Communicating with Patients on Health Care Evidence

Our aim is to accelerate the routine use of the best available evidence in medical decision making by raising awareness of and increasing demand for medical evidence among patients, providers, health care organizations, and policymakers. This paper is the product of individuals who have worked to develop principles and strategies to guide evidence communication among providers and patients, communication that holds the potential to yield better care, better health, and lower costs. The authors are participants drawn from the Evidence Communication Innovation Collaborative (ECIC) of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care, which seeks to improve public understanding, appreciation, and evidence-based discussion of the nature and use of evidence to guide clinical choices. The Collaborative is inclusive—without walls—and its participants include communication experts, decision scientists, patient advocates, health system leaders, health care providers, and more.

The Learning Health Care System and Evidence Communication

The charter of the IOM Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care envisions a learning health care system and states that “by the year 2020, 90 percent of clinical decisions will be supported by accurate, timely, and up-to-date clinical information, and will reflect the best available evidence.” A continuously learning health system can deliver truly patient-centered care only when patient preferences—informed by medical evidence and provider expertise—are elicited, integrated, and honored. Shared decision making is the process of integrating patients’ goals and concerns with medical evidence to achieve high-quality medical decisions. A 2011 Cochrane systematic review of 86 clinical trials found that patients’ use of evidence-based decision aids led to a) improved knowledge of options; b) more accurate expectations of possible benefits and harms; c) choices more consistent with informed values; and d) greater participation in decision making. [1] Providing patients with clearly-presented evidence has been shown to impact choices, resulting in better understanding of treatment options and screening recommendations, higher satisfaction, and choices resulting in lower costs. [2] Simply stated, engaging patients in their own medical decisions leads to better health outcomes. [3,4,5]

KEY FINDINGS

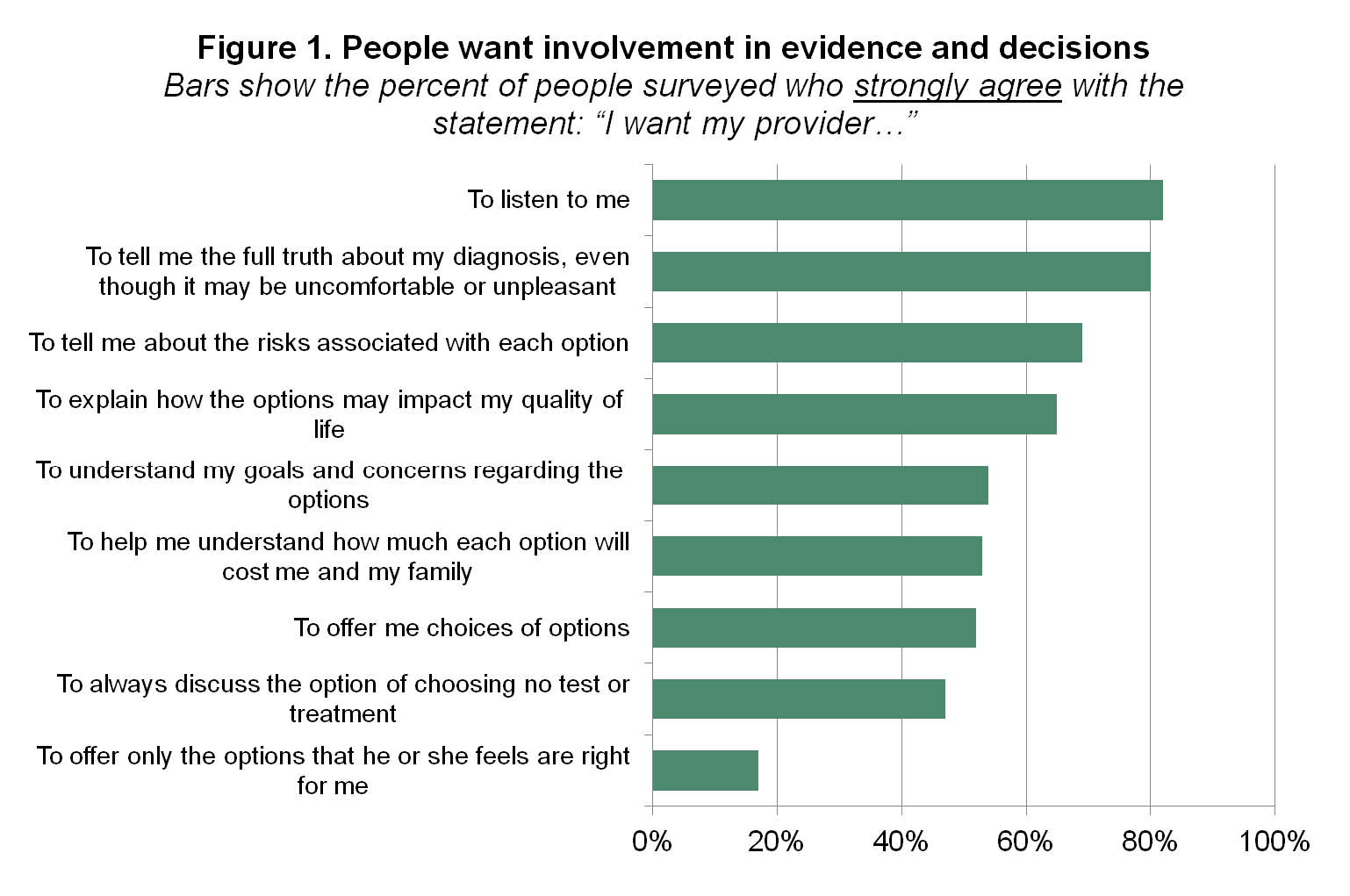

People desire a patient experience that includes deep engagement in shared decision making (Figure 1).

- 8 in 10 people want their provider to listen to them.

- 8 in 10 people want to hear the full truth about their diagnosis.

- 7 in 10 people want to understand the risks of treatments.

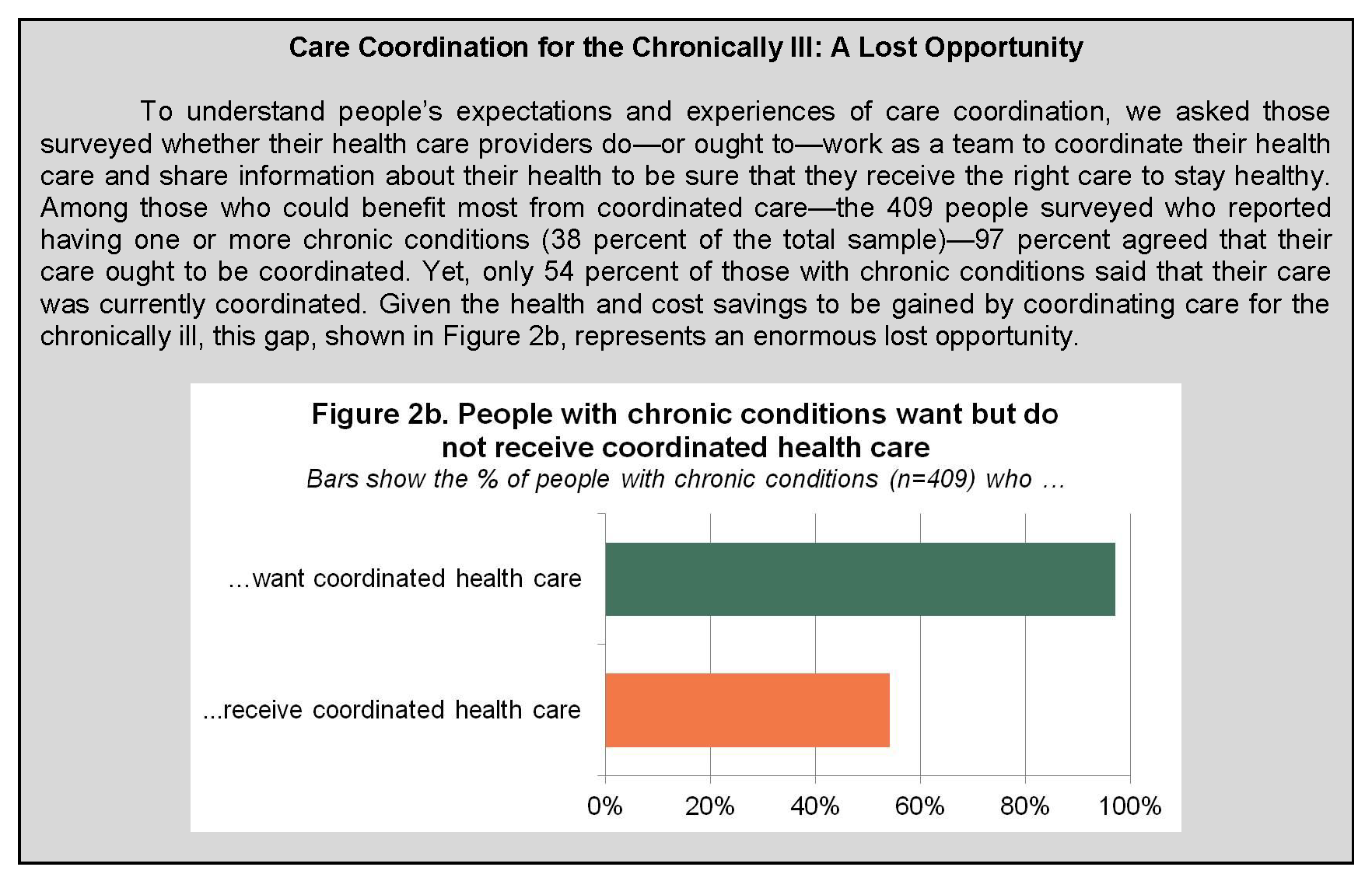

There is a gap between what people want and what they get regarding engagement in health care (Figure 2).

- 8 in 10 people want their health care provider to listen to them, but just 6 in 10 say it actually happens.

- Less than half of people say their provider asks about their goals and concerns for their health and health care.

- 9 in 10 people want their providers to work together as a team, but just 4 in 10 say it actually happens.

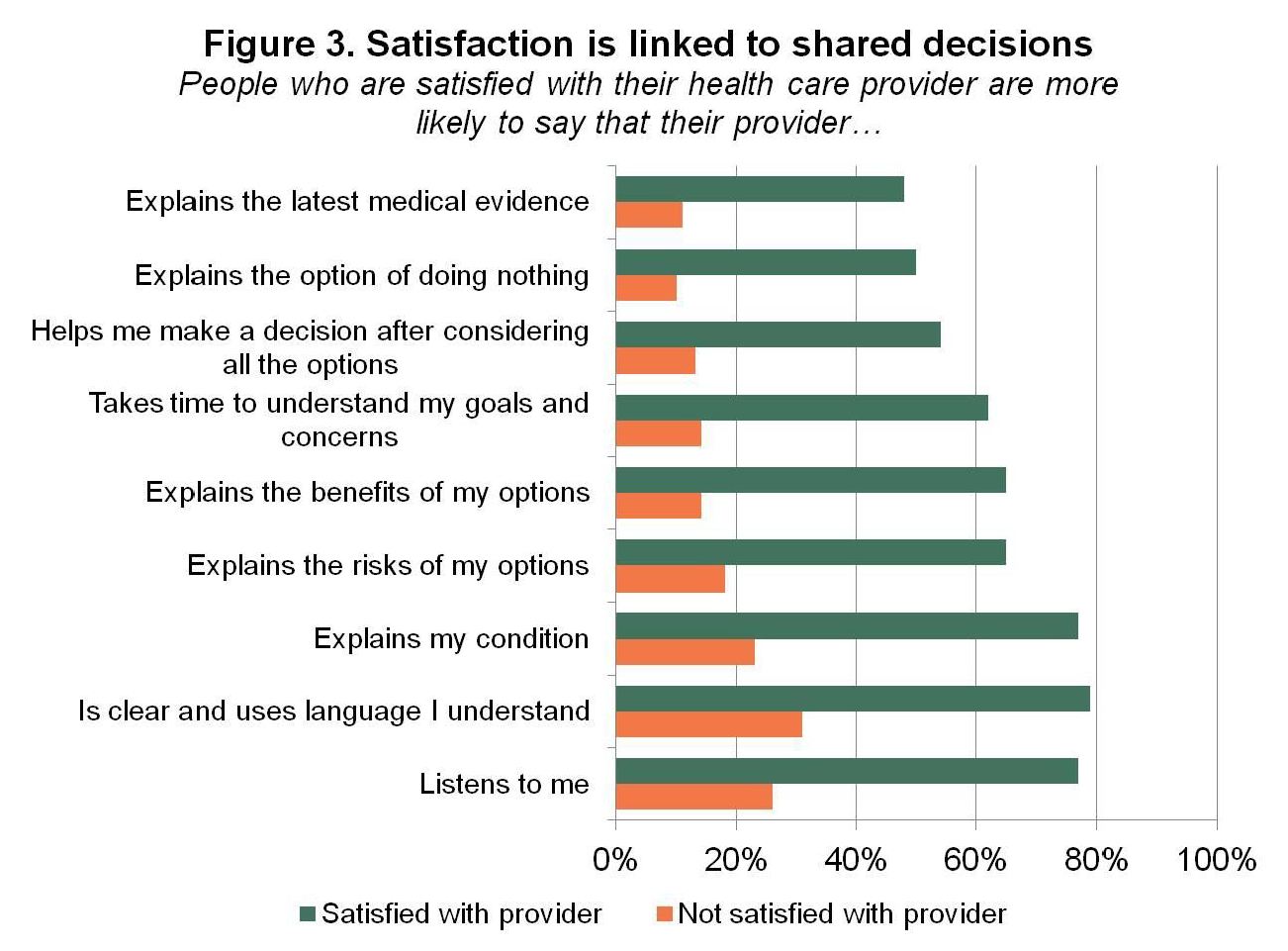

People who are more engaged in health care report a better experience (Figure 3).

- Patients whose providers listen to them, elicit goals and concerns, and explain all the options, among other things, are 3 to 5 times more satisfied with their providers.

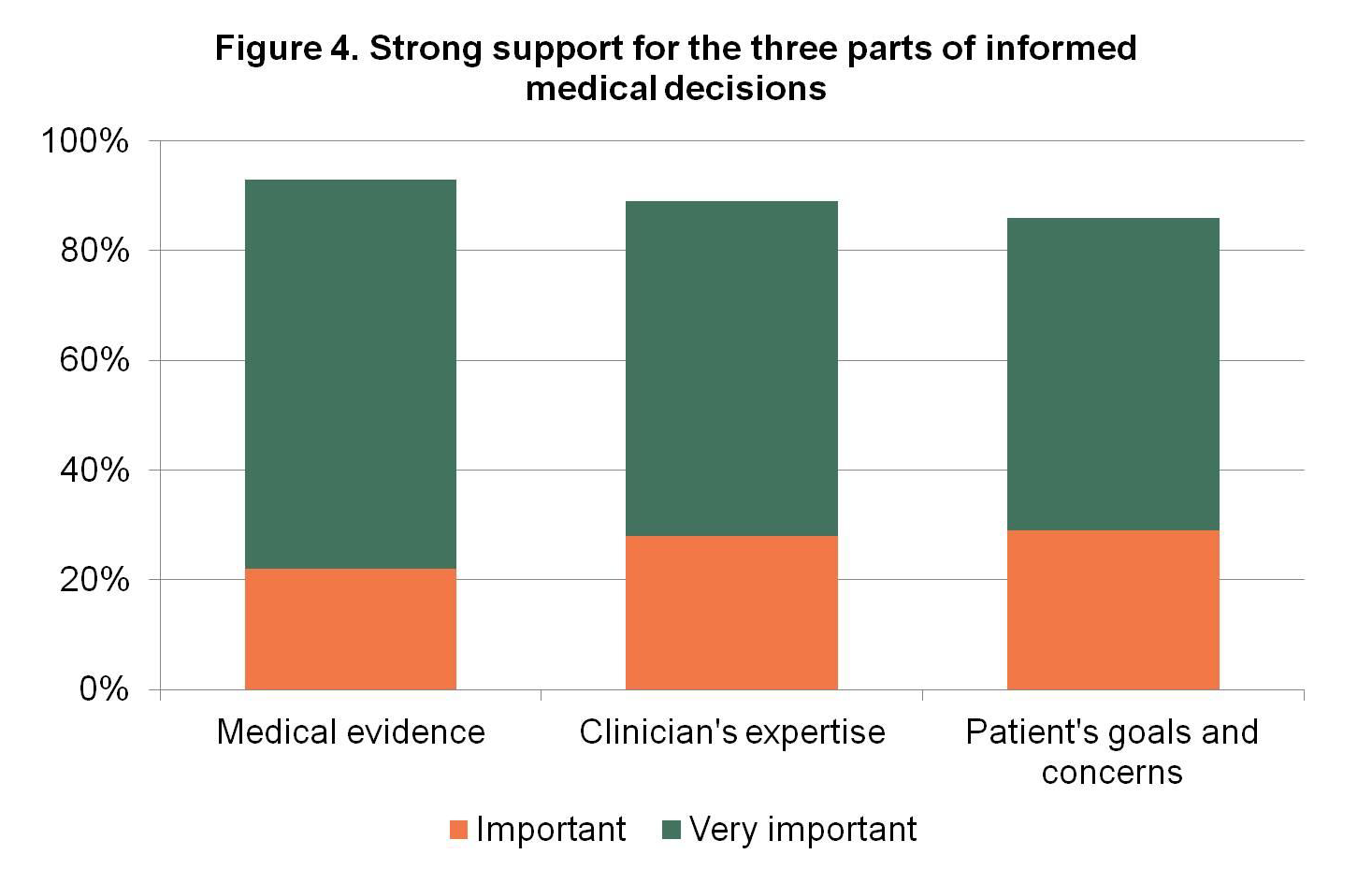

People have clear preferences for evidence communication (Figure 4).

- Medical evidence, the clinician’s expertise, and the patient’s goals and concerns are all critical to making medical decisions.

- To describe medical evidence, people prefer the phrases “what is proven to work best” and “the most up-to-date medical evidence, including information about the risks and benefits.”

9 in 10 people agree that their health data should be used to help improve the care of future patients who might have the same or similar conditions. (See additional explanation on page 11.)

Unfortunately, people often have poor knowledge of key facts about important health decisions they make, and there are important differences between what providers think patients should know and what patients want to know. [6,7,8] Furthermore, implementation of shared decision making is low in the United States. A national survey of adults asked about the experiences of people who considered at least 1 of 9 preference-sensitive medical decisions involving medications, surgery, or screening. The study found that health care providers made a recommendation 8 out of 10 times, and that the clinician recommendation was most often in favor of the intervention—in approximately 90 percent of medication decisions, 65 percent of elective surgery decisions, and 95 percent of cancer screening decisions. Patients also reported that they were not routinely asked about their preferences. Providers’ elicitation of patient preferences was lowest for cancer screening (about 40 percent of the time) and highest for knee- /hip-replacement surgery (80 percent of the time). Health care providers nearly always discussed the “pros” of the intervention (more than 90 percent of the time) but infrequently discussed the “cons” or reasons not to take action, though there was a wide range (20 percent for breast cancer screening versus 80 percent for lower back surgery). [9]

Communicating the importance of medical evidence and a balanced representation of options is the first step toward accelerating patient engagement in shared decision making. Currently, reporting and interpretation of medical evidence are patchy at best and commonly biased, inaccurate, and confusing. At the same time, data show that the public fears that reliance on medical evidence will limit treatment options and jeopardize freedom of choice, limit what insurance will pay for, and lower the quality of care. [10] This paper updates the evaluation of people’s expectations and describes communication strategies and messages that are effective in raising awareness about—and driving demand for—high-quality, shared medical decisions.

Foundational to the discussion in this paper is the first finding (see page 6)—that people want deep and meaningful involvement in medical evidence and decision making. As shown in Figure 1, people want to be listened to and want the full truth from their health care providers, including information about the diagnosis and the risks and impact of treatment options.

Elements of High-Quality Medical Decisions

Achieving high-quality medical decisions requires multiple components. First, people must have timely access to the best available medical evidence. Second, providers must provide sound counsel based upon their clinical expertise and without bias. Lastly, the patient’s and family’s preferences (goals and concerns) must be actively elicited and fully honored. This multi-faceted decision-making process recognizes that, in most cases, there is no “right” decision. [11] The answer to any given medical question is patient-specific; it depends upon the medical evidence, the providers’ clinical expertise, and the unique and individual preferences of the patient and family.

To engage patients as equal partners in shared decision making, a strong effort is needed to improve understanding of the important role of medical evidence. Most patients cannot recall a time when their care provider discussed scientific evidence as the basis for better care, [12] yet, a majority of patients do want to know and talk about the options that are available to them—regardless of whether they ultimately make the final decisions regarding their care. [13] High-quality communication is embedded in the foundation of increasingly popular collaborative care models that promote shared decision making (including the patient-centered medical home, accountable care organizations, and care coordination teams). The concept of evidence in a medical context means different things to different people. For some, the evidence about a treatment, including its risks and benefits, is foundational to making sound medical decisions. For others, it is feared as a harbinger of “cookie-cutter medicine.” Evaluating evidence is the heart of comparative-effectiveness research, which aims to determine what is proven to work best in medicine yet was equated with rationing in the debate over health reform. Public discourse about evidence may generate fear that carries over into medical encounters. Important conversations about medical evidence that include risk and benefit to patients in a meaningful manner cannot happen without effective, evidence-based methods to communicate that evidence.

Approach

The work described in this discussion paper took place over several years in three distinct phases which built upon each other. In the first phase, participants in ECIC worked with RTI International to conduct an environmental scan to understand ongoing efforts to raise awareness about the importance of evidence in medical decision making. The environmental scan led to the development of a framing concept that was refined by ECIC participants. In the second phase, participants sought to understand the applicability of this framing concept to people experienced in medical decision making—those with at least one disease—and to develop a specific message concept and language to improve understanding, appreciation, and discussion among patients and providers on the use of medical evidence to guide clinical choices. To achieve the goals of the second phase, GYMR Public Relations, working in partnership with Lake Research and MSL Washington, conducted individual interviews and focus groups in fall 2011 in three U.S. cities and subsequently developed preliminary messaging for various stakeholders to use when talking about evidence. Finally, in the third phase, participants fielded a nationally representative poll of U.S. adults to quantify the prevalence of the attitudes, beliefs, and preferences uncovered in the qualitative research and compared proposed messaging language. The poll was designed by ECIC participants in conjunction with Consumer Reports, which conducted the survey in March 2012 using the Knowledge Networks online polling service.

Framing the Message: Environmental Scan and Qualitative Research Results

The environmental scan revealed that the focus of most campaigns to raise awareness about and increase demand for medical evidence was general in nature. Examples include the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Questions are the Answer” campaign and the Joint Commission’s “Speak Up” patient-safety initiative. The research revealed the importance of seating more specific campaigns about medical evidence within the context of a clinical encounter that takes into account three vital—and equally important—elements: the expertise of the provider, the medical evidence, and the patient’s preferences (goals and concerns). These three aspects—which we depict as three separate but interlocking circles that, when combined, result in an informed medical decision—were posited to be the best framework for raising awareness about the role and importance of medical evidence for future communication and patient-engagement strategies.

We tested the applicability and acceptability of the three aspects of informed medical decisions during the second phase using individual interviews and focus groups with patients. The GYMR Public Relations report to ECIC presented refined messages designed to raise awareness about medical evidence, to which focus group participants responded positively.14 Key themes that emerged from the interviews and focus groups included that people want to be involved in treatment decisions, want their options to be clearly communicated, and expect the truth—the whole truth—about their diagnoses and treatments. The framing language that resonated best with patients in the interviews and focus groups to explain the importance of medical evidence was

Making sure you get the best possible care starts with you and your doctor making the best decision for you. Your doctor can help you understand what types of care work best for your condition, based on medical evidence. Because there are always new treatments, doctors use this evidence to keep up with which work best. Your doctor’s experience helps him or her evaluate and apply the evidence to your situation. The doctor also needs to listen to you so he or she understands your values, preferences, and goals. This is important because every patient is different, and when there are options, it is important for the doctor to know what is important to you.

The second-best framing language was

When you and your doctor sit down to talk about what tests or treatments to do, the conversation should involve the best medical evidence. But the research is constantly changing as we learn more, so the recommendations may change over time, too. As new treatments are developed, they are compared to the ones that exist today to determine if they’re really better. This is all part of the process of continuously improving our health care choices.

The elements from the framing languages that were key in successful messages include framing messages in a positive way, embedding discussions of medical evidence in the context of a strong relationship with a trusted provider, using language that conveys to patients that the focus is on them, and expressing that the goal is to provide patients with the best possible care. Specific phrases that were particularly effective included

- Making sure you get the best possible care starts with you and your doctor making the best decision for you

- Understand the best types of care based on the most recent medical evidence

- Your doctor needs to listen to you, understand your needs and concerns, and answer your questions

- Every patient is different

Quantifying the Impact: National Survey Results

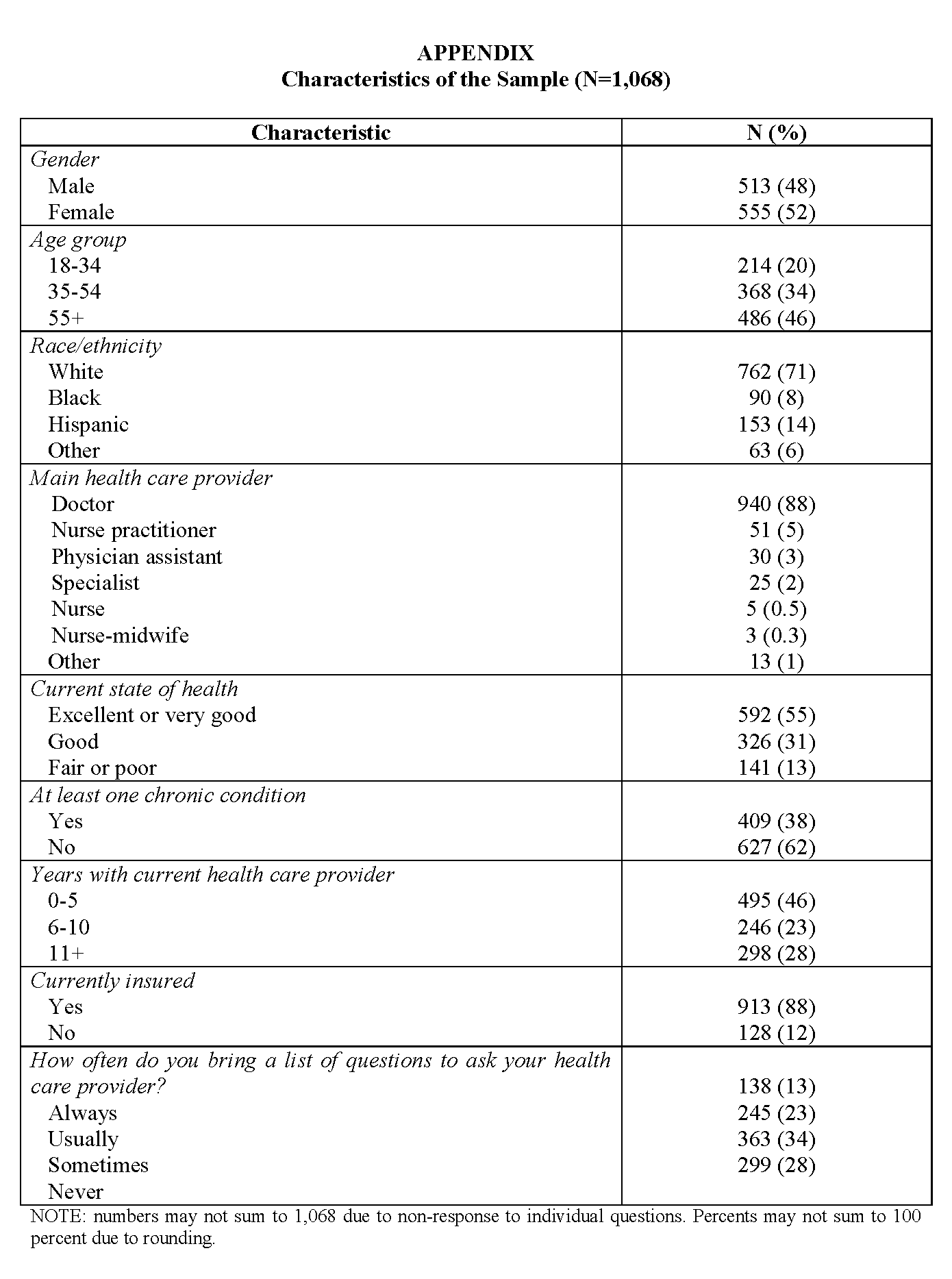

In the third phase of research, we sought to quantify the impact of the three aspects of informed medical decisions, as well as specific message concepts. We surveyed a nationally representative sample of 1,068 U.S. adults who had seen at least one health care provider in the previous 12 months. The majority of those surveyed (88 percent) identified a physician as their main health care provider, and 68 percent indicated that they were satisfied with their main health care provider. A full description of the sample is shown in the Appendix.

With regard to communication of medical evidence, we had five main findings:

- First, we found that people desire a patient experience that includes deep engagement in shared decision making.

- Second, we discovered a gap between patients’ desire for engagement in their own health care and what they say is actually happening in clinics and hospitals across the country with regard to the process of decision making, communication, and the role of patient preferences.

- Third, we found that people want but do not experience coordinated health care designed to promote communication and shared decision making.

- Fourth, we found that people who were more engaged uniformly reported a better experience—specifically, greater satisfaction with their health care provider.

- Finally, we quantified people’s preferences for how to discuss medical evidence.

A Desire for Deep Engagement

We looked at a number of characteristics of patient engagement and found that people desire deep engagement in the process and content of decision making, including respectful communication that acknowledges goals and concerns, detailed discussion of evidence and options, and clear involvement in weighing the options.

Respectful Communication That Acknowledges Goals and Concerns

Respondents clearly view communication as a two-way conversation with their provider, with an emphasis on active listening and adequate time. Those surveyed strongly agreed that they expect their provider to listen to them (82 percent), and would prefer that their provider take the time to understand their goals and concerns (54 percent). Interestingly, in both of these areas there was a significant gender difference, with women indicating stronger preferences than men for listening (87 versus 77 percent [p<0.05]) and elicitation of goals and concerns (60 versus 48 percent [p<0.05]). Importantly, only 59 percent described themselves as “extremely comfortable” with asking questions of their provider, and just 57 percent described themselves as “extremely comfortable” with telling their provider if they don’t understand something. This discomfort indicates that it remains essential for providers and their institutions to shape an environment of open, meaningful communication about medical evidence.

Discussion of Evidence and Options

The vast majority (80 percent) of people strongly agreed that they expect their health care provider to tell them the full truth about their diagnosis, even though it may be uncomfortable or unpleasant to hear at the time. More than two-thirds (69 percent) said they want their provider to tell them the risks of the treatment options so they will know how each might affect them, and 65 percent want to hear about each option’s potential impact on quality of life. More than half (53 percent) wanted to know about each option’s cost to themselves and their family. Almost half (47 percent) of those surveyed said that they want their health care provider to discuss the option of not pursuing a test or treatment, and an additional 41 percent said they “somewhat agreed” with this statement. When it comes to making decisions, though, just one-quarter of patients said that their provider told them where to get more information to help them decide, and only 5 percent said that their provider gave electronic information. Unsurprisingly, 30 percent of people said they “very often” get health information from a source other than their health care provider. The most common sources were their spouse or partner (15 percent), the Internet (9 percent), and a friend or family member who works in health care (6 percent).

Involvement in Weighing the Options

People indicated that although they desire a trusting, respectful relationship with their provider in which the evidence and options are discussed, they do not want their provider to filter the options or make choices for them. The majority of people agreed (52 percent “strongly” and 38 percent “somewhat”) that they want to be offered choices rather than having their provider offer only the option he or she recommends. Only 17 percent of people said that they preferred to know only the options that their provider feels are right for them based on his or her experience. Importantly, the preference for involvement did not vary significantly by gender, age, income, race or ethnicity.

The Gap Between Expected and Actual Engagement in Health Care

We found a distinct disconnect between what patients want in a medical encounter and their actual experiences of communication, discussions of the evidence, and involvement in the decisions during the course of their health care. Sixty-one percent strongly agreed that their provider listens to them. Half strongly agreed that their provider explains the risks of their options. Yet, only 36 percent strongly agreed that their provider clearly explains the latest medical evidence. Less than half (47 percent) said that their provider takes into account their goals and concerns, and only 37 percent said that their provider explains the option of not pursuing a test or treatment. Finally, in an era of increasing complexity and need for good teamwork, less than half said they receive coordinated care. Figure 2 depicts the gap in these five key areas between what people want and what they receive in their health care.

The Link Between Patient Engagement and Satisfaction

In addition to quantifying the gap between the engagement people want and the engagement they get, we found that those who experienced good communication, involvement in decisions, and honoring of their goals and concerns uniformly reported being more satisfied with their care. For example, over three-quarters of those who reported that their provider used clear language and listened were satisfied with their provider, compared with less than a third of those whose provider did not use clear language or listen. Figure 3 displays the relationship between patient engagement and satisfaction in nine patient engagement–related areas. The correlation between engagement and satisfaction underscores the need to measure and provide valuable elements that are both important and meaningful in a patient’s experience.

Interestingly, those surveyed indicated that their health care provider’s in-person communication skills are more important to their satisfaction than access to digital communication vehicles such as email and online access to test results and prescription refills (and more important than even the amount of time providers spend with patients). We want to be clear that we do not believe this finding should be interpreted as a devaluation of the importance of health informatics or the transformative potential of digital technology for health care. Rather, we believe these data indicate that people desire most strongly a trusting, personal relationship with their provider in which all contributions are valued—something they apparently do not often experience.

How to Discuss Medical Evidence

To understand how people feel about the three aspects of informed medical decisions, we asked people to rate the importance of 1) the providers’ clinical expertise, 2) medical evidence, and 3) their own preferences and goals. We found strong support for all three. Figure 4 shows the percentage of people who said that each part was important or very important in their health care. Patients view evidence about what works for their condition as more important than both their provider’s opinion (in second place) and their personal preferences (in third place). The differences were significant but not wide, suggesting the three parts stand well together. There was a significant gender gap on one aspect; more females indicated that their personal goals and concerns are “very important” in the decision-making process (64 percent) than males (50 percent).

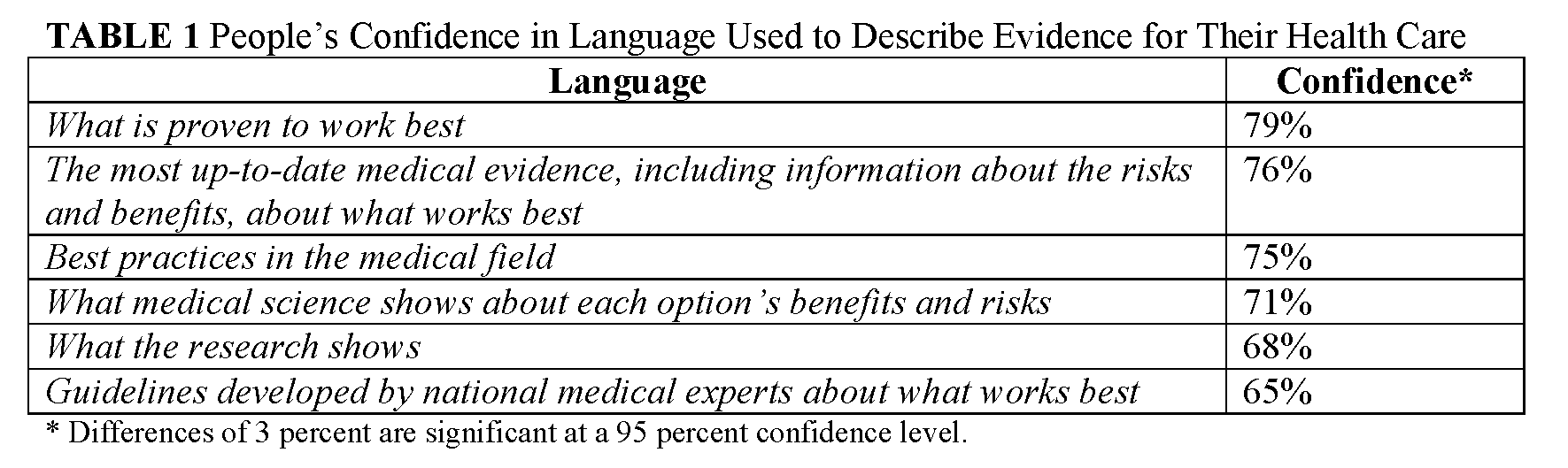

Finally, to determine the specific language that can be used to communicate about medical evidence, we asked people how confident they were that a particular phrase described the information they need to make decisions about treatments with their provider. Table 1 shows the level of confidence in the six statements tested.

Strong Patient Support for Sharing Data to Improve Evidence: More to Come

To explore willingness to share health data to build the evidence database, we asked respondents to say whether they “strongly agree,” “somewhat agree,” “somewhat disagree,” or “strongly disagree” with the statement “My health data should be used to help improve the care of future patients who might have the same or similar condition.” In keeping with patients’ desire to interact meaningfully with information and evidence, 89 percent strongly or somewhat agreed with this statement, and just 3 percent strongly disagreed. This finding indicates that people recognize the common-sense value of sharing information to improve health and health care—and possibly that there is a thirst in the general population for care improvement through data sharing. The fact that the vast majority of respondents agreed with this statement bears further exploration, which will be undertaken by ECIC in the near term.

Conclusions

We conducted research in three stages—environmental scan, qualitative interviews and focus groups, and quantitative survey—to understand Americans’ desire for and experience of engagement in medical evidence and shared decision making. We found that people want deep engagement in conversations about their health care, including detailed medical evidence. They do not want their provider to make decisions for them or offer only some of the options. It is incumbent upon providers and institutions to create the environment and provide the tools to make this possible. Furthermore, we found a gap between what people want and what they get with regard to engagement in health care. Given the health benefits and cost savings demonstrated when patients are actively involved in shared decision making about their health care, this gap represents a lost opportunity to achieve the triple aim—better care, lower costs, and better health.

In addition to wanting involvement in medical decisions, people are aware that there are benefits to care coordination and believe that their care should be better coordinated. People with chronic conditions are even more aware of this need than the general population. Given that the high costs of care for chronic conditions can be lowered through good care coordination—and that people actively want to be involved in better-coordinated care—this gap is both costly and unnecessary.

Patient experience is a focus in the health care arena today. Our data indicate that deep engagement in shared decision making is not only desired by people but is a core component of their experience as patients. Ongoing efforts should focus on the importance of measuring and providing what is important and meaningful to patients. Health care providers and others who seek to engage patients can confidently use the language provided here to describe medical evidence in a way that resonates positively with the general public. People are particularly receptive to conversations about medical evidence in the context of discussions with a trusted, expert health care provider who takes their goals and concerns into account.

Indicated Actions

The goal of this research is to accelerate the routine use of the best available evidence in medical decision making by raising awareness of and increasing demand for medical evidence among patients, providers, health care organizations, and policy makers. Our findings point toward indicated actions to help achieve this goal. We believe there are three key areas of action that can help ensure that every medical decision is an informed medical decision, shared between the health care provider and the patient and family.

Cultural Changes

To achieve the vision of care patients and families desire and deserve, it will be important to recognize and act upon the gap between what they want from their health care system and what they currently receive. Patient awareness of and engagement in the three elements of an informed decision (clinical expertise, medical evidence, and individual goals and concerns) will need to become part of the routine culture of medical decision making. This cultural shift will require that clinicians be encouraged, empowered, and motivated to facilitate informed medical decisions whenever and wherever they practice. The communications literature indicates that encouraging clinicians to adopt the practice of informed medical decision making may be most successful if they are made aware of the benefits to their patients. [15] Within the practice environment, some tools are available to facilitate the integration of balanced presentation of information—including risks, benefits, and “unknowns”—with patients’ goals and concerns, but broader adoption of these tools is needed. The data presented here show clearly the gap between what patients want and what they get and can serve as a stimulus for activation. By coupling knowledge of the broad desire among the public for deeper involvement in health care decision making with information about existing tools—such as mobile technologies, programs in care coordination, and more—patients, families, and other advocates can help drive change with their health care providers and within their health care settings.

Incentive Alignment and Infrastructure Support

With the advent of new payment models focused on managing the health of populations and coordinating care comes a distinct opportunity to advance informed decision making. Patient-centered medical homes, health care exchanges, and accountable care organizations structured to embrace informed medical decision making as a central tenet will enable models of care that deliver on the promise of patient activation and engagement. To support sustainability of these models, public and private payers can provide incentives to clinicians and patients to engage in informed medical decision making.

Several opportunities exist at the institutional level to promote informed medical decisions by making the right thing easy to do. Institutions can help identify high-quality decision aids and make these easily and routinely accessible to clinicians, patients, and families. Institutions can also assist by identifying and making available time, space, and personnel to carry out the process of informed medical decision making. Within the world of health information technology, electronic health records (EHRs) hold the potential to increase patient and family engagement in health care. EHR systems designed to meet “meaningful use” criteria can advance patient and family engagement by including tools designed to promote “meaningful choice.”

A national resource to help facilitate routine use of the best information for medical decisions, including decision aids, is an electronic clinical library that will allow all caregivers and patients to have easy access to medical textbooks, journal articles, and medical protocols. High-quality care sites can feed current best practice tools, protocols, and insights into the electronic library in a context of continuous improvement and shared learning. Such an electronic resource is possible today and should be made available to both clinicians and patients as a foundational tool for continuously improving care and increasing the proportion of medical decisions that are truly informed—and shared—medical decisions.

Quality Standards and Accountability

A widespread system designed to standardize, certify, and disseminate decision aids would help clinicians identify high-quality tools they can trust. Those who educate health professionals can empower clinicians by routinely integrating the concepts, practices, and tools of informed medical decisions into professional education. Accreditation and licensing bodies can further these efforts by building in requirements for skills in informed medical decision making. Legislatures can enact laws that recognize and promote informed medical decision making as superior to standard informed consent for treatment. Quality measures for improvement, performance, and reporting can include the process and outcomes of informed medical decision making.

Conclusion

These three areas of action will be enhanced by a deeper appreciation of how to help people understand the evidence relevant to their well-being and their care and to drive demand for that evidence. Immediate areas for research include understanding the unique perspectives of sub-segments of the American population; delving into the most effective ways of encouraging clinicians to promote informed medical decision making in the routine course of care; and providing incentives for informed medical decision making in practice.

By focusing on these target areas in patient engagement, clinician stewardship, institution and policy facilitation, and research promotion, those dedicated to improving evidence communication can realize a profound and immediate opportunity to improve the health of Americans.

References

- Stacey, D., C. L. Bennett, M. J. Barry, N. F. Col, K. B. Eden, M. Holmes-Rovner, H. Llewellyn-Thomas, A. Lyddiatt, F. Legare, and R. Thomson. 2011. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Systematic Review Oct 5;(10): CD001431. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub3.

- Kennedy, A. D. M., M. J. Schulpher, A. Coulter, N. Dwyer, M. Rees, K. R. Abrams, S. Horsley, D. Cowley, C. Kidson, C. Kirwin, C. Naish, and G. Stirrat.. 2002. Effects of decision aids for menorrhagia on treatment choices, health outcomes, and costs. JAMA 288(21):2701-2708. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.21.2701

- O’Connor, A. M., J. E. Wennberg, F. Legare, H. A. Llewellyn-Thomas, B. W. Moulton, K. R. Sepucha, A. G. Sodano, and J. S. King. 2007. Toward the “tipping point”: Decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Affairs 26(3):716-725. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.716

- O’Connor, A. M., H. A. Llewellyn-Thomas, and A. B. Flood. 2004. Modifying unwarranted variations in health care: Shared decision making using patient decision aids. Health Affairs (Millwood) 63-71. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.var.63

- Schoen, C., S. Guterman, A. Shih, J. Lau, S. Kasimow, A. Gauthier, and K. Davis. 2007. Bending the curve: Options for achieving savings and improving value in U.S. health spending. The Commonwealth Fund Report Volume 80. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2007/dec/bending-curve-options-achieving-savings-and-improving-value-us (accessed February 3, 2020).

- Lee, C. N., C. S. Hultman, and K. Sepucha. 2010. Do patients and providers agree about the most important facts and goals for breast reconstruction? Annals of Plastic Surgery 64(5). https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181c01279.

- Simon, M. A., L. Cofta-Woerpel, V. Randhawa, P. John, G. Makoul, and B. Spring. 2010. Using the word “cancer” in communication about an abnormal pap test: Finding common ground with patient-provider communication. Patient Education and Counseling 81(1):106-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.11.022

- Zikmund-Fisher, B. J., M. P. Couper, E. Singer, P. A. Ubel, S. Ziniel, F. J. Fowler, Jr., C. A. Levin, and A. Fagerlin. 2010. Deficits and variation in patients’ experience with making 9 common medical decisions: The DECISIONS study. Medical Decision Making 30(5):85S-95S. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0272989X10380466 (accessed February 3, 2020).

- Carman, K. L., M. Maurer, J. M. Yegian, P. Dardess, J. McGee, M. Evers, and K. O. Marlo. 2010. Evidence that consumers are skeptical about evidence-based health care. Health Affairs 29(7):1400-1406. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0296.

- Wennberg, D., B. Barbeau, and E. Gerry. 2009. Power to the patient: The importance of shared decisionmaking. Health Dialog. Available at: http://www.bupa.com/media/243488/research_report_-_power_to_the_patient_-_october_2010.pdf (accessed December 21, 2011).

- Carman, K., et al. 2010. Health Affairs 29(7).

- Flynn, K. E., M. A. Smith, and D. Vanness. 2006. A typology of preferences for participation in health care decision-making. Social Science and Medicine 63(5):1158-1169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.030

- GYMR Public Relations. 2011. Developing effective messages for the use of evidence-based medicine. Produced for the Evidence Communication Innovation Collaborative of the Institute of Medicine, October.

- Grant, A. M., and D. A. Hofmann. 2011. It’s not all about me: Motivating hand hygiene among health care professionals by focusing on patients. Psychological Science Dec;22(12):1494-1499. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611419172