CDC’s 6|18 Initiative: Accelerating Evidence into Action

Introduction

The long delay between the creation of new evidence for primary prevention by public health and widespread adoption into best practice by the health care system is well documented and a source of great frustration (Haynes and Haines, 1998). The roots of this delay are complex and lie deep within the structure of the health care system. However, this problem also represents a major opportunity if root causes can be addressed and adoption of new evidence can be accelerated. The transformation of the health care system driven by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has created such an opportunity (Burwell, 2015).

For decades, the U.S. health care system has become increasingly costly without a corresponding increase in health care quality or outcomes (Burwell, 2015). In response to this long-term trend and the multiple layers of stimulus provided by the ACA to improve coverage and introduce new payment models and care models, the system is now undergoing unprecedented change at the local, state, and nation levels (Rajkumar, Press, and Conway, 2015). The expansion of insurance coverage has given millions of Americans access to the health care system (Available at http://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/111826/ACA%20health%20insurance%20coverage%20brief%2009212015.pdf.) The shift from payment rewarding volume to new payment models based on value have restructured financial incentives. The widespread adoption of Triple Aim outcomes have focused attention on the need to improve population health (Burwell, 2015; Institute for Healthcare Innovation, 2016). The public health sector— including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), public health departments, and the academic public health community—has a critical and timely opportunity to focus attention on improving population health through the broad application of prevention strategies and services to individuals and communities.

These changes create a supportive environment for reducing the delay in incorporating more evidence-based interventions into practice, but realizing the potential for change will require new skills for the public health community and collaboration with other key stakeholders, particularly health care purchasers, payers, and providers. Much of the change continues to focus on improving clinical care, with less attention being paid to other determinants of health, which, collectively, have a greater impact on health than the care received in a clinical setting (Kindig and Stoddard, 2003). Although providers often know what works for primary and secondary prevention (CDC, 2012), prevention has traditionally been less emphasized and less resourced than management of acute and chronic health conditions.

The 6|18 Initiative described in this paper represents a major effort by CDC to engage with these stakeholders and demonstrate the ability to rapidly accelerate partner (or stakeholder) implementation of 18 evidence-based interventions that target 6 high-burden conditions (www.cdc.gov/sixeighteen). The 6|18 Initiative is a key component of CDC’s third strategic direction of strengthening public health and health care collaboration in the context of the rapidly transforming health care system. The initiative is intended to explore new ways that the public health community can add value to other stakeholders and model more effective ways of collaborating with payers, providers, and communities. This requires explicitly addressing barriers to effective partnerships, such as learning the culture of other stakeholders, understanding how to articulate a convincing business case, and addressing operational barriers to broad spread.

This paper will first present a conceptual framework for the 6|18 Initiative and summarize the criteria and process for selecting the 6 conditions and 18 interventions. Next, it will describe how CDC is building deeper partnerships: one with eight state Medicaid programs through the creation of a learning collaborative, and the second with a group of private commercial payers. Finally, the paper will offer some thoughts on how to assess the success of the initiative and how to build on the relationships that are being created.

Conceptual Framework

The CDC Office of the Associate Director for Policy (OADP) has developed a conceptual framework of prevention with three categories—or buckets—each of which is needed to yield the most promising results (Auerbach, 2016). Such a focus may be particularly useful as a way of guaranteeing that insurer and provider-oriented approaches do not neglect attention to the environmental factors that have an enormous impact on health, and that public health practitioners do not neglect the contributions they can make to the provision of clinical office-based care. The three buckets are:

- Traditional clinical prevention interventions. These approaches involve the care provided most often by physicians and nurses in a doctor’s office setting in a routine one-to-one encounter. They have a strong evidence base for efficacy in health and/or cost impact. Examples include seasonal flu vaccines, colonoscopies, and screening for obesity and tobacco use.

- Innovative clinical preventive interventions. Bucket 2 approaches are still clinical in nature and patient-focused, but they allow for the opportunity to extend care from the clinical to community setting. They include interventions that have not been historically paid for by fee-for-service insurance and occur outside of a doctor’s office setting, but nonetheless have been proven to work in a relatively short time. An example is the use of a lay health worker to assess the home for asthma triggers as a way to augment control of asthma (Zotter, 2012).

- Total population or community-wide interventions. With bucket 3, the focus shifts. It includes interventions that are no longer oriented to a single patient or even to all those within a practice or covered by a given insurer. Rather, the target is an entire population or subpopulation typically identified by a geographic area such as a neighborhood, city, or county. And the interventions are not based in the doctor’s office but in such settings as the community, school, or workplace. This bucket is the one that is most unfamiliar to the clinical sector and most comfortable for the public health sector. While public health has significant experience in such total population approaches, not all of them have a strong evidence base. An example is the passage of smoke-free ordinances that allow an entire community to breathe smoke-free air (Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Tobacco Control, 2008).

A second element of the conceptual framework describes the stages in the transformation of the health care system to inform the identification of the barriers and facilitators to implementation. Halfon has created a helpful framework that defines three stages in the evolution of the health care system (Figure 1) (Halfon et al., 2014). The first transition moves from Health Care 1.0—a traditional, episodic, acute care–focused stage—to Health Care 2.0, which is more patient-centered and coordinates care for a variety of chronic illnesses across a broad range of caregivers and over the lifetime of the patient. Many local and regional health care systems throughout the United States are engaged in this transition and implementing new care models, such as patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations.

The second transition moves from the 2.0 patient-centered care to a community population-based system that addresses the full spectrum of health, including health care and the determinants of health, to reduce the prevalence of chronic disease and improve quality of life. This is Health Care 3.0, a community-integrated health care framework. One likely indicator of a mature 3.0 stage is a shift in accountability from a panel of patients who use a provider or health care system to the total population within a geographic area, only a subset of which stages 1.0 or 2.0 traditionally serve (Hester et al., 2015).

The different competencies inherent in each of these stages shape the ability of health care systems to implement each of the three preventive service buckets. The episodic focus of Health Care 1.0 matches the clinical services in bucket 1. Health Care 2.0’s more patient-centered approach supports both bucket 1 and the innovative clinical interventions of bucket 2, which follow patients outside the clinic’s walls. The community-centered population focus of bucket 3 requires the more comprehensive capabilities of Health Care 3.0. Recognizing the significance of the determinants of health within the 3.0 stage requires that the health system (1) expand the scope of interventions beyond clinical services to include a wide range of community-based interventions targeting nonmedical determinants of health; and (2) access data that can measure clinical and nonclinical delivery and outcomes for a total geographically defined population. Relatively few health care systems have reached the 3.0 stage, and most organizations are making the transition to 2.0. Since the first step in accelerating the adoption of prevention is to work with the current system, the 6|18 Initiative only includes interventions in the first and second buckets.

Selecting the Conditions and Interventions

CDC selected as a starting point 6 high-burden, preventable conditions that met the following criteria:

- They affect large numbers of people.

- They are associated with high health care costs.

- There are evidence-based interventions associated with the conditions that may improve health and reduce health care costs.

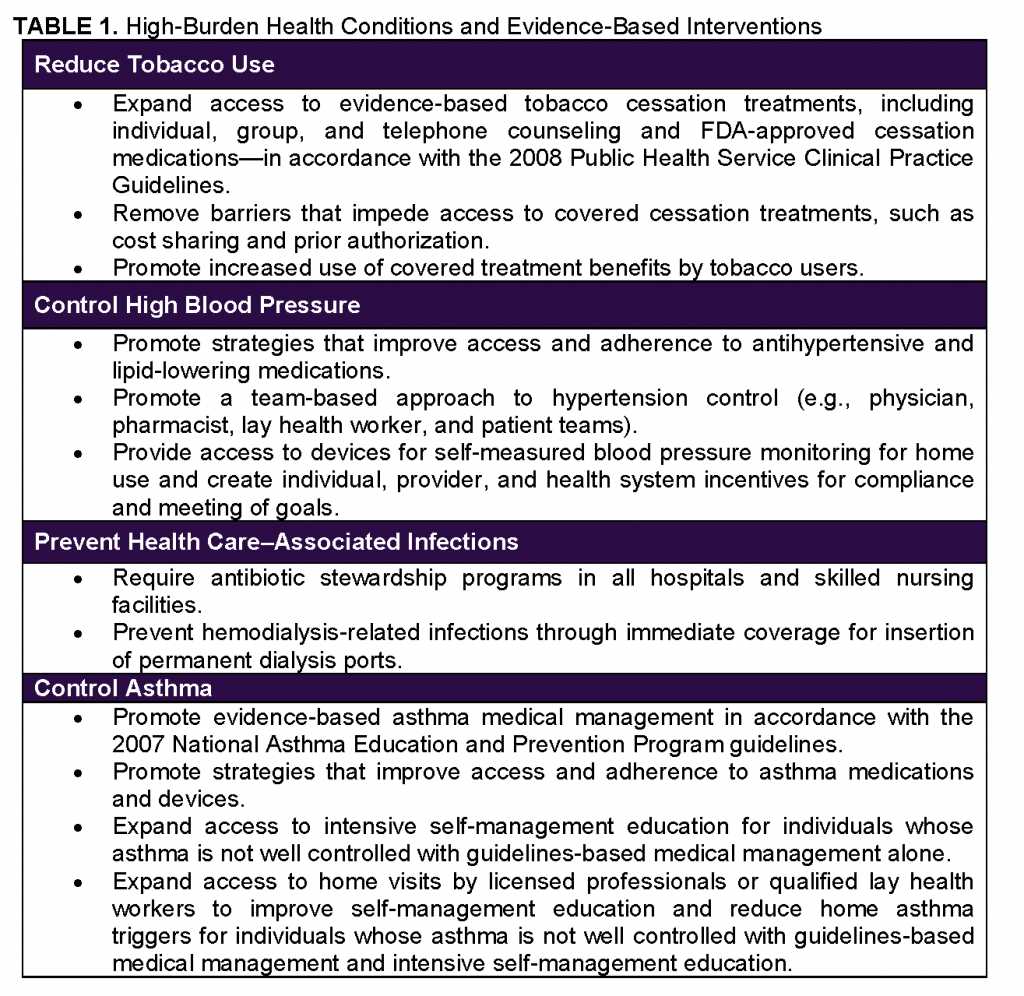

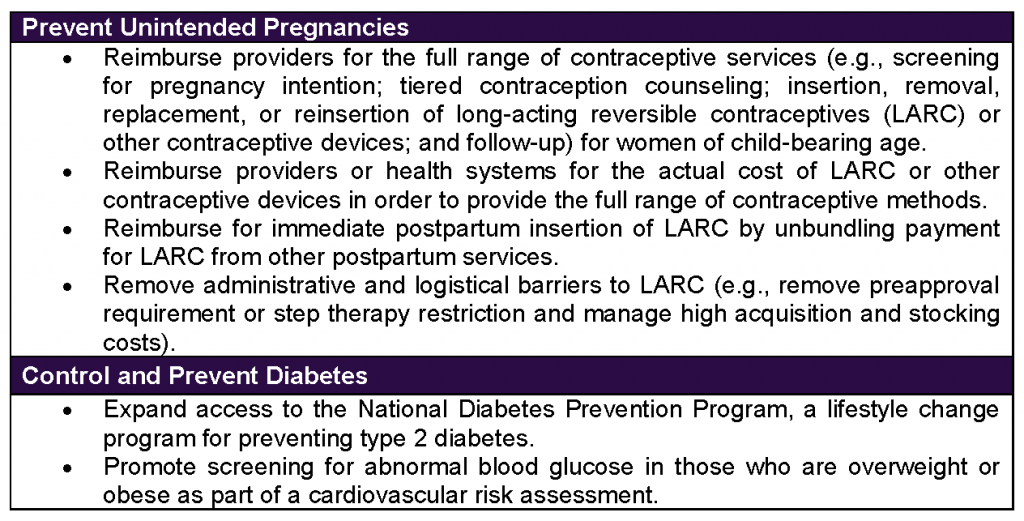

The conditions selected are: (1) tobacco use, (2) high blood pressure, (3) health care-associated infections, (4) asthma, (5) unintended pregnancies, and (6) diabetes.

CDC undertook a rigorous process to select 18 prevention and control interventions associated with the 6 conditions (Table 1) (CDC, 2016a). CDC consulted experts in insurance, health care, and health administration about interventions for improving health and controlling costs and the type of evidence payers consider when selecting new services. CDC additionally consulted two frameworks to help develop criteria for the evidence summaries assembled for each of the health conditions and associated interventions: the CDC Conceptual Framework (Spencer et al., 2013) and the Policy Analytic Framework (CDC, 2013).

The CDC Conceptual Framework informed the level of evidence for inclusion. Only studies of “moderate” or higher strength conducted in settings considered “large” were included. Five topic areas from the Conceptual Framework structured the evidence review:

- Effectiveness—How well the intervention achieved the desired outcome

- Reach—How well did the intervention reach the target group of people?

- Feasibility—How well can the intervention be put into practice?

- Sustainability—What will it take to maintain the intervention over time?

- Transferability to other settings—What other settings have used the intervention successfully?

The Policy Analytic Framework was consulted because it provides a method for decision-makers to consider policies that can improve health and includes economic considerations. In addition, some of the interventions under consideration could be used to inform policy and payment recommendations for purchasers, payers, and providers. Health care subject matter experts prioritized economic analyses as an important component in coverage and practice decisions. With this input, CDC prioritized specific domains within the Policy Analytic Framework related to public health impact, feasibility, and economic and budgetary impact.

Based on this iterative consultation with internal and external subject matter experts and the two CDC frameworks, CDC developed criteria against which to review literature for the 6|18 Initiative. Literature was selected from health and medical databases, the CDC Community Guide, the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and CDC subject matter experts. To be included in the evidence summaries, studies associated with each intervention had to meet defined levels of evidence (CDC, 2016b).

This process resulted in summaries of the interventions associated with each of the health conditions, supported by a strong and well-vetted evidence base. The interventions themselves were presented as opportunities for payers and providers to consider. Each evidence summary included the following information:

- The epidemiology or health burden of the condition

- Current coverage of the specific intervention, by payer (as of August 2015)

- Evidence-based opportunities for payers and providers

- Key take-away health and cost evidence messages for payers and providers

- Supporting health and cost evidence

This step was critical because CDC’s ability to bring credible information to purchasers, payers, and providers to inform their coverage and delivery decisions rests on its ability to demonstrate that these interventions work and can help control costs.

The following is a list of the 6 high-burden health conditions with 18 effective interventions that CDC is prioritizing to improve health and control health care costs.

Building New Partnerships: Two Coalitions

At the core of this initiative are new relationships that CDC is building with health care purchasers, payers, and providers, requiring a new understanding of the language and context within which these stakeholders are operating. To implement the 6|18 Initiative, CDC has begun to partner with a wide variety of organizations across the purchaser, payer, and provider landscape where common interests and potential for impact align best with adoption of the CDC strategies. These emerging partnerships are intended to be action-oriented, striving to increase implementation of evidence synthesized and compiled at CDC.

The Steps Toward Engagement model (Figure 2) was developed as a planning tool to structure a phased approach for CDC to engage with external partners. The goal of the process was to prepare information to help health care purchasers, payers, and providers focus their prevention coverage and efforts where they may achieve the greatest health and cost impact.

In phase 1, as a step toward developing specific purchaser, payer, and provider partnerships, CDC aligned the epidemiology of the 6 conditions with the characteristics of insured populations for whom potential partners are responsible (e.g., through employer-based insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare) in an effort to focus on areas of greatest potential impact. In phase 2, specific interventions to address the priority health conditions were identified for implementation by purchasers and payers for the target insured population. In this phase, the evidence base for the intervention was compiled with remaining gaps identified. Phase 3 built the health and cost impact case, drawing on the evidence base for the specific intervention and conducting research and analysis as needed to facilitate partner implementation of the intervention. In phase 4, CDC began actively developing purchaser and payer partnerships to highlight the evidence and health and cost impact data likely to reach the greatest health and cost returns. Throughout the process, CDC continued to gain knowledge and skills to help strengthen relationships with purchaser, payer, and provider partners in expanding prevention coverage, access, use, and quality. As interactions with partners continue to expand, CDC will learn about additional priority areas and can restart the cycle at phase 1.

CDC is expanding partnerships to include specific provider groups, additional commercial payers, and self-insured employers. Although many traditional clinical preventive interventions have historically been reimbursed by insurers, there is still room for improvement in their promotion and uptake. This could be achieved through various action steps considered by the insurers (e.g., increasing the weight with they are financially incentivized); by a clinical practice (e.g., by carefully monitoring that each of their clinicians provides them); and by public health practitioners (e.g., by designing social marketing aimed at members of the public and/or at clinical providers). In fact, coordinated multisector initiatives may result in the largest gains as illustrated in Massachusetts with its success in expanding its insurance coverage for tobacco cessation medications, linking patients to a quit line, and promoting the increased accessibility and the overall benefit of the tobacco cessation intervention in public information campaigns after the implementation of its 2006–2007 health care reform initiative (Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Tobacco Control, 2008). When all of the sectors simultaneously focused their attention on a single goal, smoking rates plummeted (Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Tobacco Control, 2008).

Partnerships

CDC is launching a 6|18 partnership with Medicaid programs to improve health and control health care costs in areas of shared priority in consultation with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, and the National Association of Medicaid Directors. This partnership will provide an exciting opportunity for select states to explore how best to translate evidence on interventions that can improve health and control costs into implementation within state Medicaid programs. Focus areas for state Medicaid program partners are likely to be related to controlling asthma, reducing tobacco use, and/or preventing unintended pregnancies, since these are high-cost, high-burden conditions within Medicaid programs. State Medicaid programs will receive targeted technical assistance and opportunities for peer-to-peer learning from CDC and its partners to support implementation efforts.

Ideally, partner Medicaid programs will have some demonstrated experience in working toward adoption of some of the evidence-based interventions in the 6|18 Initiative and will be able to work in partnership with public health. Partner Medicaid programs and their public health counterparts will engage with CDC in 6|18 implementation and/or acceleration in 2016 and beyond. A similar partnership is anticipated to be developed with commercial payers, the early stages of which are now underway.

Concluding Thoughts

What would constitute success for the 6|18 Initiative? The most direct measure is “moving the needle” in the next 12 months—accelerating the adoption of evidence into best practice by reducing initial barriers such as benefit coverage, payment policy, and provider and patient awareness and acceptance. Within 36 months, the initiative’s leaders expect reduced barriers will result in increased uptake of the 18 interventions for the initial set of Medicaid and commercial plans and the expansion of the 6|18 effort to a second, larger set of partners. Within 3 to 5 years, leaders expect to see improvements in health and cost outcomes. Forecasting these improvements in health and cost outcomes now will help keep a clear focus on those shared goals as practitioners move toward them together.

A second and equally important dimension of success is building stronger and more sustainable partnerships between public health and health care sectors based on mutual credibility and understanding. This is difficult work, but all parties have a common motivation. With approximately 17 million more people now insured, a critical opportunity exists to ensure that the prevention component of new coverage is broadly promoted and accelerated—and that new opportunities are sought to broaden coverage of prevention.4 The 6|18 Initiative can be a powerful beginning, but practitioners and stakeholders must build on that foundation and ensure that the public health and the medical and payer communities have gained an understanding of each other’s cultures, developed a greater trust in each other, and increased the respect and value for what each stakeholder brings to the table. It is the responsibility and the initiative of public health (CDC and partners) to continue to identify, emphasize, and promote these opportunities for prevention. Increasingly, CDC’s clinical partners are recognizing this as a strength of the agency and an important avenue to help the clinical system achieve its new Triple Aim (Institute for Healthcare Innovation, 2016).

The successful adoption of some 6|18 strategies is a critical first step as a proof of concept for a new way of working together. CDC and its partners need to build on the model, improving it and expanding it into new themes. Ideally, the broader public health community at the state and local level will follow CDC’s lead and explore how to create effective partnerships.

References

- Auerbach, J. 2016. The 3 buckets of prevention. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 1–4. Available at: http://journals.lww.com/jphmp/Citation/publishahead/The_3_Buckets_of_Prevention_.99695.aspx (accessed January 20, 2016).

- Burwell, S. M. 2015. Setting value-based payment goals — HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. New England Journal of Medicine 372:897-899. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1500445

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2012. Use of selected clinical preventive services among adults — United States, 2007–2010. MMWR 61 (Suppl; June 15, 2012): 1-79. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/MMWr/pdf/other/su6102.pdf (accessed July 17, 2020).

- CDC. 2013. CDC’s policy analytical framework. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- CDC. 2016a. The 6|18 Initiative: Accelerating evidence into action. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/sixeighteen (accessed January 20, 2016).

- CDC. 2016b. The 6|18 Initiative: Accelerating evidence into action – About the evidence summaries. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/sixeighteen/aboutsummaries/index.htm (accessed January 20, 2016).

- Halfon, N., P. Long, D. I. Chang, J. Hester, M. Inkelas, and A. Rodgers. 2014. Applying a 3.0 transformation framework to guide large-scale health system reform. Health Affairs 31(11). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0485

- Haynes, B., and A. Haines. 1998. Barriers and bridges to evidence-based clinical practice. British Medical Journal 317(7153):273-276. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7153.273

- Hester, J. A., P. V. Stange, L. C. Seeff, J. B. Davis, C. and A. Craft. 2015. Toward sustainable improvements in population health: Overview of community integration structures and emerging innovations in financing. CDC Health Policy Series, No. 2. Institute for Healthcare Innovation. 2016. Triple Aim Initiative. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx (accessed January 14, 2016).

- Kindig, D., and G. Stoddart. 2003. What is population health? American Journal of Public Health 93(3):380-383. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.3.380

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Tobacco Control. 2008. Massachusetts Tobacco Control Program: Reducing the health and economic burden of tobacco use [fact sheet]. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/tobacco-control/program-overview.pdf (accessed January 20, 2016).

- Rajkumar, R., M. J. Press, and P. H. Conway. 2015. The CMS Innovation Center–a five-year self-assessment. New England Journal of Medicine 372(21):1981-1983. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1501951

- Spencer, L. M., M. W. Schooley, L. A. Anderson, C. S. Kochtitzky, A. S. DeGroff, H. M. Devlin, and S. L. Mercer ‘2013. Seeking best practices: A conceptual framework for planning and improving evidence-based practices. Preventing Chronic Disease 10:130186. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.130186.

- Zotter, J. 2012. The role of community health workers in addressing modifiable asthma risk factors in Massachusetts. Available at: http://pedicair.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Zotter-CHW-inMA.pdf (accessed January 20, 2016).