Beyond Survival: The Case for Investing in Young Children Globally

Executive Summary

Investing in young children (The UN defines the early childhood period as beginning prenatally through age 8) globally is a primary means of achieving sustainable human, social, and economic development, all of which are vital to ensuring international peace and security. Strategic investments in children have been recognized by the world’s leaders in their recent adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals, which aim to further peace, end global poverty, and ensure that all human beings can fulfill their potential in dignity (United Nations, 2015). For the first time, early childhood development is acknowledged as a critical part of the global development agenda. Although child development is explicitly referenced under the new education goal, it is naturally linked to other goals—reducing poverty, improving health and nutrition, promoting equality for girls and women, and reducing violence (United Nations, 2015). Indeed, coordinated, evidence-based investments must be made across sectors to ensure that more and more children not only survive but also thrive.

This paper is a call to action, informed by science from multiple disciplines. We hope it will help to close the gap between what is known and what is done to support the development of children globally and, in turn, sustainable progress for communities and nations.

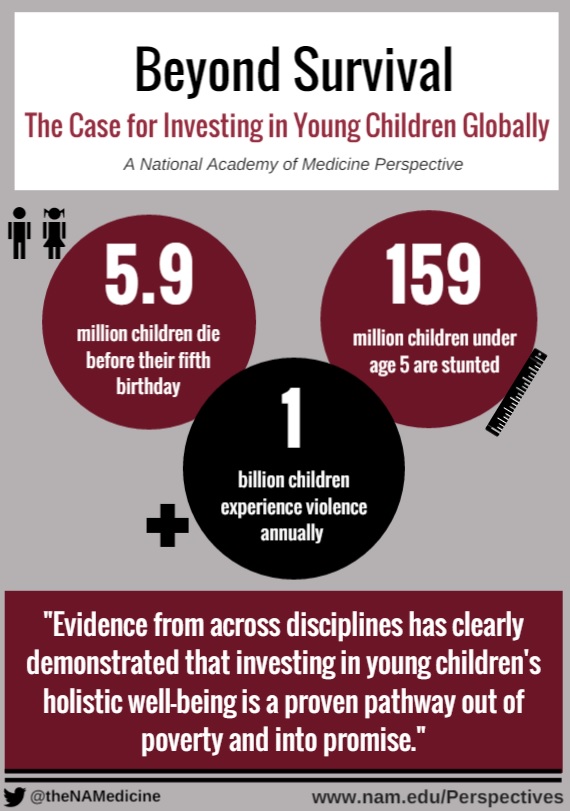

The cost of inaction is enormous (IOM/NRC, 2014). Currently, an estimated 5.9 million children die before their fifth birthday (UNICEF, 2016); 159 million children under age 5 are stunted (UNICEF, 2015); at least 200 million children fail to reach their developmental potential each year (Grantham-McGregor et al., 2007); and 1 billion children experience violence annually (Hillis et al., 2016). As a result, countries lose up to about 30 percent in adult productivity every year (Grantham-McGregor et al., 2007). Meanwhile, return on investments during the prenatal and early childhood years average between 7 and 10 percent greater than investments made at older ages (Carneiro and Heckman, 2003). Although there are other opportunities to enhance human development, cost-effective strategic investments made during children’s early years can mitigate the deleterious effects of poverty, social inequality, and discrimination, ultimately resulting in long-lasting gains that reap benefits for children and youth, families, communities, and nations (Carneiro and Heckman, 2003).

Over the course of the last two decades, this knowledge has begun to infiltrate U.S. domestic policy and programs (IOM, 2000). Yet, investing in young children’s developmental potential has been a more difficult proposition to sell in some U.S. foreign assistance policy and program circles. The science is clear—and globally applicable—and successful programs have been piloted and brought to scale, both within the United States and internationally. Early investment in young children’s development appears to trigger a multiplier effect, with positive outcomes ricocheting across multiple sectors over the long term. Nevertheless, the compelling case for investment continues to be lost in translation.

The U.S. government spends more than $30 billion on foreign assistance (According to ForeignAssistance.gov, $33.9 billion is planned in foreign aid in fiscal year 2017. The website offers a breakdown of expenditures by sector and country) and has been at the front line of cutting-edge investments in development for decades. Still, many policies and programs—not to mention the funding to support them—have not kept up with the science that underscores the critical importance of investing early and holistically to ensure healthy and productive lives and communities.

Currently, U.S. government foreign assistance remains fragmented, with little focus on or cross-sectoral funding for holistic child development and with limited mechanisms in place to ensure effective coordination across sectors. Without a proactive effort to integrate programs for young children, harmonize implementation, and synchronize the measurement of results, program and outcome siloes are created, and an important opportunity to maximize results for children is lost. Young children’s needs and risks are multidimensional. Tackling one issue at a time, divorced from a more complex reality, is ultimately a disservice to time- and resource-strapped vulnerable families. Young children require integrated support, including health, nutrition, education, care, and protection. The science explains why. By turning attention and resources toward coordinated investments and delivery platforms, it is possible to close the gap between what is known and what is done to support young children globally.

Beyond Survival: Expanding the Vision

Evidence-based, results-oriented, coordinated, and effectively monitored international development assistance works. The success of the “child survival revolution” is an important example. In the past two decades alone, child deaths have fallen dramatically, from 12 million in 1990 to 5.9 million in 2015 (UNICEF, 2016). This significant progress is largely due to strategic investments, high-impact interventions, and tools for child survival, notably new vaccines and improved health care practices. Shared targets and coordinated interventions on the part of global public and private partners have ensured that the momentum is maintained.

The success of the child survival revolution is inextricably linked to the focused attention and dedicated funding it has rightfully received for decades from the global development community and donors, including the U.S. government. In 2014, total global development assistance for maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) was approximately $9.6 billion, around $1 billion less than the amount provided for HIV/AIDS. Of this total, $3.0 billion was allocated to maternal health. The other $6.6 billion focused on child health activities. Since 1990, the U.S. government has consistently served as the largest source of development assistance for global health. Across MNCH sources, the United States was the origin of 20.8 percent of all MNCH funding in 2014, 72.1 percent of which was channeled through U.S. bilateral aid agencies. Other channels in receipt of substantial U.S. government support for MNCH were UN agencies (8.8 percent, or $177 million), nongovernmental organizations and foundations (7.4 percent, or $148 million), and Gavi, the vaccine alliance (8.9 percent, or $179 million) (IHME, 2014).

Despite this sustained investment and hard-earned progress in reducing preventable childhood deaths, approximately 200 million children under age 5 survive, but fail to thrive. This figure represents 30 times the number of children who die before they reach their fifth birthday and is a population requiring urgent attention (GranthamMcGregor, 2007). Spending early childhood in the midst of extreme poverty and experiencing significant deprivation, violence, and/or neglect results in devastating consequences throughout the life cycle and profound repercussions for society. These 200 million children live below the poverty line and/or are stunted. They attend school for fewer years—or not at all. They are disproportionately affected by violence and are more likely to be exploited. All these factors limit their future ability to live healthy and productive lives, obtain gainful employment, and contribute to their communities and families, perpetuating a multigenerational cycle of poverty. As a result, countries where these 200 million children live have an estimated 30 percent loss in adult productivity and are prone to instability and conflict (Grantham-McGregor, 2007).

If we are serious about eradicating poverty and fostering equity, we must aim higher. Ensuring survival is a crucial first step, of course, but this should be our minimum standard for success. The campaign to save lives will be incomplete if the future prospects of those who survive remain constrained by factors that, with the right attention and focus, could be effectively addressed (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Indeed, improving outcomes for those who survive the scourge of childhood deprivation and illness should be seen as a compelling priority from the standpoint of human rights, sustainable economic and social development, and global security.

The fact is, children develop holistically. As whole human beings, we do not first survive physically and then develop intellectually, socially, and emotionally. The processes of growth and development are by nature interrelated, interdependent, and mutually reinforcing. Yet, international assistance for children in developing countries is rarely holistic. As a foreign assistance community committed to achieving sustainable human, social, and economic development and international security, we have separated children according to the category of their vulnerability and intervened in line with sectoral predispositions, legislative mandates, and associated funding streams. Yet, this segregated, fragmented approach to sustainable development does not offer the greatest return on investment.

Established and emerging science continues to demonstrate that to promote “child thrival” successfully, investments and services must be coordinated and integrated where possible, concurrently addressing the health, nutrition, development, education, and protection needs of children, beginning prenatally and, better yet, during the preconception period. (For instance, the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child is a multidisciplinary, multi-university collaboration committed to closing the gap between what we know and what we do to promote successful learning, adaptive behavior, and sound physical and mental health for all young children. Established in 2003, the council translates science to build public will that transcends political partisanship and recognizes the complementary responsibilities of family, community, workplace, and government to promote child well-being. See http://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/national-scientific-council-on-the-developing-child/. The Forum on Investing in Young Children Globally was launched in 2014. The forum is a 3-year effort that aims to integrate knowledge with action in regions around the world to inform evidence-based, strategic investments in young children. See http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/activities/children/investingyoungchildrenglobally.aspx.) This knowledge can inform innovative strategies to address child survival and well-being across domains, leading to improved outcomes for children over the long term as they venture into adulthood in ways that did not exist even 10 years ago (Shonkoff et al., 2012). Focusing on integrated investments and interventions for children ages 0-8 aims to create a multiplier effect, building a solid foundation to support long-term development and scaffolding for opportunities across domains.

Child survival can no longer be a sufficient goal. A moral and economic imperative exists to build on the successes of the last two decades and achieve a future for the world’s children that envisions healthy and productive lives beyond survival.

From Neurons to Nations: Building the Architecture for the Future

Frederick Douglass, an African American social reformer and statesman is said to have written, “It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.” This statement not only sounds good; it is biologically true and sensible from an economic perspective as well.

Major advances in neuroscience, molecular biology, genomics, psychology, sociology, and other fields have helped us to understand the significance of early experiences on lifelong health and development. To analyze what science tells us about this critical period, the National Academies’ Board on Children, Youth, and Families (See http://sites.nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/BCYF/index.htm.) established the Committee on Integrating the Science of Early Childhood Development in 1997. The committee was charged with reviewing what is known about the nature of early development and the role of early experiences and to discuss the implications of this knowledge base for policy, practice, and further research.

From Neurons to Neighborhoods is the product of this two-and-a-half-year project during which a top-tier scientific committee analyzed and evaluated the extensive, multidisciplinary, and complex science of early human development (IOM, 2000). The committee examined how early experiences affect all aspects of development, from the neural circuitry of the growing brain, to the expanding network of a young person’s social relationships, to the enduring and changing values of the society in which caregivers raise children. The committee addressed the critical need to use knowledge about early childhood to maximize the nation’s human capital and to nurture, protect, and ensure the health and holistic well-being of all children.

The committee’s work was the beginning of a sustained and concerted effort to bridge the gap between what is known and what is done to promote sound physical and mental health and successful learning for all young children in the United States. Following the impactful From Neurons to Neighborhoods consensus study, the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child was formed to generate, analyze, and integrate scientific knowledge to educate policy makers, civic leaders, and the general public about the rapidly growing science of early childhood development and its underlying neurobiology.

Part of this effort has centered on building awareness on how early experiences affect the development of brain architecture, which provides the foundation for all future learning, behavior, and health. “Just as a weak foundation compromises the quality and strength of a house, adverse experiences early in life can impair brain architecture, with negative effects lasting into adulthood” (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2007). Neural connections are made at a significant speed in a child’s early years, and the quality of these connections is affected by the child’s environment, including nutrition, interaction with caregivers (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2004), and exposure to adversity, or toxic stress (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2005/2014).

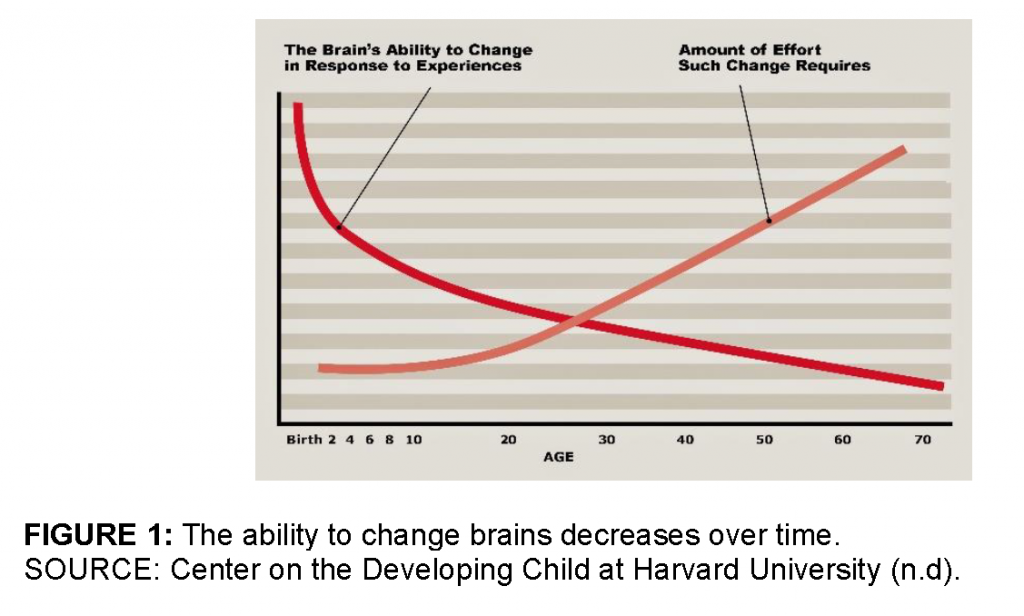

As one commentator put it simply: “Childhood is not Las Vegas. What happens in childhood does not stay in childhood” (Eloundou-Enyegue, 2014). The experiences children have in their early lives—and the environments in which they have them—exert a lifelong impact. These experiences shape the developing brain architecture and influence how and what genes are expressed over time. This dynamic process affects whether children grow up to be healthy, productive members of society (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2010b). This is not to suggest that compromised beginnings cannot be turned around. Indeed, children’s resilience is a powerful reality, achieved when protective factors—particularly a stable and committed relationship with a supportive parent, caregiver, or other adult—outweigh other risks (Masten, 2014; Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2015). The neurobiology of brain development clearly shows that it is easier, more efficient, and more cost-effective to build strong beginnings than it is to facilitate repairs later in life, when brain architecture is less malleable (see Figure 1).

In addition to the important advances made in better understanding the neurobiological elements of early childhood, James J. Heckman, a Nobel Laureate in Economics, has shown that rates of return on investments made during the prenatal and early childhood years average between 7 and 10 percent greater than investments made at older ages (see Figure 2) (Carneiro and Heckman, 2003; Heckman, 2008). Heckman’s cutting-edge work with a consortium of economists, psychologists, statisticians, and neuroscientists shows that early childhood development directly influences economic, health, and social outcomes for individuals and society. His work has demonstrated how adverse early environments create deficits in skills and abilities that drive down productivity and increase social costs—thereby adding to financial deficits borne by the public (Heckman, undated).

As a result of this growing knowledge, over the past two decades we have seen a nationwide groundswell of interest in the critical early years. “In many ways, the 1990s represented an awakening of federal action on child care and early childhood issues that had been slow to evolve in the earlier decades. Emerging evidence and important state and legislative action laid the groundwork for many of the policy issues and debates we see today” (Lombardi et al., 2016). There is now widespread recognition in the United States that what happens during the early childhood period can either contribute to children’s healthy development or set the stage for problems in school and throughout life, taking a long-term economic toll on individuals, families, communities, and even the nation. Bipartisan legislation supporting early childhood policies and programs has been passed in dozens of states, and nearly every state has some kind of early childhood agenda (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2014). Following on progress made under previous administrations (Lombardi et al., 2016), President Obama noted the science of early childhood in several of his State of the Union addresses, making a clear connection between strategic investments in young people and the progress of our nation (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2014). The president’s budget for fiscal year 2017 prioritizes early investments in children, including $1.2 billion to expand early intervention and preschool programs, $9.6 billion for Head Start, and $15 billion in new funding over the next 10 years to extend and expand evidence-based, voluntary home visiting programs, which enable nurses, social workers, and other professionals to support new and expectant parents (U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2016).

Unfortunately, these connections have not been emphasized or prioritized in U.S. foreign policy or assistance programs (U.S. Department of State, 2015; U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2016). (The Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review provides a blueprint for advancing America’s interests in global security, inclusive economic growth, climate change, accountable governance, and freedom for all. As a joint effort of the Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development, the review identifies major global and operational trends that constitute threats or opportunities and delineates priorities and reforms to ensure our civilian institutions are in the strongest position to shape and respond to a rapidly changing world.) Nevertheless, the science that has informed U.S. domestic policies and programs is now being examined at a global level. Of note, the National Academy of Sciences—established by an Act of Congress in 1863 and charged with providing independent, objective advice to the nation on matters related to science and technology—established a Forum on Investing in Young Children Globally in 2014. (See http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/activities/children/investingyoungchildrenglobally.aspx) The forum, a collaboration between the Board on Global Health and the Board on Children, Youth, and Families, aims to integrate knowledge with action in regions around the world to inform evidence-based, strategic investments in young children. Its main objectives are to explore global integrated science of healthy child development through age 8; share models of program implementation at scale and financing across social protection, education, health, and nutrition in various country settings; promote global dialogue on investing in young children; and catalyze opportunities for intersectoral coordination at local, national, and global levels. Just as the National Academy of Science’s From Neurons to Neighborhoods considered the connection between investments in young children and the ability of American children, families, and communities to prosper, the organization is now dedicated to ensuring that decision-makers around the world use the best science and evidence for investing to optimize the well-being of children and their lifelong potential—from neurons to nations, (Jack Shonkoff (Harvard Graduate School of Education; Harvard Medical School; Harvard School of Public Health), Charles A. Nelson (Harvard School of Public Health), and Holly Schindler (Harvard Graduate School of Education) taught an undergraduate course titled “From Neurons to Nations: The Science of Early Childhood Development and the Foundations of a Successful Society.” See http://isites.harvard.edu/course/colgsas-81179.) so to speak.

The convergence of the biological, developmental, and economic sciences continues to remind us that the clock is always ticking and the cost of inaction continues to rise as time passes (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2014). Despite the fundamental principles of biology and human development—or, human capital formation (Heckman, 2007)—the critical importance of timely and integrated early intervention is often overlooked in our international development and child policies and programs. It is time that our programs, policies, and investments more closely correspond with the established science. It is the best and most cost-effective means to ensure that children, families, communities, and nations catch up with their developmental potential.

Recognizing the Multidimensionality of Children’s Well-Being

Investments in child health and well-being are a cornerstone for productive adulthood and robust communities and societies. Promoting healthy and holistic child development is an investment in a country’s future workforce and ability to thrive economically. Ensuring that all children, including the most vulnerable living at the margins of society, have the best first chance in life is a tried-and-true means to stabilize individuals, communities, and societies over the long term.

Risk factors affecting healthy child development are complex and manifold, including undernutrition, toxic stress, and lack of access to life-saving vaccines, nurturing care, protection, and opportunities to learn (Evans et al., 2013; Wachs and Rahman, 2013). U.S. international assistance programs have typically focused on single risks or categories of vulnerability—for example, responding to the devastating impacts of HIV/AIDS or malaria, natural disasters or human conflict, exposure to violence, exploitation, or human rights violations such as child marriage. These diverse efforts to support and protect children have produced substantial benefits, though the diffused approach has also resulted in fragmented responses. Siloed interventions lead to siloed outcomes. By focusing on only a single element of the burden of risks, the effect on outcomes is diminished (Singer, 2014). Science has shown that coordinated, multifaceted, and evidence-based action can help ensure that children in adversity benefit fully from policies and services and achieve better outcomes over the long term (Boothby et al., 2012).

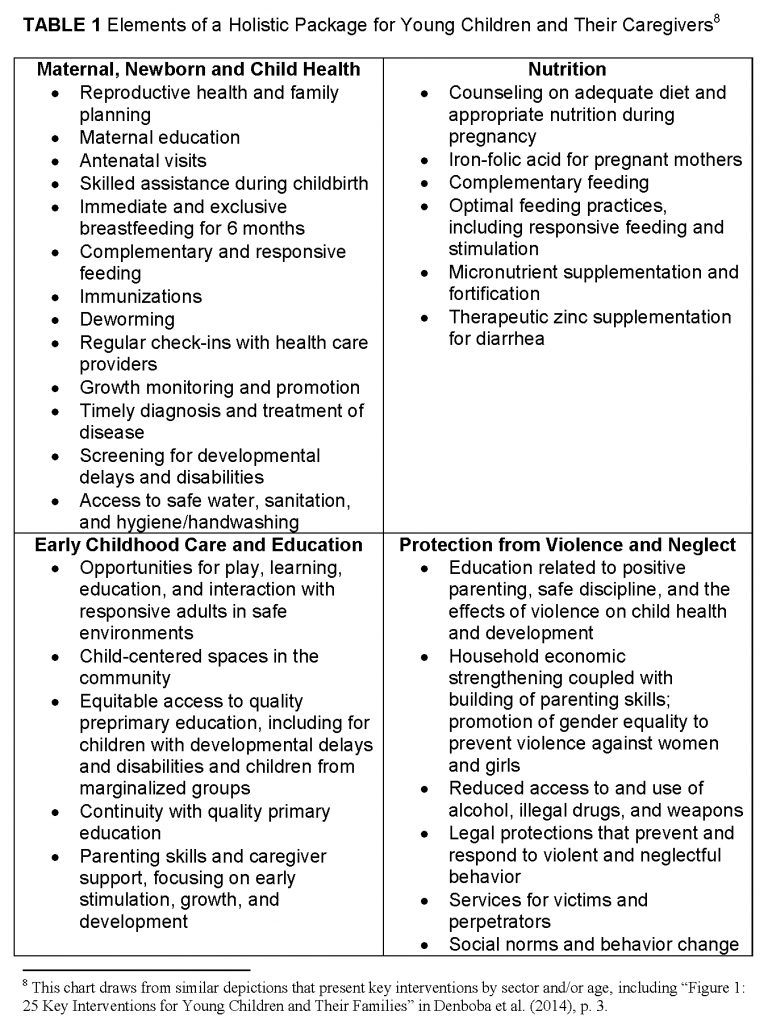

Co-locating and integrating services where possible; maximizing home visiting programs to address issues related to health, nutrition, and parent-child interactions; and creating effective referral mechanisms to close gaps between sectoral interventions and providers go a long way in ensuring that vulnerable children and families have the support they need to succeed. Table 1 summarizes elements of a holistic package of services for young children and their caregivers. While many programs focus on particular intervention or sectoral areas, noting the interlinkages within and across sectors is critical to ensuring children’s well-being across domains.

Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health

Science challenges the fundamental nature of programmatic stovepipes. For instance, there is growing international consensus within the public health community that early development is part of overall child health and is necessary for future prosperity. As far as long-term child outcomes are concerned, a narrow focus on child survival is insufficient. Maternal, newborn, and child health programs must also promote children’s developmental potential.

In 2013, Dr. Margaret Chan, director general of the World Health Organization (WHO), emphasized three areas critical for healthy child development: (1) stable, responsive, and nurturing caregiving with opportunities to learn; (2) safe and supportive physical environments; and (3) appropriate nutrition (Chan, 2013). Indeed, many of the strategies that support child development are the same as those that prevent morbidity and mortality (Engle et al., 2011; Jensen et al., 2015). Such interventions enhance and are absolutely consistent with the child survival agenda.

Primary and community health workers may be the first and only service providers to have contact with children during the first few years of life (Engle et al., 2013). Services targeting women and young children—family planning, prenatal care, safe birth practices, neonatal survival strategies, breastfeeding support, growth monitoring, immunizations—allow opportunities for introducing behaviors and practices that encourage healthy child development. As the WHO director general has stated, “The health sector therefore has a unique responsibility, because it has the greatest reach to children and their families during pregnancy, birth, and early childhood. The evidence is compelling to expand the child survival agenda to encompass child development” (Chan, 2013).

Indeed, strategies to prevent mortality in the first month of life—deaths that account for about half of all deaths in children under 5 years—are significant not only for survival but also for human capacity. “Failure to improve birth outcomes by 2035 will result in an estimated 116 million deaths, 99 million survivors with disability or lost development potential, and millions of adults at increased risk of non-communicable diseases after low birth weight. In the post-2015 era, improvements in child survival, development, and human capital depend on ensuring a healthy start for every newborn baby—the citizens and workforce of the future” (Lawn et al., 2014, p. 9938).

Foundations for healthy child development include many of the best practices that support child survival, including planned pregnancy and skilled assistance during childbirth; exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life followed by appropriate complementary and responsive feeding; timely diagnosis and treatment of infections and diseases; and preventive interventions, including vaccinations and regular check-ins with health care providers (Table 1). Nevertheless, these health practices, though critical for every child’s well-being, are insufficient on their own and must be reinforced with informed action across sectors (Chan, 2013).

Recognizing the need to equip health care workers with skills to promote holistic and healthy child development, UNICEF and WHO together created Care for Child Development, a landmark intervention that was originally developed in the late 1990s as part of the regular child health visits as specified in the WHO/UNICEF strategy of Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses (UNICEF and WHO, 2012). Since then, other initiatives have sought to integrate child survival, primary care, and child development, including Accelerated Childhood Survival and Development, Infant Young Child Feeding, and Maternal and Newborn Health Care. The Care for Child Development intervention provides information and recommendations for cognitive stimulation and social support to young children through sensitive and responsive caregiver-child interactions. It also guides health workers and other counselors as they help families build stronger relationships with their children and solve problems in caring for their children at home. These basic care-giving skills contribute to the survival, as well as the healthy growth and development, of young children (Elder et al., 2014).

Efforts to strengthen the capacities of vulnerable families to meet their children’s health and developmental needs in the midst of poverty or serious threat suggest two pathways. The first requires improved access to and utilization of preventive health services and treatment. The second requires bolstering children’s protective factors and capacity for resilience. Both involve supporting parents’ and caregivers’ ability to respond appropriately to children facing deprivation or distress. “The biology of adversity and resilience demonstrates that significant stressors, beginning in utero and continuing throughout the early years, can lead to early demise or produce long-lasting impacts on brain architecture and function” (Shonkoff et al., 2012).

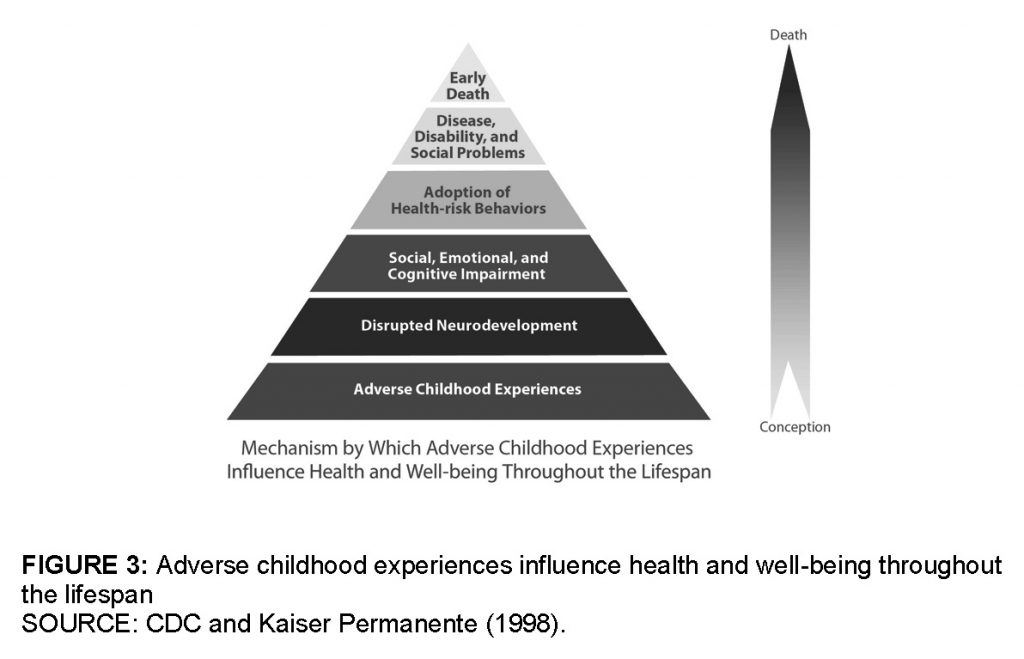

The effects of early adversity on long-term health have been shown through the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, one of the largest investigations ever conducted to assess associations between childhood adversity and later-life health and well-being (CDC and Kaiser Permanente, 1998). The study is a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente’s Health Appraisal Clinic in San Diego. The ACE Study’s findings suggest that certain experiences are major risk factors for the leading causes of illness and death as well as poor quality of life (see Figure 3). Though the study has focused on the United States, it is critical to understanding how some of the worst health and social problems can arise as a consequence of adverse childhood experiences. Realizing these connections is likely to improve efforts toward prevention and recovery, including doubling up efforts to strengthen children’s protective factors. Children who manage, and even do well, in the face of serious hardship typically have developed an array of adaptive capabilities embedded in neurobiological function, behavioral skills, relationships, and cultural or community connections. Resilience is the result of a combination of protective factors, which can be enhanced through strategic investments, including building the capabilities of caregivers and strengthening the communities that together form the environment of relationships essential to children’s lifelong learning, health, and behavior (Center on the Study of the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2015; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2015).

Nutrition

Good nutrition is fundamental to child health and well-being, beginning with a mother’s nutritional status before and during pregnancy (UNICEF, 2013). Proper nutrition is a key element in combating child mortality and morbidity: approximately 45 percent of all deaths of children under the age of 5 in low-income countries are attributable to undernutrition (WHO, 2016). Beyond its role in ensuring survival, the association between nutrition in early life and long-term health has been of interest for decades (Bhutta, 2013). The biological and epidemiological linkages between various types of undernutrition (stunting, wasting, and micronutrient deficiencies) and impaired cognitive development in the early years is well established (Black and Dewey, 2014). Nutrition plays a key role in healthy child development, particularly in the early years as neurodevelopmental building blocks are being formed and nutritional needs are high (Ramkrishnan et al., 2011). The effect of poor nutrition on young children, particularly between ages 0–8, and most acutely during the 1,000-day period from conception to age 2 years, can be devastating and enduring, having serious implications for health, behavioral and cognitive development, future reproductive health, and future workforce productivity.

Poor nutrition can lead to stunting, a condition that is defined as height for age below the fifth percentile on a reference growth curve. Stunting is used as a measure of nutritional status and serves as an important indicator for chronic undernutrition. Factors contributing to stunting include poor maternal health and nutrition before, during, and after pregnancy, as well as inadequate infant feeding practices, particularly during the 1,000 days from conception through a child’s second birthday (WHO, 1997). Stunting early in life seriously affects brain functioning and can cause permanent cognitive impairment. As a result, it has been associated with consequences that threaten equity throughout the life cycle, including diminished health, poor school performance and early termination, and reduced work capacity and future earning potential (Hoddinot et al., 2013). Malnutrition adds staggering health costs for already financially burdened countries.

Early stunting has been used as an indicator, along with poverty, to estimate the number of children who are at risk for not reaching their developmental potential. Currently, nearly one in four children under age 5 worldwide is stunted. This massive burden poses serious threats to individual and community capacity for health, stability, and productivity. The vast majority of the 159 million children under age 5 who are stunted live in Asia and Africa (UNICEF, 2015). The good news is that global stunting prevalence has declined from nearly 40 percent in 1990 to 24 percent in 2014.

Nearly 20 years of research has demonstrated that nutrition programs that are combined with health, water and sanitation, and child development interventions—emphasizing stimulating and responsive parenting—achieve greater immediate and long-term effects (Black and Dewey, 2014). A groundbreaking randomized controlled trial in Jamaica revealed that stunted children who received targeted nutrition interventions alongside support for parents had better outcomes than children receiving only nutrition interventions. A 20-year follow-up shows that the stunted Jamaican toddlers who received 2 years of psychosocial stimulation had higher IQs and experienced reduced anxiety and depression and less violence. Strikingly, their future earnings were 50 percent greater than the nonstimulated stunted group. In fact, their earnings were comparable to a nonstunted sample, indicating that the stimulation intervention enabled them to catch up to their well-nourished peers (GranthamMcGregor et al., 1997 and 2007; Gertler et al., 2014).

In 2014, more than 80 leading researchers from multiple disciplines consolidated the existing evidence to advance knowledge concerning an integrated approach to improving both nutrition and early childhood development. The resulting collection of 20 articles provides a portrayal of the current state of the science linking brain development, psychology, nutrition, and growth, reviewing the impact and lessons learned from integrated interventions to improve outcomes across these domains (Black and Dewey, 2014). It is essential that current policies and programs take this learning into consideration and that funding is used to support evidence-based programming rather than unintegrated program siloes that sever children’s needs into separate and uncoordinated services.

Early Childhood Care and Education

Young children’s growth and development are profoundly shaped by nurturing care and opportunities for play, learning, education, and interaction with responsive adults—whether these occur at home, in out-of-home caregiving environments, such as child care centers, or in formal or informal child-centered spaces and educational settings in the community (Britto et al., 2013; Ginsburg, 2007). These early interactions lay the groundwork for developmental potential, including physical, cognitive, social, and emotional growth. Skills required for schooling, employment, and family life build cumulatively on these dimensions of developmental potential. Indeed, nurturing early childhood care and education are fundamental to quality basic education and serve as a foundation for equity (Irwin et al., 2007).

Significant disparities in early learning experiences for low-income children can set the stage for achievement gaps that persist through years of school and lead to a lifetime of missed opportunities, inequities, and even health challenges. Increasing access to quality early childhood care and education is considered an effective “equalizer” (Irwin et al., 2007). Research from developing countries shows that early childhood development programs lead to higher levels of primary school enrollment and educational performance, which in turn positively affect employment opportunities later in life. On the contrary, children who start school late and lack the necessary skills to be able to learn constructively are more likely to fall behind or drop out completely, often perpetuating intergenerational cycles of poverty (Engle et al., 2011). Studies show that the returns on investments in early childhood care and education are highest among poorer children, for whom these programs may serve as a stepping stone out of poverty or exclusion (Heckman, 2006).

Despite the proven benefits of early childhood care and education programs, access and attendance remain very low in many developing countries, particularly for children from marginalized populations, including children with disabilities. Attendance in early learning programs among children ages 3 and 4 is less than 50 percent in the majority of countries with available data (UNICEF, 2016). Low attendance is related to limited access—a direct result of the lack of prioritization placed on early childhood programs—and associated minimal funding.

Inadequate attention to the foundational early childhood period has affected global efforts to achieve basic targets in education. Fortunately, the previous lack of focus on early childhood development has been addressed in the post-2015 global development agenda. Target 4.2 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, announced in September 2015, states that, by 2030, “all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education” (United Nations, 2015). The challenges involved in achieving universal access to early childhood development programs are enormous, particularly given ingrained patterns of underinvestment in this area.

The economic science is clear and compelling: investments in learning and development during the early years result in greater cost savings than investments made later in the life cycle (Heckman, 2008). According to the World Bank, high-income countries spend an estimated 1.6 percent of their gross domestic product (GDP) on family services and preschool for children aged 0–6 years and 0.43 percent of GDP on preschools alone. By comparison, low-income countries tend to spend far less than 0.1 percent on preschools (Engle et al., 2011). Yet, even in resource-rich countries, developmental vulnerability increases as socioeconomic status decreases (Irwin et al., 2007). Increasing preschool enrollment rates to 25 percent could yield an estimated $10.6 billion through higher educational achievement, and a 50 percent increase could generate $33.7 billion (Engle et al., 2011). Such investments in preprimary environments yield even greater dividends when coupled with community-based health and nutrition programs and parenting support. Unless governments—including bilateral agencies—allocate increased resources to quality early childhood care and education programs, and, in particular, target children in the lowest economic quintile, economic disparities will continue and widen.

Protection from Violence and Neglect

Over the last few decades, knowledge has accumulated about how normative child development can be significantly derailed by exposure to violence and neglect, particularly when such exposure is repeated or chronic (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2016). Science shows that early exposure to maltreatment can disrupt healthy development and have lifelong consequences (Cicchetti and Toth, 2016; Pollak, 2015). Research also shows that violence against women and children often co-occur and share common risk factors (Patel, 2011). Women who experience violence from their partners are more prone to depression and less likely to earn a living or provide consistent and nurturing care for their children (National Resource Center on Domestic Violence, 2002). Fortunately, effective strategies to prevent violence against women and children are becoming more fully understood and utilized (WHO, 2010; Bernard van Leer Foundation, 2011; KNOW Violence, undated).

Child maltreatment includes experiencing violent discipline, witnessing intimate partner violence, and being neglected by caregivers (Hillis et al., 2015). Caregivers’ failure to provide sufficient and adequate nutrition, clothing, shelter, sleep, or medical care and to ensure that the child’s surroundings and activities are responsive, nurturing, and safe all constitute forms of neglect toward a child, leading to more severe deprivations over time. Research has demonstrated that healthy child development can be derailed not only as the result of physical or sexual abuse but also by the lack of sufficient quality experiences, nurturing, and opportunities to learn, particularly in the early years (Cicchetti, 2013). Despite neglect being, by far, the most prevalent form of child maltreatment, it receives far less public attention than physical or sexual abuse (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2012).

When caregiver or other adult responses to children are violent, erratic, inappropriate, or simply absent, developing brain circuits can be disrupted, affecting how children learn, solve problems, and relate to others (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2012). Such experiences, particularly in the sensitive period of early childhood, can lead to lasting physical, mental, and emotional harm with long-term effects. Affected children are more likely to suffer from attachment disorders, regressive or aggressive behavior, depression, and anxiety. Child maltreatment and other adverse experiences can affect immediate and long-term health, cognitive function, and socioemotional well-being (Margolin and Elana, 2004; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2010a). Violence and neglect often cycle through generations, negatively affecting individual and collective opportunities for productivity and health over many years.

A first step in preventing violence and neglect is better understanding their magnitude, nature, and consequences. The CDC’s Violence against Children Surveys measure physical, emotional, and sexual violence against girls and boys. The surveys’ data have been released in eight countries, with data collection ongoing in several more (CDC, undated). In early 2016, the CDC released a groundbreaking report estimating the global burden of violence against children throughout the world. The study combines data from 38 reports spanning nearly 100 countries to calculate the number of children affected by violence in the past year. Conservative estimates of the data show that a minimum of 50 percent of children in Asia, Africa, and North America experienced serious forms of violence and that more than half of all children in the world—1 billion children ages 2–17 years—are victims of violence, subjected to regular physical punishment by their caregivers (Hillis et al., 2015). An estimated 275 million children witness domestic violence every year. Often, intimate partner violence tends to co-occur with the direct victimization of children (UNICEF, 2014b). Further exposure is detailed in a statistical analysis of violence against children released by UNICEF in 2014, shedding light on the prevalence of different forms of violence against children, with global figures and data from 190 countries (UNICEF, 2014b). Where relevant, data are disaggregated by age and sex to provide insights into risk and protective factors.

The prevalence of violence experienced by children ages 0–8 is difficult to assess because much of the violence occurs within the privacy of individual homes, child care centers, and residential institutions, and thus is often hidden from public view. Caregivers committing violence against children are unlikely to self-report or seek help, particularly where violent discipline is a cultural norm or a social taboo. In lower-income countries, social services are minimal and underresourced, often ill-equipped to assess or effectively respond to violence against children. In addition, existing data-collection mechanisms lack age-appropriate diagnostic tools for children under 15 years of age (Bernard van Leer Foundation, 2012). Nevertheless, data show that the first year is the most dangerous period in a child’s life with respect to the risk to survival not only from neonatal causes but also from violence, abuse, and neglect (Da Silva e Paula et al., 2013).

The economic costs associated with neglect of and violence against children can be broadly divided into two categories: direct and indirect. The direct costs are more immediate and easier to measure, including (1) health care costs associated with treatment of physical injuries and psychological and behavioral problems; (2) social welfare costs incurred for monitoring, preventing, and responding to neglect of and violence against children; and (3) criminal justice costs associated with ensuring that perpetrators are punished and that victims are protected. Indirect costs may be less obvious, but loom much larger. These include significant losses in future productivity arising from the negative and often irreversible impact that childhood neglect and violence have on child development and well-being. Adults who experienced violence and/or neglect in childhood have lower levels of education, more limited opportunities for employment, lower earnings, and fewer assets. The adverse experiences in early childhood significantly reduce human capital formation, with serious repercussions for individuals, families, and societies as a whole (Santos Pais, 2015; Berens and Nelson, 2015).

Studies of costs associated with violence against children reference the proportion of gross national income/gross domestic product potentially lost due to expenditure on response, prevention, and productivity losses. Estimates vary depending on the types of violence studied and how comprehensively the direct and indirect costs are assessed. Even when these assumptions are taken into consideration, the lowest estimates at national, regional, or global levels indicate that costs range between 2 and 10 percent of GDP, representing a significant cost to national and global economies (Fearon and Hoeffler, 2014). One study estimates that the global economic impacts and costs resulting from the consequences of physical, psychological, and sexual violence against children can be as high as $7 trillion. This massive cost is higher than the investment required to prevent much of that violence (Pereznieto et al., 2014).

We can take steps to protect the world’s children from violence and neglect. Data show that the following strategies are effective in preventing both: teaching positive parenting skills; economically empowering households; reducing violence and neglect through protective policies; improving health, child protection, and support services; changing the social norms that support violence; and teaching children social, emotional, and life skills. These strategies are based on CDC’s core package THRIVES (Hillis, 2015) and similar guidance from UNICEF and WHO (UNICEF, 2014a) and are in support of the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Goal to “end all forms of violence against children” (Hillis et al., 2016).

Violence prevention and response interventions have typically focused on school-aged children through programs in schools and communities. More can be done to empower actors across multiple sectors who provide services targeting young children and their families to play a key role in preventing maltreatment and neglect in children’s early and most formative years. Nevertheless, although the evidence clearly shows that “prevention pays,” current levels of spending on preventive and responsive actions in relation to violence against and neglect of children remain very low (Pereznieto et al., 2014).

Families on the Front Lines: Supporting Caregivers

To truly eradicate poverty and foster equity and to seriously put children at the heart of the global development agenda, we must recognize and support the critical role that families—which are, by nature, broadly defined—play in promoting children’s health, development, education, and protection. Services delivered to children—whether primary health and nutrition care, early childhood care and development, education, or protection—do not work in a vacuum. They are most effective when they consider the vital role of family in children’s lives and well-being. Without the consistent, nurturing and protective care of parents and caregivers, children’s well-being suffers across domains.

Empowering Women, Supporting Children

Women’s and children’s rights have been bifurcated by advocates and policy makers for decades, but in many ways they are indivisible in the real lives of many women and children. This is not to suggest that the promotion of women’s empowerment and children’s rights are entirely interchangeable. Whether seen as separate or complementary causes, it is important that children are not left out of the equation as workplace and economic productivity or women’s empowerment and well-being are promoted.

The link between a mother’s education, health, nutrition, psychosocial wellness, safety, and socioeconomic status and her children’s well-being is inextricable. Maternal, newborn, and child health programs are therefore often co located. Yet, beyond the health sector, a gap begins to emerge between that which is done to promote women’s empowerment and that which is done to support children.

For instance, quality and affordable child care is a critical part of advancing women’s full participation in economic, political, and civic life, yet it is often missing from policy discourse and program implementation. As any working parent can attest, quality child care is a critical link between efforts to promote employment opportunities and holistic child well-being, particularly for poor working families (Heymann, 2006). Pursuing fundamentally separate agendas for women and children can be a disservice to both.

Indeed, labor policies that either facilitate or hinder working adults’ ability to balance work and caregiving responsibilities have a particularly large impact on women and children. Paid maternity—or, more preferably parental leave is a key first step, though caregiving does not end at infancy. Finding affordable and quality child care that meets the needs of children and working parents remains difficult worldwide, particularly in low-income countries. Huge gaps in access persist, quality is often substandard, and laws and policies to regulate care are often nonexistent or unenforced (Clinton Foundation and Gates Foundation, 2015).

As a result, the number of young children who are left without adult care while their parents work long hours outside of the home continues to grow. This situation negatively affects the health, development, and safety of these children, impacting their future potential as well as the ability of working parents to be fully productive. According to results from UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, more than 17 percent of children under age 5 are left home alone or in the care of another child under the age of 10 (UNICEF, 2012). Poor families are more likely to leave a child in inadequate care than wealthier families, and children from the poorest families are two times less likely to attend an organized early childhood care and education program than the richest families (UNICEF, 2012).

The Safety Net

Improving workplace policies and child care opportunities is important but insufficient, especially for the poorest families who work as part of the informal economy where workplace policies are essentially irrelevant. When vulnerable parents and families are unable to cope on their own, broader systems of support are often necessary. Social protection systems are central to reducing poverty and can have a direct and positive impact on poor families by improving access to better health, more schooling, economic assistance, and skills building. Effective and well-functioning social service and child welfare systems are vital to a nation’s social and economic progress and are as important to global development programs as are strong health systems. Yet, in most low-income countries, these systems are understaffed and underresourced. The human resource constraint is critical. With proper investments and training, social service workers are able to help ensure that effective prevention and support services are available to the most vulnerable populations. Social service providers work to register births, connect families with essential services, prevent family-child separation, support alternative care, reunite families, provide critical psychosocial support, and link vulnerable families and parents with social protection schemes and economic strengthening activities (Global Social Service Workforce Alliance, 2015).

Globally, researchers, policy makers, and program implementers have increasingly recognized that family strengthening for the poorest families is key to effective responses to ensure healthy and holistic child development and protection. Economic assistance is a core aspect of a family-strengthening approach. Household economic-strengthening interventions target the family as the beneficiary and include interventions that focus on increasing access to household savings, credit, income generation, and employment opportunities. For example, conditional cash-transfer programs provide money to poor families to target poverty and increase family capital contingent on caretakers engaging in certain target behaviors, such as sending children to school, taking them for health clinic visits, and ensuring vitamin supplements and nutritious food. There is promising evidence regarding the benefits of conditional cash transfer programs for families with young children (Elder et al., 2014). A review of nearly 50 published or publicly available randomized controlled trial research studies on household economic-strengthening interventions confirmed mostly positive effects on children’s outcomes, including improved nutrition status and increased enrollment in education (Chaffin and Mortensen Ellis, 2015). The review also illustrated how conditional cash transfers can have secondary and longer-term positive impacts on children beyond those stipulated in the conditions of the cash transfer, including reduced sexual activity in adolescence and lower levels of psychological distress. Still, implementation of cash transfer programs—whether conditional or unconditional—varies considerably, and mixed results from some programs require further consideration (Chaffin and Mortensen Ellis, 2015). Research has helped to identify a combination of interventions that effectively lift vulnerable households out of poverty and improve caregiving environments, resulting in positive and measurable outcomes for children across domains.

The Ultimate Breakdown: Children Living Outside of Family Care

When vulnerable parents and families do not have the resources to meet basic needs, the risk of child neglect and separation from the birth family increases. Extreme poverty and inadequate access to basic services have led to millions of children living outside of family care—in institutions, on the street, trafficked, or separated from their families as a result of conflict, disaster, forced labor, or disability (Maholmes et al., 2012). These children have largely fallen off the world’s statistical maps (Clay et al., 2011). For instance, there is currently no global data on the numbers of children living in institutions. Estimates range from 2 to 8 million, but the actual number of orphanages or residential institutions and the number of children living in them are unknown. Many institutions are unregistered, and underreporting is widespread. No international monitoring frameworks exist, and many countries do not routinely collect or monitor data on institutionalized children (Berens and Nelson, 2015).

The fact is, we measure what we care about, and we care about what we measure. Given the inextricable links among data, advocacy, and strategic action—not to mention the extraordinarily negative effects of spending early childhood without the nurturing and protective care of a permanent caregiver—this kind of invisibility has real-life repercussions for the world’s most vulnerable children.

Strengthening families must be a global priority if we are serious about promoting children’s well-being from survival to thrival. With inadequate investments in families, it will be impossible to reduce child morbidity and mortality, improve educational outcomes, and protect children from violence, exploitation, and abuse. Yet, despite the critical role families play in children’s lives, they receive short shrift in global development policies and programs. The one passing reference to “families” in the United Nation’s new sustainable development goals is a case in point (United Nations, 2015). It has been said that family is like oxygen—taken for granted until it is gone. Children do not fare well without at least one stable and committed relationship with a supportive parent, caregiver, or other adult. We cannot truly support children without investing in these relationships (Richter and Naicker, 2013).

Protecting the Future Through Strategic Investment

As global scientific and development communities continue to learn more about what works to promote children’s optimal health, development, and protection, there is growing recognition of the need to finance successful programs beyond the pilot stage and take them to scale at the national level. A funding gap to support comprehensive early childhood programs has existed for some time. Given the strong evidence base and “proof of concept,” it is time to close it (IOM/NRC, 2015).

Improving investments in coordinated programs for children ages 0–8 requires harmonization across funding streams and sectoral siloes. Child development is multidimensional and therefore requires multisectoral investments. As a promising example, the World Bank has been increasing support for integrated early childhood programs in recent years. Between 2001 and 2013, it invested $3.3 billion in early childhood programs through health, education, and social protection programs targeting pregnant women, young children, and their families. The World Bank has also invested substantially in research and impact evaluations concerning programs for children ages 0–8, focusing on early childhood nutrition, health, and development and expanding the evidence base on effective, quality, and scalable interventions (World Bank, 2014; Denboba et al., 2014). In April 2016, the World Bank and UNICEF jointly launched a global alliance on early childhood development (Kim, 2016). Prioritization of early childhood development is also occurring on the U.S. domestic front, with U.S. tax dollars allocated to early childhood programs through the Departments of Education and Health and Human Services (U.S. Office of Management and Budget, 2016).

Nevertheless, similar levels of attention and prioritization have yet to be seen in the realm of U.S. government foreign assistance programs. Indeed, U.S. international assistance to children is substantial and channeled through offices in multiple U.S. government departments and agencies—the Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Health and Human Services, Labor, and State; the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID); and the Peace Corps (U.S. Government, 2014). Yet, to date, limited funds have been set aside for early childhood development per se.

Public Law 109-95, titled the Assistance for Orphans and Other Vulnerable Children in Developing Countries Act of 2005, was signed into law to promote a comprehensive, coordinated, and effective response on the part of the U.S. government to the world’s most vulnerable children (U.S. Congress, 2005). It calls for an interagency strategy and a whole-of-government monitoring and evaluation system. The act also establishes a special advisor, currently based at the USAID, but the position comes with no oversight or funding authority.

In 2012, in accordance with Public Law 109-95, the U.S. government released the Action Plan on Children in Adversity, the first whole-of-government strategic guidance for U.S. international assistance programs (U.S. Government, 2012). The plan is grounded in evidence that shows that a promising future belongs to those nations that invest wisely in their children, while failure to do so undermines social and economic progress. It states that child development is a cornerstone for all development and therefore central to U. S. development and diplomatic efforts. The action plan seeks to achieve three principal objectives: (1) Build strong beginnings; (2) Put family care first; and (3) Protect children from violence, exploitation, abuse, and neglect. Multiple offices within 11 U.S. government departments and agencies agreed to specific actions to implement the plan.

No dedicated funding was appropriated to implement the plan until fiscal year 2015. Since then, appropriations’ report language has suggested that approximately $10 million per year be directed toward its implementation. Annual reports to Congress suggest that multiple U.S. government offices contribute broadly to the plan’s objectives, though details related to inputs and outcomes are slim. One of the action plan’s strengths is its focus on measurable results, specifically achieving significant reductions in the number of children not meeting age-appropriate growth and developmental milestones; children living outside of family care; and children who experience violence or exploitation. Despite these laudable goals, it would appear that few U.S. government programs are tracking these outcomes (U.S. Government, 2014).

U.S. government appropriations continue to provide robust support for important global health, nutrition, and education programs (Kaiser Family Foundation, undated), though none of the corresponding funding directives includes language to support investments specifically in early childhood development. The one exception is the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which has a 10 percent setaside for Orphans and Vulnerable Children’s (OVC) Programming, which has historically promoted integrated programs for children affected by HIV and AIDS. In 2016, House report language recommended that PEPFAR integrate the action plan’s “Strong Beginnings” objective into programs for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. In addition, Senate report language directed that up to $20 million of OVC program funds be used for children living outside of family care (U.S. Congress, 2015b).

The lack of explicit reference to the importance of integrated and coordinated cross-sectoral investments in early childhood development in funding directives and strategies for the U.S. government’s foreign assistance portfolio has meant that such activities are not prioritized or do not occur at all. Despite significant investments in maternal, newborn, and child health and nutrition programs and the synergies that exist between such investments and child development outcomes, the USAID’s Bureau for Global Health, which is home to maternal and child health and nutrition programs, currently does not track funding, programming, or outcomes related to early childhood development (U.S. Government, 2014). Nor has early childhood development been included in the USAID’s education strategy (USAID, 2011). In a more hopeful vein, the USAID’s nutrition strategy recognizes the important linkages between appropriate nutrition and the holistic growth, health, and development of young children (USAID, 2014). A similar lack of prioritization exists within other U.S. government international assistance programs. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which does significant work to prevent child morbidity and mortality, has received no appropriations to continue its important work conducting Violence against Children Surveys or to implement its corresponding program, THRIVES. The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development supports important research related to child health and development, but there is currently no established feedback loop to ensure that science is informing U.S. government international programs and policies. Of note, the Department of State has no office, ambassador, or other high-level appointee to represent global children’s issues. (The State Department’s Special Advisor for Children’s Issues oversees intercountry abduction and adoption only.)

As a result, those attempting to deliver integrated programs for young children at the country level are left to stitch together a patchwork quilt of funding from separate and uncoordinated donor sources. This has serious implications for programmers who are committed to providing comprehensive services to the most vulnerable households and families. It also creates complications for those attempting to measure and assess the overall impact of U.S. government international assistance to young children.

A Concluding Call to Action

With its significant investments in international development, the technical expertise and research capabilities embedded within key agencies, and diplomatic outreach, the U.S. government is well-positioned to lead and mobilize around a sensible and strategic global agenda for young children. Child development is, after all, one of the world’s greatest challenges in scope, scale, and impact. The persistent lack of attention to child development in policies and programs threatens the socioeconomic fabric of nations. The failure to invest in the developmental potential of children locks families, communities, and nations into poverty and threatens global security. Evidence from across disciplines—from neuroscience to biological and developmental science to economic science—has clearly demonstrated that investing in young children’s holistic well-being is a proven pathway out of poverty and into promise. It is past time to take that road.

Download the graphic below and share it on social media!

References

- Berens, A. E., and C.A. Nelson. 2015. The science of early adversity: Is there a role for large institutions in the care of vulnerable children? Lancet, January 29 (online). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61131-4.

- Bernard van Leer Foundation. 2011. Hidden violence: Protecting young children at home. The Hague: Bernard van Leer Foundation. Available at: http://resourcecentre.savethechildren.se/sites/default/files/documents/4665.pdf (accessed July 20, 2020).

- Bernard van Leer Foundation. 2012. Stopping it before it starts: Strategies to address violence in young children’s lives. The Hague: Bernard van Leer Foundation.

- Bhutta, Z. 2013. Early nutrition and adult outcomes: Pieces of the puzzle. Lancet 382(9891):486–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60716-3

- Black, M., and K. Dewey, eds. 2014. Every child’s potential: Integrating nutrition and early childhood development interventions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1308: 1-255. Available at: https://www.nyas.org/annals/every-child-s-potential-integrating-nutrition-and-early-childhood-development-interventions/ (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Boothby, N., R. L. Balster, P. Goldman, M. G. Wessells, C. H. Zeanah, G. Huebner, and J. Garbarino. 2012. Coordinated and evidence-based policy and practice for protecting children outside of family care. Child Abuse and Neglect: The International Journal, 36(10): 743-751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.09.007

- Britto, P. R., P.L. Engle, and C.M. Super, eds. 2013. Handbook of early childhood development research and its impact on global policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carneiro, P. M., and J. J. Heckman. 2003. Human capital policy. IZA Discussion Paper No. 821. Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=434544 (accessed July 22, 2020).

- CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Undated. Violence against children surveys. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/vacs/index.html (accessed July 22, 2020).

- CDC and Kaiser Permanente. 1998. The adverse childhood experiences study. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/index.html (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. 2012. The science of neglect: The persistent absence of responsive care disrupts the developing brain. Working Paper No. 12. Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/the-science-of-neglect-the-persistent-absence-of-responsive-care-disrupts-the-developing-brain/ (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. 2014. A decade of science informing policy: The story of the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/decade-science-informing-policy-story-national-scientific-council-developing-child/ (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. 2015. The science of resilience (In Brief). Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-the-science-of-resilience/ (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. 2016. Neglect (Deep Dives). Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/deep-dives/neglect/ (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Undated. Brain architecture. Available at: http://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/brain-architecture/ (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Chaffin, J., and C. Mortenson Ellis. 2015. Outcomes for children from household economic strengthening interventions: A research synthesis. Child Protection in Crisis Learning Network and Women’s Refugee Commission for Save the Children UK. Available at: http://www.cpcnetwork.org/resource/outcomes-for-children-from-household-economic-strengthening-interventions/ (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Chan, M. 2013. Linking child survival and child development for health, equity, and sustainable development. Lancet 381:1514–1515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60944-7

- Cicchetti, D. 2013. Annual research review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children—past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 54:402–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x

- Cincchetti, D., and S. L. Toth. 2016. Child maltreatment and developmental psychopathology: A multilevel perspective. In Developmental Psychopathology, 3rd ed., Vol 3, edited by D. Cincchetti. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Pp. 513–563.

- Clay, R., L. C. deBaca, K. M. De Cock, E. Goosby, A. Guttmacher, S. Jacobs, A. Pablos-Mendez, S. Polaski, G. Sheldon, and D. Steinberg. 2011. A call for coordinated and evidence-based action to protect children outside of family care. Lancet, December 12 (online). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61821-7

- Clinton Foundation and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. 2015. No ceilings: The full participation report. Available at: http://noceilings.org/report/report.pdf (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Da Silva e Paula, C., C. Landers, and T. Kilbane. 2013. Preventing violence against young children. In Handbook of early childhood development research and its impact on global policy, edited by P. R. Britto, P. L. Engle, and C. M. Super. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Denboba, A. D., L. K. Elder, J. Lombardi, L. B. Rawlings, R. K. Sayre, and Q. T. Wodon. 2014. Stepping up early childhood development: Investing in young children for high returns. The World Bank Group and Children’s Investment Fund. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2014/10/20479606/stepping-up-earlychildhood-development-investing-young-children-high-returns (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Elder, J. P., W. Peguegnat, S. Ahmed, G. Bachman, M. Bullock, W. A. Carlo, V. Chandra-Mouli, N. A. Fox, S. Harkness, G. Huebner, J. Lombardi, V. M. Murry, A. Moran, M. Norton, J. Mulik, W. Parks, H. H. Raikes, J. Smyser, C. Sugg, M. Sweat, and N. Ulkuer. 2014. Caregiver behavior change for child survival and development in low- and middle-income countries: An examination of the evidence. Journal of Health Communication 19 (supp. 1): 25–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.940477

- Eloundou-Enyegue, P. 2014. Comment, Institute of Medicine Forum on Investing in Young Children Globally: The Cost of Inaction for Young Children Globally, Washington, DC.

- Engle, P. L., L. C. H. Fernald, H. Alderman, J. Behrman, C. O’Gara, A. Yousafzai, M. Cabral de Mello, M. Hidrobo, N. Ulkuer, I. Ertem, and S. Iltus. 2011. Strategies for reducing inequalities and improving developmental outcomes for young children in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 378 (9799): 1339 –1353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60889-1

- Engle, P. L., M. E. Young, and G. Tamburlini. 2013. The role of the health sector in early childhood development. In Handbook of early childhood development research and its impact on global policy, edited by P. R. Britto, P. L. Engle, and C. M. Super. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Evans, G. W., D. Li, and S. Sepanski Whipple. 2013. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin 139(6)1342–1396. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031808

- Fearon, J., and A. Hoeffler. 2014. Conflict and violence assessment paper: Benefits and costs of the conflict and violence targets for the post-2015 development agenda. Copenhagen, Denmark: Copenhagen Consensus Center.

- Gertler, P., J. Heckman, R. Pinto, A. Zanolini, C. Vermeersch, S. Walker, S. M. Chang, and S. Grantham-McGregor. 2014. Labor market returns to an early childhood stimulation intervention in Jamaica. Science 344:998–1001. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1251178

- Ginsburg, K. R. 2007. The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics 119(1): 182-191. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2697

- Global Social Service Workforce Alliance. 2015. The state of the social service workforce 2015 report: A multi-country review. Available at: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/state-social-service-workforce-2015-report-multi-country-review (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Grantham-McGregor, S., S. P. Walker, S. M. Chang, and C. A. Powell. 1997. Effects of early childhood development supplementation with and without stimulation on later development in stunted Jamaican children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 66(2): 247-253. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/66.2.247

- Grantham-McGregor, S., Y. B. Cheung, S. Cueto, P. Glewwe, L. Richter, and B. Strupp. 2007 Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet 369(9555):60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4

- Heckman, J. J. 2006. Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science 312(5782):1900–1902. Available at: http://jenni.uchicago.edu/papers/Heckman_Science_v312_2006.pdf (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Heckman, J. J. 2007. The economics, technology, and neuroscience of human capability formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104(33):13250–13255. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701362104

- Heckman, J. J. 2008. Schools, skills and synapses. Economic Inquiry 46(3):289–324. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w14064 (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Heckman, J. J. Undated. Invest in early childhood development: Reduce deficits, strengthen the economy. Available at: https://heckmanequation.org/resource/invest-in-early-childhood-development-reduce-deficits-strengthen-the-economy/ (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Heymann, J. 2006. Forgotten families: Ending the growing crisis confronting children and working parents in the global economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hillis, S. D., J. A. Mercy, J. Saul, J. Gleckel, N. Abad, and H. Kress. 2015. THRIVES: A global technical package to prevent violence against children. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/31482/cdc_31482_DS1.pdf (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Hillis, S., J. Mercy, A. Amobi, and H. Kress. 2016. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review of minimum estimates. Pediatrics 137(3):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4079

- Hoddinot, J., J. R. Behrman, J. A. Maluccio, P. Melgar, A. R. Quisumbing, M. Ramirez-Zea, A. D. Stein, K. M. Yount, and R. Martorell. 2013. Adult consequences of growth failure in early childhood. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 98:1170–1178. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.064584

- IHME (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation). 2014. Financing global health 2014: Shifts in funding as the MDG era closes. University of Washington, Seattle. Available at: http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/policy_report/2015/FGH2014/IHME_PolicyReport_FGH_2014_0.pdf (accessed July 22, 2020).

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2000. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9824

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2014. The Cost of Inaction for Young Children Globally: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18845

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. 2014. Financing Investments in Young Children Globally: Workshop in Brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21684

- Irwin, L. G., A. Siddiqi, and C. Hertzman. 2007. Early childhood development: A powerful equalizer. Available at: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/ecd_kn_report_07_2007.pdf (accessed July 22, 2020).