s emotions, thoughts, and actions. Similar to burnout, depression has increased in the medical profession. It is most commonly studied in medical students and residents (Downs et al., 2014; Mata et al., 2015). The prevalence of depression among resident physicians is approximately 29 percent (Mata et al., 2015).

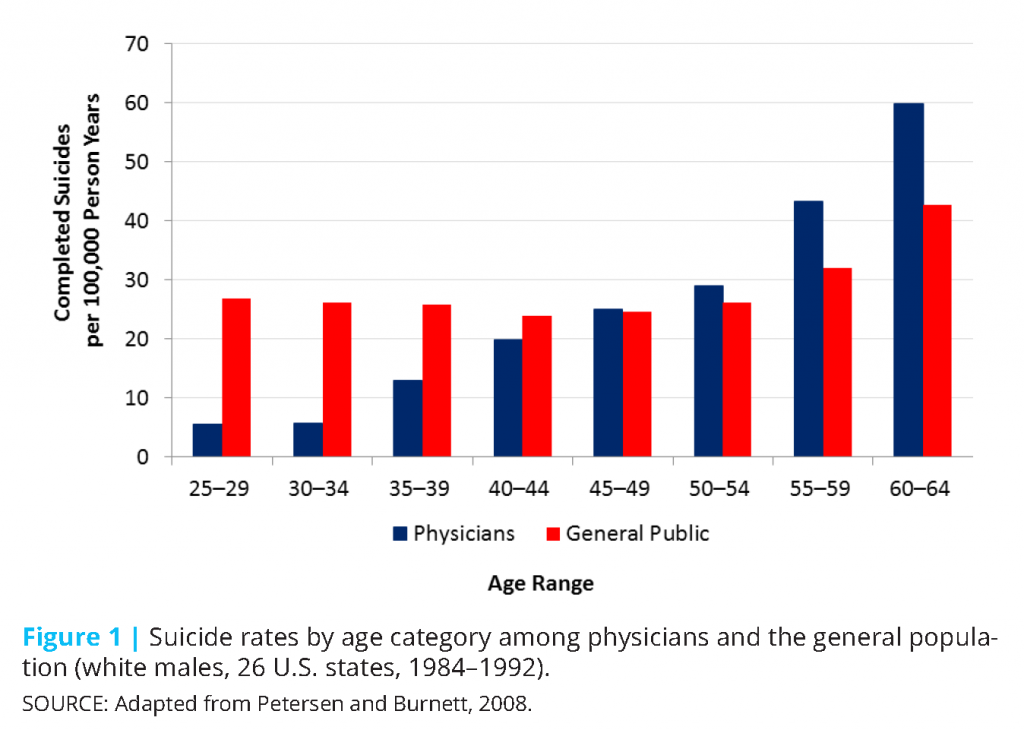

Suicidal ideation is an alteration of one’s thought process in which ending his or her life is the preferred avenue to seeking other options to cope with stressors at the time. Approximately 300–400 physicians commit suicide every year (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 2017; Andrew, 2015). Figure 1 illustrates the incidence in suicide among white male physicians, but more importantly, it highlights that suicidal ideation is not merely an issue for students and residents, but is also a concern across a physician’s life cycle—and an even higher concern among physicians toward the end of their careers (Petersen and Burnett, 2008).

Together, burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation (or simply, physician wellness) are multifactorial issues that include physicians’ socioeconomic strains and presumptive factors of lifestyle, loss of autonomy in the workplace, and ever-changing demands of regulations (Privitera et al., 2015). These factors can pose a heavy burden on physicians at different stages of their careers (e.g., student, resident, practicing physician, and retired physician).

The Osteopathic Physician: Who We Are and What We Do

At the core of osteopathic medicine [1] is a holistic approach. Andrew Taylor Still, the founder of this approach, was a strong proponent of mental health. This focus is evident in the osteopathic tenets that focus on the interrelatedness of the body, mind, and spirit (AOA, 2017). More specifically, the tenets state the following:

- The body is a unit; the person is a unit of body, mind, and spirit.

- The body is capable of self-regulation, self-healing, and health maintenance.

- Structure and function are reciprocally interrelated.

- Rational treatment is based on an understanding of the basic principles of body unity, self-regulation, and the interrelationship of structure and function

It is contended that the treatment of symptoms does not mean the cause has been addressed (Still, 1902). It is important to identify the underlying cause for the presenting problem. Thus, the osteopathic approach to care requires the consideration of every aspect of the patient (mind, body, and soul—physical, social, mental, and emotional).

Osteopathic medical students and residents are trained to incorporate these principles into their clinical approach. Typically, there is a focus on the second and third tenets because of the application of osteopathic manipulative medicine/osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMM/OMT). Irrespective of how the tenets are incorporated into osteopathic physicians’ clinical approach and care for patients, training rarely includes looking at these tenets as they apply to the practitioner. Thus, in order to address physician wellness, the osteopathic profession must recognize the increase in burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation is the symptom, and the cause is yet to be fully understood and treated. As elucidated in Still’s writings, the osteopathic approach to addressing these health issues requires an understanding about the individual nature of a student’s/physician’s presentation, and appreciating no one approach fits all.

The Dilemma and Its Influence on Wellness

Physicians see themselves as healers; they “fix” people who are broken. For themselves, however, physicians appear to adopt the age-old phrase, “Physician heal thyself.” This attitude perpetuates itself in the history of nondisclosure in medicine and results in students and physicians alike failing to seek the help needed even when it is readily available (Andrew, 2015; Gold et al., 2013). Additionally, there is a perception that seeking help or acknowledging one’s shortcoming is a weakness. Coupling this attitude with the stigma of mental health, it is predictable that physicians are less likely to pursue treatment for burnout and related mental health issues. A recent study found that 50 percent of the female physicians who believed they had a mental illness failed to seek treatment (Gold et al., 2016). Among the reasons for failing to seek treatment were (1) a belief in the ability to self-manage; (2) time constraints; and (3) feelings of embarrassment or shame associated with a diagnosis. Other studies found that physicians refrain from seeking help because it may affect their ability to practice medicine because the information may be reportable to the state licensing boards (Gold et al., 2016; Shanafelt et al., 2011).

Addressing Physician Wellness from an Osteopathic Approach

At the center of wellness is resilience, which reflects an individual’s ability to positively respond to stress—which, in turn, promotes wellness. The ability to thrive in a particular environment is different for one person versus another. Different life events and experiences influence a person’s ability to flourish in a stressful environment, such as the medical field, which oftentimes includes adversity. It is not a stretch to include resilience as a component of the osteopathic approach to physician wellness. The osteopathic approach does not look at patients, in this case physicians, in a vacuum, but rather, it looks at all facets of the patient’s life, which includes physical, social, emotional, and mental elements.

Resilience

While resilience requires the osteopathic profession to consider all of the aspects of a person’s life, it also requires an approach that considers them across the life cycle of a physician’s career (i.e., pre-medical through retirement), and the stakeholders involved at the various stages (i.e., the American Osteopathic Association [AOA], family, medical schools, training programs, specialty colleges, state affiliates, and employers) when addressing physician wellness. Test scores and entrance exams cannot predict who is truly prepared for medical school or the stress of a medical career. An osteopathic approach examines the full body of work of a potential candidate—there is a balance between test scores and life experiences. Thus, in addressing burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation among physicians, an osteopathic approach is holistic. It should address stressful issues during all stages of career development because failure to do so can have lasting ramifications for a physician mentally, emotionally, socially, and physically. Too often there is a tendency for key stakeholders to focus on the end goal, such as completing medical school or completing a training program, and ignore or minimize the fact that a person is having difficulty coping or positively resolving issues. The AOA and its leaders accept the responsibility they have to the osteopathic profession to change this culture of expediency, destigmatize mental health concerns, and improve fitness to practice by encouraging wellness. The AOA is committed to engaging all levels of the profession and promoting a shared vision to encourage physician wellness.

Additionally, the AOA recognizes that burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation extend beyond the student/physician, but also affect family, friends, and ultimately, patients. Family and friends often suffer in silence when a student’s/physician’s wellness is challenged or he or she suffers from mental health issues. Consequently, an osteopathic approach must recognize key stakeholders and their role in the treatment process.

A Strategic Path Forward

The medical field has typically managed physician wellness in silos. For example, medical schools generally handle issues within their four walls and then send students off to residency training; training programs, in turn, send the new physician off to practice, at which time the respective specialty society and state association may be asked to help find assistance to address any remaining issues. With the latest developments and statistics regarding physician burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation, the osteopathic profession can ill afford to stay this course. A concerted effort to implement a continuity of care across a physician’s life cycle is the answer. This continuity of care must be flexible as wellness is not based on a continuum, but rather, fluctuates for various reasons (e.g., a physician may experience a loss of a family member and the immediate result may be depression; burnout, as defined above, may never be a factor).

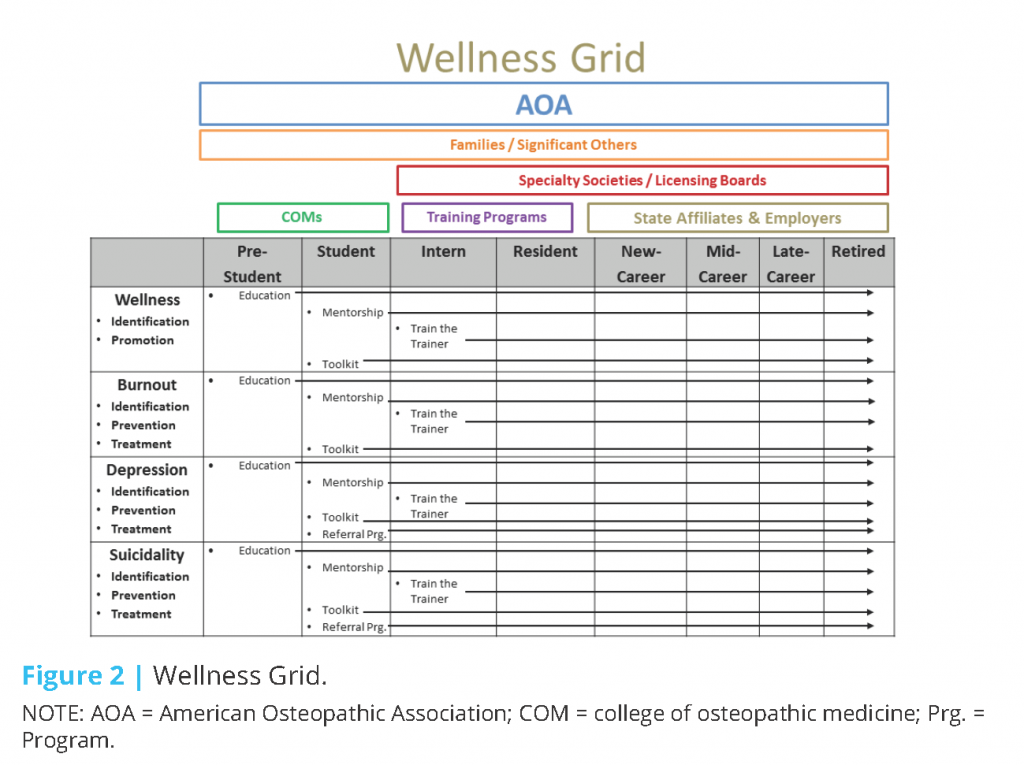

As reflected in Figure 2 (created by Robert G. G. Piccinini, DO, DFACN, chair of the AOA’s Physician Wellness Taskforce), each phase of career development brings forth its own set of unique experiences and challenges as well as opportunities for physician wellness. To ensure physician wellness, it is imperative that a physician successfully negotiate each stage of development. There will be common themes and solutions that feature the various stakeholders. These stakeholders may serve as resources and allies that facilitate personal development, effective mentorship, and safe zones void of negative judgment from colleagues and superiors. Additionally, the continuous sharing of information on resources, best practices, and changing trends across the physician life cycle and among the various stakeholders is required.

School Programs and Mental Health Faculty (Pre-Medical Student to Medical Student Level)

Colleges and schools of osteopathic medicine (COMs) must adopt a culture wherein students having difficulty coping with various life stressors may have an open discourse with faculty without fear of judgment, stigmatization, or other retribution. This culture can be achieved by medical schools implementing active and visible behavioral health programs and encouraging faculty to serve as mentors and confidants. In addition, medical schools should provide outside resources (e.g., physicians, counselors, therapists, and programs) to enable students to obtain the needed assistance and maintain privacy during treatment.

Privacy and confidentiality are an absolute requirement of all implemented programs. Students must know and believe their privacy is protected and that faculty and the administration will treat each situation with confidentiality. Such confidentiality shall not be broken unless there is potential harm to the student or others.

Another opportunity to change the culture of medical schools in the handling of mental health issues is to incorporate wellness training into the curriculum. This change would require the AOA to make a recommendation to the Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation (COCA), which is the accrediting body for COMs. It establishes, maintains, and applies accreditation standards and procedures to ensure that COMs deliver and maintain quality academic programs that reflect the evolving practice of osteopathic medicine. The AOA would need to specifically recommend that COCA develop a standard requiring COMs to integrate a wellness component into their curriculum.

Mentorship/Modeling in Training Programs and Beyond (Medical Student to Late Career Levels)

Mentorship and positive modeling are necessities for physician wellness. They go across all levels of training that occur not only in medical school and residency, but also in early as well as late career stages. There are many formats for mentorship and modeling programs, such as one-on-one mentoring opportunities, webinars, and other live programs targeting 4th-year students and providing insight on what students should expect during residency (e.g., how to prepare for the demands and elevated stress levels).

Other options are train-the-trainer programs. The assumption of being a qualified mentor as something that is inherent in each physician is as an archaic concept as the traditional “See one, do one, teach one.” The qualities of effective mentorship must be taught. Training the trainer (modeling/mentoring) programs should be considered a faculty development activity that includes periodic refresher courses. Mentors should not only convey the ideas of wellness, but also model the behaviors and attitudes that support physician well-being (e.g., mental health, job satisfaction). Medical schools, training institutions, and state and specialty associations must collaborate to offer these programs and ensure their sustainability.

State associations may serve a special role in the mentorship process. They have the ability to connect practicing physicians across different specialties. This is particularly attractive to those physicians reluctant to seek the advice of a colleague in their own specialty for fear it could negatively impact future career options.

Licensing boards may be another stakeholder that can assist in mentorship through educational programs or other activities.

Opportunities to Reach Practicing and Retired Physicians (Early Career to Retirement Levels)

The AOA will work with the state and specialty affiliates to develop continuing medical education (CME) and non-CME initiatives regarding physician wellness. These programs would promote self-wellness (e.g., nutrition, exercise, mindfulness, and life-work balance) and could be offered at the AOA’s annual conference as well as other venues of states and affiliates where physicians regularly meet. Online programs would also serve as an option.

In addition to structured educational programs, a toolkit could be beneficial to the physician community. This toolkit would provide information on risk factors and protective measures; identify resources; and include “real life” stories of physicians who have successfully navigated their mental health issues. Physicians could access this toolkit at their leisure and for various purposes, such as for their own mental health benefit or to assist a colleague or a mentee.

Another key opportunity to promote wellness for practicing physicians involves licensing boards. Licensing boards, by their nature, serve as regulators of the profession. They function to provide safe patient care of state residents and their visitors. They investigate complaints, determine and execute disciplinary actions, and refer physicians to physician health programs (PHPs) to determine fitness to practice for patient safety. Some physicians fear seeking help for mental health issues because they believe it may be seen as a “black mark” on their record and hinder their career aspirations (Gold et al., 2016). The stigma of mental health is so pervasive that many physicians may feel that mental health issues are a sign that they are unable to cope with the rigor of the medical profession, and therefore, their ability to care for patients is inferior to other physicians. Thus, the traditional role of licensing boards can frustrate efforts to promote physician wellness.

The AOA and the state or specialty associations may be best positioned to help alleviate the added stress physicians may experience as they interact with their respective licensing boards. The AOA should enter into a more sophisticated discussion with the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) regarding the benefits and potential challenges of physicians reporting mental health concerns. Encouraging licensing boards to promote physician wellness can reframe this traditional reputation.

Conclusion

The medical profession is constantly evolving with the world around it. The demands and stresses new generations of physicians may face can have a profound effect on their personal lives and careers as well as the patients for whom they care. It is imperative that medical schools, training programs, employers, families/significant others, medical organizations, and society as a whole recognize that the public perception and reality of physicians can be drastically different. Current physicians are facing high education debt, excessive workloads, increased volume and complexity of medical knowledge, new and ever-changing reporting requirements, an aging population that is increasing patient volume and care complexity, patients using Internet sources and social media to educate and self-diagnose, and an over-litigious society. Physicians are facing these pressures along with the demands of raising families, caring for elderly parents, managing finances, and other stresses of many citizens in today’s society. In light of these overwhelming challenges, burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation are real. Physician wellness must be a priority, and is imperative for a healthy society.

The osteopathic approach is to examine the whole picture and not individual snippets of a physician’s life. The experiences and skills honed across physicians’ life cycles will determine their ability to meet the challenges of these times and obtain optimal wellness (mind, body, and soul). The osteopathic approach requires key stakeholders to play a role in facilitating wellness. As set forth above, it is a multi-prong approach that touches on education, mentorship and positive modeling, resources, and candid discussions and requires flexibility. As each generation progresses through their careers, the difficulties they face and the skill set they bring to the table will need to be scrutinized and modified. Ultimately, physician wellness requires collaboration and a long-term commitment from all.

Notes

- Osteopathic medicine is a distinct branch of medical practice in the United States. It is based on a philosophy of medicine that all systems of the human body are interrelated, each working with the other to heal in times of illness. Doctors of Osteopathic Medicine, or DOs, are fully licensed physicians who practice in every medical specialty. DOs practice a whole-person approach to medicine, focused on looking beyond symptoms to understand how lifestyle and environmental factors affect well-being.

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. 2017. Physician and medical student depression and suicide prevention. Available at: https://afsp.org/our-work/education/physician-medical-student-depression-suicide-prevention (accessed January 31, 2017).

- Andrew, L. B. 2015. Physician suicide. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/806779 (accessed January 25, 2017).

- AOA (American Osteopathic Association). 2017. Tenets of osteopathic medicine. Available at: http://www.osteopathic.org/inside-aoa/about/leadership/Pages/tenets-of-osteopathic-medicine.aspx (accessed February 1, 2017).

- Downs, N., W. Feng, B. Kirby, T. McGuire, C. Moutier, W. Norcross, M. Norman, I. Young, and S. Zisook. 2014. Listening to depression and suicide risk in medical students: The Healer Education Assessment and Referral (HEAR) program. Academic Psychiatry 38(5):547–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0115-x

- Gold, K. J., A. Sen, and T. L. Schwenk. 2013. Details on suicide among US physicians: Data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. General Hospital Psychiatry 35(1):45–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.08.005

- Gold, K. J., L. B. Andrew, E. B. Goldman, and T. L. Schwenk. 2016. “I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record”: A survey of female physicians on mental health diagnosis, treatment, and reporting. General Hospital Psychiatry 43:51–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.09.004

- Lapinski, J., M. Yost, P. Sexton, and R. J. LaBaere, 2nd. 2016. Factors modifying burnout in osteopathic medical students. Academic Psychiatry 40(1):55–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-015-0375-0

- Mata, D. A., M. A. Ramos, N. Bansal, R. Khan, C. Guille, E. Di Angelantonio, and S. Sen. 2015. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: A systematic review and metaanalysis. JAMA 314(22):2373–2383. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15845

- Petersen, M. R., and C. A. Burnett. 2008. The suicide mortality of working physicians and dentists. Occupational Medicine 58(1):25–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqm117

- Privitera, M. R., A. H. Rosenstein, F. Plessow, and T. M. LoCastro. 2015. Physician burnout and occupational stress: An inconvenient truth with unintended consequences. Journal of Hospital Administration 4(1):27–35. Available at: http://www.sciedu.ca/journal/index.php/jha/article/view/5616 (accessed August 14, 2020).

- Shanafelt, T. D., C. M. Balch, L. Dyrbye, G. Bechamps, T. Russell, D. Satele, T. Rummans, K. Swartz, P. J. Novotny, J. Sloan, and M. R. Oreskovich. 2011. Special report: Suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Archives of Surgery 146(1):54–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2010.292

- Shanafelt, T. D., S. Boone, L. Tan, L. N. Dyrbye, W. Sotile, D. Satele, C. P. West, J. Sloan, and M. R. Oreskovich. 2012. Burnout and satisfaction with worklife balance among us physicians relative to the general US population. Archives of Internal Medicine 172(18):1377–1385. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

- Shanafelt, T. D., O. Hasan, L. N. Dyrbye, C. Sinsky, D. Satele, J. Sloan, and C. P. West. 2015. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 90(12):1600–1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

- Still, A. T. 1902. The philosophy and mechanical principles of osteopathy. Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co.

- West, C. P., L. N. Dyrbye, P. J. Erwin, and T. D. Shanafelt. 2016. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 388(10057):2272–2281. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X

- WHO (World Health Organization). 1992. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958 (accessed August 14, 2020).