A Multifaceted Systems Approach to Addressing Stress Within Health Professions Education and Beyond

TW: suicide

There are unique stressors faced by health professionals that begin during the educational process and continue throughout training and into practice. While stress is expected owing to the intense nature of the work in health are, the systems in which faculty and health professionals work often intensifies this already stressful environment and can lead to negative mental and physical effects. Stress takes a major toll on individuals and has been reported to increase absenteeism, errors, burnout, and substance use, and it can even lead to individuals quitting the health professions altogether (Bond et al., 2015; Brondani et al., 2014; Cooper, 2015; Hayashi et al., 2009; IsHak et al., 2009; Wilkins, 2007).

Individual and institutional costs in the form of strained personal and professional relationships, lower quality of care, and financial expenses associated with diminished physical health and mental well-being of those caring for the population also occur. The disruption for coworkers who rely on burned-out, stressed, or absent colleagues for their expertise significantly impedes team functioning and further degrades the overall quality of the care. While it is indisputable that the nature of the work in health care causes stress, organizations also bear responsibility for accepting and even creating an institutional culture where stress can be worsened by outdated or negative policies and behavioral patterns. Moral distress can be experienced when there is difficulty obtaining appropriate interventions or care to support patients and families (Gallagher, 2011). Further, institutional policies that inhibit inclusivity may create hostility by limiting the diversity of the student body, faculty, and the health profession, themselves; an organizational culture that emphasizes hierarchy over teams and collaboration often creates obstacles to communication, trust, and innovation; and an environment that seems to value measuring the length of clinical appointments and reimbursement over patient quality and safety creates risks and frustrations for everyone. Acknowledgment of the association between stress and working in health and health care has been codified by recent writings expanding the Triple Aim [4] to include a goal to improve

the work life of health professionals (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014).

A Multifaceted Systems Approach to Addressing Stress

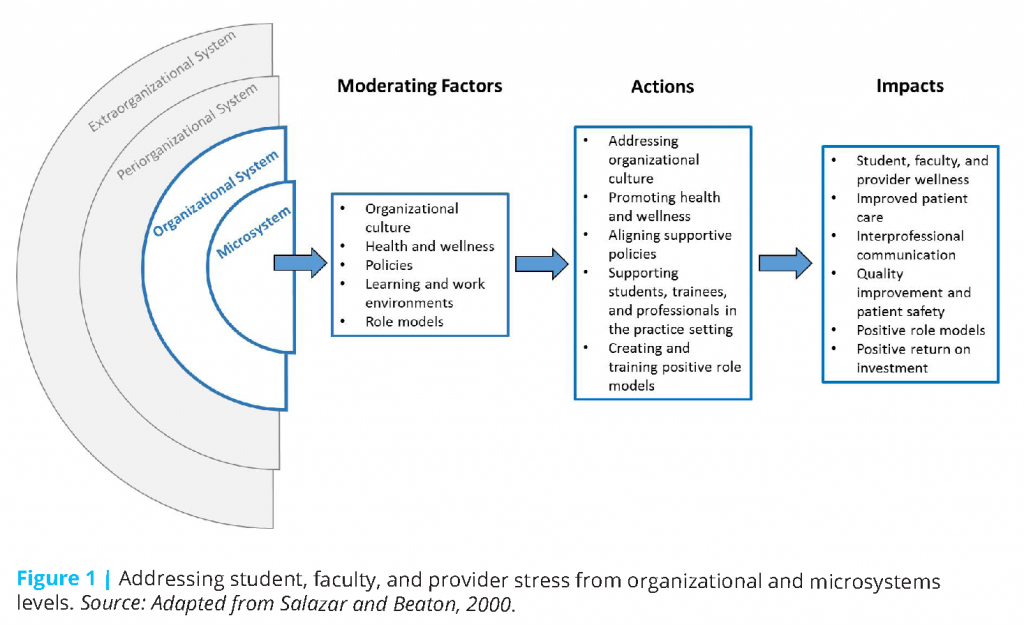

The authors of this paper argue for a bold new strategy for tackling stress in the health professions. This strategy involves taking a multifaceted systems approach that includes everyone across the health professions, beginning in the learning environment, working together toward a common goal of promoting wellness. A systems-based approach acknowledges that stress, anxiety, and depression leading to burnout, suicide, or other unhealthy behaviors do not stem from a single source but rather are the culmination of multiple forces working against health. In their article, Salazar and Beaton (2000) take an ecological approach to occupational stress that looks beyond the individual worker or worker groups to better understand the context in which work-related stress occurs. Salazar and Beaton identified four levels of occupational stressors: (1) the microsystem or the immediate environment of the workers; (2) the organizational system that encompasses all aspects of an organization (e.g., physical structure, cultural context, policies, the work); (3) the periorganizational system including societal influences on the worker or the organization such as the economic situation of the surrounding community; and (4) the extraorganizational system that encompasses cultures, traditions, customs, and government policies that affect the organization.

Using Salazar and Beaton’s ecological model as a guide, the authors believe an innovative way to minimize stress and mediate its negative effects is for representatives from all the health professions and educational and organizational leadership to come together to discuss the stressful environment with specific attention to profession-specific and shared stressors. Engaging this group in discussion using the different levels of occupational stressors will steer the conversation to specific action that would benefit all involved. It is through dialogue and open conversation that different health professionals can better understand the intersections of each profession’s stressors. This would lay the foundation for advancing formal and informal multifaceted systems approaches to problems common to the health professions.

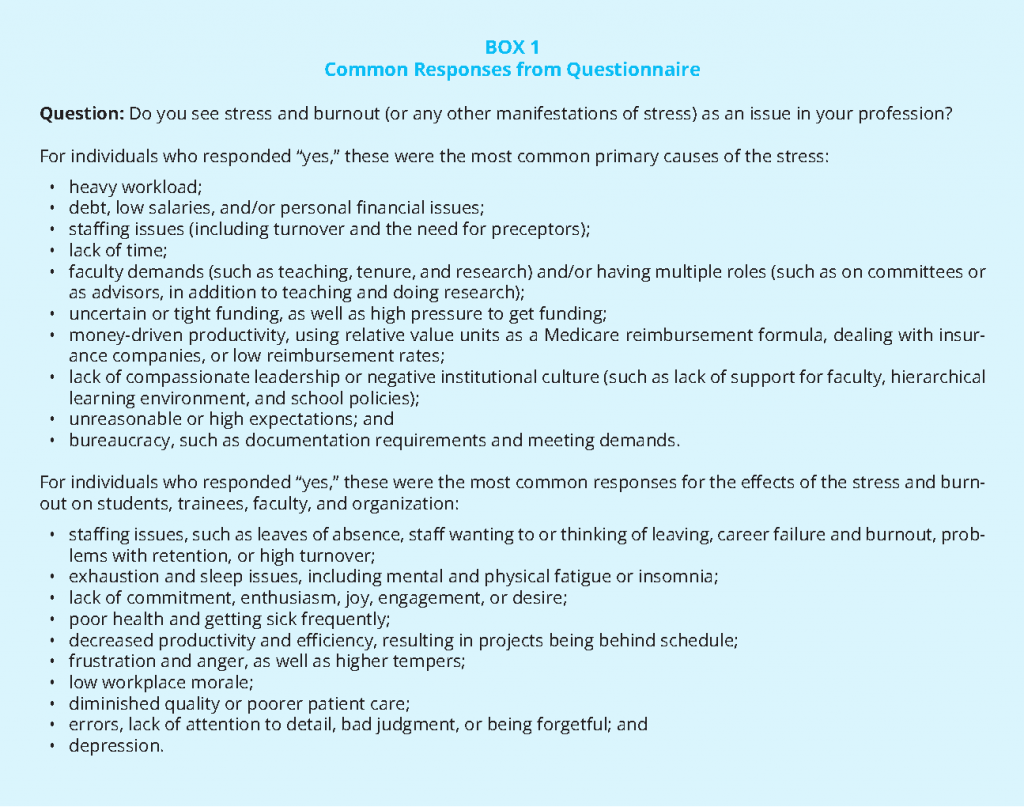

Drawing ideas from a variety of health professions expands thinking for how professions might work together to reduce stressors in the education and practice environments that are or appear unique to one profession. As an example of how a systems approach might begin, the authors of this paper developed a multi-professions questionnaire to gain perspectives on the stressors affecting various professions (see Box 1). The aim was to establish the extent to which various health professions perceive stress as a problem within their profession, and also to assess whether interprofessional interventions are currently used by any professions to try to mitigate the negative impacts of the stress. The questionnaire was distributed to members of the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education and the forum’s e-mail list, and recipients were encouraged to share the questionnaire with their colleagues and wider networks.

The results of the questionnaire included 252 respondents representing 25 different professions working in a variety of settings such as educational, clinical, nonprofit, professional association, government, and funding. More than 90 percent of respondents replied that stress and manifestation of stress are issues in their profession. When asked if their department or organization promoted or provided interventions to combat stress, 40 percent replied “yes.” Roughly one-fourth of respondents replied that they know of formal or informal cross-professions interventions to prevent or reduce stress in their profession. Examples of the specific cross-profession interventions identified by respondents include interprofessional lectures, seminars, or trainings on mindfulness, meditation, stress reduction, and MBSR (mindfulness-based stress reduction); a wellness center or program at the institution; exercise, yoga, wellness, and healthy eating classes; and peer mentoring or discussion groups.

Based on the responses to this questionnaire, it appears that stress is a major factor in all the health professions, and in fact, that there is a track record of it being addressed in some health professions educational programs. As such, this creates an opportunity for the health professions to come together to identify the system-level stressors that if addressed could mitigate undue pressures on all those working within the same environment.

Taking Action

To develop a foundation for dialogue among the professions, representatives from different health professions volunteered to write perspectives that will summarize the types of stresses affecting their profession. As they become available, these perspectives will be published on the websites of the National Academy of Medicine and the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education. The hope is to gather varied input from health professionals, faculty, students, trainees, and administrators who experience unique stressors that could add insight into a multifaceted systems approach to mitigating stress. These perspectives can be later analyzed for overlap among health professions.

The authors of this paper adapted the Salazar and Beaton ecological model to create a model for addressing student, faculty, and provider stress from organizational and microsystem levels. While all four levels of occupational stressors are important to address, the authors focused on identifying actions within the organization and microsystem levels. The adapted model (see Figure 1) shows the moderating factors, which are factors that “can partially buffer, intercept, or negate the effects of the identified stressor…[or] can exacerbate these stressors” (Salazar and Beaton, 2000, p. 475). Based on a review of the existing literature, the following activities present opportunities for future discussion and action (see the bulleted list under “Actions” in Figure 1):

- Addressing organizational culture: Health professional students and staff are frequently subjected to excessive workloads, excessive work hours, and limited or no access to administrative support for relief. While standards to address the problem of organizational culture have been articulated (ACGME, 2014; The Joint Commission, 2008), more attention needs to be placed on how organizations are assessed relative to these standards. Organizations should be recognized for promoting cultures that are supportive of wellness (APA, 2016).

- Promoting health and wellness: With support from education and practice leaders, faculty, preceptors, and other health professionals can deliberately integrate wellness and resiliency activities into all aspects of education and training. Information on wellness as well as resiliency and self-care skills can be embedded into the curriculum to help ameliorate stress and anxiety (Slavin et al., 2014). To incentivize leadership to integrate such practices into university and practice settings, health and wellness of students, faculty, and practitioners can be incorporated into accreditation requirements.

- Aligning supportive policies: Individual wellness and well-being, as well as the development of enduring resiliency skills, must be deliberate and overtly stated goals of training and integrated into organizational cultures, educational designs, and practice settings (Butler et al., 2010; Ohrling and Hallberg, 2001; Slavin, 2014; Smullens, 2015).

- Supporting students, trainees, and professionals in the practice setting: When structures are in place to support students and health workers, healthy environments can be created; within these environments, health professionals and students are encouraged to identify and obtain moral courage to advocate for the right solutions for care and to be leaders in changing negative cultures (Barry et al., 2016; University of Kentucky, 2016).

- Creating and training positive role models: Workplace learning represents a major component of health care students’ learning, as is reflected by the concept of the “hidden curriculum” (Gaiser, 2009) [5]. To help ensure that student–preceptor relationships are healthy and supportive (rather than stressful and punitive), organizations can provide appropriate and adequate preparation and support for preceptors and students (McGregor, 1999; Spector, 2015; Yonge et al., 2002).

The authors believe that by taking these actions, many improvements can be made (see bulleted list under “Impacts” in Figure 1). Educating the health workforce to better understand one’s emotional state and to develop emotional intelligence is a tool for building a more collaborative, team-based patient and person-centered workforce, as well as being a tool for improving care for patients and employees facing challenging situations (Bloom and Farragher, 2010; Conners-Burrow et al., 2013; Kelly et al., 2014; McCallin and Bamford, 2007). A case must be made that a financial return on investment exists from a healthy work environment and a healthy workforce (Arena et al., 2013; Goetzel et al., 2002, 2012). And perhaps most importantly, in order to bring attention to the negative effects stress can have in health professional education and practice, leaders in the academic and service

settings need to acknowledge the problem exists in their environment and emphasize the importance of health and well-being in both students and practicing health professionals.

Next Steps

Students, trainees, faculty, and health professionals all affirm that stress in the health professions has a direct human toll on productivity, efficiency, quality, and the human capital of the workforce. A strategic move is necessary to shift the paradigm and create a new normal—one that is life-affirming, health-oriented, and drives durable changes for the next generation. In following papers, authors from different professions will look at systems-level stressors from each of their individual perspectives. They will explore how their profession responds to such stress within education and practice, and they will offer potential interprofessional interventions that could improve the settings for everyone and create an environment in which all professionals can work together toward health and wellbeing for all.

The cost of stress in the health processions is enormous. It affects not only health care providers but the people and communities they serve as well. While stress-reduction techniques may be helpful for individuals, a systems approach is required to effectively address a problem generated by the system.

Download the graphic below and share it on your social networks!

Notes

- Darla Spence Coffey, Kathrin Eliot, Elizabeth Goldblatt, Catherine Grus, Sandeep Kishore, Beth Mancini, Richard Valachovic, and Patricia Hinton Walker are members of the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Patricia Cuff is director of the forum. For more information about the forum, visit nationalacademies.org/ihpeglobalforum.

- The authors are grateful for the insights and assistance of Patricia Cuff, director of the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

- The authors were assisted by Megan Perez, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

- The Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim is a framework for health system performance involving (1) better patient care, (2) improved population health, and (3) reduced health care costs (IHI, 2017).

- The hidden curriculum “consists of the unspoken or implicit academic, social, and cultural messages that are communicated to students” while in learning events (The Glossary of Education Reform, 2015).

References

- ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education). 2014. CLER pathway to excellence: Expectations for an optimal clinical learning environment to achieve safe and high quality patient care. Chicago, IL:

ACGME. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/CLER/CLER_Brochure.pdf (accessed August 10, 2020). - APA (American Psychological Association). 2016. American Psychological Association Center for Organizational Excellence. Available at: http://www.apaexcellence.org (accessed January 23, 2017).

- Arena, R., M. Guazzi, P. D. Briggs, L. P. Cahalin, J. Myers, L. A. Kaminsky, D. E. Forman, G. Cipriano, Jr., A. Borghi-Silva, A. S. Babu, and C. J. Lavie. 2013. Promoting health and wellness in the workplace: A unique opportunity to establish primary and extended secondary cardiovascular risk reduction programs. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 88(6):605-617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.03.002

- Barry, D., T. Houghton, and T. Warburton. 2016. Supporting students in practice: Leadership. Nursing Standard 31(4):46-53. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2016.e9669

- Bloom, S. L., and B. J. Farragher. 2011. Destroying sanctuary: The crisis in human service delivery systems. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bodenheimer, T., and C. Sinsky. 2014. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine 12(6):573-576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

- Bond, K. S., A. F. Jorm, B. A. Kitchener, and N. J. Reavley. 2015. Mental health first aid training for Australian medical and nursing students: An evaluation study. BMC Psychology 3(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-015-0069-0

- Brondani, M. A., D. Ramanula, and K. Pattanaporn. 2014. Tackling stress management, addiction, and suicide prevention in a predoctoral dental curriculum. Journal of Dental Education 78(9):1286-1293. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25179925/ (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Butler, L. D., E. S. Rinfrette, D. Coppola, and S. Reiser. 2010. University at Buffalo School of Social Work self care starter kit. Available at: http://www.socialwork.buffalo.edu/students/self-care/index.asp (accessed November

30, 2016). - Conners-Burrow, N. A., T. L. Kramer, B. A. Sigel, K. Helpenstill, C. Sievers, and L. McKelvey. 2013. Trauma-informed care training in a child welfare system: Moving it to the front line. Children and Youth Services

Review 35(11):1830-1835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.08.013 - Cooper, J. 2015. Stand up for social work: Discuss the results of our burnout research with your manager. Community care research shows majority of social workers are emotionally exhausted with poor supervision

making it worse. Avaiable at: http://www.communitycare.co.uk/2015/07/27/stand-social-work-discuss-results-burnout-research-manager (accessed December 8, 2016). - Gaiser, R. R. 2009. The teaching of professionalism during residency: Why it is failing and a suggestion to improve its success. Anesthesia & Analgesia 108(3):948-954. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e3181935ac1

- Gallagher, A. 2011. Moral distress and moral courage in everyday nursing practice. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 16(2):8. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No02PPT03

- Goetzel, R. Z., R. J. Ozminkowski, L. I. Sederer, and T. L. Mark. 2002. The business case for quality mental health services: Why employers should care about the mental health and well-being of their employees. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 44(4):320-330. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-200204000-00012

- Goetzel, R. Z., X. Pei, M. J. Tabrizi, R. M. Henke, N. Kowlessar, C. F. Nelson, and R. D. Metz. 2012. Ten modifiable health risk factors are linked to more than one-fifth of employer-employee health care spending. Health Affairs (Millwood) 31(11):2474-2484. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0819

- Hayashi, A. S., E. Selia, and K. McDonnell. 2009. Stress and provider retention in underserved communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 20(3):597-604. Available at: http://www.clinicians.org/images/upload/Stress_and_Provider_Retention.pdf (accessed August 10, 2020).

- IHI (Institute for Healthcare Improvement). 2017. The IHI Triple Aim. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAIM (accessed January 24, 2017).

- IsHak, W. W., S. Lederer, C. Mandili, R. Nikravesh, L. Seligman, M. Vasa, D. Ogunyemi, and C. A. Bernstein. 2009. Burnout during residency training: A literature review. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 1(2):236-242. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-09-00054.1

- Kelly, U., M. A. Boyd, S. M. Valente, and E. Czekanski. 2014. Trauma-informed care: Keeping mental health settings safe for veterans. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 35(6):413-419. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.881941

- McCallin, A., and A. Bamford. 2007. Interdisciplinary teamwork: Is the influence of emotional intelligence fully appreciated? Journal of Nursing Management 15(4):386-391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00711.x

- McGregor, R. J. 1999. A precepted experience for senior nursing students. Nurse Educator 24(3):13-16. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006223-199905000-00009

- Ohrling, K., and I. R. Hallberg. 2001. The meaning of preceptorship: Nurses’ lived experience of being a preceptor. Journal of Advanced Nursing 33(4):530-540. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01681.x

- Salazar, M. K., and R. Beaton. 2000. Ecological model of occupational stress. Application to urban firefighters. Official Journal of the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses 48(10):470-479. Available at: http://europepmc.org/article/med/11760257 (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Slavin, S. J., D. L. Schindler, and J. T. Chibnall. 2014. Medical student mental health 3.0: Improving student wellness through curricular changes. Academic Medicine 89(4):573-577. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000166

- Smullens, S. 2015. Burnout and self-care in social work: A guidebook for students and those in mental health and related professions. Washington, DC: NASW Press. Available at: https://www.naswpress.org/publications/profession/burnout-self-care.html (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Spector, N. 2015. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing’s transition to practice study: Implications for educators. Journal of Nursing Education 54(3):119-120. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20150217-13

- The Joint Commission. 2008. Sentinel event alert: Issue 40, July 9, 2008: Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Oak Brook, IL: The Joint Commission. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/deprecated-unorganized/imported-assets/tjc/system-folders/topics-library/sea_40pdf.pdf?db=web&hash=D12B14016B1EA82EC1F1395AB6C3B929 (accessed August 10, 2020).

- The Glossary of Education Reform. 2015. Hidden curriculum. Available at: http://edglossary.org/hidden-curriculum (accessed January 24, 2017).

- University of Kentucky. 2016. The Moral Distress Education Project. Available at: http://moraldistressproject.med.uky.edu/moral-distress-home (accessed December 7, 2016).

- Wilkins, K. 2007. Work stress among health care providers. Health Reports 18(4):33-36. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18074995/ (accessed August 10, 2020).

- Yonge, O., H. Krahn, L. Trojan, D. Reid, and M. Haase. 2002. Being a preceptor is stressful! Journal for Nurses in Staff Development 18(1):22-27. https://doi.org/10.1097/00124645-200201000-00005