The Promise of Population Health: A Scenario for the Next Two Decades

In my 1997 book Purchasing Population Health: Paying for Results, I was either bold or foolish to make the following predictions about how the next two decades of work and progress in improving population health might proceed (Kindig, 1997):

Phase 1 (1998–2002): Research and Debate. Over the next five years, research and demonstration efforts should begin to build the empirical and experiential base that improving population health by financially incentivizing improvements requires.

Phase 2 (2003–2010): Fully Integrated Medical Delivery Systems. The first step is to move to fully integrated (seamless) medical care systems that go beyond hospital and physician integration to include prevention, primary care, long-term care, and health education. Financial incentives need to put at risk and reward those systems for health-adjusted life expectancy improvements that are under their control.

Phase 3 (2011–2020): Integrating the Multiple Determinants of Health. The fuller integration in the United States of the largely private medical care systems and the largely public other determinant sectors will await forms of integration across these sectors that have not yet developed either in theory or practice.

At the time, the book noted that these steps did not have to take place sequentially, but aligning incentives with outcomes was so new and challenging that sequential steps seemed simpler to communicate. Unfortunately, these were clearly stretch goals; some progress has been made in each area, particularly regarding value purchasing in medical care, but we are still far from “paying for results” (Kindig et al., 2018; Magnan and Kindig, 2019; McCullough et al., 2020). For example, the American health care system pays for processes (e.g., use of drugs, tests, and procedures) but not for improvement in outcomes such as life expectancy, healthy days, life satisfaction, and mental health. There is growing attention regarding the integration of the multiple determinants of health, and incremental progress is being made at select health care organizations and other super-integrators, but not at the comprehensive level I had envisioned and is needed (CMS, 2022; Magnan, 2021).

A decade later, “Understanding Population Health Terminology” ended with this sentence (Kindig, 2007):

“the (emphasis added) overriding population health question is, what is the optimal balance of investments (e.g., dollars, time, policies) in the multiple determinants of health (e.g., behavior, environment, socioeconomic status, medical care, genetics) over the life course that will maximize overall health outcomes and minimize health inequities at the population level? This is a significant challenge that will require decades of attention by scholars and policymakers.”

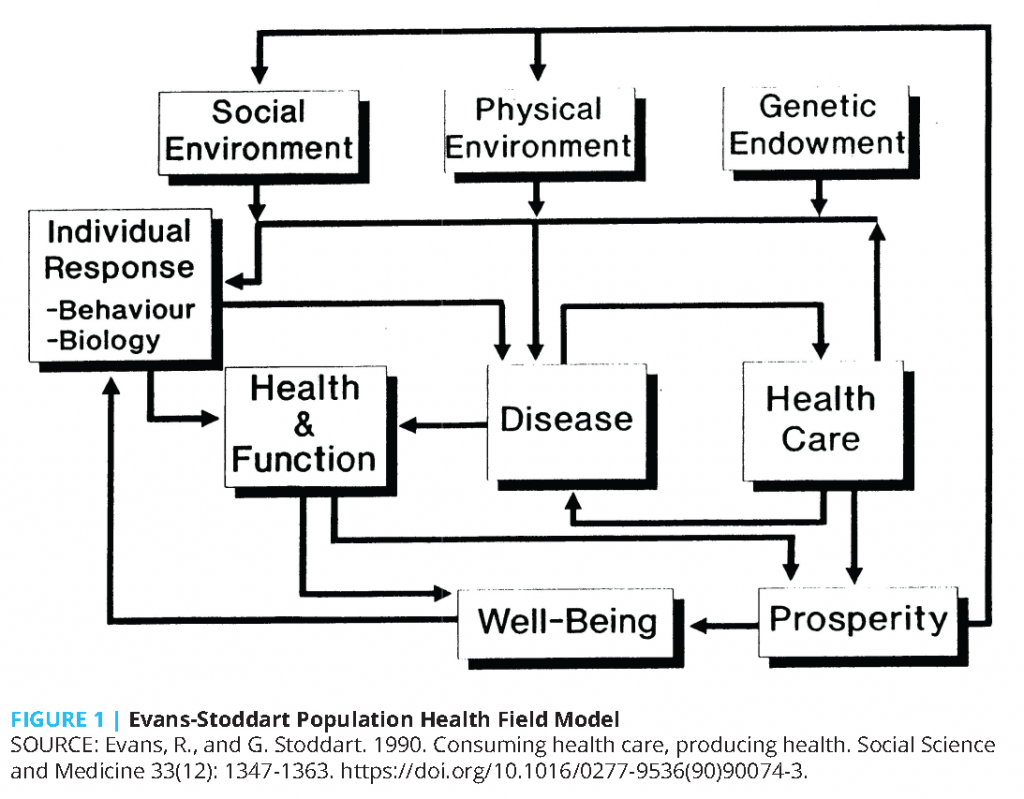

This remains the primary, but still difficult, research and policy question. It derives from the Evans-Stoddart population health field model (see Figure 1), which shows the evolution from the medical model shown in the health care and disease boxes to the broader model with expanded concepts of outcomes and the addition of multiple determinants of health (Kindig, 2007). Stoddart called the model “the fantasy equation,” saying “at present we but vaguely understand the relative magnitude of the coefficients on the independent variables that would inform specific policies rather than broad directions, even if we are beginning to see the variables themselves more clearly” (Stoddart et al., 2006).

The three goals outlined in 1997 were not foolish, but the timing was clearly ambitious. Why was this? The scholarly field of population health is maturing, and those who work in this field are starting to “see the variables more clearly.” In 1997, population health was still a developing field, but today, topics like the social determinants of health roll easily off the tongue of students and policy makers alike. However, progress on Stoddart’s necessary “relative coefficient magnitude” seems slow because of data, analytic methods, limited funding for issues lacking a specific disease label, and the general challenge of establishing causality in social science. However, without these coefficients, concrete answers are lacking. For example, how much should be invested in education in contrast to housing, in job development, or in a minimum household income to ensure that overall health and well-being are improved? Furthermore, within education, what is the magnitude of investments—early childhood versus college or technical school? How do the investments vary for different populations to achieve equity and well-being?

The medical care system continues to exert strong cultural authority to its financial advantage, as Paul Starr astutely predicted decades ago (Starr, 1984). The frustration in not seeing tangible reallocation of medical waste to more health-promoting investments has led some to wonder if such reallocation is a pipe dream and if focusing only on increased social spending would be more realistic (Hughes-Cromwick et al., 2021). Recently, Stoddart (2021) observed: “You can’t rob Peter to pay Paul if Peter is a doctor or other established health care provider. . . . one possibility is to freeze allocations to determinants with low marginal returns, while allocating any new resource increase to determinants with higher marginal returns. Freeze Peter while paying Paul more.”

Research alone does not change policy, but is it possible that not knowing the coefficients is a substantial barrier to making progress in population health? Probably the most important new population health investment under discussion is reducing child poverty. The case can be made that it has received much attention and support because the empirical evidence is strong and respected by many on both sides of the political divide. But even with that evidence, which is lacking for many other social determinants of health, an extension beyond December 2021 was not politically feasible.

So where does that leave these goals? An impossible fantasy challenge? Or a tough problem that will take more time to bear fruit of outcome improvement and disparity reduction? Remaining optimistic, here are what this author believes are new and reasonable goals:

- Advances in methodology and data quality have brought us closer to understanding the fantasy equation and what it tells us about balancing the multiple determinants of health (Kindig and Mullahy, 2022).

- Using this information, set per capita investment benchmarks across determinants, with sharp focus on raising the mean and closing gaps/improving equity (Kindig, 2015a).

- Spend less in wasteful, unneeded health care, and invest more in social determinants, and especially disadvantaged children (Kindig, 2015b).

- Financial formula models like mortgage interest deduction or crop subsidies are devised and implemented to drive these rebalanced investments.

- There are robust multisectoral health outcome trusts or community business model partnerships with adequate core funding to be effective (Kindig, 2016).

- Political and ideological common ground and social solidarity are built to make these five previous points sustainable (Kindig, 2015c).

The last point may seem particularly challenging in these divided times. However, there is promise in embracing “opportunity policies like education and economic development, which produce health and other benefits. Nobel Laureate and economist James Heckman observed that ‘it is a rare public policy initiative that promotes fairness and social justice and, at the same time, promotes productivity in the economy and society at large. Investing in disadvantaged young children is such a policy’. Is there a compelling reason we can’t build coalitions among individuals who embrace competing ideologies to accelerate community well-being and national economic security?“ (Kindig, 2015b).

Given the limitations of my earlier predictions, readers might be legitimately skeptical of these new benchmarks of success, either in their validity or the several-decade timeline toward achievement. However, they are a reasonable challenge to the field of population health, and Nobel Prizes in medicine or economics may await. While the work to be done may seem daunting, I count on population health colleagues to sustain the effort and gauge our progress toward raising overall health and closing unacceptable, inequitable gaps.

Join the conversation!

![]() Tweet this! A new #NAMPerspectives commentary reflects on the last two decades of progress in population health and identifies six critical areas of focus for the next 20 years: https://doi.org/10.31478/202203a #pophealthrt

Tweet this! A new #NAMPerspectives commentary reflects on the last two decades of progress in population health and identifies six critical areas of focus for the next 20 years: https://doi.org/10.31478/202203a #pophealthrt

![]() Tweet this! “Research alone does not change policy”, but a new #NAMPerspectives commentary argues that research in population health specifically can help the field progress in the next 20 years: https://doi.org/10.31478/202203a #pophealthrt

Tweet this! “Research alone does not change policy”, but a new #NAMPerspectives commentary argues that research in population health specifically can help the field progress in the next 20 years: https://doi.org/10.31478/202203a #pophealthrt

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 2022. CMS Releases 2023 Medicare Advantage and Part D Advance Notice. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-releases-2023-medicare-advantage-and-part-d-advance-notice (accessed February 7, 2022).

- Evans, R., and G. Stoddart. 1990. Consuming health care, producing health. Social Science and Medicine 33(12):1347-1363. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(90)90074-3.

- Heckman, J. 2006. Catch ’em young. Wall Street Journal, January 10. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/articles/SB113686119611542381 (accessed February 7, 2022).

- Hughes-Cromwick, P., D. Kindig, S. Magnan, M. Gourevitch, and S. Teutsch. 2021. The Reallocationists Versus The Direct Allocationists. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210729.55316/full/.

- Kindig, D. 2016. To Launch And Sustain Local Health Outcome Trusts, Focus On ‘Backbone’ Resources. Health Affairs Blog, February 10. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20160210.053102/full/.

- Kindig, D. 2015a. From Health Determinant Benchmarks to Health Investment Benchmarks. Preventing Chronic Disease 12:150010. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.150010.

- Kindig, D. 2015b. Improving Our Children’s Health Is an Investment Priority. Milbank Quarterly 93(2):255–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12120.

- Kindig, D. 2015c. Can There Be Political Common Ground for Improving Population Health? Milbank Quarterly 93(1):24-27. Available at: https://www.milbank.org/quarterly/articles/can-there-be-political-common-ground-for-improving-population-health/ (accessed February 7, 2022).

- Kindig, D., and J. Mullahy. 2022 Can the Population Health “Fantasy Equation” Be Solved? Does It Need To Be? Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20220301.585301.

- Kindig, D., J. Nobles, and M. Zidan. 2018. Meeting the Institute of Medicine’s 2030 US Life Expectancy Target. American Journal of Public Health 108(1):87-92. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5719677/ (accessed February 7, 2022).

- Kindig, D., and G. Isham. 2014. Population Health Improvement: A Community Health Business Model That Engages Partners in All Sectors. Frontiers in Health Services Management 30(4):3-20. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25671991/(accessed February 7, 2022).

- Kindig, D. A. 2007. Understanding Population Health Terminology. Milbank Quarterly 85(1):139-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00479.x.

- Kindig, D. A. 1997. Purchasing Population Health: Paying for Results. University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI.

- Magnan, S. 2021. Social Determinants of Health 201 for Health Care: Plan, Do, Study, Act. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/202106c.

- Magnan, S. J., and D. A. Kindig. 2019. Purchasing Population Health—Revisited. Population Health Management 22(2):91-92. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2018.0043.

- McCullough, J. M., M. Speer, S. Magnan, J. E. Fielding, D. Kindig, and S. M. Teutsch. 2020. Meeting the Institute of Medicine’s 2030 US Per Capita Clinical Care Spending Target. American Journal of Public Health 110(12):1735-1740. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305793.

- Starr, P. 1984. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. Basic Books.

- Stoddart, G. 2021. Personal communication with the author.

- Stoddart, G. L., J. D. Eyles, J. N. Lavis, and P. C. Chaulk. 2006. Reallocating Resources across Public Sectors to Improve Population Health, in Healthier Societies: From Analysis to Action, S. J. Heymann, C. Hertzman, M. Barer, and R. G. Evans, editors. Oxford: Oxford University Press.