Sixth Annual DC Public Health Case Challenge - Reducing Disparities in Cancer and Chronic Disease: Preventing Tobacco Use in African American Adolescents

In October 2018, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) and the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) held the sixth annual District of Columbia (DC) Public Health Case Challenge, which was both inspired by and modeled on the Emory University Global Health Case Competition [this perspective summarizing the 2018 event encountered unexpected delays before publication in 2022.]

The DC Public Health Case Challenge aims to promote interdisciplinary, problem-based learning in public health and to foster engagement with local universities and their surrounding communities. The Case Challenge brings together graduate and undergraduate students from multiple disciplines and universities to promote awareness of and develop innovative solutions for twenty-first-century public health challenges experienced by the DC community.

Each year, the organizers and a student case-writing team develop a case based on a topic that is relevant to the DC area and that has broader national and, in some cases, global resonance. Content experts are recruited as volunteer reviewers of the case. Universities located in the Washington, DC, area are invited to form teams of three to six students, all of whom must be enrolled in undergraduate or graduate degree programs. To promote public health dialogue among various disciplines, the competition requires each team to include representation from at least three different schools, programs, or majors.

Two weeks before the Case Challenge event, the case is released and teams are charged to employ critical analysis, thoughtful action, and interdisciplinary collaboration to develop a solution to the problem presented in the case. On the day of the competition, teams present their proposed solutions to a panel of judges, composed of representatives from DC organizations and other subject matter experts from disciplines relevant to the case. The prize categories vary by year but generally include a grand prize as well as awards for the practicality and interdisciplinary nature of the solution. In 2018 a wildcard prize was also awarded.

2018 Case: Reducing Disparities in Cancer and Chronic Disease – Preventing Tobacco Use in African American Adolescents

The 2018 case focused on reducing disparities in cancer and chronic disease through preventing tobacco use in African American adolescents. The case asked the student teams to develop a program that, with a fictitious grant of $2.5 million over five years, would prevent or mitigate the negative effects of tobacco use on adolescents in DC. Each proposed solution was expected to outline a rationale, an intervention, an implementation plan, a budget, and an evaluation plan.

The case framed the issue through three fictional scenarios that drew from circumstances faced by DC residents, with an emphasis on DC’s most vulnerable groups and health equity.

The first scenario described a 17-year-old African American male resident of Ward 8 who is frequently exposed to cigarette and other tobacco product marketing at the small convenience/corner and liquor stores his family often shops at (his family has limited access to grocery stores as do many residents of Ward 8). Although his high school requires a health exam each year, he has irregular interactions with health care providers otherwise, and despite having asthma and knowing the potential risks, he begins smoking. The second scenario presented a 14-year-old high school freshman who, despite the legal age for electronic cigarette use being 18 years old, has tried electronic cigarettes and intends to buy himself one once he has saved enough money. Many of his friends smoke electronic cigarettes, and he is often exposed to secondhand smoke from relatives who smoke cigarettes. The third scenario described a female lifelong resident of Ward 7 who grew up in housing that allowed indoor smoking. She began smoking at 16 years old and continues to smoke at 65 years old, with no success the multiple times she has tried to quit. She has been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, high blood pressure, and, most recently, lung cancer. Her treatment has been delayed because her lack of reliable access to transportation to and from doctors appointments has caused her to miss several appointments. Her grandchildren live with her and are exposed to secondhand cigarette smoke.

The teams were provided with background information on the social-ecological framework; demographics and relevant health disparities in DC; lung cancer, other cancers, and other diseases and conditions associated with tobacco use; causes of health care disparities, including those related to insurance, access to health care services, health education and literacy, and implicit bias among health care workers; behavioral factors including substance use and media influence, school-based interventions, and technology access and impact; tobacco policy and marketing, including national and DC legislation; environmental exposure to tobacco in schools, workplaces, and housing; electronic nicotine delivery systems; community and nonprofit work; trust and cultural competency when working with communities; and unintended consequences of policies.

Team Case Solutions

The following brief synopses, prepared by students from the seven teams that participated in the 2018 Case Challenge, describe how teams identified a specific need in the topic area, how they formulated a solution to intervene, and how they would implement their solution if they were granted the fictitious $2.5 million allotted to the winning proposal. Team summaries are provided in alphabetical order. Several of the solutions mention the need to remove, or mechanisms for removing, e-cigarette flavors because, at the time of the event, the DC law banning such flavors was not yet in place.

The 2018 Grand Prize winner was the team from the University of Maryland, Baltimore. In addition, three additional prizes were awarded: the Harrison C. Spencer Interprofessional Prizes to the team from the Uniformed Services University, the Practicality Prize to the team from the George Washington University, and the Wildcard Prize to the team from the U.S. Naval Academy.

American University: Wellness Labs

Team members/summary prepared by: Ben Szulanczyk, Elizabeth Pham, Elizabeth Taormina, and Ikwo Frank

Background and Statement of Need

Individuals who use tobacco have a higher risk for adverse health outcomes such as cardiovascular issues and cancers (HHS, 2014). In Washington, DC, African American adolescents have an increased likelihood of using tobacco products due to the lack of access to health care services and resources such as health education (Chandra et al., 2009). Romano et al. (1991) found that African American adults who reported having higher stress levels were more likely to smoke than individuals who reported having less stress (Romano et al., 1991). In addition, stress due to living in a high-poverty neighborhood may contribute to high-risk smoking behaviors in African American populations (Chandra et al., 2009), and cigarettes are known to be used to help individuals relieve stress (Epstein et al., 2007).

Intervention

Mindfulness-based activities are newly emerging in the literature as an efficacious intervention for preventing a variety of negative behaviors by reducing external stressors, promoting and enhancing feelings of self-worth, and encouraging accountability and ownership. For example, Tang et al. (2013) tested meditation training on individuals interested in general stress reduction and found a signifi cant decrease in the number of smokers at the end of the intervention; they also found that teaching meditation improved self-control capacity in participants.

In addition, an activity not commonly seen in urban settings is gardening; yet, evidence suggests there are many health benefits of taking care of plants and interacting with nature. In a meta-analysis reviewing the health benefits of gardening, researchers found decreases in stress and increases in quality of life (Soga et al., 2017). Not only does gardening foster practical skills, but it is also an interactive way to practice mindfulness.

Wellness Labs is a multilevel intervention, grounded in the socioecological model, that aims to educate adolescents on healthy coping behaviors for stress and decrease smoking rates among adolescents in Wards 7 and 8. Wellness Labs is based on the relationship between stress and smoking as a coping behavior, and the goal of the organization is to provide a safe space and promote a healthier environment for adolescents living in Wards 7 and 8 in Washington, DC. As an after-school program, Wellness Labs ensures that adolescents ages 11 to 19 in Wards 7 and 8 have the opportunity to learn healthy coping behaviors, such as gardening and practicing mindfulness, with the goal of creating a safe space for students at these urban schools. Wellness Labs’ curriculum focuses on teaching students and family members healthier options to cope with stressors brought upon by urban living environments. The organization aims to enhance middle and high school students’ physical, emotional, and intellectual well-being through its after-school program focusing on drug abuse prevention by educating students, increasing students’ academic achievement, and bringing a sense of community into Wards 7 and 8.

Potential Barriers

Barriers include potential conflicts with other afterschool programs using the same after-school space and time, limited space in schools, and lack of time for students to attend after-school meetings and events. Although students may be busy, there are benefits to enrolling in Wellness Labs. This program allows students to learn how to cope with stressors, take on leadership roles in their school’s community, and make a difference in enhancing their existing school environment to create a safer space.

Georgetown University: A.S.P.I.R.E. (Advocating Substance Prevention in Rising Entrepreneurs)

Team members: Allison Doyle, Christine Hill, Caroline King, Noah Martin, Timothy Putnam, Emily Shaffer

Summary prepared by: Caroline King, Allison Doyle, Emily Shaffer, Christine Hill, Tim Putnam, Noah Martin, Rachel Bailey, Alex Akman

Goal

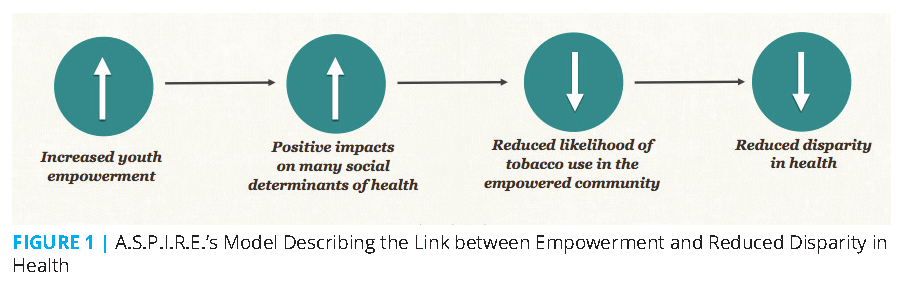

By integrating a project-based learning curriculum, convening community partners, and organizing advocacy efforts to foster youth empowerment in Wards 7 and 8, A.S.P.I.R.E. seeks to reduce racial disparities in health (see Figure 1). A.S.P.I.R.E. has outlined three main goals: informed policy action, curricular infusion, and convening.

Target Population

Throughout the pilot phase, A.S.P.I.R.E.’s staff plans to work with Thurgood Marshall Academy, a public charter high school, and Anacostia High School. In particular, the staff plans to work with 12 teachers from the two schools, each teaching a class of approximately 20 students.

Intended Outcomes

A.S.P.I.R.E.’s approach focuses on care for the advocate and creating solutions to problems that disproportionately affect students, making sure to build coping skills and resilience along the way. The intended outcome is that students not only create specific interventions in their community to solve problems relevant to their own lives but that they emerge from the program with tools that will empower them to resist engaging in negative health behaviors and skills to carry them through successfully to higher education.

Intervention

Curricular infusion: A.S.P.I.R.E.’s curricular infusion model is a problem-based learning curriculum taught by a cohort of teachers (see Figure 2). The intention behind the model is to provide students with a problem-based curriculum that allows them to work on a “real-world” issue in the context of their coursework. The curriculum is structured in partnership with a group of teachers, with three primary sections: self-care, survey, and response. The three phases bring students into contact with a specific problem and allow them the time and opportunity to engage with the issue in a realistic setting while supporting recognition of the importance of self-care.

In addition to the student-centered model described above, the program is structured to support the cohort of teachers in their curriculum development and align the program curriculum with teacher responsibilities such as adhering to common core standards.

Informed policy action: The policy arm of A.S.P.I.R.E.’s model enlists individuals who have demonstrated an active role in their community to participate in a fellowship funded by a grant from the organization. The fellowship is a year-long program in which fellows work closely with a community organizer, hired as a staff member of the organization, to develop tools and skills in pursuing policy and social change around issues they have identified as being critical in their community.

Convening: The convening phase of the model is meant to give depth to projects that students wish to continue through a network of students’ clients, such as Up Top Acres (https://www.uptopacres.com/), which operates a network of rooftop farms across the DC metro area, as well as resource-providing clients, such as DC public libraries. The network developed during this convening phase allows students to further develop the projects that were originated in their courses and to facilitate potential civic engagement outcomes in the community.

Potential Barriers and Responses

Foreseeable potential barriers include establishing school buy-in, adequate faculty support, and project sustainability. To help overcome these barriers, the organization allocates space to support teachers at partnering high schools. Support also includes monetary compensation and assistance to staff for curriculum development.

Howard University: REEvival

Team members/summary prepared by: Ngozi Elobuike, Emanuel Demissie, Calie Edmond, Kimberly Vilmenay, Tisa Thomas, and Maya Rashad

Background/Statement of Need

Cancer and chronic diseases disproportionately affect some communities of color, with smoking as one of the primary risk factors (ALA, 2019; Siegel et al., 2015). Using an evidence-based approach, REEvival aims to uncover methods of marketing and social influences that increase youth tobacco use. The program also addresses how the lack of accessible options for healthy food drives families toward retail locations with heavy tobacco advertising.

Goal

The REEvival initiative is based on the tenets of resisting the negative influence of harmful tobacco advertising, engaging the community around issues of tobacco use and food insecurity, and empowering youth in the community to engage in visual arts as an activism tool to counteract the imagery and harmful messaging of tobacco companies. REEvival aims to achieve this goal through the development of a tobacco resistance hub. In this physical space, youth and other community members have access to educational tools, including a series of awareness-raising and social resistance workshops and a program to learn art techniques to be applied in a PhotoVoice (https://photovoice.org/) counter-marketing endeavor. Additionally, REEvival aims to address food insecurity in the area by partnering with and buying fresh produce from local farmers’ markets corner stores can then sell for a fraction of the cost. Moreover, corner stores are incentivized to display PhotoVoice images in exchange for receiving profits from the sale of the fresh produce.

Intended Outcomes

One of the primary intended outcomes for each cohort of REEvival is an overall increased awareness of predatory advertising techniques used by tobacco companies in African American neighborhoods. In addition to becoming more knowledgeable of such subtle marketing techniques, youth will also learn the historic detriments that prolonged tobacco use has had on the health of their communities. This includes becoming aware of the health disparities experienced by African Americans in comparison to White residents, including mortality rates from chronic diseases such as lung cancer and COPD.

After acquiring a solid foundation of knowledge, youth undergo supplemental training in the tobacco resistance hub, where their self-efficacy to refuse and resist tobacco use is strengthened. The inclusion of real-world role-playing scenarios in this training aims to build each participant’s capacity to improve their ability to resist when exposed to similar pressures at school and their home environments.

The intended outcome for the youth’s PhotoVoice project is to have each participant discover their power to influence their environment through creative means. The PhotoVoice project also aims to instill a greater sense of activism within the cohort that propels them to continue resisting tobacco advertising long after their time in the program ends. In addition, each PhotoVoice project will be displayed in an art gala at which families, REEvival staff, local government officials, and other residents can appreciate each participant’s work. Art show attendees will have the option of purchasing the PhotoVoice images to provide financial assistance to REEvival and the student creators and encourage the latter to continue their unique forms of resistance to foster a sustainable, long-term cycle of change.

Intervention

An important aspect of the intervention includes addressing tobacco advertising directed at African American communities in Wards 7 and 8. Historically, aggressive marketing techniques have promoted flavored products (e.g., menthol cigarettes) and misused cultural symbols to increase tobacco sales in African American communities. At REEvival’s resistance hub, youth will have access to educational resources on resisting marketing tactics and have the opportunity to document and counter such advertising through PhotoVoice. The PhotoVoice project will serve as a community-based participatory research tool and a creative endeavor that allows youth to share their perspective on how tobacco has affected their communities.

Strategy/mechanism/details: REEvival is based on the social influence resistance model, a form of intervention proven effective in reducing tobacco use among youth (Lantz et al., 2000). The model has been means-tested against other methods, and literature shows it to be an effective approach for reducing youth tobacco use (SAMHSA, n.d.; Sherman and Primack, 2009; Sussman et al., 1993a; Sussman et al., 1993b). The model strengthens communication, decision-making, and assertiveness skills of youth and adolescents by focusing on building skills to recognize and resist strategic tobacco marketing.

Potential partners: REEvival aims to partner with the Benning Park Community Center, corner stores in Wards 7 and 8, and AmeriCorps. The program will also partner with local primary care sites in DC to display images from the PhotoVoice project.

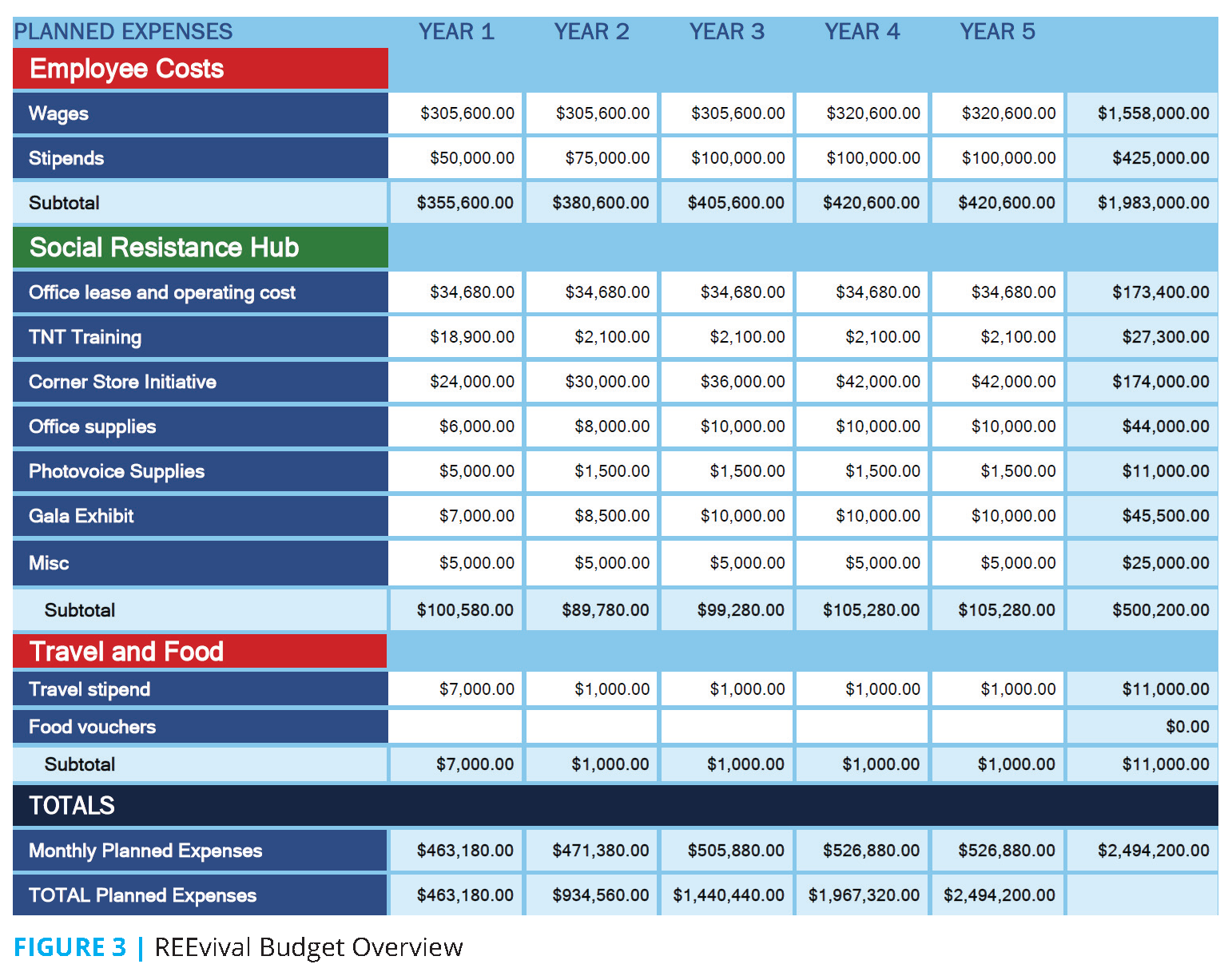

Brief budget overview: A brief overview of REEvival’s budget is shown in Figure 3.

Potential barriers and responses: A potential barrier to the program’s success is that it is dependent on recruitment of students to participate in the curriculum held at the resistance hub. Students will be recruited via fliers posted at Ward 7 and 8 high schools, with participants offered a monthly stipend for their participation. An additional barrier is acquiring buy-in from local corner stores to display PhotoVoice anti-tobacco imagery in their stores. REEvival plans to overcome this potential barrier by supplying fresh produce to corner stores in exchange for their participation and allowing them to keep any profits from the sales of the produce.

Conclusion

REEvival focuses on decreasing the prevalence of smoking in African American adolescents in Wards 7 and 8 by providing tools to resist marketing ploys targeted at youth, empowering youth to have a voice through the PhotoVoice component, and engaging in and improving their communities by changing the role the corner store plays in communities. Art has played an important role in DC’s history, and the importance of art in African American communities, in particular, prompted REEvival to include the PhotoVoice component in its programming. One of the program’s main challenges is introducing healthier options in corner stores and leveraging existing policies already implemented by the DC government.

The George Washington University: Project Adolescents Resisting Tobacco and Partnering Alongside Communities (ART PAC)

Team members: Melissa Aune, Hallie Fox, An Harmanli, and Anastasia Kanakaris

Summary prepared by: Hallie Fox, Melissa Aune, and An Harmanali

Statement of Need

In Washington, DC, lung cancer incidence and mortality rates due to tobacco use are significantly higher among African Americans than Whites (Garner et al., 2013). Tobacco use that begins during youth and young adulthood is largely preventable, but youth living in Wards 7 and 8 are more likely to smoke and use tobacco (GU, 2016). Smoking behaviors have been linked to socioeconomic disparities (CDC, n.d.), and youth in Wards 7 and 8 could benefit from a multitiered approach to reduce these disparities and address social-ecological factors that contribute to youth tobacco use and community health outcomes.

Overview of Intervention

The goal of ART PAC is to reduce the incidence of smoking among African American adolescents in Wards 7 and 8 by leveraging existing strengths and practices within these communities. In response to this challenge, Adolescents Resisting Tobacco and Partnering Alongside Communities (ART PAC) is a multitiered intervention that incorporates youth arts-based education and social skills training, promotes youth advocacy development, connects families with community organizations, and considers critical policy changes at the local level. This program is not about “fixing” broken communities or helping “high-risk” youth; rather, it is about empowering youth across Wards 7 and 8 to be leaders in their communities and resist tobacco use.

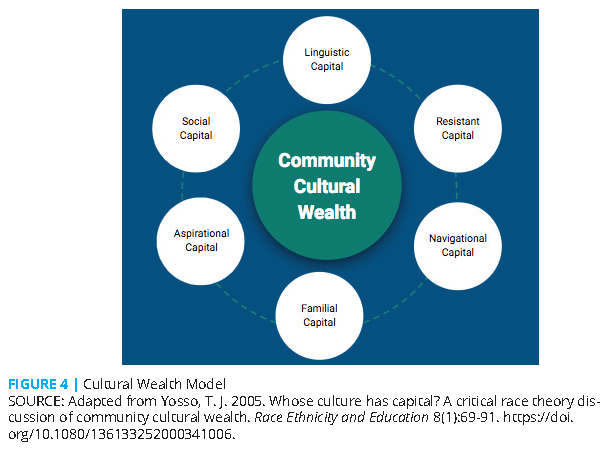

Underlying theory: ART PAC is a strengths-based approach grounded in the community cultural wealth model (see Figure 4). This critically informed model challenges traditional interpretations of cultural capital and shifts a deficit view of communities of color toward one that acknowledges the multiple strengths in these communities (Yosso, 2005). Thus, high-risk communities are not solely places with problems to solve but rather culturally rich communities with existing strengths to leverage.

Intervention

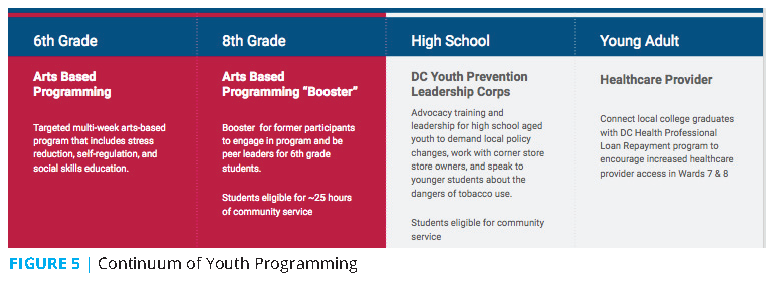

Youth programming: ART PAC is designed to help youth develop effective stress reduction and coping skills, encourage healthy behaviors, and foster community involvement. Direct programming begins in sixth grade and continues with opportunities for eighth-graders to be near-peer mentors. High school students are encouraged to participate in the DC Youth Prevention Leadership Corps (https://drugfreeyouthdc.com/about/), an existing organization that trains youth to be advocates and leaders against drug use in their community (Drug Free Youth DC, n.d.). ART PAC also encourages more young people to enter health care professions and work in their communities by familiarizing local college graduates with the DC Health Professional Loan Repayment Program (DC DOH, n.d.). ART PAC provides a continuum of support from late childhood through high school and into young adulthood (see Figure 5).

Family outreach: Research has shown that parents have a significant impact on whether or not adolescents choose to smoke (Hill et al., 2005); thus, the interpersonal prong of the ART PAC program aims to involve parents in adolescent tobacco prevention, reduce adult smoking and secondhand smoke exposure in the home, and facilitate increased tobacco counseling for patients by health care providers. Families of all sixth-grade students in Wards 7 and 8 will have access to an at-home curriculum that encourages communication and skill-building between teens and parents (Bauman et al., 2001). ART PAC will also connect parents and caregivers with free tobacco cessation classes offered by Breathe DC throughout the District (Breathe DC, n.d.). Additionally, health care providers will be trained to use the CEASE (Clinical Effort Against Secondhand Smoke Exposure) curriculum, which is free for clinicians and families, to assess parental smoking and provide cessation resources at pediatric visits (Massachusetts General Hospital, n.d.; Winickoff et al., 2012). This will be accomplished in partnership with local universities

to provide financial incentives to providers using the CEASE model and to support cultural competency training for medical students.

Community engagement: ART PAC leverages the strengths of health programs and leaders in Wards 7 and 8 who are already working to prevent and reduce tobacco use. By leveraging partnerships with these community health champions, ART PAC brings awareness to tobacco industry marketing tactics and the effect of corner store advertising and product placement. The youth ART PAC program will culminate with an Art and Health Fair to showcase student work and celebrate the strengths and creative talents of youth in the community while promoting health services.

Adolescents exposed to convenience store settings with a tobacco power wall (a visible wall of tobacco products with attractive advertising and discounts often at point of sale) report being more willing to use e-cigarettes in the future compared to adolescents exposed to a setting in which the power wall was hidden (Li et al., 2013). For this reason, ART PAC encourages Ward 7 and 8 corner store owners to decrease tobacco advertising and visibility of the tobacco power wall. Additionally, ART PAC will connect store owners with the DC Central Kitchen Healthy Corners program, which provides incentives such as wholesale pricing, marketing support, technical assistance, and logistical support to corner store owners who increase the healthy foods available for purchase in their stores (DC Central Kitchen, n.d.). Through these measures, ART PAC aims to not only reduce the power of tobacco advertising and the

tobacco power wall, but also increase community access to fresh and healthy foods.

Policy solutions: ART PAC interventions include advocating for policy recommendations that will (1) change the advertising environment for youth in Wards 7 and 8, (2) make it harder for youth to purchase tobacco products and e-cigarettes, and (3) concurrently encourage health-supportive behaviors. It is also essential for DC to pass regulations that ban flavor in e-cigarettes, which has been shown to attract first-time youth smokers and hold overall appeal to underage smokers (Villanti et al., 2017). ART PAC will also advocate for one hour of tobacco prevention continuing education as a mandatory requirement of health professional license renewal in the District. In addition, research has shown that food insecurity has been associated with smoking (Hosler and Michaels, 2017). To reduce the stress of food insecurity and the requisite association with smoking, ART PAC recommends increased funding of the Produce Rx program and Healthy Corners program to immediately improve food access for community residents.

Brief budget overview: A majority of ART PAC’s budget will be allocated to three full-time community outreach coordinators. Additional funding will support youth programming and family materials, including at-home curriculum and volunteer incentives.

Participant engagement and program sustainability: One of the biggest challenges of youth and community programming is engagement and retention of participants. ART PAC will provide several incentives to encourage involvement and reward students for continuing with the program over time. Family and community volunteer incentives will be provided in collaboration with community members. Additionally, it is critical to monitor program impact and ensure program sustainability through ongoing progress monitoring and evaluation. ART PAC will transition the community and family outreach functions to partner organizations at the end of five years to support sustainability. Advocating for critical policy changes within the District will ensure lasting structural shifts in Wards 7 and 8, which will likely sustain the gains of ART PAC and reduce tobacco use among African American adolescents

for years to come.

Uniformed Services University: CEASE

Team members/summary prepared by: LCDR Shawna Grover, Maj Tonya Spencer, LT Breda Jenkins, Guzal Khayrullina, ENS Michelle Mandeville, 2LT Vidya Lala

Statement of Need

The rate of cigarette smoking in the United States has steadily declined in recent years, in part due to smoke-free laws enacted in recognition that smoking contributes to increased risk of morbidity and mortality, including lung cancer (Wang et al., 2018). Despite this downward trend, Wards 7 and 8 have the highest smoking rates in DC at 15 and 23.6 percent, respectively (Garner et al., 2013), surpassing the national average of 13.1 percent for the 18- to 25-year-old age group (Jamal et al., 2018). Furthermore, approximately a quarter to a third of the population of these wards are adolescents (Chandra et al., 2013), highlighting a particularly worrisome problem because of the historically high prevalence of smoking initiation in this age group.

Goal

The mission of CEASE, to promote smoke-free environments, is driven by four goals: (1) empower individuals to make informed decisions about their lifestyle and health, (2) facilitate collaboration between communities and state organizations, (3) empower communities to advocate for policies and laws that support a smokeless environment, and (4) measure the impact of prevention activities through collection of health outcomes and smoking data.

Intended Outcomes

The intended outcome of the CEASE program is to reduce smoking rates in Wards 7 and 8 through a multifaceted community partnership program. The initiative proposes to establish youth mentorship; host public health fairs to assess mental health needs and provide alternatives to smoking; use social media to raise awareness of the health implications of smoking; and advocate for policy change at the local, state, and national levels.

Intervention

Target population: The purpose of CEASE is to affect the smoking behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs of African American adolescents between the ages of 10 to 19 living in Ward 7 and 8. Influencing these individuals is accomplished directly by engaging with them and indirectly through interfacing with their support structures, including their families, schoolteachers, church leaders, and other community members.

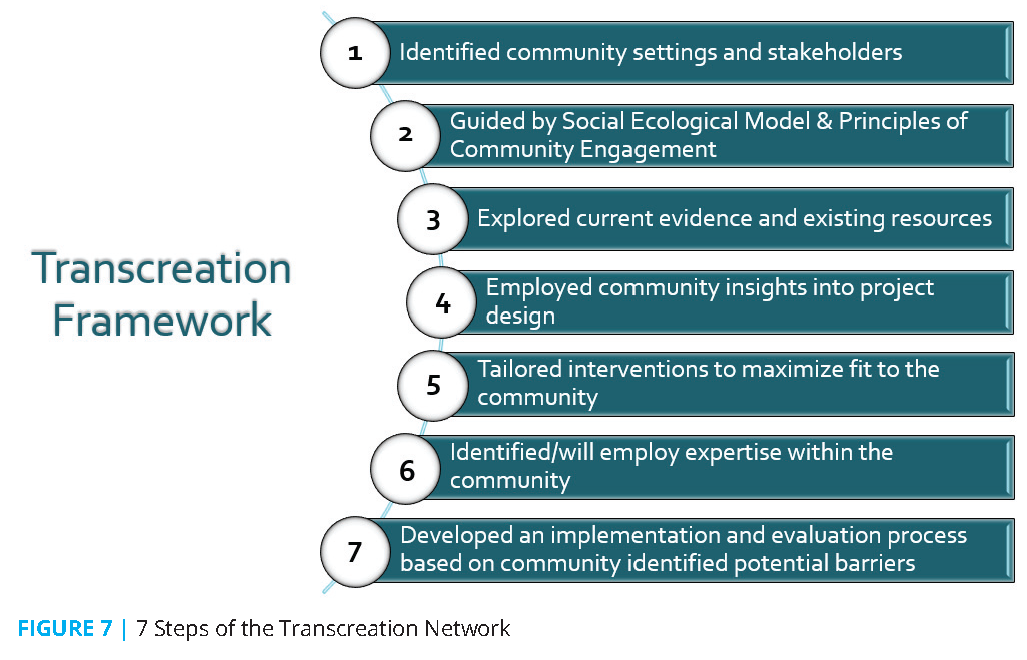

Underlying theory: The transcreation framework is the foundation of the CEASE program (see Figure 7). The framework consists of seven steps related to the design, delivery, and evaluation of community behavioral interventions to decrease health disparities (Nápoles and Stewart, 2018). Each step of the framework has been tailored to accomplish CEASE’s mission.

First, visits to Wards 7 and 8 were arranged to personally converse with residents, particularly young people and community leaders, to better understand the problem of adolescent smoking from their perspectives. Second, the social-ecological model and principles of community engagement theories were selected to provide structure for developing the CEASE program (NIH, 2011). In addition to incorporating the principles of these theories, the CEASE program builds on current evidence, existing resources, and community insights to design interventions that aim to maximize community involvement and respond to the needs of Wards 7 and 8 residents.

Significant consideration of the resources and challenges within the community was necessary to identify and address potential barriers to the program’s success. A critical component of the CEASE program is the role of the community liaison, which capitalizes on community expertise and accounts for the community’s mistrust of perceived “outsiders.” Finally, an implementation and evaluation process was developed with community leaders and the liaison to ensure the program effectively addresses the community’s needs and concerns regarding the community-entrenched problem of adolescent smoking.

Strategy: The CEASE program proposes to interface with community leaders and other influences, such as schools, churches, and community associations, through a community liaison tasked with coordinating the following interventions:

- Initiate a school-based program where high school students develop and teach a smoking prevention curriculum to elementary and middle school students during their health classes, as peer-led smoking prevention programs are not only more effective than traditional teacher-led programs, but they also instill the anti-smoking message in the mentors while providing mentorship to the younger students (Flay, 2009).

- Build community health fairs to encourage tobacco prevention and cessation through educational and health screening booths, curtail boredom through alternative social activities, and reduce stress through mental health screening and mindfulness exercises.

- Develop a community-led media campaign to display graphic images of the negative effects of tobacco use in a manner that reflects the community’s demographics and maintains cultural sensitivity.

- Advocate for new policies or policy changes through collaboration with local, state, and national organizations.

Potential partners: The success of CEASE depends on partnerships formed with Ballou High School, Congress Heights Recreation Center, and Rehoboth Baptist Church. Further collaboration with Breathe DC, Youth in Mind Inc., DC Tobacco Free Coalition, Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, and the American Cancer Society is essential for policy change.

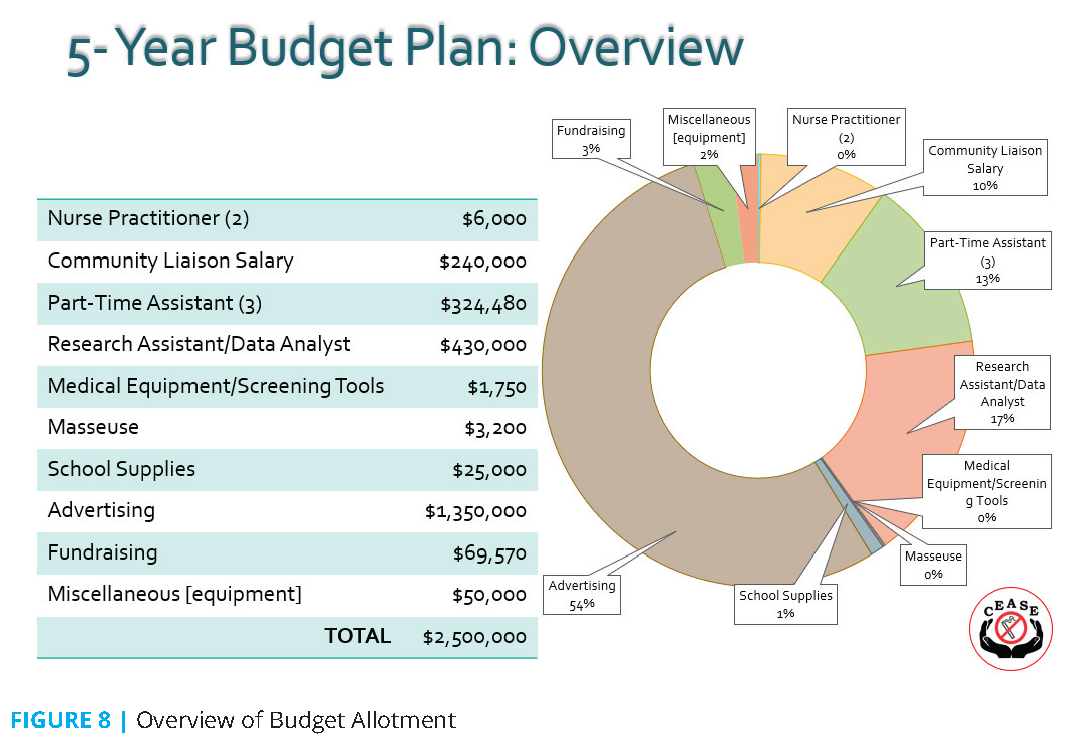

Budget: The budget overview in Figure 8 shows a large allocation of funds toward advertising due to strong emphasis on leveraging community programs as a foundation for engagement through enhancement of existing events. Furthermore, program evaluations will be conducted regularly to determine possible redistribution of funds and fundraising events, such as sales from community-authored cookbooks, which will provide financial support beyond the initial five-year projected budget.

Potential Barriers and Responses

During the initial visit to Ward 8, several individuals expressed distrust about the imposition of outsider values on their community. Respecting community members’ concerns with perceived “outsiders” and their strong emphasis on maintaining their established cultural values, CEASE plans to hire a liaison from within the community chosen by community members to oversee program interventions.

Sustainability

The transcreation framework provides a community-oriented approach to promote sustainability. An alliance with community leaders will enable the community to take ownership of the CEASE program and build on existing community programs, strengths, values, and culture. In this way, the CEASE program’s multifaceted, theoretical approach has great potential to be sustained.

U.S. Naval Academy: RiseDC

Team members/summary prepared by: Eric Cal, Garrett Forrester, George Gilliam, Paige Miles, Alexander Murray, and Kayla Olsen

Statement of Need

Nicotine and tobacco use, especially among adolescents, affects Wards 7 and 8 at far higher levels than other wards in DC and nationwide. Limited access to health care, higher rates of poverty, and greater disparities in public education are contributing factors to the issue of adolescent smoking.

Goal

The purpose of RiseDC is to reduce youth nicotine and tobacco use in Wards 7 and 8 of DC. The long-term goals of RiseDC are to empower the community to break the generational cycle of nicotine and tobacco use, empower students to rise above the difficulties they encounter in their everyday lives, and improve community health through outreach programs and improved standards of health care.

Intended Outcome

RiseDC uses a three-pronged approach consisting of a school mentoring program, a prenatal and postnatal SMS texting program, and a targeted social media advertising campaign. The mentorship program provides healthy role models from the community for elementary and middle school-aged students. Through community involvement and daily text messaging reminders to mothers about the dangers of tobacco use in a home with young children, the SMS texting program aims to reduce tobacco use by expectant mothers and, in turn, break the generational cycle of tobacco and nicotine use. Using community leaders, the social media campaign aims to reduce the popularity of tobacco use among youth and lower nicotine use in area high schools.

Intervention

Target population: The two main target populations for the RiseDC program are adolescents and young mothers within Wards 7 and 8. Within Wards 7 and 8, the majority of residents in these two groups are African American and are at a higher risk for exposure to tobacco and use of nicotine products.

Rationale: RiseDC is founded upon the idea of breaking the cycle of tobacco use within Wards 7 and 8. RiseDC’s teen mentoring program aims to stop teens from trying tobacco products and break existing habits related to tobacco use. Another approach is to create smoke-free households that promote a culture unsupportive of tobacco use. Before a baby is born, many parents experience a willingness to change for the benefit of their future child(ren) that can be used to make the life change of smoking cessation.

Strategy: The three strategies that RiseDC proposes to break the cycle of tobacco use are a teen mentoring program, a social media advertising campaign, and prenatal and postnatal texting programs.

RiseDC will host a school program that spreads awareness about the dangers of tobacco use to target teenagers in Wards 7 and 8. This program pairs older students as mentors with younger students to provide role models, benefiting the students in the style of Big Brothers Big Sisters mentorship that has been proven to be successful. Students are incentivized to participate in the program with small rewards, including a t-shirt day at school instead of their typical uniforms, and larger rewards, including a scholarship for ten students each year.

Outside of schools, RiseDC maintains a website alongside social media campaigns to reach the larger teenage population in Wards 7 and 8. National advertising campaigns that have been tailored to specific populations have been proven to be more effective. To target this population, the advertisements will focus on subjects that matter to teenagers, such as sports and social relationships, and use members from the community to demonstrate that tobacco use can negatively affect an entire community.

RiseDC plans to create an SMS text messaging program for young mothers and teenagers within the teen mentoring program that supports resisting tobacco use. A study in Tennessee showed that women who used a similar program were 15 percent more likely to quit tobacco use. The RiseDC website will include an option to sign up for the text messaging program, which will also be offered to young mothers when they visit local clinics. The subject material of the text messages ranges from facts and statistics about the dangers of tobacco use to moral support for those resisting tobacco use or those trying to quit.

Potential partners: RiseDC relies on continued involvement from the community, particularly in partnering with schools and hospitals to accomplish the desired outreach. Partnering with schools is a necessary component to create the mentoring program. When surveyed by phone about the RiseDC program, more than 75 percent of schools in Ward 7 and 8 showed interest. Hospitals and health care clinics also play an important role in reaching young mothers and encouraging them to sign up for the prenatal care text messaging program.

Potential Barriers and Responses

The success of RiseDC depends on access to technology. The text messaging program and app can only be effective for those with access to mobile phones. However, students without access to mobile phones may participate in RiseDC’s mentorship program, which enables them to overcome this problem with access to an individual trained to share the same information as the text messages. The prenatal text messaging program requires at least one clinic visit, which may not always occur. To alleviate the barrier of health care clinic access, RiseDC plans to encourage women to recommend the app and text messaging program to their family and friends and to use advertisements to increase awareness of the program and its benefits. In the future, RiseDC aims to expand to include a mobile prenatal clinic operating within Wards 7 and 8 to further decrease the barrier to health care that comes with travel time and travel-related costs.

University of Maryland, Baltimore: DC Health Passport Program

Team members/summary prepared by: Jennifer Breau, Mc Millan Ching, Dominique Earland, Chigoziem Oguh, Erin Teigen, and Adrienne Thomas

Statement of Need

In Washington, DC, African American adolescents in Wards 7 and 8 use tobacco products at a higher rate than their White peers in wealthier wards (Price et al., 2013). Disparities in access to health care, education, housing, employment, green spaces, and other resources contribute to the higher rate of tobacco use in African American adolescents in DC. These disparities, combined with tobacco use, are associated with lung cancer mortality in African Americans in DC that is twice the rate of their White, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic peers (Price et al., 2013).

Goal/Intended Outcomes

The goals and objectives of the DC Health Passport Program are to:

- Strengthen community trust and access to health resources in Wards 7 and 8

- Promote agency and advocacy to mitigate health disparities within the community

- Reduce risk factors for cancers in children and families

- Increase number of screenings and resources accessed following the nine-month DC Health Passport Program

- Increase self-perceived ability to advocate for self, community, and society

- Improve participation in health promotion activities

Intervention Description and Underlying Theory

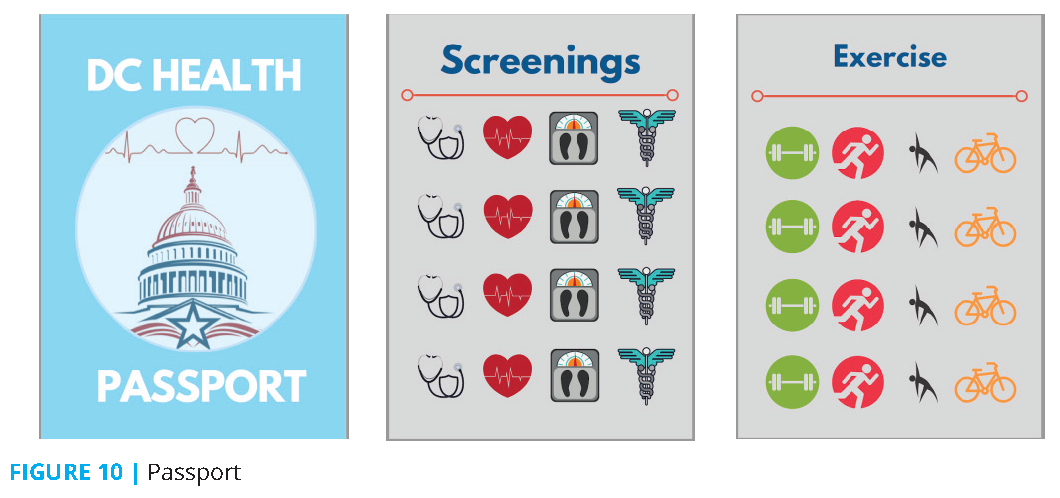

Target population: The DC Health Passport Program begins with 60 seventh- and eighth-grade students and their parents: 30 students from one middle school in Ward 7 and 30 students from one middle school in Ward 8. Students are recruited through partnerships with the middle schools, local community centers, and churches, and they are enrolled in the program for a minimum of two years. Figure 9 illustrates the recreation centers, schools, and churches located in Wards 7 and 8 that the program aims to form partnerships with. Upon enrollment, students and their parents will receive “health passports” that track their progress while enrolled in the program. Each time a student or parent completes a health or advocacy activity, they will receive a stamp. Prizes are awarded as students and parents continue to progress through the program.

Program overview: The DC Health Passport Program follows the social-ecological model (Stokols, 1996), using individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy interventions to empower African American adolescents and their families in Wards 7 and 8. The DC Health Passport Program uses a “passport” (see Figure 10) in which participants receive stamps when they make healthy choices or participate in an advocacy activity. After receiving a certain number of stamps, participants receive one of several rewards, including grocery gift cards, movie tickets, iTunes gift cards, sports memorabilia, and tickets to DC-area sporting events.

Incentive-based programs have been found to increase healthy behaviors and outcomes, such as losing weight or curbing cigarette use (Loewenstein et al., 2013; Volpp et al., 2011). Studies have shown that programs using small, frequent rewards are more successful than programs that use incentives that are less visible (Loewenstein et al., 2013; Volpp et al., 2011). Previous studies have demonstrated that the improved results of incentive-based programs were found even after the program’s rewards concluded (Mitchell et al., 2013).

The DC Health Passport Program continues to engage students who transition to high school through the program’s Student Leader role. Student Leaders mentor middle school participants and aid in the development of policy and advocacy initiatives within the program.

Team sports are an essential part of the DC Health Passport Program. The opportunities to play sports decrease as children get older, and socioeconomically disadvantaged students, in particular, lack the opportunity to participate in sports (Powell et al., 2006). In addition, early engagement in sports increases the likelihood of continued physical activity over the life course (Tammelin et al., 2003). The DC Health Passport Program is designed to encourage adolescents to lead a healthier lifestyle by increasing exercise, decreasing stress, and improving self-esteem through participation in team sports and the arts. Participation in a team sport is associated with a reduced likelihood of smoking and tobacco use (Diehl et al., 2012; Escobedo et al., 1993).

Every other weekend, the local community centers will host a “Community Day” for students and their families. Community Days begin with a large, family-style meal where students, their families, and mentors from local graduate programs build relationships in an informal setting. After the meal, students engage in a PhotoVoice advocacy project while parents meet with community health workers (CHWs), gain access to important community resources, participate in health-related lectures and advocacy workshops, and hear from community leaders and other guest speakers. Cancer risk reduction programming will also be available during these weekend Community Days. The final portion of each Community Day will include basketball games and time for students to meet individually with their graduate mentors.

The PhotoVoice advocacy project is led by interdisciplinary graduate students from Howard University, the George Washington University, and Georgetown University. Each week, students are provided with a camera and given topical “assignments,” ranging from photographing disparities in their environment to capturing images of the harmful impacts of smoking. These bimonthly lessons use a curriculum focused on the social-ecological model to explore individual, community, and societal level predictors that contribute to health disparities in cancer rates. At the end of the eight months, students will develop photo narratives and a map of the photos to present to local government officials and community members at the Anacostia Arts Center.

The PhotoVoice project enables participating youth to describe their perceived needs and affirm the perspective of those most at risk for engaging in tobacco use. Previous studies have shown that PhotoVoice may result in cultivating long-term relationships (Strack et al., 2004). Social support is an established protective factor at the interpersonal level to prevent tobacco use among adolescents (Kim and Chun, 2018). Local officials, stakeholders, interprofessional mentors, and the greater public also learn from participating youth and become partners in reducing health disparities. Students are encouraged to express themselves through their art, which will be collected and displayed at an end-of-year installation open to the greater Washington, DC, community, held at the Anacostia Arts Center.

Before each bimonthly event, interprofessional student mentors participate in a health disparities journal club and use this knowledge to mentor middle school students based on the curriculum. Mentoring will include teaching students about making healthy choices, the importance of education, how to advocate for themselves, and general support. Mentoring focuses on development rather than prescriptive activities, allowing space for mentors and mentees to build a relationship and for mentors to be role models in an organic and meaningful way (Karcher, 2005). Mentors will also teach participants self-advocacy and increase confidence in students’ ability to communicate their needs in the classroom and the larger community.

Policy interventions: In addition to encouraging ongoing discussions between participants and leaders in the community, the DC Health Passport Program will work with students to advocate for better services, more supportive policies, and greater protections in their community. In years one through five, the DC Health Passport Program aims to accomplish the following new policies/changes to current policies:

- Increasing penalties for retailers selling tobacco products to minors

- Banning all discounts on tobacco products

- Banning e-cigarette fl avors

- Banning menthol cigarettes

- Prohibiting collegiate and professional athletes from using tobacco products during athletic events

Student participants will be trained as advocates and work with the DC Health Passport Program director and CHWs to engage area residents, local businesses, colleges and universities, hospitals and health care organizations, and local and national advocacy groups to form a coalition that will drive change in these areas.

Adolescents can be effective self-advocates and create change in their own communities (Winkleby et al., 2004). However, the cultural and institutional barriers that prevent their voices from being heard must be removed before they can advocate (Webb, 2002). Engaging students in community advocacy projects, particularly those focusing on social and environmental change, has significantly reduced regular smoking (Winkleby et al., 2004). The DC Health Passport Program believes this approach will center the community in the advocacy initiative and ensure the message is coming from their collective voice.

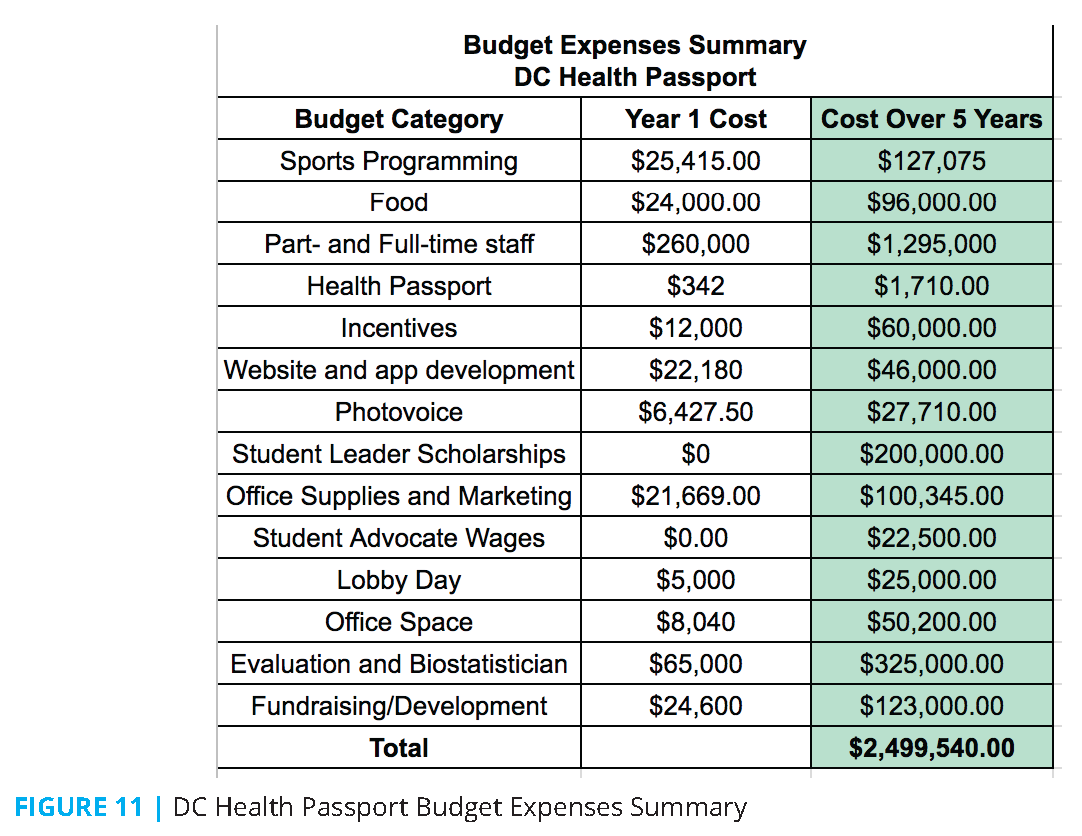

Budget overview: An overview of the DC Health Passport Program’s budget is shown in Figure 11.

Evaluation: In coordination with an institution that has an Institutional Review Board, the DC Health Passport Program will use CBPR to collect and monitor participant health data. The DC Health Passport Program will serve as a tracking log, where research partners monitor health promotion activities and measurable outcomes of those activities at three-, six-, and nine-month intervals. In conjunction with plans for the George Washington University to build a new hospital in Ward 8, the DC Health Passport Program will help develop community trust between residents and professionals.

Conclusion

The DC Health Passport Program engages students through athletics and the arts, encouraging healthy choices and an active lifestyle. Through participation in athletics and the arts, individuals and families are connected with critical resources and are empowered to create their own healthy communities.

Conclusion

The Case Challenge has brought the work of the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies (HMD) to both university students and the DC community. The NAM and the HMD continued this activity with the 2019 DC Public Health Case Challenge, on the topic of “Reducing Health Disparities in Maternal Mortality by Addressing Unmet Health-Related Social Needs” and the 2021 Case Challenge, on the topic of “Addressing Infectious Diseases Using a Population Health Approach: Prevention and Control of Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections in Young Adults 18–24” (the 2020 Case Challenge was canceled due to the ongoing pandemic). The events have been sponsored and cohosted by the HMD Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, with the support of the NAM’s Kellogg Health of the Public Fund and the engagement of related activities of the National Academies, including the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education, the Roundtable on the Promotion of Health Equity, and others. HMD and NAM staff continue to look for new ways to further involve and create partnerships with the next generation of leaders in health care and public health, and the local DC community through the Case Challenge.

To ensure the team solutions consider the complex, but critically important, upstream and multilevel factors that affect health, the Case Challenge organizers will continue to ensure the ecological model (IOM, 2003) and upstream factors are represented in the case document sent to the competing teams in advance of the event. In addition, they will hold the annual webinar before the case is released to the competing teams to provide the teams with a primer on evidence-based policy solutions for public health issues. The webinar will also provide an overview of the Case Challenge, best practices, and a question-and-answer period. The webinar will be recorded so that students have future access to it. The organizers are also exploring ways to further engage the student case-writing team, who are critical to writing the document that sets the stage for the Case Challenge, such as a writing retreat, a webinar, and meetings with local DC officials on the topic they are exploring.

Join the conversation!

Download the graphics below and share them on social media!

References

- American Lung Association (ALA). 2019. Tobacco use in racial and ethnic populations. Available at: https://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/smokingfacts/tobacco-use-racial-and-ethnic.html (accessed March 6, 2019).

- Bauman, K. E., V. A. Foshee, S. T. Ennett, K. Hicks, and M. Pemberton. 2001. Family Matters: A family-directed program designed to prevent adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. Health Promotion Practice 2(1):81-96. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.4.604.

- Breathe DC. n.d. Tobacco cessation services. Available at: https://breathedc.org/bdc-files/BreatheDC_cessation_brochure_web.pdf (accessed December 28, 2018).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). n.d. Cigarette smoking and tobacco use among people of low socioeconomic status. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/disparities/low-ses/index.htm (accessed March 19, 2019).

- Chandra, A., J. C. Blanchard, and T. Rider. 2013. District of Columbia community health needs assessment. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR207.html (accessed January 3, 2022).

- Chandra, A., C. R. Gresenz, J. C. Blanchard, A. E. Cuellar, T. Ruder, A. Y. Chen, and E. M. Gillen. 2009. Health and health care among District of Columbia youth. Arlington, VA: RAND Corporation. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR751.html (accessed January 3, 2022).

- DC Central Kitchen. n.d. Healthy Corners. Available at: https://dccentralkitchen.org/healthy-corners/(accessed December 28, 2018).

- Diehl, K., A. Thiel, S. Zipfel, J. Mayer, D. G. Litaker, and S. Schneider. 2012. How healthy is the behavior of young athletes? A systematic literature review and meta-analyses. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 11(2):201-220. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3737871/ (accessed January 3, 2022).

- District of Columbia Department of Health (DC DOH). n.d. DC Health Professional Loan Repayment Program – HPLRP. Available at: https://dchealth.dc.gov/service/dc-health-professional-loan-repayment-program-hplrp (accessed December 28, 2018).

- Epstein, J. A., H. Bang, and G. J. Botvin. 2007. Which psychosocial factors moderate or directly affect substance use among inner-city adolescents? Addictive Behaviors 32(4):700-713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.011.

- Escobedo, L. G., S. E. Marcus, D. Holtzman, and G. A. Giovino. 1993. Sports participation, age at smoking initiation, and the risk of smoking among US high school students. JAMA 269(11):1391-1395. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8441214/ (accessed January 3, 2022).

- Flay, B. R. 2009. School-based smoking prevention programs with the promise of long-term effects. Tobacco Induced Diseases 5(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1617-9625-5-6.

- Garner, T., T. Kassaye, and T. Lewis. 2013. District of Columbia communities putting prevention to work: Tobacco use. Washington, DC: District of Columbia Department of Health. Available at: https://doh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/publication/attachments/CPPW%20Tobacco%20Report%20Final%20Version.pdf (accessed January 3, 2022).

- Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies (GU). 2016. The health of the African American community in the District of Columbia: Disparities and recommendations. Washington, DC: Georgetown University School of Nursing & Health Studies. Available at: https://www.abfe.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/The-Health-of-the-African-American-Community-in-the-District-of-Columbia.pdf (accessed January 3, 2022).

- Hill, K. G., J. D. Hawkins, R. F. Catalano, R. D. Abbott, and J. Guo. 2005. Family influences on the risk of daily smoking initiation. Journal of Adolescent Health 37(3):202-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.014.

- Hosler, A. S., and I. H. Michaels. 2017. Association between food distress and smoking among racially and ethnically diverse adults, Schenectady, New York, 2013–2014. Preventing Chronic Disease 14:E71. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.160548.

- Jamal, A., E. Phillips, A. S. Gentzke, D. M. Homa, S. D. Babb, B. A. King, and L. J. Neff. 2018. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67(2):53-59. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6702a1.

- Karcher, M. J. 2005. The effects of developmental mentoring and high school mentors’ attendance on their younger mentees’ self-esteem, social skills, and connectedness. Psychology in the Schools 42(1):65-77. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20025.

- Kim, H. H., and J. Chun. 2018. Analyzing multilevel factors underlying adolescent smoking behaviors: The roles of friendship network, family relations, and school environment. Journal of School Health 88(6):434-443. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12630.

- Lantz, P. M., P. D. Jacobson, K. E. Warner, J. Wasserman, H. A. Pollack, J. Berson, and A. Ahlstrom. 2000. Investing in youth tobacco control: A review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tobacco Control 9(1):47-63. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.9.1.47.

- Li, L., R. Borland, G. T. Fong, J. F. Thrasher, D. Hammond, and K. M. Cummings. 2013. Impact of point-of-sale tobacco display bans: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Health Education Research 28(5):898-910. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyt058.

- Loewenstein, G., D. A. Asch, and K. G. Volpp. 2013. Behavioral economics holds potential to deliver better results for patients, insurers, and employers. Health Affairs 32(7):1244-1250. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1163.

- Massachusetts General Hospital. n.d. CEASE Tobacco: For clinicians. Available at: https://www.massgeneral.org/ceasetobacco/resources/clinicians/ (accessed December 28, 2018).

- Mitchell, M. S., J. M. Goodman, D. A. Alter, L. K. John, P. I. Oh, M. T. Pakosh, and G. E. Faulkner. 2013. Financial incentives for exercise adherence in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 45(5):658-667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.017.

- Nápoles, A. M., and A. L. Stewart. 2018. Transcreation: An implementation science framework for community-engaged behavioral interventions to reduce health disparities. BMC Health Services Research 18(1):710. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3521-z.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2011. Principles of community engagement, second edition. Atlanta, GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf (accessed January 3, 2022).

- Powell, L. M., S. Slater, F. J. Chaloupka, and D. Harper. 2006. Availability of physical activity-related facilities and neighborhood demographic and socioeconomic characteristics: A national study. American Journal of Public Health 96(9):1676-1680. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.065573.

- Price, R. A., J. C. Blanchard, R. Harris, T. Ruder, and C. R. Gresenz. 2013. Monitoring cancer outcomes across the continuum: Data synthesis and analysis for the District of Columbia. RAND Health Quarterly 2(4):6. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR1296.html (accessed January 3, 2022).

- Romano, P. S., J. Bloom, and S. L. Syme. 1991. Smoking, social support, and hassles in an urban African-American community. American Journal of Public Health 81(11):1415-1422. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.81.11.1415.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). n.d. Project Towards No Tobacco Use. Available at: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/npa/materials/projecttowardsnotobaccouse.pdf (accessed March 22, 2019).

- Sherman, E. J., and B. A. Primack. 2009. What works to prevent adolescent smoking? A systematic review of the National Cancer Institute’s Research-Tested Intervention Programs. Journal of School Health 79(9):391-399.

- Siegel, R. L., E. J. Jacobs, C. C. Newton, D. Feskanich, N. D. Freedman, R. L. Prentice, and A. Jemal. 2015. Deaths due to cigarette smoking for 12 smoking-related cancers in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine 175(9):1574-1576. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2398.

- Soga, M., K. J. Gaston, and Y. Yamaura. 2017. Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine Reports 5:92-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.007.

- Stokols, D. 1996. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion 10(4):282-298. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282.

- Strack, R. W., C. Magill, and K. McDonagh. 2004. Engaging youth through photovoice. Health Promotion Practice 5(1):49-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839903258015.

- Sussman, S., C. W. Dent, A. W. Stacy, C. S. Hodgson, D. Burton, and B. R. Flay. 1993a. Project Towards No Tobacco Use: Implementation, process and post-test knowledge evaluation. Health Education Research 8(1):109-123. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/8.1.109.

- Sussman, S., C. W. Dent, A. W. Stacy, P. Sun, S. Craig, T. R. Simon, D. Burton, and B. R. Flay. 1993b. Project Towards No Tobacco Use: 1-year behavior outcomes. American Journal of Public Health 83(9):1245-1250. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.83.9.1245.

- Tammelin, T., S. Näyhä, A. P. Hills, and M.-R. Järvelin. 2003. Adolescent participation in sports and adult physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 24(1):22-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00575-5.

- Tang, Y. Y., R. Tang, and M. I. Posner. 2013. Brief meditation training induces smoking reduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110(34):13971-13975. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1311887110.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 2014. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress. A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24455788/ (accessed January 3, 2022).

- Villanti, A. C., A. L. Johnson, B. K. Ambrose, K. M. Cummings, C. A. Stanton, S. W. Rose, S. P. Feirman, C. Tworek, A. M. Glasser, J. L. Pearson, A. M. Cohn, K. P. Conway, R. S. Niaura, M. Bansal-Travers, and A. Hyland. 2017. Flavored tobacco product use in youth and adults: Findings from the first wave of the PATH Study (2013–2014). American Journal of Preventive Medicine 53(2):139-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.026.

- Volpp, K. G., D. A. Asch, R. Galvin, and G. Loewenstein. 2011. Redesigning employee health incentives—lessons from behavioral economics. New England Journal of Medicine 365(5):388-390. Available at: https://www.cmu.edu/dietrich/sds/docs/loewenstein/RedesigningEmployeeHealth.pdf (accessed January 3, 2022).

- Wang, T. W., A. Gentzke, S. Sharapova, K. A. Cullen, B. K. Ambrose, and A. Jamal. 2018. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67(22):629-633. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a3.

- Webb, E. 2002. Health services: Who are the best advocates for children? Archives of Disease in Childhood 87(3):175-177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/adc.87.3.175.

- Winickoff , J. P., B. Hipple, J. Drehmer, E. Nabi, N. Hall, D. J. Ossip, and J. Friebely. 2012. The Clinical Effort Against Secondhand Smoke Exposure (CEASE) intervention: A decade of lessons learned. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management 19(9):414-419. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24379645/ (accessed January 3, 2022).

- Winkleby, M. A., E. Feighery, M. Dunn, S. Kole, D. Ahn, and J. D. Killen. 2004. Effects of an advocacy intervention to reduce smoking among teenagers. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 158(3):269-275. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.3.269.

- Yosso, T. J. 2005. Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education 8(1):69-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/136133252000341006.