Benefit Design to Promote Effective, Efficient, and Affordable Care: A Vital Direction for Health and Health Care

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

This publication is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Vital Directions for Health and Health Care Initiative, which commissioned expert papers on 19 priority focus areas for U.S. health policy by more than 100 leading researchers, scientists, and policy makers from across the United States. The views presented in this publication and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations.

Learn more: nam.edu/VitalDirections

Introduction

As health care spending has risen, employers have tried to alleviate the pressure on premiums and wages by increasing patients’ cost-sharing at the point of service. Since 2010, deductibles have increased by 67% and premiums by 24% compared with only a 10% increase in earnings (Long et al., 2016). Moreover, the Medicare benefit package is incomplete. Most Medicare beneficiaries purchase supplemental coverage, but rising health care premiums and policy changes, such as lower payment to Medicare Advantage plans, may create financial barriers for Medicare beneficiaries. The growth in cost-sharing has led to concerns about an increase in underinsurance (when insured people must pay a large share of their income at the point of service to access care). In 2014, 23% of adults were underinsured compared with 13% in 2005 (Collins et al., 2015).

The projected increase in health care spending and associated increases in premium contributions and cost-sharing create concerns about the ability of households to afford coverage or care. The form of higher spending at the household level also matters. Higher premiums make it harder for people to afford coverage, but benefit design strategies to reduce premiums (such as higher deductibles, coinsurance, and copays) increase risk, causing some unlucky households to face very high out-of-pocket spending.

Publicly financed efforts to mitigate households’ financial burden of premiums and out-of-pocket spending must be weighed against the efficiency losses associated with increased taxes. It is crucial to ask how much health care we can afford to finance with tax revenue, whether directly or through tax exclusions (Glied, 1997). Ultimately, addressing concerns about affordability requires addressing the underlying issue of health care spending growth. Doing that requires some combination of supply-side interventions (such as payment reform) and demand-side interventions (including policies that affect premium contributions or cost-sharing at the point of service).

This chapter discusses the theory and evidence related to demand-side strategies. It focuses on innovative private and public cost-sharing strategies, barriers to progress, and policy options.

Conceptual Issues

Health insurance, which mitigates risk by lowering prices at the point of service, can distort incentives for efficient consumption of care, creating what is commonly known as moral hazard. The inefficiency may take the form of overuse (for example, use of services that receive a D rating from the US Preventive Services Task Force—“there is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits”) or poor shopping (failure to purchase care from low-price, high-quality providers). The lack of effective shopping probably contributes to provider prices well above marginal cost (optimal prices in most economic models are equal to marginal cost) or even inefficient investment in innovation because high prices may direct investment toward excessively priced services. Cost-sharing at the point of service can mitigate those distortions.

However, cost-sharing at the point of service also often induces poor decision making. For example, in a high-deductible health plan, in which there is an incentive to shop, most beneficiaries do not shop well (Brot-Goldberg et al., 2015; Sinaiko et al., 2016). Moreover, the RAND Health Insurance Experiment found that although higher cost-sharing was associated with lower spending, patients reduced use of appropriate and inappropriate services in about the same proportions (Siu et al., 1986). Other evidence suggests that higher cost-sharing reduces use of high-value preventive services for chronic disease (Goldman et al., 2007). To the extent that higher cost-sharing reduces use of high-value preventive or chronic care services, whatever savings result may be fully or partially offset by increased use of services related to disease exacerbations (Chandra et al., 2010; Goldman et al., 2007). High cost-sharing may not have large deleterious effects on health on the average in the general population, but low-income and very sick populations are probably particularly vulnerable.

Higher out-of-pocket costs at the point of service also increase the risk faced by households (Jacobs and Claxton, 2008). With high cost-sharing, households that include sicker members will face higher total costs. Many households, particularly low-income households, may not have the savings available to pay the bills; higher cost-sharing can exacerbate problems with bad debt (Daly, 2013) and even lead to bankruptcy. Pooling risk (through premiums or taxes) can help to reduce spending by those who have expensive chronic conditions or who suffer unexpected expensive health events.

Although this chapter focuses on cost-sharing at the point of service, evidence also suggests that consumers do not make optimal choices among plans. For example, Abaluck and Gruber (2011) suggest that if seniors had made better choices in Medicare Part D, their welfare may have risen by 27%. A recent study showed that when an employer changed plan offerings in such a way that one plan was clearly inferior to one of the others, almost one-third of employees nonetheless enrolled in the inferior plan, many of them for the first time (as active enrollees) (Sinaiko and Hirth, 2011). Similarly, some patients on the exchange may unnecessarily pay higher premiums for gold or platinum when cost-sharing reductions would probably render the lower-premium silver plan just as generous (Sprung, 2015). Thus, although having consumers face the full incremental premium (the amount of the premium above the least expensive alternative) will encourage shopping for lower-premium plans and thus create competition among insurers to provide affordable, high-quality benefit packages, marketplace design must also recognize imperfection in choices.

Despite flaws in decision making (which occur in all markets), reliance on out-of-pocket payments in allocating resources is probably needed to maintain a consumer-centric system. Therefore, it is important to assess the consequences of greater risk and poor decision making and to determine how to improve choice (which will never be perfect).

Even if premiums and cost-sharing are set at the economically efficient level (equal to marginal or incremental cost), they will generate socioeconomic disparities. Willingness to pay, the key determinant of consumer decisions, reflects ability to pay. Free markets lead to income-related disparities in access. Because health care market participants of high and low socioeconomic status are connected through shared-risk pools and provider networks, income-related disparities may have consequences that extend beyond the disadvantaged population.

Existing Opportunities for Progress

Efforts have been under way to develop more sophisticated tools and benefit designs that can replace the traditional blunt cost-sharing structures. Specifically, value-based insurance design (VBID) focuses on encouraging efficient use of services (with less emphasis on the provider or product chosen). Reference pricing and tiered-network products focus on encouraging more efficient choice of provider (with less emphasis on the value of the service).

Value-Based Insurance Design

In traditional benefit packages, out-of-pocket costs do not reflect the expected clinical benefit or value of care. VBID plans attempt to promote efficiency by aligning patients’ out-of-pocket costs with the value of services. Specifically, VBID calls for higher cost-sharing for low-value services and lower cost-sharing for high-value services. VBID plans are designed with “clinical nuance” in mind, in recognition that clinical services differ in associated clinical benefit and that the clinical benefit of a specific service depends on who receives it (and where and when).

Implementation of clinically nuanced cost-sharing has been driven by private payers and was included in Section 2713 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which eliminates patient cost-sharing for primary preventive services (for specified populations) as selected by the US Preventive Services Task Force, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and other agencies.

Early adopters of VBID reduced cost-sharing primarily for medications considered important for controlling chronic conditions. One plan that lowered cost-sharing reduced nonadherence to medication by about 10 percentage points over a year (Chernew et al., 2008). The available evidence suggests that reductions in cost-sharing moderately increase the use of targeted high-value services. However, achieving greater cost savings may require raising copays more aggressively for low-value services. A benefit change in the Mayo Clinic health plan that increased cost-sharing for targeted overused or “preference-sensitive” services—such as diagnostic imaging, outpatient procedures, and laboratory tests—reduced their use (Shah et al., 2011).

Reference Pricing

Health insurance with low cost-sharing and wide provider networks dampens patients’ interest in shopping for lower-priced, high-quality providers and thus reduces providers’ incentive to compete for patients by reducing prices. That dynamic may explain the wide differences (often a factor of 10) in the prices paid for services by private insurers within and among geographic markets (Cooper et al., 2015). Reference pricing (sometimes known as reference-based benefits or reference-based payment) targets that variation in pricing, as distinct from variation in use. A sponsor (employer or insurer) identifies a point along the distribution of prices within the relevant market and limits its payment to that amount, the reference price. The insurer payment limit typically is set at the 60th or 80th percentile in the distribution; this ensures that enough providers charge below the limit. Patients often can compare prices among providers by using online transparency tools. Patients who live in remote geographic areas without access to low-priced providers are often exempted, as are patients whose physicians identify a clinical need to use a high-priced provider or product.

A patient that selects a provider that charges less than or the same amount as the reference amount obtains full insurance coverage. However, a patient that selects a provider that charges more than the reference amount pays the difference. Commonly, the additional payment does not count toward the patient’s deductible or annual out-of-pocket maximum, because it is considered a network exclusion rather than a cost share. For that reason, reference-price payments are not constrained by the limits on annual out-of-pocket payments legislated as part of the ACA.

Research shows strong and consistent consumer responses to reference pricing. In one example, in the 2 years after implementation of the design, consumers increased their use of low-priced providers by 9% for cataract removal, 21% for joint replacement, 14% for arthroscopy, 21% for colonoscopy, and 25% for in vitro laboratory tests compared with matched control groups (Robinson and Brown, 2013; Robinson et al., 2015a,b,c, 2016). No observed effects on quality have been observed.

The savings generated by reference pricing stem mostly from changes in market shares rather than from price reductions by high-priced providers (price competition). One exception is the observed reductions in prices charged for orthopedic surgery by some initially high-priced hospitals that faced reference pricing in the California public employees’ health program, which accounts for a large share of privately insured patients in some geographic markets. In other cases, the share of any one provider’s patients subject to reference pricing has been far too small to induce competitive pricing strategies; this might change if the design is adopted by a larger number of payers.

Tiered and Narrow Networks

Tiered-network plans are plans that place in-network providers into multiple categories (tiers), such as preferred and nonpreferred providers. They require patients to pay more out of pocket if they receive care from nonpreferred providers. They are similar to narrow-network plans, which may not tier in-network providers but drive patients to preferred providers by dropping nonpreferred providers from the network completely.

Tiered- and narrow-network plans are similar to reference-pricing models in that they are designed to encourage patients to seek care from high-value providers, although value often reflects variation in cost more than in quality. However, whereas reference-pricing programs focus on a small number of services, tiered network plans often address all (or nearly all) services of a given type. For example, tiered physician networks generally focus on all physician visits, and tiered hospital networks focus on all admissions (with a few exceptions, such as admissions from the emergency room). Unlike a limited or narrow network, which provides no coverage when an out-of-network provider is used, a tiered network provides coverage at nonpreferred in-network providers subject to higher cost-sharing (but still well below the price of the service).

Evaluations of tiered networks generally find that they influence patient choices, but the evidence is mixed, and effect sizes are modest. For example, one study of incentives to seek care from hospitals that performed well on safety criteria found effects in only one of two groups studied, and then only for medical, not surgical, admissions (Scanlon et al., 2008). Another study of hospital tiering found that the likelihood of admission to the preferred hospitals rose by about 7% and admission to nonpreferred hospitals fell by a comparable percentage (Frank et al., 2015). A study of physician tiering found that it did not cause patients to switch physicians but that new patients were less likely to choose physicians in the lower tier (Sinaiko and Rosenthal, 2014).

Tiered networks raise a number of concerns (beyond the standard concerns related to cost-sharing). They include patient reluctance to switch primary care providers (for tiered physician programs), a patient’s physician’s lack of admitting privileges at a preferred hospital, lack of patient (or referring physician) information about the tiers and thus failure to shop, challenges in measuring quality at a provider-specific level (particularly for individual physicians), and the possibility that tiering will not recognize that quality varies with service. Given those concerns, tiered-network and narrow-network plans are a work in progress. Designers are striving to balance the benefits of better choices (and lower spending) with added risk. Other plan features may enable better versions of the products to be created. For example, if providers in a narrow network work better together, the limitations on choice pose less concern.

Barriers to Progress

There are several barriers to more effective use of cost-sharing.

Quality Measurement

Effective markets require reasonable measures of plan or provider quality. Efforts to measure quality are extensive and continuing, but they are impeded by an inability to get comprehensive data on providers (because data often are controlled by individual payers), by incomplete and imperfect measures, and by challenges in conveying the information to consumers or patients. For example, the Institute of Medicine convened a work group to identify core quality measures with the intent of providing guidance on how to reduce the number of quality measures. Boiling quality measures down to a relatively small set inevitably leaves gaps in measurement, but expanding the set of measures creates administrative burdens and communication challenges.

The details of what is being measured depend on the intent of measurement. Measuring to support patient choice of provider requires provider-specific measurement at a detailed level. For example, a quality measure of cancer care would probably need to reflect cancer type reported at a physician or practice level and adjusted for risk. That creates statistical challenges. Measures and measurement approaches used for payment (in which case aggregation of data on different conditions may be fine) may differ from those used to support clinical improvement. Much of the current attention to quality measurement has not recognized that measurement strategy must reflect intended use and that multiple measurement strategies may therefore be needed. Current quality-measurement efforts often search for a single measure set; too little attention is paid to the intent of measurement or the system of data aggregation and reporting. Existing approaches certainly help patients, but they are a long way from supporting patients’ ability to shop on the basis of price and quality.

Transparency

The effectiveness of the aforementioned benefit-design tools in promoting efficiency and affordability (at least for high-value services and providers) depends on readily accessible and usable information for comparing the cost and quality of health plans, providers, and services. Many services are shoppable, but most patients do not shop (Newman et al., 2016).

To support transparency initiatives, private and public insurers recently have developed and distributed tools to inform consumers about health care quality and cost. For example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) continues to disseminate quality information, and most large insurers and many private firms have created transparency tools to support choices of health plans and providers. There is some encouraging evidence, but it is based on a small number of clinical areas and for the very small number of patients (about 10%) that use the tools (Whaley et al., 2014). Broader evidence suggests a minimal effect of transparency tools on spending, in part because so few patients use them (Desai et al., 2016).

One factor limiting diffusion of transparency tools is the proprietary nature of prices (in the private sector); another is the fact that complex benefit designs result in the dependence of price to the patient on prior claims (for example, whether patients have met their deductible). In fact, CMS lacks enough information on supplemental coverage to support price-transparency efforts tailored to beneficiaries at the point of service. Moreover, cognitive problems (particularly for Medicare beneficiaries), time sensitivity, and the complex and stressful nature of medical care may limit the effectiveness of transparency tools in health care markets, but certainly some shopping is feasible and may improve (Ketcham et al., 2012).

Regulatory Barriers

A number of important regulations limit the ability of sophisticated designs to promote efficiency and affordability. These include nondiscrimination rules, which are vital in ensuring equality and access for all but limit the ability to tie cost-sharing to clinical conditions even though the value of services varies by condition. For example, annual eye examinations are a quality-of-care measure for people who have diabetes mellitus but are not recommended on clinical grounds for those who do not have the condition. Network rules can limit the ability of insurers to create high-value networks and to shop aggressively on behalf of consumers. Consumer and patient protections are vital, but greater targeted flexibility, perhaps for organizations that meet quality benchmarks, could be useful.

Attitudes and Evidence

The benefit designs discussed here are offered by few large self-insured employers. Most employers focus on traditional aspects of benefit design (such as the deductible) to increase consumer cost consciousness. It remains to be seen whether the disadvantages of high deductibles and narrow networks will be widely recognized and lead purchasers to pursue the admittedly more complex alternatives discussed above.

When given a choice, most employers (when selecting insurance on behalf of their employees) and individuals (when choosing within the ACA exchanges) prefer designs that have lower premiums and higher cost-sharing over designs that have higher premiums and lower cost-sharing. That may reflect familiarity with the term premium (in contrast with deductible, for example, which may be poorly understood), shortsightedness on the part of purchasers, misestimation of risk, or other information imperfections. Or it may simply reflect a preference to bear the risks of higher cost-sharing when the alternative is higher premium contributions.

Policy Implications

Cadillac Tax

Under the current tax code, workers commonly do not pay income or Social Security taxes on health-insurance premiums; in contrast, wages are subject to both. That favorable treatment encourages the purchase of more comprehensive insurance, which shields people from the costs of health care at the point of service. The benefit is the largest for high-income workers inasmuch as they face the highest marginal income tax rates. The combined effect makes the current tax treatment both inefficient and inequitable.

The ACA includes a “Cadillac tax,” which limits such favorable tax treatment by placing a 40% excise tax, to be paid by the employer or other sponsor, on high-cost employer-provided insurance. The tax was scheduled to begin in 2018, but the start date has been delayed by 2 years. Many economists would prefer that the Cadillac tax take a different form in which any excess employer contribution would become ordinary taxable income of the employee. The “tax cap,” although disproportionately affecting those in areas that have high health care costs, would make the limit clearer and shift responsibility from employers to employees, who would be encouraged to choose plans that do not exceed the limit. The plans would probably have higher cost-sharing. The concerns associated with imperfections in markets discussed above, as well as equity and affordability concerns associated with higher cost sharing, may be mitigated by more sophisticated benefit design. Moreover, such a tax cap would also be more progressive than the Cadillac tax in that the marginal tax rate rises as income rises.

High-Deductible Health Plans with Health Savings Accounts

High-deductible health plans (HDHPs) coupled with health savings accounts (HSAs) are among the fastest-growing plan types. People who have HSA-eligible HDHPs are required to pay the full cost of most care until deductibles are met. Current regulations permit a “safe harbor” that allows first-dollar coverage of primary preventive services before satisfaction of the deductible. Services meant to treat “an existing illness, injury, or condition” are excluded from pre-deductible coverage in HSA-eligible HDHPs. Evidence shows that consumers who switch to an HDHP reduce use of all services, including potentially valuable care and wasteful services (Brot-Goldberg et al., 2015).

Theoretically, HDHPs could adopt a more flexible benefit design that offers more protection for high-value services through a value-based plan structure. A strategy that explores allowing pre-deductible coverage for some high value, clinically indicated health services on the basis of actuarial value to limit the cost of such additions could produce more effective high-value health-plan designs without fundamentally altering the original intent and spirit of the plans. That could be particularly important for treatments for chronic diseases, which account for 75% of total US health spending.

Clinically nuanced, or “smarter,” deductibles might be a natural evolution of HDHPs in that cost-sharing might be reduced for high-value services and providers and increased for low-value services and providers. That would require greater efforts to measure high-value and low-value services that depend on clinical condition, but as the market for HSA-eligible HDHPs grows, it is important that they avoid creating barriers to access the services that prevent deleterious consequences of chronic disease—services that are among the most important for high-cost patients.

Medicare Benefit Design

The Medicare benefit package has many gaps, including gaps in coverage for long-term care services, dental care, eyeglasses, and hearing aids (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014). Unlike most private insurance plans, Medicare does not have a limit on out-of-pocket costs. Thus, beneficiaries face potentially catastrophic out-of-pocket costs (Cubanski et al., 2014). To avoid such costs, many enroll in supplemental insurance plans that have additional premiums, but these plans, sold separately, increase Medicare spending because Medicare pays a share of the cost of induced use.

One solution would be to restructure the currently fragmented Medicare benefit package (Parts A, B, and D) to provide comprehensive benefits to beneficiaries with lower deductibles and a limit on out-of-pocket costs. Several variants have been proposed, some including Medicare provision of supplemental coverage for an added premium (Aaron and Reischauer, 2015; Davis et al., 2013; Ginsberg and Rivlin, 2015). Because this is premium-financed, it would not have an adverse budgetary effect. Estimates related to one such proposal predict that beneficiaries would spend 17% less than what they are spending if they have traditional Medicare with Part D and a Medigap supplemental plan (Davis et al., 2013).

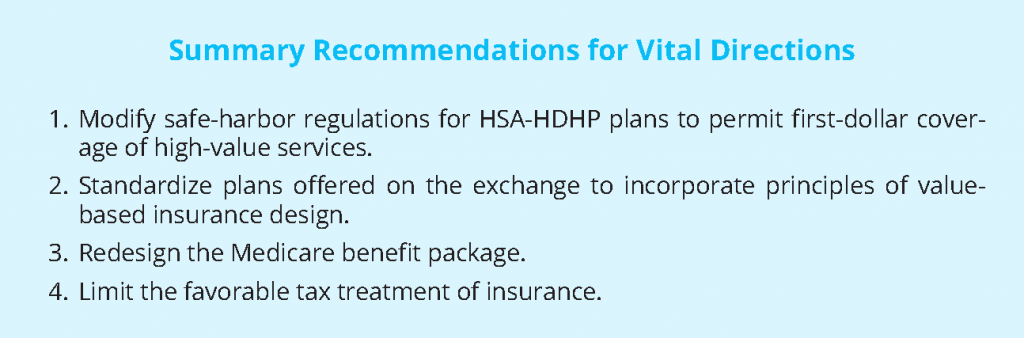

Summary Recommendations for Vital Directions

Rising health care spending has created serious challenges for purchasers in the American health care system. Solutions will require both supply-side and demand-side interventions if they are to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of care to maintain affordability. The different types of strategies are not mutually exclusive but should be harmonized in recognition that neither is perfect. Demand-side strategies, for example, impose risk and may exacerbate socioeconomic disparities. Nevertheless, beneficiary cost-sharing will probably be an important feature of the health care system, and we should strive to ensure that benefit designs do not create barriers to but instead encourage access to high-value services from high-value providers.

In that spirit, we offer four vital directions:

- Modify safe-harbor regulations for HSA-HDHP plans to permit first-dollar coverage of high-value services. Effective management of chronic disease is important for creating value in the health care system. Existing rules force HSA-eligible HDHPs to create financial barriers to chronic disease management, which both discourages takeup of these plans and may lead to deleterious outcomes for enrollees. Redesign of the rules to allow more flexibility in the context of an HDHP could help promote efficient use of care without substantially altering the average plan generosity.

- Standardize plans offered on the exchange to incorporate principles of value-based insurance design. Given the relatively low actuarial values of plans on the exchange, optimizing the designs to support value-based insurance and shopping (without raising actuarial values) could be important. Standardization is important to support plan choice, but the standardized plans should promote value. Covered California has moved in that direction by lowering copays and removing deductibles for primary care services for most enrollees, but more progress could be made.

- Redesign the Medicare benefit package. The Medicare benefit package has many gaps and does not have a limit on out-of-pocket costs. Over time, supplemental coverage may become less generous and more expensive. Redesigning the benefit package to provide comprehensive benefits with lower deductibles and a limit on out-of-pocket costs and with financing by added premiums could help to provide more effective risk protection without a substantial federal budgetary effect. Beneficiaries may pay less because they would not need to buy supplemental coverage.

- Limit the favorable tax treatment of insurance. Favorable tax treatment of insurance is regressive and discourages efficient benefit design. Limiting the tax deductibility of coverage by implementing the Cadillac tax or, preferably, imposing a similar alternative, such as a tax cap, would support efforts to design efficient benefit packages. However, it must be done in a way that uses some of the added revenue to mitigate the adverse consequences, particularly the burden on lower-income taxpayers.

Tradeoffs are inevitable. No policies are perfect. The ultimate test of any health-reform proposal will be whether it improves health and addresses rising costs. Flexibility in benefit design that allows better alignment with value is one leg of the stool and can transform a system driven by incentives to increase volume into a system that encourages better outcomes at an affordable cost.

References

- Aaron, H., and R. Reischauer. 2015. The transformation of Medicare, 2015 to 2030. Forum for Health Economics and Policy 18(2):119-136. Available at: https://econpapers.repec.org/article/bpjfhecpo/v_3a18_3ay_3a2015_3ai_3a2_3ap_3a119-136_3an_3a3.htm (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Abaluck, J., and J. Gruber. 2011. Choice inconsistencies among the elderly: Evidence from plan choice in the Medicare Part D program. American Economic Review 101:1180-1210. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.4.1180

- Brot-Goldberg, Z., A. Chandra, B. Handel, and J. Kolstad. 2015. What Does a Deductible Do? The Impact of Cost-Sharing on Health Care Prices, Quantities, and Spending Dynamics. National Bureau of Economic

Research Working Paper 21632. Available at: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/nbrnberwo/21632.htm (accessed July 28, 2020). - Chandra, A., J. Gruber, and R. McKnight. 2010. Patient cost-sharing and hospitalization offsets in the elderly. American Economic Review 100(1):193-213. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.1.193

- Chernew, M., M. Shah, A. Wegh, S. Rosenberg, I. Juster, A. Rosen, M. Sokol, K. Yu-Isenberg, and A.M. Fendrick. 2008. Impact of decreasing copayments on medication adherence within a disease management environment. Health Affairs 27(1):103-112. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.103

- Collins, S., P. Rasmussen, S. Beutel, and M. Doty. 2015. The problem of underinsurance and how rising deductibles will make it worse. The Commonwealth Fund. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/

publica¬tions/issue-briefs/2015/may/problem-ofunderin¬surance (accessed June 7, 2016). - Cooper, Z., S. Craig, M. Gaynor, and J. Van Reenen. 2015. The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 21815. Available at: https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/21815.html (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Cubanski, J., C. Swoope, A. Damico, and T. Neuman. 2014. How much is enough? Out-of-pocket spending among Medicare beneficiaries: A chartbook. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: http://kff.

org/medicare/report/how-much-is-enough-out-of-pocket-spending-among-medicare-beneficiaries-achartbook/ (accessed June 15, 2016). - Daly, R. 2013. Shifting burdens: Hospitals increasingly concerned over effects of cost-sharing provisions in health plans to be offered through insurance exchanges. Modern Healthcare. Available at: http://www. modernhealthcare.com/article/20130615/MAGAZINE/306159953 (accessed May 25, 2016).

- Davis, K., C. Schoen, and S. Guterman. 2013. Medicare essential: An option to promote better care and curb spending growth. The Commonwealth Fund. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/

files/publications/in-the-literature/2013/may/1689_davis_medicare_essential_ha_05_2013_itl.pdf (accessed May 29, 2016). - Desai, S., L. Hatfield, A. Hicks, M. Chernew, and A. Mehrotra. 2016. Association between availability of a price transparency tool and outpatient spending. JAMA 315(17):1874-1881. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.4288

- Frank, M. B., J. Hsu, M. B. Landrum, and M. E. Chernew. 2015. The impact of a tiered network on hospital choice. Health Services Research 50(5):1628-1648. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12291

- Ginsberg, P., and A. Rivlin. 2015. Challenges for Medicare at 50. New England Journal of Medicine 373:1993-1995. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1511272

- Glied, S. 1997. Chronic condition: Why health reform fails. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Available at: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674128934 (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Goldman, D., G. Joyce, and Y. Zheng. 2007. Prescription drug cost sharing: Associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA 298(1):61-69. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.1.61

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2014. Medicare at a Glance. Available at: http://kff.org/medicare/factsheet/medicare-at-a-glance-fact-sheet/ (accessed June 18, 2016).

- Jacobs, P., and G. Claxton. 2008. Comparing the assets of uninsured households to cost-sharing under high-deductible health plans. Health Affairs 27(3). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.w214

- Ketcham, J., C. Lucarelli, E. Miravete, and M. C. Roe¬buck. 2012. Sinking, swimming, or learning to swim in Medicare Part D. American Economic Review 102(6):2639-2673. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.6.2639

- Long, M., M. Rae, G. Claxton, A. Jankiewicz, and D. Rousseau. 2016. Recent trends in employer-sponsored health insurance premiums. JAMA 315(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.17349

- Newman, D., S. Parente, E. Barrette, and K. Kennedy. 2016. Prices for Common Medical Services Vary Substantially Among the Commercially Insured. Health Affairs 35(5):923-927. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1379

- Robinson, J., and T. Brown. 2013. Increases in consumer cost-sharing redirect patient volume and reduce hospital prices for orthopedic surgery. Health Affairs 32(8):1392-1397. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0188

- Robinson, J., T. Brown, and C. Whaley. 2015a. Reference-based benefit design changes consumers’ choices and employers’ payments for ambulatory surgery. Health Affairs 34(3):415-422. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1198

- Robinson, J., T. Brown, C. Whaley, and K. Bozic. 2015b. Consumer choice between hospital-based and free-standing facilities for arthroscopy. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 97:1473-1481. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.O.00240

- Robinson, J., T. Brown, C. Whaley, and E. Finlayson. 2015c. Association of reference payment for colonoscopy with consumer choices, insurer spending, and procedural complications. JAMA Internal Medicine 175(11):1783-1791. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4588

- Robinson, J., C. Whaley, and T. Brown. 2016. Association of Reference Pricing for Diagnostic Laboratory Testing with Changes in Patient Choices, Prices, and Total Spending for Diagnostic Tests. JAMA Internal Medicine 176(9):1353-1359. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2492

- Scanlon, D., R. Lindrooth, and J. Christianson. 2008. Steering patients to safer hospitals? The effect of a tiered hospital network on hospital admissions. Health Services Research 43(5):1849-1868. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00889.x

- Shah, N., J. Naessens, D. Wood, R. Stroebel, W. Litchy, A. Wagie, J. Fan, and R. Nesse. 2011. Mayo Clinic employees responded to new requirements for cost-sharing by reducing possibly unneeded health services use. Health Affairs 30(11):2134-2141. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0348 (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Sinaiko, A., and R. Hirth. 2011. Consumers, health insurance, and dominated choices. Journal of Health Economics 30(2):450-457. Available at: https://econpapers.repec.org/article/eeejhecon/v_3a30_3ay_3a2011_3ai_3a2_3ap_3a450-457.htm (accessed July 28, 2020).

- Sinaiko, A., and M. Rosenthal. 2014. The impact of tiered physician networks on patient choices. Health Services Research 49(4):1348-1363. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12165

- Sinaiko, A., A. Mehrotra, and N. Sood. 2016. Cost-sharing obligations, high-deductible health plan growth, and shopping for health care: Enrollees with skin in the game. JAMA Internal Medicine 176(3):395-397. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7554

- Siu, A., F. Sonnenberg, W. Manning, G. Goldberg, E. Bloomfield, J. Newhouse, and R. Brook. 1986. Inappropriate use of hospitals in a randomized trial of health insurance plans. New England Journal of Medicine 315:1259-1266. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198611133152005

- Sprung, A. 2015. When Silver is worth more than Gold or Platinum: Media coverage of high out-of-pocket costs neglects to note that ACA’s Silver plans are often worth more than their weight in gold. Available at:

https://www.healthinsurance.org/ blog/2015/06/12/when-silver-is-worth-more-than-gold-or-platinum/ (accessed August 1, 2016). - Whaley, C., J. Chafen, S. Pinkard, G. Kellerman, D. Bravata, R. Kocher, and N. Sood. 2014. Association between availability of health service prices and payments for these services. JAMA 312(16):1670-1676. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.13373