Vital Directions for Health and Health Care: Priorities from a National Academy of Medicine Initiative

The United States is poised at a critical juncture in health and health care. Powerful new insights are emerging on the potential of disease and disability, but the translation of that knowledge to action is hampered by debate focused on elements of the Affordable Care Act that, while very important, will have relatively limited impact on the overall health of the population without attention to broader challenges and opportunities. The National Academy of Medicine has identified priorities central to helping the nation achieve better health at lower cost.

Context: Fundamental Challenges

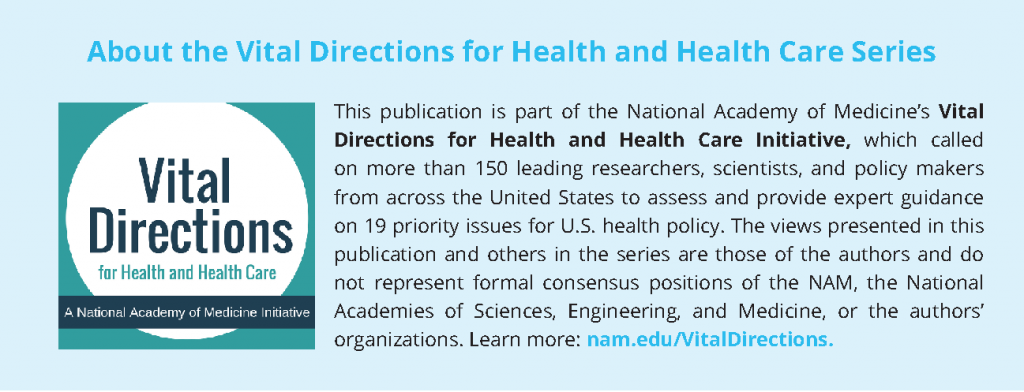

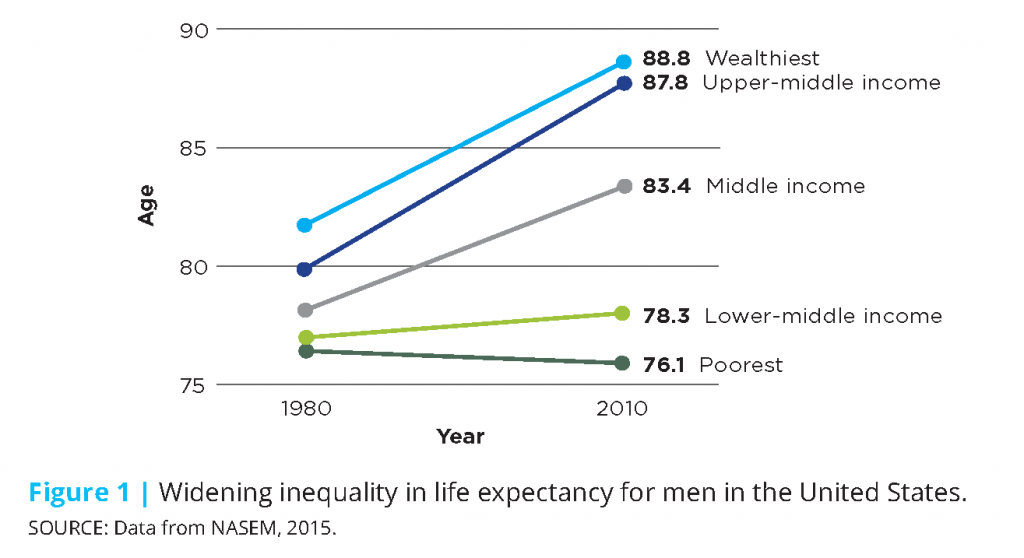

Health care today is marked by structural inefficiencies, unprecedented costs, and fragmented care delivery, all of which place increasing pressure and burden on individuals and families, providers, businesses, and entire communities. The consequent health shortfalls are experienced across the whole population, but disproportionately impact our most vulnerable citizens due to their complex health and social circumstances. This is evidenced by the growing income-related gap in life expectancy for both men and women (see Figures 1 and 2). Today, higher-income men can expect to live longer than they did 20 years ago, while life expectancy for low-income males has not changed. Higher-income women are also anticipated to live longer, but life expectancy for low-income women is projected to decline.

Beyond systemic and structural issues, this country is faced with serious public health challenges and threats: emerging infectious diseases; an evolving opioid epidemic; alarming rates of tobacco use, obesity, and related chronic diseases; and a rapidly aging population that requires great support from our health care delivery and financing systems. Following are summarized fundamental challenges with which our health and health care system must be better prepared to contend.

Persistent Inequities in Health

In spite of the United States’ great investment in health care services and the state-of-the-art health care technology available, inequities in health care access and status persist across the population and are more widespread than in peer nations (Lasser et al., 2006; Avendano, 2009; van Hedel et al., 2014; Siddiqi et al., 2015). Over the past 15 years, individuals in the upper income brackets have seen gains in life expectancy, while those in the lowest income brackets have seen modest to no gains (Chetty et al., 2016). And while health inequities are seen most acutely across socioeconomic and racial/ethnic lines, they also emerge when comparing other characteristics such as age, life stage, gender, geography, and sexual orientation (Braveman et al., 2010; Artiga, 2016). However, health status is not predetermined; rather, is the result of the interplay for individuals and populations of genetics, social circumstances, physical environments, behavioral patterns, and health care access (McGinnis et al., 2002). Similarly, inequities in health are not inevitable (Adler et al., 2016; McGinnis et al. 2016); efforts to lessen social disadvantage, prevent destructive health behaviors, and improve built environments could have important health benefits.

Rapidly Aging Population

By 2060, the number of older persons (ages 65 years or older) is expected to rise to 98 million, more than double the 46 million today; in total population terms, the percentage of older adults will rise from 15% to nearly 24 (Mather et al., 2015; ACL, 2016). This trend is explained by the fact that people are living longer and the baby boomers are entering old age. The aging population is placing increasing demand on our health care delivery, financing, and workforce systems, including informal and family caregivers. As more and more people age, rates of physical and cognitive disability, chronic disease, and comorbidities are anticipated to rise, increasing the complexity and cost of delivering or receiving care. In particular, Medicare enrollments and related spending will rise, as will Medicaid and out-of-pocket spending for long-term care services not provided under Medicare (CMS 2016a; ACL, 2016). Ensuring that the elderly can be adequately cared for and supported will require greater understanding of their social, medical, and long-term needs, as well as workforce skills and care delivery models that can provide complex care (Rowe et al., 2016).

New and Emerging Health Threats

U.S. public health and preparedness has been strained by a number of recent high profile challenges, such as lead-contaminated drinking water in several of our cities; antibiotic resistance; mosquito-borne illnesses such as Zika, Dengue, and Chikungunya; diseases of animal origin, including HIV, influenzas, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and Ebola; and devastating natural disasters, such as hurricanes Sandy and Katrina (Morens and Fauci, 2013). The emergence of these threats, and in some cases the related responses, highlights the need for the public health system to better equip communities to better identify and respond to these threats.

Persisting Care Fragmentation and Discontinuity

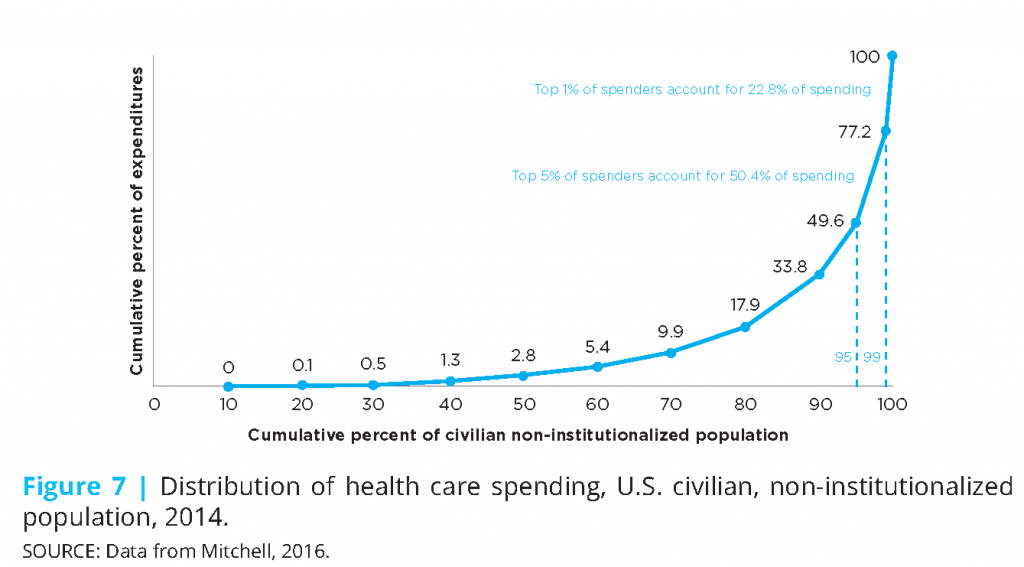

While recent efforts on payment reform have aimed to advance coordinated care models, much of health care delivery still remains fragmented and siloed. This is particularly true for complex, high-cost patients—those with fundamentally complex medical, behavioral, and social needs. Complex care patients include the frail elderly, those who are disabled and under 65 years old, those with advanced illness, and people that have multiple chronic conditions (Blumenthal et al, 2016). High-need, high-cost patients comprise about 5% of the patient population, but drive roughly 50% of health care spending (Cohen and Yu, 2012). Individuals with chronic illness and/or behavioral health conditions often experience uncoordinated care which has been shown to result in lower quality care, poorer health outcomes, and higher health care costs (Druss and Walker, 2011; Frandsen et al., 2015).

Health Expenditure Costs and Waste

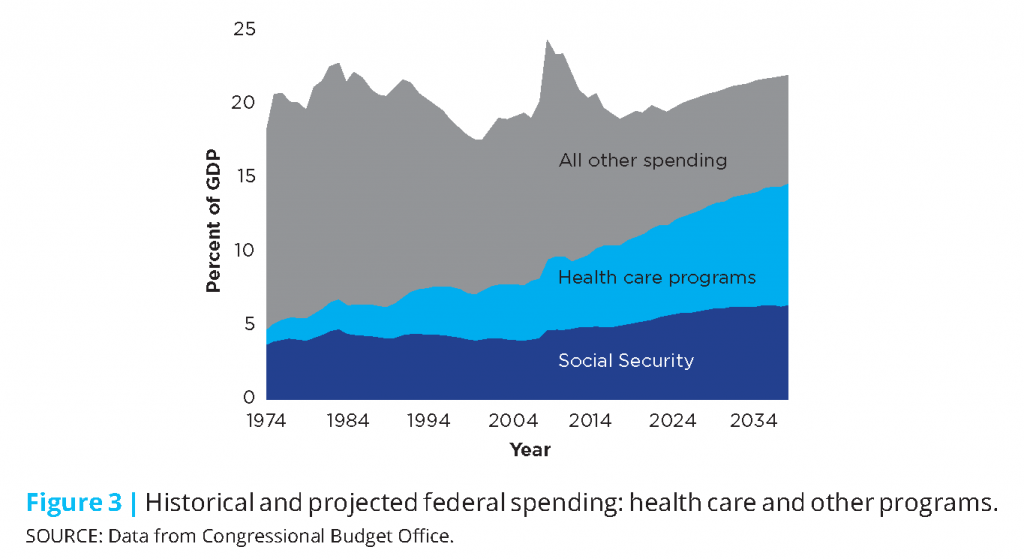

It is widely acknowledged that the U.S. is experiencing unsustainable cost growth in health care: spending is higher, coverage costs are higher, and the costs associated with gaining access to the best treatments and medical technologies are similarly increasing. In 2015, health care spending grew 5.8%, totaling $3.2 trillion or close to 18% of GDP. Of that, it has been estimated that approximately 30% can be attributed wasteful or excess costs, including costs associated with unnecessary services, inefficiently delivered services, excess administrative costs, prices that are too high, missed prevention opportunities, and fraud (IOM 2010; IOM 2013). Resources consumed in this way represent significant opportunity costs both in terms of higher-value care that could be pursued, and in terms of the social, behavioral, and other essential services necessary for effective care and good outcomes. Figure 3 shows how rising federal spending on health care programs, as a percentage of GDP, is outpacing and compressing other parts of the federal budget.

Constrained Innovation Due to Outmoded Approaches

The U.S. has long been a global leader in biomedical innovation, but our edge is increasingly at risk due to outdated regulatory, education and training models. In the drug and medical device review and approval process, uncertainty and unpredictability around approval expectations adds complication, delay, and expense to the research and development process, and can translate to a disincentive to investors (Battelle, 2010). Simultaneously, there are concerns that the movement toward population-based payment models may stifle innovation and patient access by placing excessive burden on manufacturers to demonstrate the value of their products upfront in approval and reimbursement decisions. Further, our biomedical education and scientific training pathways are outdated and fragmented (Kruse, 2013; Zerhouni et al., 2016). Talented young scientists are increasingly discouraged from pursuing careers in biomedical research due to rising educational requirements and tuition costs combined with uncertain career pathways.

Context: Realistic Tools

The good news is that the nation is equipped to tackle these formidable challenges from a position of unprecedented knowledge and substantial capacity. Locally and nationally, new models of care delivery and payment are emerging that seek to reduce waste by rewarding value over volume, are more patient-centric, and are driving better care coordination and integration. The rise of digital health technology has opened the door to enhanced health care and provider access, greater patient engagement, as well as data and tools to support more personalized and tailored health care. Further, increased recognition of the importance of community and population health strategies has helped foster a greater system-wide focus on prevention and overall health promotion opportunities. And, thanks to major advancements and continued innovation in biomedicine and technology, diagnostic capabilities and treatments have expanded greatly, allowing Americans to live longer, more productive lives. Following are several of the crosscutting opportunities for progress identified over the course of the initiative and its work.

A New Paradigm of Health Care Delivery and Financing

Against the backdrop of fee-for-service payment models that can incentivize unnecessary or duplicative care, progress is underway toward a more value-based, person-centric approach. This transformation represents a common effort stemming from the initiative from many quarters—health care leaders, providers, policymakers, and academic experts—responding to rising health care costs, deficiencies in care quality, and inefficient spending. Under fee-for-service, health care services are paid for by individual units, incentivizing providers to order more tests and administer more procedures, sometimes irrespective of need or expected benefit to the patient. In contrast, value-based, alternative payment models (APMs) incentivize providers to maintain or improve the health of their patients, while reducing excess costs by delivering coordinated, cost-effective, and evidence-based care.

Fully Embracing the Centrality of Population and Community Health

With the increasing emphasis on value-based care, and with increasing recognition that factors outside of health care are among the strongest determinants of the health and health care needs of individuals and population segments, efforts are growing to strengthen the activities, tools, and impact related to and community health in U.S. health care today (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003). It is increasingly acknowledged that effective measures to improve health status and health outcomes over groups and over time require tending to the conditions and factors that affect individual and population health over the life course, including social, behavioral, and environmental determinants. While health care in the United States has developed on a track substantially apart from, and generally uncoordinated with, programs directed to the other determinants (Goldman et al., 2016), great gains stand to be achieved if they are more effectively integrated into care delivery and planning.

Increased Focus on Individual and Family Engagement

While calls to more effectively and meaningfully engage patients and their families in care design and decisions are not new, the awareness of the importance to clinical outcomes has increased substantially, as have the tools to facilitate that engagement (Topol, 2015). Today, there is increased focus on expanding the roles of individuals and families in not only designing and executing health care regimens, but in measuring progress, and in developing and testing new and innovative treatments. Across the care continuum, there is greater recognition that patients and families—as the end-users of the services provided—are an integral part of the decision process, whose engagement, understanding, and support is imperative to individual health and well-being, as well as system efficiency, quality, and overall performance.

Biomedical Innovation, Precision Medicine, and New Diagnostic Capabilities

Biomedical science and innovation has accelerated at a tremendous pace, and, with increasing knowledge, available treatments and technologies to combat illness and disease, Americans are able to live longer, healthier lives. Since the 1980s, nearly 300 novel human therapeutics have been approved covering more than 200 indications (Evens and Kaitin, 2015). Breakthroughs in biotechnology have generated new treatments and cures for diseases that were previously untreatable or could only be symptomatically managed, such as cardiovascular disease, HIV, and Hepatitis C. Diagnostics have also become more sophisticated and precise, as diagnostic capabilities have expanded. Today, the field of precision medicine is emerging and has the potential to transform medicine by tailoring diagnostics, therapeutics, and prevention measures to individual patients (Dzau et al., 2016). Precision medicine has great promise to improve care quality by delivering more accurate and targeted treatments, and increase care efficiency by reducing the use of multiple and/or ineffective tests and therapies.

Advances in Digital Technology and Telemedicine

The ability exists to build a continuously learning health system (IOM, 2007; 2013). Health and health care are being fundamentally transformed by the development of digital technology with the potential to deliver information, link care processes, generate new evidence, and monitor health progress (Perlin et al., 2016). Health information technology includes electronic health records (EHRs), personal health records, e-prescribing, and m-health (mobile health) tools, including personal health tools, such as personal wellness devices and smartphone apps, and online peer support communities (ONC, 2013). All of these technologies are changing the way the health system operates, how individuals interact with the health system and one another, and the data available to monitor and improve health and make care decisions. Technological advances in the health arena have also enabled the rise of telemedicine, which allows patients and clinicians to interact with one another remotely.

Promise of “Big Data” to Drive Scientific Progress

Rapid advancement in cost-effective sensing and the expansion of data-collecting devices have enabled massive datasets to be continuously produced, assembled, and stored. The amount of high-dimensional data available is unprecedented and will only continue to grow. If effectively harnessed and curated, big data could enable science to “extend beyond its reach” and allow technology to become more “adaptive, personalized, and robust (NRC, 2013).” In particular, these largescale data stores have the potential to reveal and further our understanding of subtle population patterns, heterogeneities and commonalities that are inaccessible in smaller data (Fan et al., 2014). Using big data, we can learn more about disease causes and outcomes, advance precision medicine by creating more precise drug targets, and better predict and prevent disease occurrence or onset (Khoury and Ioannidis, 2014).

The National Academy of Medicine Initiative

Over a year ago, mindful of the 2017 transition in the Presidency, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM, formerly the Institute of Medicine) launched an initiative to marshal and make available the best possible health and health care expertise and counsel for the incoming Administration, policymakers, and health leaders across the country. In doing so, the NAM is responding to the chartered mandate of the National Academies and its long-standing record of providing trusted and independent counsel. Appropriate to the centrality of the issues, this initiative is named Vital Directions for Health & Health Care. This paper synthesizes the range of compelling opportunities identified over the course of the initiative and presents strategic priorities for the next Administration and the nation’s health leaders to undertake now and in the years ahead.

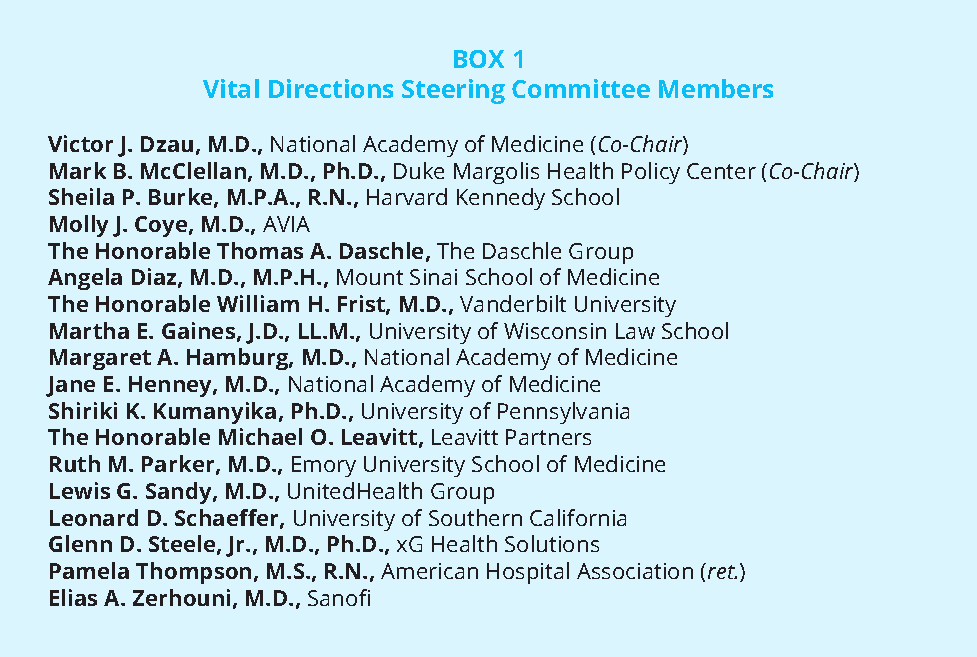

To guide the initiative, the NAM convened a Steering Committee of respected leaders from the health, health care, science, and policy communities (see Box 1). Although the activity is expressly non-partisan, participants include those who have held cabinet-level posts and key legislative responsibilities under both major parties.

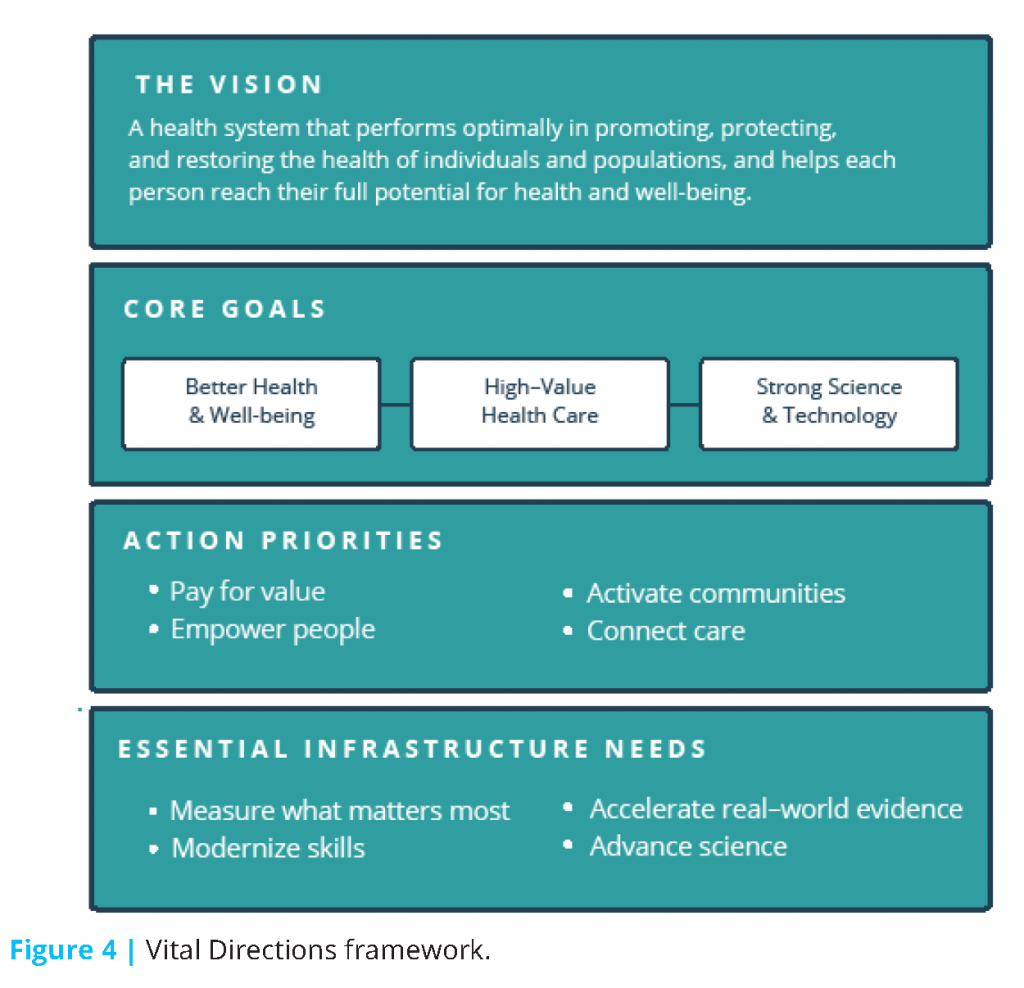

The Vital Directions initiative is rooted in a vision of a health system that performs optimally in promoting, protecting, and restoring the health of individuals and populations, and helps each person reach their full potential for health and well-being (see Figure 4). To achieve this vision requires simultaneously pursuing three core goals for the nation—better health and well-being, high-value health care, and strong science and technology—through advancing strategic action priorities and essential infrastructure needs.

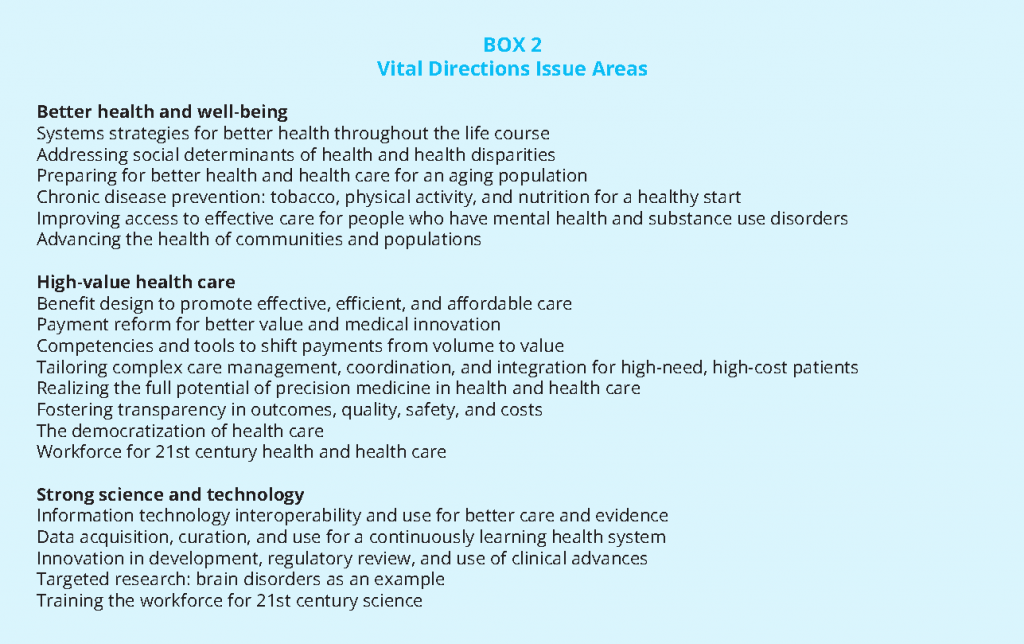

Based on invited suggestions from the public, health and health care communities, and their own collective evaluation, the steering committee identified for assessment the most important issues to realizing the nation’s health prospects, now and in the years ahead, ultimately selecting nineteen issue areas across the three goals (see Box 2). More than 150 of the best-respected health leaders and scholars in the nation were invited to analyze the nineteen issue areas in the form of expert discussion papers. For each issue area, authors were asked to identify the key challenges and strategic opportunities for progress—recommended vital directions—and to offer suggestions on effective ways for policymakers to act on those opportunities.

Each paper underwent a rigorous peer review and revision process before being posted on the NAM website for public review and comment, and then published in final form. In addition, summaries of the papers were published as Viewpoints in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). On September 26, 2016, the NAM hosted a public symposium—”A National Conversation”—to discuss and receive stakeholder feedback on the recommendations proposed in the discussion papers, to explore cross-cutting themes and priorities, and identify outstanding issues and questions. The comments received at the symposium, in response to the web posting, and in response to the JAMA publication informed the final versions of the papers, and were a resource for our identification of the priorities presented below.

Vital Directions for Health and Health Care: The Priorities

Across the total of 68 recommended vital directions identified by the 19 author groups—each important to progress in health, health care, and biomedical science—certain elements are clearly common to each. It is those elements that we present as the nation’s most compelling health priorities. To achieve and sustain health and health care system that is most effective in helping all people reach their full potentials for health and well-being, to better secure our fiscal future, and to provide the global leadership that is expected from the United States, it essential that all levels of leadership act on four action priorities and four essential infrastructure needs for health and health care.

Action Priorities

These priorities address what are, in many ways, the greatest contributors to deficiencies in health system performance but are among the most tangible opportunities to make substantial impact and progress.

- Pay for value—deliver better health and better results for all

- Empower people—democratize action for health

- Activate communities—collaborate to mobilize resources for health progress

- Connect care—implement seamless digital interfaces for best care

Essential Infrastructure Needs

The necessary underpinnings for an accountable, efficient, and modern health system that will strengthen the impact and better ensure the success of the action priorities.

- Measure what matters most—use consistent core metrics to sharpen focus and performance

- Modernize skills—train the workforce for 21st-century health care and biomedical science

- Accelerate real-world evidence—derive evidence from each care experience

- Advance science—forge innovation-ready clinical research processes and partnerships

The Action Priorities

Four cross-cutting action priorities are clearly evident: pay for value, empower people, activate communities, and connect care. Whether from the perspective of the need to reduce the causes and improve the management of heart disease, cancer, or diabetes, to prevent, identify, and treat people with problems of mental health and addiction, or to streamline and improve access to the range of services needed, these four strategic directions are indeed vital. Much greater advantage needs to be taken of what has been learned about the importance of helping people take more personal control of their health and health care, strengthening locally-based efforts and resources, reducing the fragmentation of care processes, and focusing payments on the quality of the results achieved. New insights about their successful engagement underscore the importance of these strategies, but because they represent a substantial departure from current trends, their advancement requires strong commitment and leadership.

Pay for Value – Deliver Better Health and Better Results for All

Design and promote health financing strategies, policies, and payments that support the best results—the best value—for individuals and the populations of which they are a part.

Health expenditures in the United States are far above those in other countries, in part because, when it comes to payments, the notion of “health” has been explicitly linked to the provision and consumption of discrete health care services, and sometimes without consideration of necessity, effectiveness, or efficiency (IOM, 2013). In the traditional fee-for-service model of health care payment, providers are paid according to the number and type of health care services they provide. This approach to payment can incentivize unnecessary procedures and duplicative services, contributing to avoidable waste and inefficiency. Further, treatments are frequently prescribed without enough consideration of the social, behavioral and environmental factors that are significant determinants of health (McGinnis and Foege, 1993; Mokdad et al., 2004; Cullen et al., 2012; Chetty et al., 2016; McGinnis et al. 2016). Although contributions vary across population groups, medical treatment has a relatively small effect on the overall health and well-being of the population with shortfalls in medical care accounting for only about 10% of premature deaths overall, while behavioral patterns, genetic predispositions, social circumstances, and environmental exposures account for roughly 40%, 30%, 15%, and 5% of early deaths respectively (see Figure 5 (McGinnis et al., 2002). Yet, most health expenditures are devotedly exclusively to treatment.

With evidence mounting, it is becoming better understood that achieving better care and better value requires more active engagement of these broader factors in the care process and beyond.

To further advance value-based care, policy reforms should:

- Drive health care payment innovation providing incentives for outcomes and value. New payment and delivery models are being introduced that aim to reduce waste, increase value, and improve outcomes by advancing tailored, coordinated, and integrated care. Population-based payment models—the most comprehensive among alternative payment models—hold providers accountable for delivering patient-centered care for a designated population over a specified timeframe and across the entire spectrum of care (Mitchell, 2016). For providers to deliver care in this way, strong financial incentives must be in place, which require payers (beyond Medicare and Medicaid) to support and carry out payment reforms. Transition to value-based and population-oriented payment models will require different approaches to structuring economic rewards for population-wide progress, and well as harmonized measures used to assess results and reward accountability for system-wide performance (McClellan et al., 2016).

- Help clinicians develop the core competencies required for new payment models. More evidence is needed not only on the features and elements that determine the success of certain payment models, but which core competencies providers need to be successful in payment models. Evidence is accumulating in these areas but is spreading slowly. More timely and efficient evaluations of successful models are needed for Medicare payment reform pilots, as well as those being implemented in public and private programs (McClellan et al., 2016). Further, increased support and greater participation in public-private collaborations would be very helpful for providers in identifying the core competencies they need to succeed (Leavitt et al., 2016).

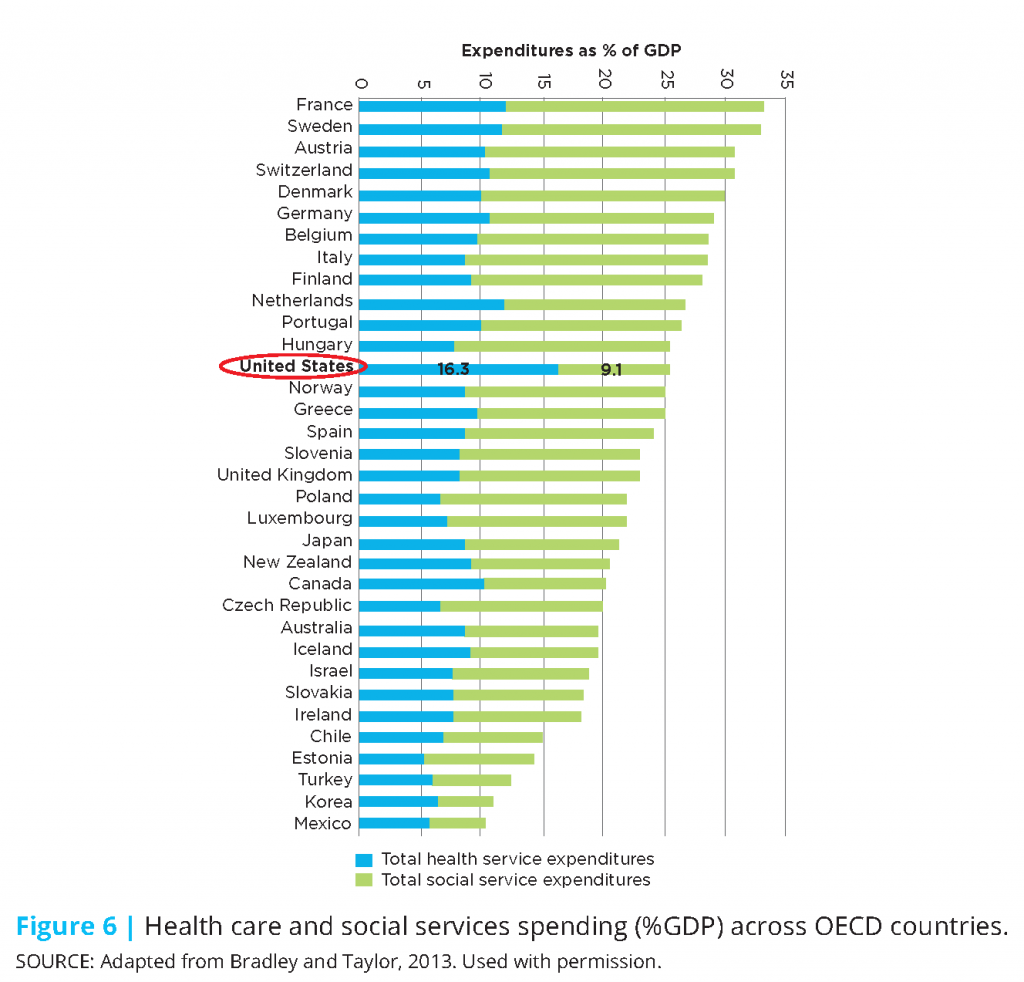

- Remove barriers to integration of social services with medical services. There is mounting evidence that U.S. under-investments in social services relative to health care services may be contributing to the country’s poor health performance (Bradley et al., 2011; Bradley and Taylor, 2013; IOM and NRC, 2013). Integrating clinical care services and nonmedical services (such as, housing, food, transportation, and income assistance), combined with some reinvestment of existing health care dollars into social services has great potential to achieve better outcomes, reduce inequality, and increase cost savings (Taylor et al., 2015). Although more research is needed to better understand the policy, payment, and regulatory options that could facilitate integration, some private health systems and health plans are already well positioned to pilot more of these efforts (Abrams et al., 2015).

Example policy initiatives from the Vital Directions discussion papers:

- Sustain and accelerate the implementation, demonstration, and assessment of alternative payment models supported by public and private health care payers to reward value and improve outcomes and health (McClellan et al., 2016).

- Reward measurement streamlining that helps identify and reward innovation and outcomes delivering value at system-wide and population levels (population-based payments) (McClellan et al., 2016).

- Support public-private collaborations among industry and government, e.g. the Accountable Care Learning Collaborative, which help clinicians and other provider groups identify and develop the core competencies necessary for success in the execution and use of alternative payment models (McClellan and Leavitt, 2016).

- Implement successful payment and delivery models for health and social services integration, e.g. funding stream integration so Medicaid managed care plans can coordinate with social and community interventions proven effective in improving outcomes and reducing costs (Adler et al., 2016).

Develop coordinated multi-agency strategies at the federal, state, and local levels to demonstrate the scale and spread of models that successfully link and deliver integrated health and social services.

Empower People – Democratize Action for Health

Ensure that people, including patients and their families, are fully informed, engaged, and empowered as partners in health and health care choices, and that care matches well with patient goals.

Improving the patient experience, improving population health, and reducing the per capita cost of health care cannot be achieved without effectively engaging and empowering patients and families across the care continuum—in effect, the quadruple aim of health and health care. However, too frequently, patients are insufficiently involved in their own care decisions, sometimes resulting in care that does not take into account the greater context of their lives or their individual goals. To be effective, policy reforms must do more than simply achieve engaged patients—rather, reforms need to ensure that patients and their families are fully informed and able to participate as partners in determining outcomes and values for their own health and health care. Further, empowering individuals to lead their own health care decisions requires giving them ownership of their personal health data. Doing so would better enable individuals to use, act on, and obtain personal value from their health information (Krumholz et al., 1999).

To empower people, policy reforms should:

- Link care and personal context. Identifying the “best” or “most appropriate” treatment goes beyond health factors and measures alone. Health care regimens and treatments must not only be safe and efficacious, but must work in the context of the patient’s life and goals (Braddock et al., 2016; Covinsky et al., 2000; Turnbull et al., 2016; Legare and Witteman, 2013). Providers with their patients and the patients’ families need to engage in integrated assessments of clinical and social goals, and reach mutually agreed upon care decisions.

- Communicate in a way appropriate to literacy. Shared decision making relies on people’s ability to gain access to, process, and understand basic health information. Policy makers and health leaders should focus on increasing the amount of information available and making the information more understandable and useful for everyone. These actions will help foster trust and lead to a more actively involved and health-literate public.

- Promote effective telehealth tools. Telehealth technologies—ways of delivering health-related information or services through the internet, phone, and other methods—can increase patient access to medical care, particularly in remote or underserved areas, and reduce costs (Berman and Fenaughty, 2005; Hailey et al., 2002; Keely et al., 2013). State-by-state regulatory barriers inhibiting the adoption of these technologies should be reduced. These barriers include reimbursement ineligibility and variations and restrictions in state-by-state licensure rules, which prevent physicians from practicing medicine outside of the state(s) in which they were licensed (Tang et al., 2016).

- Ensure patient data access, ownership, and privacy. Individuals’ health information is stored in numerous, often siloed, locations, and most frequently in EHRs, from which data can been very difficult to access. Further, ownership of individuals’ health data is typically assigned to physicians and hospitals (Kish and Topol, 2015). Empowering individuals to make informed, personal health decisions requires giving them ownership of their own health data, and offering every assurance that their data are held privately and securely.

Example policy initiatives from the Vital Directions discussion papers:

- Develop incentives, along with clinical practice guidelines and decision support tools to encourage physicians to engage with each patient on their personal context and goals in making care decisions (Tang et al., 2016).

- Expand health literacy services to ensure that information, processes, and delivery of health care in all settings align with the skills and abilities of all people.

- Support patient communication research on and decision-making strategies to determine the most effective approaches to relaying information on care, cost, and quality (Pronovost et al., 2016). For example, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Communication and Dissemination Research program, focusing on approaches to communicate and disseminate health information and research findings to patients (PCORI, 2017).

- Harmonize telemedicine reimbursement standards across payers, and establish common national licensure for telehealth practitioners, so that telehealth clinicians may provide services across state lines (Tang et al., 2016).

Activate Communities – Collaborate to Mobilize Resources for Health Progress

Equip and empower communities to build and maintain conditions that support good health, link health and social services where possible, and identify and respond to health threats locally.

Health is rooted in communities, where people live, work, eat, learn, and play—a person’s ZIP code is perhaps the strongest predictor of health outcomes and life expectancy (RWJF, 2009; Heiman and Artiga, 2016). Related, a person’s health is very much a product of the available social supports within their community, their surrounding physical environment and local characteristics, and personal behavior, which is highly influenced by these factors. In this way, while some communities are healthy and thriving, others are struggling, as reflected in the widening gap in lifespans between the rich and poor (NASEM, 2015; Chetty et al., 2016), and persisting discrepancies in quality and health care access between urban and rural areas (Stanford School of Medicine, 2010). Underscoring the potential for community-driven initiative to effect social and cultural change, a recent report from the National Academies examined efforts in 9 communities to address social, economic, or environmental health determinants, finding that, with the right mix of evidence-based attention to growing community capacity, and multi-sectoral collaboration, communities can put forward solutions to promote health equity (NASEM, 2017). However, when comparing relative investments in health care and social services, the U.S. continues to invest far less in community-based social services than its peers (Bradley and Taylor, 2013) (See Figure 6).

Communities have essential roles to play in combating the nation’s most pressing health threats, such as the chronic disease and substance abuse epidemics. If activated with the sufficient resources and capacity, community health leaders—health care organizations, hospitals, municipal public health departments, and community standards-setting agencies—are capable of driving critical change by promoting healthy environments and behaviors, and by fostering a culture of continuous health improvement (Goldman et al., 2016). To be successful, community solutions require a supportive policy and resource environment to facilitate community efforts.

To activate communities, policy reforms should:

- Invest in local leadership and infrastructure capacity for public health initiatives. Transformative change in health and health care requires a culture shift spearheaded by leadership and action within communities. Notably, achieving optimal health for all will necessitate a “Health in All Policies Approach,” including collaborations and support from leaders in all sectors, such as business, education, housing, and transportation, in defining and achieving health goals. Buy-in should be built on the premise that all sectors have an interest in creating and sustaining livable communities that are healthy, thriving, and prosperous.

- Expand community-based strategies targeting high-need individuals. High-need patients are typically among the sickest, with multiple comorbidities and the most complex health needs. These individuals constitute about 5% of all patients but drive roughly 50% of health care costs (Mitchell, 2016) (see Figure 7). Achieving better health outcomes and greater efficiency within this patient segment requires close coordination and integration of medical and social services. Expanded community-based strategies are needed to ensure that high-need, high-cost individuals receive the social supports essential to the success of their health care and health outcomes, including food, housing, transportation, and income assistance. Ultimately, close links between health care and community-based services will be essential to achieving better health outcomes and greater system efficiency.

- Provide strong state-based capacity for guidance, assistance, and synergy for local health efforts. States are often considered the “laboratories” for health and health care, and should be looked to as a resource to scale existing community health innovations. Useful case examples and best practices should be identified and disseminated for other communities to learn from and tailor for their own purposes.

Example policy initiatives from the Vital Directions discussion papers:

- Strengthen local level infrastructure and capacity for multi-sectoral health initiatives, using resources marshaled from federal grant programs, tax incentives, health insurance payments linked to population health, and public-private partnerships (Goldman et al., 2016). For example, require that tax-exempt health organizations meeting IRS requirements for community benefit work through coordinated community-wide public-private partnerships and multi-sectoral initiatives.

- Invest in the nation’s physical infrastructure with an eye on health. For example, a multi-sectoral strategy targeting jurisdictions with older physical infrastructures to assess infrastructure weak spots and to facilitate with community structural improvements—leveraging not only health assets but labor, housing, transportation, and other relevant department efforts.

- Support states’ flexible use of grant funds to provide guidance, technical assistance, and strategic resources for local leadership and collaborative action to identify and target their most important health challenges (Goldman et al., 2016).

- Identify best practices from pilot programs launched through Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) on approaches linking relevant health, education, social service, and legal system activities and resources to address individuals at highest risk and with the greatest needs (Goldman et al., 2016; Adler et al., 2016).

- Give states flexibility to use Medicaid funds to implement best practices in targeting the most effective efforts for high-risk, vulnerable children (e.g., prenatal to 3), as well as adults at particular risk with complex, multifactorial conditions (McGinnis et al., 2016; Adler et al., 2016).

Connect Care – Implement Seamless Digital Interfaces for Best Care

Develop standards, specifications, regulatory policies, and interfaces to ensure that patient care data and services are seamlessly and securely integrated, and that patient experience is captured in real-time for continuous systemwide learning and improvement.

Health information technology (HIT) has had tremendous impact on health care, driving greater accountability and value, enhanced public engagement and purpose, improved public health surveillance, and more rapid development and diffusion of new therapies. Yet critical challenges remain, including the ability of providers to amass and share electronic health record (EHR) data for individual patients longitudinally, which is essential to harnessing the economic and clinical benefits of EHRs (Perlin et al., 2016). Despite the rapid advancement and broadening technical capacity of digital technology for health, digital interoperability—the extent to which systems can share and make use of data—remains extraordinarily limited. The consequences are adverse in several ways: care continuity between clinicians and over time is impeded; gaps and duplications in efforts are undiscovered; device incompatibility predisposes to patient harm, clinician stress is compounded, and end-user costs are higher as systems try to cobble together temporary fixes. Interoperable information technology and generated data are foundational to the promise of a continuously learning health system, in which data are continuously contributed, shared, and analyzed to support better health, more effective care, and better value.

To achieve connected care, policy reforms should:

- Make necessary infrastructure and regulatory changes for clinical data accessibility and use. Specific infrastructure and regulatory barriers exist to clinical data accessibility and use that require attention and remediation. Among the most critical are: specifications for data that have been developed but not adopted; commercially protective coding practices; proprietary data ownership and use restrictions; and misinterpretation of control requirements for use of clinical data as a resource for new knowledge. The recently passed 21st Century Cures Act does include provisions to encourage and facilitate sharing and use of clinical data, but those provisions will still require local action and leadership.

- Create principles and standards for end-to-end interoperability. Either through federally-facilitated or mandated efforts, or through direct federal action, specific standards need to be supported for end-to-end (system/clinician/patient) interoperability, so as to allow private and secure data transmission among EHRs and FDA-approved medical devices, and to provide a path toward data exchange with consumer health technologies.

- Identify information technology and data strategies that support continuous learning. The technical capacity exists for continuous communication and learning throughout health care, ranging from the activities of different clinicians and institutions, to the operation and interplay among relevant medical devices, to readings from mobile biomonitoring devices. Taking full advantage of this transformative capacity requires comprehensive strategy and action to strengthen data infrastructure, build public trust around data privacy and security, and harmonize inconsistent state and local policies on data use and sharing.

Example policy initiatives from the Vital Directions discussion papers:

- Use HHS regulatory and reimbursement mechanisms to enforce existing interoperability standards for interoperability across EHRs and medical devices (Perlin et al., 2016).

- Support a voluntary national patient identifier whereby patients could opt-in to be assigned a unique identification number, which would facilitate patient-data matching, as well as overall data aggregation (Perlin et al., 2016).

- Continue escalation of EHR use as a condition of participation in federal health care programs, such as Medicare, to better allow understanding of national disease burden, health resource planning, and auditing for prevention of fraud, waste, and abuse (Perlin et al., 2016).

- Through HHS, sponsor a public-private standards organization to commission the necessary additional standards, e.g. open, standardized application programming interfaces (APIs) to support continuously improving standardized service-oriented architecture for interoperability and clinical decision support.

- Streamline inconsistent state and local security and privacy policies related to data exchange and use (e.g., federal guideline enabling states and localities to harmonize data use policies and reciprocal support agreements). Simultaneously, consider safe harbor provisions against civil penalties for data sponsored attacks and “hacktivists” (Perlin et al., 2016).

- Building on the principle of patient ownership of data, foster active patient access and use of their own data for care and evidence improvement (Krumholz et al., 2016).

Essential Infrastructure Needs

Successful engagement of these action priorities and their considerable potential for progress requires the simultaneous pursuit of four essential infrastructure needs: measure what matters most, modernize skills, accelerate real-world evidence, and advance science. The significance of these essential infrastructures is clear. At population, community, and individual levels, the pace of health progress will depend on effective measures that can drive better understanding and action focused on the issues that matter most in health and health care. Modern skillsets for the health care workforce will be necessary to provide integrated care for an increasingly complex patient population. Similarly, new training approaches and skills for the biomedical workforce will be needed to realize the most cutting-edge research and technological advancements that will support innovative care. Related, continued innovation in tools and approaches for improving health and health care will require taking advantage of expanding capacities to learn, collect and share real-world clinical data. Finally, sustained investment in scientific research combined with streamlined regulatory pathways will enable more rapid translation of the most effective and promising medical treatments and tools that will help drive better health outcomes.

Measure What Matters Most – Use Consistent Core Metrics to Sharpen Focus and Performance

Standards, specifications, and governance strategies should be developed to accelerate the identification, refinement, harmonization, and implementation of a parsimonious set of core measures that 1) best reflect national, state, local, and organizational system performance on issues that matter most to health care, and 2) guide the development of related measures, not for reporting but for quality improvement.

Within the past two decades, greater demand for accountability and information on system performance has translated into the proliferation of performance measures and related data. While performance measurement and public reporting have been beneficial to increasing system accountability and performance, concerns are growing about the time, cost, validity, generalizability, and overall burden of clinical measurement (Pronovost et al., 2016). For example, performance measures are often produced and applied by numerous organizations in a variety of ways, creating inconsistencies and reducing the measures’ value and usefulness. And while it is critical to be transparent by reporting outcomes and performance, the results become meaningless if the measure and its application lack validity, reliability, and generalizability. Further, as the volume of performance measures becomes burdensome and time-consuming for providers, measurement reporting has the unintended effect of driving up costs and adding to existing inefficiencies.

To achieve meaningful measurement, policy reforms should:

- Focus reliably and consistently on factors most important to better health and health care. A standard set of core measures, available at national, state, local, and institutional levels, would offer benchmarks for targeting and assessing problems and interventions, as well as providing baseline reference points to improve the reliability of broader measurement, evaluation, accountability, and research efforts. The National Academies report

Vital Signs presents a framework for 15 such measures of health, care quality, value, engagement, and public communication (IOM, 2015a). - Create the national capacity for identifying, standardizing, implementing and revising core measures. On the assumption that measures employed as a baseline multi-level performance assessment instrument should be developed, tested, and refined through a broad independent process involving multiple stakeholders, the Vital Signs committee recommended that the Secretary of Health & Human Services identify a lead organization for each of the 15 core measures, which would, in turn, engage related stakeholder organizations in the refinement process. The Committee also recommended creating an ongoing, independent capacity to guide and oversee the revision process longterm.

- Invest in the science of performance measurement. Currently, there is no consensus on how best to measure care delivery and performance. More research is needed on the development of performance measures, including how to create and maintain a standardized, scientific approach to performance measurement (Pronovost et al., 2016).

Example policy initiatives from the Vital Directions discussion papers:

- Initiate HHS process to refine and implement the Vital Signs core measures nationally, beginning with the federal categorical and health care funding programs, including a variation to be used by states in return for Medicaid management flexibility (McGinnis et al., 2016).

- Provide waivers from Medicare reporting requirements for health care organizations working in multi-organization collaboratives to implement and report on core system-wide performance measures (McGinnis et al., 2016).

- Through an initiative or taskforce, explore the design of an independent, standards-setting body for reports on health care performance measures. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) could be referenced as a model—the FASB establishes financial accounting and reporting standards for companies and non-profit organizations (Pronovost et al., 2016).

- Create a multi-agency, collaborative research initiative on the science of performance measurement, including how best to develop, test, evaluate and improve measures (Pronovost et al., 2016).

Modernize Skills – Train the Workforce for 21st-Century Health Care and Biomedical Science

Foster modern skillsets through integrated and innovative education and training approaches that can meet the rapidly evolving demands of health care, biomedical science and industry.

Ensuring the talent and motivation of the nation’s human capital pool is a central determinant of national competitiveness (Zerhouni et al., 2016). Investing in and strengthening the capacity of our health care and biomedical science workforces is critical to our nation’s health, economic and physical security, and global leadership in research and innovation. But new directions in training are needed. The health care workforce of the 21st century must be able to effectively manage and treat increasingly complex patient and population health profiles and circumstances, particularly with a rapidly aging population and rising burden of chronic disease. Simultaneously, health care workers must be adept at keeping healthy patients healthy through preventive therapies and guidance, while harnessing and applying rapidly advancing health information technology and innovation. Supporting the biomedical science workforce of the 21st century will also require modern education and training approaches. Existing training models and pathways are outdated and fragmented (Kruse, 2013), have become longer and more expensive, and no longer assure stable, successful careers (Zerhouni et al., 2016).

To modernize skills, policy reforms should:

- Reform health care education and training approaches to meet our nation’s complex health needs. For the health care workforce, adapting training and practice to coordinated team-based approaches is essential to care delivery in our ever-evolving and complex care environment. To deliver efficient and high-quality care, a next generation health care workforce needs to be recruited, educated, and trained to work collaboratively in interdisciplinary teams, become technically skilled, and be facile with the full use of health information technology (Lipstein et al., 2016). In particular, clinical workforce skills and capabilities will need to evolve and advance alongside the rapid innovations in HIT. In addition to using information technology, health care practitioners will need to understand how the data are collected, analyzed, and applied. To facilitate, informatics requirements should be integrated into existing graduate medical education (GME) and training programs, including the federal GME program.

- Create and support new education and training pathways for the science workforce. Training the science workforce for the future will require new models, new partners, and cross-disciplinary thinking. Our new workforce will need to be diverse, multidisciplinary, team-oriented, and possess strong skills in data analytics and informatics. Recruiting and retaining the most talented will necessitate innovative education pathways and programs to assemble and support a cutting-edge biomedical science workforce.

Example policy initiatives from the Vital Directions discussion papers:

- Engage the scientific community, private foundations, state higher education officials, federal health professions payers in proposing a public-private national initiative on health professions education that is team-based, collaborative, multidisciplinary, and skilled in HIT and informatics (Lipstein et al., 2016).

- Leverage eligibility requirements for Medicare alternative payment models to require that providers include a description of their plans for augmented use of systems engineers and HIT coaching and expertise (Perlin et al., 2016).

- Launch a visible, high-level initiative to attract the most talented students and researchers into biomedical research careers (e.g. a NextGen Opportunity Fund, as described by Zerhouni et al., 2016).

Accelerate Real-World Evidence – Derive Evidence from Each Care Experience

Accelerate clinical research that enlists patients as partners, takes advantage of big data, and collects real-world data on care or program experience for continuous learning, improving, and tailoring of care.

Harnessing the full power of a learning health system will remain more an aspiration than a consistent achievement until fully leveraging available data becomes a practical possibility (Krumholz, 2016). The existing ability to collect enormous swaths of real-world, clinical and health-related data holds immense promise for improving clinical care by better informing clinical choice, improving drug and medical device safety, effectiveness assessment, and scientific discovery. However, technical, regulatory, and cultural barriers to harnessing these data for societal benefit persist— notably, an outdated clinical research paradigm and inadequate data-sharing incentive structure. With respect to the latter, data-sharing is neither simple, nor an established norm in health care and clinical research. In fact, much of the data generated over the course of a clinical trial is never published or made easily accessible (IOM, 2015b).

Related to clinical research, the complexity of many medical products being developed today is exceeding traditional evaluation models, such as randomized clinical controlled trials (RCTs). Roughly 85% of therapies fail early during clinical development, and of those that survive phase III trials, about 50% actually get approved (Ledford, 2011). The traditional paradigm of clinical research that was instituted in the 1960s was based on single trials that occurred at one site, and were designed to answer one question. Today, trials are much larger, occurring in multiple sites, and seeking to solve more complex problems. RCTs, while still the gold standard of clinical research, can be limited in their generalizability and ability to reflect real-world results. And, as we enter the era of precision medicine, RCTs alone will be unable to produce enough data to support this new paradigm (BPC, 2016). Alongside RCTs, learning health system models of evaluation are emerging that use real-world evidence (or digital health information) captured in EHRs and other digital platforms that continuously collect and distribute clinical data. The recent 21st Century Cures Act includes provisions supporting the inclusion of real-world evidence in approving new indications for drugs. Demonstrative real-world evidence combined with the rigor of clinical trial data could yield important and powerful opportunities to enhance care and improve outcomes.

To accelerate reliable evidence, policy reforms should:

- Advance continuous learning clinical research drawing on real-world evidence. Complementing controlled studies, the ability to collect data from clinical practice presents a great opportunity to gain new, possibly more accurate insights about the efficacy and safety of drugs and medical devices. These data could offer nuanced information and findings that would be otherwise unattainable in a standard RCT. Beyond complementing traditional RCTs, initial applications of clinical practice data could include testing supplemental applications of approved medicines. In the future, select pilots could be pursued using a continuously learning

approach to evaluate real-world evidence in both pre-approval and post-approval contexts (Rosenblatt et al., 2016). - Foster a culture of data sharing by strengthening incentives and standards. As with routine clinical data, research participants should have presumptive ownership and the right to access and share their own health information. In addition, researchers should more broadly accept that strong science and “good scientific citizenship” require individual-level data to be more accessible for evaluation and reuse, with the necessary safety and privacy precautions in place (Krumholz et al., 2016). For data sharing to become a more accepted norm, a cultural shift in health care might be facilitated through financial and professional incentives, as well as strengthened standards for data ownership and sharing protocols.

- Partner with patients and families to support evidence generation and sharing. Partnering with patients, and simultaneously taking steps to better ensure their privacy and trust, is a prerequisite to effective evidence generation and data sharing for care improvement and learning. Engaging patients throughout the research process can help identify unmet care needs, future research priorities, and help realize better clinical outcomes. Initiatives on patient engagement should address how best to incorporate patient input; how to effectively build patient skillsets for engagement; and how to define value, so that it better reflects the patient perspective (Rosenblatt et al., 2016).

Example policy initiatives from the Vital Directions discussion papers:

- Support public-private partnerships to build on existing pilot studies to assess and expand real-world evidence development in both pre-approval and post-approval settings (Rosenblatt et al., 2016).

- Continue to promote and harmonize federal standards relevant to data-sharing, as well as to ownership, security, and privacy of health-care data (Krumholz et al., 2016).

- Incentivize data-sharing; for example, create a reimbursement benefit for health systems that facilitate data access and sharing between patients and researchers (Krumholz et al., 2016).

- Establish initiatives to build patient skill-sets for engagement. In addition, better define value in terms that reflect the patient perspective, and assess and identify measures for patient trustworthiness and participation (Dzau et al., 2016).

Advance Science – Forge Innovation-Ready Clinical Research Processes and Partnerships

Redesign training, financial support, and research and regulatory policies to enable and encourage transformative innovation in science and its translation.

The United States has long been at the forefront of biomedical science and innovation, but in recent years, its lead has been challenged by rising competition from other countries. Cumbersome and outdated regulatory review processes are making it more difficult to bring promising therapies and devices to market. In addition, the cost of drug and device development has risen substantially—some estimate the cost of bringing a new drug to market to be $2.6 billion (TSCDD, 2015). The slowing pace and rising cost of biomedical innovation are fueling calls for new discovery, development, production, and commercialization models (Rosenblatt et al., 2016), as well as more collaborative partnerships capable of driving rapid innovation.

To advance the pace of innovation, policy reforms should:

- Promote the conditions for scientific innovation. Advancing science first and foremost requires investment. Necessary conditions for success are commitment to funding and support for basic and applied research, and the acceleration in translation. Furthermore, taking advantage of datasets rapidly growing to very large sizes, new forms of science, technology, and evidence development can boost clinical care research. Opportunities include making greater use of real-world evidence and cognitive computing to better understand and ensure the most effective and appropriate interventions for the best possible clinical outcomes (Rosenblatt et al., 2016).

- Support an adaptive and patient-oriented regulatory framework. Outdated models of discovery, development, and approval need to be adapted to a more forward-looking paradigm promoting efficiency, continuous innovation, and patient centricity. Recent efforts by the FDA to implement expedited regulatory approval tracks represent good progress, but other opportunities to improve efficiency exist. Aligning discovery and development with current needs will require patient input and partnership in all stages of research and development; multidisciplinary, cross-sector collaborations to achieve needed breakthroughs in combating

complex diseases; more efficient clinical trials with adaptive designs; and greater experimentation with and use of real-world evidence, in addition to data produced during RCTs. - Foster cross-disciplinary and public-private partnerships. Existing siloes across disciplines and sectors are counterproductive to progress. Greater collaboration among scientists in the government, academia, and industry is needed to advance innovation. Cross-disciplinary partnerships will be essential, with basic scientists, translational scientists, and clinical scientists working together to achieve breakthroughs in the most challenging therapeutic areas, including autoimmune, neurodegenerative, and inflammatory diseases (Rosenblatt et al., 2016).

Example policy initiatives from the Vital Directions discussion papers:

- Ensure research funding for basic and applied sciences.

- Support public-private programs to invest in and advance the science and related applications of big data analysis, such as cognitive computing (Rosenblatt et al., 2016).

- Develop and apply a strategy for engaging patients as active partners in the advancement of innovative approaches to clinical research, including their support for expanded use of clinical data for discovery and for appropriate communication and experience feedback between industry and patients throughout the discovery and development processes (Rosenblatt et al., 2016).

- Support precompetitive collaborations including industry, government, and academia—such as the Accelerating Medicines Partnership—to achieve needed breakthroughs in the most challenging therapeutic areas that cannot be done by any sector alone (Rosenblatt et al., 2016), such as the Accelerating Medicines Partnership (NIH, 2017).

The Path Forward

Despite the intense debate that surrounds many health policy issues today, we have found strong agreement on the critical challenges as well as the vital directions required to achieve progress. As policymakers consider the next chapter of health reform, no matter the fate of the ACA, the priority actions and essential infrastructures identified here represent the basic principles around which we can attain better health and well-being, higher-value care, and the strong science and innovation that will drive better health outcomes, efficiency and quality. In particular, we see substantial prospects if we can capture the potential from greater empowerment of people in their care processes; activate communities to promote and sustain the health of their residents; harness the potentially transformative connectivity of our digital infrastructure; and accelerate the movement toward a payment system based on value and results. Just a decade ago, these strategic prospects were scarcely more than conceptual notions, but today we see evidence of their promise, including the essential infrastructures needed to support them.

The potential for progress hinges on strong leadership at all levels—organizational, local, state, and federal—as well as strategic investment across these priorities. At the federal level, leadership opportunities exist on multiple fronts: creating and supporting program partnerships that enhance the flexibility of state and local leaders to rally community-wide engagement around agreed upon priorities and targets; developing public-private stakeholder groups working together on strategies, benchmarks, training, and resources; introducing accountability measures and tracking that focus on results rather than processes; and offering flexibility and incentives for cross-sector alliances and activities.

Similarly, leadership at the state and local levels is vital to ensure that individual communities are healthy, thriving, and promoting the strength of the cooperative community-wide initiatives important to progress. As noted earlier, health begins where people live, work, eat, learn, and play. Community-led programs and initiatives are critical to identifying and mitigating socioeconomic and environmental factors that contribute to health disparities; developing models and best practices for preventing disease; creating health-promoting infrastructure and local environments; and mitigating some of our most pressing health threats. Beyond strong leadership, strategic investment of existing resources across the priorities indicated will be required to achieve the better outcomes we have long sought. As a nation, we have the world’s largest observable discrepancy between the amount spent on health care and the impact of that expenditure on the nation’s health—but we are poised with real prospects for improvement, if we deploy our resources wisely. And, if we can redirect even a relatively small portion of the approximately $1 trillion now spent unnecessarily on health care to the high-priority investment opportunities described here, the health and productivity benefits will extend far beyond the health sector. Notably, prioritizing our nation’s health through strong leadership and strategic investment will yield greater prosperity, security, global leadership and competitiveness for the country. These are vital directions for every American.

APPENDIX A: Paper Topics, Authors, and Summary Recommendations

Better Health and Well-Being

Systems Strategies for Better Health Throughout the Life Course

Authors: J. Michael McGinnis, National Academy of Medicine; Don Berwick, Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Tom Daschle, Former U.S. Senator, The Daschle Group; Angela Diaz, Mount Sinai; Harvey Fineberg, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation; Bill Frist, Former U.S. Senator, Bipartisan Policy Center; Atul Gawande, Ariadne Labs, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Harvard University; Neal Halfon, University of California, Los Angeles; and Risa J. Lavizzo-Mourey, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Shift health care payments to financing that rewards system-side health improvement.

- Initiate multi-level standardized measurement of system performance on core health indices.

- Speed development of a universally accessible and interoperable digital health platform.

- Foster awareness and action on a community culture of continuous health improvement.

Addressing Social Determinants of Health and Health Disparities

Authors: Nancy E. Adler, University of California, San Francisco; David M. Cutler, Harvard University; Jonathan E. Fielding, University of California, Los Angeles; Sandro Galea, Boston University; M. Maria Glymour, University of California, San Francisco; Howard K. Koh, Harvard University; and David Satcher, Morehouse School of Medicine

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Strengthen assessment and action on health-impacting social policies.

- Expand policies that increase resources and environments fostering healthy behaviors.

- Extend the reach and transform the financing of health care services.

Preparing for Better Health and Health Care for an Aging Population

Authors: Jack W. Rowe, Columbia University; Lisa Berkman, Harvard University; Linda Fried, Columbia University; Terry Fulmer, John A. Hartford Foundation; James Jackson, University of Michigan; Mary Naylor, University of Pennsylvania; William Novelli, Georgetown University; Jay Olshansky, University of Illinois at Chicago; and Robyn Stone, LeadingAge

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Develop new models of care delivery.

- Augment the elder care workforce.

- Promote the social engagement of older persons.

- Transform advanced illness care and care at the end of life.

Chronic Disease Prevention: Tobacco, Physical Activity, and Nutrition for a Healthy Start

Authors: William H. Dietz, George Washington University; Ross C. Brownson, Washington University; Clifford E. Douglas, American Cancer Society; John J. Dreyzenher, Tennessee Department of Health; Ron Z. Goetzel, Truven Health Analytics; Steven L. Gortmaker, Harvard T.H. School of Public Health; James S. Marks, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Kathleen A. Merrigan, George Washington University; Russell R. Pate, University of South Carolina; Lisa M. Powell, University of Illinois at Chicago; and Mary Story, Duke University

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Strengthen federal efforts to reduce use by youth of all nicotine-contain¬ing products, through excise tax increases and the regulatory process.

- Provide incentives for states and local school districts to adopt the Com¬prehensive School Physical Activity Program model.

- Fully apply the standards in the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act to the National School Lunch Program, the School Breakfast Program, and to the foods and beverages sold in schools.

Improving Access to Effective Care for People Who Have Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders

Authors: James Knickman, New York University; K. Ranga Rama Krishnan, Rush University Medical Center; Harold A. Pincus, Columbia University; Carlos Blanco, National Institutes of Health; Dan G. Blazer, Duke University Medical Center; Molly J. Coye, AVIA; John H. Krystal, Yale University School of Medicine; Scott L. Rauch, McLean Hospital; Gregory E. Simon, Group Health Research Institute; and Benedetto Vitiello, National Institute of Health

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Implement payments models that support service integration.

- Train a workforce skilled in managing mental health and substance abuse in the context of integrated care.

- Develop incentives to disseminate tested organizational models and create new approaches

Advancing the Health of Communities and Populations

Authors: Lynn Goldman, George Washington University; Georges Benjamin, American Public Health Association; Sandra Hernández, California Health Care Foundation; David Kindig, University of Wisconsin; Shiriki Kumanyika, University of Pennsylvania; Carmen Nevarez, Public Health Institute; Nirav R. Shah, Kaiser Permanente; and Winston Wong, Kaiser Permanente

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Implement payments models that support service integration.

- Train a workforce skilled in managing mental health and substance abuse in the context of integrated care.

- Develop incentives to disseminate tested organizational models and cre¬ate new approaches

High-Value Health Care

Benefit Design to Promote Effective, Efficient, and Affordable Care

Authors: Michael E. Chernew, Harvard Medical School; A. Mark Fendrick, University of Michigan; Sherry Glied, New York University; Karen Ignagni, EmblemHealth; Steve Parente, University of Minnesota; Jamie Robinson, University of California, Berkeley; and Gail Wilensky, Project HOPE

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Modify safe-harbor regulations for HSA-HDHP plans to permit first-dollar coverage of high-value services.

- Standardize plans offered on the exchange to incorporate principles of value-based insurance design.

- Redesign the Medicare benefit package.

- Limit the favorable tax treatment of insurance.

Payment Reform for Better Value and Medical Innovation

Authors: Mark McClellan, Duke University; David Feinberg, Geisinger Health System; Peter Bach, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; Paul Chew, Sanofi; Patrick Conway, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Nick Leschly, Bluebird; Greg Marchand, Boeing; Michael Mussallem, Edwards Biosciences; and Dorothy Teeter, Washington Health Care Authority

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Align the implementation of payment reform with provider efforts to improve quality and value.

- Address and incorporate costly but potentially life-saving technologies.

- Ensure that payment reform does not exacerbate adverse consolidation and market power.

- Conduct more timely and efficient evaluations of what is working.

Competencies and Tools to Shift Payments from Volume to Value

Authors: Michael O. Leavitt, Former Governor of Utah, Leavitt Partners; Mark McClellan, Duke University; Susan D. DeVore, Premier, Inc.; Elliott Fisher, Dartmouth College; Rick Gilfillan, Trinity Health; H. Steve Lieber, Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society; Richard Merkin, Heritage Provider Network; Jeffrey Rideout, Integrated Healthcare Association; and Kent J. Thiry, DaVita Healthcare Partners, Inc.

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Promote and improve the design of value-based payment.

- Increase the flexibility of accountable providers to pay for nonmedical services.

- Provide intensive technical assistance to providers regarding care for HNHC patients.

- Give high priority to health information exchange.

- Continue active experimentation to accelerate the spread and scale of evidence-based practices.

Tailoring Complex Care Management, Coordination, and Integration for High-Need, High-Cost Patients

Authors: David Blumenthal, The Commonwealth Fund; Gerard Anderson, Johns Hopkins University; Sheila Burke, Harvard John F. Kennedy School; Ashish K. Jha, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Terry Fulmer, John A. Hartford Foundation; and Peter Long, Blue Shield of California Foundation

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Promote and improve the design of value-based payment.

- Increase the flexibility of accountable providers to pay for nonmedical services.

- Provide intensive technical assistance to providers regarding care for HNHC patients.

- Give high priority to health information exchange.

- Continue active experimentation to accelerate the spread and scale of evidence-based practices.

Realizing the Full Potential of Precision Medicine in Health and Health Care

Authors: Victor J. Dzau, National Academy of Medicine; Geoffrey S. Ginsburg, Duke University; Aneesh Chopra, Hunch Analytics; Dana Goldman, University of Southern California; Eric D. Green, National Institutes of Health; Debra G.B. Leonard, University of Vermont; Mark McClellan, Duke University; Andy Plump, Takeda Pharmaceuticals; Sharon F. Terry, Genetic Alliance; and Keith R. Yamamoto, University of California, San Francisco

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Develop evidence of precision medicine’s effect.

- Accelerate clinical data integration and assessment.

- Promote integration of molecular guidance into care.

- Develop innovation-oriented reimbursement and regulatory frameworks.

- Strengthen engagement and trust of the public.

Fostering Transparency in Outcomes, Quality, Safety, and Costs

Authors: Peter J. Pronovost, Johns Hopkins Medicine; J. Matthew Austin, Johns Hopkins Medicine; Christine K. Cassel, Kaiser Permanente School of Medicine; Suzanne F. Delbanco, Catalyst for Payment Reform; Ashish K. Jha, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Bob Kocher, Venrock; Elizabeth A. McGlynn, Kaiser Permanente; Lewis G. Sandy, UnitedHealth Group; and John Santa, formerly Consumer Reports

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Create a health measurement and data standard-setting body.

- Build the science of performance measures.

- Improve the communication of data to patients.

Democratization of Health Care

Authors: Paul C. Tang, IBM Watson Health; Mark D. Smith, University of California, San Francisco; Julia Adler-Milstein, University of Michigan; Tom Delbanco, Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center; Stephen J. Downs, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Giridhar G. Mallya, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Debra L. Ness, National Partnership for Women & Families; Ruth M. Parker, Emory University; and Danny Z. Sands, Conversa Health

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Focus health financing on health.

- Measure what matters most to people.

- Include needed social services and health literacy in health financing.

- Streamline access to validated telehealth tools.

Workforce for 21st Century Health and Health Care

Authors: Steven H. Lipstein, BJC HealthCare; Arthur L. Kellermann, Uniformed University of the Health Sciences; Bobbie Berkowitz, Columbia University; Robert Phillips, American Board of Family Medicine; Glenn D. Steele, Jr., xG Health Solutions; David Sklar, University of New Mexico; and George E. Thibault, Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Assess and ensure the sufficiency of the frontline health care workforce.

- Ensure an acute care workforce that can provide timely accessibility.

- Develop the clinical and social service teams required to manage high-need chronic conditions.

- Train the caregiver workforce so important at the end of life.

Strong Science and Technology

Information Technology Interoperability and Use for Better Care and Evidence

Authors: Jonathan B. Perlin, Hospital Corporation of America; Dixie B. Baker, Martin Blanck, and Associates; David J. Brailer, Health Evolution Partners; Douglas B. Fridsma, American Medical Informatics Association; Mark E. Frisse, Vanderbilt University; John D. Halamka, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; Jeffrey Levi, George Washington University; Kenneth D. Mandl, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School; Janet M. Marchibroda, Bipartisan Policy Center; Richard Platt, Harvard University; and Paul C. Tang, IBM Watson Health

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

- Commit to end-to-end interoperability extending from devices to EHR systems.

- Aggressively address cyber security vulnerability.

- Develop a data strategy that supports a learning health system

Data Acquisition, Curation, and Use for a Continuously Learning Health System